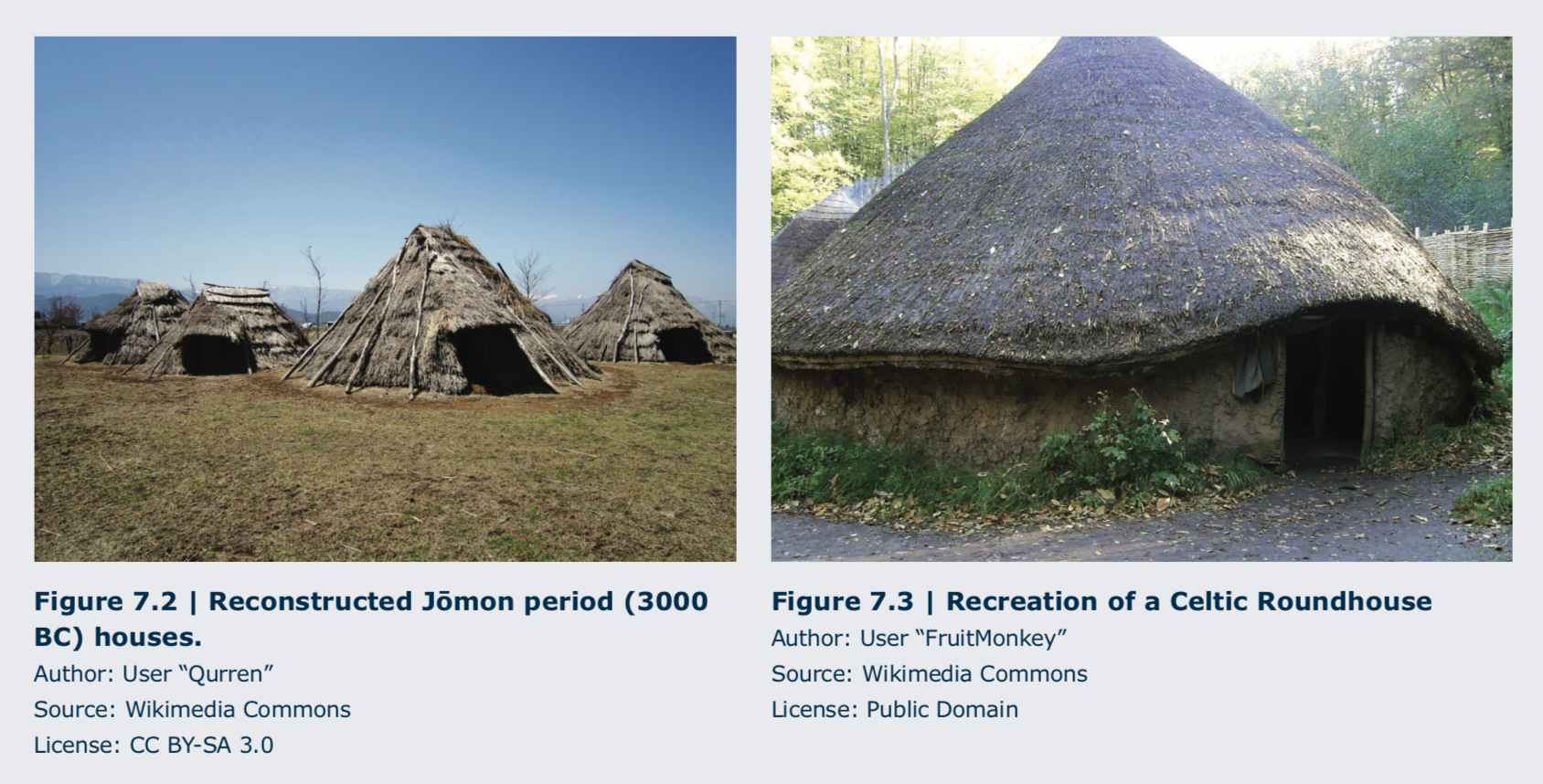

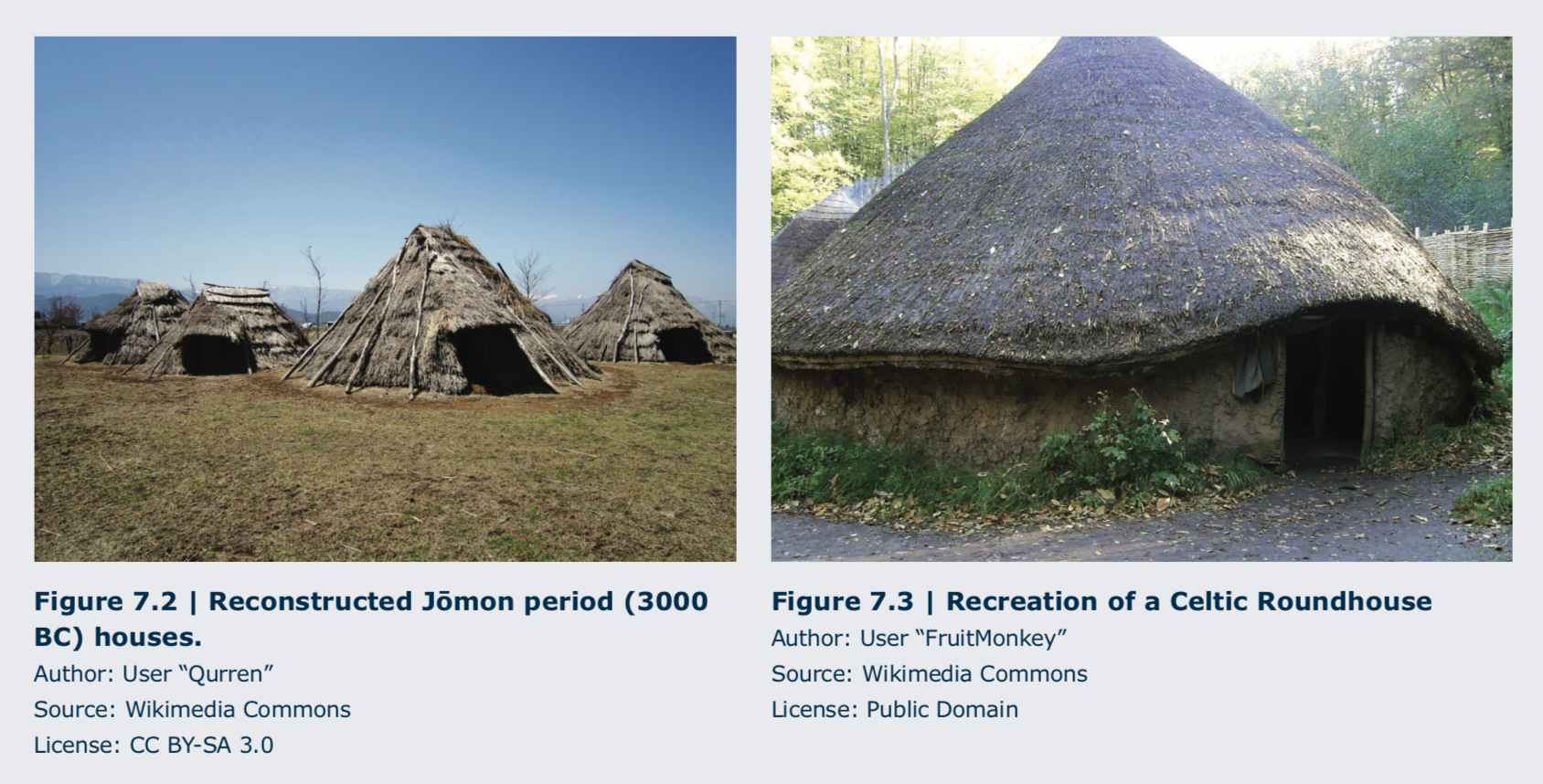

The earliest types of shelters were likely caves found by humans as they wandered to hunt and gather food and to find refuge from bad weather or pursuing creatures. The first independently standing structures were made of materials that were impermanent, that is, those found in nature sticks, bones, animal pelts and fashioned to create a covered space apparently as a protection from the elements. We have little evidence left for us to know fully how they were built and used, but some vestiges do remain that have enabled scholars to make reconstructions. (Figure 7.2)

