Introduction

- Page ID

- 124733

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master. ~Ernest Hemingway

It is the goal of this book to help students do the following:

- Apply basic concepts for effective and concise business writing.

- Compile a well written report acceptable within a business context.

- Follow a writing process designed for business students.

- Demonstrate critical thinking, reasoning, and persuasion.

- Communicate in writing using a business model.

- Apply resources for improving business writing skills.

Chapter 1 should help the reader understand why writing is important in business and in the educational process leading up to a career in business. We’ll spell out what good writing looks like, the power of using the correct words, and the importance of continuous improvement.

What, me worry?

Most college students won’t enter the workplace as CEO or general manager (GM) of a business. Indeed, it may be several decades before you take on such a broad and generalized role. Still, having the GM’s perspective of running a business allows you to be more effective regardless of where you sit in the organization’s hierarchy. Even if you never achieve the top position in a corporate structure, knowing what these managers and leaders are dealing with and the issues they face helps to remove the mystery of why they make the choices and decisions they do.

As a new college graduate, the most probable role you will play is as an analyst. The title may be different—management trainee, consultant, accountant, marketing specialist, etc.—but the task will often involve digging into a pile of raw data, making sense out of it, and then communicating what you know to somebody else.

For many, writing a report is one of the most difficult aspects of the position of analyst. This book contains one approach to reducing the stress and challenge of such a task. Consider that the process is typically done in three stages following the organization of the next chapter: 1) analyze the situation, 2) write the report (or prepare a set of slides), and 3) edit. You are strongly encouraged to take these as unique but interconnected phases of the same process. That is, as you shift from one phase to the next, the focus of your work will change, but the ultimate end-point remains the same.

What is Good Writing?

Writing is not a science; there are few similarities between crafting a masterful business report and designing a scientific experiment. In this regard, writing is more of an art. But just like art has its “rule of thirds” (a principle that helps artists choose the placement of objects within a composition to maximize aesthetics), writing has similar guidelines to help writers make the most of their efforts. To go one step further, colleges are required to teach students how to write-in-their-profession. With this in mind, the following concepts will not only help you to write effectively in the profession of business, they will help you to demonstrate mastery as a business student. At one level, everything that follows in this book will provide deeper and finer detail on these three concepts.

Be Concise

One of the hardest things about writing in business is being concise. Doing so, however, will mark you as a savvy business professional. This means while you always want to answer the question fully, you omit everything that is unnecessary, regardless of how interesting it is. It may feel difficult to spend minutes or hours crafting a clever, insightful, and technically accurate passage only to delete it from your report, but your report will be better for it. Before you consider yourself done with a report, step away for a brief period, reread the report and consider whether the document clearly and succinctly answers the question you were asked.

Be Complete

Managers know about the power of a well-written executive summary. We put them at the beginning of the report but write them last. An executive summary needs to be accurate and concise; it should capture the totality of the report in one or a few paragraphs no matter the length of the report. In other words, the executive summary of a 100-page white paper and a 10-page summary analysis will still provide the same style—and possibly same length—of high level overview based on the contents of the report.

This doesn’t mean executives don’t want details. It means they want the story wrapped up tightly so they can prioritize the report’s content before they dig into it. Get to the point quickly, layout your analytical framework, and then explore the details of your analysis. If you have lots of data, graphs, tables, and charts, include them as clearly labeled figures and reference them in your report. For more information on how to handle large volumes of related, or possibly tangential material, see the section on Appendices.

To be complete in a business school context, include references to specific models from your course, show your calculations (complete with units of measure), and cite your sources. Equally important as having the data, is to identify and report your assumptions. Sometimes, you simply don’t have all the data you need so you have to make assumptions to complete your analysis. Clearly reporting your assumptions will allow your manager, client, or instructor to know how you got from a set of data or ideas to a specific conclusion.

Use Essential Vocabulary

Regardless of the field, the vocabulary someone uses quickly distinguishes a novice from an expert. Every profession—medicine, law, sports, music, and business—has its own unique set of specialized lexicon; your ability to use the right terms and concepts appropriately sets you apart from everyone else.

If you know the thrill of holing out from the rough on a blind approach to put you three up with two to go, or if you know the pain of receiving a cross in the box, beating the keeper, and clanging a header off the bar, you may have spent too much time on a golf links or soccer pitch, respectively. Similarly, if you claim the board destroyed shareholder value by wasting corporate resources and poisoning shareholder relationships, you will capture the attention of a hiring manager; and you had better be prepared to back it up with hard data!

In business, you don’t get much leeway when you use a business term incorrectly and you’ll be instantly branded an outsider or greenhorn. In school, you have a distinct advantage in that most instructors will provide the essential vocabulary you should master during the course. To demonstrate mastery of the topic, use that terminology when writing reports and responding to assignment prompts. School is your opportunity to try out this terminology in a learning environment, where mistakes can easily be corrected and have no long-term implications.

