1.3: Socio-Cultural Context

- Page ID

- 156837

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \) \( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)\(\newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\) \( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\) \( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \(\newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\) \( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\) \( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)\(\newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

Historical Context

- We can learn about the historical context to help us interpret the content and understand the meaning of two seventeenth-century Dutch paintings.

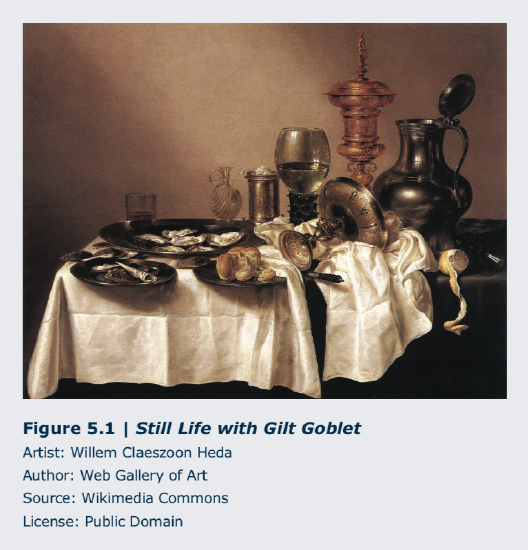

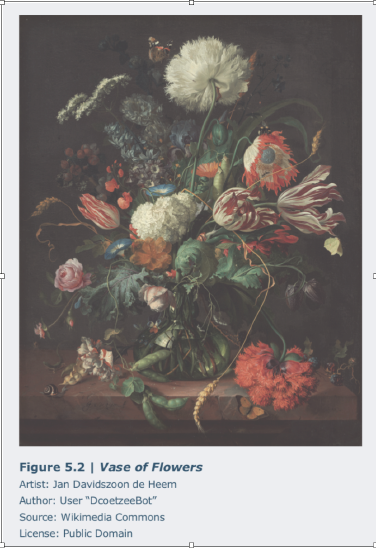

- Willem Claesz. Heda (1594-1680, Netherlands) created Still Life with a Gilt Cup in 1635, and Jan Davidsz. de Heem painted Still Life with Flowers around 1660. (Figures 5.1 and 5.2)

- Although depicting different types of things, each of these paintings is still life, an arrangement of objects both made by humans and found in nature, such as flowers, fruit, insects, sea creatures, and animals from the hunt. A still life falls into a subject category known as genre subjects or scenes of everyday life.

- Both Heda and de Heem specialized in painting still lifes that were beautifully arranged and stunningly lifelike. Each was well known for his ability to depict a variety of textures and surfaces often displayed side-by-side, as we can see here, to create a dazzling and sumptuous visual array.

- The subject of Heda’s painting, Still Life with a Gilt Cup, is ostensibly the remains of a meal of oysters and bread, but it is even more about all the objects accompanying the food. (Figure 5.1) The tin plates and open-lidded pewter pitcher are relatively simply fashioned and could have been made by local craftsmen. But the remaining items, including a spiral ribbed clear glass cruet for oil or vinegar behind the tin bowl of oysters, the green glass wine römer, or goblet, decorated with prunts (applied blobs of molten glass, here drawn into points), and the tall, heavily ornamented, and gilded vessel topped by a lid with a figure of a warrior, are all luxury goods. They indicate wealth and good taste, and they allude to Holland’s importance as a nation of traders who import beautiful objects from around the world.

- In a similar fashion, in Still Life with Flowers de Heem sets before us, teeming with life and in abundant disarray, the beauty and bounty of nature. (Figure 5.2) But he also shows the swift passing of the seasons by depicting flowers, fruits, and vegetables that bloom and ripen throughout the year. The tulips from highly prized and costly bulbs imported by the Dutch from the Ottoman Empire (modern Turkey) honeysuckle, roses, carnations, peas, grapes, and corn introduced to Europe from the Americas are among the profusion of colors and forms that de Heem unrealistically depicts as all in season at the same time. The viewer would instead know that long before the orange carnation blossomed in the fall, the blood-red striped tulip would have withered in the spring. De Heem is reminding us in this vanitas (Latin: vanity) still life of our own mortality and the transience of life in the face of certain death.

- Both paintings’ messages reflect the importance in the Protestant faith, as practiced in Holland at the time, of the believer’s direct connection to God without the need for intercessors.

Social Context

- Lilly Martin Spencer (1822-1902, USA) painted Conversation Piece around 1851-1852. (Figure 5.3)

- A genre painting, it depicts an everyday scene of a mother holding her infant in her lap while the father stands beside them playfully dangling some cherries above the baby’s eager grasp.

- It is a quiet scene of family life, a moment of contentment and peace, with the dining table not yet cleared after a meal adding an even greater sense of intimacy and informality. Spencer was the only prominent female painter at that time in the United States, and the majority of her works are narrative genre pieces such as this one. They are scenes of domestic life, often suggesting a story told through the setting, the arrangement and gesture of the figures, and their facial expressions.

- In Spencer’s painting, the woman represents the feminine ideal of a nurturing and content mother. But rather than showing a father who holds himself apart from the womanly, domestic sphere—as was far more common at the time Spencer depicts the man in an equally caring and warm role. An oval is formed by the mother’s bent head and arm which extends from her hand supporting the baby’s head through the baby’s upraised arm to the father’s bent arm, his bowed head, and his left arm resting on the back of the mother’s chair. At odds with many at the time who believed men and women existed in separate spheres, Spencer draws the family into one circle.

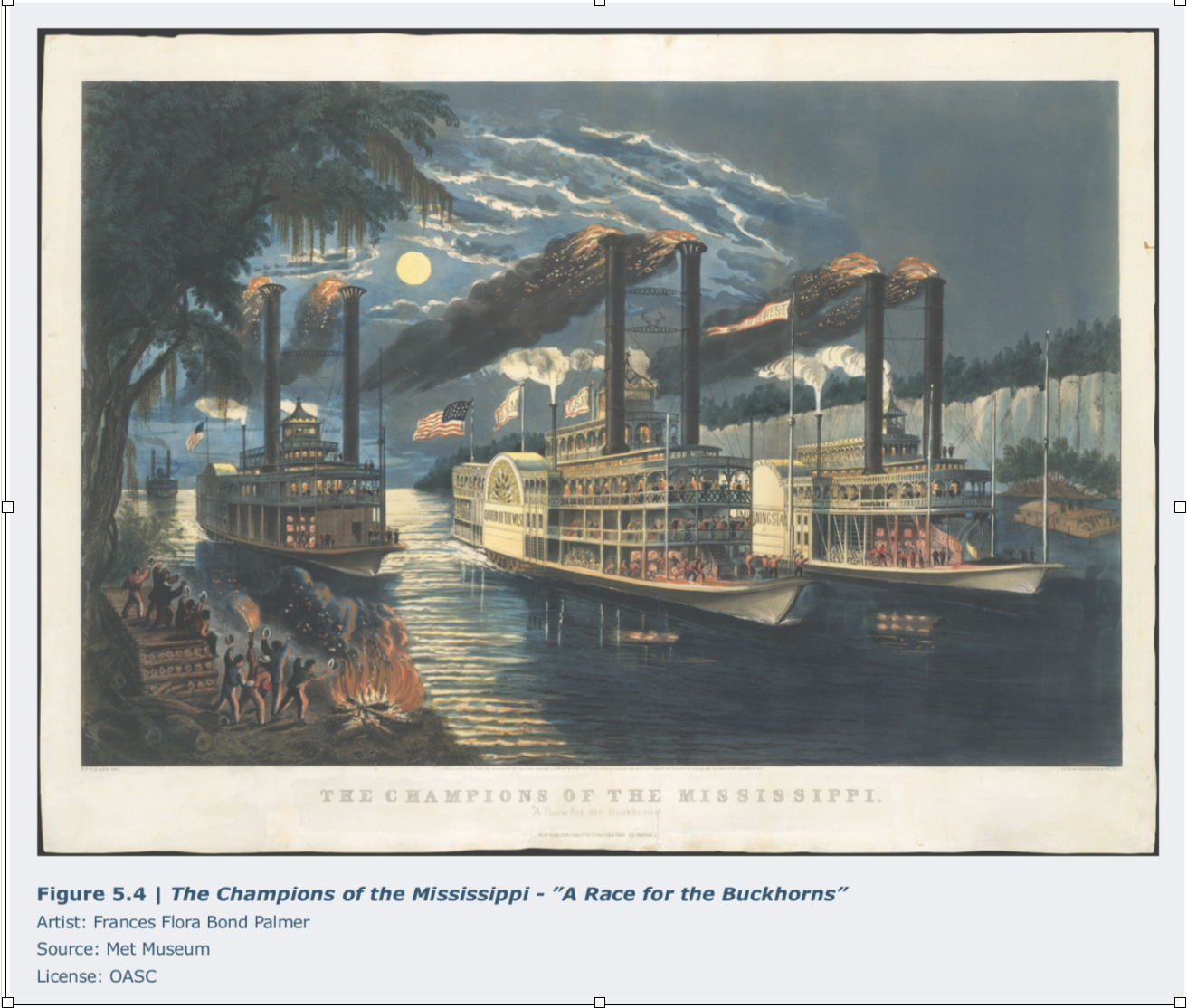

- American industrialism worked hand-in-hand with American ingenuity. Steamboat routes on the Mississippi River and its tributaries substantially contributed to the growth of settlements and cities from New Orleans to Pittsburgh began in 1811.

- The artist who drew the Champions of the Mississippi was Frances Flora Bond Palmer (1812-1876, USA). Palmer, like Lilly Martin Spencer, supported her family as a full-time artist.

- As was the case with the majority of scenes Palmer created, she did not witness the race between the steamboats Queen of the West and Morning Star or the cheering crowd on the shore. She depicted numerous such scenes, however, as competitions such as this were commonplace and prints commemorating them were popular and sold well. The races and the steamboats were a source of pride and a celebration of American ingenuity, competitiveness, and success.

- For those who owned a print such as The Champions of the Mississippi, the vast majority of whom had never seen the river or a steamboat competition, it represented the open possibilities of America’s greatest waterway and indomitable spirit.