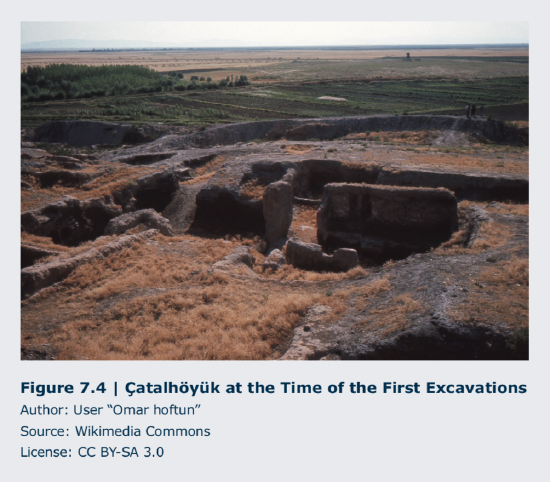

As people became more settled, domesticated animals, and cultivated crops, they developed such construction techniques as wattle-and-daub (sticks covered with mud), rammed earth (moist dirt and sand or gravel compressed into a temporary frame), and clay bricks (unfired and fired that developed alongside their evolving techniques for creating pottery vessels). (Drawing depicting architectural structure of Chinese round houses: arthistoryworlds.org/wp- includes/images/nhatau.jpg) (Figure 7.3)

