Because of the limits of nature, art objects are limited to the dimensions of space and time. For this reason, art objects fall into three categories: two-dimensional art, three-dimensional art, and four-dimensional art. Each category has divisions deriving primarily from differences between the materials and approaches used. Throughout history, art objects generally fit clearly into a discrete classification. In the nineteenth century, however, artists began exploring the limits of new materials as well as the boundaries of the categories into which they fell to see if they were real or arbitrary.

Figure 2.1 | Replication of Chauvet Cave Lion Wall. Author: User “HTO” Source: Wikimedia Commons License: Public Domain

2.3.1 Two-Dimensional Art

Two-dimensional art occurs on flat surfaces, like paper, canvas, or even cave walls. This art can be further divided into three main categories: drawing, painting, and printmaking. All art that occurs on a flat surface is one or a combination of these three activities.

2.3.1.1 Drawing

The term drawing describes both a visual object and an activity. At first glance, drawing appears to consist of making con- trasting marks on a flat surface. The term implies something more, however. One can “draw” water from a well or be “drawn” to a charismatic person. There is something in the word “draw” that is related to extracting or delineating, the “pulling out” of an essence. To draw an object is to observe its appearance and transfer that observation to a set of marks. Ancient cave painters truly “drew” the animals they saw around them based on their deep familiarity with their essential nature. (Figure 2.1) So in this context, drawing is a combination of observation and mark making.

Drawing is usually but not always done with monochromatic media, that is, with dry materials of a single color such as charcoal, conté crayon, metalpoint, or graphite. Color can be introduced using pastels. In addition to these dry materials, free-flowing ink can also be used to make drawings. These materials have been highly refined over centuries to serve specific artistic purposes.

Charcoal is made from wood or other organic material that has been burned in the absence of oxygen. This process leaves a relatively pure black carbon powder. Artists compress this dry powder, or pigment, with a binder, a sticky substance like pine resin or glue made from the collagen of animal hides, to make hand-held charcoal blocks of various strengths and degrees of hardness. This compressed charcoal is used to make very dark marks, usually on paper. Compressed charcoal is challenging to erase.

Figure 2.2 | Edmond Aman-Jean

Charcoal also comes in a form called willow or vine charcoal. This form of drawing charcoal leaves a very light mark as it is simply burned twigs. It is generally used for impermanent sketches because it does not readily stick to paper or canvas and is easily erased. Both compressed and vine charcoal drawings are easily smudged and should be protected by a fixative that adheres the charcoal to the drawing surface and creates a barrier resistant to smudging.

Conté crayon is a hand-held drawing material similar to compressed charcoal. Conté crayons are sticks of graphite or charcoal combined with wax or clay that come in a variety of colors, from white to sanguine (deep red) to black, as well as a range of hardness. Harder conté is used for details and softer varieties for broad areas. This portrait by Georges-Pierre Seurat (1859-1891, France) was drawn in black conté crayon on textured paper in order to break the image into discrete marks. (Figure 2.2)

Metalpoint is the use of malleable metals like silver, pewter, and gold to make drawing marks on prepared surfaces. (Figure 2.3) The surface must have a “tooth” or roughness to hold the marks. Any pure silver or gold object can be used for this, though artists today favor silver and gold wire held in mechanical pencils for the process.

Graphite is a crystalline form of carbon. In the sixteenth century, a large deposit of pure graphite was discovered in England, and it became the primary source for this drawing material. Because of its silvery color, it was originally thought to be a form of lead, though there is no actual lead in pencils. Today powdered graphite is mixed with clay to control hardness.

Pastels are similar to compressed charcoal but, instead of finely powdered carbon, finely ground colored pigment and a binder are used to create handheld colored blocks. (Figure 2.4) The powdery pigments smudge easily, so the image created must be displayed under glass or covered with a fixative. Edgar Degas (1834-1917, France) is famous for the subtle yet distinct layering of color he was able achieve in his pastel drawings. (Figure 2.5)

Oil pastels are semi-solid sticks of high pigment oil paint that are used like crayons. They were originally in- vented to mark livestock, but artists quickly realized their aesthetic potential. Oil pastels are a convenient way to apply and blend heavily textured oil-based pigment onto any surface without using traditional brushes. The colors are vibrant, and the marks are gestural and immediate so oil pastel drawings can show the “hand” of the artist in a direct way, as can be seen here in East Palatka Onions, a 1983 oil pastel drawing by Mary Ann Currier (b. 1927, USA). (East Palatka Onions, Mary Ann Currier: ketorg.cdn.ket.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/curri- er-ep-onions1100px.jpg)

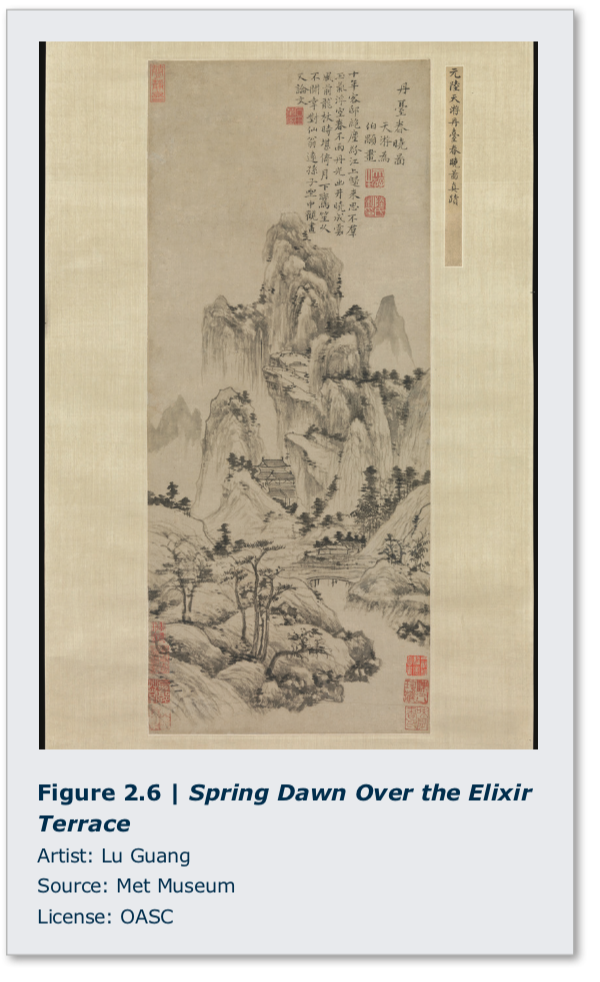

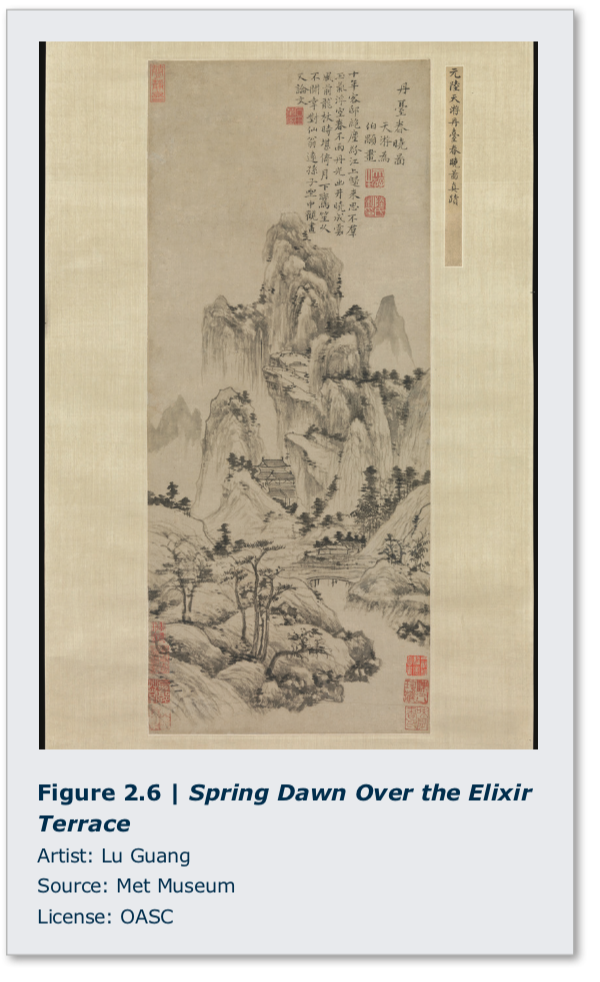

Ink is the combination of a colored pigment, usually black carbon or graphite, and a binder suspended in a liquid and applied with a pen or brush. A wide range of substances have been used over time to make ink, including lamp black or soot, burned animal bones, gall- nuts, and iron oxide. The pigment must be finely ground and held together with a binder. There is a long tradition of fine art ink drawings. Although the example given dates to the fourteenth century, the oldest ink drawings come from China in the third century BCE and are done on silk and paper. (Figure 2.6)

2.3.1.2 Painting

Painting is a specialized form of drawing that refers to using brushes to apply colored liquids to a support, usually canvas or paper, but sometimes wooden panels, metal plates, and walls. For example, Leonardo da Vinci painted Mona Lisa on a wood panel. (Figure 2.7) Paint is composed of three main ingredients: pigments, binders, and solvents. The colored pigments are suspended in a sticky binder in order to apply them and make them adhere to the support. Solvents dissolve the binder in order to remove it but can also be used in smaller quantities to make paint more fluid. As with drawing, different kinds of painting have mostly to do with the material that is being used. Oil, acrylic, watercolor, encaustic, fresco, and tempera are some of the different kinds of painting. For the most part, the pigments or coloring agents in paints remain the same. The thing that distinguishes one kind of painting from another is the binder.

Oil painting was discovered in the fifteenth century and uses vegetable oils, primarily linseed oil and walnut oil, as the binding agent. Linseed oil was chosen for its clear color and its ability to dry slowly and evenly. Turpentine is generally used as the solvent in oil painting. The medium has strict rules of application to avoid cracking or delamination (dividing into layers). Additionally, oil paint can oxidize and darken or yellow over time if not properly crafted. Some pigments have been found to be fugitive, meaning they lose their color over time, especially when exposed to direct sunlight. This can be seen in a detail of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa where the figure’s eyebrows and eye lashes are now “missing.” (Figure 2.8)

Acrylic painting is relatively modern and uses water-soluble acrylic polymer as the binding agent. Water is the solvent. Acrylic dries very quickly and can be used to build up thick layers of paint in a short time. One problem with acrylic is that the colors can subtly change as it dries, making this medium less suitable for portraiture or other projects where accurate color is vital. Nevertheless, acrylic paint is preferred over oil paint by many artists today, in part due to its greater ease of use and clean up, and because its rapid drying time allows the artist to work at a faster pace.

Watercolor painting suspends colored pigments in water-soluble gum arabic distilled from the Acacia tree as the binder. Watercolor paints are mixed with water and brushed onto an absorbent surface, usually paper. Before the industrial era, watercolor was used as an outdoor sketching medium because it was more portable than oil paint, which had to be prepared for use and could not be preserved for long periods or easily transported. (Figure 2.9) Today, however, many artists use watercolor as their primary medium.

