Structures for worship, as we have noted, were sometimes combined with or were near those created for other communal needs. We saw this with the ziggurat, in the Roman forums, and in palaces, among others. But we also have a considerable history of architecture intended solely for religious purposes. From early times, there were two distinctive conceptions for a sacred building: whether it was a house for the deity or a house for the worshippers. Beyond that, it might be for individual devotional activities or for accommodating a congregational group. We can keep these points in mind when examining the types of building designed for these goals.

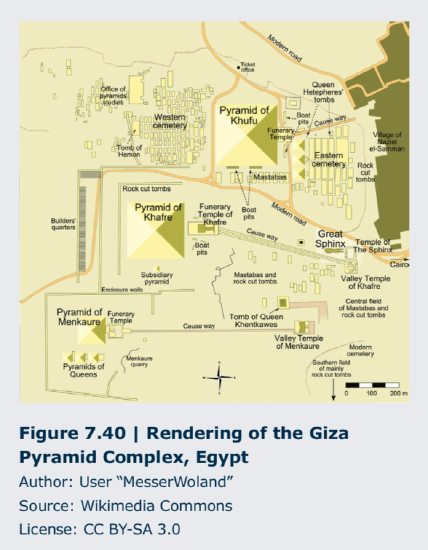

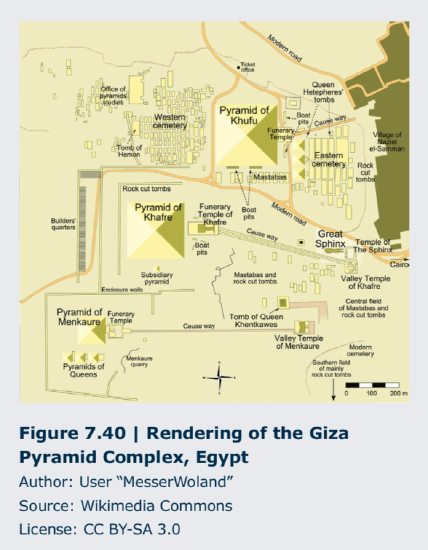

Among the earliest examples are the pyramid complexes from ancient Egypt. (Figure 7.40) The pyramids were tombs composed of millions of large stones in mathematically regular geometric structures carefully oriented to the stars. Pyramids evolved over thousands of years out of pre-Egyptian burial practices that began with placing heavy stones over gravesites to protect the occupants and their grave goods buried within.

Among the earliest examples are the pyramid complexes from ancient Egypt. (Figure 7.40) The pyramids were tombs composed of millions of large stones in mathematically regular geometric structures carefully oriented to the stars. Pyramids evolved over thousands of years out of pre-Egyptian burial practices that began with placing heavy stones over gravesites to protect the occupants and their grave goods buried within.

The Egyptians created these elaborate and massive groupings of buildings for the royal dead on the west bank of the Nile River, creating a necropolis, or city of the dead. At Giza, the body of the pharaoh or other royal family member was brought down the river from the palace to the valley temple on the edge of the pyramid precinct. After priests mummified the body of the deceased and prepared it for entombment, the body would be taken to a mortuary temple near the pyramid. (Figure 7.41) That temple was the site where ceremonies were carried out at the time of the mummy’s placement within the pyramid, as were the perpetual rituals required to honor the king in the afterlife.

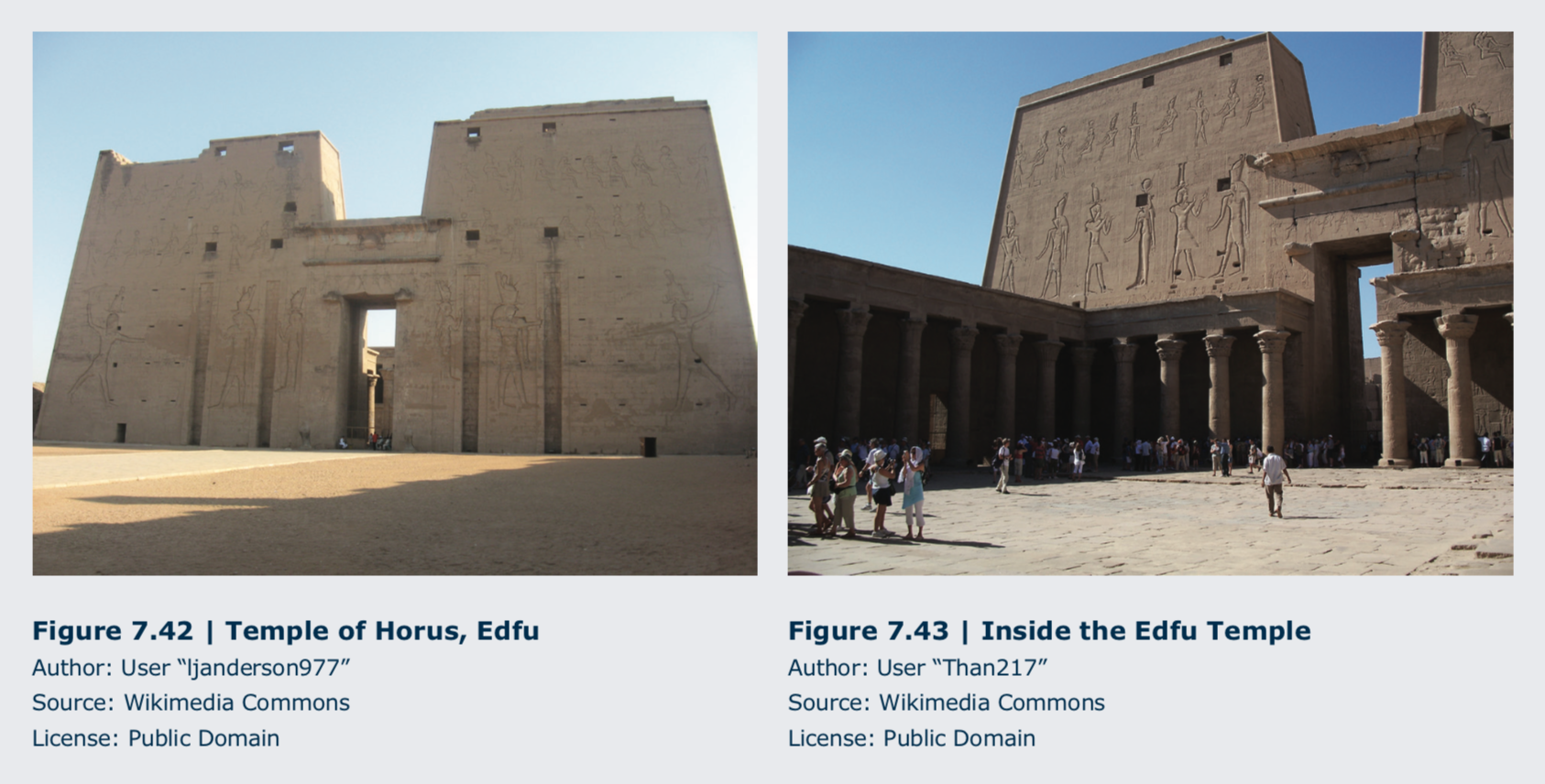

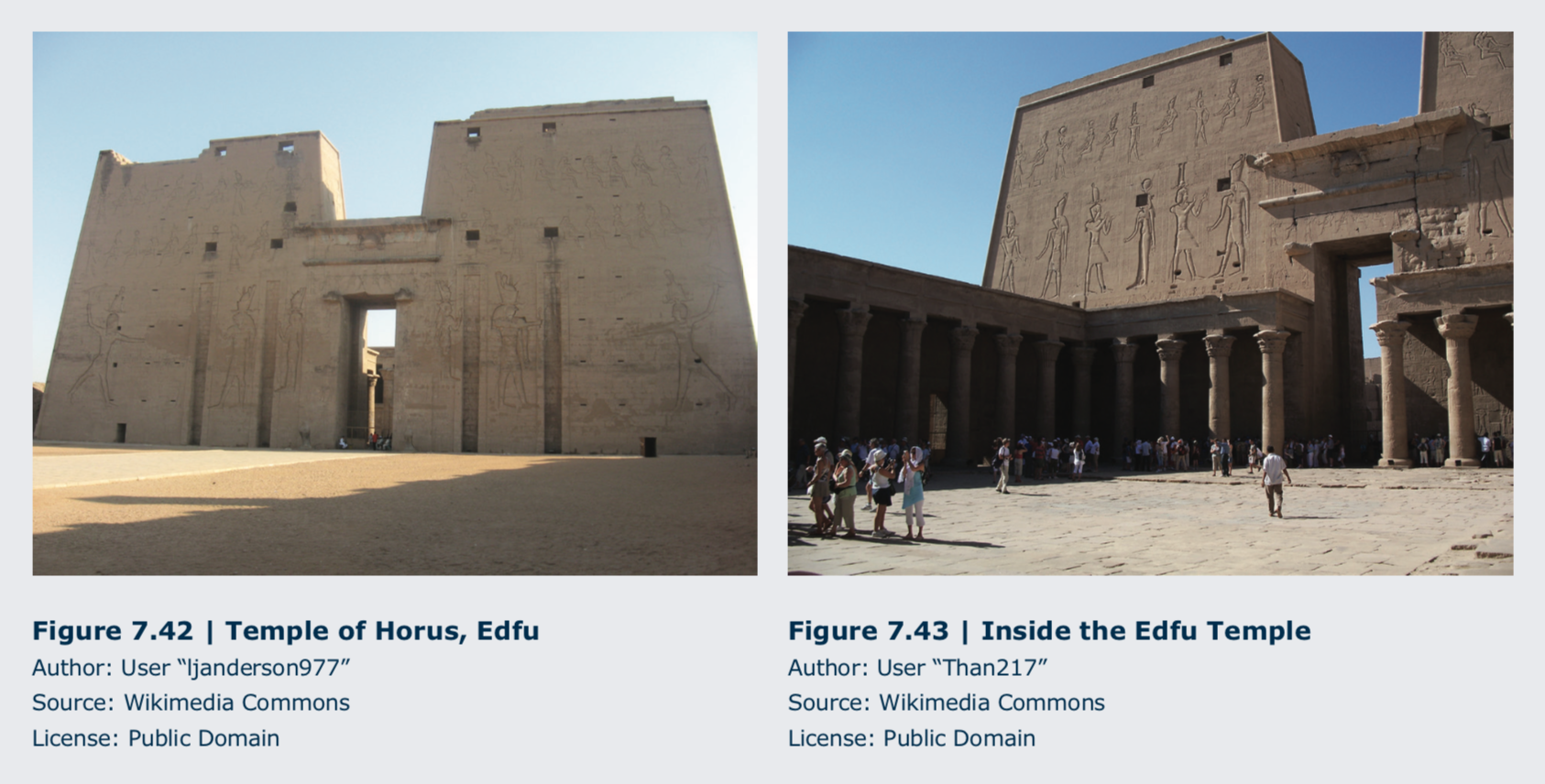

There were also temples for the living that the king would have had commissioned and served. One example is the Temple of Horus at Edfu, which has a number of typical features, although it was built relatively late in Egyptian history. It is of the pylon type, so named for the two upright structures that form its monumental façade and flank the main ceremonial portal. (Figure 7.42) The approach to temples was often along an avenue of sphinxes, imaginative hybrid creatures, part human, part animal, that led to the main door. Beyond the pylon wall was an open courtyard (Figure 7.43) and then a hypostyle hall, a structure with multiple rows of columns that support a flat roof, leading to the sanctuary. Typical of many sacred structures is this sort of staged progression by which one moves from the public or profane spaces through gradually more sacred, and often more restricted, areas that lead ultimately to the most sacred and reserved part. It is often the case that only priests or otherwise consecrated and dedicated persons are allowed in the sanctuary, the innermost and holiest space, while most of the congregation or worshipers are confined to less sacred parts of the temple, and the general public may be denied access to the premises altogether.