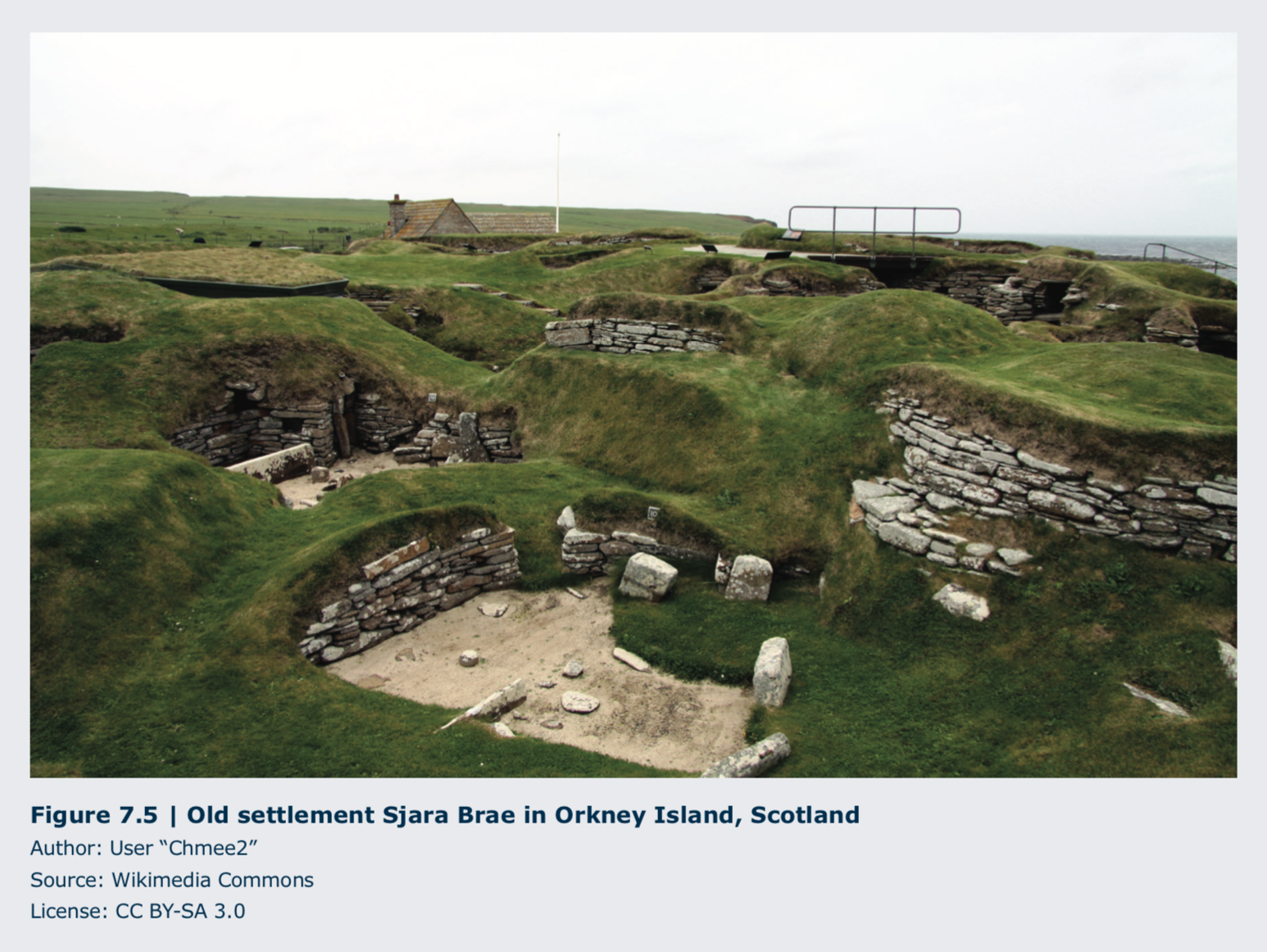

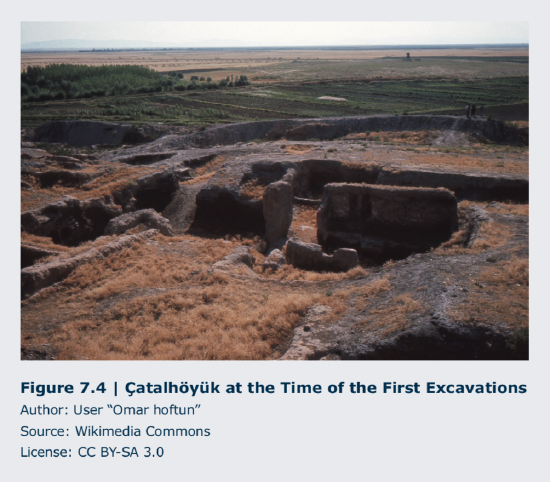

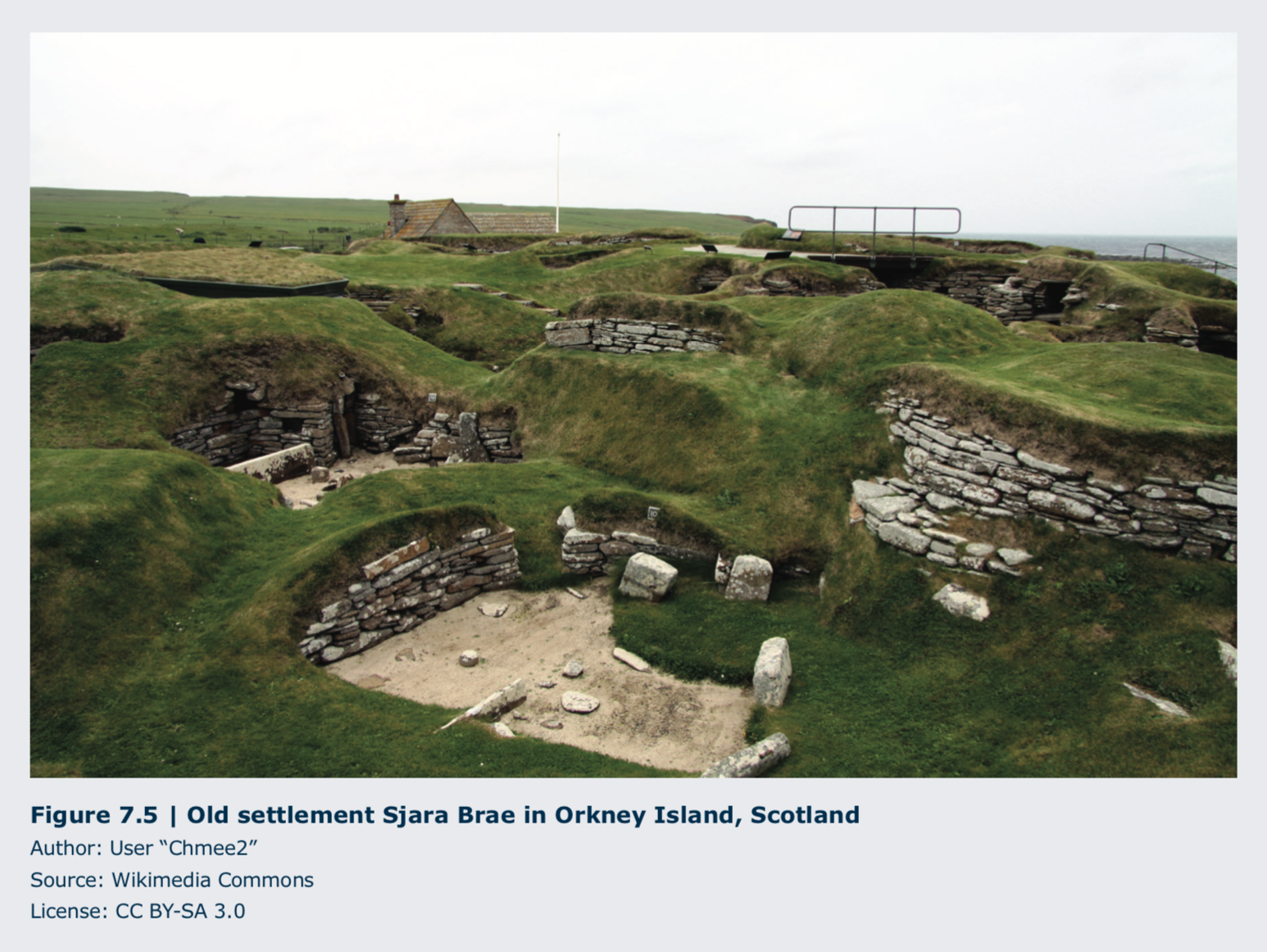

They used these methods for communal living centers such as the village of Catalhöyük in modern Turkey (7,500-5,700 BCE), including common walls so that the clustered houses supported one another. (Figure 7.4) Such building methods addressed security issues by confining entry into living spaces to openings in the roofs, with ladders that could be retracted to foil trespassers. All of these types had certain common features to meet such everyday needs as warmth, cooking, sleeping, and storage, and were usually centered around a hearth with provision for smoke ventilation. Catalhöyük also included rooms that may have been for other common purposes, varying from shrines to serving as bakeries. The use of stone for building structures began in prehistoric times, and an example of such a structure can be seen the Scottish village of Skara Brae (3,180-2,500 BCE). The walls were made of stacked stone while entryways and some of the furniture were created using the post-and-lintel method. (Figure 7.5) Because of the harsh northern climate, the structures were partially underground for protection from the elements. Additionally, covered walkways were created to facilitate movement among its eight units. Seven of theseunits apparently accommodated a family or small group, while the eighth was a common room, perhaps a workshop. In addition to cultivating crops, these villagers likely herded, fished, and hunted for food. Stone furnishing such as seating, beds, storage spaces, and other items within the single-room units were around a central fire pit. (Figure 7.6)

With these basic methods, the humble shelter types of the Neolithic Age (c. 7,000-c. 1,700 BCE) and overlapping Chalcolithic (Copper) Age (c. 5,500-c. 1,700 BCE) provided a foundation for buildings of every sort used throughout history (with considerable elaboration of residential structures for the powerful and wealthy). Material choices eventually expanded to include first wood, brick, and stone, and later concrete and metal.

With these basic methods, the humble shelter types of the Neolithic Age (c. 7,000-c. 1,700 BCE) and overlapping Chalcolithic (Copper) Age (c. 5,500-c. 1,700 BCE) provided a foundation for buildings of every sort used throughout history (with considerable elaboration of residential structures for the powerful and wealthy). Material choices eventually expanded to include first wood, brick, and stone, and later concrete and metal.

Residential palaces appeared by the time of the two great early civilizations of the Ancient Near East, Mesopotamia and Egypt, as well as those of the Aegean Sea: Crete, Cyclades, and mainland Greece prior to the development of the Greek Empire. The Palace at Knossos on the island of Crete was a grand residence for rulers of the Minoan civilization; the palace was built c. 1,700 BCE, after an earlier structure was destroyed by an earthquake, and abandoned

between 1,380 and 1,100 BCE.

(Drawing of Knossos: res.cloudinary.com/hrscywv4p/...sos_vsyfng.jpg) The sprawling complex included residential areas, throne rooms, a central courtyard, and food storage magazines for crops and seafood used in the commercial trading, an important industry and mainstay in sustaining the people. (Floorplan of Residential Palace: classconnection.s3.amazonaws.com/16/ flashcards/3907016/jpg/aafxpid0-1419F6BAD180C1BB19F.jpg) An island civilization, the Minoans were in the rare position of not having to protect themselves from enemies. The Palace at Knossos and similar structures on Crete were not fortified, that is, built behind solid walls and gates to hold off invaders. The palaces were instead built with windows and colonnades, or covered rows of columns, on their exteriors, allowing free circulation of light and air.

Another palace complex, that of Neo-Assyrian King Sargon II (ruled 722-705 BCE) at Dur- Sharrukin, today Khorsabad in Iran, was clearly much more militaristic in character, evident by the surrounding defensive walls that strictly controlled access to the royal precincts. (Figure 7.7) Even after passage through a complex and imposing gateway, one had to cross guarded courtyards and passageways to approach the king’s throne room. The structural presence was one of imposing power, as you can see from the enormous towered main portal. (Figure 7.8) To intimidate the visitor, interior decorations further asserted the mighty and ferocious nature of Sargon II with wall carvings depicting victorious battles. The complex also included temples for worship of the deities as well as quarters for high-ranking officials and servants.

Another palace complex, that of Neo-Assyrian King Sargon II (ruled 722-705 BCE) at Dur- Sharrukin, today Khorsabad in Iran, was clearly much more militaristic in character, evident by the surrounding defensive walls that strictly controlled access to the royal precincts. (Figure 7.7) Even after passage through a complex and imposing gateway, one had to cross guarded courtyards and passageways to approach the king’s throne room. The structural presence was one of imposing power, as you can see from the enormous towered main portal. (Figure 7.8) To intimidate the visitor, interior decorations further asserted the mighty and ferocious nature of Sargon II with wall carvings depicting victorious battles. The complex also included temples for worship of the deities as well as quarters for high-ranking officials and servants.

Later developments for residences include apartment buildings for urban dwellers; such multi-family dwellings have taken many forms over time, and we can view an early type, from the second-century CE Roman port town of OstiaAntica, called an insula, which is Latin for “island.” (Figure 7.9) In middle-class “apartments” such as these, there were stores and vendors’ stalls on the ground floor facing the street. In some versions, the lower floors were for the wealthier people, while upper floors decreased in cost and desirability. The basic ideas of how to accommodate multi-family living were established by this time and have remained similar since. What has changed over time are the material and decorations used, styles adopted, provisions for electricity, water, and sewage management, and eventually zoning policies that would dictate locations, sizes, required provisions for safety, and density of occupation.

