6.1: Modern to Postmodern

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 245128

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between the categories of late Modernism and post Modernism in art.

Key Points

- The predominant term for art produced since the 1950s is Contemporary Art. The terminology often points to similarities between late Modernism and Postmodernism, although there are differences.

- Modern art, radical movements in Modernism, and radical trends regarded as influential and potentially as precursors to late Modernism and Postmodernism emerged around World War I and particularly in its aftermath.

- The discourse that encompasses the two terms Late Modernism and Postmodern art is used to denote what may be considered as the ultimate phase of modern art, as art at the end of Modernism or as certain tendencies of contemporary art.

- Late Modernism describes movements which arise from and react against trends in Modernism and rejects some aspect of Modernism, while fully developing the conceptual potentiality of the modernist enterprise.

Key Points

- precursors: That which precedes; a forerunner; a predecessor; an indicator of approaching events.

Background

The predominant term for art produced since the 1950s is Contemporary Art, although more specifically it might be used to refer to art created within a decade of the current moment. Not all art labeled ‘contemporary’ is modern or postmodern, and the term contemporary encompasses both artists who continue to work in modernist or late modernist traditions, as well as artists who reject Modernism for Postmodernism or other reasons. Arthur Danto argues explicitly in After the End of Art that contemporaneity is the broader term, and that postmodern objects represent a sub-sector of the contemporary movement which replaced modernity and Modernism.

Radical movements in modern art

Modern art, radical movements in Modernism, and radical trends regarded as influential and potential precursors to late Modernism and Postmodernism emerged around World War I and particularly in its aftermath. With the introduction of the use of industrial artifacts in art came movements such as Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism as well as techniques such as collage and art forms such as cinema and the rise of reproduction as a means of creating artworks. Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and many others created important and influential works from found objects. There was about Modernism also a kind of implicit idea of the forward and inevitable movement of human culture. WWI and especially WWII disrupted this idea and made the Modern moment more problematic.

Late Modernism vs. Postmodernism

The discourse surrounding the terms Late Modernism and Postmodern art is fraught with many differing opinions. There are those who argue against any division into Modern and Post-Modern periods. Some don’t believe that the period called Modernism is over or even near the end, and there certainly is no agreement that all art after Modernism is Post-Modern, nor that Post- Modern art is universally separated from Modernism; many critics see it as merely another phase in Modern art or another form of late Modernism. There is, however, a consensus that a profound change in the perception of works of art, and works of art themselves, has occurred and that a new era has been emerging on the world stage since at least the 1960s.

Late Modernism describes movements which arose from and react against trends in Modernism, rejecting some aspect of Modernism, while fully developing the conceptual potentiality of the modernist enterprise. In some descriptions Postmodernism as a period in art history is completed, whereas in others it is a continuing movement in Contemporary art. In art, the specific traits of Modernism which are cited generally consist of: formal purity, medium specificity, art for art’s sake, the possibility of authenticity in art, the importance or even possibility of universal truth in art, and the importance of an avant-garde and originality. This last point is one of particular controversy in art, where many institutions argue that being visionary, forward-looking, cutting edge, and progressive are crucial to the mission of art in the present, and that postmodern art therefore represents a contradiction of the value of art of our times.

One compact definition of Postmodernism is that it rejects Modernism’s grand narratives of artistic direction, eradicates the boundaries between high and low forms of art, disrupts the genre and its conventions with collision, collage, pastiche, and fragmentation. Postmodern art comes from the viewpoint that all stances are unstable and insincere, and therefore irony, parody, and humor are the only positions which cannot be overturned by critique or later events.

Rauschenberg and Johns

Both men fought in WWII and used the Post-War G.I. Bill to study art. They met at the Black Mountain art school in North Carolina being run at that time by Josef and Annie Albers.

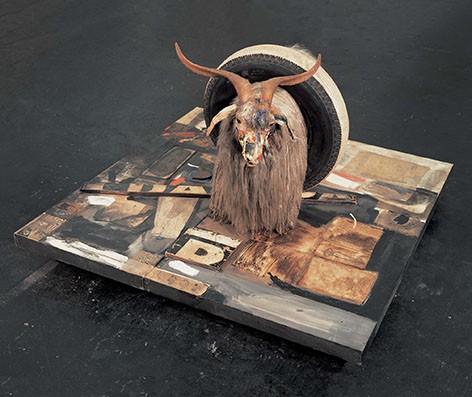

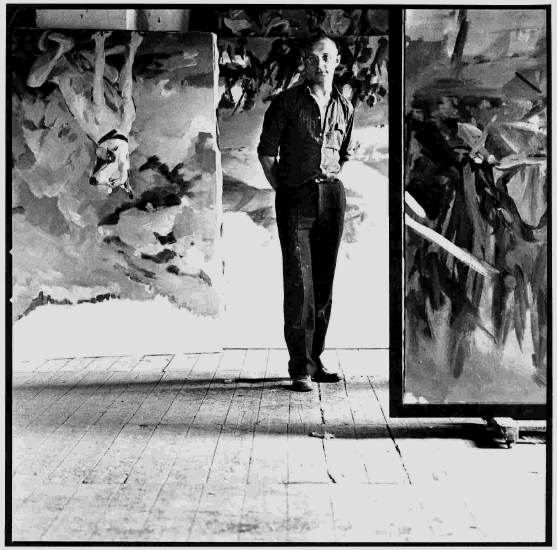

Eventually they became a couple and moved to New York City into two lofts in the same downtown building. Rauschenberg was already creating avant-garde art like his “all whites”, or canvases painted in that single color. Many elements of the art might be seen in contrast to the preeminent movement of the day, Abstract Expressionism. The Combines of Rauschenberg which combined paint with found objects and other materials took Duchamp’s Readymades one step further.

Johns used encaustic paint (pigment in hot wax), often over newsprint to mimic the brushwork of the Abstract Expressionists without the actual hand of the artist being involved. This ironic remove suggests the issues addressed by Post-Modern artists in the decades to come.

While their partnership was relatively short-lived, Rauschenberg and Johns inspired each other in a conversation that took Modern art in America to a new and unique place.

Happenings

Alan Kaprow was the major innovator behind the performances called Happenings in the 1950’s and 60’s. He studied at Columbia University with Meyer Shapiro, but also at the New School with John Cage whose experiments in “chance operations” and other ideas coming rom Cage’s interest in Zen Buddhism were influential. Happenings were often a kind of street theater, although not all took place in the street, and involved a sometimes invited, sometimes ad hoc audience who would interact with whatever was going on. These often highly scripted events would become part of the environment that would become true Conceptual art. Both Happenings and Pop Art began to remove art from the rarified elite world of museums and galleries and insist on work that engaged with the contemporary world as it was. This disruptive and revolutionary mind-set was also part of the zeitgeist in America following the country’s entrance into the Vietnam conflict. Revolution was in the air and artists were making work that was very much of the time.