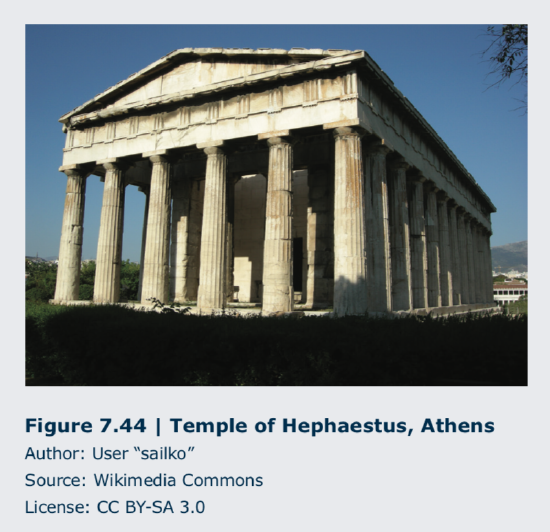

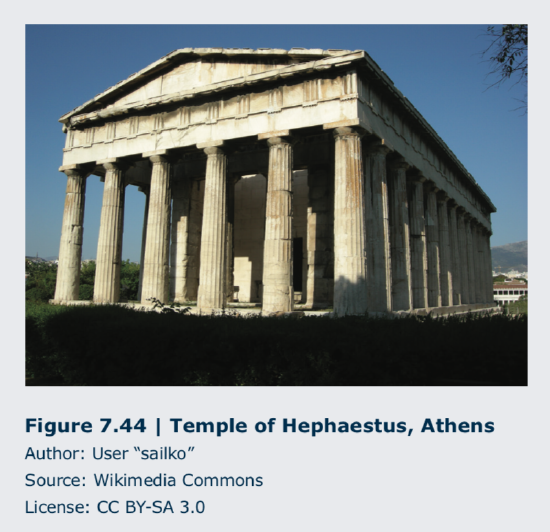

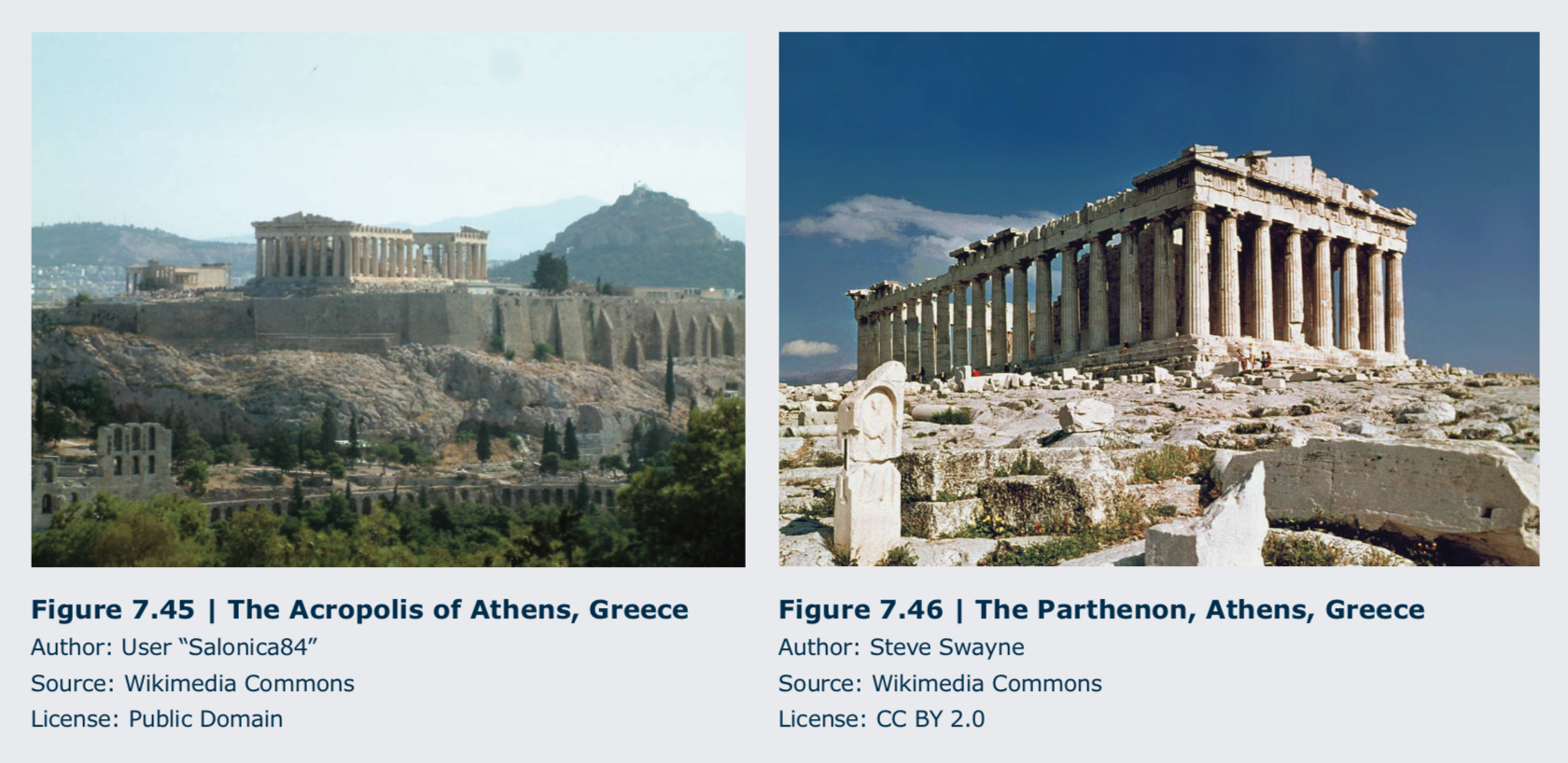

Greek temples like that devoted to Hephaestus in Athens, Greece, were not congregational at all. (Figure 7.44) They were designed as houses for the deity with a cella, or room, inside that was provided for the cult statue. Sometimes, there was also a cult treasury room within the temple, but ceremonies and sacrifices were conducted outside in the temple courtyard. Like the ziggurats, Greek temples incorporated the belief that the gods were on high, in the celestial realms, so they were often located in an acropolis, or sacred city high on a hill.

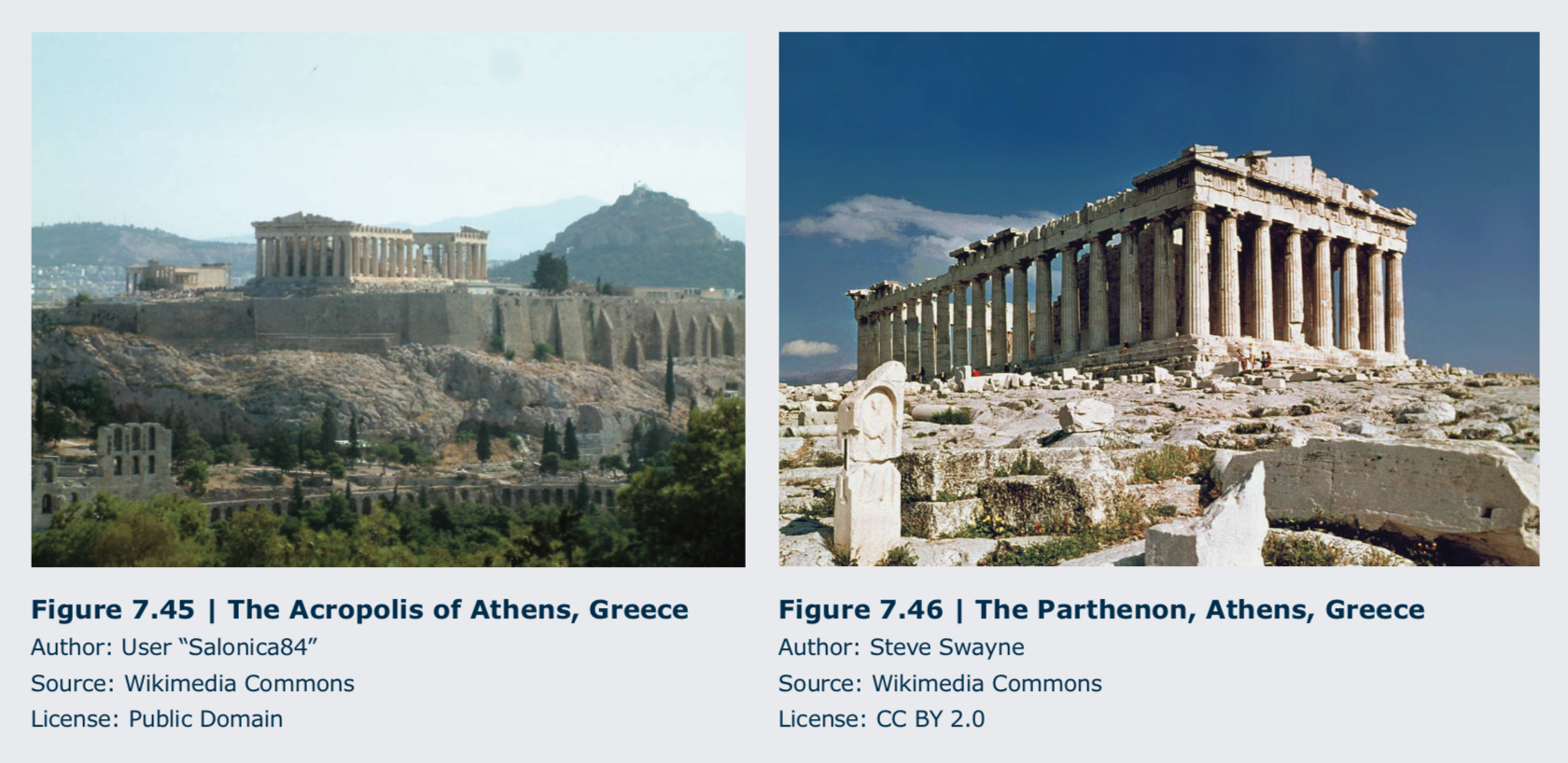

This can clearly be seen in the case of the Parthenon, dedicated to the goddess Athena, the patron of the city of Athens. (Figures 7.45 and 7.46) As in all Greek temples, a mathematical relation can be found ordering the size and relation of the Parthenon’s elements. The length to width of the structure, the height to the width, the diameter of the columns, and their spacing all conform to the golden ratio of 4 to 9. This use of a single relation between the various elements of the structure gives it an aesthetically pleasing, unified, and more solid appearance, as does the use of several optical corrections. The columns lean slightly inward, and the stylobate, the base upon which the columns stand, bows upward slightly in the middle, both to give the appearance of being completely straight and flat.

Roman temples were often built in emulation of those of the Greeks, but they made many practical changes to the designs and often placed them in the center of the community, as opposed to the separated locations preferred by the Greeks. An important and very innovative temple design was created during the early Imperial era to honor the pantheon of nine planetary deities. To address the honor of the group, rather than individual gods, this temple, the Pantheon, took a different form. (Figure 7.47)

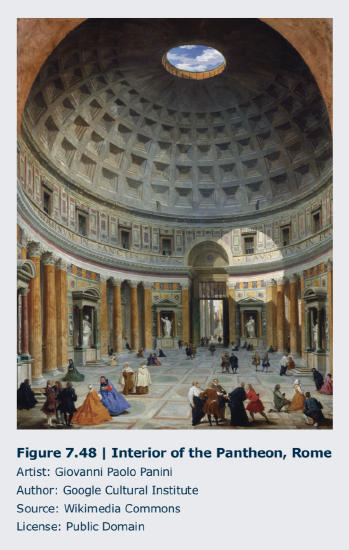

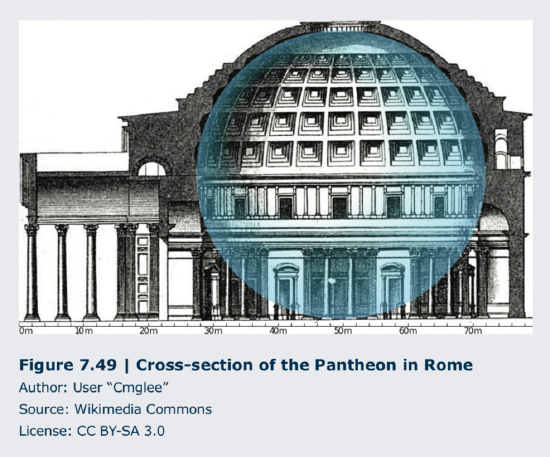

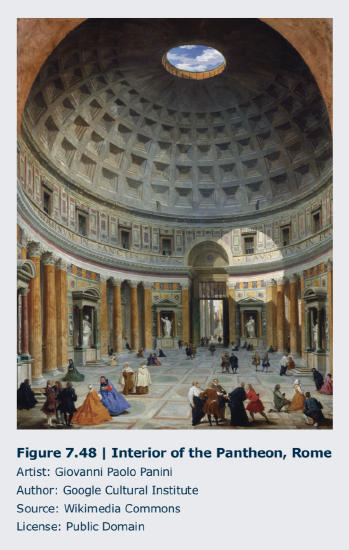

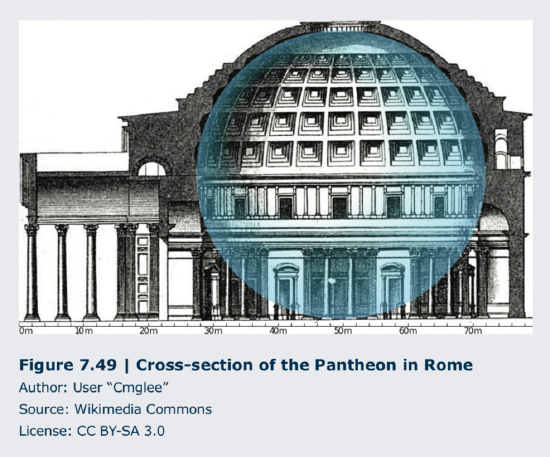

The building had a traditional temple front made up of columns supporting a triangular pediment. Rather than continuing into a rectangular, gable- roofed structure, however, the interior was an open circle with cult statues arrayed around its perimeter, each in a separate niche, or shallow recess in the wall. (Figure 7.48) That circular interior, acting as a drum, supported a huge domed space with an oculus, a circular opening, at its summit. Combining the circles of drum and dome creates a perfect sphere (diameter = height). (Figure 7.49) The whole of the structure was constructed using the ingenious Roman concrete, which allowed the creation of an unsupported dome greatly facilitated by the use of coffers, or recessed squares, which tremendously reduced the dome’s weight. The circle and square are not only featured in the ceiling construction, the repetition of those shapes is carried out in all of the architectural and decorative elements of the Pantheon’s interior and exterior.

The building had a traditional temple front made up of columns supporting a triangular pediment. Rather than continuing into a rectangular, gable- roofed structure, however, the interior was an open circle with cult statues arrayed around its perimeter, each in a separate niche, or shallow recess in the wall. (Figure 7.48) That circular interior, acting as a drum, supported a huge domed space with an oculus, a circular opening, at its summit. Combining the circles of drum and dome creates a perfect sphere (diameter = height). (Figure 7.49) The whole of the structure was constructed using the ingenious Roman concrete, which allowed the creation of an unsupported dome greatly facilitated by the use of coffers, or recessed squares, which tremendously reduced the dome’s weight. The circle and square are not only featured in the ceiling construction, the repetition of those shapes is carried out in all of the architectural and decorative elements of the Pantheon’s interior and exterior.

In addition to these singular features, the Pantheon was the first temple structure the congregation was allowed to enter. Once Christianity supplanted the ancient Roman religions, spaces with large, open interiors would be needed to house the faithful attending mass. The Pantheon served the needs of

a Christian church well, and it was converted in 609 CE. Its adaptation as a Christian church prevents our viewing it as it was intended to be used, but the Pantheon still stands in well-preserved condition and with little alteration to the structure and basic décor of fine marbles for the floor and interior columns, due to its continuous service as a house of worship since it was built in the second century CE.

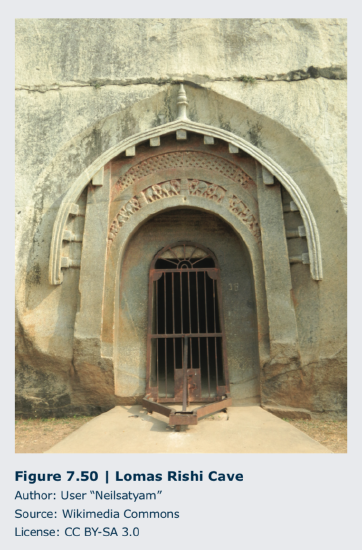

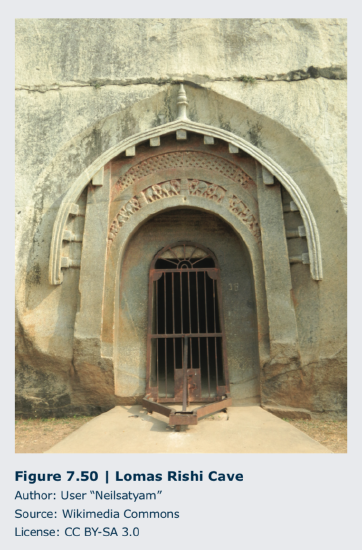

Some of the earliest evidence of worship in India shows that it was conducted in caves; we also see attempts to create worship spaces by excavating the living rock and creating larger caves for this purpose. While rock-cut architecture exists in many places around the world, its extent in India over the centuries is unsurpassed and, due to its great durability, many fine examples of it are preserved.

A very early example is the Lomas Rishi Cave in the Barabar Hills from the third century BCE. (Figure 7.50) Because it is unfinished, we have a good idea of the methods and plans for the excavation, which included the addition of a large rectangular chamber leading into a smaller circular one. The sculptural treatment of the frame of the portal is a good example of the ways in which early architecture and decoration in stone imitated prior work in impermanent materials such as wood, as was the case for early architectural design around the world. Here, the designs simulate lattice, beams, and bentwood construction.

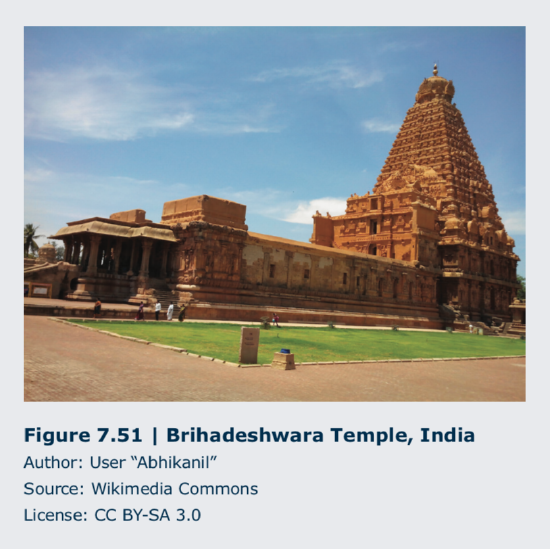

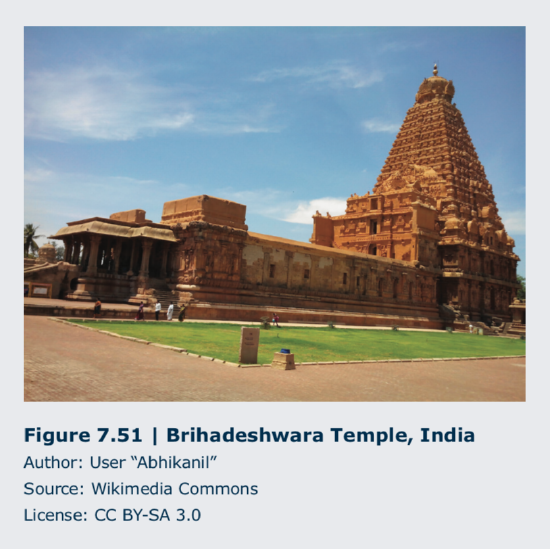

Later Indian worship structures such as the Brihadeshwara Temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, from the eleventh-century Chola Dynasty era, show the great complexity of conception of this type of worship space. (Figure 7.51) The tower at the far end is over the garba griha, or sanctuary, and as with the Temple of Horus at Edfu, there is staged progression from the profane (everyday) space to the most sacred. The whole is raised on a platform, a feature also seen in many sacred structures. Here, one must begin the approach by entering a gated courtyard, then ascend the stairs, and pass through the mandapa, or audience hall, before approaching the sanctuary. Outside the main temple but within the courtyard are subsidiary temples and shrines, as the worship is polytheistic, that is, with a great number of diverse deities.

Later Indian worship structures such as the Brihadeshwara Temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, from the eleventh-century Chola Dynasty era, show the great complexity of conception of this type of worship space. (Figure 7.51) The tower at the far end is over the garba griha, or sanctuary, and as with the Temple of Horus at Edfu, there is staged progression from the profane (everyday) space to the most sacred. The whole is raised on a platform, a feature also seen in many sacred structures. Here, one must begin the approach by entering a gated courtyard, then ascend the stairs, and pass through the mandapa, or audience hall, before approaching the sanctuary. Outside the main temple but within the courtyard are subsidiary temples and shrines, as the worship is polytheistic, that is, with a great number of diverse deities.

As is the case with most Hindu and Buddhist temples, although there are certainly ceremonial and ritual functions that are priestly duties, there is no restriction for lay people entering the sanctuary as the relationship to the deity is generally considered to be a personal one, not mediated by a priesthood.