Encaustic uses melted beeswax as the binder and must be applied to rigid supports like wood with heated brushes. The advantage of encaustic is that it remains fresh and vibrant over centuries. Encaustic paintings from ancient Egypt dating to the period of Roman occupation (late first century BCE-third century CE) are as brilliantly colored as when they were first painted. (Figure 2.10)

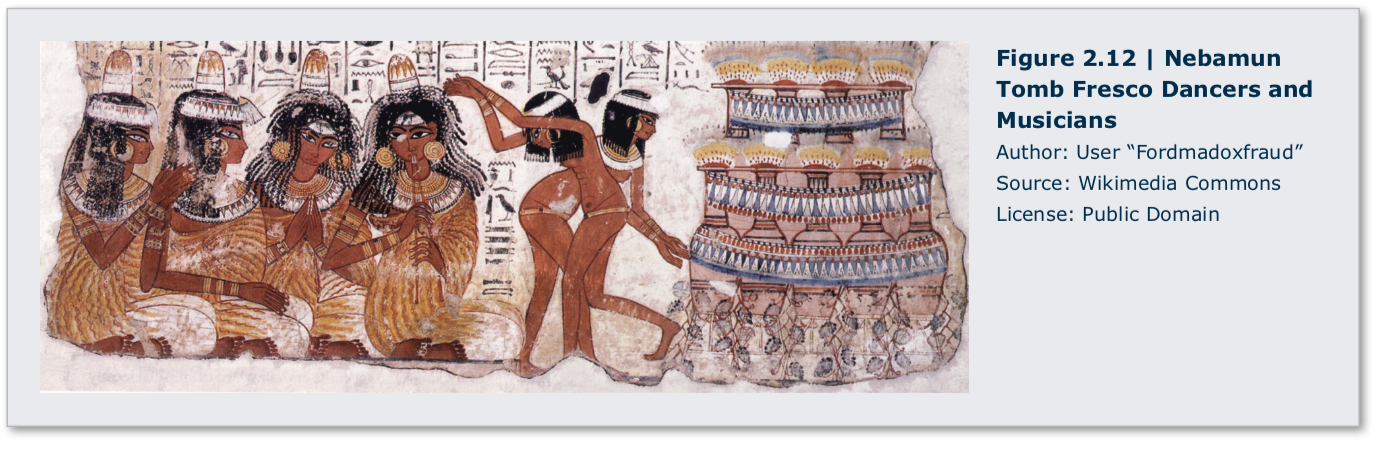

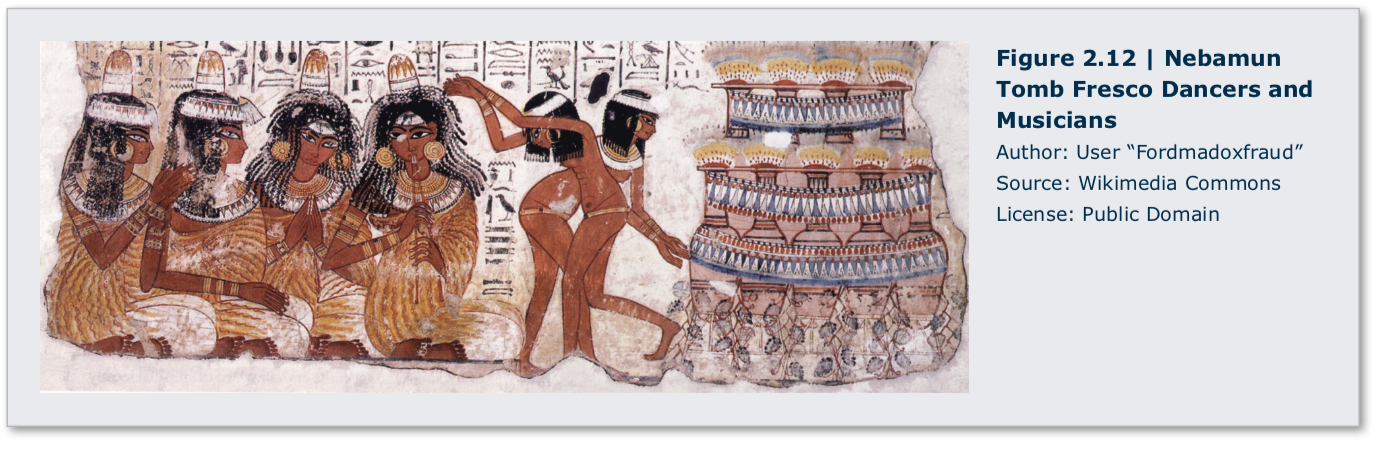

Fresco is the process of painting onto plaster; it is a long-lasting tech- nique. There are two kinds of fresco: buon fresco, or “good” fresco, is painting on wet plaster, and fresco secco, or dry fresco, is done after the plaster has dried. Paintings made using the buon fresco technique become part of the wall because the wet plaster absorbs the pigment as it is applied. (Figure 2.11) The only way to correct a buon fresco paint- ing is to chip it off the wall and start over. Buon fresco must be done in sections. Each section is called a giornate, which is Italian for “a day’s work.” Because it is done on dry plaster, fresco secco is more forgiving, but also less permanent as changes in moisture levels or damage to the wall can harm the painting. Due to the dry air and stable weather, there are fresco secco murals created as early as 3,000 BCE in ancient Egyptian tombs that remain largely intact. (Figure 2.12)

Tempera painting has been around for centuries. The most popular version of painting during the Middle Ages was egg tempera, in which dry colored pigments were mixed with egg yolk and applied quickly to a stable surface in layers of short brushstrokes. Egg tempera is a difficult medium to master because the egg yolk mixture dries very quickly, and mistakes cannot be corrected without damaging the surface of the painting. The Birth of Venus by San- dro Botticelli (1445-1510, Italy) is an egg tempera painting. (Figure 2.13)

2.3.1.3 Printmaking

A print is an image made by transferring pigment from a matrix to a final surface, often but not always paper. Printing allows multiple copies of an artwork to be made. Multiple copies of an individual art- work are called an edition.

