5.7: Early 20th Century in Europe

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 245124

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Rise of Modernism

Modernism was a philosophical movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that was based on an underlying belief in the progress of society.

Key Points

- Among the factors that shaped modernism were the development of modern industrial societies and the rapid growth of cities, followed by the horror of World War I.

- Modernism was essentially based on a utopian vision of human life and society and a belief in progress, or moving forward.

- Modernist ideals pervaded art, architecture, literature, religious faith, philosophy, social organization, activities of daily life, and even the sciences.

- In painting, modernism is defined by Surrealism, late Cubism, Bauhaus, De Stijl, Dada, German Expressionism, and Matisse as well as the abstractions of artists like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky, which characterized the European art scene.

- The end of modernism and beginning of postmodernism is a hotly contested issue, though many consider it to have ended roughly around 1940.

Modernism is a philosophical movement that, along with cultural trends and changes, arose from enormous transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the factors that shaped modernism were the development of modern industrial societies and the rapid growth of cities, followed by the horror of World War I.

Modernism was essentially based on a utopian vision of human life and society and a belief in progress, or moving forward. It assumed that certain ultimate universal principles or truths such as those formulated by religion or science could be used to understand or explain reality.

Modernist ideals were far-reaching, pervading art, architecture, literature, religious faith, philosophy, social organization, activities of daily life, and even the sciences. The poet Ezra Pound’s 1934 injunction to “Make it new!” was the touchstone of the movement’s approach towards what it saw as the now obsolete culture of the past. In this spirit, its innovations, like the stream-of-consciousness novel, atonal (or pantonal) and twelve-tone music, divisionist (or pointillist) painting and abstract art, all had precursors in the 19th century.

In painting, during the 1920s and the 1930s and the Great Depression, modernism is defined by Surrealism, late Cubism, Bauhaus, De Stijl, Dada, German Expressionism, and Modernist and masterful color painters like Henri Matisse as well as the abstractions of artists like Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky, which characterized the European art scene. In Germany, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, and others politicized their paintings, foreshadowing the coming of World War II, while in America, modernism is seen in the form of American Scene painting and the social realism and regionalism movements that contained both political and social commentary dominated the art world.

Modernism is defined in Latin America by painters Joaquín Torres García from Uruguay and Rufino Tamayo from Mexico, while the muralist movement with Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Pedro Nel Gómez, and Santiago Martinez Delgado, and Symbolist paintings by Frida Kahlo, began a renaissance of the arts for the region, characterized by a freer use of color and an emphasis on political messages. The end of modernism and beginning of postmodernism is a hotly contested issue, though many consider it to have ended roughly around 1940.

Fauvism and Expressionism

Fauvism

The Fauves were a group of early 20th century Modern artists based in Paris whose works challenged Impressionist values.

Key Points

- The Fauvist movement, led by Henri Matisse and Andre Derain, officially lasted for only four years: 1904–1908.

- Vivid color, simplification, abstraction, and unusual brush strokes are hallmarks of the Fauvist style. Fauvist influences and references include Van Gogh’s Post- Impressionism and the Neo-Impressionist technique of Pointillism.

- Gustave Moreau, a controversial professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, mentored several of the Fauves, including Matisse, and profoundly influenced their work.

Key Terms

- Post-Impressionism: (Art) a genre of painting that rejected the naturalism of impressionism, using color and form in more expressive manners.

- pointillism: In art, the use of small areas of color to construct an image.

- Fauvism: An artistic movement of the last part of the 19th century that emphasized spontaneity and the use of extremely bright colors.

Fauvism is the style of les Fauves (French for “the wild beasts”), a short-lived and loose group of early 20th century Modern artists whose works emphasized painterly qualities and strong color over the representational or realistic values retained by Impressionism. While Fauvism as a style began around 1900 and continued beyond 1910, the movement as such lasted only a few years, 1904–1908, and had three exhibitions. The leaders of the movement were Henri Matisse and André Derain.

Apart from Matisse and Derain, other artists included Albert Marquet, Charles Camoin, Louis Valtat, the Belgian painter Henri Evenepoel, Maurice Marinot, Jean Puy, Maurice de Vlaminck, Henri Manguin, Raoul Dufy, Othon Friesz, Georges Rouault, the Dutch painter Kees van Dongen, the Swiss painter Alice Bailly, and Georges Braque (subsequently Picasso’s partner in Cubism).

The paintings of the Fauves were characterized by seemingly wild brushwork and strident colors, while their subject matter had a high degree of simplification and abstraction. Fauvism can be classified as an extreme development of Van Gogh’s Post-Impressionism fused with the pointillism of Seurat and other Neo-Impressionist painters, in particular Paul Signac. Other key influences were Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin, whose employment of areas of saturated color—notably in paintings from Tahiti—strongly influenced Derain’s work.

Derain and Matisse worked together through the summer of 1905 in the Mediterranean village of Collioure, and later that year displayed their highly innovative paintings at the Salon d’Automne. The vivid, unnatural colors led the critic Louis Vauxcelles to derisively dub their works as les Fauves, or “the wild beasts,” which the artists then appropriated as the title for their movement. The painting that was singled out for special condemnation, Matisse’s Woman with a Hat, was subsequently bought by the major patrons of the avant-garde scene in Paris, Gertrude and Leo Stein.

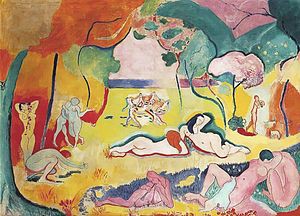

Matisse vied for the title of King of the Avant-garde with Picasso during the first decade or so of the twentieth century. Paintings like Joie de Vivre or Joy of Life had conventional subject matter – a pastorale setting for music, dance, and love – but pictured very differently. He divorces color from form and creates a gentle fantasy that delights the American chemist, businessman, and art collector. His Barnes collection in Philadelphia has many of Matisse’s most formidable works.

“Primitivism” and Cubism

As one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, Pablo Picasso is widely known for his involvement in Cubism and Primitivism.

Key Points

- 1906–1909 is referred to as Picasso’s African period, during which he produced Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and several other paintings incorporating primitivist elements.

- Picasso was inspired by African artifacts as well as the work of Post-Impressionist artist Paul Gauguin.

- The formal elements of Les Desmoisellesd’Avignon bridged Picasso’s African Period and subsequent Cubist work.

- Picasso and Georges Braque co-founded the Cubist movement, one of the most influential movements in Modern Art.

- Cubism stressed basic abstract geometric forms that presented the subject from many angles simultaneously.

Key Terms

- primitivism: Primitivism is a term that borrows visual forms from non-Western or prehistoric peoples, a practice that was central to the development of modern art. Generally considered today to be a colonialist or derogatory way of describing the culture of the other civilizations.

African Period (1906–1910)

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the European cultural elite were discovering African, Micronesian, and Native American art. African artifacts were being brought back to Paris museums following the expansion of the French empire into Africa. The press was abuzz with exaggerated stories of cannibalism and exotic tales about the African kingdom of Dahomey. The mistreatment of Africans in the Belgian Congo was exposed in Joseph Conrad’s popular book, Heart of Darkness.

Artists such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, and Picasso were intrigued and inspired by the stark power and simplicity of styles of “primitive” cultures. Around 1906, Picasso, Matisse, Derain, and other Paris-based artists had acquired an interest in Primitivism, Iberian sculpture, African art, and tribal masks, in part due to the works of Paul Gauguin that had recently achieved recognition in Paris’s avant-garde circles. Gauguin’s powerful posthumous retrospective exhibitions at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1903 and 1906 had a powerful influence on Picasso’s paintings. Picasso created a style of portraiture that seems to have been based, largely, on Iberian masks – appealing because they came from the Iberian, or Spanish and Portuguese, peninsula just as Picasso himself had.

In 1907, Picasso experienced a “revelation” while viewing African art at the ethnographic museum at Palais du Trocadéro. African art influenced Picasso’s painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), especially in its treatment of the two figures on the right side of the composition. This painting is also considered a protocubist work bridging Picasso’s African and Cubist periods.

George Braque was a little older than Picasso. He had been painting in an Impressionist, then Fauvist style. After Cézanne died in 1906, his paintings were exhibited in a large retrospective in 1907. The breaking up of forms into planes of space with brushwork and color greatly influenced Braque. He even painted some of Cézanne’s motifs like the Castle at Roche-Guyon.

