9.9: Destruction, looting, and trafficking

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 261797

- Smarthistory

- Smarthistory

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Mesa Verde and the preservation of Ancestral Puebloan heritage

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Wanted: stunning view

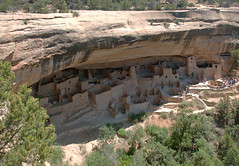

Imagine living in a home built into the side of a cliff. The Ancestral Puebloan peoples (formerly known as the Anasazi) did just that in some of the most remarkable structures still in existence today. Beginning after 1000-1100 C.E., they built more than 600 structures (mostly residential but also for storage and ritual) into the cliff faces of the Four Corners region of the United States (the southwestern corner of Colorado, northwestern corner of New Mexico, northeastern corner of Arizona, and southeastern corner of Utah). The dwellings depicted here are located in what is today southwestern Colorado in the national park known as Mesa Verde (“verde” is Spanish for green and “mesa” literally means table in Spanish but here refers to the flat-topped mountains common in the southwest).

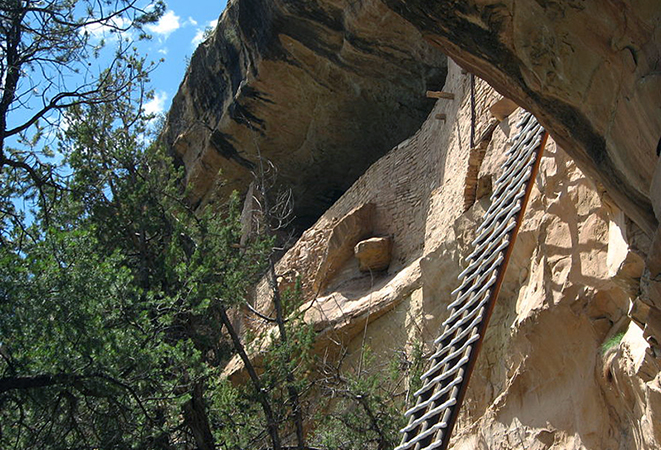

The most famous residential sites date to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Ancestral Puebloans accessed these dwellings with retractable ladders, and if you are sure footed and not afraid of heights, you can still visit some of these sites in the same way today.

To access Mesa Verde National Park, you drive up to the plateau along a winding road. People come from around the world to marvel at the natural beauty of the area as well as the archaeological remains, making it a popular tourist destination.

The twelfth- and thirteenth-century structures made of stone, mortar, and plaster remain the most intact. We often see traces of the people who constructed these buildings, such as hand or fingerprints in many of the mortar and plaster walls.

Ancestral Puebloans occupied the Mesa Verde region from about 450 C.E. to 1300 C.E. The inhabited region encompassed a far larger geographic area than is defined now by the national park, and included other residential sites like Hovenweep National Monument and Yellow Jacket Pueblo. Not everyone lived in cliff dwellings. Yellow Jacket Pueblo was also much larger than any site at Mesa Verde. It had 600–1200 rooms, and 700 people likely lived there (see link below). In contrast, only about 125 people lived in Cliff Palace (largest of the Mesa Verde sites), but the cliff dwellings are certainly among the best-preserved buildings from this time.

Cliff palace

The largest of all the cliff dwellings, Cliff Palace, has about 150 rooms and more than twenty circular rooms. Due to its location, it was well protected from the elements. The buildings ranged from one to four stories, and some hit the natural stone “ceiling.” To build these structures, people used stone and mud mortar, along with wooden beams adapted to the natural clefts in the cliff face. This building technique was a shift from earlier structures in the Mesa Verde area, which, prior to 1000 C.E., had been made primarily of adobe (bricks made of clay, sand and straw or sticks). These stone and mortar buildings, along with the decorative elements and objects found inside them, provide important insights into the lives of the Ancestral Puebloan people during the thirteenth century.

At sites like Cliff Palace, families lived in architectural units, organized around kivas (circular, subterranean rooms). A kiva typically had a wood-beamed roof held up by six engaged support columns made of masonry above a shelf-like banquette. Other typical features of a kiva include a firepit (or hearth), a ventilation shaft, a deflector (a low wall designed to prevent air drawn from the ventilation shaft from reaching the fire directly), and a sipapu, a small hole in the floor that is ceremonial in purpose. They developed from the pithouse, also a circular, subterranean room used as a living space.

Kivas continue to be used for ceremonies today by Puebloan peoples though not those within Mesa Verde National Park. In the past, these circular spaces were likely both ceremonial and residential. If you visit Cliff Palace, you will see the kivas without their roofs (see above), but in the past they would have been covered, and the space around them would have functioned as a small plaza.

Connected rooms fanned out around these plazas, creating a housing unit. One room, typically facing onto the plaza, contained a hearth. Family members most likely gathered here. Other rooms located off the hearth were most likely storage rooms, with just enough of an opening to squeeze your arm through a hole to grab anything you might need. Cliff Palace also features some unusual structures, including a circular tower. Archaeologists are still uncertain as to the exact use of the tower.

Painted murals

The builders of these structures plastered and painted murals, although what remains today is fairly fragmentary. Some murals display geometric designs, while other murals represent animals and plants.

For example, Mural 30, on the third floor of a rectangular “tower” (more accurately a room block) at Cliff Palace, is painted red against a white wall. The mural includes geometric shapes that are thought to portray the landscape. It is similar to murals inside of other cliff dwellings including Spruce Tree House and Balcony House. Scholars have suggested that the red band at the bottom symbolizes the earth while the lighter portion of the wall symbolizes the sky. The top of the red band, then, forms a kind of horizon line that separates the two. We recognize what look like triangular peaks, perhaps mountains on the horizon line. The rectangular element in the sky might relate to clouds, rain or to the sun and moon. The dotted lines might represent cracks in the earth.

The creators of the murals used paint produced from clay, organic materials, and minerals. For instance, the red color came from hematite (a red ocher). Blue pigment could be turquoise or azurite, while black was often derived from charcoal. Along with the complex architecture and mural painting, the Ancestral Puebloan peoples produced black-on-white ceramics and turquoise and shell jewelry (goods were imported from afar including shell and other types of pottery). Many of these high-quality objects and their materials demonstrate the close relationship these people had to the landscape. Notice, for example, how the geometric designs on the mugs above appear similar to those in Mural 30 at Cliff Palace.

Why build here?

From 500–1300 C.E., Ancestral Puebloans who lived at Mesa Verde were sedentary farmers and cultivated beans, squash, and corn. Corn originally came from what is today Mexico at some point during the first millennium of the Common Era. Originally most farmers lived near their crops, but this shifted in the late 1100s when people began to live near sources of water, and often had to walk longer distances to their crops.

So why move up to the cliff alcoves at all, away from water and crops? Did the cliffs provide protection from invaders? Were they defensive or were there other issues at play? Did the rock ledges have a ceremonial or spiritual significance? They certainly provide shade and protection from snow. Ultimately, we are left only with educated guesses—the exact reasons for building the cliff dwellings remain unknown to us.

Why were the cliffs abandoned?

The cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde were abandoned around 1300 C.E. After all the time and effort it took to build these beautiful dwellings, why did people leave the area? Cliff Palace was built in the twelfth century, why was it abandoned less than a hundred years later? These questions have not been answered conclusively, though it is likely that the migration from this area was due to either drought, lack of resources, violence or some combination of these. We know, for instance, that droughts occurred from 1276 to 1299. These dry periods likely caused a shortage of food and may have resulted in confrontations as resources became more scarce. The cliff dwellings remain, though, as compelling examples of how the Ancestral Puebloans literally carved their existence into the rocky landscape of today’s southwestern United States.

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Additional resources:

Yellow Jacket Pueblo reconstruction

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2 ed. Oxford History of Art series (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Elizabeth A. Newsome and Kelley Hays-Gilpin, “Spectatorship and Performance in Mural Painting, AD 1250–1500,” Religious Transformation in the Late Pre-Hispanic Pueblo World, eds. Donna Glowacki and Scott Van Keuren, Amerind Studies in Archaeology (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2011).

David Grant Noble, ed., The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Pueblo Archaeology (Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 2006).

