Ahmad ibn Fadlān and the Rūs (Vikings)

- Page ID

- 126796

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Why is Ahmad ibn Fadlān important?

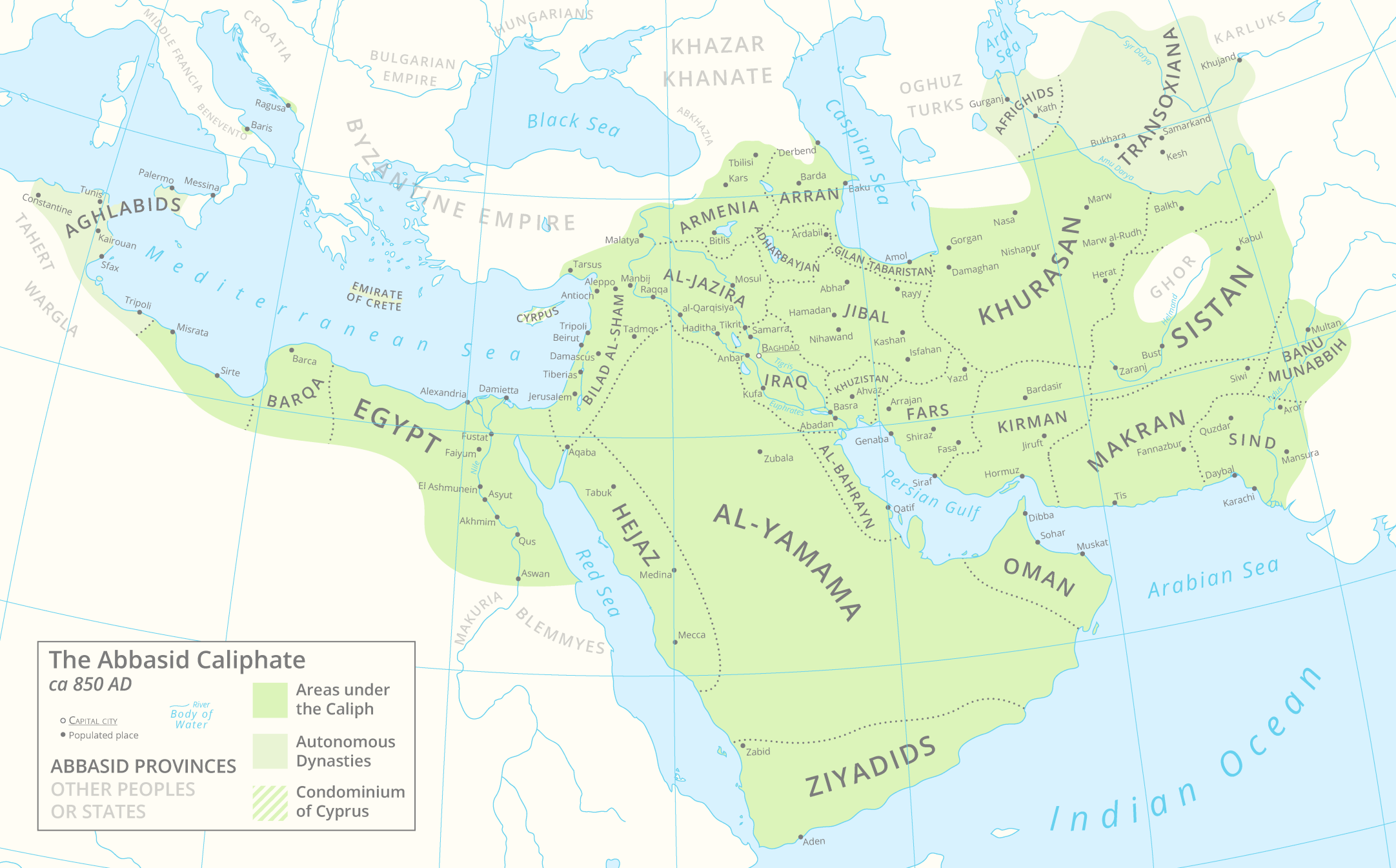

Traditionally, historians have attempted to label the period in which Ahmad ibn Fadlān was writing as the “Dark Ages”. They argued that the disintegration of Charlemagne’s empire, raids by Vikings and other “barbarians,” and the rise of the Islamic Abbasid caliphate meant that Europe became economically and culturally isolated from the Mediterranean world. However, this was not the case, as the Abbasid caliph’s gift of an elephant to Charlemagne proved (the hapless elephant was transported from northern Africa to Italy to be presented to the newly crowned emperor). The Abbasid empire spanned the world from modern-day Spain to India, reinvigorating the global trade networks and establishing new ones.