Analytic Cubism (1909–1912)

Cubism, established by Picasso and his colleague Georges Braque, was marked by a revolutionary departure from representational art. In Cubist artwork, objects were analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstracted form instead of being depicted from one viewpoint. Picasso, Braque, and other Cubists depicted subjects from a multitude of viewpoints to create a greater scope of context. Cubism has been considered the most influential art movement of the 20th century.

Cubism had a global reach as a movement, influencing similar schools of thought in literature, music, and architecture. Particular offshoots beyond France included the movements of Futurism, Suprematism, Dada, Constructivism, and De Stijl, which all developed in response to Cubism. Early Futurist paintings have some commonalities with Cubism: the fusing of the past and the present and the representation of different views of the subject pictured at the same time, also called multiple perspective, simultaneity or multiplicity. Constructivism was influenced by Picasso’s technique of constructing sculpture from separate elements. Other common threads between these disparate movements include the faceting or simplification of geometric forms, and the association of mechanization and modern life.

The first phase of Cubism is called Analytic Cubism; the multiple perspectives and planes in space in a limited, neutral palette is characteristic of this moment.

In Cubist artwork, objects are analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstracted form. Instead of depicting objects from one viewpoint, the artist depicts the subject from a multitude of viewpoints to represent the subject in a greater context.

Synthetic Cubism (1912-14)

The second phase of Cubism from about 1912 – 1914 is called Synthetic Cubism. It features papier collé, or cut paper collage, as well as Analytic Cubist painting. Braque is credited with the first of these collage/paintings, but Picasso wasn’t far behind. In his Still Life with Chair Caning, commercially printed oilcloth creates the “seat” of the chair and the objects on a café tabletop are painted. The scalloped edge of the table is created from rope with an invisible join!

Futurism

Futurism was an Italian movement that emphasized and glorified themes associated with contemporary concepts of the future such as speed, technology, youth, and violence, as well as objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city. In 1910 and 1911 futurist painters made use of the technique of divisionism, which entails breaking light and color down into a field of stippled dots and stripes. Severini was the first to come into contact with Cubism. Following a visit to Paris in 1911, the Futurist painters adopted the methods of the Cubists. Cubism offered them a means of analyzing energy in paintings and visually expressing their desired focus on dynamism, motion, and speed. The adoption of Cubism determined the style of much subsequent Futurist painting.

Futurism as a movement didn’t survive WWI. After witnessing the carnage machines enacted on the human body in that war the idealistic concept of progress by way of technology was diminished in Europe.

German Expressionism

German Expressionism refers to a number of related creative movements beginning before WWI and peaking in Berlin during the 1920s.

Key Points

- Kathe Kollwitz and are among the independent German Expressionists who were unaffiliated with other Expressionist groups but nonetheless successful.

- Kollwitz is best remembered for her compassionate series, The Weavers.

- Many of Egon Schiele’s contemporaries found the explicit sexual themes of his work disturbing.

- Paula Modersohn-Becker is among the first recognized female artists to create nude self-portraits.

Key Terms

- Weimar Republic: The democratic regime of Germany from 1919 to the assumption of power by Adolf Hitler in 1933.

- expressionism: A movement in the arts in which the artist does not depict objective reality, but rather a subjective expression of inner experience.

- Fauvism: An artistic movement of the last part of the 19th century that emphasized spontaneity and the use of extremely bright colors.

Expressionism

Expressionism was a modernist movement, beginning with poetry and painting, that originated in Germany at the start of the 20th century. It emphasized subjective experience, manipulating perspective for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas. Expressionist artists sought to express meaning or emotional experience rather than physical reality.

Expressionism was developed as an avant-garde style before the First World War and remained popular during the Weimar Republic, particularly in Berlin. The style extended to a wide range of the arts, including painting, literature, theatre, dance, film, architecture, and music.

Expressionist painters had many influences, among them Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, and several African artists. They were also aware of the Fauvist movement in Paris, which influenced Expressionism’s tendency toward arbitrary colors and jarring compositions.