David W. Penney, North American Indian Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

A market for looted antiquities

Several members of the cast of the film The Monuments Men made headlines for expressing the view that the British Museum should return the Elgin Marbles to Athens after their “very nice stay” of 200 years in London.

That reignited the debate around the ethics and intentions of their removal from the Parthenon in the early 19th century, as well as the controversy around what to do with them now. But whether or not the removal of the sculptures should be considered “pillage or protection”, as the Guardian put it, we might take the opportunity to reflect on other more contemporary and unambiguous examples of international cultural heritage plunder.

Demands of the art market

The international art market that deals in ancient cultural objects casts a destructive shadow. Tombs are looted, statues broken from their pedestals, and facades chainsawed off temples, all to feed a booming economic demand among connoisseurs who prize the enjoyment of the artistic attributes of cultural objects, the thrill and investment value of collection, and the social status attributed to those associated with high culture.

The source countries for these collectible objects tend to be less economically developed than the market countries and so are usually not very well equipped to protect their heritage resources against plunder. London and New York are the two biggest centers for this trade in the world, and their active art markets have over the years exerted a strong demand for the archaeological riches underground in countries like Egypt, Greece and Turkey; or pieces of temple complexes like those found in South America and South East Asia.

Estimates of the size of the illicit underworld of the international trade in art and antiquities are unreliable at present. Although figures as high as US$6 billion have been proposed, it is generally recognised that it is currently impossible to verify size estimates. Many looted antiquities are sold on the open market and their illicit origins will never be detected, let alone proved. And, as well as the public trade through auction houses and museum acquisitions which can be scrutinised to some extent, there is also a private trade between individuals, which is difficult to investigate.

Police statistics in most countries do not even have a separate category for art related thefts or seizures. They tend to lump them in with all other types of property theft. Looting in source countries happens at sites which are often remote, and in some cases undiscovered, and much looting activity is not detected or recorded by over-stretched local police forces.

All of these factors, and more, make it very difficult to know how much illicit market activity there really is. But a growing body of research has established considerable evidence to show that looting and trafficking is still a sizeable and serious issue, and one involving significant sums of money.

Cultural looting

There was a relatively uncontested free and open dealing in looted cultural objects in Britain and elsewhere running through the colonial era, supported by imperialist values, and this continued. Then, in the 1960s a sustained critique of these practices began to take hold.

Archaeologists who had experienced first-hand the looting of sites they had been working on began to reflect on the rapacious nature of the market in cultural resources. In particular, they argued that looters destroyed sites as they dug out tombs and other underground heritage, depriving researchers of the historical knowledge which the context of buried objects could give up.

Criticism of the international trade in looted antiquities mounted, and in 1970 UNESCO brought countries together under an international convention to protect the world’s cultural heritage from exploitation by market forces. This date of 1970 has over time come to be accepted as the norm for acquisition of antiquities, particularly among museums subscribing to a collective ethical code.

They now have to look for a “provenance” (ownership history) dating back to at least that date. This is obviously therefore a rule intended to reduce demand for artifacts looted in recent decades, rather than to right any perceived wrongs of a more historical nature. But not all types of buyers in the market subscribe to the 1970 norm – and our research evidence suggests the “1970 rule” is not greatly influencing aggregate buying decisions in public market settings.

Repatriation

Major dealing and collecting institutions have been implicated in the trade in illicit cultural objects, as one would expect, given that traffickers have inserted looted artifacts into the legitimate trade, where they have most value. And as the understanding of the reach of this increases, so does the trend towards “repatriation” of objects to their source countries from the world’s encyclopedic museums.

For example, in 2013 the Metropolitan Museum in New York returned two “Kneeling Attendants” to the national museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, looted originally it seems from the temple complex at the ancient Khmer capital of Koh Ker, one of Cambodia’s great heritage sites.

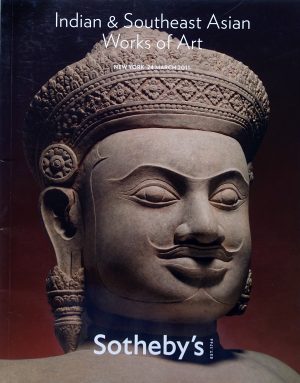

At the same time, another statue from Koh Ker has been the subject of litigation in the New York courts: the Duryodhana, offered for sale by Sotheby’s for an estimated $2m-$3m. The statue in New York was broken off at the ankles and its feet were discovered still attached to their pedestal in the Prasat Chen temple at Koh Ker.

The US Department of Justice alleged that it was torn from its base in the 1970s during the civil war which led to Khmer Rouge power – and from our fieldwork in Cambodia, we have first-hand accounts of similar looting activity from traffickers active at that time. Subsequently, it was transported to London where it was sold to a Belgian collector through the auction house Spink. Late in 2013, Sotheby’s and Cambodia concluded a settlement to the case, and the statue was returned.

The pressing question for the great museums of the world is what will happen to their repositories in a climate of greater attention to the ethics of acquisitions, present and past. This raises difficult value judgements around the wider issue of where ancient artifacts belong, the moral status of major museums in rich countries, and “who owns culture”, as the titles of several books in the field put it.

For some people, this question may invite different responses when applied to cases like the Elgin Marbles on one hand, or fresh loot on the other. For so-called “cultural internationalists,” the issue is the very moral legitimacy of countries declaring ownership of all cultural heritage. But the countries themselves would see the moral and legal elements of their title as being settled.

Market victim or complicit?

The extent to which museums, dealers, collectors and auction houses know about the illicit origins of objects they acquire – and whether they turn a blind eye or are genuinely duped by fraudulent sellers – is hotly contested. The New York dealer Frederick Schultz, for example, once president of the National Association of Dealers in Ancient, Oriental and Primitive Art, was sentenced in 2002 to nearly three years in jail and received a $50,000 fine for his part in receiving looted items from Egypt through a British smuggler named Jonathan Tokeley-Parry.

The smuggled objects had been dipped in plastic and painted to look like tourist souvenir items, thus evading Egyptian border control. The two dealers then fabricated provenance for the items in order to give them the appearance of having a legitimate ownership history, inventing a collector they called Thomas Alcock and attaching labels to the objects to suggest they were from his collection.

They even went so far as to artificially age the labels by dipping them in tea, to better support the illusion they were creating. The artifacts included a sculptural head of the 18th dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III, subsequently to be sold by Schultz for $1.2 million.

And in 1997, journalist Peter Watson published the results of his five-year investigation Sotheby’s: the Inside Story, which alleged complicity among some of the auction house’s employees in knowingly receiving looted and trafficked artifacts.

Subsequently, Sotheby’s closed the London arm of its antiquities sales department, never to re-open, in a move which was “widely interpreted” as a response to Watson’s book, and which prompted Boston University archaeology professor and long-time commentator on illicit trade issues Ricardo Elia to note that “London has been called the smuggling capital of the world.”

Against these scandalous examples of malpractice, trade representatives tend to argue that they exercise appropriate levels of “due diligence”. Criminal offenses for dealing in illicit cultural objects like the up-to-seven year prison sentence created in the UK in 2003 often require the prosecution to prove a buyer’s “knowledge or belief” of an object’s tainted history, which has proved very difficult to do. The UK law remains virtually unused.

And so the current debate raised by George Clooney, Matt Damon and Bill Murray’s thoughts on the repatriation of the Elgin Marbles is important, but for reasons which don’t tend to make their way into press reports of the controversy. The discussion around antiquities which were taken from Greece over two centuries ago is part of the context of a more immediate issue of global crime. Looting and trafficking of cultural objects is not only a problem of the past.

by Simon Mackenzie, Professor of Criminology, Law and Society, University of Glasgow (CC BY-ND 4.0)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Save Culture – end trafficking

by UNESCO

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Conflict situations and natural disasters increase the risk of theft and trafficking dramatically. Many instances of plunder, theft and trafficking of cultural objects go unseen or unsolved.

This video was produced by the UNESCO Beirut Office in the framework of the Emergency Safeguarding of the Syrian Cultural Heritage project, funded by the European Union and supported by the Flemish Government and the Government of Austria.