Pop Art

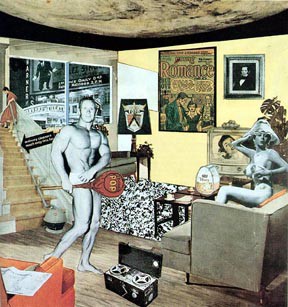

Possibly the most popular form of American art is art that takes its name from that word – popular. Popular culture became the subject matter of much of the work made in the 50s and 60s. As we have seen, after WWII, American culture was in the ascendant and in England American G.I.’s brought magazines, records, and other elements of everyday life with them. Richard Hamilton was in art school at that time and found the images from America with its suggestion of consumer abundance fascinating.

In American, Andy Warhol was making paintings of subjects like water heaters taken from newspaper ads. He disliked the technique of painting which he has said was too personal. When he was introduced to silkscreen printing he began to make art using that technique with all of its deletion of the hand of the artist and incorporation of chance operations – registration could create large differences between canvases.

Conceptual Art

Conceptual art is defined by concepts or ideas taking precedence over traditional aesthetic and material concerns.

Key Points

- Conceptual art emerged as a movement during the 1960s. In part, it was a reaction against formalism articulated by the influential New York art critic Clement Greenberg.

- Some have argued that conceptual art continued this dematerialization of art by removing the need for objects altogether, while others, including many of the artists themselves, saw conceptual art as a radical break with Greenberg’s formalist Modernism.

- French artist Marcel Duchamp paved the way for the conceptualists, providing examples of prototypically conceptual works such as his ready-mades.

- Conceptual artists began a far more radical interrogation of art than was previously possible. One of the first and most important things they questioned was the common assumption that the role of the artist was to create special kinds of material objects.

- The notion that art should examine its own nature was already a potent aspect of the influential art critic Clement Greenberg’s vision of modern art during the 1950s.

Key Terms

- conceptualist: An artist involved in the conceptualism movement.

- dematerialization: The act or process of dematerializing.

Formalism, Dematerialization and the Commodification of Art

Conceptual art is defined by the concepts of a work taking precedence over the traditional aesthetic and material concerns. It began to emerge as a movement during the 1960s, in part as a reaction against formalism as then articulated by the influential New York art critic Clement Greenberg. According to Greenberg, modern art followed a process of progressive reduction and refinement toward the goal of defining the essential, formal nature of each medium. The task of painting, for example, was to define precisely what kind of object a painting truly is: what makes it a painting and nothing else. For example, if the nature of paintings is as flat canvas objects onto which colored pigment is applied, elements such as figuration, 3-D perspective illusion, and references to external subject matter were extraneous to the essence of painting and should thus be removed.

Some have argued that conceptual art continued this dematerialization of art by removing the need for objects altogether while others, including many of the artists themselves, saw conceptual art as a radical break with Greenberg’s formalist Modernism. Later artists continued to share a preference for art to be self-critical and a distaste for illusion. However, by the end of the 1960s it was clear that Greenberg’s stipulations for art to continue within the confines of each medium and exclude external subject matter no longer held traction. Lucy Lippard, an internationally known writer, art critic, activist and curator from the United States, was among the first writers to recognize the dematerialization at work in conceptual art and was an early champion of feminist art. Her book Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 remains a seminal text on the subject.

Conceptual art also reacted against the commodification of art, attempting subversion of the gallery or museum as the location and determiner of art and the art market as the owner and distributor of art. Many conceptual artists’ work can therefore only be known through documentation such as photographs, written texts, or displayed objects, which some might argue are not in themselves the art. Conceptual art is sometimes reduced to a set of written instructions describing a work without actually making it, emphasizing the notion of the idea as more important than the artifact.

Precursors

French artist Marcel Duchamp paved the way for the conceptualists, providing examples of prototypically conceptual works such as the ready-mades. The most famous of Duchamp’s ready-mades was Fountain (1917), a standard urinal basin signed by the artist with the pseudonym “R.Mutt” and submitted for inclusion in the annual, unjuried exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York. (It was rejected.) In traditional terms, a commonplace object such as a urinal cannot be art because it is not made by an artist or with any intention of being art, nor is it unique or handcrafted. Duchamp’s relevance and theoretical influence for future “conceptualists” was later acknowledged by US artist Joseph Kosuth in his 1969 essay, “Art After Philosophy,” when he wrote, “All art (after Duchamp) is conceptual (in nature) because art only exists conceptually.”

Historical Examples

In 1953, artist Robert Rauschenberg created Erased De Kooning Drawing, which was literally a drawing by Willem de Kooning that Rauschenberg erased. It raised many questions about the fundamental nature of art, challenging the viewer to consider whether erasing another artist’s work could be a creative act, as well as whether the work was only “art” because the famous Rauschenberg had done it.

In 1960, Yves Klein carried out an action called A Leap IntoThe Void, in which he attempted to fly by leaping out of a window. As with much of conceptual art, the performance is largely presented through its documentation. In 1961, Robert Rauschenberg sent a telegram to the Galerie Iris Clert which said: “This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so” as his contribution to an exhibition of portraits. In 1969, Vito Acconci created Following Piece, in which he followed random members of the public until they disappeared into a private space. The piece is presented as photographs.

Contemporary Influence

The first wave of the conceptual art movement extended from approximately 1967 to 1978. Early concept artists like Henry Flynt, Robert Morris, and Ray Johnson influenced the later movement of conceptual art. Conceptual artists like Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, and Lawrence Weiner have proven influential on subsequent artists, and well-known contemporary artists such as Mike Kelley and Tracey Emin are sometimes labeled second- or third-generation conceptualists or post-conceptual artists.

Contemporary artists have addressed many of the concerns of the conceptual art movement. While they may or may not term themselves conceptual artists, ideas such as anti- commodification, social and/or political critique, and ideas/information as medium continue to be aspects of contemporary art, especially among artists working with installation art, performance art, net art, and electronic/digital art.

Minimalism

The term minimalism is used to describe a trend in design and architecture in which the subject is reduced to its necessary elements.

Key Points

- Minimalist design has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture. In addition, the work of De Stijl artists is a major source of reference for this style.

- The term minimalism dates to the early 19th century and gradually became an important movement in response to the ornate design of the previous period. Minimalist architecture became popular in the late 1980s in London and New York.

- The concept of minimalist architecture is to strip everything down to its essential qualities to achieve simplicity.

- Zen concepts of simplicity transmit the ideas of freedom and essence of living. Simplicity is not only an aesthetic value, it has a moral perception that looks into the nature of truth and reveals the inner qualities of materials and objects.

Key Terms

- Zen: A philosophy of calm reminiscent of that of the Buddhist denomination.

- aesthetic: Concerned with beauty, artistic impact, or appearance.

The term minimalism can be used to describe a trend in design and architecture in which the subject is reduced to only its necessary elements. Minimalist design in the west has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture. In addition, the work of De Stijl artists is a major source of reference for this style. De Stijl expanded the ideas that could be expressed by using basic elements such as lines and planes organized in very particular manners.

Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe adopted the motto “less is more” to describe his aesthetic of arranging the numerous necessary components of a building to create an impression of extreme simplicity. By enlisting every element and detail to serve multiple visual and functional purposes, such as designing a floor to also serve as the radiator or a massive fireplace to also house the bathroom, spaces become visually pared down and highly functional.