There are four main types of printmaking: relief, intaglio, planographic, and stencil. Relief prints are made by removing material from the matrix, the surface the image has been carved into, which is often wood, linoleum, or metal. (Fig- ure 2.14) The remaining surface is covered with ink or pigment, and then paper is pressed onto the surface, picking up the ink. Letterpress is a relief printing process that transfers ink to paper but also indents an impression into the surface of the paper, creating a texture to the print that is often considered a sign of high quality.

Intaglio prints are made when a design is scratched into a matrix, usually a metal plate. Ink is wiped across the surface, and collects in the scratches. Excess ink is wiped off and paper is pressed onto the plate, picking up the ink from the scratches. Intaglio prints may also include texture.

Planographic prints are made by chemically altering a matrix to selectively accept or reject water. Originally, limestone was used for this process since it naturally repels water but can be chemically changed to absorb it. In stone matrix lithography, black grease pencil drawings are made on a flat block of limestone, which is then treated with nitric acid. (Figure 2.15) The nitric acid does not dissolve the stone, but changes it chemically so that it absorbs water. The grease pencil is removed, and the stone wet- ted. Where the grease pencil protected the stone from the acid, the limestone repels water and remains dry. Next, oil-based ink is rolled over the stone. Where the stone is dry, the ink will stick, but where the stone is wet, the ink will not. The image is “brought up” to the desired darkness by passing an ink covered roller on it, then it is printed by pressing paper onto the surfaceto pick up the ink. Most commercial printing today is lithographic printing, using aluminum plates instead of limestone blocks, or offset printing, where the inked image is transferred from a metal plate to a rubber cylinder and then to paper. (Figure 2.16)

Stencil prints are made by passing inks through a porous fine mesh matrix. In silkscreen printmaking, for example, silk fabric is mounted tightly on a rigid frame. Areas of the fabric are blocked off to form an image. The fabric-lined frame is placed on top of paper, canvas, or cloth. Ink is then pulled across the frame with a rubber blade. Where the fabric is blocked off, the ink does not transfer. Where the fabric is clear, ink is pushed through onto the receiving surface.

It is important to be able to distinguish between original prints and reproductions. Original prints are handmade prints. Since each print is subtly different due to its handmade character, each print is considered an original work of art. (Figure 2.17) Editions of original prints can range from a few to dozens or hundreds of copies. Reproductions are mechanically produced. An original artwork is photographed; the photograph is then transferred to a printing plate on a mechanical press. Each print is nearly identical, and editions can run into the thousands or tens ofthousands. (Figure 2.18)

The value of an individual print de- pends on a number of factors, includ- ing whether it is an original print or a reproduction and the number of prints in an edition. Recently a new kind of print has become popular, the gicleé.This is essentially a digital inkjet print. Those who buy gicleé prints should be careful that only acid-free paper and archival inks are used in its production. The fibers that make paper can come from many different sources, some of which contain acid that will turn the paper yellow with age. Over time, ink pigments can be fugitive, lose color intensity or even shift in hue. These effects will lower the value of the print. Acid-free paper and archival inks resist these defects and preserve the original appearance of the art object, thus maintaining its value.

2.3.2 Three-Dimensional Art

Three-dimensional art goes beyond the flat sur- face to encompass height, width, and depth. There are four main methods used in producing art in three dimensions. All three-dimensional art uses one or a combina- tion of these four methods: carving, modeling, casting, or assembly. A form of three-dimensional art that emerged in the twentieth century is installation, a work in which the viewer is surrounded within a space or moves through a space that has been modified by the artist.

Sculpture can be either freestanding—“in the round”—or it can be relief—sculpture that projects from a background surface. There are two categories of relief sculpture: low relief and high relief. In low relief, the amount of projection from the background surface is limited. A good example of low relief sculpture would be coins, such as these ancient Roman types dating from c. 300 BCE to c. 400 CE. (Figure 2.19) Also, much Egyptian wall art is low relief. (Figure 2.20) High relief sculpture is when more than half of the sculpted form projects from the background surface. This method generally creates an effect called undercut, in which some of the projected surface is separate from the background surface. Mythological scenes depicted on the Parthenon, an ancient Greek temple, (Figure 2.21) and the Corporate Wars series (Corporate Wars, Robert Longo: media.mutualart.com/Images/2 009_07/24/0205/582184/49777ffa-d61f-42aa- a3f1-9c47ed564b05_g.Jpeg) by Robert Longo (b. 1953, USA) are both examples of high relief using undercut.