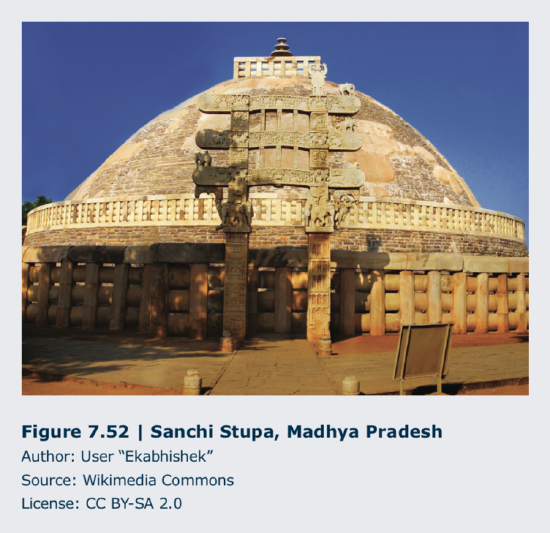

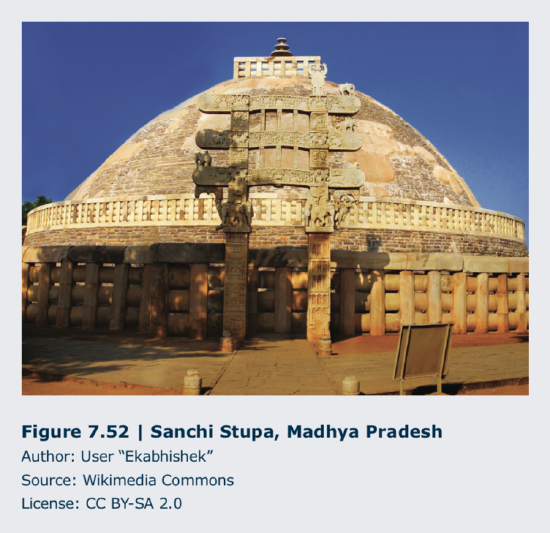

The coexistence of Hindu and Buddhist deities evidenced by their shrines appears at many sites, though usually one or the other predominates at a given site. In addition to temples, another basic structure associated with Buddhism is the stupa. (Figure 7.52) One of the oldest stupas is in India where Buddhism first arose, at Sanchi in Madya Pradesh. Established in the third century BCE, it was conceived as a burial mound of a type, as it was believed to contain part of the earthly remains of Sakyamuni, founder of Buddhism. Surrounded by a tall stone fence, it is designed for the devotee to enter the fenced area and circumambulate, or walk around, the stone-faced, rubble-filled mound.

A great deal of symbolism is associated with the form including a yasti, or mast, rising from the center of the dome that stands for an axis mundi, or axis of the world, separating the earth from the sky above. The fence and gateways are also covered with mythological carvings related to Buddhist and Hindu beliefs. (see Figure 4.23) When the Buddhist stupa form migrated to China, Japan, and elsewhere, the design evolved to include native architectural traditions resulting in the stupa form becoming the multi-tiered pagoda, a Hindu or Buddhist sacred building.

A great deal of symbolism is associated with the form including a yasti, or mast, rising from the center of the dome that stands for an axis mundi, or axis of the world, separating the earth from the sky above. The fence and gateways are also covered with mythological carvings related to Buddhist and Hindu beliefs. (see Figure 4.23) When the Buddhist stupa form migrated to China, Japan, and elsewhere, the design evolved to include native architectural traditions resulting in the stupa form becoming the multi-tiered pagoda, a Hindu or Buddhist sacred building.

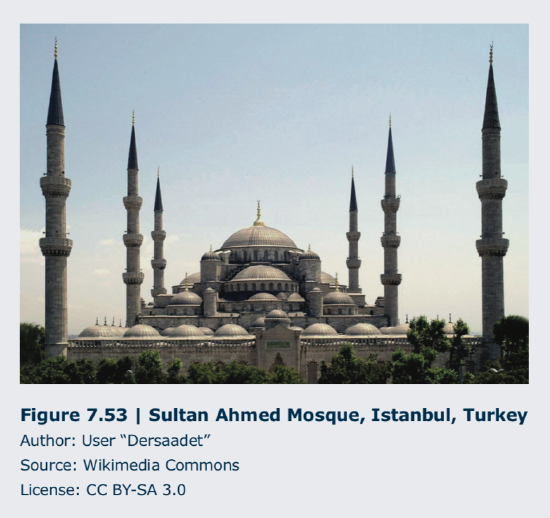

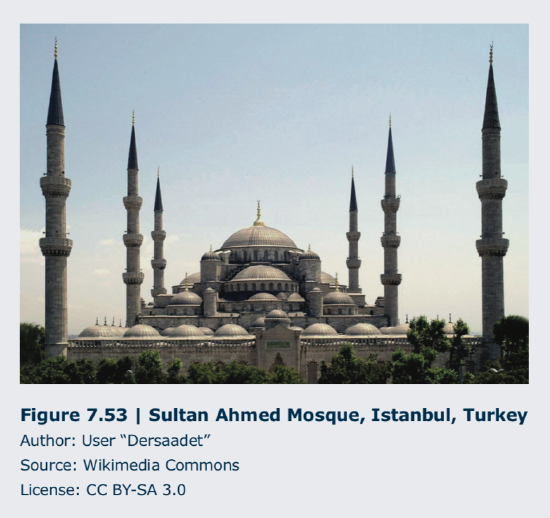

Centers for Islamic worship are housed in architectural structures known as mosques. While churches and temples associated with other faiths are generally oriented to the four cardinal directions, usually with the altar toward the east where the sun rises, the mosque will always be situated so that the worshippers face in the direction of the qibla, a fixed wall aligned to face Mecca, the city that is the epicenter for Islam. This orientation remains consistent regardless of where in the world the building is set. While several different standard architectural forms exist for a mosque, its most common distinguishing exterior feature is the minaret, the slender tower from which the call to prayer is issued. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque shows six minarets while four are common at other sites. (Figure 7.53)

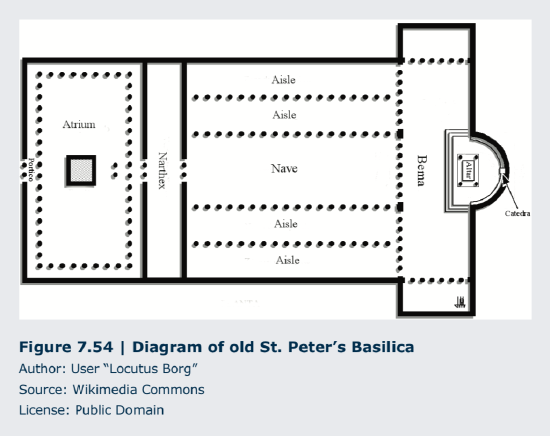

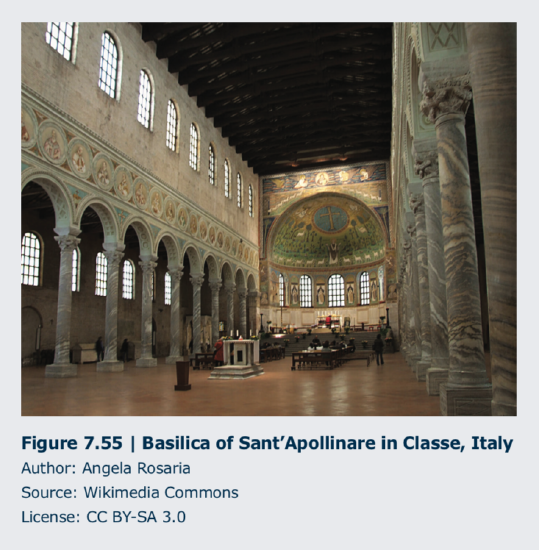

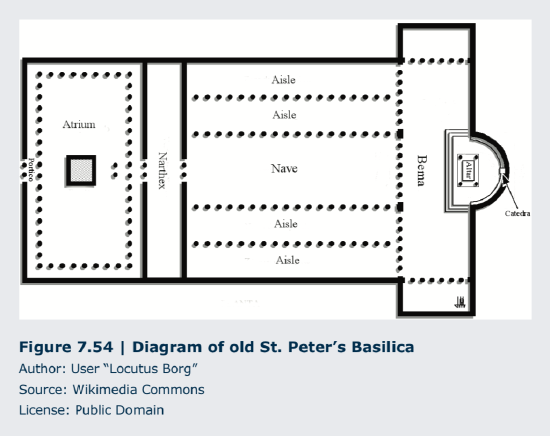

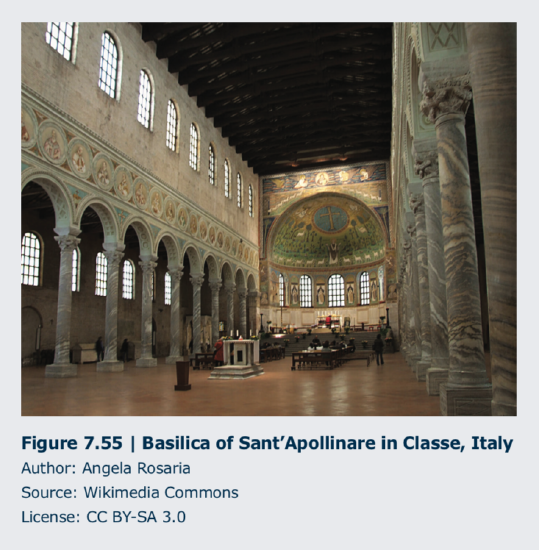

The most basic architectural form for Christian congregational churches is the basilica, a structure of longitudinal plan adapted from the Roman public building form. (Figure 7.54) The Roman basilica had an entrance on one long side that led to the large open interior space, the nave. The Christian basilica, unlike that used by the Romans, has an entrance on one end, is divided into a center nave and side aisles along its length, and holds a semi-circular apse, or recess, containing the altar at the opposite end of the longitudinal building from the entrance. (Figure 7.55)

As in other centers for worship we have seen, the holiest part of the church is farthest away from the most profane or public spaces. The progression from one end of the church to the other is a pro- cessional ritual, enhanced by the long rows of columns flanking the nave, the long exterior walls, that were often heavy wood or masonry structures until the Gothic era, and the filtered light that played among the structural components.

As in other centers for worship we have seen, the holiest part of the church is farthest away from the most profane or public spaces. The progression from one end of the church to the other is a pro- cessional ritual, enhanced by the long rows of columns flanking the nave, the long exterior walls, that were often heavy wood or masonry structures until the Gothic era, and the filtered light that played among the structural components.