Produced by Keeward, Illustration, Animation and Sound Design by Squarefish

Trafficking the past

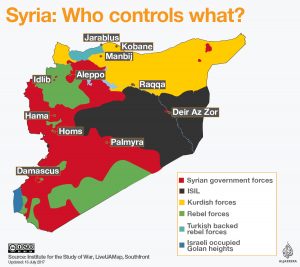

In June 2014 the Guardian newspaper ran a story claiming that the terrorist organization Daesh had made $36 million from antiquities sales in the al-Nabuk area of Syria, and that it obtained a major part of its funding from antiquities sales more generally.

Almost overnight, this story transformed the antiquities trade in the public imagination from being a crime against culture into a crime against humanity. If the headlines that followed over the following weeks and months were anything to go by, vast sums of money were being directed from the antiquities trade into the war chests of Daesh and other armed terrorist and insurgency groups. Something needed to be done. It was a compelling narrative, one that played out well with the media-malleable public, and it certainly hooked the attention of concerned policy-makers, but for many long-time experts in the field it just did not ring true.

Fantasy economics

In the first place, the idea that $36 million could be made over the period of a year or so actually within Syria was unprecedented, unbelievable even. Many studies had shown that the monetary value of antiquities close to their source is only a small and even a vanishingly small percentage of their value on the destination market in places like London and New York.

In 1972, for example, The Metropolitan Museum of Art paid antiquities dealer Robert Hecht one million dollars for a Euphronios Attic red-figure krater. The tombaroli who stole the krater from an ancient Etruscan tomb in Italy are believed to have received the equivalent of $88,000 for their labors—only nine percent of its final price. Such markups are typical. So, if the story was to be believed, antiquities worth $36 million on the ground in Syria would be worth a staggering $360 million on the destination market, perhaps much more. It was fantasy economics. There was no evidence for that kind of market activity and the reality had to be something less spectacular.

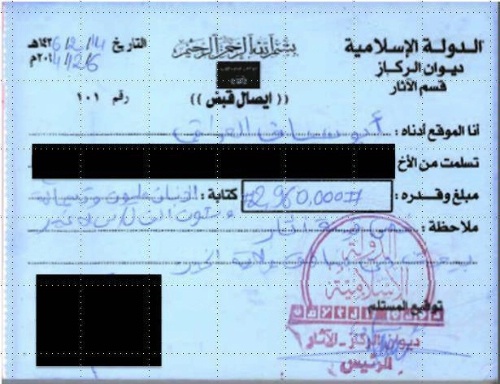

The Guardian figure was never corroborated, but a more accurate assessment was achieved when in May 2015 United States Special Forces seized a book of receipts during a raid on the Syrian headquarters of Abu Sayyaf, the head of Daesh’s antiquities division. These receipts suggested that Daesh might be making something like four million dollars a year from the antiquities trade. A large and worrying sum, but nothing like the figure first suggested, and one that would account for only about one percent of Daesh’s total income.

Antiquities trafficking is nothing new

Terrorists and insurgents profiting from antiquities trafficking was nothing new. What was new was the sensationalist reporting. In the 1990s, for example, it was well known that mujahideen and later Taliban groups inside Afghanistan were making money from the antiquities trade, but this never made the headlines.

Before that, in the 1970s, combatant factions in the Cambodian civil war, including after 1990 the Khmer Rouge, had been likewise engaged. It is believed, for example, that the Khmer general Ta Mok, the so-called “Butcher of Cambodia,” had held a central organizing role in the Cambodian antiquities trade.

During the early 1980s, until his fall from favor in 1985, Bashar al-Assad’s uncle, Rifaat al-Assad, controlled the antiquities trade in Syria, and his counterpart in Iraq was perhaps Saddam Hussein’s brother-in-law Arshad Yashin, who is said to have organized much of the looting there. Violence was a growing accompaniment to the antiquities trade during this period. In late-1990s Iraq, guards were killed in gun battles while trying to protect sites. In 2005, while transporting arrested antiquities dealers, eight Iraqi customs officers were ambushed and shot dead. So while it might be an exaggeration to report the antiquities trade as a crime against humanity, it is a violent enterprise, and one that profits armed and criminal organizations alike.

Why did we fail to protect Syria’s cultural heritage?

The real surprise and indeed outrage of the Daesh involvement with the trade was that it was happening at all. The threats posed by antiquities trafficking to cultural heritage and more broadly to society at large had been known since at least the 1960s, when the international community had supported the drafting and subsequent adoption of the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. For the first time, the antiquities trade was recognized internationally as a harmful enterprise and one that needed to be controlled. Since then, there has been a proliferation of conventions, recommendations and actions aimed at combatting the trade and protecting cultural heritage. So why, 45 years later in 2015, was the antiquities trade devastating Syrian cultural heritage? Had the international policy response failed? What had gone wrong?

A rise in consumer demand

The answers to these questions are to be found in the nature of the policy response. The antiquities trade is fueled by consumer demand. Antiquities are bought by museums and private collectors in the rich acquiring countries of the destination market.

Yet international policy has never quite come to grips with tackling demand and reducing the attractive pull of museums and collectors. Instead, its focus has been on protecting cultural heritage at source and reducing the flow of antiquities onto the destination market. Yet it is an impossible task to protect every cultural site in the world, particularly in poor countries unable to afford the required infrastructure, or in countries suffering from war or civil disturbance where public order has disintegrated. Only when collectors can be convinced to stop buying antiquities will thieves and traffickers stop selling them.

Museums in the spotlight

Back in the 1960s, when the 1970 UNESCO Convention to prevent the illegal trafficking of cultural property was being drafted, museums were believed to be the mainspring of demand. And perhaps they were. There has been a concerted effort since then to develop ethical guidelines discouraging museums from acquiring trafficked antiquities. The work of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) has been particularly notable in this regard.

Yet following investigations by Italian and Greek law enforcement authorities, the museums world was rocked during the 1990s by revelations that major US art museums had been actively acquiring stolen and trafficked antiquities. Museums such as the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York were forced to return important antiquities to Italy and Greece, including the Euphronios krater.

But the bad news didn’t stop there. In the 2010s, police and customs officials in India and the United States broke up a major trafficking operation headed by New York-based dealer Subhash Kapoor. He was shown to have sold a large Chola bronze Shiva Nataraja, which had been stolen from a temple in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu only two years earlier, to the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) for five million dollars. The NGA returned the Nataraja to India in 2014. Kapoor had sold other antiquities from the same temple thefts to Singapore’s Asian Civilizations Museum and the Toledo Museum of Art. The case triggered an independent review of the problematic histories of 36 antiquities acquired by the NGA between 1968 and 2013.

Museums, clearly, are still an important component of demand. They act materially by making big money purchases and acquisitions, but also set a moral tone when they seem to make indiscriminate collecting socially acceptable.

Booming demand

Nevertheless, by the time of Kapoor’s arrest, museums were not the only destination for trafficked antiquities. Antiquities were being touted as tangible assets for canny investors, and they had become trendy ornaments for interior-design makeovers. Antiquities from Middle Eastern countries were being marketed as “relics” from the “Holy Land,” and the meditative worth of Buddhist antiquities similarly attracted more spiritual collectors. The rapid expansion of the internet as a means for trading antiquities created a market for smaller and less-valuable pieces that would previously not have been worth looting. Demand was booming like never before, and was largely out of control.

Successful indictments and convictions of offenders for antiquities trafficking were so rare as to be almost non-existent. Even when convictions did happen, sentencing was light and failed to pose any serious deterrence. In 2012, two U.S.-based dealers pled guilty to offenses related to antiquities trafficking. One was sentenced to six months’ home confinement and one year’s probation, the other was fined $1,000. Within a couple of years, they were both back in business.

Missing evidence

Trafficked antiquities are routinely sold without documented evidence or even with fraudulent evidence of ownership history—so-called “unprovenanced” antiquities. The problems facing law enforcement authorities who must try to establish provenance were made abundantly clear in July 2017 when it was announced that Hobby Lobby had agreed to pay a $3 million forfeiture to the United States government and relinquish claims to and possession of 3,599 Iraqi antiquities bought in 2010 for 1.6 million dollars. Knowledgeable observers believed the antiquities to have been stolen from Iraq, and that someone should have faced a felony charge for the theft. But the evidence was not there. Theft could not be proved. Instead, Hobby Lobby was punished for customs violations.