The Abbasid caliphate at around 850 CE. Courtesy of Cattette at Wikimedia Commons.

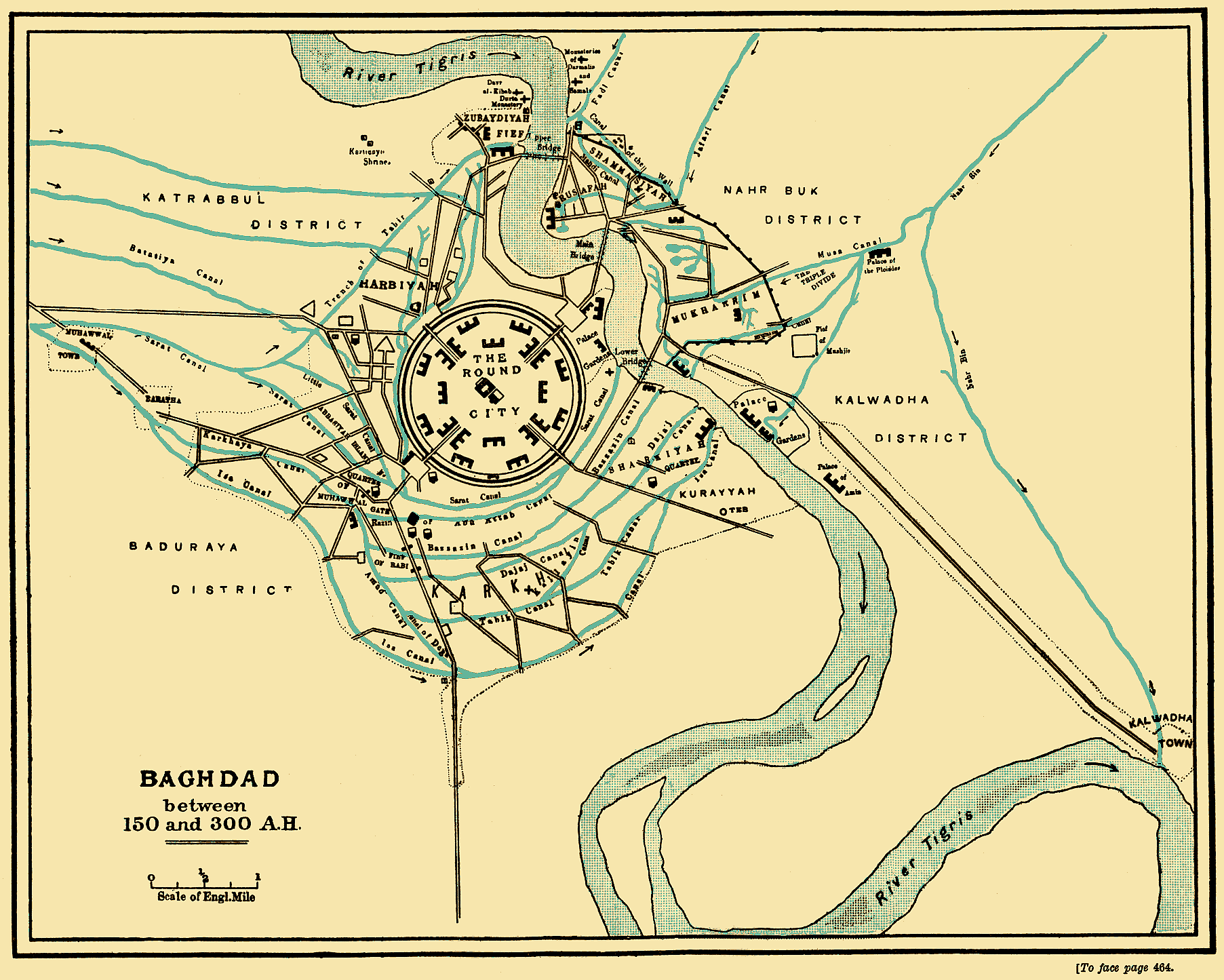

Ahmad ibn Fadlān was born in the capital of the Abbasid caliphate, the recently established cosmopolitan and multicultural city of Baghdad. We know little of his life apart from what he describes in his account of his travels, but he appears to have served as an expert in Islamic theology and law in the court of Caliph Miqtadir (908-932 CE).

