3.2: Mesopotamia

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 245101

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Art of the Ancient Near East

Cultures in the ancient Near East (often called the Cradle of Civilization) practiced intensive year-round agriculture, developed a writing system, invented the potter’s wheel, created a centralized government, law codes, and empires, and introduced social stratification, slavery, and organized warfare. Societies in the region laid the foundations for astronomy and mathematics.

From Mesopotamia came the empires of Sumeria, Babylon, and Assyria. From the fertile floodplains of the Nile emerged the Egyptians, with their great monuments and sophisticated society. From the Iranian Plateau came the Medes and then the Persians, who nearly succeeded in uniting the entire civilized world under one empire.

In Mesopotamian Babylonia, an abundance of clay and lack of stone led to greater use of mud brick. Babylonian temples were massive structures of crude brick supported by buttresses, with drains to remove rain. The use of brick led to the early development of the pilaster, column, frescoes, and enameled tiles. Walls were brilliantly colored and sometimes plated with zinc or gold, as well as with tiles. Painted terra cotta cones for torches were also embedded in the plaster. In Babylonia, three-dimensional figures often replaced bas-relief—the earliest examples being the Statues of Gudea, which are realistic if somewhat clumsy. The paucity of stone in Babylonia made every pebble precious and led to perfection in the art of gem cutting.

The Mesopotamian Cultures

Sumer was an ancient civilization that saw its artistic styles change throughout different periods in its history.

Key Points

- The Eridu economy produced abundant food, which allowed its inhabitants to settle in one location and form a labor force specializing in diverse arts and crafts.

- Writing produced during the early Sumerian period suggest the abundance of pottery and other artistic traditions.

- Elements of the early Sumerian culture spread through a large area of the Near and Middle East.

- The Sumerian city states rose to power during the prehistorical Ubaid and Uruk periods.

Key Terms

- theocratic: A form of government in which a deity is officially recognized as the civil ruler. Official policy is governed by officials regarded as divinely guided, or is pursuant to the doctrine of a particular religion or religious group.

- casting: A sculptural process in which molten material (usually metal) is poured into a mold, allowed to cool and harden, and become a solid object.

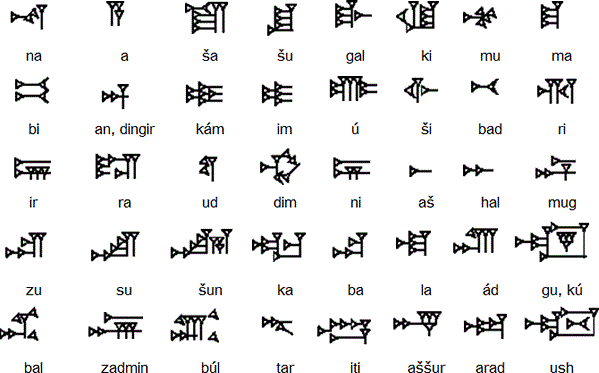

- cuneiform: One of the earliest known forms of written expression that began as a system of pictographs. It emerged in Sumer around the 30th century BC, with predecessors reaching into the late 4th millennium.

Sumer was an ancient civilization in southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) during the Early Bronze Age. Although the historical records in the region do not go back much further than ca. 2900 BCE, modern historians believe that Sumer was first settled between ca. 4500 and 4000 BCE by people who may or may not have spoken the Sumerian language. These people, now called the “Ubaidians,” were the first to drain the marshes for agriculture; develop trade; and establish industries including weaving, leatherwork, metalwork, masonry, and pottery.

The Sumerian city of Eridu, which at that time bordered the Persian Gulf, is believed to be the world’s first city. Here, three separate cultures fused—the peasant Ubaidian farmers, the nomadic Semitic-speaking pastoralists (farmers who raise livestock), and fisher folk. The surplus of storable food created by this economy allowed the region’s population to settle in one place, instead of migrating as hunter-gatherers. It also allowed for a much greater population density, which required an extensive labor force and a division of labor with many specialized arts and crafts.

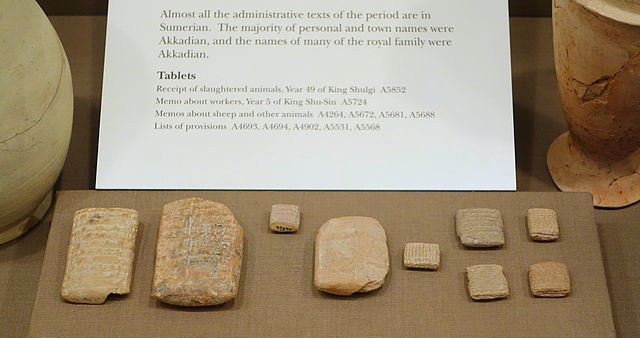

An early form of wedge-shaped writing called cuneiform developed in the early Sumerian period. During this time, cuneiform and pictograms suggest the abundance of pottery and other artistic traditions. In addition to the production of vessels, clay was also used to make tablets for inscribing written documents. Metal also served various purposes during the early Sumerian period. Smiths used a form of casting to create the blades for daggers. On the other hand, softer metals like copper and gold could be hammered into the forms of plates, necklaces, and collars.

Stele of the Vultures

From the Early Dynastic III period (2600-2300 BCE) in what is today Iraq, this stele – usually a vertical commemorative stone – seems to show the victory of the city-state of Lagash over its neighbor, Umma, both Sumerian. Today it exists in fragments in various locations, the one pictured below is in the Louvre. Named for the vultures that appear in one scene, the stele is divided into registers, bands that tell portions of the story. The story is related in cuneiform as well as images.

By the late fourth millennium BCE, Sumer was divided into about a dozen independent city-states delineated by canals and other boundary makers. At each city center stood a temple dedicated to the particular patron god or goddess of the city. Priestly governors ruled over these temples and were intimately tied to the governing of the city-states.

Gilgamesh

The earliest king authenticated through archaeological evidence is Enmebaragesi of Kish, whose name is also mentioned in the Gilgamesh epic (ca. 2100 BCE)—leading to the suggestion that Gilgamesh himself might have been a historical king. As the Epic of Gilgamesh shows, the second millennium BCE was associated with increased violence. Cities became walled and increased in size as undefended villages in southern Mesopotamia disappeared.

Babylonian Empire

One of the most significant developments following the Sumerians was the arrival of the Babylonians by about 1830 BCE. One of the enlightened rulers of this civilization was Hammurabi (ruled c. 1792-1750 BCE) who established the first written code of law. The Stele of Hammurabi is a vertical stone stele inscribed in cuneiform with an entire set of laws that covered everything from inheritance to murder. On top, Hammurabi receives the tools of rulership from his God, Shamash or possibly Marduk. Interestingly, those tools are tools of measurement, as in building, suggesting that the law was seen as measuring out justice.

Sculpture in Mesopotamia

While the purposes that Mesopotamian sculpture served remained relatively unchanged for 2000 years, the methods of conveying those purposes varied greatly over time.

Key Points

- Mesopotamian sculptures were predominantly created for religious and political purposes.

- Common materials included clay, metal, and stone fashioned into reliefs and sculptures in the round.

- The Uruk period marked a development of rich narrative imagery and increasing lifelikeness of human figures.

- Hieratic scale was often used in Mesopotamian sculpture to convey the significance of gods and royalty.

- After the end of the Uruk period, subject matter began to depict scenes of warfare and became increasingly violent and intimidating.

Key Terms

- register: A usually horizontal division of separate scenes in two- or three- dimensional art.

- hieratic scale: A visual method of marking the significance of a figure through its size. The more important a figure is, the larger it appears.

- terra cotta: Clay that has been fired in a kiln.

- high relief: A sculpture that projects significantly from its background, providing deep shadows.

- votive: An object left in temples or other religious locations for a variety of spiritual purposes.

- colossal: Extremely tall.

- lyre: A hand-held stringed instrument resembling a small harp.

- cylinder seal: A small object adorned with carved images of animals, writing, or both, used to sign official documents.

- in the round: Sculpture that stands freely, separate from a background.

- relief: sculpture that projects from a background.

- mixed-media: Artwork consisting of two or more different materials.

- nomadic: Mobile; moving from one place to another, never settling in one location for too long.

The current archaeological record dates sculpture in Mesopotamia the tenth millennium BCE, before the dawn of civilization. Sculptural forms include humans, animals, and cylinder seals with cuneiform writing and imagery in the round or as reliefs. Materials range from terra cotta, stones like alabaster and gypsum, and metals like copper and bronze.

Hunter-Gatherers and Samarra

Because the artists of the hunter-gatherer era were nomadic, the sculptures they produced were small and lightweight. Even after cultures discovered agricultural methods, such as irrigation and animal domestication, artists continued to produce small sculptures. The seated female figure below (c. 6000 BCE), likely carved from a single stone, hails from the prehistoric Samarra culture (5500-4800 BCE). Like many prehistoric female figures, the features of this sculpture suggest that it was used in fertility rituals. Its breasts are accentuated, and its legs are spread in a position that might resemble a woman in labor. While the artist emphasized areas of the body related to reproduction, he or she did not add facial features or feet to the figure.

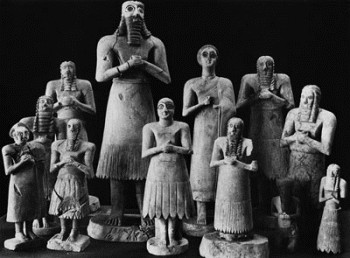

Sculptures in human form were also used as votive offerings in temples. Among the best known are the Tell Asmar Hoard, a group of 12 sculptures in the round depicting worshipers, priests, and gods. Like the cylinder seal found in Queen Puabi’s tomb, the figures in the Tell Asmar Hoard show hieratic scale. Worshipers, as in the image below, stand with their arms in front of their chests and their hands in the position of holding offerings. Materials range from alabaster to limestone to gypsum, depending on each figure’s significance. One common feature is the large hollowed out eye sockets, which were once inlaid with stone to make them appear lifelike. The eyes held spiritual significance, especially that of the gods, which represented awesome otherworldly power.

Akkadian Empire

During the period of the Akkadian Empire (2271-2154 BCE), sculpture of the human form grew increasingly naturalistic, and its subject matter increasingly about politics and warfare.

A cast bronze portrait head believed to be that of King Sargon combines a naturalistic nose and mouth with stylized eyes, eyebrows, hair, and beard. Although the stylized features dominate the sculpture, the level of naturalism was unprecedented. It may have been damaged by subsequent invaders to diminish the power of the previous dynasty. It was stolen during the Iraq War begun in 2003, but returned to the Baghdad Museum.

The Victory Stele of Naram Sin provides an example of the increasingly violent subject matter in Akkadian art, a result of the violent and oppressive climate of the empire. Here, the king is depicted as a divine figure, as signified by his horned helmet. In typical hieratic fashion, Naram Sin appears larger than his soldiers and his enemies. The king stands among dead or dying enemy soldiers as his own troops look on from a lower vantage point. The figures are depicted in high relief to amplify the dramatic significance of the scene. On the right hand side of the stele, cuneiform script provides narration.

Architecture in Mesopotamia

Domestic and public architecture in Mesopotamian cultures differed in relative simplicity and complexity. As time passed, public architecture grew to monumental heights.

Key Points

- Mesopotamian cultures used a variety of building materials. While mud brick is the most common, stone also features as a structural and decorative element.

- The ziggurat marked a major architectural accomplishment for the Sumerians, as well as subsequent Mesopotamian cultures.

- Palaces and other public structures were often decorated with glaze or paint, stones, or reliefs.

- Animals and human-animal hybrids feature in the religions of Mesopotamian cultures and were often used as architectural decoration.

Key Terms

- bas reliefs: Sculptures that minimally project from their backgrounds.

- public sphere: The world outside the home.

- ziggurat: A towering temple, similar to a stepped pyramid, that sat in the center of Mesopotamian city-states in honor to the local pantheon.

- private sphere: The home, or the domestic realm.

- load-bearing: A form of architecture in which the walls are the structure’s main source of support.

- stacking and piling: A form of load-bearing architecture in which the walls are thickest at the base and grow gradually thinner toward the top.

- pilaster: A rectangular column that projects partially from the wall to which it is attached; it gives the appearance of a support, but is only for decoration.

The Mesopotamians regarded “the craft of building” as a divine gift taught to men by the gods, and architecture flourished in the region. A paucity of stone in the region made sun baked bricks and clay the building material of choice. Babylonian architecture featured pilasters and columns, as well as frescoes and enameled tiles. Assyrian architects were strongly influenced by the Babylonian style, but used stone as well as brick in their palaces, which were lined with sculptured and colored slabs of stone instead of being painted. Existing ruins point to load-bearing architecture as the dominant form of building. However, the invention of the round arch in the general area of Mesopotamia influenced the construction of structures like the Ishtar Gate in the sixth century BCE.

Domestic Architecture

Mesopotamian families were responsible for the construction of their own houses. While mud bricks and wooden doors comprised the dominant building materials, reeds were also used in construction. Because houses were load-bearing, doorways were often the only openings. Sumerian culture observed a rigid division between the public sphere and the private sphere, a norm that resulted in a lack of direct view from the street into the home. The sizes of individual houses varied, but the general design consisted of smaller rooms organized around a large central room. To provide a natural cooling effect, courtyards became a common feature in the Ubaid period and persist into the domestic architecture of present-day Iraq.

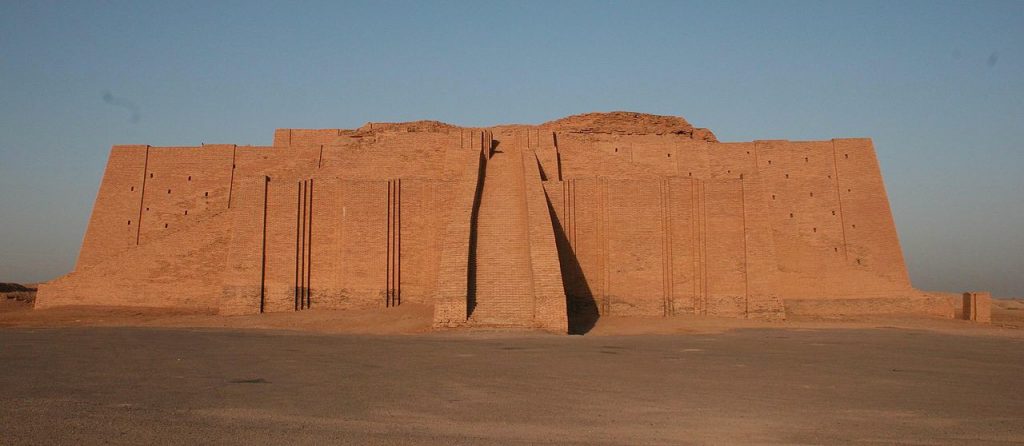

Ziggurats

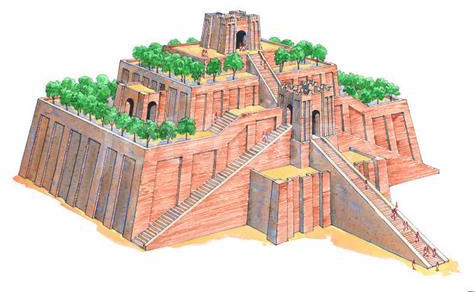

One of the most remarkable achievements of Mesopotamian architecture was the development of the ziggurat, a massive structure taking the form of a terraced step pyramid of successively receding stories or levels, with a shrine or temple at the summit. Like pyramids, ziggurats were built by stacking and piling. Ziggurats were not places of worship for the general public. Rather, only priests or other authorized religious officials were allowed inside to tend to cult statues inside the temple on the top, and make offerings. The first surviving ziggurats date to the Sumerian culture in the fourth millennium BCE, but they continued to be a popular architectural form in the late third and early second millennium BCE as well.

The image below is an artist’s reconstruction of how ziggurats might have looked in their heyday. Human figures appear to illustrate the massive scale of these structures. This impressive height and width would not have been possible without the use of ramps and pulleys. They were part of a larger temple complex with other buildings around them. The primary function seems to have been to elevate the temple and the priest toward their god.

Political Architecture

The exteriors of public structures like temples and palaces featured decorative elements such as bright paint, gold, leaf, and enameling. Some elements, such as colored stones and terra cotta panels, served a twofold purpose of decoration and structural support, which strengthened the buildings and delayed their deterioration.

Between the thirteenth and tenth centuries BCE, the Assyrians replaced sun-baked bricks with more durable stone and masonry. Colored stone and bas reliefs replaced paint as decoration. Art produced under the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE), Sargon II (722-705 BCE), and Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE) inform us that reliefs evolved from simple and vibrant to naturalistic and restrained over this time span.