Later developments for residences include apartment buildings for urban dwellers; such multi-family dwellings have taken many forms over time, and we can view an early type, from the second-century CE Roman port town of OstiaAntica, called an insula, which is Latin for “island.” (Figure 7.9) In middle-class “apartments” such as these, there were stores and vendors’ stalls on the ground floor facing the street. In some versions, the lower floors were for the wealthier people, while upper floors decreased in cost and desirability. The basic ideas of how to accommodate multi-family living were established by this time and have remained similar since. What has changed over time are the material and decorations used, styles adopted, provisions for electricity, water, and sewage management, and eventually zoning policies that would dictate locations, sizes, required provisions for safety, and density of occupation.

Private homes existed for the middle class and wealthy in towns and in the countryside; the latter were called villas whether they were primary residences or vacation homes. A private home in town might also have shops around its perimeter, but the accommodations for family life, entertainment, and conducting the owner’s business were generally contained in a single floor layout. (Diagram of Roman Villa: http://michellemoran.com/CD/Roman-Villa.jpg) After passing through an entry from the street, one entered the atrium, a courtyard with a peristyle, a row of columns within a building often supporting a porch, left open to the sky with a pool in the center to catch rainwater. A private garden was in a second area open to the elements. The mild

climate led to provisions for a good measure of outdoor living as well as fresh air and sunlight during much of the year, even including indoor and outdoor dining rooms. There were rooms for sleeping, storage, and household work off the atrium and garden, as well as a space for worship, known as the lararium. (Figure 7.10) Here, two Lares, or household gods, flank an ancestor figure; the snake below symbolizes fertility and prosperity.

Roman royalty had grand palaces, and we have good evidence of such from the retirement compound created for the Emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE) in Split set on the Bay of Aspalathos in the Roman province of Dalmatia, today Croatia. (Figure 7.11) The walled precincts with defensive watchtowers and fortified gateways included housing for his military garrison, a central peristyle courtyard, three temples, and his mausoleum, the building housing his tomb. The design, perhaps fitting for the aggressive persecutor of Christians and retired general, was quite militaristic in many ways, resembling a Roman military encampment, or castrum. The private and public imperial areas were luxurious by contrast. Like most palace complexes, provisions were made to house soldiers and servants, and it was lavishly decorated throughout with frescos, sculptures, and mosaics, images or designs created on a wall or floor made up of small pieces of stone, tile, or glass.

While the locations for palaces were always strategically selected, the rationale was not always defensive in character. When Charlemagne selected Aachen, Germany, as the site for his main palace (he had several), among the attractions were its centralized site within his growing empire and the healing waters of the natural spa there. In examining the reconstruction of his complex, you will notice the baths, shown to the left of the palace complex, are an important feature, as they had been in Roman society. (Figure 7.12) He had a large audience hall, a grand portal, courtyards, housing, and an impressive palace chapel, which is the major structure still standing. (see Figures 3.13 and 7.64)

The church was an important statement for this model Christian ruler, and although it has been enlarged from its original central plan design, the struc- ture still carries notable features that were both impressive and influential for later medieval church architecture. Charlemagne’s throne was positioned on the gallery level, an upper level overlooking the floor below. (Figure 7.13) The throne was above the entrance to the church, with an enormous “window of appearance” above the portal facing out into the atrium courtyard, where Charlemagne could address his Christian subjects gathered there. This emphasis on the western entryway was developed into the grand western facades of Romanesque and Gothic churches.

The church was an important statement for this model Christian ruler, and although it has been enlarged from its original central plan design, the struc- ture still carries notable features that were both impressive and influential for later medieval church architecture. Charlemagne’s throne was positioned on the gallery level, an upper level overlooking the floor below. (Figure 7.13) The throne was above the entrance to the church, with an enormous “window of appearance” above the portal facing out into the atrium courtyard, where Charlemagne could address his Christian subjects gathered there. This emphasis on the western entryway was developed into the grand western facades of Romanesque and Gothic churches.

The Doge’s (Duke’s) Palace in Venice is another impressive statement of rulership wed to Christian leadership. (Figure 7.14) With its façade on the waterfront, the church of San Marco sitting directly behind it, state offices located across from it, and the communal, open-ended piazza, or courtyard, between them, the palace literally connects the secular, religious, social, and political realms of Venetian life. (Figure 7.15)

Public courtyards at the heart of cities became typical during the Italian Renaissance, as did private, interior court-yards in the center of Italian homes for rulers, wealthy aristocrats, and high church officials. As an official governmental center and residence, this Venetian palace included private quarters for the Doge along with meeting rooms and council chambers, all richly decorated with marble, stucco, and fresco and including iconographic themes related to Venice, its history, and civic identity.

Public courtyards at the heart of cities became typical during the Italian Renaissance, as did private, interior court-yards in the center of Italian homes for rulers, wealthy aristocrats, and high church officials. As an official governmental center and residence, this Venetian palace included private quarters for the Doge along with meeting rooms and council chambers, all richly decorated with marble, stucco, and fresco and including iconographic themes related to Venice, its history, and civic identity.

In Japan, the fourteenth century Himeji Castle, built as a fort by the samurai Akamatsu Norimura, was situated dramatically atop Himeyana Hill. (Figure 7.16) Though a defensive posture was its primary motive, the great beauty and lyrical appearance of its curved walls and rooflines are its predominant effects. It has been called the “white heron” in response to the impression it gives of a great bird about to take flight. The complex, again, has many purposes and comprises eighty-three different structures. The grounds include huge warehouses, lush gardens, and intricate mazes. Despite its fairytale looks, its defensive systems are complex and effective, including moats, keeps, gates, towers, turrets, and mounts and brackets for a variety of weapons. It has withstood numerous attacks and natural disasters over the centuries.