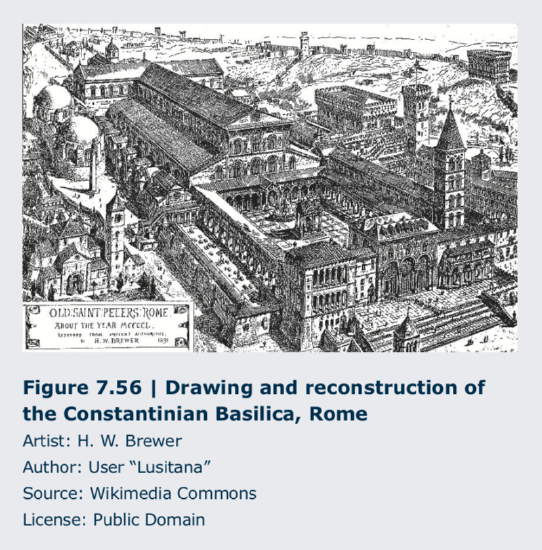

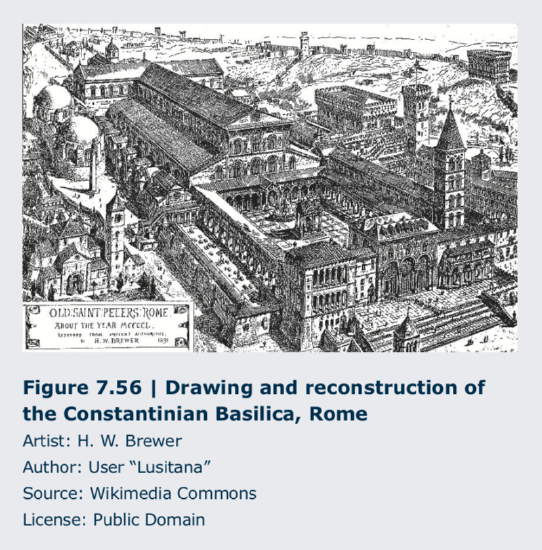

This was the case in Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, (Figure 7.56) built in the fourth century CE on the model of the Roman ba- silica type. Also based on the Roman secular model was an atrium that was placed before the entrance. The original St. Peter’s was the center of the Christian world for centuries and a model for church architecture, but it was replaced during the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods with the much grander structure that exists today in Rome.

This was the case in Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, (Figure 7.56) built in the fourth century CE on the model of the Roman ba- silica type. Also based on the Roman secular model was an atrium that was placed before the entrance. The original St. Peter’s was the center of the Christian world for centuries and a model for church architecture, but it was replaced during the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods with the much grander structure that exists today in Rome.

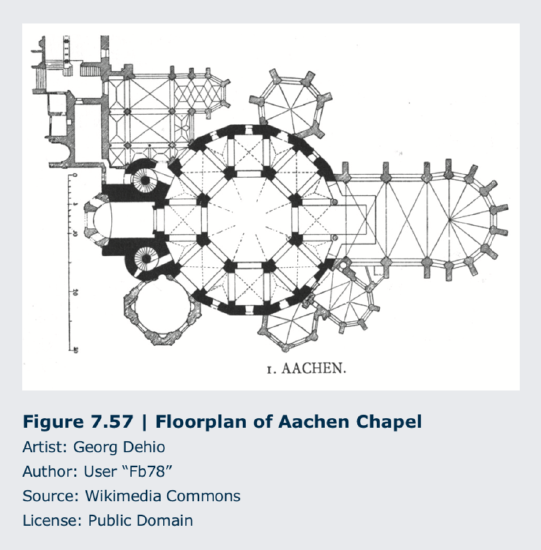

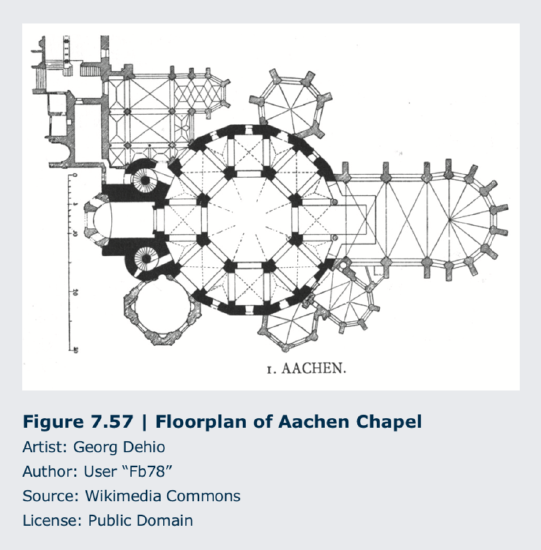

Christians in the Western Roman Empire used the basilica, or Latin cross, plan, but those in the Eastern Roman Empire, more commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, also employed the central plan, which had its origins in the circular plan, such as that used for the Pantheon. In the West, however, the circular, or central plan, church was used for a palace church such as Charlemagne’s at Aachen, (Figure 7.57) mausoleum (tomb building), or martyrium (site marking the death of a martyr, someone who died for their faith), where the placement of the altar does not need to address large crowds.

Christians in the Western Roman Empire used the basilica, or Latin cross, plan, but those in the Eastern Roman Empire, more commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, also employed the central plan, which had its origins in the circular plan, such as that used for the Pantheon. In the West, however, the circular, or central plan, church was used for a palace church such as Charlemagne’s at Aachen, (Figure 7.57) mausoleum (tomb building), or martyrium (site marking the death of a martyr, someone who died for their faith), where the placement of the altar does not need to address large crowds.