From the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2350 BCE) to the Assyrian Empire (25th century-612 BCE), palaces grew in size and complexity. However, even early palaces were very large and ornately decorated to distinguish themselves from domestic architecture. Because palaces housed the royal family and everyone who attended to them, palaces were often arranged like small cities, with temples and sanctuaries, as well as locations to inter the dead. As with private homes, courtyards were important features of palaces for both utilitarian and ceremonial purposes.

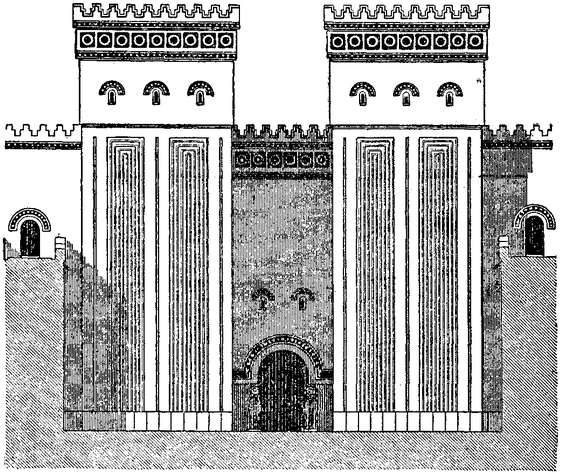

By the time of the Assyrian empire, palaces were decorated with narrative reliefs on the walls and outfitted with their own gates. The gates of the Palace of Dur- Sharrukin, occupied by Sargon II, featured monumental alto reliefs of a mythological guardian figure called a lamassu (also known as a shedu), which had the head of a human, the body of a bull or lion, and enormous wings. Lamassu figure in the visual art and literature from most of the ancient Mesopotamian world, going as far back as ancient Sumer (settled c. 5500 BCE) and standing guard at the palace of Persepolis (550-330 BCE).

Although the Romans often receive credit for the round arch, this structural system actually originated during ancient Mesopotamian times. Where typical load-bearing walls are not strong enough to have many windows or doorways, round arches absorb more pressure, allowing for larger openings and improved airflow. The reconstruction of Dur-Sharrukin (see below) shows that the round arch was being used as entryways by the eighth century BCE.

Perhaps the best known surviving example of a round arch is in the Ishtar Gate, which was part of the Processional Way in the city of Babylon. The gate, now in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, was lavishly decorated with lapis lazuli complemented by blue glazed brick. Elsewhere on the gate and its connecting walls were painted floral motifs and bas reliefs of animals that were sacred to Ishtar, the goddess of fertility and war.

The photograph above shows the immense scale of the gate. The photograph below shows the detail of a relief of a bull, or aurochs, from the gate’s wall. While it is muted in the photo below, the figures are in gold and brown-glazed brick. They symbolized the gods Marduk (dragons), Adad (aurochs or bulls), and Ishtar (lions).

The Assyrian Culture

The Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian capitals of Nimrud, Dur-Sharrukin, and Nineveh are known today for their ruins of great palaces and fortifications.

Key Points

- Nimrud, also known as Kalhu, was the Assyrian capital from the thirteenth century BCE until 706 BCE. Ashurnasirpal II made the city famous when he built a large palace and temples on top of ancient ruins c. 880 BCE.

- Nineveh, the capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, rose to greatness under Sennacherib. He laid out new streets and squares and built within it the famous “palace without a rival”, the plan of which has been mostly recovered.

Key Terms

- Obelisk: A tall, square, tapered, stone monolith topped with a pyramidal point, frequently used as a monument.

- ziggurat: A temple tower of the ancient Mesopotamian valley, having the form of a terraced pyramid of successively receding stories.

Nimrud and Ashurnasirpal II

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located in southern, modern Iraq on the River Tigris. In ancient times the city was called Kalhu. The ruins of the city are found some 30 kilometers (19 miles) southeast of Mosul.

The Assyrian king Shalmaneser I made Nimrud, which existed for about a thousand years, the capital in the thirteenth century BCE. The city gained fame when king Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria (c. 880 BCE) built a large palace and temples on the site of an earlier city that had long fallen into ruins. Nimrud housed as many as 100,000 inhabitants and contained botanic gardens and a zoologic garden. Ashurnasirpal’s son, Shalmaneser III (858–824 BCE), built the monument known as the Great Ziggurat and an associated temple. The palace, restored as a site museum, is one of only two preserved Assyrian palaces in the world. The other is Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh. Nimrud remained the Assyrian capital until 706 BCE when Sargon II moved the capital to Dur-Sharrukin, but it remained a major center and a royal residence until the city was completely destroyed in 612 BCE when Assyria succumbed under the invasion of the Medes.

Excavations at Nimrud in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries revealed remarkable bas- reliefs, ivories, and sculptures. A statue of Ashurnasirpal II was found in an excellent state of preservation, as were colossal winged man-headed lions (Lamassu), each guarding the palace entrance. The large number of inscriptions pertaining to king Ashurnasirpal II provide more details about him and his reign than are known for any other ruler of this epoch.

Portions of the site have been also been identified, such as temples to Ninurta and Enlil, a building assigned to Nabu (the god of writing and the arts), and extensive fortifications. Furthermore, the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, discovered in 1846, stands six-and-a-half-feet tall and commemorates the king’s victorious campaigns from 859–824 BCE. It is shaped like a temple tower at the top, ending in three steps.

Sargon II and Dur-Sharrukin

Dur-Sharrukin, or present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of King Sargon II. Today, Khorsabad is now a village in northern Iraq, and is still inhabited by Assyrians. The construction of Dur-Sharrukin was never finished. Sargon, who ordered the project, was killed during a battle in 705. After his death, his son and successor Sennacherib abandoned the project and relocated the capital with its administration to the city of Nineveh.

Dur-Sharrukin was constructed on a rectangular layout. Its walls were massive, with 157 towers protecting its sides. Seven gates entered the city from all directions. A walled terrace contained temples and the royal palace. The main temples were dedicated to the gods Nabu, Shamash, and Sin, while Adad, Ningal, and Ninurta had smaller shrines. A ziggurat was also constructed at the site. The palace was adorned with sculptures and wall reliefs, with its gates flanked by winged-bull lamassu (or shedu as they are also called) statues weighing up to 40 tons. On the central canal of Sargon’s garden stood a pillared pleasure-pavilion which looked up to a great topographic creation—a man-made Garden Mound. This mound was planted with cedars and cypresses and modeled after the Amanus mountains in northern Syria.

Nineveh

Nineveh was an ancient Assyrian city on the eastern bank of the Tigris River, and the capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Its ruins are across the river from the modern- day major city of Mosul in Iraq.

Today, Nineveh’s location is marked by two large mounds, Kouyunjik and Nabī Yūnus “Prophet Jonah,” and the remains of the city walls. These were fitted with fifteen monumental gateways which served as checkpoints on entering and exiting the ancient city, and were probably also used as barracks and armories. With the inner and outer doors shut, the gateways were virtual fortresses. Five of the gateways have been explored to some extent by archaeologists.

Nineveh was an important junction for commercial routes crossing the Tigris. Occupying a central position on the great highway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean, Nineveh united the East and the West, and received wealth from many sources. Thus, it became one of the oldest and greatest of all the region’s ancient cities, and the capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The area was settled as early as 6000 BCE, and by 3000 BCE had become an important religious center for worship of the Assyrian goddess Ishtar.

It was not until the Neo-Assyrian Empire that Nineveh experienced a considerable architectural expansion. King Sennacherib is credited with making Nineveh a truly magnificent city during his rule (c. 700 BCE). He laid out new streets and squares and built within it the famous “palace without a rival”, the plan of which has been mostly recovered. It comprised at least 80 rooms, many of which were lined with sculpture. A large number of cuneiform tablets were found in the palace. The solid foundation was made out of limestone blocks and mud bricks. Some of the principal doorways were flanked by colossal stone-door figures that included many winged lions or bulls with the heads of men. The stone carvings in the walls include many battle and hunting scenes, as well as depicting Sennacherib’s men parading the spoils of war before him.

Nineveh’s greatness was short-lived. In around 627 BCE, after the death of its last great king Ashurbanipal, the Neo-Assyrian empire began to unravel due to a series of bitter civil wars, and Assyria was attacked by the Babylonians and Medes. From about 616 BCE, in a coalition with the Scythians and Cimmerians, they besieged Nineveh, sacking the town in 612, and later razing it to the ground.

The Assyrian empire as such came to an end by 605 BC, with the Medes and Babylonians dividing its colonies between them. Following its defeat in 612, the site remained largely unoccupied for centuries with only a scattering of Assyrians living amid the ruins until the Sassanian period, although Assyrians continue to live in the surrounding area to this day.

Architecture in Assyria

Assyrian architecture eventually emerged from the shadow of its predecessors to assume distinctive attributes, such as domes and diverse building materials, that set it apart from other political entities.

Key Points

- Inscriptions and reliefs produced under the Assyrian Empire depict structures with octagonal and circular domes, which were unique to the region at the time.

- Assyrian ziggurats eventually consisted of enameled walls and two towers.

- Massive fortified walls are a common attribute in Assyrian fortresses, pointing to the political instability of the time and the need for architectural defense.

- Architectural materials in the Assyrian empire were quite diverse, consisting of a variety of woods, stones, and metals.

Key Terms

- lamassu: A guardian figure consisting of the head of a human, massive wings, and the body of a lion or bull.

During the Assyrian Empire’s historical span from the 25th century BCE to 612 BCE, architectural styles went through noticeable changes. Assyrian architects were initially influenced by previous forms dominant in Sumer and Akkad. However, Assyrian structures eventually evolved into their own unique style.

Temples

Little is known of the construction of Assyrian temples with the exception of the distinctive ziggurats and massive remains at Mugheir. Ziggurats in the Assyrian Empire came to be built with two towers (as opposed to the single central tower of previous styles) and decorated with colored enameled tiles. Contemporaneous inscriptions and reliefs describe and depict structures with octagonal and circular domes, unique architectural systems for the time. Little remains of the temple at Mugheir, but the ruins of its base remain quite impressive, measuring 198 feet (60 m) long by 133 feet (41 m) wide by 70 feet (21 m) high.

Nimrud

Lamassu figures abounded throughout the Assyrian Empire, featuring in the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883-859 BCE) at Nimrud. Reconstructions show that they adorned the gateways of the palace, including an entrance marked by a round arch . According to contemporaneous inscriptions, the palace consisted of wood from a diverse number of tree species, alabaster, limestone, and a variety of precious metals. As with Dur-Sharrukin, the palace of Ashurnasirpal II was surrounded by fortified load-bearing walls.

Artifacts of Assyria

Assyrian artifacts consist of a variety of media and range in size from hand-held to monumental.

Key Points

- The Assyrian Lion Weights and the Statue of Ashurnasirpal II represent rare examples of surviving Assyrian sculpture in the round.

- The Assyrian Lion Weights represent the importance of weights and measures and accommodation of more than one language.

- The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II, the lamassu reliefs, and the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III provide examples of art rich in political and religious symbolism.

- The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II and the lamassu reliefs provide examples of royal hairstyles and beard lengths.

Key Terms

- stylized: Art that is not naturalistic, yet not distorted enough to be abstract.

- sculpture in the round: A free-standing object that is usually meant to be viewed from multiple angles.

- relief: A sculpture that projects from a background.

- Obelisk: Four-sided monument that tapers with height and is usually capped by a pyramidal form.

- register: A usually horizontal band on an artwork that divides designs into logical patterns.

- bas relief: A sculpture with minimal projection from its background.

Artifacts produced during the Assyrian Empire range from hand-held to monumental and consist of a variety of media, from clay to bronze to a diversity of stone. While reliefs comprise the majority of what archaeologists have found, existing sculptures in the round shed light on Assyrian numerical systems and politics.

Assyrian Lion Weights

The Assyrian Lion Weights (800-700 BCE) are a group of solid bronze weights that range from two centimeters (approximately 0.8 inches) to 30 centimeters (approximately 12 inches). Admired as sculptures in the round today, the weights represent one of only two systems of weights and measures in the region at the time. This system was based on heavy mina (about one kilogram) and was used for weighting metals. Additionally, they bear inscriptions in Assyrian cuneiform and Phoenician script, indicating use by speakers of both languages. Eight lions in the set bear the only known inscriptions from the reign of Shalmaneser V (reigned 727-722 BCE).