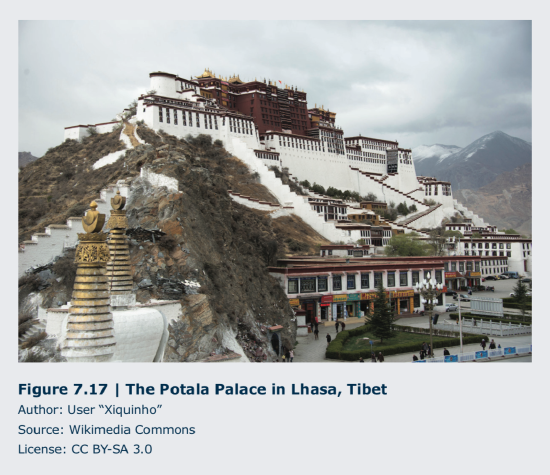

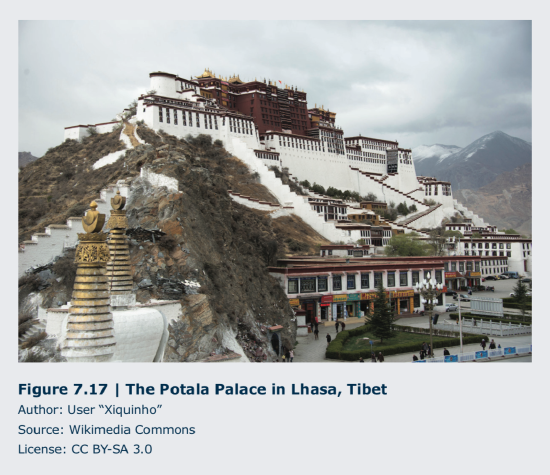

The final such royal complex we will explore is the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet, established in 1645 by the fifth Dalai Lama; the palace functioned as the spiritual and governmental center for Tibetan Buddhism until the fourteenth and current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso (b. 1935), fled for political refuge in 1959. (Figure 7.17) The basic purpose of the palace was that of a Buddhist monastery; its original foundation was centered on two chapels of historical and spiritual significance to the order of monks. The palace is named after Mount Potalaka, the mythical abode of the Bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara, and the paradisiac implications are meaningful to devotees.

As at Himeji, the hillside is a striking component of its appearance, and the enormous complex makes a very dramatic presentation. Indeed, whether intended for defensive purposes or not, its imposing appearance is often a very important feature for royal architecture. The impression of this palace’s organic relationship to the mountain is enhanced by its sloping walls, flat roofs, and numerous stairways that lead to its various structures. The complex includes living quarters for the Dalai Lama and the monks as well as governmental offices, a seminary, assembly halls, shrines, libraries, storage rooms, and numerous chapels. It includes statues and portraits of historical and spiritual leaders and many devotional and didactic depictions painted on walls and banners, and works for meditation and prayer. Burial mounds and tombs contain the remains of lamas and important scriptures.

The residential structures of the wealthy of previous eras have often been lost to us; however, we can examine some of the aristocratic family homes of the last several centuries to gain insight into some of the additional trends for creating dwellings that go far beyond the need for simple shelter and that show some of the design ideas devised by artists and architects. The house created for Lord Burlington in 1729 in Chiswick, England, is a good example of the Neo-Palladian style of architecture. (Figure 7.18) Andrea Palladio (1508-1580, Italy), a Venetian Renaissance architect, deeply studied ancient Greek and Roman architecture and architectural theory and developed new designs based on those but better fit to the means, methods, and needs of his day. His ideas were popular and have remained widely influential throughout the West to this day.

The residential structures of the wealthy of previous eras have often been lost to us; however, we can examine some of the aristocratic family homes of the last several centuries to gain insight into some of the additional trends for creating dwellings that go far beyond the need for simple shelter and that show some of the design ideas devised by artists and architects. The house created for Lord Burlington in 1729 in Chiswick, England, is a good example of the Neo-Palladian style of architecture. (Figure 7.18) Andrea Palladio (1508-1580, Italy), a Venetian Renaissance architect, deeply studied ancient Greek and Roman architecture and architectural theory and developed new designs based on those but better fit to the means, methods, and needs of his day. His ideas were popular and have remained widely influential throughout the West to this day.

Lord Burlington created his neo-Palladian villa design under the influence of Palladio’s ideas and those of other related designers. The basic idea here derives from a combination of a Greek temple front and a Roman dome, here supported by an octagonal drum, or circular or multisided base. Lord Burlington planned the house to showcase his fine collection of pictures and furniture and his architectural library as well as to provide comfort for his family living there. Great attention was paid to the surrounding gardens, and their design was very much a part of the overall scheme. Inspired by Roman gardens, they were designed by his friend William Kent (c. 1685-1748, England), an architect and early landscape architect, and included classicizing statues and miniature temples of a sort that were popular in English gardens of the day, thereby providing interesting and restful stopping points to a refreshing stroll outdoors. The logic and order of the layout of the building and grounds as well as the villa’s sense of grandeur led to its admiration and emulation by other builders who sought a similar elegance.

