2.3: Babylonia

- Page ID

- 46090

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Babylon

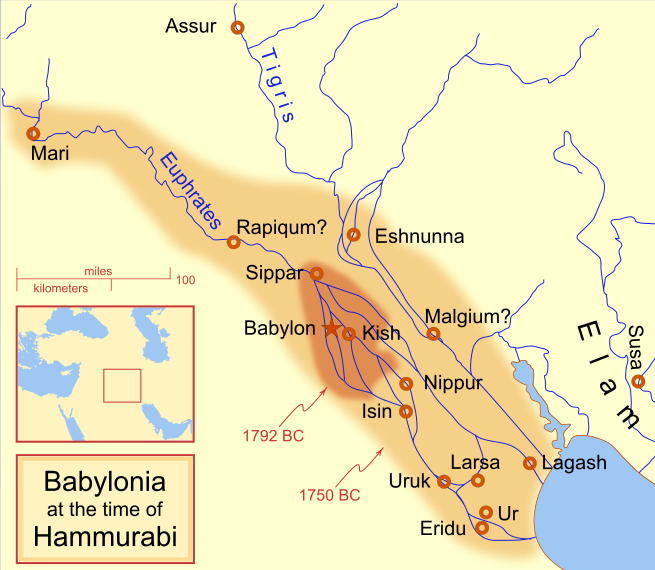

Following the collapse of the Akkadians, the Babylonian Empire flourished under Hammurabi, who conquered many surrounding peoples and empires, in addition to developing an extensive code of law and establishing Babylon as a “holy city” of southern Mesopotamia.

Learning Objectives

Describe key characteristics of the Babylonian Empire under Hammurabi

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- A series of conflicts between the Amorites and the Assyrians followed the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, out of which Babylon arose as a powerful city-state c. 1894 BCE.

- Babylon remained a minor territory for a century after it was founded, until the reign of its sixth Amorite ruler, Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE), an extremely efficient ruler who established a bureaucracy with taxation and centralized government.

- Hammurabi also enjoyed various military successes over the whole of southern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iran and Syria, and the old Assyrian Empire in Asian Minor.

- After the death of Hammurabi, the First Babylonian Dynasty eventually fell due to attacks from outside its borders.

Key Terms

- Marduk: The south Mesopotamian god that rose to supremacy in the pantheon over the previous god, Enlil.

- Hammurabi: The sixth king of Babylon, who, under his rule, saw Babylonian advancements, both militarily and bureaucratically.

- Code of Hammurabi: A code of law that echoed and improved upon earlier written laws of Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria.

- Amorites: An ancient Semitic-speaking people from ancient Syria who also occupied large parts of Mesopotamia in the 21st Century BCE.

The Rise of the First Babylonian Dynasty

Following the disintegration of the Akkadian Empire, the Sumerians rose up with the Third Dynasty of Ur in the late 22nd century BCE, and ejected the barbarian Gutians from southern Mesopotamia. The Sumerian “Ur-III” dynasty eventually collapsed at the hands of the Elamites, another Semitic people, in 2002 BCE. Conflicts between the Amorites (Western Semitic nomads) and the Assyrians continued until Sargon I (1920-1881 BCE) succeeded as king in Assyria and withdrew Assyria from the region, leaving the Amorites in control (the Amorite period).

One of these Amorite dynasties founded the city-state of Babylon circa 1894 BCE, which would ultimately take over the others and form the short-lived first Babylonian empire, also called the Old Babylonian Period.

A chieftain named Sumuabum appropriated the then relatively small city of Babylon from the neighboring Mesopotamian city state of Kazallu, turning it into a state in its own right. Sumuabum appears never to have been given the title of King, however.

The Babylonians Under Hammurabi

Babylon remained a minor territory for a century after it was founded, until the reign of its sixth Amorite ruler, Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE). He was an efficient ruler, establishing a centralized bureaucracy with taxation. Hammurabi freed Babylon from Elamite dominance, and then conquered the whole of southern Mesopotamia, bringing stability and the name of Babylonia to the region.

The armies of Babylonia under Hammurabi were well-disciplined, and he was able to invade modern-day Iran to the east and conquer the pre-Iranic Elamites, Gutians and Kassites. To the west, Hammurabi enjoyed military success against the Semitic states of the Levant (modern Syria), including the powerful kingdom of Mari. Hammurabi also entered into a protracted war with the Old Assyrian Empire for control of Mesopotamia and the Near East. Assyria had extended control over parts of Asia Minor from the 21st century BCE, and from the latter part of the 19th century BCE had asserted itself over northeast Syria and central Mesopotamia as well. After a protracted, unresolved struggle over decades with the Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan, Hammurabi forced his successor, Mut-Ashkur, to pay tribute to Babylon c. 1751 BCE, thus giving Babylonia control over Assyria’s centuries-old Hattian and Hurrian colonies in Asia Minor.

One of the most important works of this First Dynasty of Babylon was the compilation in about 1754 BCE of a code of laws, called the Code of Hammurabi, which echoed and improved upon the earlier written laws of Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria. It is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world. The Code consists of 282 laws, with scaled punishments depending on social status, adjusting “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” Nearly one-half of the Code deals with matters of contract. A third of the code addresses issues concerning household and family relationships.

From before 3000 BC until the reign of Hammurabi, the major cultural and religious center of southern Mesopotamia had been the ancient city of Nippur, where the god Enlil reigned supreme. However, with the rise of Hammurabi, this honor was transferred to Babylon, and the god Marduk rose to supremacy (with the god Ashur remaining the dominant deity in Assyria). The city of Babylon became known as a “holy city,” where any legitimate ruler of southern Mesopotamia had to be crowned. Hammurabi turned what had previously been a minor administrative town into a major city, increasing its size and population dramatically, and conducting a number of impressive architectural works.

The Decline of the First Babylonian Dynasty

Despite Hammurabi’s various military successes, southern Mesopotamia had no natural, defensible boundaries, which made it vulnerable to attack. After the death of Hammurabi, his empire began to disintegrate rapidly. Under his successor Samsu-iluna (1749-1712 BCE), the far south of Mesopotamia was lost to a native Akkadian king, called Ilum-ma-ili, and became the Sealand Dynasty; it remained free of Babylon for the next 272 years.

Both the Babylonians and their Amorite rulers were driven from Assyria to the north by an Assyrian-Akkadian governor named Puzur-Sin, c. 1740 BCE. Amorite rule survived in a much-reduced Babylon, Samshu-iluna’s successor, Abi-Eshuh, made a vain attempt to recapture the Sealand Dynasty for Babylon, but met defeat at the hands of king Damqi-ilishu II. By the end of his reign, Babylonia had shrunk to the small and relatively weak nation it had been upon its foundation.

Hammurabi’s Code

The Code of Hammurabi was a collection of 282 laws, written in c. 1754 BCE in Babylon, which focused on contracts and family relationships, featuring a presumption of innocence and the presentation of evidence.

Learning Objectives

Describe the significance of Hammurabi’s code

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Code of Hammurabi is one of the oldest deciphered writings of length in the world (written c. 1754 BCE), and features a code of law from ancient Babylon in Mesopotamia.

- The Code consisted of 282 laws, with punishments that varied based on social status (slaves, free men, and property owners).

- Some have seen the Code as an early form of constitutional government, as an early form of the presumption of innocence, and as the ability to present evidence in one’s case.

- Major laws covered in the Code include slander, trade, slavery, the duties of workers, theft, liability, and divorce. Nearly half of the code focused on contracts, and a third on household relationships.

- There were three social classes: the amelu (the elite), the mushkenu (free men) and ardu (slave).

- Women had limited rights, and were mostly based around marriage contracts and divorce rights.

- A stone stele featuring the Code was discovered in 1901, and is currently housed in the Louvre.

Key Terms

- cuneiform: Wedge-shaped characters used in the ancient writing systems of Mesopotamia, impressed on clay tablets.

- ardu: In Babylon, a slave.

- mushkenu: In Babylon, a free man who was probably landless.

- amelu: In Babylon, an elite social class of people.

- stele: A stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected as a monument.

The Code of Hammurabi is one of the oldest deciphered writings of length in the world, and features a code of law from ancient Babylon in Mesopotamia. Written in about 1754 BCE by the sixth king of Babylon, Hammurabi, the Code was written on stone stele and clay tablets. It consisted of 282 laws, with punishments that varied based on social status (slaves, free men, and property owners). It is most famous for the “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” (lex talionis) form of punishment. Other forms of codes of law had been in existence in the region around this time, including the Code of Ur-Nammu, king of Ur (c. 2050 BCE), the Laws of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BCE) and the codex of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c. 1870 BCE).

The laws were arranged in groups, so that citizens could easily read what was required of them. Some have seen the Code as an early form of constitutional government, and as an early form of the presumption of innocence, and the ability to present evidence in one’s case. Intent was often recognized and affected punishment, with neglect severely punished. Some of the provisions may have been codification of Hammurabi’s decisions, for the purpose of self-glorification. Nevertheless, the Code was studied, copied, and used as a model for legal reasoning for at least 1500 years after.

The prologue of the Code features Hammurabi stating that he wants “to make justice visible in the land, to destroy the wicked person and the evil-doer, that the strong might not injure the weak.” Major laws covered in the Code include slander, trade, slavery, the duties of workers, theft, liability, and divorce. Nearly half of the code focused on contracts, such as wages to be paid, terms of transactions, and liability in case of property damage. A third of the code focused on household and family issues, including inheritance, divorce, paternity and sexual behavior. One section establishes that a judge who incorrectly decides an issue may be removed from his position permanently. A few sections address military service.

One of the most well-known sections of the Code was law #196: “If a man destroy the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye. If one break a man’s bone, they shall break his bone. If one destroy the eye of a freeman or break the bone of a freeman he shall pay one gold mina. If one destroy the eye of a man’s slave or break a bone of a man’s slave he shall pay one-half his price.”

The Social Classes

Under Hammurabi’s reign, there were three social classes. The amelu was originally an elite person with full civil rights, whose birth, marriage and death were recorded. Although he had certain privileges, he also was liable for harsher punishment and higher fines. The king and his court, high officials, professionals and craftsmen belonged to this group. The mushkenu was a free man who may have been landless. He was required to accept monetary compensation, paid smaller fines and lived in a separate section of the city. The ardu was a slave whose master paid for his upkeep, but also took his compensation. Ardu could own property and other slaves, and could purchase his own freedom.

Women’s Rights

Women entered into marriage through a contract arranged by her family. She came with a dowry, and the gifts given by the groom to the bride also came with her. Divorce was up to the husband, but after divorce he then had to restore the dowry and provide her with an income, and any children came under the woman’s custody. However, if the woman was considered a “bad wife” she might be sent away, or made a slave in the husband’s house. If a wife brought action against her husband for cruelty and neglect, she could have a legal separation if the case was proved. Otherwise, she might be drowned as punishment. Adultery was punished with drowning of both parties, unless a husband was willing to pardon his wife.

Discovery of the Code

Archaeologists, including Egyptologist Gustave Jequier, discovered the code in 1901 at the ancient site of Susa in Khuzestan; a translation was published in 1902 by Jean-Vincent Scheil. A basalt stele containing the code in cuneiform script inscribed in the Akkadian language is currently on display in the Louvre, in Paris, France. Replicas are located at other museums throughout the world.

Babylonian Culture

Hallmarks of Babylonian culture include mudbrick architecture, extensive astronomical records and logs, diagnostic medical handbooks, and translations of Sumerian literature.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the extent and influence of Babylonian culture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Babylonian temples were massive structures of crude brick, supported by buttresses. Such uses of brick led to the early development of the pilaster and column, and of frescoes and enameled tiles.

- Certain pieces of Babylonian art featured crude three-dimensional statues, and gem-cutting was considered a high-perfection art.

- The Babylonians produced extensive compendiums of astronomical records containing catalogues of stars and constellations, as well as schemes for calculating various astronomical coordinates and phenomena.

- Medicinally, the Babylonians introduced basic medical processes, such as diagnosis and prognosis, and also catalogued a variety of illnesses with their symptoms.

- Both Babylonian men and women learned to read and write, and much of Babylonian literature is translated from ancient Sumerian texts, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Key Terms

- mudbrick: A brick mixture of loam, mud, sand, and water mixed with a binding material, such as rice husks or straw.

- etiology: Causation. In medicine, cause or origin of disease or condition.

- pilaster: An architectural element in classical architecture used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function.

- Epic of Gilgamesh: One of the most famous Babylonian works, a twelve-book saga translated from the original Sumerian.

- Enūma Anu Enlil: A series of cuneiform tablets containing centuries of Babylonian observations of celestial phenomena.

- Diagnostic Handbook: The most extensive Babylonian medical text, written by Esagil-kin-apli of Borsippa.

Art and Architecture

In Babylonia, an abundance of clay and lack of stone led to greater use of mudbrick. Babylonian temples were thus massive structures of crude brick, supported by buttresses. The use of brick led to the early development of the pilaster and column, and of frescoes and enameled tiles. The walls were brilliantly colored, and sometimes plated with zinc or gold, as well as with tiles. Painted terracotta cones for torches were also embedded in the plaster. In Babylonia, in place of the bas-relief, there was a preponderance of three-dimensional figures—the earliest examples being the Statues of Gudea—that were realistic, if also somewhat clumsy. The paucity of stone in Babylonia made every pebble a commodity and led to a high perfection in the art of gem-cutting.

Astronomy

During the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, Babylonian astronomers developed a new empirical approach to astronomy. They began studying philosophy dealing with the ideal nature of the universe and began employing an internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. This was an important contribution to astronomy and the philosophy of science, and some scholars have thus referred to this new approach as the first scientific revolution. Tablets dating back to the Old Babylonian period document the application of mathematics to variations in the length of daylight over a solar year. Centuries of Babylonian observations of celestial phenomena are recorded in a series of cuneiform tablets known as the ” Enūma Anu Enlil.” In fact, the oldest significant astronomical text known to mankind is Tablet 63 of the Enūma Anu Enlil, the Venus tablet of Ammi-saduqa, which lists the first and last visible risings of Venus over a period of about 21 years. This record is the earliest evidence that planets were recognized as periodic phenomena. The oldest rectangular astrolabe dates back to Babylonia c. 1100 BCE. The MUL.APIN contains catalogues of stars and constellations as well as schemes for predicting heliacal risings and the settings of the planets, as well as lengths of daylight measured by a water-clock, gnomon, shadows, and intercalations. The Babylonian GU text arranges stars in “strings” that lie along declination circles (thus measuring right-ascensions or time-intervals), and also employs the stars of the zenith, which are also separated by given right-ascensional differences.

Medicine

The oldest Babylonian texts on medicine date back to the First Babylonian Dynasty in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE. The most extensive Babylonian medical text, however, is the Diagnostic Handbook written by the ummânū, or chief scholar, Esagil-kin-apli of Borsippa.

The Babylonians introduced the concepts of diagnosis, prognosis, physical examination, and prescriptions. The Diagnostic Handbook additionally introduced the methods of therapy and etiology outlining the use of empiricism, logic, and rationality in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. For example, the text contains a list of medical symptoms and often detailed empirical observations along with logical rules used in combining observed symptoms on the body of a patient with its diagnosis and prognosis. In particular, Esagil-kin-apli discovered a variety of illnesses and diseases and described their symptoms in his Diagnostic Handbook, including those of many varieties of epilepsy and related ailments.

Literature

Libraries existed in most towns and temples. Women as well as men learned to read and write, and had knowledge of the extinct Sumerian language, along with a complicated and extensive syllabary.

A considerable amount of Babylonian literature was translated from Sumerian originals, and the language of religion and law long continued to be written in the old agglutinative language of Sumer. Vocabularies, grammars, and interlinear translations were compiled for the use of students, as well as commentaries on the older texts and explanations of obscure words and phrases. The characters of the syllabary were organized and named, and elaborate lists of them were drawn up.

There are many Babylonian literary works whose titles have come down to us. One of the most famous of these was the Epic of Gilgamesh, in twelve books, translated from the original Sumerian by a certain Sin-liqi-unninni, and arranged upon an astronomical principle. Each division contains the story of a single adventure in the career of King Gilgamesh. The whole story is a composite product, and it is probable that some of the stories are artificially attached to the central figure.

Philosophy

The origins of Babylonian philosophy can be traced back to early Mesopotamian wisdom literature, which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularly ethics, in the forms of dialectic, dialogs, epic poetry, folklore, hymns, lyrics, prose, and proverbs. Babylonian reasoning and rationality developed beyond empirical observation. It is possible that Babylonian philosophy had an influence on Greek philosophy, particularly Hellenistic philosophy. The Babylonian text Dialogue of Pessimism contains similarities to the agonistic thought of the sophists, the Heraclitean doctrine of contrasts, and the dialogs of Plato, as well as a precursor to the maieutic Socratic method of Socrates.

Neo-Babylonian Culture

The resurgence of Babylonian culture in the 7th and 6th century BCE resulted in a number of developments. In astronomy, a new approach was developed, based on the philosophy of the ideal nature of the early universe, and an internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. Some scholars have called this the first scientific revolution, and it was later adopted by Greek astronomers. The Babylonian astronomer Seleucus of Seleucia (b. 190 BCE) supported a heliocentric model of planetary motion. In mathematics, the Babylonians devised the base 60 numeral system, determined the square root of two correctly to seven places, and demonstrated knowledge of the Pythagorean theorem before Pythagoras.

Nebuchadnezzar and the Fall of Babylon

The Kassite Dynasty ruled Babylonia following the fall of Hammurabi and was succeeded by the Second Dynasty of Isin, during which time the Babylonians experienced military success and cultural upheavals under Nebuchadnezzar.

Learning Objectives

Describe the key characteristics of the Second Dynasty of Isin

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Following the collapse of the First Babylonian Dynasty under Hammurabi, the Babylonian Empire entered a period of relatively weakened rule under the Kassites for 576 years. The Kassite Dynasty eventually fell itself due to the loss of territory and military weakness.

- The Kassites were succeeded by the Elamites, who themselves were conquered by Marduk -kabit-ahheshu, the founder of the Second Dynasty of Isin.

- Nebuchadnezzar I was the most famous ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin. He enjoyed military successes for the first part of his career, then turned to peaceful building projects in his later years.

- The Babylonian Empire suffered major blows to its power when Nebuchadnezzar’s sons lost a series of wars with Assyria, and their successors effectively became vassals of the Assyrian king. Babylonia descended into a period of chaos in 1026 BCE.

Key Terms

- Elamites: An ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran.

- Kassite Dynasty: An ancient Near Eastern people who controlled Babylonia for nearly 600 years after the fall of the First Babylonian Dynasty.

- Nebuchadnezzar I: The most famous ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin, who sacked the Elamite capital of Susa and devoted himself to peaceful building projects after securing Babylonia’s borders.

- Assyrian Empire: A major Semitic empire of the Ancient Near East which existed as an independent state for a period of approximately nineteen centuries.

- Kudurru: A type of stone document used as boundary stones and as records of land grants to vassals by the Kassites in ancient Babylonia.

- Marduk-kabit-ahheshu: Overthrower of the Elamites and the founder of the Second Dynasty of Isin.

The Fall of the Kassite Dynasty and the Rise of the Second Dynasty of Isin

Following the collapse of the First Babylonian Dynasty under Hammurabi, the Babylonian Empire entered a period of relatively weakened rule under the Kassites for 576 years—

the longest dynasty in Babylonian history. The Kassite Dynasty eventually fell due to the loss of territory and military weakness, which resulted in the evident reduction in literacy and culture. In 1157 BCE, Babylon was conquered by Shutruk-Nahhunte of Elam.

The Elamites did not remain in control of Babylonia long, and Marduk-kabit-ahheshu (1155-1139 BCE) established the Second Dynasty of Isin. This dynasty was the very first native Akkadian-speaking south Mesopotamian dynasty to rule Babylon, and was to remain in power for some 125 years. The new king successfully drove out the Elamites and prevented any possible Kassite revival. Later in his reign, he went to war with Assyria and had some initial success before suffering defeat at the hands of the Assyrian king Ashur-Dan I. He was succeeded by his son Itti-Marduk-balatu in 1138 BCE, who was followed a year later by Ninurta-nadin-shumi in 1137 BCE.

The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I and His Sons

Nebuchadnezzar I (1124-1103 BCE) was the most famous ruler of the Second Dynasty of Isin. He not only fought and defeated the Elamites and drove them from Babylonian territory but invaded Elam itself, sacked the Elamite capital Susa, and recovered the sacred statue of Marduk that had been carried off from Babylon. In the later years of his reign, he devoted himself to peaceful building projects and securing Babylonia’s borders. His construction activities are memorialized in building inscriptions of the Ekituš-ḫegal-tila, the temple of Adad in Babylon, and on bricks from the temple of Enlil in Nippur. A late Babylonian inventory lists his donations of gold vessels in Ur. The earliest of three extant economic texts is dated to Nebuchadnezzar’s eighth year; in addition to two kudurrus and a stone memorial tablet, they form the only existing commercial records. These artifacts evidence the dynasty’s power as builders, craftsmen, and managers of the business of the empire.

Nebuchadnezzar was succeeded by his two sons, firstly Enlil-nadin-apli (1103-1100 BCE), who lost territory to Assyria, and then Marduk-nadin-ahhe (1098-1081 BCE), who also went to war with Assyria. Some initial success in these conflicts gave way to catastrophic defeat at the hands of Tiglath-pileser I, who annexed huge swathes of Babylonian territory, thereby further expanding the Assyrian Empire. Following this military defeat, a terrible famine gripped Babylon, which invited attacks from Semitic Aramean tribes from the west.

In 1072 BCE, King Marduk-shapik-zeri signed a peace treaty with Ashur-bel-kala of Assyria. His successor, Kadašman-Buriaš, however, did not maintain his predecessor’s peaceful intentions, and his actions prompted the Assyrian king to invade Babylonia and place his own man on the throne. Assyrian domination continued until c. 1050 BCE, with the two reigning Babylonian kings regarded as vassals of Assyria. Assyria descended into a period of civil war after 1050 BCE, which allowed Babylonia to once more largely free itself from the Assyrian yoke for a few decades.

However, Babylonia soon began to suffer repeated incursions from Semitic nomadic peoples migrating from the west, and large swathes of Babylonia were appropriated and occupied by these newly arrived Arameans, Chaldeans, and Suteans. Starting in 1026 and lasting till 911 BCE, Babylonia descended into a period of chaos.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mari, Syria. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mari,_Syria. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Code of Hammurabi. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Hammurabi. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylonia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylonia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylonian Law. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonian_law. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Hammurabi's Code: An Eye for an Eye. Provided by: Ancient Civilizations. Located at: http://www.ushistory.org/civ/4c.asp. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Code of Hammurabi. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Hammurabi. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylonia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 220px-Code-de-Hammurabi-1.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Code-de-Hammurabi-1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Epic of Gilgamesh. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epic_of_gilgamesh. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylonia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- pilaster. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pilaster. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- etiology. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/etiology. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylonia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 220px-Code-de-Hammurabi-1.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Code-de-Hammurabi-1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Epic of Gilgamesh. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epic_of_gilgamesh. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Babylonia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Nebuchadnezzar I. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nebuchadnezzar_I. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylonia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylonia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 220px-Code-de-Hammurabi-1.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Code-de-Hammurabi-1.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Epic of Gilgamesh. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epic_of_gilgamesh. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Nebuchadnezzar I. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nebuchadnezzar_I. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright