13.5: Ritual, spirituality, and transcendence

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147856

Ritual, spirituality, and transcendence

Spirituality remains important, but it takes on new forms in the global contemporary era.

1980 - present

Roger Minick, Woman with Scarf at Inspiration Point, Yosemite National Park

by ELIZABETH GERBER, LACMA and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Roger Minick, Woman with Scarf at Inspiration Point, Yosemite National Park (Sightseer series), 1980, dye coupler print, 38.1 x 43.18 cm, ©Roger Minick (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), a Seeing America video

Mariko Mori, Pure Land

Floating on a lotus blossom

Set within a golden landscape, a female figure serenely floats above a lotus blossom while six alien musicians whirl by on bubbly clouds. Her pink robes mirror the predominantly pale orange, yellow and pink of the water, land and sky—firmly embedding her within the tranquil scene. Pure Land, a photograph set within glass, is the counterpart of Mori’s three-dimensional video installation, Nirvana, 1997. Nirvana animates the imagery we see in Pure Land. Viewed within a darkened room with the aid of three-dimensional glasses, Nirvana’s audience was limited to a group of 20 people at a time. During the seven minute video, the central female figure would hum and whisper echoed rhythms as if meditating, while the little musicians floated around her. At the conclusion, a fan came on and blew cool, scented air into the audience’s faces. Through the integration of sensory elements such as three-dimensional imagery, sound, scent, and the gentle touch of a breeze, combined with the limited viewing audience, Nirvana created an immersive, intimate experience. As its photographic counterpart, Pure Land captures a moment of this experience, enabling the viewer a longer, perhaps more meditative, relationship with the work.

Symbolism and spiritual allusions

Every element we see here has significance that may not be apparent at first glance—the serene landscape, with its golden sky, smooth pink land masses, and perfectly still water, is rich with symbolism. Pure Land is set during sunrise in the landscape of the Dead Sea, the lowest point on earth, called “dead” because the high salinity of its water does not support fish or plant life. In Shinto tradition, salt is used as an agent of purification. Floating in the water is a lotus blossom—symbol of purity and rebirth into paradise. This blossom resembles one in Mori’s 1998 sculptural installation, Enlightenment Capsule (left), which featured a rainbow-colored acrylic lotus blossom set within a space-age capsule illuminated by sunlight. In both Enlightenment Capsule and Pure Land Mori blends traditional symbolism with futuristic elements. On the right hand side of the background of Pure Landis a fantastical object which resembles a playful futuristic spacecraft with arms. This may be a variation of a Tibetan stupa—a sacred Buddhist monument originally used as a burial mound. Through her imaginative reinterpretation of symbols steeped in tradition, the artist creates a timeless setting appropriate for meditation on death, purification, and rebirth.

Immersion

The distant horizon line, combined with the larger island in the foreground that seems to continue into the viewer’s space, create a sense of immersion, as if one were present with these fantastical figures. Perhaps this feeling of personal involvement ties in with the title itself, Pure Land, which is the paradise of Amida (or Amitabha) Buddha who descends to greet devotees at the moment of their death and takes them back to his “Pure Land of Perfect Bliss.”

Beginning with the eleventh century in Japan, several paintings and sculptures were made on this theme, such as the Descent of Amida and the Heavenly Multitude (above). In this type of imagery, Amida Buddha, resting on a lotus blossom and holding his hands in a symbolic gesture known as a mudra, is typically surrounded by celestial attendants in a sea of swirling clouds. These attendants are boddhisattvas, enlightened beings who act out of great compassion to help others achieve enlightenment. In a sculptural example from Byodo-in Temple, 52 boddhisattvas fly on clouds on either side of Amida Buddha (below); some are seated quietly with their hands joined in prayer, some hold a lotus blossom to receive the soul of the deceased, while others are playing musical instruments.

Oneness and universality

In Mori’s version, these celestial attendants are pastel-colored alien figures with large pointy heads and delicate bodies. Each figure plays a different instrument as they float on their light blue bubbly clouds. The two musicians in the foreground are blurred, as if they are flying quickly toward the viewer. These muscians appear again in a later sculptural installation by Mori, Oneness , 2003 (left). In this work, the six aliens are given three-dimensional form, complete with soft, flesh-like material. They stand in a circle facing outward as they hold each other’s hands. The viewer becomes an active participant in the work — when a person hugs one of the figures, its eyes light up and you feel its heartbeat. As in the Nirvana video installation upon which Pure Land is based, Mori seems to want to engage more than just the viewer’s sense of sight and for each participant to have a direct experience with the artwork. Perhaps more significantly, Oneness is a metaphor for bringing in the outsider, achieved through revealing commonalities of experience. The binding together of seemingly disparate realities is a central theme throughout Mori’s work.