The Power of Words

British author, Edward George Bulwer-Lytton, is credited with the expression “the pen is mightier than the sword”. Indeed, words have the power to shape how we see the world and understanding this point is critical in writing and in life. In creating this textbook, we gained insight into the unique vocabulary we had developed as instructors. These words essentially shape the way we see the profession of teaching and using writing in teaching, so we want to call them out before going further.

Earn vs. Award. It is our belief that assignment and course grades, especially when evaluated using rubrics, are “earned” not “awarded”. This may seem to some students like “splitting hairs”, but in both course and assignment design this orientation toward “earning” focuses the locus of control squarely on the student.

Report vs. Paper/Essay. Although these terms may show up as synonyms in this textbook, we have a bias for “report”. Mostly, this is because of its use outside of academia. True, all are interchangeable, but business people are more likely to speak about reports than papers (except in the context of a “white paper”). Most certainly as a professional in the work world you are very unlikely to be assigned to write an essay.

Score vs. Grade. We use the terms “grade” and “score” interchangeably in the textbook as it relates to assignments. At times, you will see a slight bias toward using “score” in reference to assessing an assignment and “grade” in reference to a course. This bias derives from the pragmatic reality that the grade is the end result of a term’s worth of work, therefore, scores are what builds up to that end result.

Assignment vs. Prompt. These two terms are used interchangeably throughout the book. As with most languages, some subtle conventions may call for one over the other, but those distinctions are not intended to be relevant in this project. When you encounter either of these terms—or these terms used in combination with “description” and “assigned”—you can consider them to refer to the work the instructor wants from the student.

He, She, or They. There is a growing awareness in global business and education communities around gender (and other) diversity. While there is some change afoot, it is not yet official within the APA and related circles. In this textbook we have chosen to use the pronoun “they” and “their” in place of “he” or “she” or the awkward “he and she”, “he/she”, “s/he” except where it makes sense grammatically. Our decision is a style choice only and should not be interpreted as a writing rule, at least not yet. An astute student may consider asking their instructor before repeating this practice in case they have a preference.

There’s a story, which is often told in foundational business courses, about why in the 1980s Toyota was able to produce some of the most reliable cars in the world and why American companies, like General Motors, were unable to achieve the reliability and reputation that Toyota had gained. Toyota’s story is one of kaizen, which translates to continuous improvement. It’s something that was built into the company culture, the idea of always striving to get better. In a Toyota factory, if a worker on the assembly line saw a problem—a part in the wrong place, or missing—they would stop the line and fix it. Meanwhile, in GM factories, problems were ignored and dealt with later, so the factory could produce as many cars as possible in a given day. Toyota was successful because continuous improvement was built into the company culture, whereas at GM it was not. Continuous improvement is about not letting things “slide” because of laziness, indifference, or being hurried. It is about fixing mistakes and making improvements in the moment. In writing, having the mindset of continuous improvement makes us better writers.

Becoming a strong writer is a skill that takes a lifetime to develop and refine. It is a journey you started in elementary school and will continue to hone as you progress along your career path. But, continued progress is not a guarantee. It takes effort and awareness to continuously improve. As a student of business, if your aspiration is to rise in a professional or managerial hierarchy, you must be a good writer. The overriding goal of this writing guide is to help you along your journey as a writer.

Our Motivation for this Book

In light of the cost of textbooks and education in general, we undertook this project to create a free resource to be used broadly by students in a business context. We wanted to provide comprehensive coverage of the writing process, but keep our topics relevant to business education. We hope that this textbook provides equal value to both non- and native-English learners alike. Just like we acknowledge that students will continue to develop their writing skills, we expect this project to challenge and further our own skills as writers. We see this as a mutual journey and invite your comment for ways to improve the content.

~John and Julie

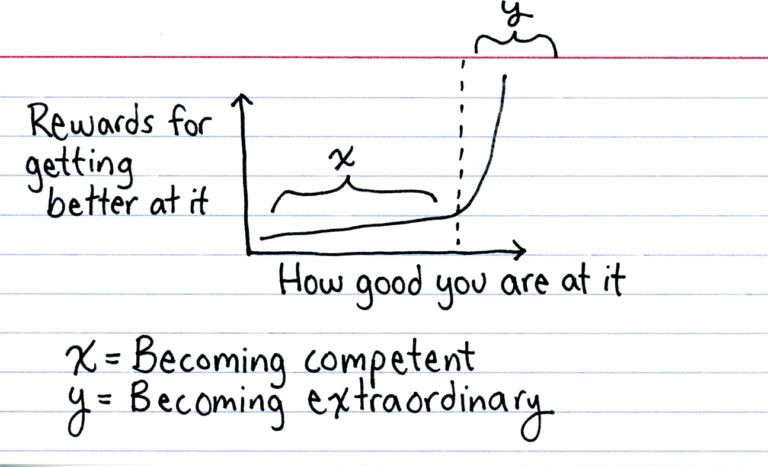

Figure 1.1 – Practice Makes Legacy. Used with Permission from Indexed© Jessica Hagy, granted 7/25/2018

Figure 1.1 – Practice Makes Legacy. Used with Permission from Indexed© Jessica Hagy, granted 7/25/2018