Hobby Lobby is owned by the Green family, which in 2009 established the Green Collection of antiquities and other objects related to biblical history, and the Green Scholars Initiative of university academics to study them. As the 2017 forfeitures showed, much of the unprovenanced material being studied by the Green Scholars is likely to have been trafficked.

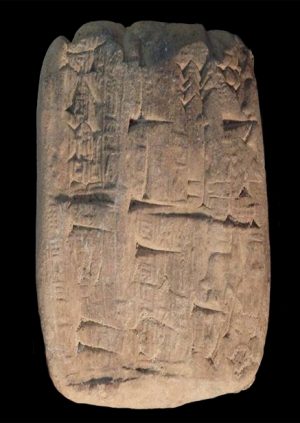

The Green scholars are not alone. A new academic industry has developed, comprised of university scholars studying suspect antiquities acquired by large private collections. Ancient manuscripts and other text-bearing antiquities, many of them from Egypt, Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, and Palestine, are particularly worthy of attention. Scholarship establishes the importance and authenticity, and thus monetary value of studied material—to the financial benefit of the collector. In 2007, for example, a U.S.-based private collector claimed a $900,000 tax deduction for a donation of 1,679 Iraqi cuneiform tablets to Cornell University. He had purchased the tablets sometime during the 1990s for $50,000. The mark-up in price must have been due to scholarly study over the intervening period that had established their importance—and their value.

How do we stop trafficking?

Antiquities trafficking damages cultural heritage worldwide, and the proceeds from trafficking fund organized crime and terrorist violence. No one has to buy unprovenanced antiquities. Antiquities collecting does not confer cultural sophistication and antiquities are not good investments. Antiquities trafficking will only stop when people stop buying them.

Additional resources:

Dr. Neil Brodie’s blog, Market of Mass Destruction

Saving Antiquities for Everyone (SAFE)

Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA)

U.S. Department of State Cultural Heritage Center

U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield

We will need Monuments Men for as long as ancient sites remain battlefields

The destruction and looting of cultural heritage has been intertwined with conflict for thousands of years. To steal an enemies’ treasures, defile their sacred places and burn their cities has been part of war throughout history. And sadly, in the modern battlefields of the ancient world, in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Egypt, and elsewhere, it continues to this day.

The Colosseum in Rome, for example, was built using spoils from the sack of the Temple of Jerusalem in AD 70. Many of the Louvre’s collections were “acquired” by Napoleon while rampaging through Europe (albeit later returned). In fact, much of Napoleon’s collection of war booty – acquired during his failed campaign in Egypt – was declared forfeit by the British victors and given to the British Museum under the Treaty of Capitulation of 1801. The Rosetta Stone, which famously enabled the deciphering of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic script, was acquired through this treaty and is still on display there today.

Although antiquities gained widespread public interest throughout the 19th and early 20th century, it was not until the Second World War that the idea of preserving them in conflict finally took hold. As Hitler’s armies advanced across Europe, he saw an opportunity to conquer not only the land and the people, but the cultures of defeated nations. Millions of artistic works and important cultural objects were seized and sent back to Germany, where Hitler took a personal interest in selecting the very best. His new Führermuseum was to be the most spectacular art museum ever built, culled from the cultural riches of the western world.

Those in command of the Allied forces were faced with a historical and cultural loss of unprecedented scale. Declaring his support for the protection of the past, the supreme Allied commander, Dwight Eisenhower, said:

Inevitably, in the path of our advance will be found historical monuments and cultural centres which symbolise to the world all that we are fighting to preserve. It is the responsibility of every commander to protect and respect these symbols wherever possible.

Enter the Monuments Men

In 1943, the Allied forces approved the formation of a new unit: the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Commission (MFAA). For the first time in history, armies went into the field with officers dedicated to protecting art and monuments during the conflict. It was going to be a tough job. Entire historic quarters in cities such as Warsaw were demolished in days and the artistic treasures of Europe were vanishing.

Just 345 men and women, with no dedicated resources, were tasked with protecting historic buildings, monuments, libraries and archives across the whole of Europe and North Africa. Most were museum staff, art historians, scholars and university professors, yet their success was incredible. They found and returned more than five million stolen objects and artworks and ensured the protection of numerous buildings, often using no more than their own ingenuity.

A part of their story is told in the new film, Monuments Men, based on author Robert Edsel’s book of the same name, by the Monuments Men Foundation, and also in the book and ensuing film The Rape of Europa. In 1951, the MFAA was disbanded as politicians drafted the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, followed by the First Protocol in 1954 and the Second Protocol in 1999 (which extended and clarified the original tenets).

The convention protects places and objects “of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people” during conflict. It argues the heritage of all sides should be protected and that warring sides should not use it or its immediate surroundings, nor direct assaults against it. It also granted suitable authority and units for its protection. Crucially, it separates the principles of military necessity from military convenience. Unfortunately, it is not widely adhered to and many of the lessons learned by the MFAA have been forgotten.

The monumental battle today

The Monument Men of today are almost all volunteers. Some are local people, such as the Syrian Association for Preserving Heritage and Ancient Landmarks, who work in Aleppo (a UNESCO World Heritage city) to try and save its monuments and buildings. Individual organisations monitor the situation. Some countries have formed voluntary national Committees of the Blue Shield.

The Blue Shield network was suggested in the Hague Convention and is the cultural equivalent of the Red Cross. It is a group of non-governmental organisations working to protect monuments, sites, museums and archives during and after conflict and natural disasters. Members are drawn from universities, museums and heritage organisations, with advisors from the Red Cross, UNESCO, the military and others.

Their objectives are to formulate and lead national and international responses to emergencies that threaten cultural property. They encourage respect for, and protection of, cultural heritage, providing training and advice. Despite the Hague Convention’s mandates, often the only military personnel who engage with cultural heritage protection do so voluntarily.

Today, 126 countries have ratified the Hague Convention, although the necessary work is rarely funded and not all the tenets are enforced. The UK has not ratified it, despite the destruction caused by the coalition invasion of Iraq in 2003. In August 2013, chemical weapons were used in Syria and intervention was discussed. Had it happened, the British military is under no obligation to protect, or even consider, any of the thousands of significant sites throughout the country, many of which date back to the earliest achievements of mankind.

Protecting cultural property is about more than old books, buildings and fine paintings. Our cultural heritage stands as the symbol of everything humanity has achieved: our finest moments and even our worst atrocities. It is the physical reminder of our past and inspiration for our future. While not every site can be saved, its loss should be a matter of necessity and never convenience. As Eisenhower stated 70 years ago, to fight without even considering it is to sacrifice everything for which we are fighting.

by Emma Cunliffe, Postgraduate Associate, Durham University (CC BY-ND 4.0)

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

What the bulldozers left behind: reclaiming Sicán’s past

by DR. SARAHH SCHER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Inverse-Face Beaker, 10th-11th century, Sicán (Lambayeque), Peru, gold, 20 x 18.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Key points:

- The Sicán culture was located on the north coast of Peru, and is sometimes referred to as Lambayeque.

- We have lost a significant amount of knowledge of Sicán culture due to systematic looting and grave-robbing. These looted objects were smuggled out of Peru and many find their way to private collections and museums in North America and Europe.

- This inverse-face beaker, made of hammered gold, shows a face in a position that would have been upside-down when it was used. This inversion may suggest the underworld, or contact with spirit forces.

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Donna Yates, Batán Grande on Trafficking Culture

Izumi Shimada, “Sicán Elite Tombs and Their Broader. Implications” (Institute of Archaeology, University College London, 1992)

Izumi Shimada, “Precious Metal Objects of the Middle Sicán,” Scientific American (2005)

Lost History: the terracotta sculpture of Djenné-Djenno

by DR. KRISTINA VAN DYKE and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Seated figure, 13th century, Mali, Inland Niger Delta (Djenné peoples), terracotta, 25.4 x 29.9cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Speakers: Dr. Kristina Van Dyke and Dr. Steven Zucker

The Looting of Cambodian Antiquities

by TESS DAVIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): The looting of ancient Cambodian antiquities from Prasat Chen, the 10th century the Khmer capital at Koh Ker ARCHES: At Risk Cultural Heritage Education Series

Additional resources:

“Sotheby’s Accused of Deceit in Sale of Khmer Statue” (The New York Times, November 13, 2012)

Cambodia Vs. Sotheby’s In A Battle Over Antiquities (from NPR)

Return of six of the nine statues looted from Cambodia (UNESCO)

Red List of Cambodian Antiquities at Risk (ICOM)

Sotheby’s Returns Looted 10th Century Statue to Cambodia

by TESS DAVIS

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Archaeologist and legal expert Tess Davis talks about Sotheby’s attempt to auction an ancient Cambodian statue that had been looted by the Khmer Rouge in 1972; and the statue’s eventual return home.

The Scourge of Looting: Trafficking Antiquities from Temple to Museum

by TESS DAVIS

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Archaeologist and legal expert Tess Davis talks about the illicit antiquities trade, and how the looting of archaeological sites in conflict zones goes to fund paramilitary groups and terrorist organizations.

To learn more about the Angkor period of Cambodia see our essay on Angkor Wat.

How a famous Greek bronze ended up in the Vatican

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Taken from Greece, confiscated by an emperor and returned to the people.

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Lysippos, Apoxyomenos, Roman marble copy after Greek bronze original dating to c. 300 B.C.E. (Vatican Museums, Rome, Italy)

Fact and fiction: The explosion of Reims Cathedral during World War I

The facts…?

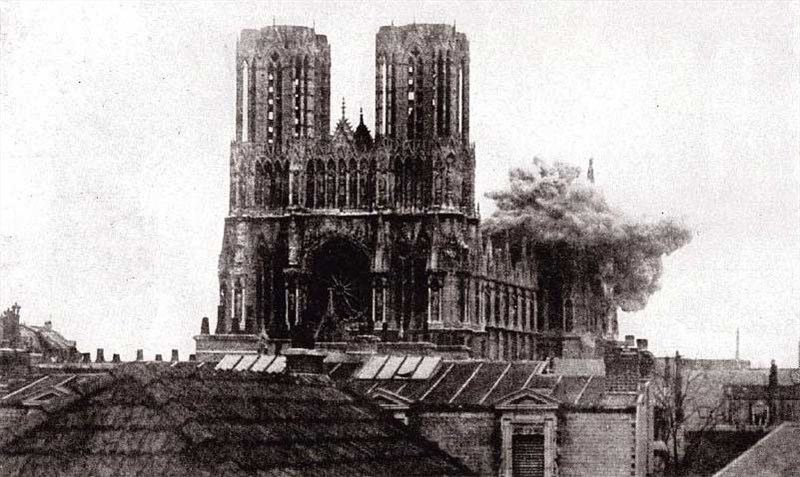

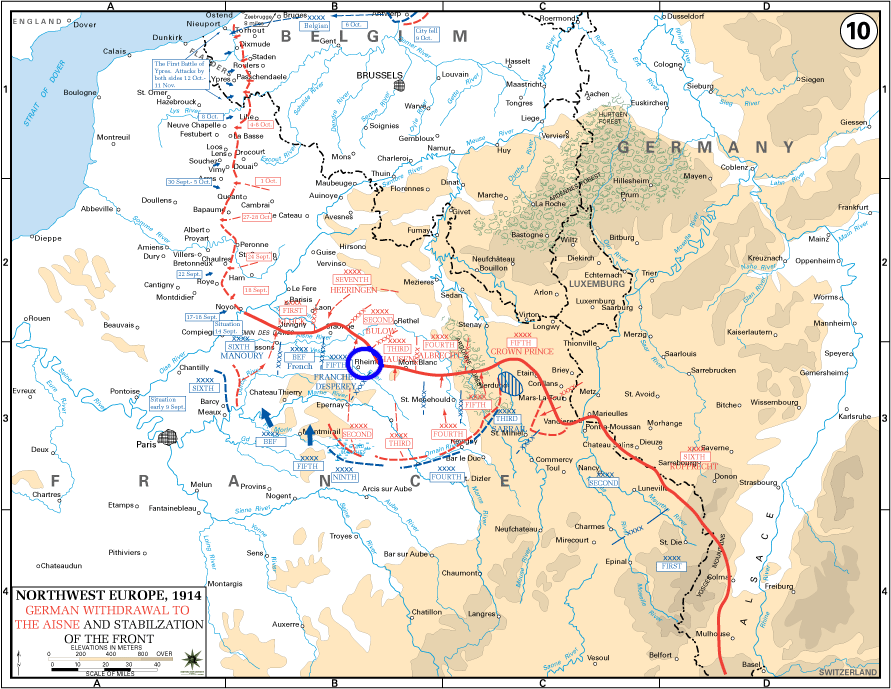

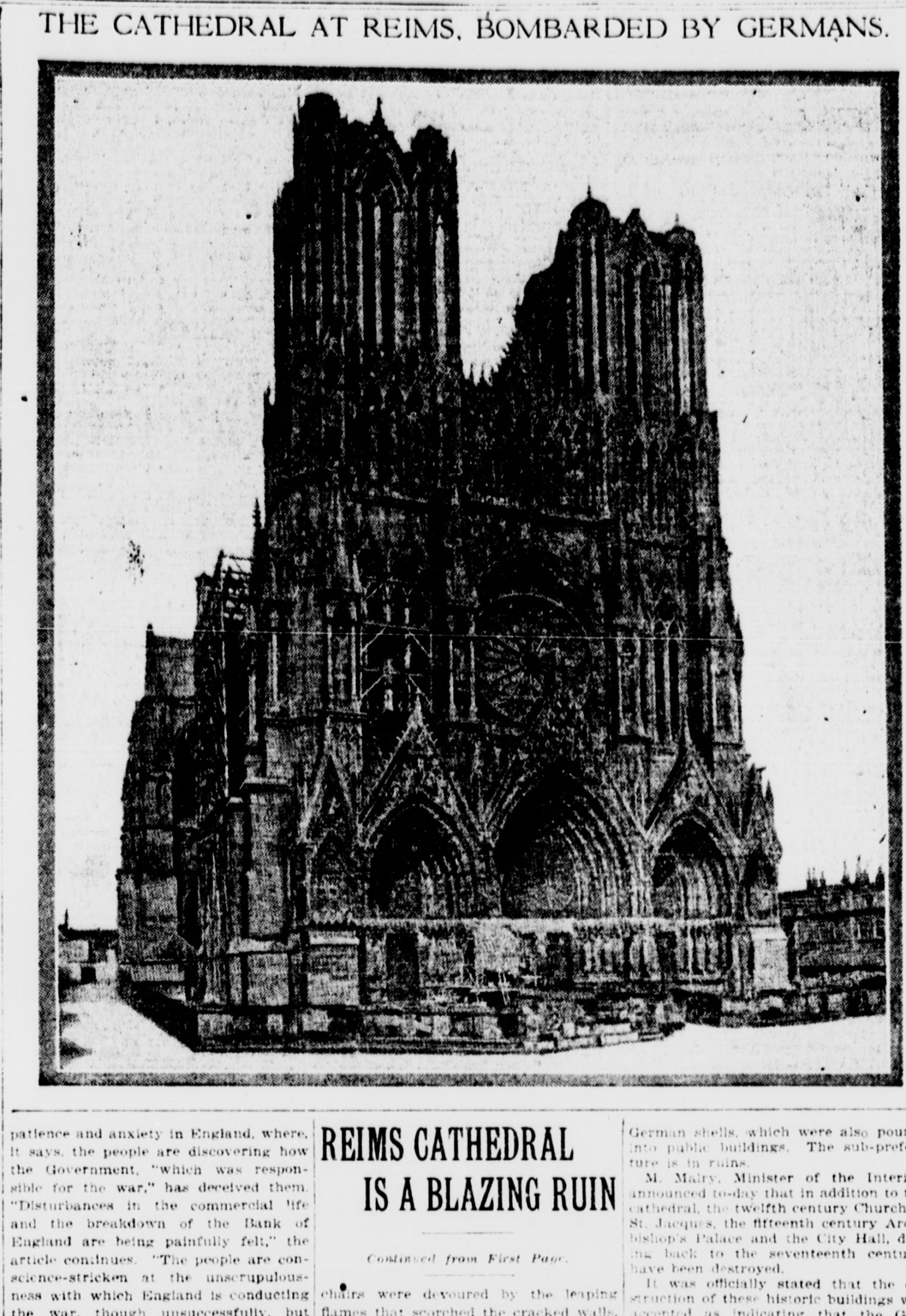

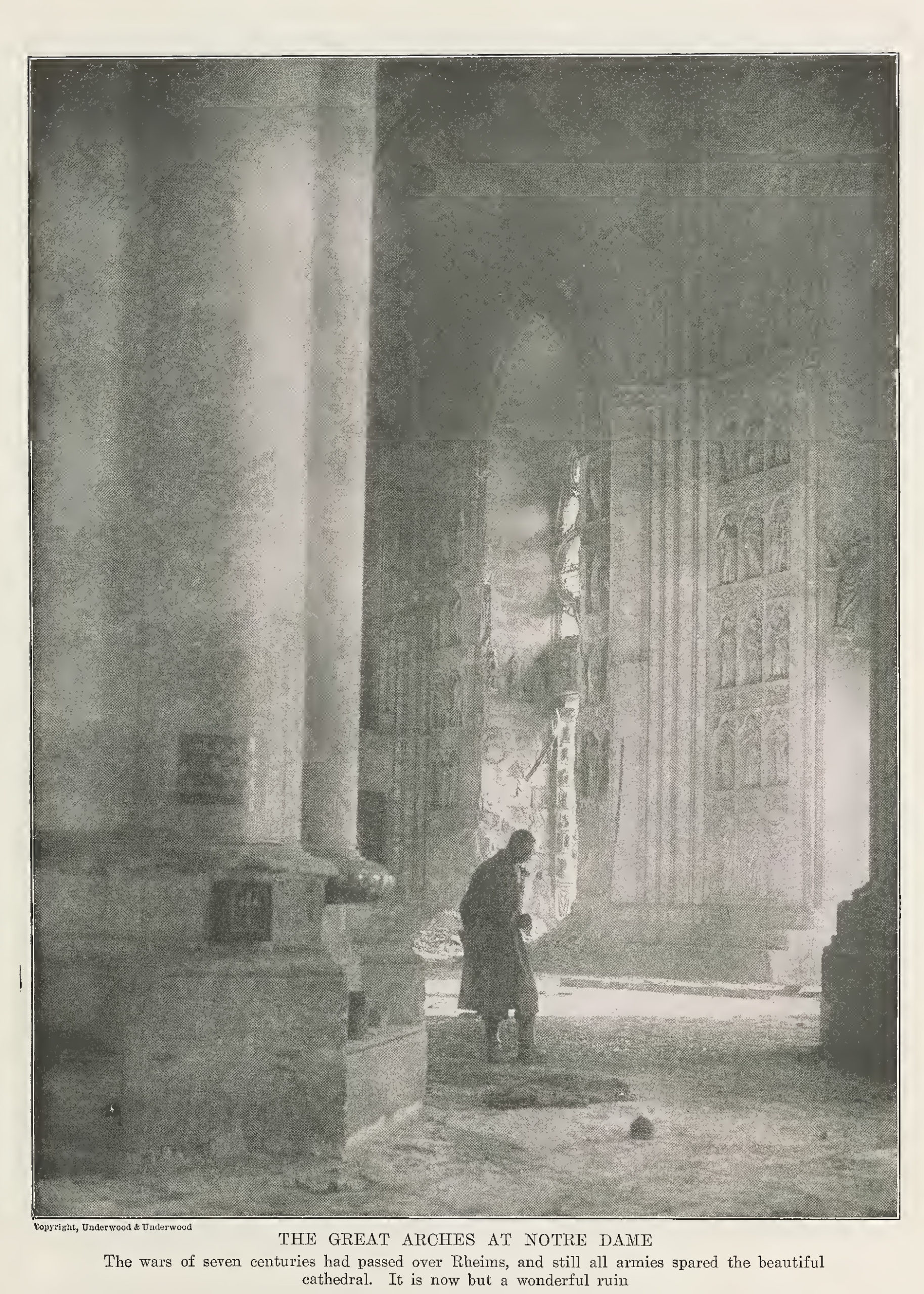

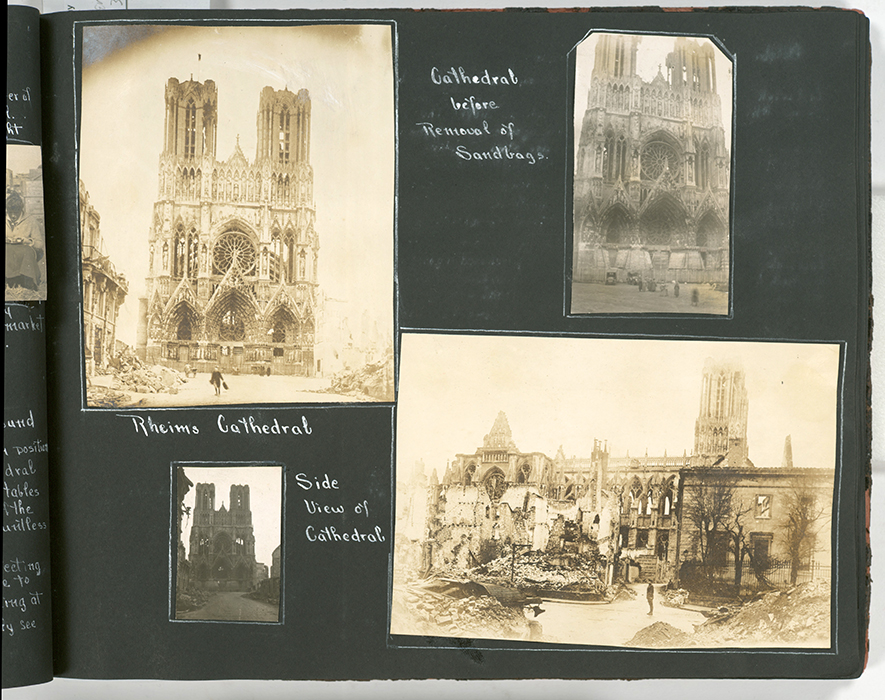

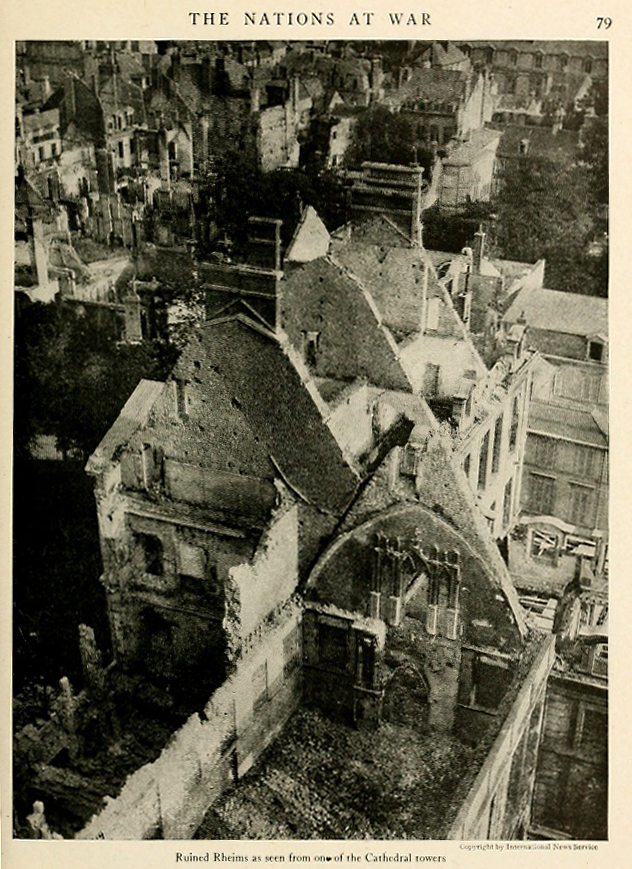

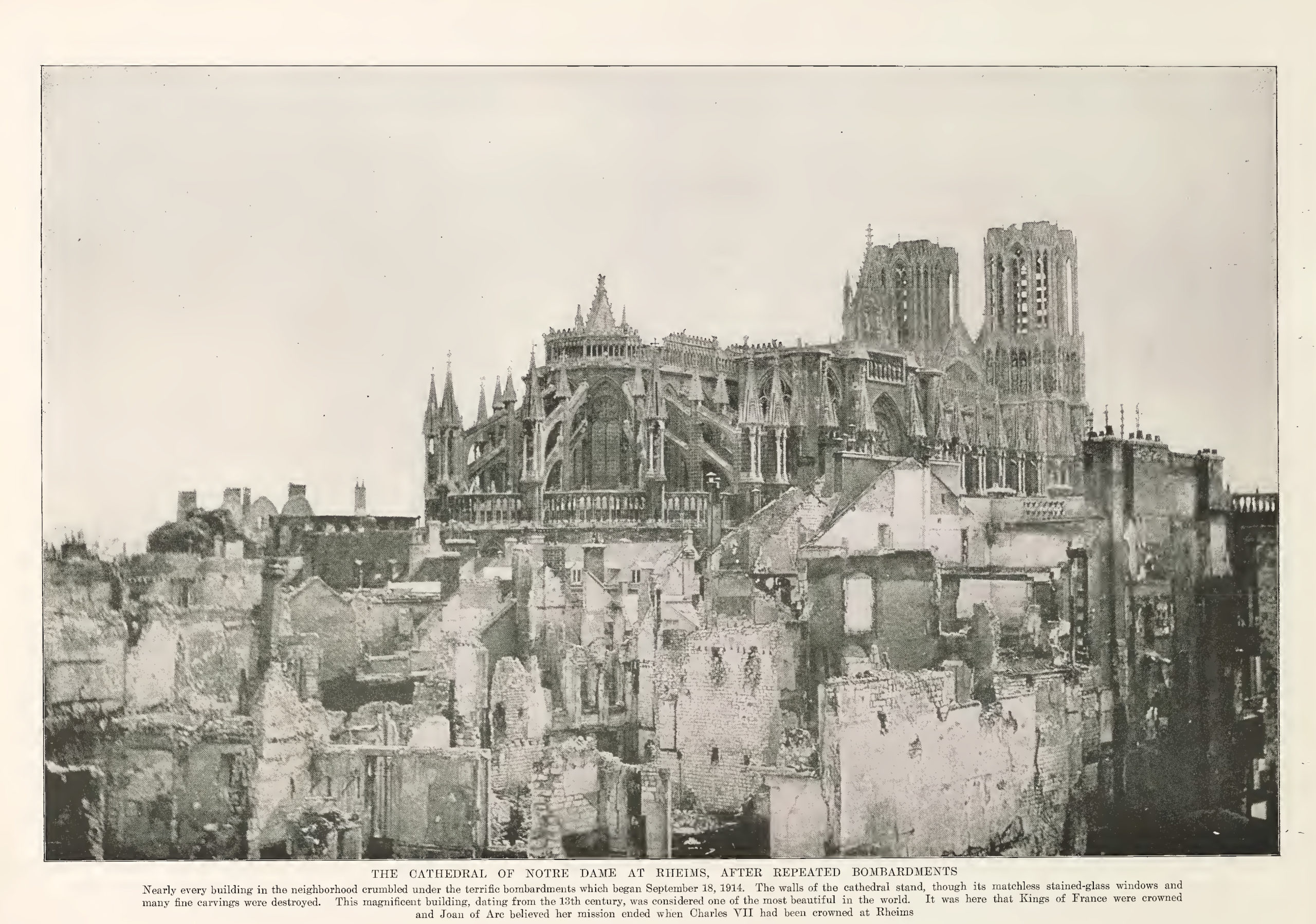

World War I officially started July 28, 1914. Originally it was believed that the “situation” would clear itself up by no later than Christmastime. Instead, it took over four long and grueling years, and resulted in more than 15 million deaths. Early on in the conflict, the German army moved into northeastern French territory. This was the beginning of the Western Front. The expeditious land grab by the Germans included the city of Reims. Reims had a well-established history, from its days as a bustling hub of the Roman Empire, to becoming a center of French culture in the early Middle Ages. Additionally, Reims was the “Coronation Capital,” so to speak, the traditional location for the coronation of French kings. It was also home to a magnificent high Gothic cathedral, Notre-Dame de Reims. By early September, the French had forced the Germans to retreat and though the French regained the town, the Germans stayed close by for the entirety of the war.

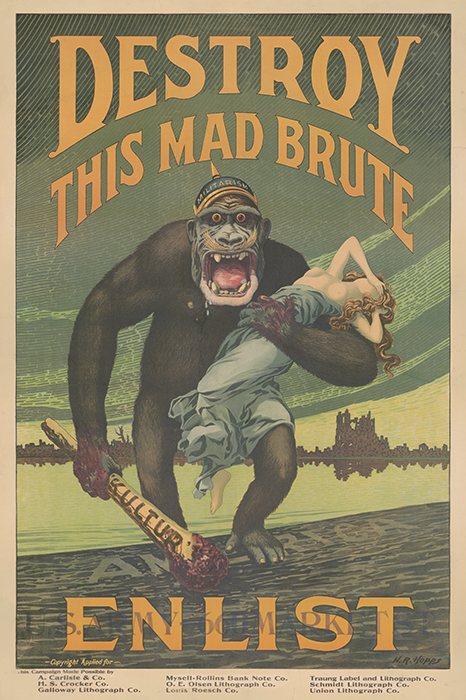

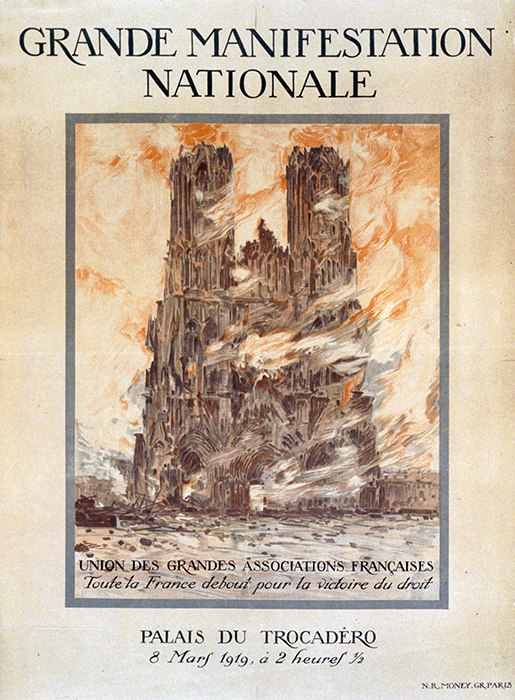

The city of Reims saw significant destruction, and both civilian and military casualties. But no event ignited indignation as did the bombing of the much-venerated Notre-Dame de Reims. The cathedral was first hit by shell fire on September 19th, 1914. Wooden scaffolding that was in place for ongoing repairs caught fire, and contributed to the damage, as did several smaller fires that resulted from the attack. Though the cathedral would be struck again and again as the war continued, it was this initial shelling that sparked a firestorm of outrage, horror, and prodigious propaganda—surely here was damning proof that the Germans were indeed “barbarians,” so lacking in culture themselves that they were compelled to destroy the beauty of another culture out of sheer spite and jealousy. The propaganda insisted that there was no reason to bomb the church since it had no strategic military value, and was a place of sanctuary. The French and their allies stressed that there was no justification to shell the cathedral especially given that was being used to house the wounded (mainly German soldiers callously left behind by their fleeing brothers-in-arms).

War crimes

It was acknowledged, even at the time, that the Germans were committing more horrendous acts than the bombardment of Reims Cathedral. So why should a building create more outcry and indignation than the killing of innocent civilians, or other kinds of wartime savagery? Perhaps it was in part that the cathedral, literally meaning the seat of the bishop, could be seen as representing the French nation as a whole, its cruciform shape evoking a sacrificial body. Or, on a more practical note, it was a story that could be easily sensationalized and discussed ad infinitum—cultural war damage was far easier to get past the censors. In the words of Maurice Landrieux, a former priest at Reims but later the Bishop of Dijon “…but it was the most ignoble, because it was at once sacrilegious and stupid, and because it reveals, by its uselessness, the blackest depth of German misdoing.” There was a pervasive belief that the Germans had come to France with the express intention of destroying the cathedral from the outset of the war.

There are two sides to every story, and so it is here. The Germans did shell the cathedral—that is irrefutable. Their explanation as to why they did so was wildly at odds with the French account, and they claimed to be horrified just as deeply as the French, at the damage done to this architectural masterpiece.

The French story was that is that the Germans, before their hasty retreat, had covered the floors of the cathedral with straw, to make it more combustible and that they intentionally left their wounded knowing they would be brought into the church by the French to be tended. A Red Cross flag was raised, a further signal that the cathedral was off-limits as a military target. However, the Germans later claimed the cathedral was being used for military intelligence: a signal station, telephone equipment, and an observation post had been espied in one of the towers during a German fly-by—along with a large cache of weapons. If true, according to international law, the cathedral was a viable military target—a wolf wrapped in sheep’s clothing.

The church was severely damaged—roofs had burned, statues melted, stonework was no longer viable, and more. Nonetheless, the structure was still essentially in good condition after the attack, all things considered. The local French authorities were actually taken to task by their own administrators for not doing a better job putting out the fire, which caused the majority of the damage. The Germans claimed it pained them to commit such an act, but the cunning French had left them no choice. These claims gained little traction.

The result was that—for the French—the German reputation for philosophical thought and general erudition, were suddenly erased—they were viewed once again as one of the “barbarian hordes” of the migration era. German art historians were quick to point out they had been one of the primogenitors of that discipline, and they highly appreciated art from around the globe. German art historians and professors were even dispatched to the front, joining various army units to help provide protection to valuable art on both sides, but to no avail. The mud would not unstick.

Culture wars

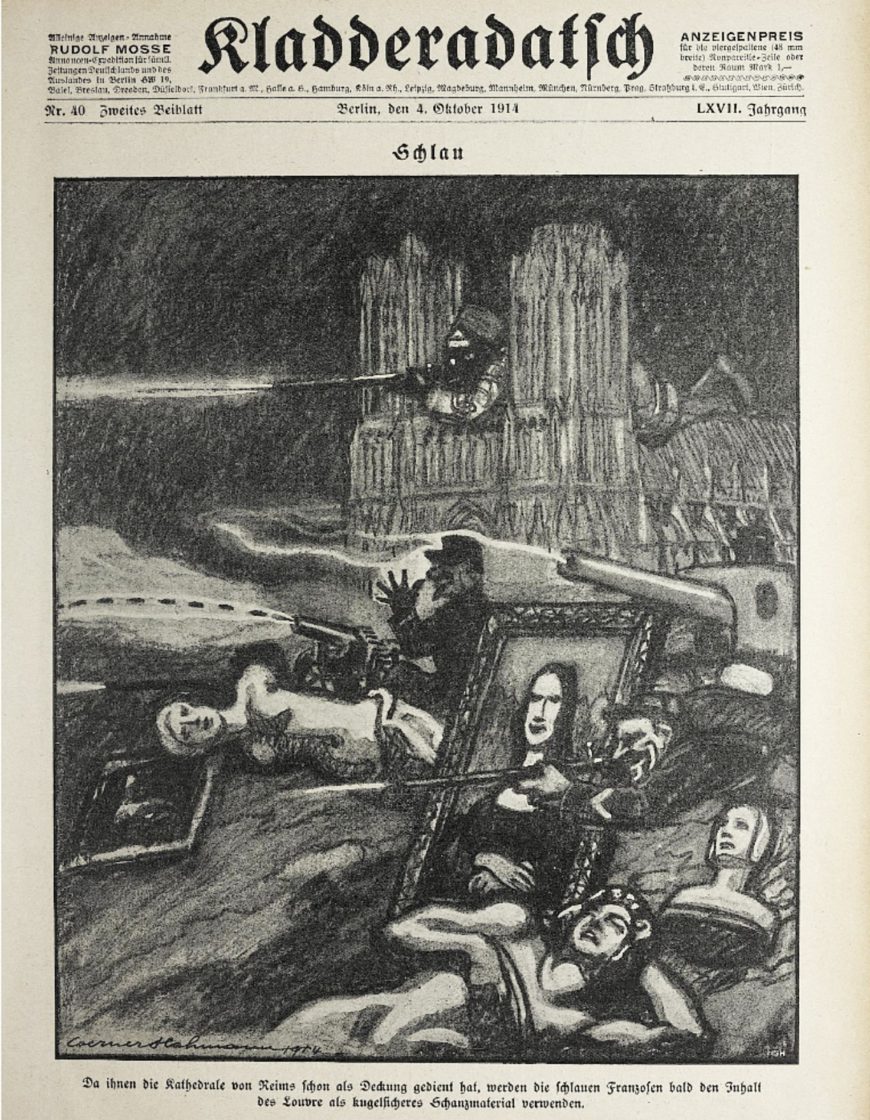

Reims Cathedral continued to be used as propaganda for the whole of the war. Its burnt image was printed on posters and postcards. German soldiers were depicted gun-wielding and slavering at the jaw to seeking to destroy the next great work of art they saw. Meanwhile, the Germans lampooned the French, accusing them of using their own great works of art for nefarious ends without compunction. One well-known cartoon read, “The cunning French have used Reims cathedral as a shooting platform—next they’ll be building trenches with the contents of the Louvre.”

Beyond the trenches, the battle for cultural superiority was on. The French had the upper hand when it came to the events at Reims that fateful night. They could claim eyewitnesses, and they also photographed the cathedral in ways intended to most incite a viewer.

The Germans did try hard though, despite their lack of handy visual evidence, to underscore that they had been the only country to carry out any form of art protection. Kunstschutz (the German term for the principle of preserving cultural heritage and artworks during armed conflict) was said to protect art on both sides of the war. It was even said to be endorsed by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself. The Germans emphasized that the bombing of the cathedral at Reims had not been part of a systematic effort, instead, it was one of the many sad byproducts of the war.

Neither side held back, each was determined to show that while one was on the side of the angels, the other was ruthlessly attempting to profit by the destruction of art. Meanwhile, the Germans claimed that as they were the creators of the Gothic style, and so the cathedral was just as much part of their cultural heritage as it was France’s, and they again attempted to remind the world of their integral role in the creation of art history. Again, this gained no traction with the French, nor with most nations.

By the end of the war Reims, which had been targeted multiple times, was the ruin the French had claimed after the initial attack. The continued attacks on the cathedral called into doubt the veracity of the Germans’ initial account. After the first bombardment, it was certain that the cathedral was no longer being used for any military purpose—if it ever had been. Again, a cultural landmark of this kind could only become subject to brute force with good reason, so the continued bombing only furthered the French position of German brutality and outright vandalism. J.W. Garner, in his International Law and the World War, states, “Monuments of this stature are not only entitled to respect because of their sanctity but are especially protected because of the Law of Nations” (p. 445).

Restoration on the cathedral began almost immediately after the end of the war, funded in part by the Rockefeller family. The cathedral reopened in 1938, though work continues to this day. Recently, the world looked on aghast when, in April of 2019, the iconic Notre-Dame de Paris burned. Even more recently, the lesser-known Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Nantes, another Gothic jewel, caught on fire. In these cases there appears to be no terrorism involved, only age and human error. Perhaps then, the. most important take-away from the bombing of Reims Cathedral is that blame is, to a degree, irrelevant, at least after the fact. The real lesson is that we must do better at preserving our cultural heritage the world over.