Minimalist architecture became popular in the late 1980s in London and New York, a few decades after the movement’s prevalence in other art forms. White elements, cold lighting, large open spaces with minimal objects and furniture, and a simplified living space revealed the essential quality of buildings and attitudes toward life. While ornamentation is spare, it’s not totally absent. Instead this style maintains the idea that all parts, details, and joinery have been reduced such that nothing could be further removed to improve the design.

Minimalist design and architecture accounts for light, form, material, space and location. In minimalist architecture, design elements convey the message of simplicity. The basic geometric forms, elements without decoration, simple materials and repetitions of structures represent a sense of order and essential quality. The movement of natural light in buildings reveals simple and clean spaces. In late 19th century, as the arts and crafts movement became popularized in Britain, people valued the attitude of “truth to materials.” Minimalist architects humbly listen to figure, seeking essence and simplicity by rediscovering the valuable qualities in simple common materials.

The idea of simplicity appears in many cultures, especially the Japanese traditional culture of Zen Philosophy. Zen concepts of simplicity transmit the ideas of freedom and essence of living. Simplicity is not only an aesthetic value, but has a moral perception that considers the nature of truth and reveals the inner qualities of materials and objects for their essence. For example, the dry rock garden in Ryoan-ji temple demonstrates the concepts of simplicity from the considered setting of a few stones and a huge empty space.

Minimalism in Art

Minimalism as a movement in art is primarily identified in the late 1960s and 1970s with artists like Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, and Robert Morris. The objects of Donald Judd were often manufactured by others and installed by the artist. Sculpture was reductive and geometric, often rectangular metal boxes. Agnes Martin made paintings and drawings within the minimalist aesthetic by using primarily thin lines in repetitive patterns on a pale background. Stressing the basic materiality of either sculpture or painting stripped away what might have been seen as decorative or pretentious in Abstract Expressionism, for example.

Process Art or Post-Minimalism

Process-based art focuses on the creative journey instead of the end product.

Learning Objectives

- Contrast the focus of process art with that of product-focused artists.

Key Points

- The processes involved in creating art are any actions used to make a work of art.

- The process art movement began in the U.S. and Europe in the mid-1960s. It has roots in performance art and Dadaism.

- In process art, the ephemeral nature and insubstantiality of materials are often showcased and highlighted.

- Process art and environmental art are directly related. Process artists engage the primacy of organic systems, using perishable, insubstantial, and transitory materials.

Key Terms

- ephemeral: Something which lasts for a short period of time, fleeting.

Background

Process art is an artistic movement and creative sentiment in which end product is not the primary focus. The processes referred to are those of creating art: the gathering, sorting, collating, associating, patterning, and the initiation of actions that must be in place. Process art is concerned with actual creation and how actions can be defined as art, seeing the expression of the artistic process as more significant than the product created by the process. Process art often focuses on motivation, intent, the rationale, with art viewed as a creative journey that doesn’t necessarily lead to a traditional fine art object destination.

Process Art Movement

The process art movement began in the U.S. and Europe in the mid-1960s. It has roots in performance art, the Dada movement and, more traditionally, the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock. Change, transience, and embracing serendipity are themes in this movement. In 1968, the Guggenheim Museum hosted a groundbreaking exhibition and essay defining the movement by Robert Morris, noting: “Process artists were involved in issues attendant to the body, random occurrences, improvisation, and the liberating qualities of nontraditional materials such as wax, felt, and latex. Using these, they created eccentric forms in erratic or irregular arrangements produced by actions such as cutting, hanging, and dropping, or organic processes such as growth, condensation, freezing, or decomposition.”

In process art, the ephemeral nature and insubstantiality of materials are often showcased and highlighted. Process art and environmental art are directly related: process artists engage the primacy of organic systems, using perishable, insubstantial, and transitory materials such as dead rabbits, steam, fat, ice, cereal, sawdust, and grass. The materials are often left exposed to natural forces like gravity, time, weather, or temperature in order to celebrate natural processes. The emphasis on material put these artists in contrast to the minimalists and so are sometimes also called Post-Minimal.

Eva Hesse came to America with her parents, observant Jews, to escape Nazi Germany in 1939. She studied at a number of institutions but completed a BA from Yale. Her work recalls the human body in abstract ways; shapes made of fiberglass and latex suggest interiors, like those of the body. She died at 34 of a brain tumor, but left behind a body of work over one decade that remains influential.

Process Art Precedents

Inspiring precedents for process art that are fundamentally related include indigenous rites, shamanic and religious rituals, and cultural forms such as sandpainting, sun dance, and tea ceremonies. For example, the construction process of a Vajrayana Buddhist sand mandala by monks from Namgyal Monastery in Ithaca, New York was recorded and exhibited online by the Ackland’s Yager Gallery of Asian Art. The monks’ creation of a Medicine Buddha mandala began February 26, 2001 and concluded March 21, 2001, and the dissolution of the mandala was on June 8, 2001, demonstrating that the process of creating the art was more important than preserving the finished product.

The Influence of Feminism

Feminist and intersectional sentiments in art have always existed in opposition to the white, patriarchal foundations and current realities of western art markets and art history.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the origin, evolution, and influence of the feminist art movement during the late 20th century.

Key Points

- Feminism in art has always sought to change the reception of contemporary art and bring visibility to women within art history and practice.

- In line with the development of western civilization, art in the west has been built upon white, patriarchal, capitalist values, and while women artists have always existed they have largely been omitted from history.

- The women-in-arts movement corresponded with general developments in feminism in the 1960s and 1970s.

- One of the first self-proclaimed feminist art classes in the United States was started in the fall of 1970 at Fresno State University by visiting artist Judy Chicago. The students who formed the program included Susan Boud, Dori Atlantis, Gail Escola, Vanalyne Green, Suzanne Lacy, and Cay Lang.

- The strength of the feminist movement allowed for the emergence and visibility of many new types of work by women.

- From 1980 onward, art historian Griselda Pollock challenged the dominant museum models of art and history so excluding of women’s artistic contributions. She helped articulate the complex relations between femininity, modernity, psychoanalysis, and representation.

Key Terms

- feminism: A social theory or political movement supporting the equality of both sexes in all aspects of public and private life; specifically, a theory or movement that argues that legal and social restrictions on females must be removed in order to bring about such equality.

Origins

Feminism in art has always sought to change the reception of contemporary art and bring visibility to women within art history and practice. In line with the development of western civilization, art in the west has been built upon white, patriarchal, capitalist values, and while women artists have always existed they have largely been omitted from history. Feminism has always existed and generally prioritizes the creation of an opposition to this system. Corresponding with general developments within feminism, the so-called “second wave” of the movement gained some prominence in the 1960s and flourished throughout the 1970s.

The Feminist Art Program

One of the first self-proclaimed feminist art classes in the United States, the Feminist Art Program, was started in the fall of 1970 at Fresno State University by visiting artist Judy Chicago. Chicago (born 1939) is an American feminist artist and writer known for her large collaborative art installation pieces which examine the role of women in history and culture. Chicago’s work incorporates artistic skills stereotypically placed upon women, such as needlework, contrasted with stereotypical male skills such as welding and pyrotechnics. Chicago’s masterpiece work is a mixed-media piece known as The Dinner Party, which is in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

The students who formed the Feminist Art Program along with Judy Chicago included Susan Boud, Dori Atlantis, Gail Escola, Vanalyne Green, Suzanne Lacy, and Cay Lang. The group refurbished an off-campus studio space in downtown Fresno for artists to create and discuss their work “without male interference”. Participants lived and worked in the studio, leading reading groups and collaborating on art. In 1971, the class became a full-time program at the university.

The program was different than a standard art class. Instead of the typical teaching of techniques and art history, students focused on raising their feminist consciousness. Students would share personal experiences about specific topics like money and relationships. It was believed that by sharing these experiences, students were able to insert more emotion into their artwork. Furthermore, instead of supporting the typical idea of artists being secluded and working as independent “geniuses,” the class emphasized collaboration, a radical departure for the time period.

Feminist Art Movements: U.S and Europe

During the heyday of second wave feminism, women artists in New York began to come together for meetings and exhibitions. Collective galleries like A.I.R. Gallery were formed to provide visibility for art by feminist artists. The strength of the feminist movement allowed for emergence and visibility of many new types of work by women. Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) formed in 1969 to protest the lack of exposure for women artists. The Ad Hoc Women Artists’ Committee (AWC) formed in 1971 to address the Whitney Museum’s exclusion of women artists.

There are thousands of examples of women associated with the feminist art movement. Artists and writers credited with making the movement visible in culture include:

- Judy Chicago, founder of the first known Feminist Art Program

- Miriam Schapiro, co-founder of the Feminist Art Program at Cal Arts

- Sheila Levrant de Bretteville and Arlene Raven, co-founders of the Woman’s Building

Both Suzanne Lacy and Faith Wilding were participants in all the early arts’ programs. Other important names include Martha Rosler, Mary Kelly, Kate Millett, Nancy Spero, Faith Ringgold, June Wayne, Lucy Lippard, Griselda Pollock, and art-world agitators The Guerrilla Girls.

The Women’s Interart Center in New York, meanwhile, is still in operation, while the Women’s Video Festival was held in New York City for a number of years during the early 1970s. Many women artists continue to organize working groups, collectives, and nonprofit galleries in various locales around the world.

From 1980 onward, art historian Griselda Pollock challenged the dominant museum models of art and history so excluding of women’s artistic contributions. She helped articulate the complex relations between femininity, modernity, psychoanalysis, and representation. While many argued with the initial feminist movement’s focus and use of women’s bodies as subject matter suggesting that it was still subjecting women to the patriarchal gaze, artists at the time considered it a reassertion of agency – by taking back the images of women’s bodies from the historical use they found it empowering and fundamentally transgressive.

Current Climate

Things are beginning to shift in terms of a more gender-balanced art world as postmodern thought and gender politics become more important to the general public. Postmodern feminism is an approach to feminist theory that incorporates postmodern and post-structuralist theory, and thus sees itself as moving beyond the modernist polarities of liberal feminism and radical feminism towards a more intersectional concept of reality.

Land Art or Earth Art

Site-specific art refers to art that has been created for a specific environment or space.

Key Points

- Site-specific art is artwork created to exist in a certain place. Typically, the artist takes the location into account while planning and creating the artwork.

- The actual term was promoted and refined by Californian artist Robert Irwin, but it was actually first used in the mid-1970s by young sculptors such as Patricia Johanson, Dennis Oppenheim, and Athena Tacha.

- Outdoor site-specific artworks often include landscaping combined with permanently sculptural elements. Site-specific art can be linked with environmental art, Earth art, or land art.

- Robert Smithson and Christo and Jeanne Claude are land/Earth artists who created site-specific work.

Key Terms

- topographies: Detailed graphic representations of the surface features of a place or object.

Site-specific art is artwork created to exist in a certain place. Typically, the artist takes the location into account while planning and creating the artwork. The actual term was promoted and refined by Californian artist Robert Irwin, but it was actually first used in the mid-1970s by young sculptors, such as Patricia Johanson, Dennis Oppenheim, and Athena Tacha, who executed public commissions for large urban sites. Architectural critic Catherine Howett and art critic Lucy Lippard were among the first to describe site-specific environmental art as a movement.

Background

Site-specific art emerged as a reaction to the proliferation of modernist art objects as transportable, nomadic, museum-oriented, objects of commodification, with the desire to draw attention to the site and the context of the art. Site-specific work can refer to any form of art as long as it has been created for a specific environment or space. Closely related to land art and environmental art movements, site-specific art is the broadest of the three as it is not medium-specific.

Land Art and Earth Art

Land art, earthworks (coined by Robert Smithson), or Earth art is an art movement in which landscape and of art are inextricably linked, so in this way it is site-specific. It is also an art form created in nature, using organic materials such as soil, rock (bed rock, boulders, stones), organic media (logs, branches, leaves), and water with introduced materials such as concrete, metal, asphalt, or mineral pigments. Sculptures are not placed in the landscape; rather, the landscape is the means of their creation. Earth-moving equipment is often involved. The works frequently exist in the open, located well away from civilization, left to change and erode under natural conditions. Many of the first works of this kind, created in the deserts of Nevada, New Mexico, Utah or Arizona, were ephemeral in nature and now only exist as video recordings or photographic documents.

Robert Smithson (January 2, 1938 – July 20, 1973) was an American land artist. His most famous work is Spiral Jetty (1970), a 1,500-foot long spiral-shaped jetty extending into the Great Salt Lake in Utah constructed from rocks, earth, and salt. It was entirely submerged by rising lake waters for several years, but has since re-emerged.

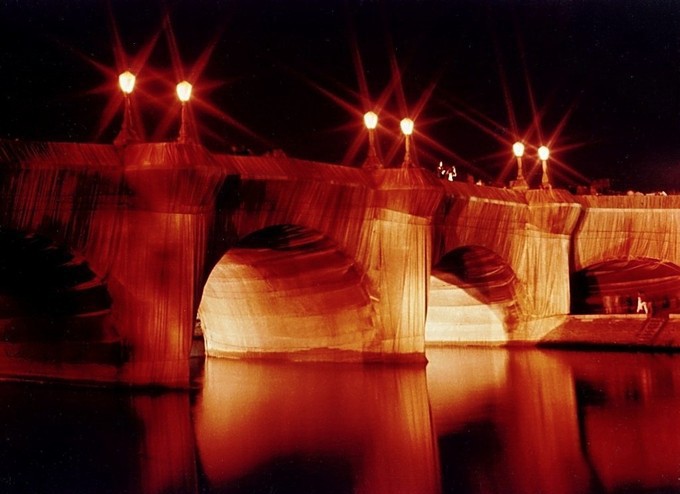

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude, known as Christo and Jeanne-Claude, are a married couple who created site-specific environmental works of art. Their works nearly always entail wrapping a large area of space or piece of architecture in a textile, and include the wrapping of the Reichstag in Berlin and the Pont-Neuf bridge in Paris, the 24-mile (39 km)-long artwork called Running Fence in Sonoma and Marin counties in California, and The Gates in New York City’s Central Park. The purpose of their art, they contend, is simply to create works of art for joy and beauty and to create new ways of seeing familiar landscapes.

Postmodernism

Post-Modern Architecture

The ideas of Postmodernism based on the ideas of French philosophers like Jacques Derrida (deconstruction) arguably first appeared in architecture of the 1980’s. Buildings like the Beaubourg Center in Paris by Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers and Gianfranco Franchini was completed in 1977. It’s inside-out structure with most of the internal mechanical and functional systems exposed on the exterior seemed to coincide with the deconstructionist ideas of Derrida. It houses much of Frances contemporary art.

Race and Ethnicity in Postmodernism

Postmodernism had a profound influence on the concepts of race and ethnicity in the United States in the mid-20th century.

Key Points

- Postmodernism relies on concrete experience over abstract principles, arguing that the outcome of one’s own experience will necessarily be fallible and relative rather than certain or universal.

- A great deal of art during this era sought to deconstruct race through a postmodern lens, arguing that race is not based in any biological reality but is instead a socially constructed category.

- Primarily through a postmodern perspective, the author bell hooks has addressed the intersection of race, class, and gender in education, art, history, sexuality, mass media, and feminism.

- The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s led artists to express the ideals of the times. Galleries and community art centers were developed for the purpose of displaying African-American art, and collegiate teaching positions were created by and for African- American artists.

- By the 1980s and 1990s, hip-hop graffiti became predominate in urban communities. Most major cities developed museums devoted to African American artists. The National Endowment for the Arts provided increasing support for these artists.

- Post-black art is a phrase that refers to a category of contemporary African-American art. It is a paradoxical genre in which race and racism are intertwined in a way that rejects their interaction.

Key Terms

- bell hooks: Born Gloria Jean Watkins (1952 – ); an American author, feminist, and social activist; known for her focus on the interconnectivity of race, capitalism, and gender and their ability to perpetuate systems of oppression.

- deconstruction: A philosophical theory of textual criticism; a form of critical analysis.

- post-structuralism: A doctrine that rejects structuralism’s claims to objectivity and emphasizes the plurality of meaning.

Background

Postmodernism (also known as post-structuralism) is skeptical of explanations that claim to be valid for all groups, cultures, traditions, or races, and instead focuses on the relative truths of each person (i.e. Postmodernism = relativism). In the postmodern understanding, interpretation is everything; reality only exists through our interpretations of what the world means to us individually. Postmodernism relies on concrete experience over abstract principles, arguing that the outcome of one’s own experience will necessarily be fallible and relative rather than certain or universal.

Postmodernism frequently serves as an ambiguous, overarching term for skeptical interpretations of culture, literature, art, philosophy, economics, architecture, fiction, and literary criticism. It is often associated with deconstruction and post-structuralism because its usage gained significant popularity at the same time as 20th-century post-structural thought.

Postmodernism postulates that many, if not all, apparent realities are only social constructs and therefore subject to change. It claims that there is no absolute truth and that the way people perceive the world is subjective and emphasizes the role of language, power relations, and motivations in the formation of ideas and beliefs. In particular, it attacks the use of binary classifications such as male versus female, straight versus gay, white versus black, and imperial versus colonial; it holds realities to be plural, relative, and dependent on who the interested parties are and the nature of these interests. Postmodernist approaches consider that the ways in which social dynamics, such as power and hierarchy, affect human conceptualizations of the world have important effects on the way knowledge is constructed and used. Postmodernist thought often emphasizes constructivism, idealism, pluralism, relativism, and skepticism in its approaches to knowledge and understanding.

Postmodernism and Race

Postmodernism had a profound influence on the concepts of race and ethnicity in the United States in the mid-20th century. Many people began to reconceptualize the term “race” as a social construct – meaning that it has no inherent biological reality, but is a classification system that’s been constructed or invented for societal purposes. Following the Second World War, evolutionary and social scientists were acutely aware of how beliefs about race were used to justify discrimination, apartheid, slavery, and genocide. This questioning gained momentum in the 1960s during the U.S. civil rights movement and the emergence of numerous anti-colonial movements worldwide.

A great deal of art during this era sought to deconstruct race through a postmodern lens. The author bell hooks is widely known for her writing focused on the connection of race, capitalism, and gender and what she describes as their ability to produce and perpetuate systems of oppression and class domination. She has published more than 30 books and numerous scholarly and mainstream articles, appeared in several documentary films, and participated in various public lectures. Primarily through a postmodern perspective, hooks has addressed race, class, and gender in education, art, history, sexuality, mass media, and feminism.

Some African-American artists began taking a global approach after World War II. Artists such as Barbara Chase-Riboud, Edward Clark, Harvey Cropper, and Beauford Delaney worked and exhibited abroad in Paris, Copenhagen, and Stockholm. Other African-American artists made it into important New York galleries by the 1950s and 1960s: Horace Pippin and Romare Bearden were among the few who were successfully received in a gallery setting. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s led artists to capture and express the times and changes. Galleries and community art centers were developed for the purpose of displaying African- American art, and collegiate teaching positions were created by and for African-American artists.

Post-black art arose during this time as a category of contemporary African-American art. It is a paradoxical genre of art where race and racism are intertwined in a way that rejects their interaction. By the 1980s and 1990s, hip-hop graffiti became predominate in urban communities. Most major cities had developed museums devoted to African American artists. The National Endowment for the Arts provided increasing support for these artists.

Postmodernist Sculpture

The characteristics of Postmodernism, such as collage, pastiche, appropriation, and the destruction of barriers between fine art and popular culture, can be applied to sculptural works.

Key Points

- While inherently difficult to define by nature, Postmodernism began with pop art and continued within many following movements including conceptual art, neo- expressionism, feminist art, and the young British artists of the 1990s.

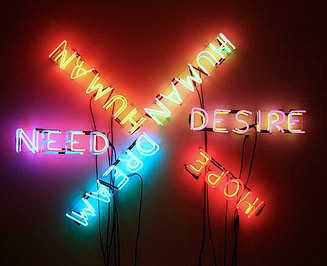

- Intermedia, installation art, conceptual art, video, light art, and sound art are often regarded as postmodern mediums.

- In the 1960s and 1970s artists like Eduardo Paolozzi, Chryssa, Claes Oldenburg, George Segal, Edward Kienholz, Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, Duane Hanson, and John DeAndrea explored abstraction, imagery, and figure by using video art, environment, light sculpture, and installation art in new ways.

- Jeff Koons is a good example of a postmodern sculptor; his works elevate the mundane, contain a heavy dose of kitsch, and project an element of ambiguous cynicism often seen in postmodern works.

Key Terms

- postminimalist: One who works in the style of postminimalism.

- kinetic: Of or relating to motion.

Background

The characteristics of Postmodernism, include bricolage, collage, appropriation, the recycling of past styles and themes in a modern-day context, and destruction of the barriers between fine arts, craft and popular culture, can be applied to sculpture. While inherently difficult to define by nature, Postmodernism began with pop art and continued within many following movements including conceptual art, neo-expressionism, feminist art, and the young British artists of the 1990s. The plurality of idea and form that defines Postmodernism essentially allow any medium to be considered postmodern. In terms of sculpture, characteristics like mixed media, installation art, conceptual art, video light art, and sound art are often regarded as postmodern.

Jeff Koons

Jeffrey “Jeff” Koons (born January 21, 1955) is an American artist known for working with popular culture subjects and reproducing banal objects, such as balloon animals produced in stainless steel with mirror-finish surfaces. His works have sold for substantial sums, including at least one world record auction price for a work by a living artist.

Koons gained recognition in the 1980s and subsequently set up a factory-like studio in a SoHo loft on the corner of Houston Street and Broadway in New York. It was staffed with over 30 assistants, each assigned to a different aspect of producing his work, in a similar mode as Andy Warhol’s Factory (notable because all of his work is produced using a method known as art fabrication). Today, he has a 16,000-square-foot factory near the old Hudson rail yards in Chelsea, working with 90 to 120 regular assistants. Koons developed a color-by-numbers system so that each of his assistants could execute his canvases and sculptures as if they had been done “by a single hand”.

Koons is a good example of a postmodern sculptor because his works elevate the mundane, contain a heavy dose of kitsch, and project an element of ambiguous cynicism often seen in Postmodern works.

Neo-Expressionism

Neo-expressionists sought to portray recognizable subjects in rough and violently emotional ways using vivid color schemes.

Key Points

- Related to American lyrical abstraction, the Bay Area Figurative School, the continuation of abstract expressionism, new image painting, and pop art, neo-expressionism developed as a reaction against the conceptual art and minimal art of the 1970s.

- Critics questioned neo-expressionism’s relation to marketability, the rapidly expanding art market, celebrity, the backlash against feminism, anti-intellectualism, and a return to mythic subjects and individualist methods that some deemed outmoded.

- Women were marginalized by the movement, with painters such as Elizabeth Murray and Maria Lassnig omitted from many key exhibitions.

- The return to traditional painting in the late 1970s and early 1980s seen in neo- expressionist artists such as Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel is described as having had postmodern tendencies.

- Neo-expressionism’s strong links to the commercial art market has raised questions about its status as a postmodern movement and about the definition of Postmodernism itself.

Key Terms

- outmoded: Something that is considered unfashionable.

- neo-expressionism: A style of modern painting and sculpture that emerged in the late 1970s and dominated the art market until the mid-1980s; characterized by portraying recognizable objects like the human body in rough and violently emotional ways using vivid color schemes.

- bay: An opening in a wall, especially between two columns; the distance between two supports in a vault or building with a pitched roof.

Background

Neo-expressionism is a style of modern painting and sculpture that emerged in the late 1970s and dominated the art market until the mid-1980s. Related to American lyrical abstraction of the 60s and 70s, the Bay Area Figurative School of the 50s and 60s, the continuation of abstract expressionism, new image painting, and pop art, neo-expressionism developed as a reaction against the conceptual and minimalist art of the 1970s. Neo-expressionists returned to portraying recognizable objects such as the human body (though sometimes an abstracted version), in rough and violently emotional ways using vivid colors and color harmonies.

Overtly inspired by so-called German expressionist painters such as Emil Nolde, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and other expressionist artists such as James Ensor and Edvard Munch, neo-expressionists were sometimes called Neue Wilden (“the new wild ones’”). The style emerged internationally and was viewed by critics as a revival of traditional themes of self-expression in European art after decades of American dominance. The social and economic value of the movement was hotly debated. Critics questioned neo-expressionism’s relation to marketability, the rapidly expanding art market, celebrity, the backlash against feminism, anti-intellectualism, and a return to mythic subjects and individualist methods that some deemed outmoded. Women were marginalized in the movement, with painters such as Elizabeth Murray and Maria Lassnig omitted from many of its key exhibitions, most notoriously from the 1981 “New Spirit in Painting” exhibition in London that included 38 male painters and no female painters.

Neo-Expressionism Around the World

Georg Baselitz, born January 1938, is a German painter who studied in the former East Germany before moving to West Germany. Baselitz’s style is interpreted as neo-expressionist, but from a European perspective it is seen as postmodern. His career was amplified in the 1960s after the police took action against one of his paintings because of its provocative and offensive sexual nature.

Neo-Expressionism As Postmodern Art?

The return to traditional painting in the late 1970s and early 1980s seen in neo-expressionist artists such as Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel has been described as one of the first coherent postmodern movements. Its strong link to the commercial art market has raised questions about its status as a postmodern movement and about the definition of Postmodernism itself. Hal Foster stated that Neo-Expressionism was complicit with the conservative cultural politics of the Reagan-Bush era in the U.S. Félix Guattari disregarded the “large promotional operations dubbed ‘Neo-Expressionism’ in Germany” as an example of a “fad that maintains itself by means of publicity…Postmodernism is nothing but the last gasp of Modernism.”

These critiques of Neo-Expressionism reveal that money and public relations strained the credibility of the contemporary art world in America during the same period that conceptual artists and women artists including painters and feminist theorists like Griselda Pollock were systematically reevaluating modern art. Brian Massumi claims that Deleuze and Guattari opened the horizon for new definitions of beauty in postmodern art. For Jean-François Lyotard, paintings by Valerio Adami, Daniel Buren, Marcel Duchamp, Bracha Ettinger, and Barnett Newman, and the painting of Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky, were the vehicles for new ideas of the sublime in contemporary art.

Political Art

Political art in the nineties was a form of protest for queer and feminist movements against the patriarchy.

Key Points

- The 90s saw a continuation of political art whereby stigmatized communities such as racial minorities, women, and LGBT individuals created what is termed political art in opposition to the patriarchy.

- The Guerrilla Girls are an anonymous group of feminist, female artists devoted to fighting sexism and racism within the art world.

- The LGBT community responded to the AIDS crisis by organizing, engaging in direct actions, staging protests, and creating political art.

- Street art can be a powerful platform for reaching the public and a potent form of political expression for the oppressed.

Key Terms

- feminism: A social theory or political movement supporting the equality of both sexes in all aspects of public and private life; specifically, a theory or movement that argues that legal and social restrictions on females must be removed in order to bring about such equality.

Background

A strong relationship between the arts and politics has existed across cultural boundaries and throughout history. Artistic responses to contemporaneous events take on political and social dimensions, becoming a focus of controversy and even a force of political and social change. The 1990s saw a continuation of political art around the world. Stigmatized communities such as racial minorities, women, and the LGBT individuals created political art in opposition to the patriarchy.

The notion that personal revelation through art can be a political tool guided activist art in its study of public dimensions and private experience. The strategies deployed by feminist artists paralleled those of other activist artists, including “collaboration, dialogue, a constant questioning of aesthetic and social assumptions, and a new respect for audience.” These were used to articulate and negotiate issues of self-representation, empowerment, and community identity.

The Guerrilla Girls

The Guerrilla Girls are an anonymous group of feminist, female artists devoted to fighting sexism and racism within the art world. The group formed in New York City in 1985 with the mission of bringing gender and racial inequality in the fine arts into focus within the greater community. Members are known for the gorilla masks they wear to remain anonymous.

Throughout their existence, the Guerrilla Girls have utilized protest art to express their ideals, opinions, and concerns, as well as to fundraise for the group. Their posters, which now are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and others they once protested against, are known for their bold statements such as, “When racism and sexism are no longer fashionable, what will your art collection be worth?” In the early days, posters were brainstormed, designed, critiqued and posted around New York. Small handbills based on their designs were also passed out at events by the thousands.

In 1990, the group designed a billboard featuring Mona Lisa that was placed along the West Side Highway, supported by the New York City public art fund. For one day, New York’s MTA Bus Company also displayed bus advertisements asking, “Do women have to get naked to get into the Met Museum?” Stickers also became popular calling cards representative of the group. In the mid-1980s members infiltrated the Guggenheim Museum bathrooms and placed stickers about female inequality on the walls.

Since 2002, Guerrilla Girls, Inc. has designed and installed billboards in Los Angeles during the Oscars to expose white male dominance in the film industry, such as: “Anatomically Correct Oscars,” “Even the Senate is More Progressive than Hollywood,” and “The Birth of Feminism, Unchain the Women Directors. ” Guerrilla Girls have also published books that include their statistical data, information about protest arts, and goals regarding inequality in the art world. Their first book, Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls.

LGBT Rights and the AIDS Crisis

The AIDS crisis of the 1980s led to increasing stigma against the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community, who in turn protested with political art and activism.

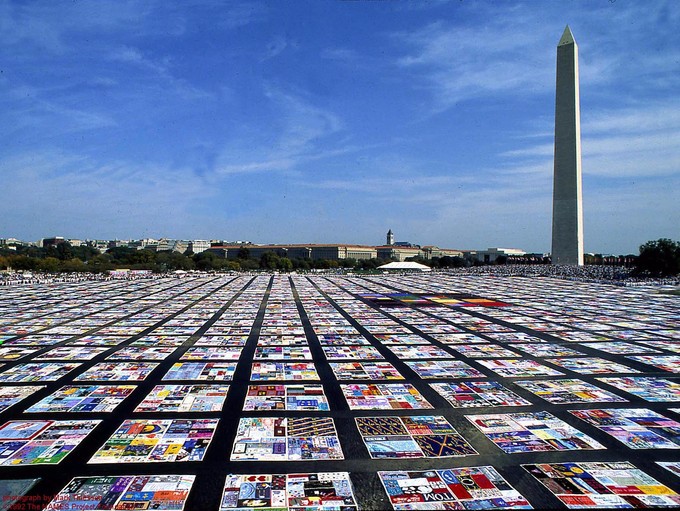

The LGBT community responded to the AIDS crisis by organizing, engaging in direct actions, staging protests, and creating political art. Some of the earliest attempts to bring attention to the new disease were staged by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a protest and street performance organization that uses drag and religious imagery to call attention to sexual intolerance and satirize issues of gender and morality. At the group’s inception in 1979, a small group of gay men in San Francisco began wearing the attire of nuns in visible situations, using high camp to draw attention to social conflicts and problems in the Castro District.

One of their most enduring projects of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence is the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, in which members who have died (referred to as “Nuns of the Above”) are immortalized. Created in the early 1990s, the quilt has frequently been flown around the United States for local displays.

A number of young artists who themselves were victims of AIDS made art that brought attention to the issue. Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz and Robert Mapplethorpe were artists who succumbed to the disease but created lasting work that brought attention to an issue that was for too long ignored by the politicians given the populations most affected by it at that time, and also especially in the case of Mapplethorpe – creating a Foundation for the arts and ongoing research into the disease.

Street Art or Graffiti

Street art is an umbrella term defining forms of visual art created in public locations, usually unsanctioned artwork executed outside of the context of traditional art venues. The term gained popularity during the graffiti art boom of the early 1980s. The terms “urban art”, “guerrilla art”, “post-graffiti” and “neo-graffiti” are also sometimes used when referring to artwork created in these contexts.

There is a strong current of activism and subversion in urban art, as it can be a powerful platform for reaching the public and a potent form of political expression for the oppressed. Some street artists use “smart vandalism” as a way to raise awareness of social and political issues, especially around issues of race and racism. Street artists sometimes present socially relevant content infused with aesthetic value to attract attention to a cause or as a form of “art provocation.” Street art is a controversial issue: some people consider it a crime, others consider it a form of art. Graffiti art proved to be one of the most lucrative kinds of work for the small galleries on the cutting edge on the Lower East Side in the 80s and 90s. It continues to be popular today as witnessed by the recent sale of a Banksy which he engineered to self-destruct in a gesture against the commodification of what had been a purely rhetorical and political art form.

Performance and Body Art

Performance emerged alongside conceptual art to challenge notions of institutional visual art.

Key Points

- Conceptual art emerged as a movement during the 1960s. In part, it was a reaction against formalism as articulated by the influential New York art critic Clement Greenberg.

- Some have argued that conceptual art continued this dematerialization of art by removing the need for objects altogether, while others, including many of the artists themselves, saw conceptual art as a radical break with Greenberg’s kind of formalist Modernism.

- Performance art is traditionally an interdisciplinary performance presented to an audience. It may be scripted or unscripted, random or carefully orchestrated, spontaneous or planned, and occur with or without audience participation. It generally involves the body of the artist herself.

Key Terms

- conceptual: Of, or relating to concepts or mental conception; existing in the imagination.

Background

Performance art is a traditionally interdisciplinary performance presented to an audience. It may be scripted or unscripted, random or carefully orchestrated, spontaneous or otherwise planned, and occur with or without audience participation. The performance can be live or distributed via media; the performer can be present or absent. Any situation that involves the four basic elements of time, space, the performer’s body or presence in a medium, and a relationship between the performer and the audience can be considered performance art. It can happen anywhere, in any venue or setting, and for any length of time.

Contemporary Influence In Conceptual and Performance Art

The first wave of the conceptual art movement extended from approximately 1967 to 1978, influenced by early concept artists like Henry Flynt, Robert Morris, and Ray Johnson. Conceptual artists like Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, and Lawrence Weiner have proven very influential on subsequent artists, and well-known contemporary artists such as Mike Kelley or Tracey Emin are sometimes labeled “second- or third-generation” conceptualists, or post-conceptual artists.

Contemporary artists have adopted many of the concerns of the conceptual art movement. While these artists may or may not identify themselves as conceptual artists, ideas such as anti- commodification, social and political critique, and ideas/information as medium continue to have a place in contemporary art, especially among artists working with installation art, performance art, net art, and digital art.

Visual Arts, Performing Arts, and Art Performance

Performance art is an essentially contested concept: any single definition implies the recognition of rival uses. Like concepts such as ”democracy” or “art,” it implies productive disagreement with itself.

The narrower meaning of the term refers to postmodernist traditions in Western culture. From about the mid-1960s into the 1970s, performance art often derived from concepts of visual art, with respect to Antonin Artaud, Dada, the Situationists, Fluxus, installation art, and conceptual Art. It was often defined as the antithesis to theatre, challenging orthodox art forms and cultural norms. The ideal was an ephemeral and authentic experience for the performer and audience in an event that could not be repeated, captured, or purchased.

Performance artists often challenge the audience to think in new and unconventional ways, break conventions of traditional arts, and break down conventional ideas about “what art is.” As long as the performer does not become a player who repeats a role, performance art can include satirical elements (compare Blue Man Group); utilize robots and machines as performers, as in pieces of the Survival Research Laboratories; or borrow elements of any performing arts such as dance, music, and circus.

Video Art

Video art relies on moving pictures and is comprised of video and/or audio data.

Key Points

- Video art came into existence during the late 1960s and early 1970s as new technology became available outside corporate broadcasting.

- This form can consist of recordings that are broadcast, viewed in galleries, or distributed as video tapes or DVD discs; sculptural installations incorporating one or more television sets or video monitors; and performances in which video representations are included.

- Many artists found video more appealing than film, particularly when the medium ‘s greater accessibility was coupled with technologies able to edit or modify the video image.

- Installation works involve either an environment, distinct pieces of video presented separately, or any combination of video with traditional media like sculpture.

Key Terms

- choreography: The art of creating, arranging, and recording dance movements.

- video art: A type of art relying on moving pictures and comprising of video and/or audio data. Video art came into existence during the late 1960s and early 1970s as the new technology became available outside corporate broadcasting.

Video art came into existence during the late 1960s and early 1970s as new technology became available outside corporate broadcasting for the production of moving image work. The medium of video being used to create the work, which can then be broadcast, viewed in galleries, distributed as video tapes or DVD discs, or presented as sculptural installations incorporating one or more television sets or video monitors.

History of Video Art

Prior to the introduction of this new technology, moving image production was only available to the consumer through 8 or 16 millimeter film. Many artists found video more appealing than film, particularly when the medium’s greater accessibility was coupled with technologies able to edit or modify the video image. The relative affordability of video also led to its popularity as a medium.

The first multi-channel video art was Wipe Cycle by Ira Schneider and Frank Gillette. An installation of nine television screens, Wipe Cycle combined live images of gallery visitors, found footage from commercial television, and shots from pre-recorded tapes. The material was alternated from one monitor to the next in an elaborate choreography.

Prominent Video Artists

The first video cameras made available to the public in ca. 1963-65 were given for promotion to Nam June Paik, a Korean-American artist for whom video became his primary medium, and Andy Warhol. Paik and other early video artists explored the medium in much the way early photographers had that technology – screens were manipulated to create colors and shapes as if they were canvases. Today video artists use the medium in many ways; some, like Matthew Barney, create cinematic productions the equal of any narrative film. Many early prominent video artists were involved with concurrent movements in conceptual art, performance, and experimental film. These include Americans Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, and Peter Campus, among others. Some, like Steina and Woody Vasulka, employed video synthesizers to create abstract works.

Much video art in the medium’s heyday experimented formally with the limitations of the format. For example, American artist Peter Campus’ Double Vision combined the video signals from two Sony Portapaks through an electronic mixer, resulting in a distorted and radically dissonant image. Another representative piece, Joan Jonas’ Vertical Roll, involved recording previously-recorded material of Jonas dancing while playing the videos back on a television, resulting in a layered and complex representation of mediation.

Video Art Today

Currently, video art is represented by two varieties: single-channel and installation. Single- channel works are much closer to the conventional idea of television in that a video is screened, projected, or shown as a single image. Installation works, meanwhile, involve either an environment, distinct pieces of video presented separately, or any combination of video coupled with traditional media like sculpture. Installation video is the most common form of video art today. Sometimes it is combined with other media and is often subsumed by the greater whole of an installation. Contemporary contributions are being produced at the crossroads of such disciplines as installation, architecture, design, sculpture, and electronic art.

Digital Art

Digital art describes artistic works and practices that use digital technology as a part of the creative process.

Key Points

- Since the 1970s, digital art has been described with terms like computer art and multimedia art. This modality falls under the umbrella of new media art.

- The impact of digital technology has transformed activities such as painting, drawing, sculpture, and music, while new forms, such as net art, digital installation art, and virtual reality, have become recognized as art.

- The techniques of digital art are used extensively by the mainstream media in advertisements and by filmmakers to produce special effects.

- Digital art can be purely computer-generated or taken from other sources, such as a scanned photograph or an image drawn using graphics software.

Key Terms

- imagery: Visible representations of objects.

- stylus: A sharp stick used in ancient times for writing in clay tablets; a sharp tool for engraving.

Digital art is a general term for any art that uses digital technology as an essential part of the creative process. Since the 1970s, various names have been used to describe such artwork, including computer art and multimedia art, and digital art itself is placed under the larger umbrella term of new media art.

The impact of digital technology has transformed activities such as painting, drawing, sculpture, and music, while new forms (such as net art, digital installation art, and virtual reality) have become recognized as art. More generally, the term digital artist describes one who creates art using digital technologies. The term digital art is also applied to contemporary art that uses the methods of mass production or digital media.

Digital Production Techniques in Visual Media

Techniques of digital art are used extensively by the mainstream media in advertisements and by filmmakers to produce special effects. Both digital and traditional artists use many sources of electronic information and programs to create their work. Given the parallels between visual art and music, it seems likely that acceptance of the value of digital art parallel the progression to acceptance of electronic music over the last four decades.

Digital art can be purely computer-generated or taken from other sources, such as scanned photographs or images drawn using graphics software. The term may technically be applied to art done using other media or processes and merely scanned into a digital format, but digital art usually describes art that has been significantly modified by a computer program. Digitized text, raw audio, and video recordings are usually not considered digital art alone, but can be part of larger digital art projects. Digital painting is created in a similar fashion to non-digital painting uses software to create and distribute the work.

Computer-Generated Visual Media

Digital visual art consists of two-dimensional (2D) information displayed on a monitor as well as information mathematically translated into three-dimensional (3D) images and viewed through perspective projection on a monitor. The simplest form is 2D computer graphics, which reflect drawings made using a pencil and paper. In this case, however, the image is on the computer screen and the instrument used to draw might be a stylus or mouse. The creation might appear to be drawn with a pencil, pen, or paintbrush.

Another kind of digital video art is 3D computer graphics, where the screen becomes a window into a virtual environment of arranged objects that are “photographed” by the computer. Many software programs enable collaboration, lending such artwork to sharing and augmentation so users can collaborate on an artistic creation. Computer-generated animations are created with a computer from digital models. The term is usually applied to works created entirely with a computer. Movies make heavy use of computer-generated graphics, which are called computer- generated imagery (CGI) in the film industry.

Digital installation art constitutes a broad field of activity and incorporates many forms. Some resemble video installations, particularly large-scale works involving projections and live video capture. By using projection techniques that enhance an audience’s impression of sensory development, many digital installations attempt to create immersive environments.

The Globalization of Art

We have seen that developments in art over the centuries have often followed developments in technology. Today the art world is no longer contained by geographical boundaries – it is truly global. Any contemporary art fair will have work from around the world. Recently art from Asia, Africa, India, and the Middle East among many others have become the major players in a world that saw first Italy, then France, then in the 20th century, America, become the center of the art world. Today artists like Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, Palestinian artist Emily Jacir, and Indian artist Shilpa Gupta (see https://youtu.be/WYQ-ysDGZUo) are all making the most avant garde and significant art to be seen and experienced. Curators and critics are also being recruited from far-flung places – the recently deceased Okwui Enwezor must be mentioned – and the Venice Biennale and other important art shows are no longer the purview of the establishment figures of the past. The canon begins to change.