Kathe Kollwitz

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) was a German painter, printmaker, and sculptor whose work offered an eloquent and often searing account of the human condition, and the tragedy of war, in the first half of the 20th century. Initially, her work was grounded in Naturalism, and later took on Expressionistic qualities. Inspired by a performance of Gerhart Hauptmann’s The Weavers, which dramatized the oppression of the Silesian weavers in Langembielau and their failed revolt in 1842, Kollwitz produced a cycle of six works on the Weavers theme. Rather than a literal illustration of the drama, the works were a free and naturalistic expression of the workers’ misery, hope, courage, and, eventually, doom. The Weavers became Kollwitz’ most widely acclaimed work.

Influence of Cubism

Cubist sculpture developed in parallel with Cubist painting, centered in Paris beginning around 1909 and evolving through the early 1920s. The style is most closely associated with the formal experiments of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. Others were quick to follow Braque and Picasso’s lead in Paris, including Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky, Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Laurens, and Ossip Zadkine.

During his period of Cubist innovation, Picasso revolutionized the art of sculpture by combining disparate objects and materials into one sculptural work—the sculptural equivalent of collage in two dimensional art. Just as collage was a radical development in two dimensional art, so was Cubist construction a radical development in three dimensional sculpture.

Dada and Surrealism

Dada and Surrealism were multidisciplinary cultural movements of the European avant-garde that emerged in Zurich and Paris respectively during the time of WWI.

Key Points

- Dada was a political movement opposed to artistic and social conformity as well as the capitalist forces that led to WWI.

- Dada artists worked in non-traditional media including collage, photomontage, and assemblage. Dada artist Michel Duchamp pioneered the notion of the “readymade;” everyday objects appropriated for artistic purposes.

- Dada spread throughout Europe and North America following WWI; by the early 1920s the center of Dada activity was Paris.

- Dada informed many of the major avant-garde movements of the 20th century century, including Surrealism and Social Realism.

- Surrealism began in the 1920s and had a lot in common with Dadaism.

- Surrealist works drew inspiration from intuition, the power of the unconscious mind, and various psychological schools of thought.

- Surrealist artists and writers regarded their work as an expression of the philosophical movement, with the artwork being an artifact.

Key Terms

- readymade: Everyday objects found or purchased and declared art. The readymades of Marcel Duchamp are ordinary manufactured objects that the artist selected and modified as an antidote to what he called “retinal art.” By simply choosing the object (or objects) and repositioning, joining, titling, and signing it, the object became art.

- collage: A composite object or collection (abstract or concrete) created by the assemblage of various media; especially for a work of art like text, film, etc.

- social realism: An artistic movement that depicted social and racial injustice and economic hardship through unvarnished pictures of life’s struggles.

Dada

World War I was a cataclysmic event in Europe. A generation of young men were lost and many countries had their cities and landscapes devastated. The psychic toll on those who endured the war was very great. Artists reacted against the war in a variety of ways, but one of the most influential was the Dada movement.

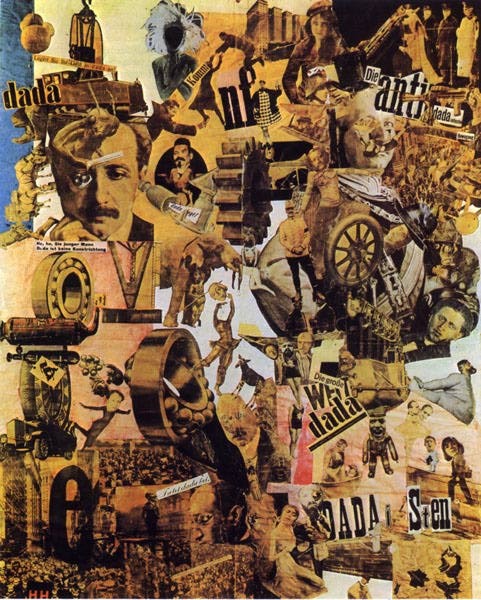

Dada was a multi-disciplinary art movement that rejected the prevailing artistic standards by producing “anti-art” cultural works. Dadaism was intensely anti-war, anti-bourgeois, and held strong political affinities with the radical left. For many participants, the movement was a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests, which many Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity—in art and more broadly in society—that corresponded to the war. Many Dadaists believed that the reason and logic of bourgeois capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expression that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality.