Sculpture can be either freestanding—“in the round”—or it can be relief—sculpture that projects from a background surface. There are two categories of relief sculpture: low relief and high relief. In low relief, the amount of projection from the background surface is limited. A good example of low relief sculpture would be coins, such as these ancient Roman types dating from c. 300 BCE to c. 400 CE. (Figure 2.19) Also, much Egyptian wall art is low relief. (Figure 2.20) High relief sculpture is when more than half of the sculpted form projects from the background surface. This method generally creates an effect called undercut, in which some of the projected surface is separate from the background surface. Mythological scenes depicted on the Parthenon, an ancient Greek temple, (Figure 2.21) and the Corporate Wars series (Corporate Wars, Robert Longo: media.mutualart.com/Images/2 009_07/24/0205/582184/49777ffa-d61f-42aa- a3f1-9c47ed564b05_g.Jpeg) by Robert Longo (b. 1953, USA) are both examples of high relief using undercut.

Modeling is an additive process in which easily shaped materials like clay or plaster are built up to create a final form. Some modeled forms begin with an armature, or rigid inner support often made of wire. An ar- mature allows a soft or fluid material like wet clay, which would collapse under its own weight, to be built up. This method of sculpting includes most classical portrait sculpture in terra cotta, or baked clay. (Figure 2.22) Clay lends itself to modeling and is thus a popular medium for work of this kind, although clay may also be carved and cast.

Modeling is an additive process in which easily shaped materials like clay or plaster are built up to create a final form. Some modeled forms begin with an armature, or rigid inner support often made of wire. An ar- mature allows a soft or fluid material like wet clay, which would collapse under its own weight, to be built up. This method of sculpting includes most classical portrait sculpture in terra cotta, or baked clay. (Figure 2.22) Clay lends itself to modeling and is thus a popular medium for work of this kind, although clay may also be carved and cast.

Carving is the removal of material to form an art object. Carving is a subtractive process that usually begins with a block of material, most commonly stone. Tools—usually metal or metal tipped— are used to chip away the stone until the final form emerges. (Figure 2.23) The main concern in carving, aside from achieving the correct form, is to be careful not to chip away too much material, as it cannot be replaced once it has been removed. (Figure 2.24) It is possible that the final shape of some carved stone sculptures result from not only the artist’s intention, but also the subtle shifts caused by unpredictable variations in the stone causing the artist to “change course” when too much stone came away. This possibility is not to suggest that trained sculptors do not know the limits of their medium: artists often encounter surprises and innovative ones can sometimes work solutions that incorporate them.