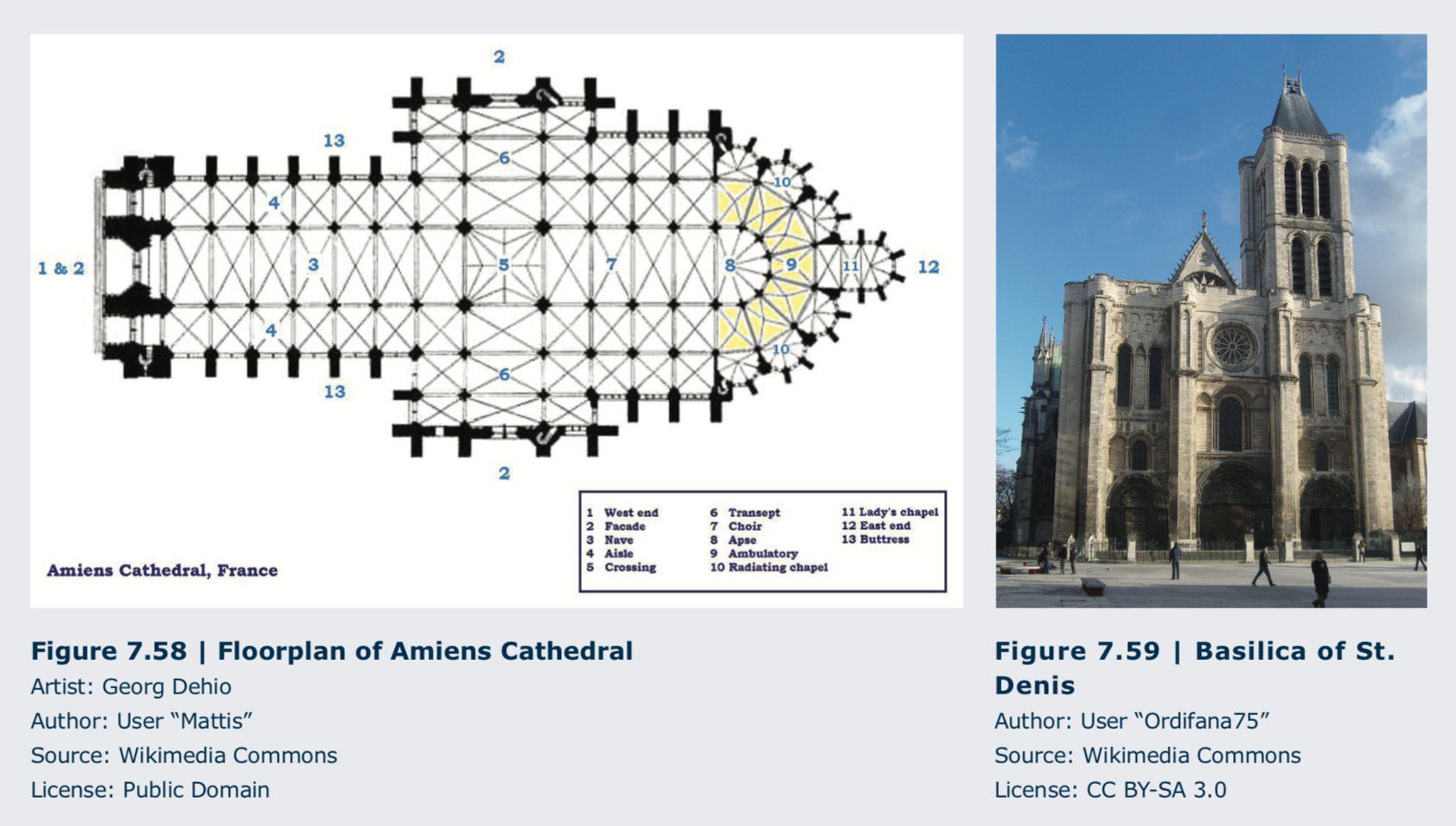

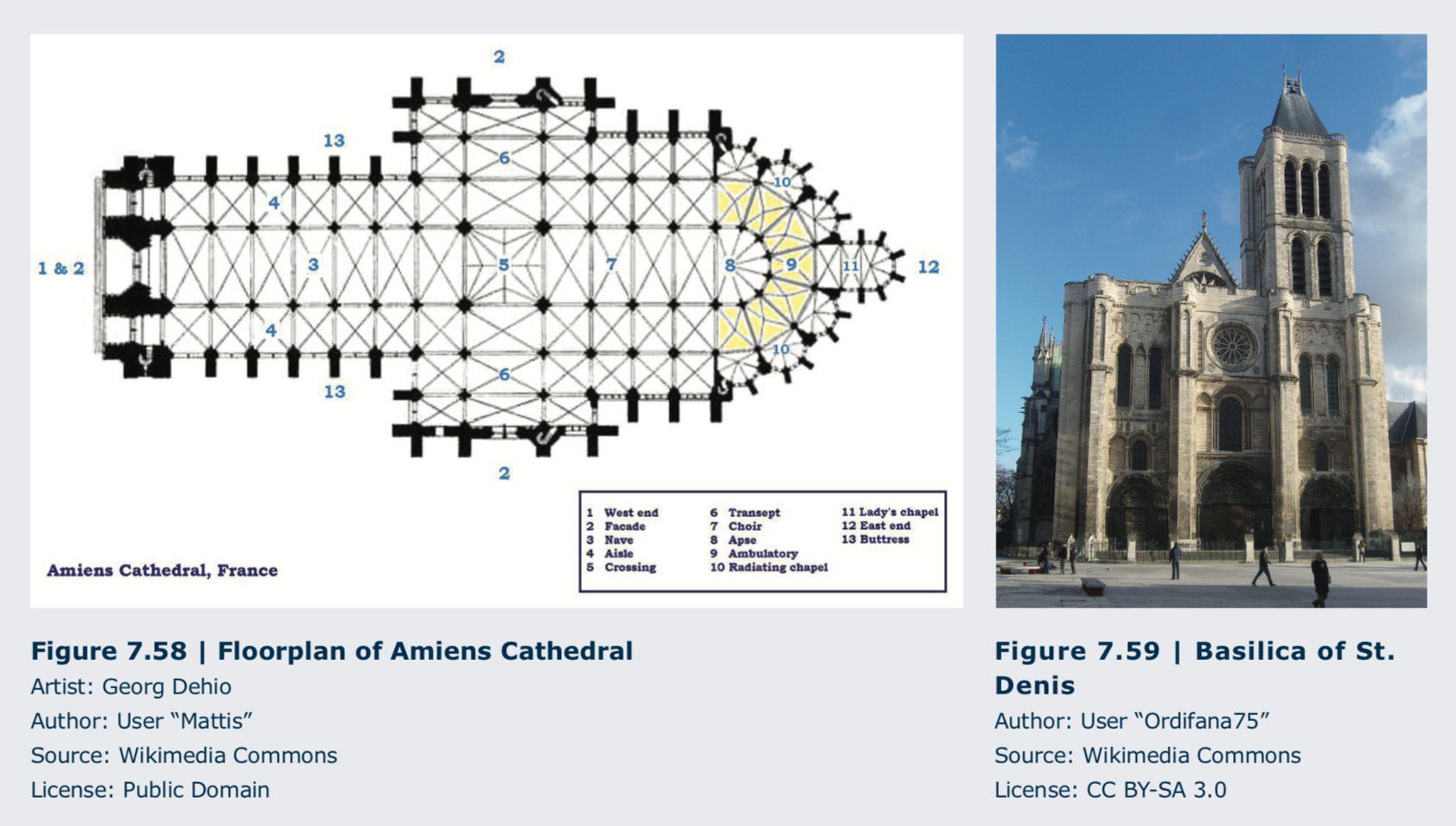

Perhaps the most familiar basilica or Latin Cross churches are those in the Gothic style in Europe that began in 1144. (Figure 7.58) When these structures were being built, they were not called “Gothic.” Instead they were called “opus francigenum” or “work of the Franks” because of its origination at the Abbey of Saint-Denis. The term “Gothic” was coined in the sixteenth century, originally meant as an insult, by artist and historian Giorgio Vasari (1511- 1574, Italy). He wanted to distinguish the architectural style, based on forms from ancient Greece and Rome at that time practiced in Italy, from medieval Christianity and its associations with the destruction of classical learning and culture. The Goths were Germanic tribes that he believed had invaded and destroyed the refined culture of ancient Rome. His pejorative name has persisted but without its originally negative connotation.

Perhaps the most familiar basilica or Latin Cross churches are those in the Gothic style in Europe that began in 1144. (Figure 7.58) When these structures were being built, they were not called “Gothic.” Instead they were called “opus francigenum” or “work of the Franks” because of its origination at the Abbey of Saint-Denis. The term “Gothic” was coined in the sixteenth century, originally meant as an insult, by artist and historian Giorgio Vasari (1511- 1574, Italy). He wanted to distinguish the architectural style, based on forms from ancient Greece and Rome at that time practiced in Italy, from medieval Christianity and its associations with the destruction of classical learning and culture. The Goths were Germanic tribes that he believed had invaded and destroyed the refined culture of ancient Rome. His pejorative name has persisted but without its originally negative connotation.

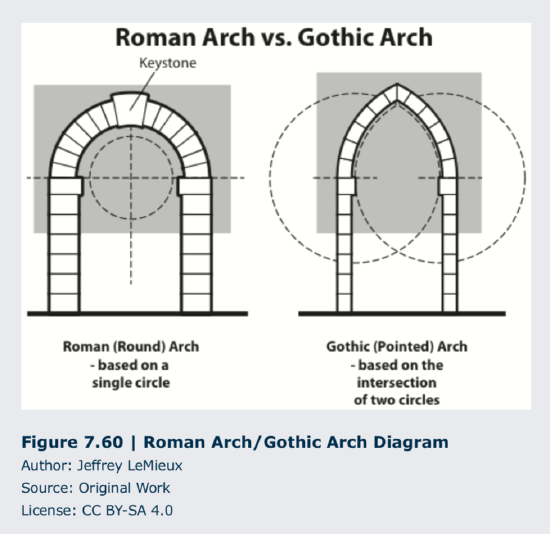

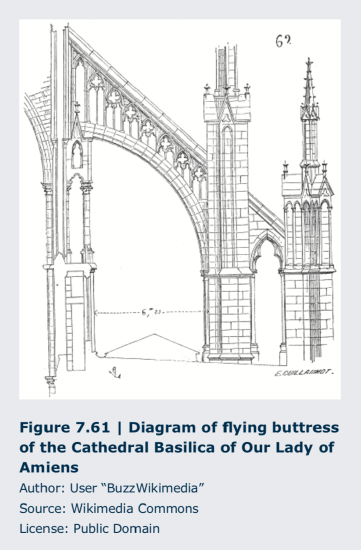

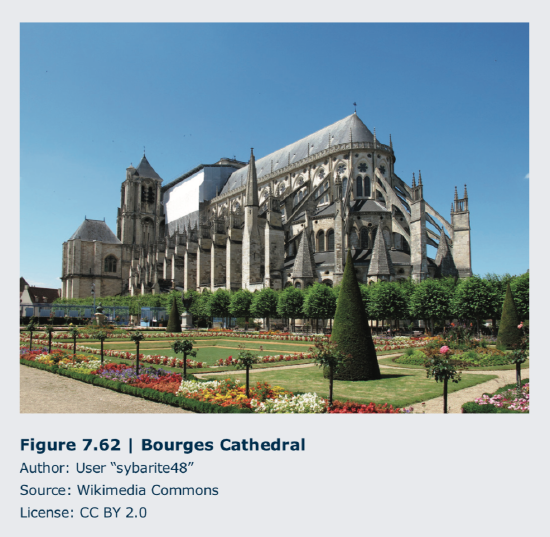

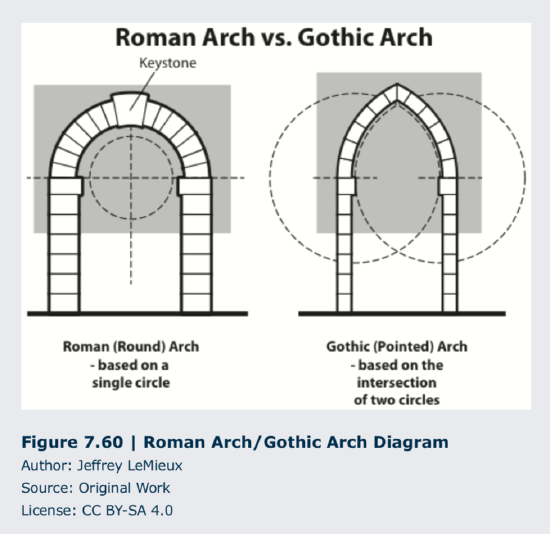

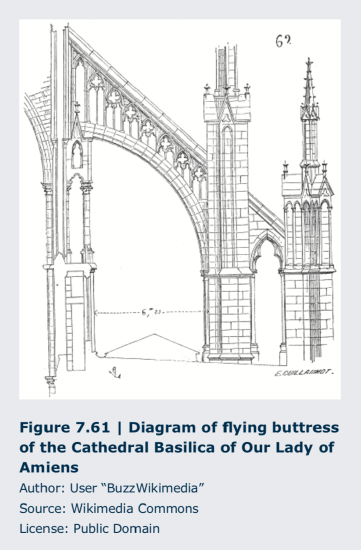

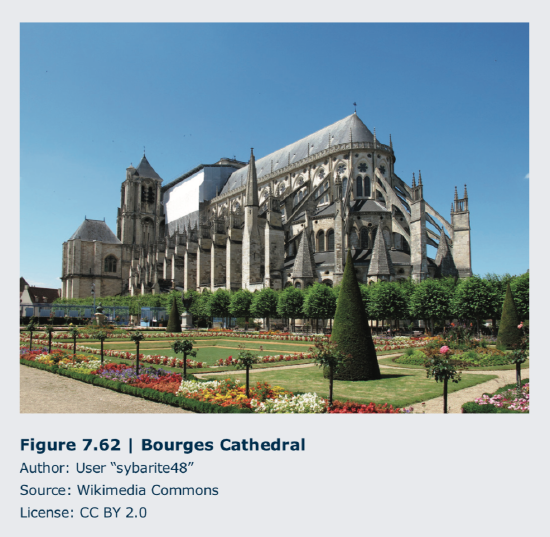

That first Gothic architecture was seen in the rebuilt choir at that Abbey Church of St. Denis, outside Paris, France, that was designed by the Abbot Suger and completed in 1144. (Figure 7.59) Several of the defining features of the Gothic cathedral were used there: the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, flying buttresses, and stained glass windows. Unlike the Roman circular arch, the Gothic or pointed arch is formed by two arcs with parallel sides. (Figure 7.60) A ribbed vault is formed at the intersection of two barrel vaults, with stone ribs sometimes added to support the weight of the vaults. The flying buttress is a load-bearing component located outside the building, connected to the upper portion of the wall in the form of an arch.

That first Gothic architecture was seen in the rebuilt choir at that Abbey Church of St. Denis, outside Paris, France, that was designed by the Abbot Suger and completed in 1144. (Figure 7.59) Several of the defining features of the Gothic cathedral were used there: the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, flying buttresses, and stained glass windows. Unlike the Roman circular arch, the Gothic or pointed arch is formed by two arcs with parallel sides. (Figure 7.60) A ribbed vault is formed at the intersection of two barrel vaults, with stone ribs sometimes added to support the weight of the vaults. The flying buttress is a load-bearing component located outside the building, connected to the upper portion of the wall in the form of an arch.

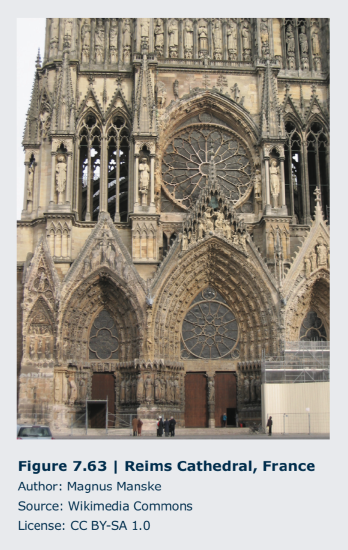

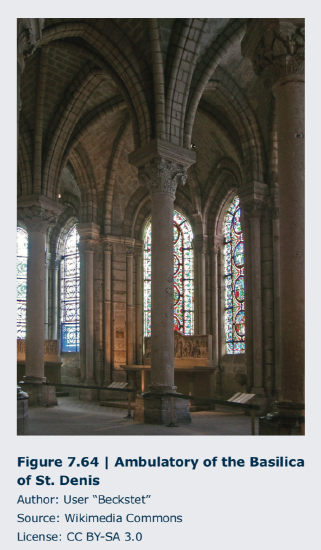

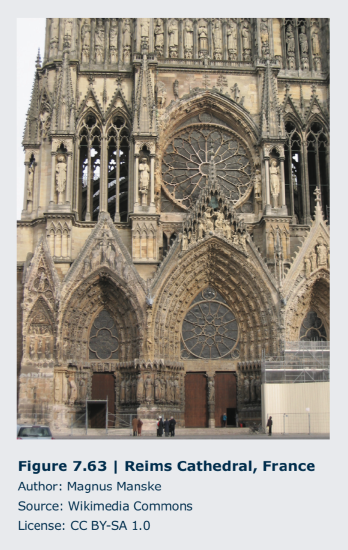

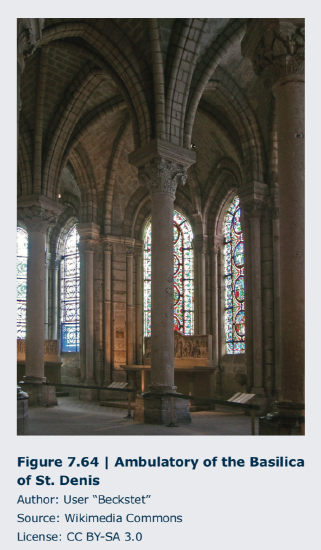

(Figures 7.61 and 7.62) The combination of the pointed arch, ribbed vault, and flying buttress allowed the height of the interior spaces to be dramatically increased and the thickness of the outside walls dramatically decreased. This development led to the widespread use of stained glass throughout the church and the addition of the rose window, a circular stained glass window dedicated to the Virgin Mary, usually found above the main portals. (Figure 7.63) The much arger number and size of windows allowed natural and multicolored light to flood the interior of formerly dark churches as was the case at St. Denis. (Figure 7.64)