Personal or Creative Narrative Context

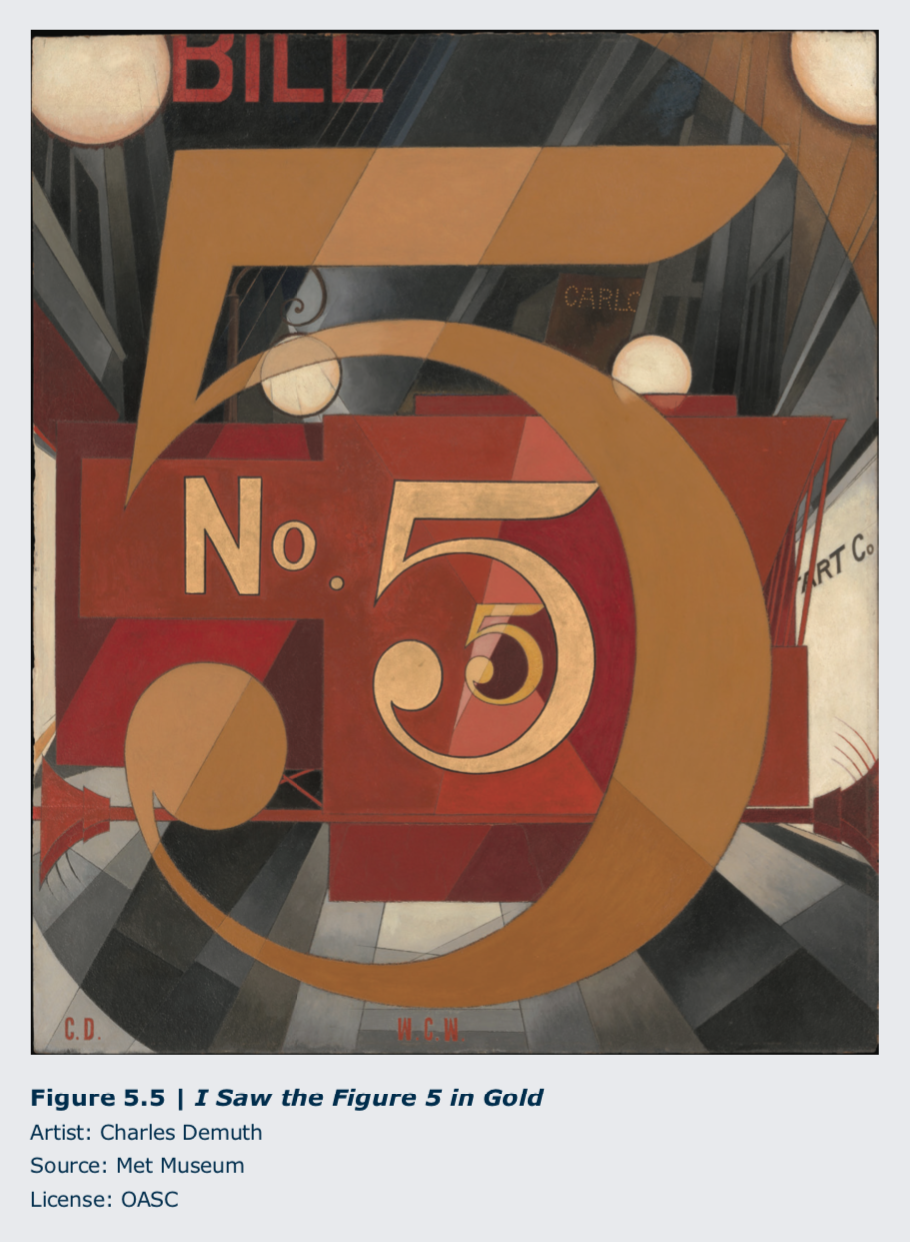

- Charles Demuth (1883-1935, USA) painted The Figure 5 in Gold in 1928. (Figure 5.5) Demuth met poet and physician William Carlos Williams at the boarding house where they both lived in Philadelphia while studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Demuth’s painting is one in a series of portraits of friends, paying homage to Williams and his 1916 poem “The Great Figure”:

Among the rain and lights I saw the figure 5 in gold on a red firetruck moving tense unheeded to gong clangs siren howls and wheels rumbling through the dark city.

- Williams described the inspiration for his poem as an encounter with a fire truck as it noisily sped along the streets of New York, abruptly shaking him from his inner thoughts to a jarring awareness of what was going on around him.

- Demuth chose to paint his portrait of Williams not as a likeness but with references to his friend, the poet.

- The dark, shadowed diagonal lines radiating from the center of his painting, punctuated by bright white circles, capture the jolt of the charging truck accompanied by the clamor of its bells. The accelerating beat of the figure 5 echoes the pounding of Williams’s heart as he was startled. It was the sight of the number in gold that Williams was first aware of at the scene, and Demuth uses the pulsing 5 to symbolically portray his friend, surrounded by the rush of red as bright as blood with his name, Bill, above as if flashing in red neon.

Political Context

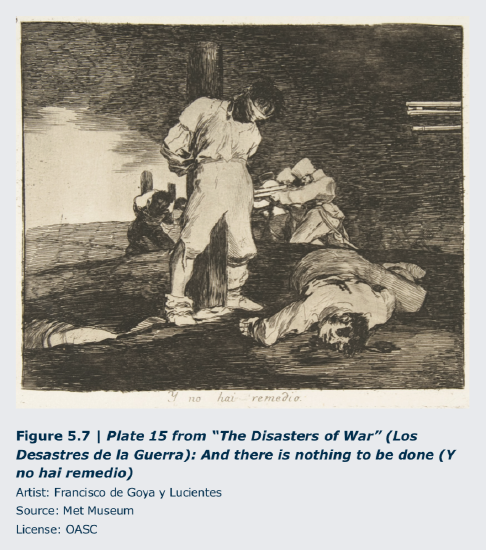

- Francisco de Goya y Lucien- tes (1746-1828, Spain) was court painter to King Charles IV from the beginning of his reign in 1789 until Napoleon ousted Charles from his throne in 1808 during the French invasion of Spain.

- Goya was hired the same year to make a visual re- cord of the bravery of the Spanish people against the onslaught of the French invaders. The impact of what Goya saw, however, changed the direction and tone of the series of prints he made from the unflinching courage of his fellow citizens to despair over the barbarous atrocities committed and merciless suffering endured by all who are trampled in the path of war.

- He created the series of eighty-two etchings, The Disasters of War, between 1810 and 1823. Y no hai Remedio (And There’s Nothing to Be Done) is the nineteenth print in the series; it reflects the hopelessness of war. (Figure 5.7) There is no escape, nor is there justice. Both civilians and soldiers become de-humanized and numb in the endless slaughter, here in the form of a firing squad.

Scientific Context

- Art and science are inextricably linked. The words “technique” and “technology” both originate from the ancient Greek word tekhne, which means art. For the Greeks, both art and science were the study, analysis, and classification of objects and ideas.

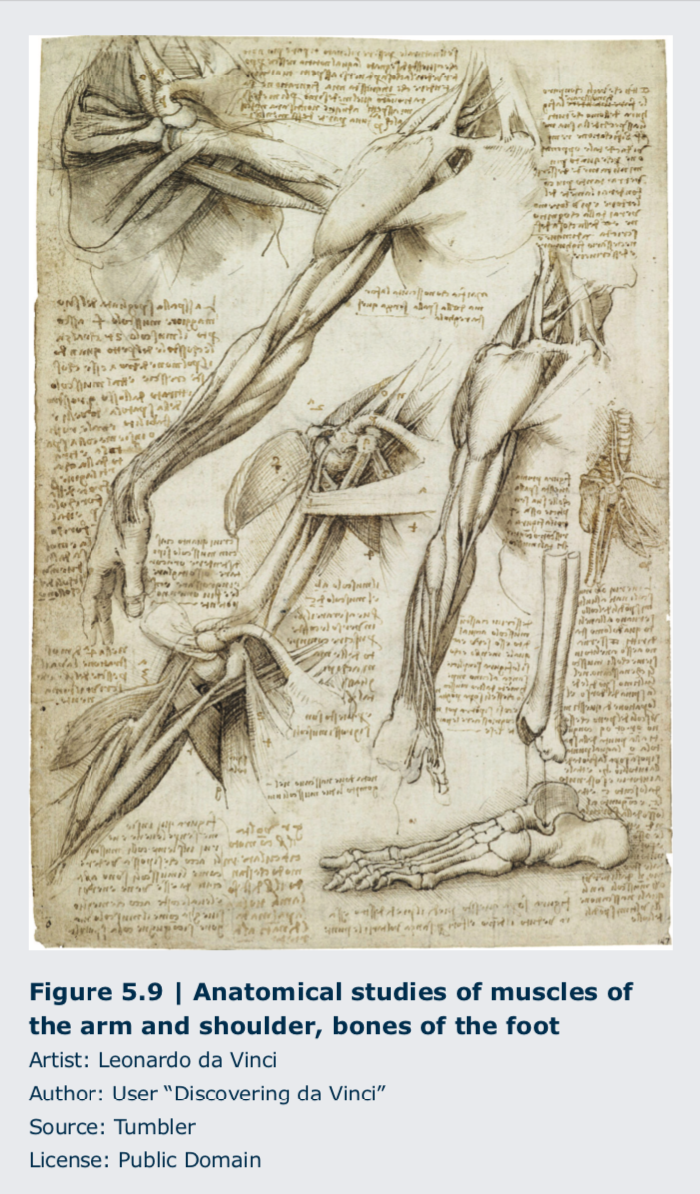

- Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by how things work. The mechanics of nature, machinery, and the human body were all worlds to be explored deeply in order to be understood at their most essential, truthful levels.

- Although he was interested in human anatomy throughout his career, he spent the last twelve years of his life systematically studying and documenting his findings. He began in the winter of 1507-08 with a series of pen-and-ink drawings that he made of a dissection he carried out on an old man. In the winter of 1510-11, he completed additional dissections, probably working with anatomy professor Marcantonio della Torre at the University of Pavia. (Figure 5.9)

- “Steamboats.” American Eras. 1997. Encyclopedia.com. (June 22, 2015). http://www.encyclopedia.com/ doc/1G2-2536600971.html

- Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi (Boston: James R. Osgood & Co.), 1883. Accessed from: http://www.gutenberg.org/ files/245/245-h/245-h.htm

- Georgia O’Keeffe, “About myself ” in Georgia O’Keeffe: Exhibition of oils and pastels (New York: An American Place: 1939).