Artist as object

Another element typical in Mori’s work is for the artist to cast herself in the principle role, and Pure Land is no exception. The central female figure is the artist herself, wearing an elaborate costume and headdress, both of her own design. Born in Tokyo in 1967, Mori studied design at Tokyo’s Bunka Fashion College and worked part-time as a fashion model, which she originally considered a form of personal creativity. However, she found modeling an inadequate medium in which to express herself fully, so she began to stage elaborate tableaux, taking full creative control of the process, acting as director, producer, set and costume designer, and model. This recalls the practices of other photographers, most notably Cindy Sherman , as well as Yasumasa Morimura, the Japanese photographer notorious for substituting himself for figures in famous paintings throughout art history.

In the Pure Land photograph, Mori’s light blue, pupil-less eyes, gauze serenely somewhere beyond our vision. Like the Amida Buddha, she rests above a lotus blossom and holds her right hand in a mudra of blessing and teaching; the circle formed by the index finger and thumb is the sign of the Wheel of Law. In her left hand she holds a hojyu, or magical wishing jewel, in the shape of a lotus bud. This figure is inspired by Kichijoten, originally the Indian goddess, Shri Lakshmi, who was eventually incorporated into Buddhism, and typically represents fertility, fortune, and beauty. Here Mori bars comparison with a well-known eighth-century painting of Kichijoten from Yukushi-ji Temple in Nara. Similarities include the serene elegance, softly fluttering gown, and wish-granting jewel. The eighth-century painting depicts the clothing and appearance of an elegant lady of the Chinese Tang Dynasty, and it may have been an object of veneration during the annual New Year event when devotees prayed for happiness and fertility. In this manner, a beautiful, elegant woman was seen to embody the ideas of good fortune and prosperity and became an object of worship.

By taking on this ancient persona, Mori dissolves her own identity and is transformed into the elegant Tang lady and goddess of fortune, while simultaneously performing the welcoming role of Amida Buddha. Mori’s enlightened self-representation descends to guide the viewer into a “Pure Land of Perfect Bliss” of her own creation. Perhaps more significantly, the artist seeks to lead the viewer into her immersive paradise. In both formats, the multi-sensory video Nirvana and purely visual Pure Land photograph, the message is clear: enlightenment is for all.

Additional resources:

Mariko Mori at the Tokyo Museum of Contemporary Art

Video — The Artist Project: Mariko Mori (from The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Visualizing an Endless Universe: Mariko Mori Makes the Cosmos Life-Size

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Earth’s Creation

At nearly twenty feet wide and nine feet high, Emily Kwame Kngwarreye’s painting Earth’s Creation is monumental in its scale and impact, rivaling Abstract Expressionist masterpieces by Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock not only in size but also in its painterly virtuosity (see a photo of it in a gallery here, to get a sense of its scale). Patches of bold yellows, greens, reds and blues seem to bloom like lush vegetation over the large canvas. Comprised of gestural, viscous marks, each swath of color traces the movement of the artist’s hands and body over the canvas, which would have been laid horizontally as she painted, seated on (or beside) and intimately connected to her art.

The work made records at auction when it was sold in 2007 for over $1,000,000—the highest price ever fetched for a work by a female artist in Australia. Yet, just decades earlier, Kngwarreye was virtually unknown to the world outside her small desert community in the Australian country of Alhakere. A self-taught artist who was trained in ceremonial painting, she rose to international prominence only in her eighties, and enjoyed a flourishing career at the end of her life.

Rooted in tradition

Kngwarreye was born around 1910, and spent most of her life in an isolated Anmatyerr community in Central Australia. The area, however, was forcibly occupied by European pastoralist settlers in the 1920s, and the artist, alongside other members of her community, worked on the pastoral property (pastoral refers to the tending of cattle and sheep). In 1976, Aboriginal land rights were legally granted, and she was able, finally, to live independently.

Aboriginal culture has long been intimately connected to the landscape of Australia; inhabited by humans for over 40,000 years, the region is characterized by deserts, grasslands and dramatic arched rock formations. Kngwarreye was an established elder of her community and was trained to create ceremonial sand paintings inspired by her ritual “dreamings,’” as well as to paint decorative motifs on women’s bodies as part of a ceremony called Awelye. These visual forms were connected to cultural expressions in song, storytelling and dance. While her paintings have never been figural, they remain influenced by the culture in which she grew up as well as the natural environment.