The origin of the name Dada is unclear. Some believe that it is a nonsensical word while others maintain that it originates from the Romanian artists Tristan Tzara’s and Marcel Janco’s frequent use of the words “da, da,” meaning “yes, yes” in Romanian. Another theory posits that the name “Dada” came during a meeting of when a knife stuck into a French–German dictionary happened to point to dada, a French word for “hobbyhorse.” Likely, the origin of the name Dada is another attempt to devalue a system of logic, namely that of language.

Dada began in Zurich, Switzerland, at the Café Voltaire in 1916. Key figures in the Dada movement included Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, Hannah Hoch, and Raoul Hausmann, among others. The movement influenced later styles like avant-garde, and movements including Surrealism, Nouveau réalisme, pop art and Fluxus.

Dada was an informal international movement with participants in Europe and North America that employed all kinds of media but are known especially for collage, writing, photomontage and performance. Dadaists worked in collage, creating compositions by pasting together transportation tickets, maps, plastic wrappers and other artifacts of daily life. Dada artists also worked in photomontage, a variation on collage that utilized actual or reproductions of photographs printed in the press. In Cologne, Max Ernst used photographs taken from the front during World War I to comment on the war. Another variation on collage used by Dadaists was assemblage, the assembly of everyday objects to produce meaningful or meaningless pieces of work, including war objects and trash.

When World War I ended in 1918, most of the Zurich Dadaists returned to their home countries, while some began Dada activities in other cities.

Like Zurich, New York City was a refuge for writers and artists from World War I. Frenchmen Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia met American artist Man Ray in New York City in 1915. The trio soon became the center of radical anti-art activities in the United States.

One of those influenced by Dada’s freedom from constraint in art was Marcel Duchamp who brought some of those ideas to New York with him before WWI. Through his “readymades” – ordinary objects like a bicycle wheel and a wooden stool or the famous urinal that became known as Fountain, 1917 – this repurposing of objects as art introduced very radical ideas about what art could be and who it could be for. Initially an object of scorn within the arts community, the Fountain has since become almost canonized by some as one of the most recognizable modernist works of sculpture. The committee presiding over Britain’s prestigious Turner Prize in 2004, for example, called it “the most influential work of modern art.”

Duchamp’s work would bear fruit in the 1960s and after with the movements of Pop Art, Happenings, Fluxus, and Conceptual Art.

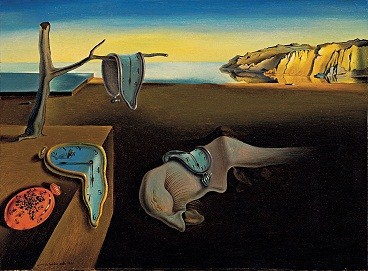

Surrealism

Surrealism was a cultural movement beginning in the 1920s that sprang directly out of Dadaism and overlapped in many senses. Surrealist works drew inspiration from intuition, the power of the unconscious mind, and various psychological schools of thought. The work often features unexpected juxtapositions, non sequiturs, and elements of surprise.

First and foremost, Surrealist artists and writers regarded their work as an expression of the philosophical movement, with the artwork being an artifact. Leader André Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was above all a revolutionary movement. Breton had studied the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud, and his concept of the unconscious became a centerpiece of Surrealist thought. The most important center of the movement was Paris. From the 1920s onward, the movement spread around the globe, eventually affecting the visual arts, literature, film, and music of many countries and languages, as well as political thought and practice, philosophy, and social theory.

As the Surrealists developed their philosophy, they believed that Surrealism would advocate the idea that ordinary and representative expression was vital and important, but that expression must be fully open to the imagination. Freud’s work with free association, dream analysis, and the unconscious was of utmost importance to the Surrealists as they developed methods to liberate their imaginations.

Like Dada, Surrealism aimed to revolutionize human experience, in terms of the personal, cultural, social, and political aspects. Surrealists wanted to free people from false rationality, and also from restrictive customs and structures. Breton proclaimed that the true aim of Surrealism was “long live the social revolution, and it alone!”

Europe from 1920-1945 CE

Soviet Constructivism

Constructivism, an artistic and architectural philosophy that originated in Russia in 1919, rejected the idea of autonomous art.

Key Points

- As much as involving themselves in designs for industry, the Constructivists worked on public festivals and street designs for the post-October revolution Bolshevik government.