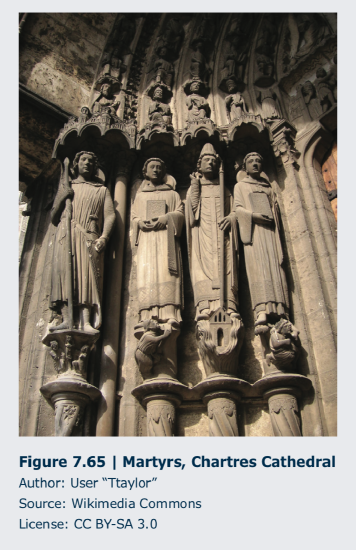

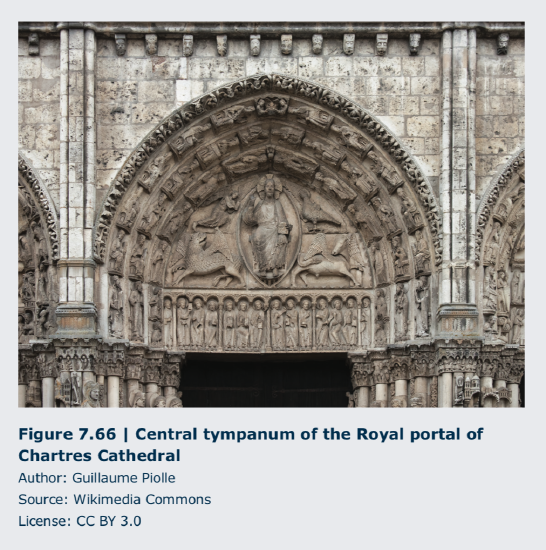

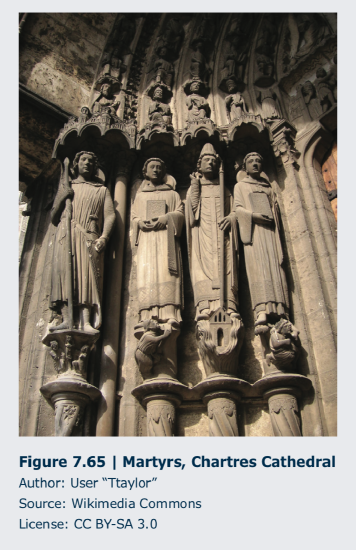

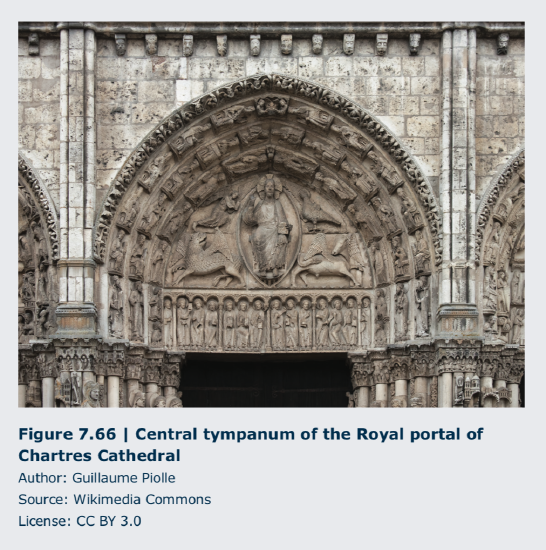

Gothic churches were built throughout continental Europe and England, with regional variations, in the center of their communities usually, especially if they were cathedrals, or Bishop’s churches. Whether viewed from a distance approaching a town or standing within the cathedral itself, the building soared above all others as it reached to the heavens. They were filled with architectural and sculptural ornamentation to teach the doctrines of the Church, Bible stories, and the accounts of Mary, the Apostles, and the other saints. Portals were especially the focus of sculptural effort. Standing figures in high relief of prophets, kings, and saints graced the sides of the jambs, or upright supports to either side of a door. (Figure 7.65) And many other sacred and secular figures, relief sculptures, often of Jesus and symbols of the Four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, were included in the tympanum above the doors. (Figure 7.66) The architects, masons, and sculptors responsible for these monumental buildings were highly skilled and creative, and Gothic cathedrals remained the dominating forms of the Western urban landscape until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when the modern structural steel skyscraper surpassed them in height and scale.

Gothic churches were built throughout continental Europe and England, with regional variations, in the center of their communities usually, especially if they were cathedrals, or Bishop’s churches. Whether viewed from a distance approaching a town or standing within the cathedral itself, the building soared above all others as it reached to the heavens. They were filled with architectural and sculptural ornamentation to teach the doctrines of the Church, Bible stories, and the accounts of Mary, the Apostles, and the other saints. Portals were especially the focus of sculptural effort. Standing figures in high relief of prophets, kings, and saints graced the sides of the jambs, or upright supports to either side of a door. (Figure 7.65) And many other sacred and secular figures, relief sculptures, often of Jesus and symbols of the Four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, were included in the tympanum above the doors. (Figure 7.66) The architects, masons, and sculptors responsible for these monumental buildings were highly skilled and creative, and Gothic cathedrals remained the dominating forms of the Western urban landscape until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when the modern structural steel skyscraper surpassed them in height and scale.

The overall effect of walking into a Gothic cathedral is to be drawn upward into a vast, light, and airy space, and to be dislocated from the physical and drawn into the spiritual. (Figure 7.67) This effect is the epitome of the Gothic Christian view that the physical and sensual world is to be ignored or even disdained in favor of chastity, spiritual awareness, and religious devotion.

The overall effect of walking into a Gothic cathedral is to be drawn upward into a vast, light, and airy space, and to be dislocated from the physical and drawn into the spiritual. (Figure 7.67) This effect is the epitome of the Gothic Christian view that the physical and sensual world is to be ignored or even disdained in favor of chastity, spiritual awareness, and religious devotion.

Christian churches of all denominations today generally follow the basilica model, but the sanctuaries vary considerably for diverse ceremonial practices. The Gothic type, with its pointed arches and glass windows that filter mystical light into the interior, is still common.

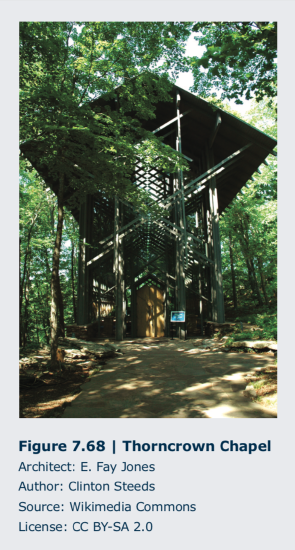

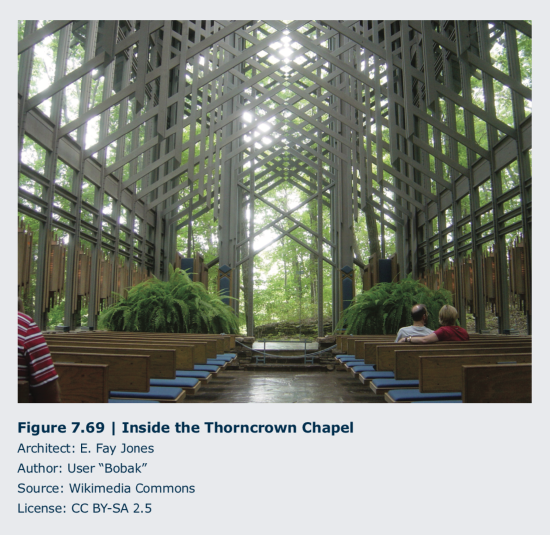

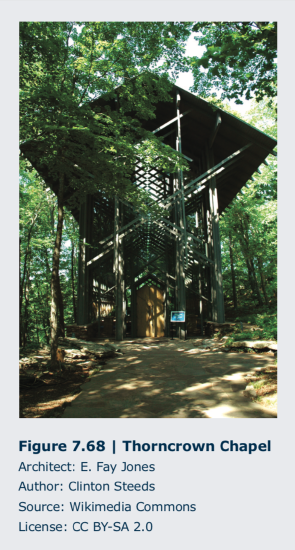

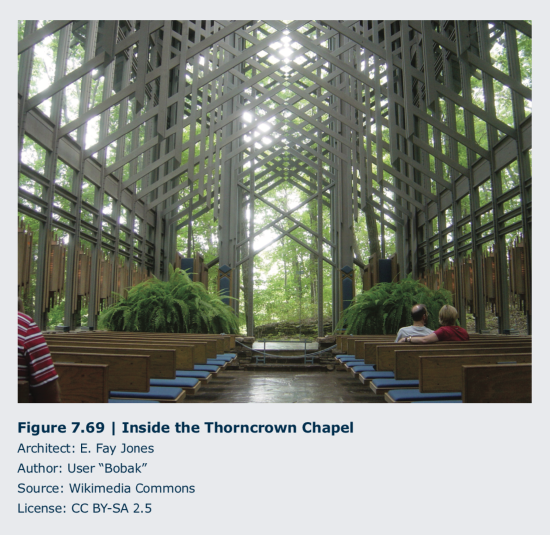

One example of an updated version is Thorncrown chapel, designed by E. Fay Jones (1921-2004, USA). Jones created a number of elegantly simple nondenominational chapels set into nature that let in diffuse light. (Figures 7.68 and 7.69) A pupil of Frank Lloyd Wright, Jones was inspired by Wright’s principles of using simple, local materials to thoroughly integrate structure and setting. The most striking feature at Thorncrown, located in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, is the structure’s light airiness. The whole of the interior for each of Jones’s chapels is a small sanctuary that seems entirely at home in the forest.

Among the earliest examples are the pyramid complexes from ancient Egypt. (Figure 7.40) The pyramids were tombs composed of millions of large stones in mathematically regular geometric structures carefully oriented to the stars. Pyramids evolved over thousands of years out of pre-Egyptian burial practices that began with placing heavy stones over gravesites to protect the occupants and their grave goods buried within.

Among the earliest examples are the pyramid complexes from ancient Egypt. (Figure 7.40) The pyramids were tombs composed of millions of large stones in mathematically regular geometric structures carefully oriented to the stars. Pyramids evolved over thousands of years out of pre-Egyptian burial practices that began with placing heavy stones over gravesites to protect the occupants and their grave goods buried within.

