2: Letters and Rhetoric between East and West (1240s CE)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Western Images of the Mongols: Matthew Paris and Medieval Viral News (1244 CE)

As the expansion of the Mongol empire led to clashes with Latin Christians in eastern Europe and Russia (see chapter one), written reports, diplomats, missionaries, and refugees began to make their way to royal and papal courts as well as to monasteries such as Saint Alban's, which was located along a main road into London. We are fortunate that Saint Alban's possessed an inquisitive chronicler and record-keeper in Matthew Paris. The excerpt translated here represents a tiny fraction of the sources Matthew Paris and others utilized for multiple descriptions of the Mongols and their activities. Matthew’s and others’ depiction of the Mongols (also called Tartars) was also heavily shaped by written and oral reports presented by mendicant missionaries to the council of Lyons (1245), by letters claiming to have been written by the Tartars' ‘‘king’’ (khan), and by letters from displaced rulers and clergymen describing the "invaders" in order to obtain material assistance from western Latin rulers and churches. Matthew Paris was a talented artist, and he accompanied his descriptions of the Mongols with his own drawings, which embody in visual form the dread many western Christians felt.

As Matthew and his audiences sought to make sense of the Mongols' arrival on the world scene, they drew on classical and medieval authors' descriptions of the wondrous peoples and animals said to inhabit the East, including the "monstrous" races whom Alexander the Great was believed to have imprisoned behind the Caspian Gates. These peoples were identified with the description of Gog and Magog in the Apocalypse of John. It was believed that in the last days, they would be freed to ravage the earth in preparation for the arrival of Antichrist. However, there was a more hopeful legend also in circulation, that of the Christian king Prester John, who in a series of fictitious letters composed from the mid-twelfth century onwards (as the medieval equivalent of fake news), was described as living in the Far East and as wishing to ally with western Christian rulers in order to combat various Muslim rulers. The first reports of the Mongols' exploits were forwarded by eastern Christians and merchants and reached crusader armies in Egypt and the Holy Land as reports fostering hopes for assistance from a "King David." These newsletters and prophecies actually combined components of the Prester John legend with accounts of the recent military activities of the Christian Naiman king Küchlüg and/or Činggis Qa’an (Chinggis Khan) and fostered western hopes for a potential alliance with an eastern power against the Muslims.

As further news regarding the Mongols' conquests in Hungary, Poland, the Volga River valley, eastern Germany, Bulgaria, Georgia and Armenia reached Latin Christendom, the "Tartars'" assumed Christianity and usefulness as allies against Muslim rulers was called into doubt. Wave after wave of letters arrived from regions who had been attacked or were believed to be under threat arrived in western Europe. Further news about the "Tartars" was carried by refugees, including dispossessed clergymen and monks, who sought shelter in and assistance from authorities in western Europe. Matthew Paris met one of these displaced persons, who somewhat grandly called himself "Archbishop Peter." Peter may been part of the entourage of the former prince of Kiev, Mikhail of Chernigov, who had been driven into exile when the Mongol occupiers of Kiev granted the rule of the city to the grand duke Vladimir instead. Peter claimed that he was an archbishop with extensive authority within the Russian church and attended the Council of Lyons (1245), which issued a decree urging Christians to fortify their lands in anticipation of a Mongol invasion and also sent out further diplomatic missions to the Mongols. Whether or not we believe Peter's claim to archbishop status, his reports furnished the council, rulers' courts, and Matthew Paris with seemingly eye-witness material of the Mongols' activities in Russia.

Questions to Consider:

Our society is concerned about fake news and news stories going "viral". What agendas and biases appear to shape Matthew Paris' account and that of "Archbishop" Peter?

How are the Mongols (Tartars) represented by Matthew Paris in visual images and in writing? Why are they represented in this way? What is the desired audience response?

Which elements of Mongol society (as described by Matthew Paris) seem to indicate that they might make good allies? Which might make cooperation with Christian rulers difficult?

According to Matthew Paris, how do the Mongols treat their subjects? Why do they treat them this way?

Contemplate the pictures of the Mongols drawn by Matthew Paris. What image of the Mongols is he literally drawing? What details does he use and why are they included? What emotional and political reaction might he have been trying to stir up in whomever saw these drawings (or others like them)?

Make a connection: compare the Mongols' self-presentation in the Secret History (chapter one) with their presentation by Matthew Paris. What elements are the same and what elements are different? What conclusions can we draw about the possible misinterpretation of a society's self-presentation and customs?

Extract from Matthew Paris' English History (1244 CE):

This extract has been adapted by Jessalynn Bird from J. A. Giles' Matthew Paris's English History from the Year 1235 to 1273 (London, 1853), 2:28-31.

A certain archbishop from Russia named Peter, an honorable, devout, and trustworthy man as far as could be judged, was driven from his territory

and his archbishopric by the Tartars [Mongols]. He came into the regions north of the Alps to obtain advice and assistance and comfort in his trouble, if, by the gift of God, the Roman church and the kind favor of the princes of those parts could assist him. When he was questioned about the behavior of the Tartars, as far as he had experienced it [personally], he replied as follows: ‘‘I believe that they are the last of the Midianites, who fled from before the face of Gideon to the most remote parts of the east and the north and took refuge in that place of horror and vast solitude which is called Etren [Judges 7-8]."

They [the Mongols] had twelve leaders, the chief of whom was called the Tartar Khan. From him they take the name of Tartars, although some say they are so called from Tarrachonta, from whom descended Chiarthan, who had three sons, the eldest named Thesir Khan, the second Churi Khan, and the third Bathatar Khan [1]. All of these, although they were born and brought up among the most lofty, and, as it were, impenetrable mountains, as crude, lawless, and inhuman beings educated in caves and dens (after expelling lions and serpents from them), were nonetheless awakened to the allurements of the world. And so the father and sons came forth from their solitudes, armed in their own way, and accompanied by countless hosts of warriors. They laid siege to a city called Ernac, took possession of it, and seized the governor of the city, whom they immediately put to death. When his nephew Cutzeusa, took to flight, they pursued him through several provinces, ravaging the territories of all who sheltered him. Among others, about twenty-six years ago, they devastated a great part of Russia; [2] where they became for a long time shepherds over the flocks they had carried off, and after conquering the neighboring shepherds, they either slaughtered them or reduced them to becoming their subjects.

In this way they [the Mongols] multiplied and became more powerful. Appointing leaders among themselves, they became ambitious for greater things and reduced cities to subjection to them, after conquering their inhabitants. Thesir Khan proceeded against the Babylonians; Churi Khan against the Turks; and Bathatar Khan remained at Ernac, and sent his chiefs against Russia, Poland, Hungary, and several other kingdoms. And [these] three, with their numerous armies, are now presumptuously invading the neighboring provinces of Syria. Twenty-four years, they say, have now gone by since the time when they first came forth from the desert of Etren.

The archbishop, when asked about their mode of [religious] beliefs, replied that they believed there was one ruler of the world; and, when they sent a messenger to the Muscovites [the Kievan Rus], they began it with these words, ‘‘God and his Son in heaven and Chiar Khan on earth.’’ As to their way of life, he said, ‘‘they eat the flesh of horses, dogs, and other unclean meats, and in times of necessity, even human flesh, not raw, however, but cooked. They drink blood, water, and milk. They punish crimes severely, and fornication, theft, lying, and murder with death. They do not reject polygamy, and each man has one or more wives. They do not admit people of other nations to familiar interaction with them or to discuss matters of business or to their secret councils. They pitch their camp apart by themselves and if any foreigner dares to come to it, he is at once killed.’’

With respect to their [religious] rites and superstitions, he said, ‘‘Every morning they raise their hands toward heaven, worshipping their Creator; when they take their meals, they throw the first morsel into the air, and when about to drink, they first pour a portion of the liquor on the ground, in worship of the Creator. They also say that they have John the Baptist for a leader, and they rejoice and observe solemn rituals at the time of the new moon. They are stronger and more nimble than we are, and better able to endure hardships, as also are their horses and flocks and herds. The women are warlike and, above all, are very skillful in the use of bows and arrows. They wear armor made of hides for their protection, which is scarcely penetrable, and they used poisoned iron weapons to attack. They have a great variety of engines, which hurl missiles with great force and straight to the mark. They take their rest in the open air and care nothing for harsh weather."

‘‘They have already enticed numbers of all nations and sects to [join] them, and intend to subjugate the whole world. And they say that it has been indicated to them from heaven that they are to ravage the whole world for thirty-nine years; they assert that the Divine vengeance formerly purged the world by a flood, and now it will be purified by a general depopulation and devastation which they themselves will put into effect. They think and even say that they will have a severe struggle with the Romans, and they call all the Latins Romans. They fear the miracles worked by the church and that the sentence of future condemnation may be passed against them. They declare that, if they can conquer them, they will at once become lords over the whole world. They pay proper respect to treaties in the cases of those who voluntarily give themselves up to them and serve them, selecting the best soldiers from among them, whom, when they are fighting, they always station in front of them. In the same way also they retain among them various workmen. They show no mercy to those who rebel against them, reject the yoke of their domination, or oppose them in the field. They receive messengers with kindness, expedite their business, and send them back [home] again.’’

The archbishop we mentioned was finally asked as to their method of crossing rivers and seas, to which he replied that they cross rivers on horseback or on skins made for that purpose, and that in three places on the seacoast they build ships. He also said that one of the so-called Tartars named Kalaladin, son-in-law of Chiar Khan, who was discovered to have told a lie, was banished to Russia; his life was spared by the Tartar chiefs out of kindness to his wife.

The Mongols as depicted by Matthew Paris, Chronica majora, c. 1250. From Cambridge, Corpus Christi College Library MS 16, fol. 167r. Reproduction courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A Mongol warrior attacks, Matthew Paris, Chronica majora, c. 1250. From Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 016II, fol. 144v. Reproduction courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. For the original, see: https://parker.stanford.edu/parker/c...og/qt808nj0703

Footnotes:

[1] Peter refers here perhaps to Činggis Qa’an (Chinggis Khan), who had four sons by his first wife. Ögӧdei succeeded Chinggis as Great Khan and inherited lands in eastern Asia; Chagatai received central Asia and northern Iran; Jochi, territory conquered in Russia and Ruthenia. Jochi died before his father and so his share was granted to his sons, including Batu. Batu invaded Russia, Poland, and Hungary before returning to eastern Asia after Ögӧdei's death.

[2] This may refer to the Mongols’ devastation of Azerbaijan and Georgia and their defeat of the Cumans and their Russian allies on the river Kalka in 1223.

A Diplomatic Exchange: Innocent IV and the Mongols (1245 CE)

The death of Gregory IX in 1241 and the ongoing struggles between pope and emperor sabotaged plans for an extensive crusade against the Mongols. However, further reports of the Mongols' advance in eastern Europe and the Volga river valley continued to flood Europe (see Matthew Paris above). The Mongols' conquests had also displaced the Khwarizmians, who sacked the holy city of Jerusalem in 1244. In response, Innocent IV called a general council meant to meet in Lyons in 1245 to discuss and suggest solutions to the papal-imperial struggle, assistance for the endangered Latin kingdoms based in the former Byzantine empire and the Holy Land, and the advances of the Mongols. The council at Lyons passed a formal resolution urging Latin Christians to prepare defenses against the "Tartars," and called for a crusade in assistance of the Holy Land.

In an attempt to gather accurate and recent information about the Mongols and the East prior to and immediately after the council of Lyons, Innocent IV turned to the mendicant orders (the Franciscans and Dominicans). Innocent's predecessor as pope, Gregory IX, had already used mendicant friars engaged in missions to eastern Christians to make contact with the Mongol world. This was partly because these friars had the pre-existing contacts, language skills, and geographical knowledge necessary for the task, as well as the zeal to make long and arduous journeys. Innocent IV first sent John of Plano Carpini and Lawrence of Portugal to negotiate with the Mongols in eastern Europe, and Ascelino of Cremona, Simon of Saint Quentin, and Andrew of Longjumeau to negotiate with the Mongols in the Near East. Each group was given papal letters and both missionary and diplomatic agendas. These papal letters were intended for both the Mongols and for eastern Christian churches whom Innocent IV hoped to persuade to accept the authority of the Roman church.

As you will read below, the Mongols were puzzled by the papal letters’ invitation to convert and to cease attacking Christians. Because the Mongols' rulers and generals instead believed in the universal rulership of the Great Khan, they sent back letters with harsh demands. Similar letters were delivered to the Christian prince of the Latin Kingdom of Antioch and to the Christian king of Armenia, demanding monetary tribute and slaves. Partly in order to prevent having to submit to the Turks, the king of Armenia acknowledged Mongol rule instead and refused to send his forces to assist the Latins seeking to protect the Holy Land from the invading Khwarizmians. Despite the discouraging letters brought back by John of Plano Carpini, Innocent IV also sent further missions to the Mongols, including that of the Franciscan William of Rubruck (ca. 1210–ca. 1270). The surviving travelogues of John of Plano Carpini and William of Rubruck provide a uniquely detailed and accurate description of the Mongols and the regions through which the friars traveled.

Pope Innocent IV sends Dominicans and Franciscans out to the Mongols. Master of the Cite des Dames (illuminator), from Vincent of Beauvais, Le Miroir Historial, Vol. 4, Paris, c.1400-1410. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

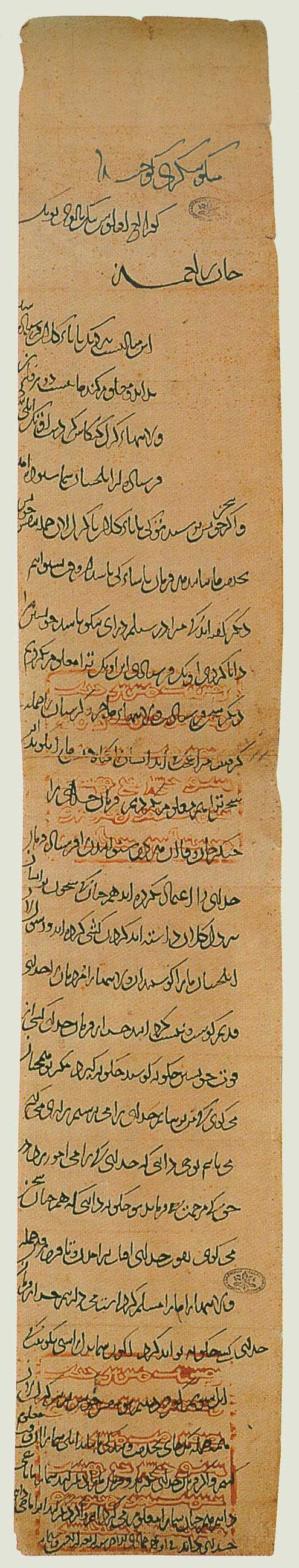

John of Plano Carpini carried at least two letters to the Mongol Khan Güyük. John arrived at the camp of Güyük (near Karakorum) in the summer of 1246 and returned to Lyons by 1247. For an image of how impressive a papal letter would have looked, see this similar surviving letter from Innocent IV. He returned with a letter written in Persian by the scribes of the Great Khan Güyük. All three letters are translated below.

Questions to Consider:

What might have been Güyük’s reaction to Innocent IV's letters?

What does Innocent IV want Güyük to do and why?

What kinds of rhetorical and persuasive techniques does Innocent IV use?

Would the Mongols have found these arguments persuasive? If so, which ones?

How might John of Plano Carpini felt when presenting these letters to the Mongol court?

What might have been the Pope’s reaction to Güyük's letter?

What does Güyük expect the Pope to do and why?

How does Güyük justify the Mongols’ actions?

How does Güyük’s image of the Mongol empire compare to that presented in the other documents you have read?

How does Güyük’s conception of the Yasa [Mongol Law] and the Pax Mongolica compare to the picture of the Mongol empire drawn in your world history textbook?

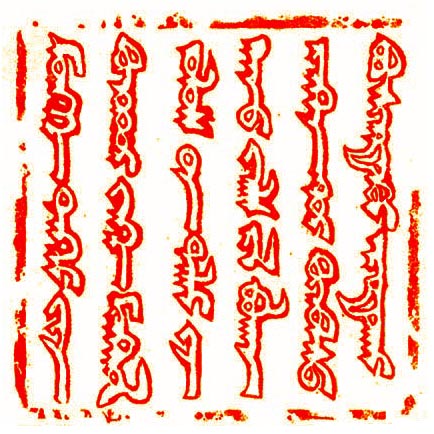

How do both rulers convey their authority in writing? (Consider the pictures of the letters as well as their translations).

A Letter of Innocent IV sent with John of Plano Carpini (dated Lyons, France, March 5, 1245):

God the Father, of His graciousness regarding with unutterable loving-kindness the unhappy lot of the human race, brought low by the guilt of the first man, and desiring of His exceeding great charity mercifully to restore him whom the devil’s envy overthrew by a crafty suggestion, sent from the lofty throne of heaven down to the lowly region of the world His only-begotten Son, consubstantial with Himself, who was conceived by the operation of the Holy Ghost in the womb of a fore-chosen virgin and there clothed in the garb of human flesh, and afterwards proceeding thence by the closed door of His mother’s virginity, He showed Himself in a form visible to all men.

For human nature, being endowed with reason, was meet to be nourished on eternal truth as its choicest food, but, held in mortal chains as a punishment for sin, its powers were thus far reduced that it had to strive to understand the invisible things of reason’s food by means of inferences drawn from visible things. The Creator of that creature became visible, clothed in our flesh, not without change in His nature, in order that, having become visible, He might call back to Himself, the Invisible, those pursuing after visible things, shaping men by His salutary instructions and pointing out to them by means of His teaching the way of perfection: following the pattern of His holy way of life and His words of evangelical instruction, He deigned to suffer death by the torture of the cruel cross, that, by a penal end to His present life, He might make an end of the penalty of eternal death, which the succeeding generations had incurred by the transgression of their first parent, and that man might drink of the sweetness of the life of eternity from the bitter chalice of His death in time. For it behooved the Mediator between us and God to possess both transient mortality and everlasting beatitude, in order that by means of the transient He might be like those doomed to die and might transfer us from among the dead to that which lasts forever.

He therefore offered Himself as a victim for the redemption of mankind and, overthrowing the enemy of its salvation, He snatched it from the shame of servitude to the glory of liberty, and unbarred for it the gate of the heavenly fatherland. Then, rising from the dead and ascending into heaven, He left His vicar on earth, and to him, after he had borne witness to the constancy of his love by the proof of a threefold profession, He committed the care of souls, that he should with watchfulness pay heed to and with heed watch over their salvation, for which He had humbled His high dignity; and He handed to him the keys of the kingdom of heaven by which he and, through him, his successors, were to possess the power of opening and of closing the gate of that kingdom to all. Wherefore we, though unworthy, having become, by the Lord’s disposition, the successor of this vicar, do turn our keen attention, before all else incumbent on us in virtue of our office, to your salvation and that of other men, and on this matter especially do we fix our mind, sedulously keeping watch over it with diligent zeal and zealous diligence, so that we may be able, with the help of God’s grace, to lead those in error into the way of truth and gain all men for Him.

But since we are unable to be present in person in different places at one and the same time for the nature of our human condition does not allow this in order that we may not appear to neglect in any way those absent from us we send to them in our stead prudent and discreet men by whose ministry we carry out the obligation of our apostolic mission to them. It is for this reason that we have thought fit to send to you our beloved son Friar Laurence of Portugal and his companions of the Order of Friars Minor, the bearers of this letter, men remarkable for their religious spirit, comely in their virtue and gifted with a knowledge of Holy Scripture, so that following their salutary instructions you may acknowledge Jesus Christ the very Son of God and worship His glorious name by practicing the Christian religion. We therefore admonish you all, beg and earnestly entreat you to receive these Friars kindly and to treat them in considerate fashion out of reverence for God and for us, indeed as if receiving us in their persons, and to employ unfeigned honesty towards them in respect of those matters of which they will speak to you on our behalf; we also ask that, having treated with them concerning the aforesaid matters to your profit, you will furnish them with a safe-conduct and other necessities on both their outward and return journey, so that they can safely make their way back to our presence when they wish. We have thought fit to send to you the above-mentioned Friars, whom we specially chose out from among others as being men proved by years of regular observance and well versed in Holy Scripture, for we believed they would be of greater help to you, seeing that they follow the humility of our Savior: if we had thought that ecclesiastical prelates or other powerful men would be more profitable and more acceptable to you we would have sent them.

This translation has been transcribed from Christopher Dawson, ed., The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (New York, 1955), pp. 73-75.

A Second Letter from Innocent IV (dated Lyons, France, March 13, 1245):

Seeing that not only men but even irrational animals, nay, the very elements which go to make up the world machine, are united by a certain innate law after the manner of the celestial spirits, all of which God the Creator has divided into choirs in the enduring stability of peaceful order, it is not without cause that we are driven to express in strong terms our amazement that you, as we have heard, have invaded many countries belonging both to Christians and to others and are laying them waste in a horrible desolation, and with a fury still unabated you do not cease from stretching out your destroying hand to more distant lands, but, breaking the bond of natural ties, sparing neither sex nor age, you rage against all indiscriminately with the sword of chastisement.

We, therefore, following the example of the King of Peace, and desiring that all men should live united in concord in the fear of God, do admonish, beg and earnestly beseech all of you that for the future you desist entirely from assaults of this kind and especially from the persecution of Christians, and that after so many and such grievous offenses you conciliate by a fitting penance the wrath of Divine Majesty, which without doubt you have seriously aroused by such provocation; nor should you be emboldened to commit further savagery by the fact that when the sword of your might has raged against other men Almighty God has up to the present allowed various nations to fall before your face; for sometimes He refrains from chastising the proud in this world for the moment, for this reason, that if they neglect to humble themselves of their own accord He may not only no longer put off the punishment of their wickedness in this life but may also take greater vengeance in the world to come.

On this account we have thought fit to send to you our beloved son [John of Plano Carpini] and his companions the bearers of this letter, men remarkable for their religious spirit, comely in their virtue and gifted with a knowledge of Holy Scripture; receive them kindly and treat them with honor out of reverence for God, indeed as if receiving us in their persons, and deal honestly with them in those matters of which they will speak to you on our behalf, and when you have had profitable discussions with them concerning the aforesaid affairs, especially those pertaining to peace, make fully known to us through these same Friars what moved you to destroy other nations and what your intentions are for the future, furnishing them with a safe-conduct and other necessities on both their outward and return journey, so that they can safely make their way back to our presence when they wish.

Translation transcribed from Christopher Dawson, ed., The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (New York, 1955), pp. 75-76.

The Great Khan Güyük’s Reply (in Persian) to Pope Innocent IV (November 3-11, 1246):

Translation copied and modernized from Igor de Rachewiltz, Papal Envoys to the Great Khans (Stanford, 1971), pp. 213-4.

The letter of Güyük to Innocent IV, November 11, 1246, written in Persian with Güyük's seal (stamp), Vatican, Archivio Segreto, Inv. no. A. A., Arm. I-XVIII, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

By the power of the Eternal Sky, the Oceanic Khan of the whole great people, our command.

This is an order sent to the great Pope so that he might know and understand it.

We have written it in the language of the lands of the kerel [perhaps: Latin-speakers].

Counsel was held. A petition of submission was sent; it was heard from your ambassadors.

And if you keep to your word, you, who are the great Pope, together with all the kings, must come in person to do homage to us. We will then cause you to hear every command that there is of the Yasa [Mongol law].

Again. You have said: “Become Christian; it will be good.” You have made yourself wise (or you have been presumptuous). You have sent a petition. This petition of yours we have not understood.

Again. You have sent [these] words: “You have taken all the lands of the Magyars and the Christians. I am astonished. What was their crime? Tell us.” These words of yours we have not understood either. The command of God, Chingiz Khan and Qa’an (Ӧgӧdei), both of them, sent it to cause it to be heard. They have not trusted the command of God. Just like your words, they too have been reckless; they have acted with arrogance; and they killed our ambassadors. The people of those countries, the ancient God killed and destroyed them. Except by God’s command, how should anyone kill, how should [anyone] capture by his own strength?

Do you say, nonetheless: “I am a Christian. I worship God. I despise and ….”? How do you know whom God forgives, to whom he shows mercy? How do you, who say such words, know?

By the power of God [from] the going up of the sun to its going down [God] has delivered all the lands to us. We hold them. Except by the command of God, how can anyone do [anything]? Now you must say with a sincere heart: “We will become [your] subjects; we will give [our] strength.” You in person at the head of the kings, you must all together at once come to do homage to us. We will then recognize your submission. And if you do not accept God’s command and act contrary to our command we will regard you as enemies.

So we inform you. And if you act contrary [to this command], what do we know [of it], it is [only] God [who] knows.

In the last days of Jumada II of the year six hundred and forty-four.

Stamps and Seals: A Comparison

_of_Pope_Innocent_IV._(FindID_134749).jpg?revision=1)

Rachel Atherton, photograph of a lead seal (bulla) of Pope Innocent IV (1243-54), a silken cord would have attached the seal to a papal document. One side bears the inscription "Innocent IV, Pope" in Latin, the other portrays Saints Paul and Peter. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Seal of Güyük Khan using the classical Mongolian script, as found in a letter sent to Pope Innocent IV in 1246. English translation: "Under the Power of the Eternal Heaven, if the Decree of the Oceanic Khan of the Great Mongol Nation reaches people both subject or belligerent, let them revere, let them fear." Literally: "Eternal Heaven's Power-under, Great Mongol Nation's Oceanic Khan's Decree, Subject Belligerent People-unto reach-if, Revere-may Fear-may." Image and caption/translation courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.