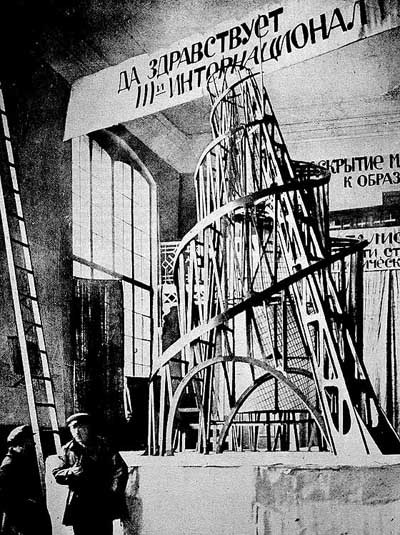

- The canonical work of Constructivism was Vladimir Tatlin’s proposal for the Monument to the Third International (1919), which combined a machine aesthetic with dynamic components celebrating technology such as searchlights and projection screens.

- The First Working Group of Constructivists defined Constructivism as the combination of faktura—the particular material properties of an object—and tektonika, its spatial presence.

Key Terms

- Vladimir Tatlin: (1885–1953) A Russian and Soviet painter and architect. With Kazimir Malevich he was one of the two most important figures in the Russian avant-garde art movement of the 1920s, and he later became an important artist in the Constructivist movement. He is most famous for his attempts to create the giant tower, The Monument to the Third International.

- constructivism: An artistic and architectural philosophy that originated in Russia beginning in 1919, which was a rejection of the idea of autonomous art. The movement was in favor of art as a practice for social purposes. Constructivism had a great effect on modern art movements of the 20th century, influencing major trends such as Bauhaus and the De Stijl movement.

- suprematism: A genre of abstract art based on simple, geometric forms.

Overview

Constructivism was an artistic and architectural philosophy that originated in Russia beginning in 1919. At the heart of the movement was a rejection of the idea of autonomous art. The movement was in favor of art as a practice for social purposes and participation in industry. Constructivism had a considerable effect on modern art movements of the 20th century, influencing major trends such as Bauhaus and the De Stijl movement. Its influence was pervasive, with major impacts upon architecture, graphic and industrial design, theatre, film, dance, fashion, and to some extent music.

Origins and Evolution

The term Construction Art was first used as a derisive term by Kazimir Malevich, an artist of the Suprematist movement, to describe the work of Alexander Rodchenko in 1917. Constructivism as theory and practice was derived largely from a series of debates at INKhUK (Institute of Artistic Culture) in Moscow, from 1920–22. After deposing its first chairman, Wassily Kandinsky, for his “mysticism,” The First Working Group of Constructivists (including Liubov Popova, Alexander Vesnin, Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and the theorists Alexei Gan, Boris Arvatov, and Osip Brik) would develop a definition of Constructivism as the combination of faktura—the particular material properties of an object—and tektonika, its spatial presence. Initially the Constructivists worked on three-dimensional constructions as a means of participating in industry: the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) exhibition showed these three-dimensional compositions by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Karl Ioganson, and the Stenberg Brothers. Later the definition would be extended to designs for two-dimensional works such as books or posters, with montage and factography becoming important concepts.

Public Art

As much as involving themselves in designs for industry, the Constructivists worked on public festivals and street designs for the post-October revolution Bolshevik government. Perhaps the most famous of these was in Vitebsk, where Malevich’s UNOVIS Group painted propaganda plaques and buildings (the best known being El Lissitzky’s 1919 poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge). Inspired by Vladimir Mayakovsky’s declaration “the streets our brushes, the squares our palettes,” artists and designers participated in public life during the Civil War. A striking instance was the proposed festival for the Comintern congress in 1921 by Alexander Vesnin and Liubov Popova, which resembled the constructions of the OBMOKhU exhibition as well as their work for the theater.

There was a great deal of overlap during this period between Constructivism and Proletkult; the ideas of Proletkult concerning the need to create an entirely new culture struck a chord with the Constructivists. In addition, some Constructivists were heavily involved in the “ROSTA Windows,” a Bolshevik public information campaign carried out around 1920. Some of the most famous of these were by the poet-painter Vladimir Mayakovsky and Vladimir Lebedev.

Tatlin’s Vision Versus Gabo’s

The canonical work of Constructivism was Vladimir Tatlin’s proposal for the Monument to the Third International (1919), which combined a machine aesthetic with dynamic components celebrating technology such as searchlights and projection screens. Gabo publicly criticized Tatlin’s design, saying he should “Either create functional houses and bridges or create pure art, not both.” This position had already caused a major controversy in the Moscow group in 1920, when Gabo and Pevsner’s Realistic Manifesto asserted a spiritual core for the movement. This was opposed to the utilitarian and adaptable version of Constructivism held by Tatlin and Rodchenko. Tatlin’s work was immediately hailed by artists in Germany as a revolution in art. A 1920 photograph shows George Grosz and John Heartfield holding a placard saying “Art is Dead–Long Live Tatlin’s Machine Art. ” The designs for the tower were published in Bruno Taut’s magazine Fruhlicht.

Tatlin’s tower started a period of exchange of ideas between Moscow and Berlin, something reinforced by El Lissitzky and Ilya Ehrenburg’s Soviet-German magazine Veshch-Gegenstand-Objet, which spread the idea of “Construction art,” as did the Constructivist exhibits at the 1922 Russische Ausstellung in Berlin, organised by Lissitzky. A “Constructivist international” was formed, which met with Dadaists and De Stijl artists in Germany in 1922. Participants in this short-lived international group included Lissitzky, Hans Richter, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy.

However, the idea of “art” was becoming anathema to the Russian Constructivists. The INKhUK debates of 1920–22 had culminated in the theory of Productivism propounded by Osip Brik and others, which demanded direct participation in industry and the end of easel painting. Tatlin was one of the first to attempt to transfer his talents to industrial production, with his designs for an economical stove, for workers’ overalls, and for furniture. The Utopian element in Constructivism was maintained by his “letatlin,” a flying machine which he worked on until the 1930s.

German Bauhaus Art

The Bauhaus was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts and was famous for its functionalist approach to design.

Key Points

- The Bauhaus had a profound influence on subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography.

- The Bauhaus style was marked by the absence of ornamentation and by harmony between function and overall design.

- The design innovations commonly associated with Gropius and the Bauhaus—radically simplified forms, rationality, functionality, and the idea that mass-production was reconcilable with the individual artistic spirit—were already partly developed in Germany before the Bauhaus was founded.

Key Terms

- Bauhaus: A style in Modernist architecture and modern design, popularized at the “Staatliches Bauhaus” originally in Weimar, Germany.

- Walter Gropius: (1883—1969) A German architect and founder of the Bauhaus School who is widely regarded as one of the pioneering masters of modern architecture.

The Bauhaus was a school in Germany that operated from 1919 to 1933, combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the functional design approach it taught and publicized. Despite its name meaning “house of construction” in German and the founder, Walter Gropius, being an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during its first years. Nonetheless, the school was founded on the idea of “total” creativity, or gesamtkunstwerk, in which all arts would be brought together. Many well-known artists attended the Bauhaus, including Josef Albers, Anni Albers, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Max Bill, and Herbert Bayer. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design, having a profound influence on subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography.

Germany’s defeat in World War I, the fall of the German monarchy, and the abolition of censorship under the new, liberal Weimar Republic allowed an upsurge in artistic experimentation. Many Germans of left-wing views were influenced by the cultural radicalization that followed the Russian Revolution. Yet the political influences can be overstated: Gropius himself did not have radical views and said Bauhaus was entirely apolitical. Another significant influence was the 19th century English designer William Morris, who had argued that art should meet the needs of society and that there should be no distinction between form and function. Thus the Bauhaus style was marked by the absence of ornamentation and by harmony between function and overall design.

The school existed in three German cities: Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932, and Berlin from 1932 to 1933, under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime, having being painted as a centre of communist intellectualism. Although the school was closed, the staff continued to spread its idealistic precepts as they left Germany and emigrated all over the world.

The influence of the Bauhaus on design education was significant. One of the main objectives of the Bauhaus was to unify art, craft, and technology, and this approach was incorporated into the curriculum of the Bauhaus. The structure of the Bauhaus Vorkurs (preliminary course) reflected a pragmatic approach to integrating theory and application. In their first year, students learned the basic elements and principles of design and color theory, and experimented with a range of materials and processes. This approach to design education became a common feature of architectural and design school in many countries.