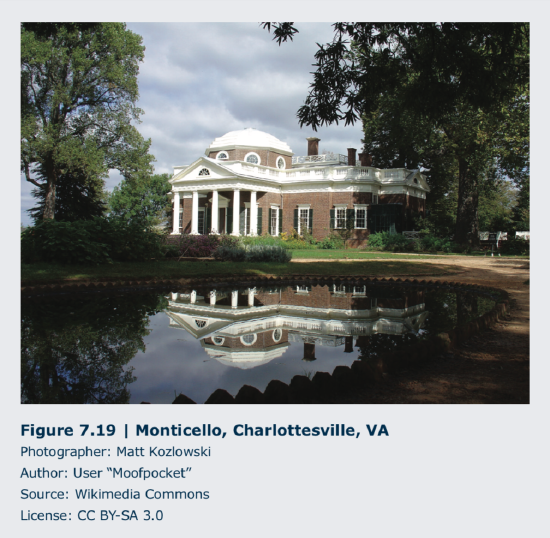

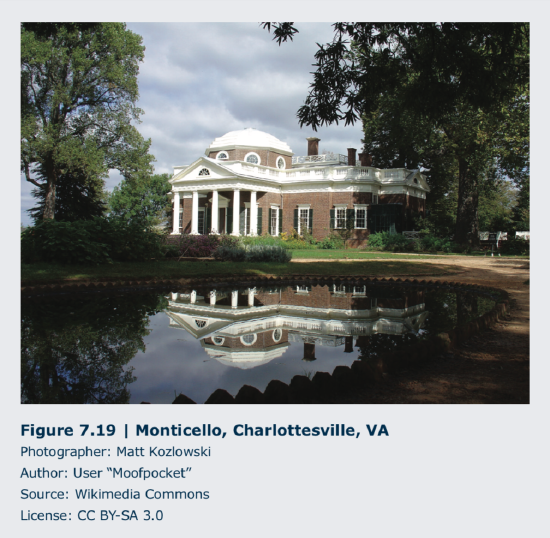

The Neo-Palladian style was carried to the United States by Thomas Jefferson for the campus of the University of Virginia, the state capitol of Virginia, and his own home of Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia. (Figure 7.19) Jefferson adapted ideas he gathered while U.S. Ambassador to France by using humbler materials such as the red brick made from local clay that he considered a better choice for a less pretentious statement than marble or limestone. At Monticello, he also brought the structure lower to the ground and added a wooden balustrade, a railing supported by upright supports, to the roofline. Nonetheless, its Palladian design origins are clear. The interior of the house is full of provisions for Jefferson’s notable intellectual and work habits such as his bedroom that opened into his office, his workrooms, and his collections of American artifacts.

The Neo-Palladian style was carried to the United States by Thomas Jefferson for the campus of the University of Virginia, the state capitol of Virginia, and his own home of Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia. (Figure 7.19) Jefferson adapted ideas he gathered while U.S. Ambassador to France by using humbler materials such as the red brick made from local clay that he considered a better choice for a less pretentious statement than marble or limestone. At Monticello, he also brought the structure lower to the ground and added a wooden balustrade, a railing supported by upright supports, to the roofline. Nonetheless, its Palladian design origins are clear. The interior of the house is full of provisions for Jefferson’s notable intellectual and work habits such as his bedroom that opened into his office, his workrooms, and his collections of American artifacts.

In the United States of the late nineteenth-century Gilded Age (c. 1870-1900), a time of rapid technological, commercial, and economic expansion, wealthy industrialists built enormous mansions in cities and at the seaside resorts or mountain retreats they favored. Among these, the Vanderbilt family (whose wealth came from shipping and railroads) commissioned several notable residences, mostly in the French-inspired Beaux Arts style, a period and style known in the U.S. as the American Renaissance (1876-1917).

One of these residences was The Breakers in Newport, Rhode Island, a lavish resort area replete with such structures. (Figure 7.20) The oceanfront house, designed by Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895, USA), has seventy rooms on five floors and covers nearly an acre of land on a thirteen-acre lot with elaborate gardens. It was built with the most lavish material such as marble and wood from around the world and was decorated with rich and sumptuous furniture, fittings, and valuable artwork, as can be seen here in the library. (Figure 7.21) Clearly a residential structure of this type went far beyond the simple needs of housing to shelter a family from the elements and served to make a very grand and ostentatious statement of wealth and power.

By contrast to design ideas of the architects who catered to the wealthiest Americans, a new conception for providing living space came into being in the early twentieth century with Frank Lloyd Wright, who developed what he called the Prairie Style. He sought to counter the blocky forms that had become the standard for American homes with a structural sweep that hugged the ground, echoed the landscape, and fostered communication between the spaces in the house and the natural elements around it.

Perhaps the epitome of this thinking was realized in Wright’s design for Falling Water, a western Pennsylvania mountain home he created for the Kaufmann family of Pittsburgh. (Figure 7.22) At their request, he incorporated elements of their favorite recreation spot into the design: the rocky outcrop where they held picnics is in the living room, and the adjacent Bear Run waterfall pours out beneath the house’s cantilevered terraces, self-supporting rigid structure projecting from the wall. Like most of Wright’s houses, the place has flowing interior space, a great number of windows, and abundant natural light, as well as carefully coordinated use of stone and wood to incorporate the structure into the natural setting.

With these basic methods, the humble shelter types of the Neolithic Age (c. 7,000-c. 1,700 BCE) and overlapping Chalcolithic (Copper) Age (c. 5,500-c. 1,700 BCE) provided a foundation for buildings of every sort used throughout history (with considerable elaboration of residential structures for the powerful and wealthy). Material choices eventually expanded to include first wood, brick, and stone, and later concrete and metal.

With these basic methods, the humble shelter types of the Neolithic Age (c. 7,000-c. 1,700 BCE) and overlapping Chalcolithic (Copper) Age (c. 5,500-c. 1,700 BCE) provided a foundation for buildings of every sort used throughout history (with considerable elaboration of residential structures for the powerful and wealthy). Material choices eventually expanded to include first wood, brick, and stone, and later concrete and metal.

Another palace complex, that of Neo-Assyrian King Sargon II (ruled 722-705 BCE) at Dur- Sharrukin, today Khorsabad in Iran, was clearly much more militaristic in character, evident by the surrounding defensive walls that strictly controlled access to the royal precincts. (Figure 7.7) Even after passage through a complex and imposing gateway, one had to cross guarded courtyards and passageways to approach the king’s throne room. The structural presence was one of imposing power, as you can see from the enormous towered main portal. (Figure 7.8) To intimidate the visitor, interior decorations further asserted the mighty and ferocious nature of Sargon II with wall carvings depicting victorious battles. The complex also included temples for worship of the deities as well as quarters for high-ranking officials and servants.