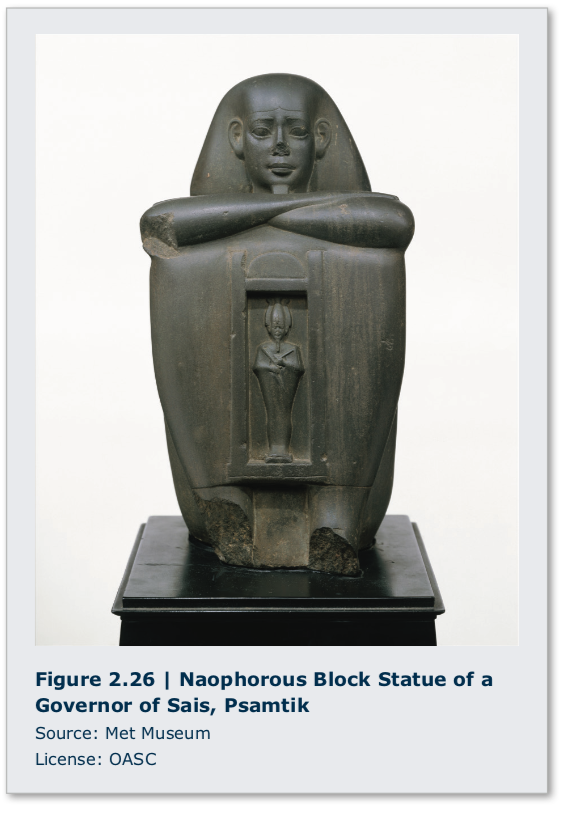

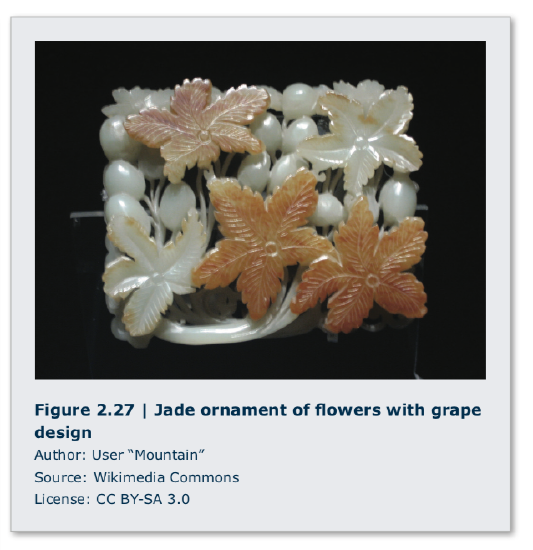

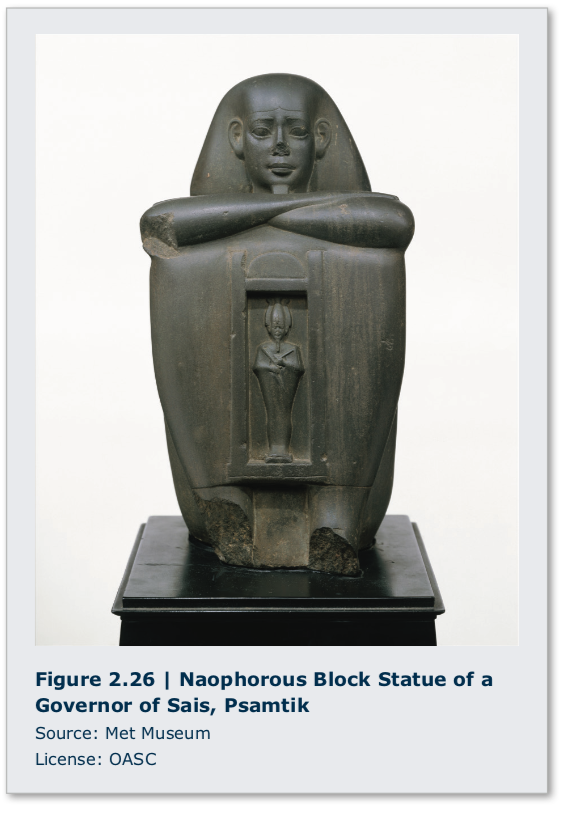

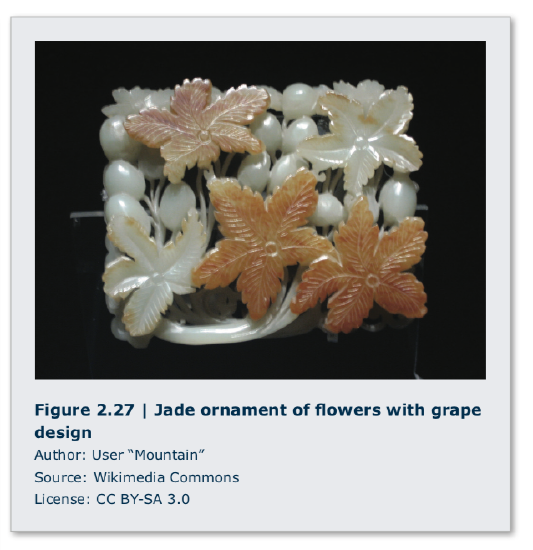

Different kinds of stone vary in hardness as well as color and appearance. Not all stone is suit- able for sculpting. Marble, a form of limestone, was preferred by the ancient Greeks and Romans for its softness and even color. (Figure 2.25) Diorite, schist (a form of slate), and Greywacke (a form of granite) were preferred by Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures for their hardness and permanence. (Figure 2.26) The Chinese have traditionally used jade, a hard, brittle stone found in numerous shades, most commonly green, to indicate wisdom, power, and wealth. (Figure 2.27)

Wood is also often used as a carving material. Because of variations in grain size and texture, different species of wood have different sculptural qualities. In general, wood is prized for its flexibility and ease of forming, though it reacts to changes in humidity and lacks permanence. During the Heian era (794-1185 CE), the Japanese artist Jocho used joined wood to construct his sculpture of the Seated Buddha. (Figure 2.28)

Casting is a process that replaces, or substitutes, an initial sculptural material such as wax or clay with another, usually more permanent, material such as bronze, an alloy, or mixture of copper and tin. Casting is also a process that makes it possible to create multiple versions of the same object.

In the lost wax process, an original sculpture is modeled, often in clay, coated in wax, and then covered in plaster to create a mold. When the plaster dries, it is heated to melt the wax, which is poured out of the mold. Molten metal is then poured into the space within the mold between the (now lost) wax coating and the original sculpted form. When the metal has cooled and solidified, the plaster is broken away to reveal the cast metal object. (Figure 2.29) In order to create multiple versions of the object, the mold must be made in such a way that it can be re- moved without being destroyed. (Figure 2.30) This operation is generally achieved by separating a mold into several sections while the original is being cast. Sectional molds are also used to cast original objects that cannot be melted or otherwise removed from the mold. To cast the form, the original is removed, and the sections are then re-fastened together. In some cases, complex sculptures are cast in several pieces and the resulting metal sections are welded together.

In the lost wax process, an original sculpture is modeled, often in clay, coated in wax, and then covered in plaster to create a mold. When the plaster dries, it is heated to melt the wax, which is poured out of the mold. Molten metal is then poured into the space within the mold between the (now lost) wax coating and the original sculpted form. When the metal has cooled and solidified, the plaster is broken away to reveal the cast metal object. (Figure 2.29) In order to create multiple versions of the object, the mold must be made in such a way that it can be re- moved without being destroyed. (Figure 2.30) This operation is generally achieved by separating a mold into several sections while the original is being cast. Sectional molds are also used to cast original objects that cannot be melted or otherwise removed from the mold. To cast the form, the original is removed, and the sections are then re-fastened together. In some cases, complex sculptures are cast in several pieces and the resulting metal sections are welded together.

Assembly, or assemblage, is a fairly recent type of sculpture. Before the modern period, carving, casting, and modeling were the only accepted methods of making fine art sculpture. Recently, sculptors have enlarged their approach and turned to the process of assembly, manually attaching objects and materials together. Assemblies are often composed of mixed media, a process in which disparate objects and substances are used in order to achieve the desired effect.

Because she spent time near a cabinetry workshop, Louise Nevelson (1899-1988, Ukraine, lived USA) would retrieve wooden cut-offs and other discarded objects to use in her sculpture. Her art practice involved the use of found objects. Consider Nevelson’s Sky Cathedral. (Sky Cathedral, Louise Nevelson: http://www.moma.org/collection/works/81006) She filled individual wooden boxes with found objects. She then arranged these boxes into large assemblies and painted them a single color, usually black or white. Each sub-unit box in the sculpture can be read as a separate point of view or separate world. The effect of the whole is to recognize that both unity and diversity are possible in a single artwork.

Installation is related to assembly, but the intent is to transform an interior or exterior space to create an experience that surrounds and involves the viewer in an unscripted interaction with the environment. The viewer is then immersed in the art, rather than experiencing the art from a distance. For example, Carsten Höller (b. 1961, Belgium, lives Sweden) installed Test Site in the Turbine Hall, a five-story open space, at the Tate Modern in London. (Figure 2.31) Part of a series of slides Höller created at museums worldwide, he wanted to encourage visitors to use the practical, though unconventional, means of transport, and, while doing so, to experience the momentary loss of control and whatever emotional response each individual felt.

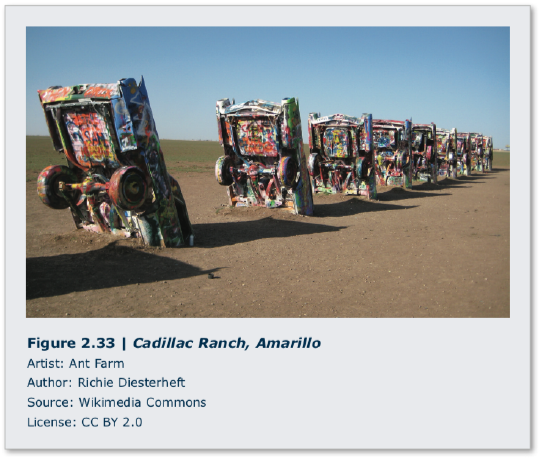

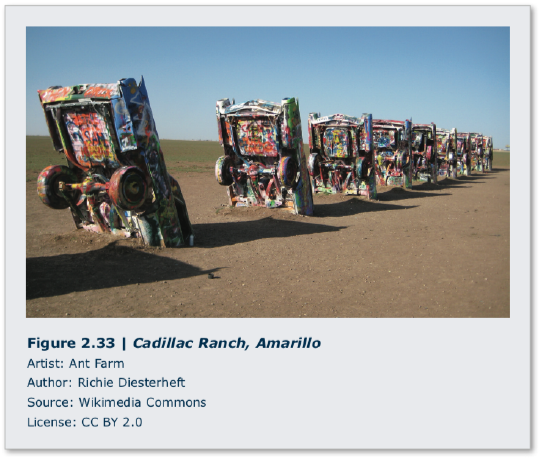

An installation that is intended for a particular location is called a site-specific installation. Good examples of site-specific installations would be Tilted Arc by Richard Serra (b. 1939, USA), (Tilted Arc, Richard Serra: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/ File:Tilted_arc_en.jpg); Lightning Field by Walter De Maria (1935-2013, USA), (Lightning Field, Walter de Maria: sculpture1.wikispaces. com/file/view/Walter_de_Maria_Lightning_ Field_1977.jpg/310921734/800x686/Walter_de_ Maria_Lightning_Field_1977.jpg); Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson (1938-1973, USA), (Figure 2.32); and Cadillac Ranch by the art group known as Ant Farm. (Figure 2.33) In part because of the large scale of many of these works, installation is an increasingly popular form of public artwork.

An installation that is intended for a particular location is called a site-specific installation. Good examples of site-specific installations would be Tilted Arc by Richard Serra (b. 1939, USA), (Tilted Arc, Richard Serra: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/ File:Tilted_arc_en.jpg); Lightning Field by Walter De Maria (1935-2013, USA), (Lightning Field, Walter de Maria: sculpture1.wikispaces. com/file/view/Walter_de_Maria_Lightning_ Field_1977.jpg/310921734/800x686/Walter_de_ Maria_Lightning_Field_1977.jpg); Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson (1938-1973, USA), (Figure 2.32); and Cadillac Ranch by the art group known as Ant Farm. (Figure 2.33) In part because of the large scale of many of these works, installation is an increasingly popular form of public artwork.

Kinetic art is art that moves or appears to move. Generally this art is sculptural. Good examples of kinetic artworks are the suspended, freely moving mobiles of Alexander Calder (1898-1976, USA) that are meant to change shape as part of their design. (Nénuphars Rouges, Alexander Calder: http://www.wikiart.org/en/alexander-calder/ red-lily-pads-n-nuphars-rouges-1956?utm_source=returned&utm_medium=referral&utm_ campaign=referral) Homage to New York was a work of kinetic art Jean Tinguely (1925-1991, Switzerland) intended to self-destruct, although it never completed its purpose because a local fire department stepped in and stopped the process. (Homage to New York, Jean Tinguely: http://www.wikiart.org/en/jean-tingu...-new-york-1960) Reuben Margolin (USA) is a contemporary artist who uses intersecting waves to create beautifully undulating sculptures. Click the following link to view a video of Margolin’s Square Wave: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4UQtDbybSWc. Beginning with simple materials like paper towel tubes, fishing swivels, and fishing line, and then moving to larger, more complex sculptures using more permanent materials like wood, metal, and wire, Margolin has made a career of creating meditatively flowing sculptures.

2.3.3 Four-Dimensional Art

Four-dimensional art, or time-based art is a relatively new mode of art practice that includes video, projection mapping, performance, and new media art.

Video art uses the relatively new technology of projected moving images. These images can be displayed on electronic monitors or projected onto walls or even buildings; they use light as a medium. The early video constructions of Nam June Paik (1932-2006, South Korea, lived USA) are a good example. In TV Cello, video monitors are assembled in the shape of a cello. (TV Cello, Nam June Paik: http://a141.idata.over-blog.com/356x....-TV-Cello.jpg) When a bow was drawn across this object, images of a woman playing a cello appeared on the screens.

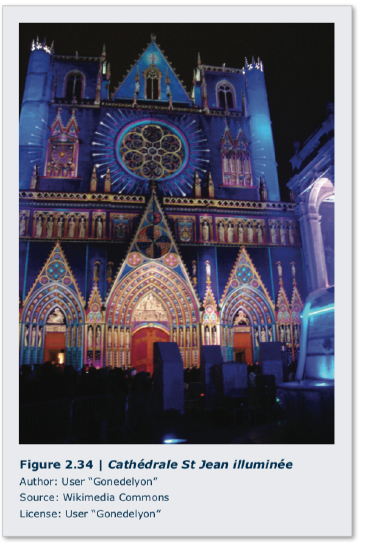

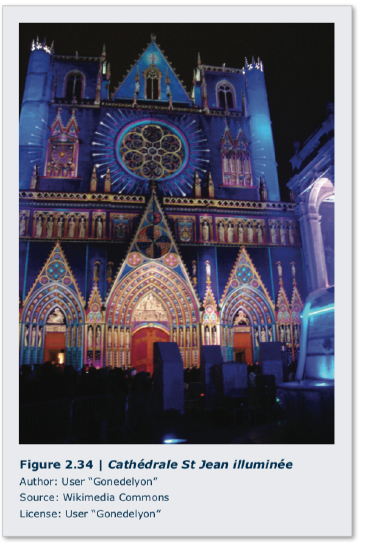

Projection mapping is another use of video projection. One or more two or three-dimensional objects (often buildings) are spatially mapped into a virtual program that then allows the image to conform to the surface of the object upon which it is projected. (Figure 2.34) Evan Roth (b. 1978, USA, lives France) creates graffiti as a video projection and then photographs the results; thus, the work is temporary. This method of spatially augmented reality has been used by numerous artists (and advertisers) to “tag” everything from public spaces to the human face, without leaving permanent marks.

Performance art is art in which the artist’s medium is an action. Performance artworks are generally documented by photography, but the artwork is in the act itself. Cut Piece is a performance work Yoko Ono (b. 1933, Japan, lives USA) originally created in 1964 in which audience members were given scissors to cut off pieces of her clothing while the artist sat on a stage. (Cut Piece, Yoko Ono: en.Wikipedia. org/wiki/File:CutPieceOno.jpeg) As the artist passively allowed her garments to fall away, the participants and viewers were in control of her transformation from whole to segmented.

New media art usually refers to interactive works such as digital art, computer animation, video games, robotics, and 3D printing, where artists explore the expressive potential of these new creative technologies. The international connectivity of the Internet has ushered in a globalization of information exchange which includes the arts. One example of the use of new media in art would be 10,000 Moving Cities by Marc Lee (b. 1969, Switzerland). In this work, a viewer wears a video projection headset in which images from a chosen city are projected onto a digital urban architecture. The viewer can move within the new space through head motion. Real time social media images and text from the chosen city are also captured and projected.

Modeling is an additive process in which easily shaped materials like clay or plaster are built up to create a final form. Some modeled forms begin with an armature, or rigid inner support often made of wire. An ar- mature allows a soft or fluid material like wet clay, which would collapse under its own weight, to be built up. This method of sculpting includes most classical portrait sculpture in terra cotta, or baked clay. (Figure 2.22) Clay lends itself to modeling and is thus a popular medium for work of this kind, although clay may also be carved and cast.

Modeling is an additive process in which easily shaped materials like clay or plaster are built up to create a final form. Some modeled forms begin with an armature, or rigid inner support often made of wire. An ar- mature allows a soft or fluid material like wet clay, which would collapse under its own weight, to be built up. This method of sculpting includes most classical portrait sculpture in terra cotta, or baked clay. (Figure 2.22) Clay lends itself to modeling and is thus a popular medium for work of this kind, although clay may also be carved and cast.

In the lost wax process, an original sculpture is modeled, often in clay, coated in wax, and then covered in plaster to create a mold. When the plaster dries, it is heated to melt the wax, which is poured out of the mold. Molten metal is then poured into the space within the mold between the (now lost) wax coating and the original sculpted form. When the metal has cooled and solidified, the plaster is broken away to reveal the cast metal object. (Figure 2.29) In order to create multiple versions of the object, the mold must be made in such a way that it can be re- moved without being destroyed. (Figure 2.30) This operation is generally achieved by separating a mold into several sections while the original is being cast. Sectional molds are also used to cast original objects that cannot be melted or otherwise removed from the mold. To cast the form, the original is removed, and the sections are then re-fastened together. In some cases, complex sculptures are cast in several pieces and the resulting metal sections are welded together.

In the lost wax process, an original sculpture is modeled, often in clay, coated in wax, and then covered in plaster to create a mold. When the plaster dries, it is heated to melt the wax, which is poured out of the mold. Molten metal is then poured into the space within the mold between the (now lost) wax coating and the original sculpted form. When the metal has cooled and solidified, the plaster is broken away to reveal the cast metal object. (Figure 2.29) In order to create multiple versions of the object, the mold must be made in such a way that it can be re- moved without being destroyed. (Figure 2.30) This operation is generally achieved by separating a mold into several sections while the original is being cast. Sectional molds are also used to cast original objects that cannot be melted or otherwise removed from the mold. To cast the form, the original is removed, and the sections are then re-fastened together. In some cases, complex sculptures are cast in several pieces and the resulting metal sections are welded together.

An installation that is intended for a particular location is called a site-specific installation. Good examples of site-specific installations would be Tilted Arc by Richard Serra (b. 1939, USA), (Tilted Arc, Richard Serra:

An installation that is intended for a particular location is called a site-specific installation. Good examples of site-specific installations would be Tilted Arc by Richard Serra (b. 1939, USA), (Tilted Arc, Richard Serra: