1: Apuleius- Cupid and Psyche

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

The Story of Cupid and Psyche from The Golden Ass, by Lucius Apuleius

Edited and translated by John Shinners, converted to LibreText format, footnoted, and enriched with illustrations by Brittany Blagburn and Jessalynn Bird.

1. The Life of Apuleius

Lucius Apuleius (c.125 CE-after 170CE) was born in North Africa (in Maudaura, or modern Mdaurusch, Algeria) to prosperous Berber parents and educated at Carthage, Athens (where he studied Platonic [1] philosophy), and Rome. As a young man, he squandered his inheritance touring Egypt and Asia Minor [2]. During these travels, while he was staying at Oea (modern Tripoli in Libya) in c.156 CE, a student friend convinced Apuleius to marry his widowed mother, Pudentilla, in order to protect her wealth. But the brother of the man previously betrothed to Pudentilla sued Apuleius, accusing him of winning his new wife’s love through magic. He also charged him, among other things, with being obsessed with his mirror and having long hair like a gigolo [3]! Apuleius successfully defended himself in court in his surviving Apologia, a tour de force of rhetoric [4] and wit. But soon afterwards he left Oea for Carthage, where he lived out his life teaching rhetoric and philosophy and gaining enough fame that a statue of him was erected in his honor. Its base still survives, inscribed “To the Platonic philosopher.” Fascinated by Plato, Apuleius wrote two popularizations of his thought: a discussion of Socrates’ [5] inspiring daimonion called The God of Socrates (De deo Socratis) and the (perhaps spurious) Teachings of Plato (De dogmate Platonis). Some of his oratory [6] survives (for instance, an anthology called Florida), but many of his works—including another novel, Hermagoras, and works on astronomy, arithmetic, zoology, arboriculture, medicine, and music—are lost. He died sometime after 170 CE.

The story of Cupid [7] and Psyche [8] is excerpted from his work called Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass (Aureus Asinus), which is the first complete surviving Latin novel, although it is based on a Greek original now lost. Written sometime after 161 CE, the story, told in an ornate Latin style both florid and vivid, concerns Lucius who, burning with curiosity to unlock the secrets of magic while visiting Thessaly in Greece, a region infamous for its sorcery, is accidentally turned into an ass. He endures many picaresque comic misadventures in animal form until the goddess Isis [9] restores his humanity in a mystical finale that reflects Apuleius’s own interest in eastern mystery religions. The tale of Cupid and Psyche (whose name is the Greek word for “soul”) is the most famous story from The Golden Ass, occupying books four through six of the eleven book novel. Within the framework of the novel, Psyche’s curiosity and its disastrous consequences mirror Lucius’s own transmogrifying curiosity. Apuleius’s Cupid and Psyche is probably the inspiration for the fairy tale of “Beauty and the Beast.” Its most famous recent retelling is C. S. Lewis’s novel, Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold (1956).

Fig. 1. A marble statue of Isis, holding a situla and sistrum, ritual implements used in her worship (c.117-138 CE), found at Hadrian's Villa (Pantanello), now at the Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Apuleius's literary description of life as an ass was so convincing that St. Augustine—a fellow North African who extensively cited Apuleius’s God of Socrates in his monumental fifth-century defense of Christianity called The City of God—was unsure whether Lucius’s transformation was “fact or fiction.” In any case, Apuleius’s posthumous reputation as a great magician prompted Augustine to warn his fellow Christians not to think that Apuleius's miracle-working powers were greater than Christ’s. Boccaccio [10] recovered large portions of Apuleius in the fourteenth century and used several of his stories in the Decameron. The Golden Ass was one of the first works of classical Latin literature to be printed (in 1469).

A man feeding a donkey. From Byzantinischer Mosaizist des 5. Jahrhunderts, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Plato was a Greek philosopher from Athens who was a student of Socrates.

[2] Also known as Anatolia, this is the Western peninsula of Turkey.

[3] A young man paid or financially supported by an older woman to be her escort or lover.

[4] The art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing.

[5] Socrates was a Greek philosopher from Athens.

[6] The art of public speaking.

[7] Roman god of love and passion.

[8] Roman goddess of the soul.

[9] Egyptian goddess of magic and life. For the popularity of her cult in the Roman empire, see https://dc.uwm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=rsso

[10] Giovanni Boccaccio was an Italian writer and Renaissance Humanist.

2. The Allegory of “Cupid and Psyche”

For all its many narrative charms, Psyche’s story may also be understood as a Platonic “allegory of the soul’s journey through life and its final union with the divine after suffering and death” (Howatson, 472). Apuleius much admired Plato’s philosophy, and scholars find Platonic themes running throughout The Golden Ass, but especially in the story of Cupid and Psyche. Recall Pausanias’s speech in Plato’s Symposium where he distinguishes between Urania, or Heavenly Venus [1], and Pandemos, or Common Venus. Common Venus represents “the love felt by the vulgar, who are attached . . . more to the body than the soul . . . since all they care about is completing the sexual act” (Symp. 181B). But Heavenly Venus represents something higher—what Diotima in her speech later will call love of the soul. In Apuleius’s "Cupid and Psyche" we clearly see more of Common Venus in Venus' hot-tempered character; in a similar way, we can detect two personalities attached to Cupid (Eros) (Kennedy, 2004, xxv). In relation to most of the other gods—especially his mother, Venus, and Jupiter [2]—he is a mischievous boy (see 5.29-30 and 6.22); but in relation to Psyche he seems much wiser, and more mature and restrained than his young bride. At some moments (e.g., 5.24 & nt. 22), Apuleius even paraphrases Plato to underscore his allegorical intentions.

Though less familiar to us, The Golden Ass also alludes to the cult of the Egyptian goddess Isis [3], who intervenes at the novel’s end to rescue Lucius. Isis was a goddess popular throughout the Mediterranean world by the Hellenistic era [4]. The wife and sister of the god Osiris [5], and the mother of Horus [6], she was a fertility figure initially associated with Ceres [7] but later connected with Venus. By Apuleius’s time, her cult was well-established and celebrated with mystery rituals. In her myth, her husband-brother Osiris was murdered and cut into pieces by his brother, Set [8], a force of evil. Isis gathered the pieces of the slain Osiris who was resurrected but relegated to reign as the god of the Underworld and the dead, but not before he and Isis had conceived their son Horus (the sun god), who ruled the sky. Psyche’s trip into the Underworld presumably reflects this aspect of the legend. Some commentators argue that many other features of her story embody ritual elements of the cult of Isis.

[1] Roman goddess of love and beauty.

[2] Roman king of the gods. God of the sky, lightning, and thunder.

[3] Egyptian goddess of magic and life.

[4] Period between the death of Alexander the Great and the creation of the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean.

[5] Egyptian god of fertility, the afterlife, and the dead.

[6] Egyptian god of the sky.

[7] Roman goddess of the harvest.

[8] Egyptian god of storms, disorder, and violence.

Reading Questions:

1. Bearing in mind that Apuleius has embedded these sorts of allegorical features in “Cupid and Psyche,” keep an eye out for symbolic meanings as you read the story. What point is Apuleius trying to make?

2. Why is Psyche (the soul) in love with Cupid (love), and why does Cupid insist on hiding his appearance?

3. Why is Venus so furious with Psyche? What symbolic meaning might the four tasks she sets for Psyche have?

4. Why is Psyche so curious? Has she progressed from the beginning of the story to its end? If so, what has her journey taught her?

5. What emotions dominate the story? Why?

6. How would Apuleius define love?

7. What picture of stereotypes of and expectations for marriage and relations with in-laws emerge from the stories of Psyche and her sisters?

8. Why might the tale of Cupid and Psyche have been so popular for decorating Greek and Roman sarcophagi?

See the following examples linked below:

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1805-0703-132

https://pigtailsinpaint.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/u-cupid-and-psyche-on-rom.jpg

Cupid and Psyche

The young man, Lucius, has accidentally been turned into an ass and, at this point in his picaresque adventures, is the property of a band of robbers. They bring a young noblewoman to their lair whom they have kidnapped to hold for ransom. Frightened and tearful, she is comforted by an old woman, the robbers’ housekeeper, who tells her the story of Cupid and Psyche to distract her from her troubles:

Book Four

[28] Once there was a king and queen of a certain city. They had three stunningly beautiful daughters, yet as lovely as the two older ones were, it was possible to find words of praise in human speech adequate to their deserts. But the beauty of the youngest girl was so extraordinary that human language was at a loss either to describe it or to praise it sufficiently. Great numbers of its citizens and visitors gathered in multitudes, attracted by the renown of such a marvelous sight. Struck dumb with admiration by her matchless beauty, they touched their right thumb and forefinger together, pressed them to their lips, and venerated her with religious devotion as if she were the goddess Venus [1] herself [2].

Aphrodite Anadyomene. Fresco from Pompei, House of Venus, 1st century AD, by unknown ancient Rome artist, photo of Stephen Haynes, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The news spread through the neighboring cities and nearby regions that the goddess, who was born in the azure depths of the sea and raised by the spray of its foaming waves, had made her divinity visible and dwelled among mortals; or at least that, newly seeded by drops from heaven, the earth—not the sea—had given birth to another Venus in the flower of maidenhood [3].

[29] This unbounded belief grew day by day, and her fame spread to the neighboring islands, then to the mainland, and then to most provinces. Great numbers of mortals made long journeys by land and the deep sea to behold that glorious sign of the times.

No one traveled now to Paphos [4], no one to Cnidus [5], or even to Cythera [6], to gaze thereupon the goddess [7]. Sacrifices at her shrines were ignored; her temples fell into decay; the cushions on which her statues rested were trampled underfoot, her ceremonies neglected; her statues were left without garlands; and her deserted altars were defiled by stone-cold ashes. It was the human girl to whom all prayers were offered up: the divinity of so great a goddess was worshiped in mortal form. When the maiden went out in the morning, the name of the absent Venus was honored with sacrifices and food offerings. When she walked through the streets the people crowded around her, adoring her with garlands and flowers.

The real Venus, seeing that divine honors were being bestowed with such exaggeration on a mortal girl, burned with anger; unable to control her indignation, she shook her head, growled deeply, and said to herself:

[30] “What? Must I, Venus, the ancient mother of nature, the first source of the elements, the nourishment of the whole world, share with a mortal girl the honors due to my divinity? Must my name, held sacred in heaven, be dragged down and profaned by earthly filth? Must I tolerate sharing my divinity in common and the doubts caused by my veneration by proxy? My image is being carried around in a girl born to die. It was pointless for that shepherd, whose just and equitable judgment was confirmed by mighty Jupiter [8], to prefer me, because of my extraordinary beauty, over two mighty goddesses [9]. But this girl who has usurped my honors, whoever she is, won’t be so happy for long. I’ll make her regret her contraband beauty!”

She immediately summons her son [10], that shameless, winged boy whose bad character defies public morality, who wanders around at night armed with torches and arrows [11], going house to house, ruining everyone’s marriage, committing the greatest offenses with impunity, and never doing the least good. Mischievous as he was by his innate rowdiness, she incites him even more by her words [12]. She takes him to the city in question, and points out Psyche [13]—for this was the girl’s name—to him.

Fresco depicting the punishment of Eros by Venus, found in the House of Punished Love in Pompeii, 25 BC, Naples National Archaeological Museum, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

[31] She told him the whole story of how that girl’s beauty rivaled her own. Her indignation found vent in groans of rage: “I beg you,” she said, “by the bonds of a mother’s love, by the sweet wounds made by your arrows, by the burning itch, sweet as honey, of your torch, avenge your mother, avenge her to the fullest measure and severely punish this upstart beauty. I make just one request of you; please grant it: let this maiden be seized with the most burning passion for the lowest kind of man, for a miserable wretch whom Fortune [14] has robbed of social position, inheritance, and even security; for a creature so degraded that his equal cannot be found in the whole world.”

She spoke, and her parted lips lavished long, burning kisses on her son. Then she sought the shore nearby. As her rosy feet touched the tops of the rolling waves, suddenly the deep sea sank back clear and calm. At the first wish that her mind conceived, as if she had given her orders long before, sea deities instantly appeared doing her homage. There were the daughters [15] of Nereus [16], singing in harmony, and Neptune [17] with his bristling, sea-blue beard; Salacia [18], with the folds of her gown laden with fish; little Palæmon [19], riding a dolphin; and bands of Tritons [20] leaping about upon the waves on all sides. One trumpeted softly on a noisy conch shell; another sheltered her with a silken canopy from the blazing heat of her enemy the Sun [21]; another held his mistress’s mirror before her eyes; others, yoked two abreast, swam beneath her chariot. Such was the train that attended Venus when she went to pay a visit to Oceanus [22].

[32] Meanwhile, Psyche, for all her marvelous beauty, reaped no benefit from her looks. Everyone gazed at her, everyone praised her, but no one—neither king, prince, nor commoner—came forward to seek her hand in marriage. People admired her divine beauty, but they all admired it as one admires a beautifully finished statue. Long before, her two older sisters, whose commonplace beauty had stirred no acclaim, had made prosperous marriages with kings. But Psyche, the forlorn virgin, lived with her parents, bewailing her lonely solitude, her body weak, her heart aching. She detested her own beauty, so pleasing to everyone else.

The utterly miserable father of the unhappiest daughter, believing that the gods were angry and fearing their wrath, questioned an ancient oracle [23] of the god who is adored at Miletus [24]. He prayed and offered victims [25] to that powerful divinity on behalf of the untaken virgin; he implored for her marriage and a husband. And Apollo [26]—although he was a Greek and an Ionian [27]—as a courtesy to the author of this Milesian tale, replied with this prophecy in Latin [28]:

On some high mountain’s craggy summit place

The virgin, deck’d for deadly nuptial rites;

Nor hope a son-in-law of mortal race,

But a dire mischief, viperous and fierce;

Who flies through æther [29], and with fire and sword

Tires and debilitates whate’er exists,

Terrific to the powers that reign on high;

E’en mighty Jupiter the wing’d destroyer dreads,

And streams and Stygian [30] shades abhor the pest [31].

The once happy king returned to his palace crushed with discouragement and grief when he had listened to the response of the holy oracle and he explained the command of this ill-omened prophecy to his spouse. There was mourning, weeping, and wailing for several days; but now the hideous fulfillment of this cursed prophecy loomed. The trappings for the most wretched virgin’s funereal wedding were set in place. The marriage torch barely flickers with black soot and ashes; the notes of the nuptial flute change into the plaintive strains of the Lydian mode [32]; the joyous songs of Hymen [33] end in howls of mourning; and the bride wipes her tears away with her very wedding veil [34]. The whole city sighed in sympathy, moved by the fate of the stricken house; and, in keeping with public mourning, all business was immediately declared postponed.

Aldobrandini Wedding Fresco, Vatican Library, depicting Roman Wedding Preparations, unknown artist, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

[34] But the obligation to obey the mandates of the gods summoned the unfortunate Psyche to the punishment appointed to her. With the most intense sorrow, the rites of that funeral marriage are performed, and the living dead is led forth followed by all the people. The weeping Psyche walks not to her wedding but to her funeral. While her grief-stricken parents, overwhelmed by this disaster, shrank from carrying out the terrible deed, their daughter herself encouraged them with these words:

“Why do you distress your unhappy old age with this ceaseless weeping? Why do you wear out your spirit—and mine too—by ceaseless wailing? Why do you distort your features, which I so revere, by fruitless tears? Why, by torturing your own eyes, do you torture mine? Why tear your white hair? Why do you beat your chest and your hallowed breasts? Are these your illustrious rewards for my matchless beauty? You realize too late that it’s cruel Envy [35] that deals you this fatal blow. When the nations and the people offered us divine honors, when with one voice they called me the new Venus—that was when you should have lamented, shed tears, and mourned me as already stricken by death. Now I understand. I see that it is that name of Venus alone that has destroyed me. Lead me to the rock to which Fate [36] has condemned me and leave me there. I am eager to undertake this happy marriage; I am eager to see my noble husband. Why should I delay? Why should I avoid the coming of the one born to be the end of the whole world?”

Edward Burnes-Jones, The Wedding of Psyche, 1895, oil on canvas, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

After she said this, the maiden fell silent and, with unfaltering steps, joined the solemn procession of people accompanying her. They reached the designated cliff: it was a steep mountainside at the top of which they placed the doomed maiden and left her there alone with the nuptial torches which had lighted their way and were now extinguished by their tears. The people returned, with hanging heads, to their homes. As for the wretched parents, overwhelmed by such a terrible calamity, they shut themselves up in the gloom of their shuttered palace and condemned themselves to perpetual night.

Psyche, trembling with terror on the mountaintop, was weeping bitterly when the sweet breeze of softly blowing Zephyr [37] fluttered around the hem of her dress and billowed out its pleats. His tranquil breath gradually lifted her up and carried her leisurely over the slope of the steep cliff; he gently wafted her down into the bosom of the valley below and leaned her back on a flower-strewn bed of turf.

Plate 6: Zephyr carrying Psyche to an enchanted palace, from The Story of Cupid and Psyche as told by Apuleius, Antonio Salamanca, 1530-1560, Public Domain courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

[1] Roman goddess of love and beauty.

[2] The first-century CE Roman natural philosopher, Pliny, reports that this was a typical ritual gesture of worshipers.

[3] The phrase alludes to Hesiod’s version of her birth. When the god Chronos castrated his father, Uranus, he tossed his genitals into the sea; Aphrodite was born from the foam (aphros) they produced. Homer believed she was the daughter of Zeus and Dione.

[4] City on the island of Cyprus.

[5] Greek city in south-western Asia Minor.

[6] Greek island on the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula.

[7] Various myths said she emerged from the sea at Paphos (in Cyprus) or the island of Cythera, where important shrines were built to her. Praxiteles’s famous statue of the naked Venus was at her shrine at Cnidus.

[8] Roman king of the gods. God of the sky, thunder, and lightning.

[9] In the “Judgment of Paris,” Paris, then a shepherd, later prince of Troy, was asked to choose the most beautiful goddess: Hera (Juno), Athena, or Aphrodite (Venus). He picked Aphrodite, who had bribed him with the gift of the most beautiful mortal women, Helen of Troy.

[10] Cupid or Eros (Love).

[11] Cupid had two sets of arrows. Golden arrows that would cause a person to fall in love and lead arrows that would cause a person to be disgusted.

[12] On occasion Apuleius breaks into the present tense.

[13] The Greek word for the soul and also the word for butterfly. In art Psyche is often depicted with butterfly wings.

[14] Greek goddess Tyche.

[15] The Nereids, who numbered fifty to a hundred.

[16] A sea god.

[17] Portunus—properly Portumnus—usually meant Palæmon; here it means Poseidon (Neptune), god of the sea.

[18] Poseidon’s wife, goddess of the sea. Also known as Amphitrite.

[19] A god of the sea who aided sailors in distress alongside his mother. He had been the mortal Melicertes, whom Zeus deified after Hera caused his mother, Ino, and him to drown themselves.

[20] Mermen who were half-men, half-fish. They were the sons of Poseidon and Amphitrite.

[21] The sun is her enemy because her element is water, his fire. It was also the sun, Helios, who told her husband, Hephæstus (Vulcan) about her adultery with Ares (Mars), Odyssey, Bk. VIII. And, as we have seen, well-born women in antiquity valued pale skin untanned by the sun. Throughout this paragraph, Apuleius is showing off his knowledge of myth.

[22] Titan who was the river that encircled the world.

[23] People who interpreted the will of the gods.

[24] Apollo was the patron god of Miletus, a city in Asia Minor.

[25] Animal sacrifices.

[26] Greek god of music, poetry, light, prophecy, and medicine.

[27] Ionia was a region in Asia Minor.

[28] Apollo’s imposing temple at Dydima near Miletus was rivaled only by his shrine at Delphi. Apuleius plays with us here as he breaks into the story to point out why Apollo is speaking in Latin, not Greek. “Milesian Tales” was the name given to the stories of Aristeides of Miletus (2nd century BCE). Stories of love and adventure with vaguely titillating details, they are precisely the kinds of tales Apuleius tells in The Golden Ass. Petronius likewise sprinkles his Satyricon with them. Later authors also use the genre such as Boccaccio in his fourteenth-century Decameron.

[29] According to ancient science, the element that makes up the area in the universe above the terrestrial sphere.

[30] Relating to the river Styx.

[31] This translation is from Thomas Taylor’s 1822 edition of The Golden Ass. In short, Psyche must marry some fierce god that even other gods fear. He is, of course, Cupid, whose love darts even gods can’t avoid, but the prophecy’s ambiguous description makes him sound monstrous.

[32] Ancient music theory assigned different emotions to different modes (or scales). The Lydian mode expressed sorrow.

[33] Greek god of marriage ceremonies.

[34] Apuleius describes details of Roman wedding customs. It was bad luck if the wedding torch smoked or burned out. The howls (the onomatopoeic ululatus in Latin) are the high pitched, rhythmic calls that women in many Mediterranean and Arab countries still make at times of celebration or mourning. The wedding veil (flammeum) was in fact flame-colored, i.e., yellow, reminding us that our western “tradition” of white bridal clothes dates only to the nineteenth century.

[35] Phthonos was the personification of envy and jealousy.

[36] Greek goddesses (Moirai) who determined the destiny of each human.

[37] Greeks and Romans alike personified the winds as gods. We have already met Aeolus, chief god of the winds, in Homer. Boreas was the North Wind, especially venerated by the Greeks; Zephyrus (also called Favonius in Latin) was the West Wind, preferred by the Romans. Depending on who was counting, there were up to eight winds assigned to the various points of the compass.

Book V

[1] As Psyche lay gently upon the soft, grassy bed of dewy green, her great mental distress soothed; she fell sweetly to sleep. Refreshed by slumber, she arose with a more tranquil mind. She saw a grove of huge lofty trees and in its center a spring as clear as crystal. Close beside the gliding spring, there stood a royal dwelling, built by no mortal hands, but by divine skill. From the doorway alone you would know that it was the abode of some deity, so magnificent it was and so pleasing to the eye. The panels of the ceiling, of lemon wood and ivory artfully carved, were supported by golden pillars. All the walls were covered with silver bas-reliefs [1] of beasts wild and tame; these things met the eye as soon as you entered. He must have been a miracle-worker, no a demigod [2], no, rather a veritable god, who could carry subtlety of technique so far and could convert so great a mass of silver into lifelike wild animals. The floor itself was a mosaic of precious stones cut to form many different pictures. (Twice and even more are they truly blessed who walk upon gems and jewelry.) The other parts of that palace stretched far and wide were also priceless beyond measure. The walls, sheathed in solid sheets of gold, shone with a splendor beyond compare; indeed, the rooms, the galleries, the very doors, so flashed and sparkled that the palace would have supplied its own daylight had the sun denied its aid. The rest was on the same scale of magnificence so that it was right to think that mighty Jupiter [3] himself had built that celestial palace in order to live among mortals.

John William Waterhouse, Psyche Opening the Door into Cupid's Garden, Oil on Canvas, 1903, Harris Museum and Art gallery, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

[2] Enchanted by the charm of that beautiful place, Psyche drew nearer, and, growing a little bolder, she crossed the threshold. Soon her pleasure at seeing such beautiful things lured her on, and she looked all about with wondering eyes until, on the far side of the palace, she saw a lofty chamber stuffed with priceless treasure. Nothing wasn’t there. But, amid the wonder caused by such enormous wealth, she marveled most that there was no chain, lock, or guard to defend that treasure house of the world. While she was gazing with infinite pleasure upon all these things, a voice without a body spoke out: “Why, mistress,” it said, “do you marvel at this great wealth? All these things are yours. Go into your chamber and rest from your weariness on the bed; refresh yourself in the bath when it pleases you. We, whose voices you hear, are your servants who will eagerly wait on you. When you have looked after yourself, a royal banquet awaits you.”

[3] Psyche sensed a blessing sent by divine providence; and, heeding the words of the formless voice, first of all she slept and then washed away her weariness with a bath. Suddenly, she saw a semicircular table close beside her; and, judging rightly that it held a meal prepared for her in order to restore her strength, she gladly took her place. In a twinkling, wines like nectar [4] and an abundance of dishes with all sorts of food were placed before her as if wafted there by a breath, for no servant appeared. She could see no one at all; she heard nothing but words falling through the air, and her servants were only voices. After that delicious feast, someone entered and, invisible, began to sing; another played the lyre [5] though it could not be seen; then she heard a great number of voices singing in concert, and although no one was visible, it was evident that there was a large chorus.

[4] After all this entertainment, Psyche, seeing that the day was nearing its close, returned to her room. The night was far advanced when a faint sound caught her ear. Trembling for her virginity since she was so entirely alone, she was oppressed by alarm blended with horror; and, more than all possible harms, she dreaded a danger which she did not know. Her unknown husband [6] approached, climbed into her bed, made Psyche his, and hurriedly departed before sunrise. A moment later, the voices-in-waiting in the chamber tended to the slain virginity of the new bride. This state of affairs continued for a long while. It naturally came about that habit made this new existence sweet to her; and the mysterious voices consoled her in her solitude.

Plate 32- Cupid and Psyche in the nuptial bed, from The Story of Cupid and Psyche as told by Apuleius, Antonio Salamanca, Engraving, 1530-1560, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain, Via Wikimedia Commons.

Meanwhile, her parents grew weary with endless weeping and grief. The news spread abroad, and her two older sisters learned the whole story. Instantly overcome with gloom and grief, they left their homes and rushed to their parents to see them and talk with them.

[5] That same night her husband said this to his Psyche (for though she could not see him, she could touch him and hear his voice): “Sweetest Psyche, my dear wife, Fortune, growing crueler, threatens you with a deadly danger that I urge you to guard against with utmost care. Your sisters, stricken by the thought of your death, are seeking your traces and before long they will reach this cliff. If you chance to hear their weeping, do not reply; do not even look at them. If you do, it will cause the deepest grief to me and terrible disaster for you.” She nodded and solemnly promised that she would follow her husband’s wishes. But as soon as he had disappeared with the night, the poor thing spent the whole day weeping and wailing, repeating again and again that now she really was lost. For, confined in a splendid prison, deprived of human conversation, she could not comfort her grieving sisters or even see them. Spurning bath, food, or anything that would give her strength, she fell to sleep weeping bitterly.