Another palace complex, that of Neo-Assyrian King Sargon II (ruled 722-705 BCE) at Dur- Sharrukin, today Khorsabad in Iran, was clearly much more militaristic in character, evident by the surrounding defensive walls that strictly controlled access to the royal precincts. (Figure 7.7) Even after passage through a complex and imposing gateway, one had to cross guarded courtyards and passageways to approach the king’s throne room. The structural presence was one of imposing power, as you can see from the enormous towered main portal. (Figure 7.8) To intimidate the visitor, interior decorations further asserted the mighty and ferocious nature of Sargon II with wall carvings depicting victorious battles. The complex also included temples for worship of the deities as well as quarters for high-ranking officials and servants. Later developments for residences include apartment buildings for urban dwellers; such multi-family dwellings have taken many forms over time, and we can view an early type, from the second-century CE Roman port town of OstiaAntica, called an insula, which is Latin for “island.” (Figure 7.9) In middle-class “apartments” such as these, there were stores and vendors’ stalls on the ground floor facing the street. In some versions, the lower floors were for the wealthier people, while upper floors decreased in cost and desirability. The basic ideas of how to accommodate multi-family living were established by this time and have remained similar since. What has changed over time are the material and decorations used, styles adopted, provisions for electricity, water, and sewage management, and eventually zoning policies that would dictate locations, sizes, required provisions for safety, and density of occupation.

Later developments for residences include apartment buildings for urban dwellers; such multi-family dwellings have taken many forms over time, and we can view an early type, from the second-century CE Roman port town of OstiaAntica, called an insula, which is Latin for “island.” (Figure 7.9) In middle-class “apartments” such as these, there were stores and vendors’ stalls on the ground floor facing the street. In some versions, the lower floors were for the wealthier people, while upper floors decreased in cost and desirability. The basic ideas of how to accommodate multi-family living were established by this time and have remained similar since. What has changed over time are the material and decorations used, styles adopted, provisions for electricity, water, and sewage management, and eventually zoning policies that would dictate locations, sizes, required provisions for safety, and density of occupation.

The church was an important statement for this model Christian ruler, and although it has been enlarged from its original central plan design, the struc- ture still carries notable features that were both impressive and influential for later medieval church architecture. Charlemagne’s throne was positioned on the gallery level, an upper level overlooking the floor below. (Figure 7.13) The throne was above the entrance to the church, with an enormous “window of appearance” above the portal facing out into the atrium courtyard, where Charlemagne could address his Christian subjects gathered there. This emphasis on the western entryway was developed into the grand western facades of Romanesque and Gothic churches.

The church was an important statement for this model Christian ruler, and although it has been enlarged from its original central plan design, the struc- ture still carries notable features that were both impressive and influential for later medieval church architecture. Charlemagne’s throne was positioned on the gallery level, an upper level overlooking the floor below. (Figure 7.13) The throne was above the entrance to the church, with an enormous “window of appearance” above the portal facing out into the atrium courtyard, where Charlemagne could address his Christian subjects gathered there. This emphasis on the western entryway was developed into the grand western facades of Romanesque and Gothic churches. Public courtyards at the heart of cities became typical during the Italian Renaissance, as did private, interior court-yards in the center of Italian homes for rulers, wealthy aristocrats, and high church officials. As an official governmental center and residence, this Venetian palace included private quarters for the Doge along with meeting rooms and council chambers, all richly decorated with marble, stucco, and fresco and including iconographic themes related to Venice, its history, and civic identity.

Public courtyards at the heart of cities became typical during the Italian Renaissance, as did private, interior court-yards in the center of Italian homes for rulers, wealthy aristocrats, and high church officials. As an official governmental center and residence, this Venetian palace included private quarters for the Doge along with meeting rooms and council chambers, all richly decorated with marble, stucco, and fresco and including iconographic themes related to Venice, its history, and civic identity.

The residential structures of the wealthy of previous eras have often been lost to us; however, we can examine some of the aristocratic family homes of the last several centuries to gain insight into some of the additional trends for creating dwellings that go far beyond the need for simple shelter and that show some of the design ideas devised by artists and architects. The house created for Lord Burlington in 1729 in Chiswick, England, is a good example of the Neo-Palladian style of architecture. (Figure 7.18) Andrea Palladio (1508-1580, Italy), a Venetian Renaissance architect, deeply studied ancient Greek and Roman architecture and architectural theory and developed new designs based on those but better fit to the means, methods, and needs of his day. His ideas were popular and have remained widely influential throughout the West to this day.

The residential structures of the wealthy of previous eras have often been lost to us; however, we can examine some of the aristocratic family homes of the last several centuries to gain insight into some of the additional trends for creating dwellings that go far beyond the need for simple shelter and that show some of the design ideas devised by artists and architects. The house created for Lord Burlington in 1729 in Chiswick, England, is a good example of the Neo-Palladian style of architecture. (Figure 7.18) Andrea Palladio (1508-1580, Italy), a Venetian Renaissance architect, deeply studied ancient Greek and Roman architecture and architectural theory and developed new designs based on those but better fit to the means, methods, and needs of his day. His ideas were popular and have remained widely influential throughout the West to this day. The Neo-Palladian style was carried to the United States by Thomas Jefferson for the campus of the University of Virginia, the state capitol of Virginia, and his own home of Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia. (Figure 7.19) Jefferson adapted ideas he gathered while U.S. Ambassador to France by using humbler materials such as the red brick made from local clay that he considered a better choice for a less pretentious statement than marble or limestone. At Monticello, he also brought the structure lower to the ground and added a wooden balustrade, a railing supported by upright supports, to the roofline. Nonetheless, its Palladian design origins are clear. The interior of the house is full of provisions for Jefferson’s notable intellectual and work habits such as his bedroom that opened into his office, his workrooms, and his collections of American artifacts.

The Neo-Palladian style was carried to the United States by Thomas Jefferson for the campus of the University of Virginia, the state capitol of Virginia, and his own home of Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia. (Figure 7.19) Jefferson adapted ideas he gathered while U.S. Ambassador to France by using humbler materials such as the red brick made from local clay that he considered a better choice for a less pretentious statement than marble or limestone. At Monticello, he also brought the structure lower to the ground and added a wooden balustrade, a railing supported by upright supports, to the roofline. Nonetheless, its Palladian design origins are clear. The interior of the house is full of provisions for Jefferson’s notable intellectual and work habits such as his bedroom that opened into his office, his workrooms, and his collections of American artifacts.