The building had a traditional temple front made up of columns supporting a triangular pediment. Rather than continuing into a rectangular, gable- roofed structure, however, the interior was an open circle with cult statues arrayed around its perimeter, each in a separate niche, or shallow recess in the wall. (Figure 7.48) That circular interior, acting as a drum, supported a huge domed space with an oculus, a circular opening, at its summit. Combining the circles of drum and dome creates a perfect sphere (diameter = height). (Figure 7.49) The whole of the structure was constructed using the ingenious Roman concrete, which allowed the creation of an unsupported dome greatly facilitated by the use of coffers, or recessed squares, which tremendously reduced the dome’s weight. The circle and square are not only featured in the ceiling construction, the repetition of those shapes is carried out in all of the architectural and decorative elements of the Pantheon’s interior and exterior.

The building had a traditional temple front made up of columns supporting a triangular pediment. Rather than continuing into a rectangular, gable- roofed structure, however, the interior was an open circle with cult statues arrayed around its perimeter, each in a separate niche, or shallow recess in the wall. (Figure 7.48) That circular interior, acting as a drum, supported a huge domed space with an oculus, a circular opening, at its summit. Combining the circles of drum and dome creates a perfect sphere (diameter = height). (Figure 7.49) The whole of the structure was constructed using the ingenious Roman concrete, which allowed the creation of an unsupported dome greatly facilitated by the use of coffers, or recessed squares, which tremendously reduced the dome’s weight. The circle and square are not only featured in the ceiling construction, the repetition of those shapes is carried out in all of the architectural and decorative elements of the Pantheon’s interior and exterior.

Later Indian worship structures such as the Brihadeshwara Temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, from the eleventh-century Chola Dynasty era, show the great complexity of conception of this type of worship space. (Figure 7.51) The tower at the far end is over the garba griha, or sanctuary, and as with the Temple of Horus at Edfu, there is staged progression from the profane (everyday) space to the most sacred. The whole is raised on a platform, a feature also seen in many sacred structures. Here, one must begin the approach by entering a gated courtyard, then ascend the stairs, and pass through the mandapa, or audience hall, before approaching the sanctuary. Outside the main temple but within the courtyard are subsidiary temples and shrines, as the worship is polytheistic, that is, with a great number of diverse deities.

Later Indian worship structures such as the Brihadeshwara Temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, from the eleventh-century Chola Dynasty era, show the great complexity of conception of this type of worship space. (Figure 7.51) The tower at the far end is over the garba griha, or sanctuary, and as with the Temple of Horus at Edfu, there is staged progression from the profane (everyday) space to the most sacred. The whole is raised on a platform, a feature also seen in many sacred structures. Here, one must begin the approach by entering a gated courtyard, then ascend the stairs, and pass through the mandapa, or audience hall, before approaching the sanctuary. Outside the main temple but within the courtyard are subsidiary temples and shrines, as the worship is polytheistic, that is, with a great number of diverse deities. A great deal of symbolism is associated with the form including a yasti, or mast, rising from the center of the dome that stands for an axis mundi, or axis of the world, separating the earth from the sky above. The fence and gateways are also covered with mythological carvings related to Buddhist and Hindu beliefs. (see Figure 4.23) When the Buddhist stupa form migrated to China, Japan, and elsewhere, the design evolved to include native architectural traditions resulting in the stupa form becoming the multi-tiered pagoda, a Hindu or Buddhist sacred building.

A great deal of symbolism is associated with the form including a yasti, or mast, rising from the center of the dome that stands for an axis mundi, or axis of the world, separating the earth from the sky above. The fence and gateways are also covered with mythological carvings related to Buddhist and Hindu beliefs. (see Figure 4.23) When the Buddhist stupa form migrated to China, Japan, and elsewhere, the design evolved to include native architectural traditions resulting in the stupa form becoming the multi-tiered pagoda, a Hindu or Buddhist sacred building.

As in other centers for worship we have seen, the holiest part of the church is farthest away from the most profane or public spaces. The progression from one end of the church to the other is a pro- cessional ritual, enhanced by the long rows of columns flanking the nave, the long exterior walls, that were often heavy wood or masonry structures until the Gothic era, and the filtered light that played among the structural components.

As in other centers for worship we have seen, the holiest part of the church is farthest away from the most profane or public spaces. The progression from one end of the church to the other is a pro- cessional ritual, enhanced by the long rows of columns flanking the nave, the long exterior walls, that were often heavy wood or masonry structures until the Gothic era, and the filtered light that played among the structural components. This was the case in Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, (Figure 7.56) built in the fourth century CE on the model of the Roman ba- silica type. Also based on the Roman secular model was an atrium that was placed before the entrance. The original St. Peter’s was the center of the Christian world for centuries and a model for church architecture, but it was replaced during the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods with the much grander structure that exists today in Rome.

This was the case in Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, (Figure 7.56) built in the fourth century CE on the model of the Roman ba- silica type. Also based on the Roman secular model was an atrium that was placed before the entrance. The original St. Peter’s was the center of the Christian world for centuries and a model for church architecture, but it was replaced during the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods with the much grander structure that exists today in Rome. Christians in the Western Roman Empire used the basilica, or Latin cross, plan, but those in the Eastern Roman Empire, more commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, also employed the central plan, which had its origins in the circular plan, such as that used for the Pantheon. In the West, however, the circular, or central plan, church was used for a palace church such as Charlemagne’s at Aachen, (Figure 7.57) mausoleum (tomb building), or martyrium (site marking the death of a martyr, someone who died for their faith), where the placement of the altar does not need to address large crowds.

Christians in the Western Roman Empire used the basilica, or Latin cross, plan, but those in the Eastern Roman Empire, more commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, also employed the central plan, which had its origins in the circular plan, such as that used for the Pantheon. In the West, however, the circular, or central plan, church was used for a palace church such as Charlemagne’s at Aachen, (Figure 7.57) mausoleum (tomb building), or martyrium (site marking the death of a martyr, someone who died for their faith), where the placement of the altar does not need to address large crowds. Perhaps the most familiar basilica or Latin Cross churches are those in the Gothic style in Europe that began in 1144. (Figure 7.58) When these structures were being built, they were not called “Gothic.” Instead they were called “opus francigenum” or “work of the Franks” because of its origination at the Abbey of Saint-Denis. The term “Gothic” was coined in the sixteenth century, originally meant as an insult, by artist and historian Giorgio Vasari (1511- 1574, Italy). He wanted to distinguish the architectural style, based on forms from ancient Greece and Rome at that time practiced in Italy, from medieval Christianity and its associations with the destruction of classical learning and culture. The Goths were Germanic tribes that he believed had invaded and destroyed the refined culture of ancient Rome. His pejorative name has persisted but without its originally negative connotation.

Perhaps the most familiar basilica or Latin Cross churches are those in the Gothic style in Europe that began in 1144. (Figure 7.58) When these structures were being built, they were not called “Gothic.” Instead they were called “opus francigenum” or “work of the Franks” because of its origination at the Abbey of Saint-Denis. The term “Gothic” was coined in the sixteenth century, originally meant as an insult, by artist and historian Giorgio Vasari (1511- 1574, Italy). He wanted to distinguish the architectural style, based on forms from ancient Greece and Rome at that time practiced in Italy, from medieval Christianity and its associations with the destruction of classical learning and culture. The Goths were Germanic tribes that he believed had invaded and destroyed the refined culture of ancient Rome. His pejorative name has persisted but without its originally negative connotation. That first Gothic architecture was seen in the rebuilt choir at that Abbey Church of St. Denis, outside Paris, France, that was designed by the Abbot Suger and completed in 1144. (Figure 7.59) Several of the defining features of the Gothic cathedral were used there: the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, flying buttresses, and stained glass windows. Unlike the Roman circular arch, the Gothic or pointed arch is formed by two arcs with parallel sides. (Figure 7.60) A ribbed vault is formed at the intersection of two barrel vaults, with stone ribs sometimes added to support the weight of the vaults. The flying buttress is a load-bearing component located outside the building, connected to the upper portion of the wall in the form of an arch.

That first Gothic architecture was seen in the rebuilt choir at that Abbey Church of St. Denis, outside Paris, France, that was designed by the Abbot Suger and completed in 1144. (Figure 7.59) Several of the defining features of the Gothic cathedral were used there: the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, flying buttresses, and stained glass windows. Unlike the Roman circular arch, the Gothic or pointed arch is formed by two arcs with parallel sides. (Figure 7.60) A ribbed vault is formed at the intersection of two barrel vaults, with stone ribs sometimes added to support the weight of the vaults. The flying buttress is a load-bearing component located outside the building, connected to the upper portion of the wall in the form of an arch.

Gothic churches were built throughout continental Europe and England, with regional variations, in the center of their communities usually, especially if they were cathedrals, or Bishop’s churches. Whether viewed from a distance approaching a town or standing within the cathedral itself, the building soared above all others as it reached to the heavens. They were filled with architectural and sculptural ornamentation to teach the doctrines of the Church, Bible stories, and the accounts of Mary, the Apostles, and the other saints. Portals were especially the focus of sculptural effort. Standing figures in high relief of prophets, kings, and saints graced the sides of the jambs, or upright supports to either side of a door. (Figure 7.65) And many other sacred and secular figures, relief sculptures, often of Jesus and symbols of the Four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, were included in the tympanum above the doors. (Figure 7.66) The architects, masons, and sculptors responsible for these monumental buildings were highly skilled and creative, and Gothic cathedrals remained the dominating forms of the Western urban landscape until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when the modern structural steel skyscraper surpassed them in height and scale.

Gothic churches were built throughout continental Europe and England, with regional variations, in the center of their communities usually, especially if they were cathedrals, or Bishop’s churches. Whether viewed from a distance approaching a town or standing within the cathedral itself, the building soared above all others as it reached to the heavens. They were filled with architectural and sculptural ornamentation to teach the doctrines of the Church, Bible stories, and the accounts of Mary, the Apostles, and the other saints. Portals were especially the focus of sculptural effort. Standing figures in high relief of prophets, kings, and saints graced the sides of the jambs, or upright supports to either side of a door. (Figure 7.65) And many other sacred and secular figures, relief sculptures, often of Jesus and symbols of the Four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, were included in the tympanum above the doors. (Figure 7.66) The architects, masons, and sculptors responsible for these monumental buildings were highly skilled and creative, and Gothic cathedrals remained the dominating forms of the Western urban landscape until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when the modern structural steel skyscraper surpassed them in height and scale.

The overall effect of walking into a Gothic cathedral is to be drawn upward into a vast, light, and airy space, and to be dislocated from the physical and drawn into the spiritual. (Figure 7.67) This effect is the epitome of the Gothic Christian view that the physical and sensual world is to be ignored or even disdained in favor of chastity, spiritual awareness, and religious devotion.

The overall effect of walking into a Gothic cathedral is to be drawn upward into a vast, light, and airy space, and to be dislocated from the physical and drawn into the spiritual. (Figure 7.67) This effect is the epitome of the Gothic Christian view that the physical and sensual world is to be ignored or even disdained in favor of chastity, spiritual awareness, and religious devotion.