[6] An instant after, her husband came—a little earlier than usual—and lying by her side in the bed, he embraced his still weeping wife and complained: “Is this what my Psyche promised me? Is this what your husband can now expect from you or hope for? All day and all night, even in your husband’s arms, you cling to your pain. Well, now do as you wish and give in to the disastrous demands of your heart. But when you begin to repent too late, remember that I warned you earnestly.” Then, by her pleas and threats of suicide, she forced her husband to agree to her desire to see her sisters in order to soothe their grief and to talk to them. He consented to his new bride’s pleas, and he also permitted her to give them all the gold and jewels she wished. But at the same time he warned her—threatening her again and again—not to follow the evil advice that her sisters might give her about trying to see her husband’s face. Such sacrilegious curiosity would hurl her from the pinnacle of good fortune to ruin, and she would never feel his embraces again. Now much lighter in spirit, she thanked her husband and said to him: “I would rather die a hundred times than abandon this sweetest marriage with you. For I love you passionately, whoever you are; I love you as much as I love my own soul. Cupid himself cannot be compared to you. But, I beg you, grant me one more favor: bid your servant Zephyr [7] to carry my sisters here the same way he brought me.” And, covering him with cajoling kisses, heaping him with honey-sweet words, and entwining him in close embraces, she reinforced her endearments: “My sweet love, husband, your Psyche’s own dear heart!” He reluctantly succumbed to the force and power of her murmurs of love [8] and promised to do all that she asked. With the approach of dawn, he vanished from his wife’s arms.

[7] Meanwhile, her sisters inquired about the location of the cliff where Psyche had been left. They went there with all haste, shed floods of tears, and beat their breasts until the rocks and crags echoed with the sound of their constant wailing. They called out their unfortunate sister’s name again and again until the piercing tones of their shrieking voices spilled down the mountainside and Psyche, in a frenzy of anticipation, rushed from the palace and said: “Why do you needlessly distress yourselves with these woeful lamentations? Here I am for whom you weep. Stop your sad cries; dry your cheeks for so long soaked in tears. Now you can embrace the one for whom you mourned.”

Then she summoned Zephyr and told him of her husband’s commands. Instantly obedient to her order, he wafted them on the gentlest breeze and safely carried them to her. Now they joyfully embraced, hastening to kiss one another; and their tears, which had ceased, fittingly flowed again, stirred up by joy. “Come now,” said Psyche, “enter joyfully this house, our home, and refresh your stricken spirits with your Psyche.”

[8] Having said this, she showed them the vast treasures of that golden palace; she let them hear the chorus of voices at her service; then she splendidly refreshed them with the loveliest bath and the luxuries of a god’s dining table. But now sated by this abundant outpouring of heavenly riches, they began to feed envy deep in their hearts. One of them could not stop asking her very carefully and curiously who was the owner of all these heavenly things, who was her husband, and what sort of creature. But Psyche carefully did not violate her husband’s order or expose her heart’s secrets. Given the situation, she pretended that he was a handsome youth, whose cheeks were just beginning to be shaded with a soft beard, and who passed most of his time in country matters and hunting in the mountains. Then, fearing that if the conversation were prolonged she might slip and betray her secret counsel, she weighed them down with gold and gem-studded jewelry and immediately summoned Zephyr, who carried them back.

[9] This happened instantly. These excellent sisters, as they returned home, were on fire with the swelling poison of envy, and they clamored back and forth: “How blind and cruel and unfair Fortune [9] is. Does it suit you that we, born of the same parents, should bear different destinies? We, who are the oldest, have been married off to foreign husbands to be their serving girls (ancillae). Driven from our home and country, we spend our lives far from our parents, like exiles. Yet our young sister, the last fruit of the fertile soil which her birth exhausted, gets riches such as these and a god for a husband, she who doesn’t even know how to make good use of such an abundance of worldly goods. Did you see, sister, the things scattered about that house? Such jewels, such gorgeous dresses, such gleaming precious gems, and, with all the rest, gold everywhere you walk. If she also has a husband as handsome as she says, there is no one happier now in the whole world. It may well be that, as he comes to know her more [10] and his love increases, her husband, a god, will also make her a goddess. By Hercules [11]! this is already true: she carried herself and acted that way. The woman already has her nose in the air and the airs of a goddess, she who has voices for serving girls and commands the very winds. But I’m miserable whom Fate [12] has given a husband older than my father, balder than a gourd, and as tiny as a boy; and he keeps everything in the palace under lock and key.”

[10] “And I,” replied her sister, “have on my hands a husband all bent and twisted by arthritis, who, for that reason, very rarely gives me any amorous action. I pass almost all my time rubbing his gnarled fingers, hard as any stone, and blistering these dainty hands of mine with smelly ointments, dirty bandages, and reeking poultices. I do not play the obliging role of wife, but ply the backbreaking trade of nurse. You, sister, can see how far you can carry your patience, or, rather—for I’m free to speak my mind—your slavery; for my own part, I can no longer stand the sight of such good fortune fallen to someone unworthy. Remember how proud and arrogant she was with us? Her uncontrolled boasting and showing off revealed her puffed up heart. She reluctantly tossed us some trifles from such a rich store and, quickly bored by our company, she ordered us to be driven out, and, with a puff, we were whistled away. Until I hurl her from such riches into the depths, I’m no woman and I have not a spark of life in me. And if this insult likewise sours you, as it seems, let’s plot some practical plan together. First, we must not show our parents or anyone else the gifts we received; and we must pretend to know nothing about her welfare. It’s quite enough that we’ve seen what we wish we hadn’t without broadcasting to our family and the whole world how fortunate she is; for wealth is not a blessing when no one knows about it. She will learn that we are her older sisters, not her slaves. For the moment, let’s return to our husbands and our poor, if decent, homes; and when we have reflected more deliberately and have made our plans, we will return better prepared to punish such pride.”

[11] Any wicked design could not fail to seem good to those two evil-minded creatures. They concealed all their priceless gifts, and, tearing their hair and their cheeks—they well deserved their pain— they renewed their feigned lamentations. And when they had by this means scratched open again the despairing grief of their parents, they left them abruptly and went to their own homes. There, swollen with rage, they conceived a wicked plot—indeed, a murderous one— against their innocent sister.

Meanwhile, Psyche received further warnings from her unseen husband in their nighttime conversations: “Don’t you see what danger you’re in? Fortune is attacking your outposts. Unless you take strong precautions now, she will soon fight you hand-to-hand. Treacherous she-wolves are straining every nerve to trap you in their wicked snares. Their main goal is to persuade you to see my face; but, as I have often warned you, if you see it, you will not see it. Therefore, if those horrible, blood-sucking witches should return here armed with the most malevolent designs—and return they will, I know—don’t talk to them. If your inborn naivete (genuina simplicitate) and your tender heart (animi tui teneritudine) will not allow you to refuse, at least promise that you will not listen or reply to anything that concerns your husband. For we will soon expand our family, and that womb, until now still a child’s womb, contains another child for us, who will be divine if you hide our secret in silence—but a mortal if you desecrate it.”

[12] This news made Psyche blossom with happiness. She rejoiced in the comfort of having a divine child; she thrilled at the glory of this future promise, and rejoiced at the honor of being called a mother. She anxiously reckoned up the days and months coming and going, and she marveled at the unaccustomed weight increasing little by little in her fertile womb from such a slight prick. But the two deadly and detestable Furies [13], exhaling the poison of vipers, were already hastening toward her with wicked speed. Thus her husband again warned Psyche during his brief visit: “This is the final day; the decisive moment is at hand. An enemy of your own sex and your own blood now takes up its weapons, strikes camp, arrays its battle line, and sounds the charge. Your wicked sisters, sword unsheathed, aim for your throat. Alas, what dire calamities now surround us, sweetest Psyche! Take pity on yourself and on us; by your scrupulous silence, save your home, your husband, yourself, and our little one from the misfortune of the disaster bursting upon us. You can no longer call them sisters, these wicked women who bear you murderous hatred and trample the ties of blood under foot. Do not look at them and do not listen to them when, perched on the cliff like Sirens [14], they make the rocks echo with their ill-omened voices.”

Ulysses mosaic in the Bardo National Museum, Naples, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[13] Psyche replied in a voice broken by tears and sobs: “For a while now, I know, you have tested my loyalty and my discretion; once more again I will prove to you that my heart is firm. But I implore you, order our Zephyr to perform once more his duty; and, since I am forbidden to look upon your divine features, let me at least see my sisters. I beg you, by the waving, fragrant curls of your hair, by your soft, delicate cheeks so like my own, by your breast which burns with an ineffable warmth: as I will at least see your face in our little one, I implore you to yield to my fervent prayers and humble entreaties. Grant me the joy of embracing my sisters, and by that joy refresh the soul of your devoted Psyche. I no longer need to see your face nor will night’s shadows now block the light: I embrace you; you are my light.”

Enchanted by these words and her sweet caresses, her husband wiped away the tears she shed with his own curls and promised to grant her request. A moment later he had disappeared before the approaching dawn.

[14] No sooner had they disembarked, than the two plotting sisters journeyed straightway to the cliff without even paying a visit to their parents. They climbed to the summit with the utmost haste, and, not waiting for the wind to transport them, jumped into space with reckless daring. But Zephyr, mindful of the royal commands, received them, though with regret, in the lap of a current of air and set them softly down upon the ground. Without delay, shoulder to shoulder they made tracks at full speed to the palace. They embraced their poor victim, calling themselves—the liars!—her devoted sisters. Covering the treasury of treachery buried in their hearts with their happy faces, they fawned over her: “Psyche, you’re not the little thing you used to be; now you’re a mother. Do you realize what a treasure for us you’re carrying in that little purse of yours? What a joy to our whole family! How delighted we are! How happy we shall be to raise that golden boy! If his beauty matches his parents’, as it surely will, he will be born a veritable Cupid.”

[15] Thus, by fake affection they gradually possessed themselves of their sister’s mind. She gave them chairs at once to rest from the strains of the journey, ordered hot baths to be prepared for them, and finally ushered them into a superb dining hall where they found the rarest, most marvelous, and daintiest dishes. She ordered a lyre to play: lyre notes sang; a flute: it piped up; she called for a chorus: they sang out; and all this music, performed in their presence by invisible musicians, caressed with sweetest melody the senses of those who heard it. But so wicked and perverse were those two women that this melody, sweet as honey, did not soften or pacify them. Always bent upon ensnaring their sister in their nets, they insidiously steered the conversation, asked her who her husband was, where he was born, what family he came from. Then Psyche, in her extreme simplicity (simplicitate nimia), forgetting what she had said before, concocted a new story. She said that her husband was from a neighboring province; that he had large sums invested in commerce; that he was middle-aged with a sprinkling of white hair. Then, dwelling no further upon that subject, she loaded them again with magnificent gifts and entrusted them to their windy carriage.

[16] But as they were wafted homeward through the air by the gentle breath of Zephyr, they wrangled back and forth: “What are we to think, sister, of that silly creature’s horrible lie? At first her husband was a young man who had no beard except a recent growth of down; now he is a man of middle age whose hair is silvery white. What sort of man is he to have changed so suddenly from youth to old age in so short a time? Sister, there is no other explanation than this: either this awful woman has lied to us or she does not know what her husband’s face looks like. Whichever of these guesses is true, we must strip her of her wealth as soon as possible. If she doesn’t know her husband, it’s certain that she has married a god, and, in that case, her pregnancy means the birth of a god. And as soon as she’s proclaimed the mother of a divine child—Gods forbid!—I shall instantly plait a noose and hang myself. However, let’s return to our parents and spin some lies the same color as hers to agree with what we’ve said.

[17] Thus inflamed by hate, the sisters disdainfully greeted their parents. They were so agitated that they passed the whole night without closing their eyes. In the morning they flew to the cliff and went down straightaway into the valley thanks to the usual assistance of the breeze; and, squeezing their eyelids together to force out a tear, they began their conversation with the girl with these crafty words: “Here you sit happy and content but ignorant of the great horror and unconcerned by the peril threatening you. But we, who with untiring vigilance give all our thoughts to your interests, are deeply tormented by your danger. Truthfully, we’ve learned, beyond the possibility of doubt, a secret that we can’t conceal from you because we share your misfortunes and your grief. It is a huge serpent with countless slinking coils, a neck swollen with deadly poison, and a deep jaw bloody and gaping that lies stealthily by your side at night. Remember the Pythian oracle [15] who declared that you were destined to marry a ferocious beast. Many peasants who have hunted hereabout and most of the people of the neighborhood have seen him returning at night from his feeding grounds and swimming in the shallows of the nearby river

[18] Everyone says that he will not stuff you much longer with so many sweet delicacies. As soon as your unborn child has matured in your womb, he will devour you as a very tasty morsel. Now the decision is yours: whether you will listen to your sisters, who are so concerned for your precious safety, and will fly from death and live with us free from all danger, or whether you prefer to be buried in the belly this most savage beast. But if living in this remote wilderness with your voices, if making secret, filthy, dangerous love, if the embrace of a poisonous serpent delight you, we, in any case, shall have done our duty as faithful and loving sisters.”

Then poor little Psyche, so naive (simplex) and tender of heart, was gripped with sadness by these ghastly words. She put out of mind all her husband’s warnings, forgot the promises she had made to him, and rushed headlong into a bottomless abyss of misfortune. Trembling, her pale face drained of blood, stammering through half-parted lips, she barely gasped to them:

[19] “Dearest sisters, you are loyal to the duties that your affection imposes upon you. I don’t think that those who told you these things are lying. For I have never seen my husband’s face; I have no idea what country he comes from. I have heard him speak only at night, and always in low tones. He conceals his condition from me and never fails to leave me at daybreak. When you say that he is some kind of beast I think you are right. He is particularly intent on always making me fear to see his face and threatens me with the most terrible calamities if I should ever try to look at it. So if it’s in your power to help your poor sister and save her from such a dangerous plight, this is the moment to come to my aid; for to substitute indifference for the foresight you have shown up to this point will destroy all the benefit of that foresight.”

Finding the gates so easily opened and their sister’s heart laid bare before them, those wicked women abandoned their secret weapon in its hiding place and attacked the terrified thoughts of the simple (simplex) girl with the unsheathed sword of deceit.

Plate 12: Psyche's sisters persuade her a serpent is sleeping with her, from The Story of Cupid and Psyche as told by Apuleius, Antonio Salamanca, 1530-1560, Public Domain courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

[20] “Since the ties of blood,” said one of them, “compel us to disregard all danger when your safety is at stake, we will show you your one means of escape, which we have thought about for a long, long time. It is this. Take a keen-edged knife, whet it to an even sharper edge by stropping it gently over your palm, and conceal it in your bed on the side where you usually lie. Get a lamp, fill it full of oil so that it will shine brightly, and place it somewhere behind the bed curtains. Cloak all these preparations in the utmost secrecy. Then, when he has slithered into the room and gotten into bed as usual, when he has stretched himself out and is fast asleep and breathing deeply, slip out of bed, tiptoe barefooted, take the lamp from the dark place where you have hidden it, and use its light to seize the lucky moment to carry out your noble purpose. Grasping the two-edged weapon, boldly raise your right hand high and strike the nape of that terrible serpent’s neck a mighty blow, cutting off his head. Our presence shall not fail you; we will be anxiously waiting and, as soon as you have assured your safety by his death, we will speedily carry you and all this treasure away; then we will marry you, a human being, to a human husband.”

[21] Inflaming with such words the heart of their already thoroughly agitated sister, these two quickly left, fearing to be anywhere near such a crime. The same breeze which had always brought them there bore them to the summit of the cliff and, hurrying away, they boarded their ship and departed.

But Psyche was left alone, except she was not alone because the maddening Furies harassed her; grief washed over her like the waves of the sea. Although her plan was formed and she was determined to carry it out, although her hands were preparing for the crime, still she hesitated. Her resolution was shaken; a thousand conflicting feelings strove for mastery in her heart: she hurries, yet hesitates; she is bold, yet afraid; she is angry, yet despairing; in a word, in one and the same body she hates the beast but loves the husband. But as evening approached and with it the darkness, she hurriedly made everything ready for her shocking crime. Night had come and with it her husband; and, after one skirmish in amorous combat, he had fallen into a deep sleep.

[22] Then Psyche, though weak in both body and spirit, was filled with strength furnished by brutal Fate. She fetched the lamp and grasped the knife; her courage switched her gender. But as soon as the light revealed the secret within the bed, she saw the gentlest of brutes, the sweetest beast: Cupid himself, that beautiful god, gracefully sleeping. At that sight the lamp flickered joyously and the knife repented its impious, sharp edge. As for Psyche, stopped in her tracks at such a sight, she sank to her knees out of her head, faint, deadly pale, and trembling. She sought to hide the weapon, but to hide it by plunging it into her breast; and she would surely have done that had not the blade, in dread of so terrible a crime, slipped from her rash hands and escaped her. And now, though faint and confused, she feels her spirit revive as she continues to gaze upon the beauty of that divine face. She sees the gracious, flowing locks of his golden head seeped in ambrosia [16], his milk-white neck, his rosy cheeks over which fall graceful curls while others cluster about his brow and crown. Their sheen was so brilliant that it made the very rays of the lamp waver. On the flying god’s shoulders gleamed dewy wings of sparkling beauty, and though they were at rest, the delicate down that fringed them kept wantonly quivering. The rest of his body was as smooth and splendid; in short, he was so made that Venus [17] had no cause to regret giving birth to him. At the foot of the bed lay a bow, quiver, and arrows—the mighty god’s benevolent weapons.

Guiseppe Maria Crespi, Cupid and Psyche, 1707-1709, oil on canvas, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

[23] Psyche cannot feast her eyes enough upon them. In her curiosity, she touches, examines, and admires her husband’s weapons; she draws an arrow from the quiver and tests its point upon her fingertip. As she held it, her fingers shook; she grasped it too tightly and pricked herself deeply enough that a drop or two of rosy blood reddened her skin. Thus, unwittingly, Psyche fell in love with Cupid. Burning with ever-growing lust (cupido) for Cupid (Cupido), she leaned over him staring at him with passionate longing; then she smothered him with kisses from her puckered lips parted and full of lust, fearing only that he would awaken too soon. But while she wavered bewildered in her smitten heart, so aroused by such beauty, suddenly, the lamp—was this black treachery, was it poisonous jealousy, or was it that it itched to touch so fair a body and kiss it, as it were?—spurted a drop of scalding oil from its bright flame upon the god’s right shoulder. Rash and insolent lamp! You worthless aide to love. You burned the very god who kindles every flame—you whom some lover first invented so that he could see the one he desired even after night fell. At that burning touch, the god leapt up and, seeing the foul tokens of her broken promise revealed, without a word he flew away from the sight and touch of his most unhappy wife.

Sleeping Eros about to be robbed of his quiver by Psyche. Mosaic rrom Samandağı, third century AD. Antakya Archaeological Museum, Inv. 1021. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[24] But as he rose, Psyche quickly seized his right leg with both hands. A wretched appendage, she hung on to him as he rose higher and flew through the cloudy regions; but, wearied at last, she floated softly to earth [18]. Her godly lover did not abandon her as she lay on the ground, but swooped down to a cypress tree nearby and from its topmost branch spoke to her, deeply angered: “Simple-minded (simplicissima) Psyche, I forgot the commands of my mother, Venus. Instead of addicting you with love for a poor wretch of the basest rank, instead of dooming you, as she ordered me, to the worst marriage, I flew to you as a lover. I acted thoughtlessly in this, I know, and I, the famous archer (sagittarius), wounded myself with my own arrow: I made you my wife. Did I do this so you would think me a beast? So that your knife would cut off my head which holds the eyes that adore you? How often I appealed to your prudence; what kindly counsels I lavished on you! Your excellent advisers will quickly pay for the wicked lessons they have given you. But I shall punish you only by my flight.” Having said this, he stretched out his wings and flew away.

[25] Psyche, lying prone upon the ground, followed her husband’s course as far as her eyes could see him and distressed her heart with the bitterest laments. When his beating wings carried her husband into the heights and out of sight, she ran to the bank of a nearby river and threw herself into it headfirst. But the gentle river—in honor of the god whose habit is to inflame the very waters [19], and moved by fear as well—immediately bore her upon his waves uninjured and laid her on the flower-strewn turf of his bank. It chanced that at that moment Pan [20], the rustic god, was sitting on a low hill close by the river embracing the mountain goddess Echo [21] there on the ground and teaching her to repeat all sorts of pretty little songs [22]. Near the bank, she-goats were frolicking about or browsing upon the grass. The goat-legged god saw the weak and heartsick Psyche, whose misfortune was not unknown to him. Kindly calling her to his side, he comforted her:

“Pretty girl, I’m just a country boy (rusticanus), a goatherd; but, thanks to my great age, I have gained a great deal of experience. Now, if my guess is right—and this is what wise men actually call divination [23]—from your stumbling and often faltering steps, your too pale body, your constant sighs, and your tear-stained eyes, you are totally love-struck. Listen to me: don’t leap off cliffs again or try to kill yourself in any other way. Abandon your sorrow and put away your grief. Instead, worship Cupid, the greatest of gods, with your prayers. Since he’s young, self-indulgent, and wanton, your fawning submission to him will win him over.”

Edward Burne-Jones, Pan and Psyche, 1872-74, oil on canvas, Harvard Art Museums, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

[26] Thus spoke the shepherd god. Psyche made no reply, but venerated his saving power and went her way. After wandering exhausted, she followed an unfamiliar path and came to the city where the husband of one of her sisters reigned. Psyche, having made sure that it was so, asked her presence to be announced to that sister. She was speedily led before her, and after they had exchanged embraces and greetings her sister asked the reason for her visit. She answered: “You remember the counsel that you two gave me: you told me that a beast, masquerading as my husband, passed his nights with me, and you urged me to slay him with a double-edged knife before he could gulp poor me down his greedy jaw. At first I did as we agreed; but when I saw his face by the lamp’s light, I beheld a wonderful and heavenly sight: it was the son, yes, the son, of the goddess Venus; it was Cupid himself lying quietly asleep. Astonished by such a beautiful sight and confused by the cravings of a violent passion, I was at a loss how to control my good fortune. Suddenly—a terrible accident!—the lamp bubbled out a drop of boiling oil upon his shoulder. The pain awoke him instantly and, when he saw me armed with steel and fire, he cried: ‘Your crime is too awful. Leave my bed this instant and take your things with you [24]. Now I will marry your sister’—he mentioned your name—‘in a solemn ceremony.’ And he instantly ordered Zephyr the wind to blow me out of his palace.”

[27] Psyche had barely finished speaking when her sister, aroused by insane desire and wicked jealousy, told her husband a lie concocted on the spot to the effect that she had just learned that her parents were dead, and set sail at once. She hastened at her utmost speed to the cliff and, although a different wind was blowing at the time, blinded by her hopes, she gasped: “Take me, Cupid, take a spouse worthy of you; and you, Zephyr, attend your mistress.” And then, with a great leap, she threw herself off the cliff. But she failed to reach her destination even in death, for the jagged rocks tore her limbs apart and scattered them—just as she deserved—and she perished with her mangled entrails easy fodder for the birds and wild beasts. Nor was the punishment of the second sister long delayed. In due time, Psyche, resuming her wanderings, reached another city where her other sister lived. Seduced by a similar false tale and burning to supplant her younger sister by a criminal marriage, she also hastened to the cliff and fell to her death in the same way.

[28] While Psyche, intent on finding Cupid, wandered over the earth, he, still suffering from the wound inflicted by the lamp, lay groaning in his mother’s bedchamber. But a seagull, that snow-white bird that skims along the surface of the waves brushing them with its wings, plunged down into the ocean’s depths. Landing near lovely Venus who was bathing and swimming, it told her that her son was confined to bed suffering from a severe burn, was grief-stricken, and uncertain of being cured. It said that it had heard from the lips of people everywhere rumors and gossip about the bad deeds of the whole family of Venus: “Cupid is up in the mountains whoring it up, and you, Venus, are amusing yourself by swimming under the sea. Consequently, there is no more pleasure, grace, or charm in life; everything is neglected, gone to seed, and shabby. There are no more marriage bonds, no more mutual friendships, no more affection for children—just enormous squalor and sordid, loathsome matings.” Thus did that talkative and meddling bird chatter in Venus’ ear, tearing her son’s good name to tatters. Consumed with rage, Venus instantly cried out: “So that hopeful son of mine has a girlfriend now? You, who alone serve me lovingly, tell me her name who has seduced a tender and beardless boy. Is it someone from the tribe of nymphs, or from the number of the Seasons, or from the chorus of the Muses, or from my own attendant Graces [25]? The chatty bird, unable to stop talking, said: “Mistress, I’m not quite sure, but if I recall correctly, he has fallen madly in love with a young girl named Psyche.” Indignant, Venus shouted, “What! He really loves that Psyche, the rival for my beauty, who tries to steal my very name? So the little sprout thinks I’m a whorehouse madam (lena)! He only knew about that girl because I pointed her out.”

[29] Screaming this, she rose hurriedly from the sea and hastened to her golden bedchamber. Finding her injured son there just as she had been told, at the very doorway she began bellowing at the top of her lungs: “Well, isn’t this a pretty picture—so becoming to our family tree and your good character! First you trample your mother’s, no, your queen’s, orders underfoot. Why didn’t you soil my rival with a low class love? And at your age—just a boy—you take her in your unrestrained and immature embraces so that I have to endure my enemy as my daughter-in-law. Doubtless you presume, you worthless, unlovable, little seducer, that you are my only noble-born son and that I’m too old to become a mother. But I want you to know that I’ll have another son who will be a much better one than you are. In fact, to make you feel even more shame, I’ll adopt one of my young slaves, and I’ll him give your wings, your torch, your bow, and your arrows; the whole outfit belongs to me, and I didn’t give it to you for you to use it like this. For nothing from your father Vulcan's [26] wealth was used to equip you.

[30] “You’ve been badly raised since you were a baby; you have violent hands and so often you’ve irreverently shot at your elders. You mother-killer; you even strip me bare, your own mother, every day. Haven’t you shot me countless times and ignored me as if I were a widow? You don’t even fear your stepfather, Mars [27], that great and mightiest of warriors. What am I saying? You’re always setting him up with mistresses to my torment. But now I’m going to make you repent for your tricks; you’re going to feel pain and bitterness over this marriage of yours. But what shall I do now that I have become the laughing-stock of the whole world? Where shall I hide my head? How to stop this little lizard? Shall I implore the help of my foe, Sobriety [28] (sobrietas), whom I have so often insulted to gratify my son’s extravagance? Must I seek advice from that coarse woman so careless of how she looks? I shudder at the thought; but revenge has its consolations which should not be scorned. So I must turn to Sobriety and no other. She will thoroughly punish this little fool: she will empty his quiver, blunt his arrows, unstring his bow, and extinguish his torch; and she will restrain his body with the sharpest remedies. I’ll consider this insult atoned for when she has shaved off those shiny golden locks through which I have so often passed my fingers, and when she has clipped those wings which my bosom dyed white from its flowing springs of nectar.”

[31] Having spoken, she rushed furiously forth from her palace, wrath stirring her bile. But she was at once stopped by Juno [29] and Ceres [30]. Those goddesses, seeing her enraged expression, asked why such a savage frown marred the beauty (venustas) of her sparkling eyes. “You have come at the perfect moment to calm the violence burning in my breast,” she said. “I beg you, use all your power to find out for me where that runaway Psyche has fled [31]. For both of you surely are aware of the widespread gossip about my family and the deeds of my son better left unsaid.” Then, aware of these events, they tried to soothe Venus’ fierce wrath: “What, my lady, has your son done so wrong that makes you determined to thwart his pleasure and work to destroy the one he loves? Is it a crime, we ask you, if he takes an eager liking to a pretty girl? You can’t be unaware that he is a man and a young one at that; and surely you haven’t forgotten how old he is? Is it because he wears his years so prettily that he still seems a boy to you? You are a mother and, what is more, a woman of sense; are you always going to take an obsessive interest in his amorous games, hold his excesses against him, disapprove of his lovers, and condemn your own skills and pleasures in that charming boy? What god or mortal will put up with you when you scatter passionate love (cupidines) on people everywhere but forbid the lovers in your own family to love, and shut down the common [32] workshop for women’s weaknesses (vitium)?” Fearing his arrows, the two goddesses thus flattered the absent Cupid with this gracious defense. But Venus, indignant that they were treating the insults she had received as a laughing matter, turned her back on them, and, with rapid steps, went on toward the sea.

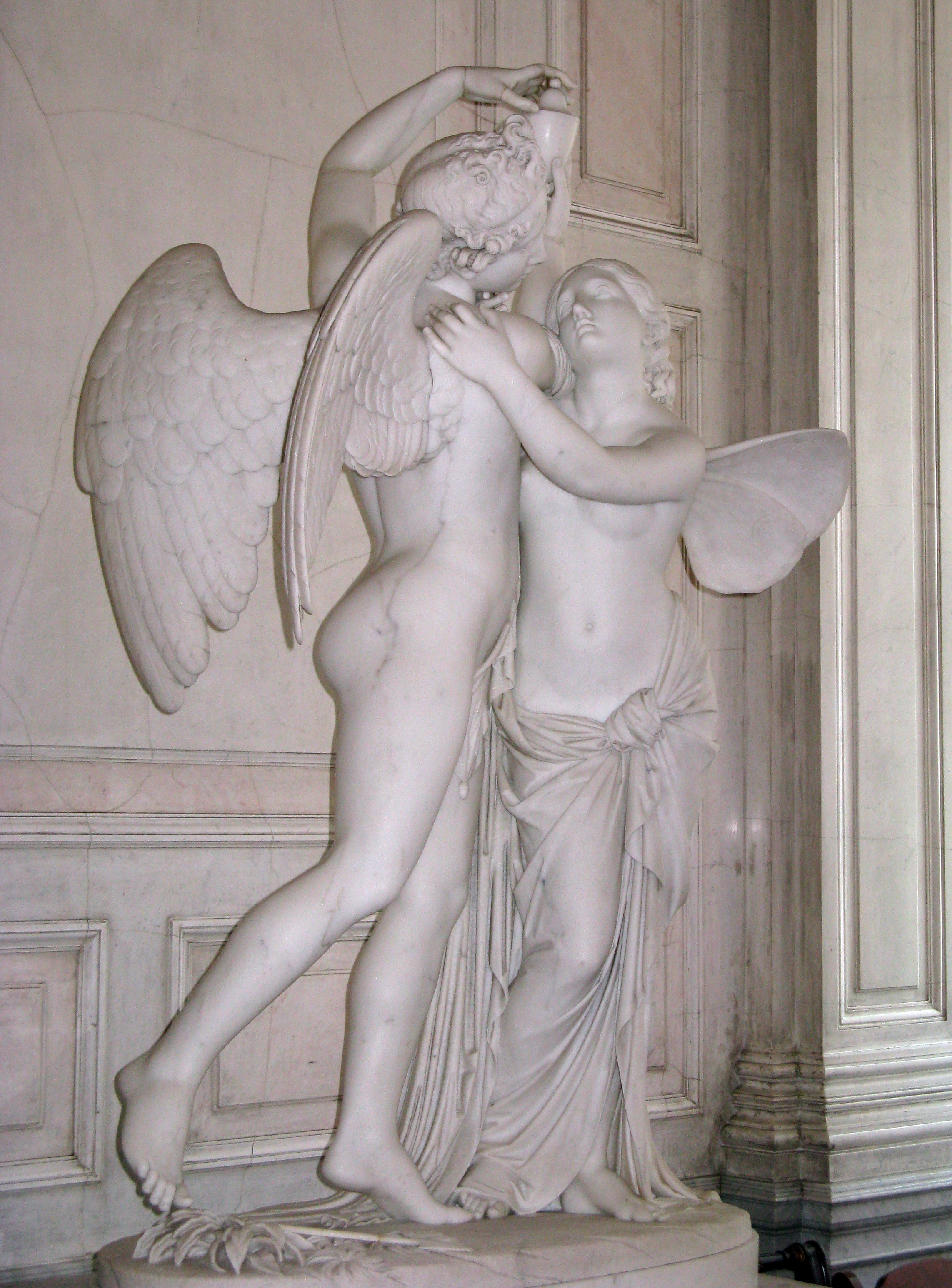

Photograph by Yair Haklai of Giovanni Benzoni's sculpture Cupid and Psyche, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

[1] A relief where the figure slightly protrudes from the background.

[2] Minor deities, often the offspring of a god and a mortal.

[3] God of the sky, thunder, and lightning.

[4] The drink of the gods.

[5] A stringed musical instrument.

[6] "Unknown husband” is “ignobilis maritus.” As well as “unknown,” ignobilis can also mean “low born” or “ignoble,” reminding us that Venus has ordered Cupid to find just such a husband for Psyche.

[7] God of the West wind.

[8] The phrase is “vi ac postestate Venerii,” where Venereus implies sexual love and, obviously, evokes Venus.

[9] Greek goddess Tyche.

[10] The phrase is “procedente consuetudine,” which could also mean “as he has more sex with her.”

[11] Mythological hero known for his strength. Son of Zeus and Alcmene.

[12] Greek goddesses (Moirai) who determined the destiny of each human.

[13] Goddesses of vengeance.

[14] Half bird, half woman creatures who lured sailors to destruction by their voice.

[15] The high priestess serving at the Delphi Temple of Apollo fulfilled the role of oracle and was known as the Pythia.

[16] The food of the gods.

[17] Roman goddess of love and beauty.

[18] Surely a paraphrase of Plato’s Phaedrus, an extensive discussion of the ascent of the soul: “but when, through its inability to follow God, the soul fails to see, and through some mischance is filled with forgetfulness and evil and grows heavy, it loses its wings and falls to the earth” (Ph. 248c).

[19] That is, Cupid’s amorous power also warms sea creatures.

[20] Greek god of the wild, shepherds, and flocks.

[21] A mountain nymph cursed by Hera to only be able to repeat things she had heard.

[22] An odd detail since Echo’s voice, cursed by Hera, could only repeat what was said to it. In one version of her story, Echo spurns Pan’s advances and he orders his followers to tear her to pieces. Apuleius could be suggesting here that Pan is singing to himself and enjoying the effect of an echo/Echo repeating his song—like singing in the shower.

[23] The practice of seeking knowledge of the future or the unknown by supernatural means.

[24] The phrase “Take your things with you” (tibi res tuas habeto), in which a husband returned his wife’s property to her, was the typical formula for making a divorce in ancient Rome.

[25] Nymphs (Greek for “maiden”) were feminine personifications of natural objects like trees and rivers. The Hours were the daughters of Jupiter who regulated the seasons. The nine Muses presided over the various branches of the liberal arts. The Graces were three more daughters of Jupiter (named Aglaia, Euphrosyne, and Thalia) who personified the grace and beauty that make life enjoyable; they usually accompanied the Muses.

[26] Roman god of fire, metalworking, and forges.

[27] Roman god of war.

[28] Greek goddess of restraint.

[29] Roman queen of the Gods, also the goddess of marriage, family, and birth.

[30] Venus is the child of Jupiter and Dione, so Juno, the wife of Jupiter and queen of heaven, is her step-mother. Ceres, the Roman version of Demeter, was the goddess of agriculture, the earth-mother. The sister of Jupiter, she is Venus’ aunt.

[31] "Psychen illam fugitivam” (that runaway Psyche) suggests an escaped slave, a theme that continues throughout the narrative of Psyche’s search for Cupid.

[32] Apuleius may be punning on the double meaning of publica (“common”), which also means “prostitute,” i.e., a “public woman.”

Book VI

[1] Meanwhile, Psyche wandered all about restlessly seeking her husband as her heart’s desire grew ever stronger. However angry he might be, she hoped to appease him, if not by her wifely endearments then at least by slavish pleading. Seeing a temple on the summit of a steep mountain, she said to herself, “How do I know that my lord does not dwell there?” She headed toward the top with quick steps even though she was worn out from her constant wanderings. Hope and her solemn vow spurred her on. When she had bravely climbed to that great height, she entered the sanctuary [1]. She saw sheaves of wheat in great heaps, some of it woven into wreaths, and also ears of barley. There were also scythes and all the implements of harvest; but everything was scattered about in confusion, as happens when careless laborers toss them aside in the heat of summer. Psyche carefully sorted each of these things, arranging them in their proper place. It seemed to her that she should not neglect the shrines and ceremonies of any of the gods but implore the kindly compassion of all of them.

[2] While she performed this task with diligent and conscientious care, Ceres [2] noticed her and called to her from a distance: “Ah, poor Psyche! Venus [3] is furious and painstakingly searching for your tracks over the whole world. She seeks the death penalty for you and exerts all her divine power to be revenged on you. But here you are looking after my things. Are you thinking of everything except your own safety?” Then Psyche dropped to her knees, bathed the goddess’s feet with her abundant tears, swept the ground with her hair, and begged her protection with the most fervent prayers: “By your right hand, which bears the fruits of the earth, by the joyful ceremonies of the harvest, by the secret mysteries of your baskets [4], by the winged chariots of the dragons that serve you, by the furrows of fertile Sicily [5], by the ravisher’s chariot, by the earth which imprisons Proserpine [6], by the subterranean scene of her gloomy wedding, by the torches by whose light you beamed forth from the infernal regions after you had recovered her, and by all the other consecrated mysteries which Eleusis [7], your Attic shrine, veils with an awe-inspiring silence, take under your protection the ill-fated life of Psyche, who kneels suppliantly at your feet [8]. Let me lie hidden for just a few days amid these piles of grain until time calms the fury of that fierce goddess, or at least until a little rest restores my strength, worn out by my toils.”

Edward Burne-Jones, Psyche at the Shrines of Juno and Ceres (Palace Green Murals), Public Domain via Birmingham Museums Trust

[3] Ceres replied: “Your tears and your prayers have touched my heart, and I wish I could help you. But Venus is my kinswoman; the bonds of a longstanding friendship unite us. Furthermore, she is a noblewoman, and I cannot afford to be in her bad graces. So leave this temple immediately, and count yourself lucky that I do not put you under arrest.”

Being thus repulsed contrary to her hope, Psyche went her way and her heart was doubly oppressed. She retraced her steps and saw, in a shadowy wood which lay in the valley, a temple of expert workmanship. Determined to neglect no path to better fortune, no matter how doubtful, and to implore the help of every god, she approached the sacred portals. She saw precious gifts and garments embroidered with gold letters hanging from the branches of the trees and from the doorposts; these recorded the name of the goddess to whom they were offered and thanks for the blessings she bestowed. Then, kneeling and clasping the altar still warm [from sacrifice] with her hands, she offered this prayer after wiping away her tears:

[4] “O sister and spouse [9] of mighty Jupiter [10], whether you abide in your ancient shrine on Samos [11] which glories in your birth cries, your infant wailings, and your upbringing; or whether you dwell in the blessed temple of lofty Carthage [12], which adores you as a virgin coming from heaven riding a lion; or whether you rule over the renowned walls of the Argives [13] near the banks of the Inachus [14], which proclaims you the bride of the Thunderer [i.e., Jupiter] and the queen of the goddesses, may you—whom all the East reveres as Zygia, and all the West, Lucina—be Juno [15] the Savior (Iuno Sospita) [16] to me in my terrible misfortune. Deliver me, worn out from my great toil, from the imminent peril which I fear. For I know that, even unbidden, you help pregnant women in times of danger.” She prayed in this way and Juna instantly appeared before her, in all the imposing majesty of her divinity, and replied: “I truly wish I could answer your prayers. But decency does not allow me to go against the will of Venus, my daughter-in-law, whom I have always loved as my own child. And then there are the laws that forbid me from protecting runaway slaves against their masters’ will [17].”

[5] This latest shipwreck of her fortunes absolutely terrified Psyche. Unable to find her winged spouse and abandoning all hope of safety, she gathered her thoughts: “What aid for my misery can I now seek or hope to obtain when even goddesses, despite their goodwill, cannot help me? Where can I turn now, trapped in such snares? What roof, what darkness even, will conceal me so that I can escape the inescapable eyes of mighty Venus? Now you must take on a manly spirit (masculum animum). Bravely renounce empty hope. Give yourself up voluntarily to your mistress; your submission, though belated, will soften her rage. And who knows, maybe you will find the one you have been seeking for so long in his mother’s house.” Ready for the uncertain result of surrendering— rather, for certain destruction—she considered how she should begin her entreaties.

[6] Meanwhile, Venus, abandoning earthly solutions to her search, headed for heaven. She ordered made ready the chariot that Vulcan [18] the goldsmith had carefully adorned with exquisite artistry and given to her as a wedding gift before their marriage. Where the artist’s file had incised the metal was clearly visible and the result was even more precious than the gold lost through the filing. Four white doves [19] from among the numerous doves nesting about their mistress’s bedroom flew joyously to meet her, and, with a turn of their soft-hued necks, passed their heads through a yoke gleaming with precious stones. Their mistress seated herself and they flew merrily upward. Frisky sparrows [20] chirping boisterously attended the goddess’s chariot; other birds, singing sweetly with soft, honeyed melodies, announced the goddess’s coming. The clouds parted, heaven opened its gates to its daughter, the upper air welcomed the goddess with transports of joy, and the mighty Venus musical escort had no fear of encountering eagles or rapacious vultures [21].

Pietro da Cortona, Charioit of Venus, 1622, Tempera on Canvas, Capitoline Museum, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

[7] Instantly she turned her course toward Jupiter's royal fortress, and, with a haughty petition, demanded the services of Mercury [22], the messenger god (dei vocalis), which were necessary to the success of her plans. Jupiter's dark brow nodded his assent. Triumphant Venus, accompanied by Mercury, once more descended to earth and she earnestly said to him: “My Arcadian [23] brother, you certainly know that your sister Venus has never accomplished anything without the aid of Mercury; you also know how long I’ve been unable to find that female slave hiding from me. There is nothing else to do now except for you, in your office as Junald (praeconium), to proclaim publicly that there will be a reward for the person who finds her. Carry out my request speedily, and clearly point out her distinguishing characteristics so that if anyone is accused of the crime of illegally hiding her, he will not be able to defend himself with ignorance as an excuse.” With that, she gave him a handbill (libellum) containing Psyche’s name and other details, and then at once returned home.

[8] Mercury did not neglect to obey. Dashing about all the nations of the world from one end to the other, he carried out his duty, making this announcement as ordered: “A slave named Psyche, a king’s daughter, and belonging to Venus, has fled from her mistress. Whoever can detain her or point out the place where she lies hidden is requested to give notice to Mercury, who makes this announcement, behind the Murcian Pyramids [24]. He shall receive, by way of reward for his information, seven sweet kisses (savia suavia) from Venus herself, and a last one, even sweeter, with a deep thrust of her honeyed tongue.”