A map of the city of Baghdad between 767-912 CE, by William Muir, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As such, Ahmad was appointed as secretary to a diplomatic mission (921-22 CE) sent by Miqtadir to the ruler of the Turkic-speaking Bulghārs living in the Volga river valley, Almish ibn Yitlawāt. Almish appears to have decided to convert to Islam in order to obtain military and financial assistance from the otherwise conveniently distant caliph against the Judaeo-Turkic Khazars, who controlled most of the trade in the Volga region from their capital at Itil. Ahmad ibn Fadlān’s account survives only because it was incorporated into later compilations of travel accounts.

The most famous part of Ibn Fadlān's account is his description of his encounter with a band of Rūs in the Volga region. A version of this account was translated into English early in the twentieth century. Ibn Fadlān's somewhat sensationalist description of the Vikings became the basis for Michael Crichtons’ Eaters of the Dead (1976), which was turned into a film, The 13th Warrior (1999). Both featured fictional versions of Ibn Fadlān.

Who were the Rūs?

The Rūs described by Ibn Fadlān have traditionally been associated with Viking traders, although the particular group described appears to have assimilated elements from the cultures with whom they traded. The Vikings appear to have originated in Scandinavia, but quickly raided and traded their way throughout Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Volga and Dnieper river systems. Vikings traded furs, amber, honey, swords, and slaves for luxury items and silver and gold, and were present in major trading cities such as Constantinople (modern day Istanbul) and Baghdad (modern day Iraq).

Map showing the major Varangian trade routes. The Viking trade routes to Constantinople are outlined in purple and those to are outlined in red. Other trade routes are shown in orange. Created by Brian Gotts, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Archaeologists uncovering Viking burials and hidden treasure hoards have found Islamic, Byzantine, and European coins as well as beautifully crafted weapons and jewelry and quantities of precious metal cut from crafted objects (hack-silver) or twisted into easy to carry rods, torques (necklaces), and bracelets.

The Vale of York hoard, a tenth-century Viking treasure hoard, uploaded by Seth Whales, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Seasoned sailors and warriors, the Rūs and other groups were also hired by Byzantine emperors as members of the imperial Varangian guard and as experts serving in the Byzantine army and navy. However, the portrayal of the Vikings as filthy, idol-worshipping, human-sacrificing savages still prevails in popular culture, partly due to negative representations of the Rūs by Islamic and Christian writers (see the excerpt below).

Viking expeditions (represented by the blue line), uploaded by Giusca Bogdan, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Further Resources:

Ahmad ibn Fadlān, "The Book of Ahmad ibn Fadlān, 921-922," in Ibn Fadlān and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North, trans. Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone (Penguin Classics, 2011).

Reading Questions:

For what kind of audience(s) might Ibn Fadlan have written his account of the Rūs? How does this impact Ibn Fadlan's depiction of the Rūs? Explain in detail.

Which elements of Rūs culture horrify Ibn Fadlan? Why do they horrify him? Make a list.

How might these elements of Rūs culture contrast with the urban culture of Baghdad and Ibn Fadlan's religious upbringing?

How might Ibn Fadlan attempt to convert a Rūs to Islam? What might the Rūs say to Ibn Faldan in return?

What possessions are prized most by Ibn Fadlan and the Rūs? What might this tell us about global trade in this period?

Would you rather live in Rūs society or Abbasid society? Why?

Ibn Fadlān's Account of the Rūs:

The translation below is adapted from that by Albert Stanburrough Cook, originally published as "Ibn Fadlān's Account of Scandinavian Merchants on the Volga in 922," The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 22.1 (1923), 54-63. A full version of the article may be found at http://www.jstor.com/stable/27702690.

1. I saw how the Rūs had arrived with their wares and had pitched their camp beside the Volga River. Never did I see people so gigantic; they are as tall as palm trees, and florid and ruddy of complexion. They wear neither coats nor caftans, but the men among them wear a garment of rough cloth, which is thrown over one side, so that one hand remains free. Every one carries an ax, a dagger, and a sword, and without these weapons they are never seen. Their swords are broad, with wavy lines, and of Frankish manufacture. From the tip of the fingernails to the neck, each man is tattooed with pictures of trees, living beings, and other things.

2. The women carry, fastened to their bosoms, a circular brooch made of iron, copper, silver or gold, according to the wealth and resources of their husbands. Fastened to the brooch there is a ring, and attached to that a dagger, all attached to their bosom. Around their necks they wear gold and silver chains. If the husband has 10,000 dirhems, he has one chain made for his wife; of 20,000, two; for every 10,000, one chain is added. For this reason it often happens that a Rūs woman wears a large number of chains around her neck.

3. Their most highly prized ornaments consist of green ceramic beads, of one of the varieties which are found in their ships. They make great efforts to obtain these, paying as much as a dirhem for a single bead, and string them into necklaces for their wives.

_(1).jpg?revision=1)

A selection of beads, including a large 'melon' style bead with ribbed edge, clear glass, slightly yellowed, from the Viking age Galloway Hoard. Photograph by the National Museums Scotland, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

4. They are the filthiest creatures that God ever created. They do not wipe themselves after defecating or urinating, nor do they bathe after sexual relations or after eating. They are like wild asses.

5. They come from their own land, anchor their ships in the Volga, which is a great river, and build large wooden houses on its banks. In each of these houses there live ten or twenty of them, more or less. Each man has a raised platform where he sits with the beautiful women he has for sale. As likely as not he enjoys one of them while a friend looks on. At times several of them are busy in this way at the same moment, each in full view of the others. Now and again a merchant will come to a house to purchase a woman, to find that her master is embracing her, and not giving her over until he has fully satisfied himself.

6. Every morning a woman comes and brings a tub of water and places it before her master. He proceeds to wash his face and hands in this and then his hair, combing it out over the tub. Then he blows his nose and spits into the tub, and leaving no dirt behind, conveys it all into this water. When he has finished, the girl carries the tub to the man next to him, who does the same. And so she continues carrying the tub from one to another, until each of those in the house has blown his nose and spit into the tub, and has washed his face and hair.

7. As soon as their ships have reached the anchorage, every one goes ashore, having at hand bread, meat, onions, milk, and strong drink. They go with these to a high upright piece of wood, carved with the image of a human face; this is surrounded by smaller statues, and behind these there are still other tall pieces of wood driven into the ground. He advances towards the large wooden figure, prostrates himself before it, and addresses it in this way: "Oh my lord, I have come from a far-off land, bringing with me such and such a number of girls and such and such a number of sable skins" and when he has listed out all his merchandise in this way, he continues, "I have brought you this present," laying before the wooden statue what he has brought. And then he says, "I ask you to grant me a purchaser who has gold and silver coins, who will buy from me to my heart's content, and who will refuse none of my demands." After saying this, he leaves. If his trade goes poorly, he then returns and brings a second or even a third present. If he still continues to have difficulty in obtaining what he desires, he brings a present to one of the small statues and begs for its intercession, saying "These are the wives and daughters of our lord." Continuing on in this way, he goes to each statue in turn, prays to it, begs for its intercession, and bows humbly before it. If it then happens that his trade goes very well and he gets rid of all his merchandise, he reports: "My lord has fulfilled my desire; now it is my duty to repay him." He then takes a number of cattle and sheep, slaughters them, and gives a portion of the meat to the poor. He then carries the rest before the large statue and the smaller ones surrounding it, hanging the heads of the sheep and cattle on the large piece of wood planted in the ground. When night falls, dogs come and devour it all. Then he who has placed [the offering] exclaims: "I have pleased my lord well; he has consumed my gift."

8. If one of them gets sick, they set up a tent at a distance, in which they place him, leaving bread and water at hand. After this they never approach or speak to him or visit him the entire time [he is ill], especially if he is a poor person or a slave. If he recovers and rises from his sick bed, he returns to his own. If he dies, they cremate him; but if he is a slave they leave him as he is, until in the end he is devoured by dogs and birds of prey.

9. If they catch a thief or robber, they lead him to a thick and tall tree, fasten a strong rope around his neck, string him up, and let him hang until he drops to pieces by the action of the wind and rain.

10. I was told that the least of what they do for their chiefs when they die is to consume them by fire. When I was finally informed of the death of one of their great men, I tried to witness what happened. First they laid him in his grave--over which a roof was built--for the period of ten days, until they had completed the cutting and sewing of his [funeral] clothes.

11. In the case of a poor man, however, they merely build for him a boat, in which they place him and consume it with fire. When a rich man dies, they gather his possessions and divide them into three parts. The first part is for his family; the second part is expended for the [funeral] garments they make; and with the third part they purchase strong drink for the day when the slave girl kills herself and is burned with her master. To the use of strong drink they abandon themselves in mad fashion, drinking it day and night; it is not uncommon for one of them to die with the drinking cup still in his hand.

12. When one of their great men dies, his family asks his slave girls and slave boys: "Which one of you will die with him?" Then one of them answers, "I." From the time that word is spoken, they are no longer free: even if they wish to change their minds, they are not allowed to. For the most part, however, it is the girls who offer themselves. And so, when the man I mentioned above had died, they asked his slave girls, "Who will die with him?" On of them answered, "I." She was then entrusted to two female slaves, who were to keep watch over her, accompany her wherever she went, and even, on occasion, wash her feet. The people now began to busy themselves with the dead man; they cut out the clothes for him and prepared whatever else was necessary. During this whole time, the [chosen] slave girl devoted herself to drinking and singing, and was cheerful and happy.

13. When the day had now come that the deceased man and the slave girl were to be committed to the flames, I went to the river where his ship was, but found that it had already been drawn ashore. Four corner-blocks of birch and other wood had been placed in position for it, while around it were stationed large wooden figures in the likeness of human beings. [1] Then the ship was brought up and placed on the timbers mentioned before. Meanwhile, the people began to walk back and forth, speaking words I did not understand. The deceased man, meanwhile, lay at a distance in his grave, as they had not yet removed him from it.

The preserved remains of the Oseberg Ship, now located in the Viking Ship Museum (Oslo). Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

14. Next they brought a couch, placed it in the ship, and covered it with Byzantine silk brocade, wadded and quilted, with pillows of the same material. An old woman, whom they call the "Angel of Death," came and spread the articles mentioned on the couch. It was she who attended to the sewing of the garments and to all the necessary items; it was she, also, who was to kill the slave girl. I saw her; she was dark, [2] thick-set, with a sinister expression.

15. When they cam to the grave, they removed the earth from the wooden roof, set the roof to one side, and drew out the deceased man, wrapped in the clothing in which he had died. Then I saw that he had turned quite black, due to the coldness of that region. Near him in the grave they had placed strong drink, fruit, and a lute; all these they now removed. The dead man's body had not changed except for his color. They now clothed him in trousers, socks, boots, tunic and kaftan made of brocade with gold buttons, placing on his head a brocade hat trimmed with sable fur. Then they carried him into a tent placed in the ship, seated him on the wadded and quilted coverlet, supported him with the cushions, and bringing strong drink, fruit, and basil, placed these all next to him. Then they brought in bread, meat and onions which they set out before him. [3]

16. Then they brought a dog, which they cut in half and threw into the ship. They placed all his weapons next to him and then led up two horses, which they chased until they were dripping with sweat, at which point they cut them into pieces with their swords and threw their flesh into the ship. Two oxen were then brought forward, cut into pieces, and flung into the ship. Finally they brought a rooster and a hen, killed them, and threw them [into the ship] as well.

17. The slave girl who had devoted herself to death meanwhile went back and forth, entering one after another of the tents which they had there. The occupant of each tent had sex with her, saying, "Tell your master, 'I did this only for love of you.'" [4]

18. When if was now Friday afternoon, they led the girl to an object they had constructed, which looked like the framework of a door. She then placed her feet on the extended hands of the men, was lifted up above the framework, and spoke something in her language, at which point they lowered her down. Then they lifted her up again and she did what she had done before. Once more they lowered her, then lifted her a third time, while she did what she had done the previous times. They then handed her a hen. She cut off its head and threw it away, but the body of the hen was flung onto the ship. I questioned the interpreter about what it was that she had done. He replied: "The first time she said, 'There I see my father and mother'; the second time 'There I see all my dead relatives sitting'; the third time, 'There is my master, who is sitting in Paradise. Paradise is so beautiful, so green. With him are his men and slave boys. He calls me; take me to him.'" Then they led her away to the ship. [5]

19. Here she took off her two bracelets and gave them to the old woman who was called the Angel of Death, who was to kill her. she also took off her two anklets and passed them to the two young girls who served her, who were the daughters of the woman known as the Angel of Death. Then they lifted her into the ship, but did not yet admit her to the tent. Now men came up with shields and staves and handed her a cup of strong drink. This she accepted, sang over it and then drank it. "With this," the interpreter told me, "she is taking leave of those who are dear to her." Then another cup was handed to her, which she also took, and began a lengthy song. The old woman urged her to drain the cup without lingering and to enter the tent where her master was.

20. By this time, as it seemed to me, the girl had become dazed; she acted as if she were trying to enter the tent but thrust her head forward between the tent and the ship. The old woman took her by the head and drew her into the tent. At this moment, the men began to beat on their shields with their staves, in order to drown out the noise of her cries, which might have terrified the other slave girls and deterred them from seeking death with their masters in the future. Then six men followed her into the tent and [had sex] with the girl, one after another. Then they laid her down by her master's side, while two of the men took her by the feet and two by the hands. The old woman known as the Angel of Death now knotted a rope around her neck and handed the ends to two of the men to pull tight. Then with a broad-bladed dagger she stabbed her between the ribs, and drew the blade out, while the two men strangled the girl with the rope until she was dead.

21. The next of kin to the deceased man now drew near, and taking a piece of wood, lit it and walked backwards toward the ship. He held the stick in one hand while the other shielded his buttocks, as he was naked. He held the stick until the wood which was piled under the ship took fire. Then the others came up with staves and firewood, each one carrying a stick already lit at the upper end, and all threw them on to the [funeral] pyre. The pile was soon aflame, then the ship, and finally the tent, the man, the girl, and everything else on the ship. A terrible storm began to blow up, and thus intensified the flames, and gave wings to the blaze.

22. At my side stood one of the Rūs, and I heard him talking with the interpreter, who stood near him. I asked the interpreter what the Rūs had said, and received this answer. "'You Arabs,' he said, 'must be a stupid set! You take him who is to you the most respected and beloved of men and cast him into the ground to be devoured by creeping things and maggots. We, on the other hand, burn him in an instant, so that he immediately, without a moment's delay, enters into Paradise.'" at this he burst into uncontrollable laughter, and then continued: 'It is the love of the Master that causes the wind to blow and snatch him away in an instant.'" And in very truth, before an hour had passed, ship, wood, and girl had, with the man, been turned into ashes.

23. They then heaped over the place where the ship had stood something a bit like a rounded hill, and put up at the center of it a large wooded post. They carved on it the name of the deceased along with that of the king of the Rūs. After doing this, they left that place.

24. It is the custom among the Rūs that with the king in his hall there should be four hundred of the most warlike and trusty of his companions,who stand ready to die with him or offer their life for his. Each of them has a slave girl to wait on him--to wash his head and to prepare food and drink; and in addition, he has another slave girl who serves as his concubine. These four hundred sit below the king's high seat, which is large and decorated with precious stones. Accompanying him on his high seat are forty girls, destined for his bed, whom he causes to sit near him. Now and again he will proceed to have sex with one of them in the presence of the men of his following described above. The king does not get down from his high seat, and is therefore obliged, when he needs to relieve himself, to make use of a vessel. If he wishes to ride, his horse is led up to the high seat, and he mounts it from there. When he is ready to alight, he rides his horse up so close that he can step immediately from it to his throne. He has a lieutenant who leads his armies, fights his enemies, and acts as the king's representative in dealings with his subjects.

Notes for the translation:

[1] The description of statues is missing from the Lunde and Stone translation. They instead perhaps more accurately interpret this passage as referring to the construction of a ship's cradle for the beached ship (50).

[2] Lunde and Stone substitute "a witch" for "dark" (50). What issues might be raised by either of these choices of words to describe the old woman?

[3] The description of the bread, meat, and onions is supplied from Lunde and Stone's translation (51).

[4] Lunde and Stone translate this as "Tell your master that I only did this for your love of him" (52).

[5] As Lunde and Stone show (52), this passage is heavily reconstructed, which poses problems of interpretation of what the slave girl was actually saying.