Artistic intervention

In the late 1970s, Kngwayere began to work in the medium of batiks, making works that were purely artistic endeavors for the first time. In 1977, she was a founding participant of the Utopia Women’s Batik Group. Her compositions were abstract and featured the motif of repeated dots, acting sometimes as a linear stroke, or elsewhere used to fill large patches of space. A decade later, in 1988, the S.H. Ervin Gallery in Sydney initiated a “Summer Project” that sought to facilitate the creation of Aboriginal art, as well as to establish a market for the genre. Sponsored by the collector Robert Holmes à Court, curators traveled to the Aboriginal homeland of Utopia and delivered acrylic paints and materials. After two weeks they returned to find “abstract and richly expressive” compositions created by many of the artists, and held a group exhibition in Sydney.

Kngwarreye’s painting Emu Woman (above) was selected for the cover of the exhibition catalogue as a gesture of respect for her seniority, as she was the oldest artist from the community. Dominated by rich, earthy tones, the painting—her first ever on canvas–contained references to plants and seeds that featured in her “dreaming” ritual. Against a dark field of charcoal, violet and black, the piece is punctuated with bright marks in tangerine and white hues, which lend the work an electric sense of energy and rhythm. Her decades-long experience in painting directly on the human body informs the curving swells of dotted marks that comprise the composition.

Critics lauded the piece, and virtually overnight, the artist received international exposure and unprecedented acclaim. The following year, Kngwarreye held her first solo exhibition at Utopia Art Sydney, after which she would be invited to participate in several renowned international exhibitions and biennales.

The “global” turn

The arc of Kngwarreye’s career runs alongside a period of tremendous change in Australia, moving from the end of a phase of colonial settlement through to a more ethical embrace of Aboriginal culture by the nation’s Western population. Yet the period in which she came to prominence also reflects changes taking place in the contemporary art world internationally, as the 1980s and 1990s saw a notable expansion within the mainstream to include non-Western or minority artists.

“Green time”

Earth’s Creation belongs to the “high colorist” phase in Kngwarreye’s work, which is characterized by a loosening of her compositions—which were no longer reliant on pseudo-geometric patterns—and the expansion of her color palette to include a range of tones beyond the familiar clay and ochre hues that dominated her prior works. Still connected to the natural environment, however, these works reference the changing atmospheric character of seasonal cycles. Earth’s Creation documents the lushness of the “green time” that follows periods of heavy rain, and makes use of tropical blues, yellows and greens. The piece has often been likened to Claude Monet’s studies of seasonal and temporal change, and given its formidable, room-filling scale, a comparison to the artist’s Water Lilies of 1914-26 (MoMA) might be remarkably apt.

Earth’s Creation was created as part of the larger Alhalkere Suite which contains twenty-two panels, and is still considered one of the most virtuosic of Kngwarreye’s immense and prolific artistic output. In the last two weeks of her life, Kngwarreye completed a suite of twenty-four small paintings. These were characterized by extremely broad, milky strokes of jewel-toned hues of blue and rose, and communicate the artist’s long-standing fascination with color and her sophisticated grasp of abstract composition.

Additional resources:

“Utopia: The Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye” at the National Museum Australia

Earth’s Creation at the Venice Biennale, Universes-in-Universe

The artist at the National Gallery of Australia

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, The Alhalkere suite from the National Gallery of Australia

Utopia: The Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, review by Chrischona Schmidt

Teacher notes for Emily Kame Kngwarreye: Alhalkere — Paintings from Utopia

Australia 1900-present on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

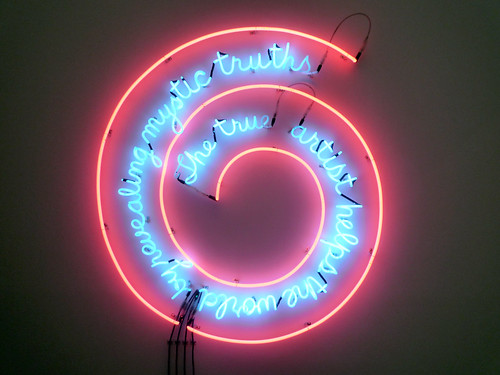

Bruce Nauman, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths

by JP MCMAHON

Bruce Nauman’s neon sign asks a multitude of questions with regard to the ways in which the 20th century conceived both avant-garde art and the role of the artist in society. If earlier European modernists, such as Mondrian, Malevich, and Kandinsky, sought to use art to reveal deep-seated truths about the human condition and the role of the artist in general, then Bruce Nauman’s The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths questions such transhistorical and universal statements. With regard to this work, Nauman said:

The most difficult thing about the whole piece for me was the statement. It was a kind of test—like when you say something out loud to see if you believe it. Once written down, I could see that the statement […] was on the one hand a totally silly idea and yet, on the other hand, I believed it. It’s true and not true at the same time. It depends on how you interpret it and how seriously you take yourself. For me it’s still a very strong thought.

The medium and the message

By using the mediums of mass culture (neon signs) and of display (he originally hung the sign in his storefront studio), Nauman sought to bring questions normally considered only by the high culture elite, such as the role and function of art and the artist in society, to a wider audience. While early European modernists, such as Picasso, had borrowed widely from popular culture, they rarely displayed their work in the sites of popular culture. For Nauman, both the medium and the message were equally important; thus, by using a form of communication readily understood by all (neon signs had been widespread in modern industrial society) and by placing this message in the public view, Nauman let everyone ask and answer the question.

While it is perhaps the words that stand out most, the symbolism of the spiral (think of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, 1969), also deserves attention having been used for centuries in European and other civilizations, such as megalithic and Chinese art, both as a symbol of time and of nature itself.

Transcendence?

Theosophy is interesting in this regard and was an important aspect of the early European Avant-garde. In particular, Theosophists believed that all religions are attempts to help humanity to evolve to greater perfection, and that each religion therefore holds a portion of the truth. Through their materials, artists had sought to transform the physical into the spiritual. In this sense, Malevich, Mondrian, and Kandinsky sought to use the material of their art to transcend it: Nauman, and other of his generation, did not.

Process over product

Instead, Nauman’s work transgresses many genres of art making in that his work explores the implications of minimalism, conceptual, performance, and process art. In this sense we could call Nauman’s art “Postminimalism,” a term coined by the art critic Robert Pincus-Witten, in his article “Eva Hesse: Post-Minimalism into Sublime” (Artforum 10, number 3, November 1971). Artists such as Nauman, Acconci, and Hesse, favored process instead of product, or rather the investigation over the end result. However, this is not to say they did not produce objects, such as the neon-sign by Nauman, only that within the presentation of the object, they also retained an examination of the processes that made that specific object.

In this sense, Nauman’s neon sign isn’t only an object, it’s a process, something that continues to make us think about art, artist, and the role that language plays in our conception of both. The words continue to ask this of each beholder who encounters them. Does the artist, the “true artist” really “reveal mystical truths”? Or confined to the specific culture that it was made in? If we are to believe the statement (remember, it is not necessarily Nauman’s, he merely borrows it from our shared culture), then we might, for example, recognize Leonardo da Vinci as a Neo-Platonic artist who showed us ultimate and essential truths through painting. On the other hand, if we reject the statement, then we would probably recognize the artist as just another producer of a specific set of objects, that we call “art.”

This type of logic and analytical thinking was influenced by Nauman’s reading of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations (1953). From Wittgenstein, Nauman took the idea that you put forth a proposition/idea in the form of language and then examine its findings, irrespective of its proof or conclusion. Nauman’s “language games,” his neon-words, his proposition about the nature of art and the artist continue to resonant in today’s art world, in particular with regard to the value we place on the artist’s actions and findings.

Additional resources:

This work of art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Art:21 page about Nauman’s The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truth

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

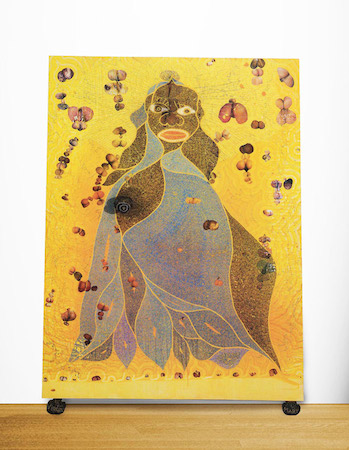

Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin Mary

Sensation

When the personal collection of British advertising executive and art collector Charles Saatchi went on tour in an exhibition called Sensation in 1997, viewers should have known to brace themselves for controversy. The show presented a cross-section of shocking work by a brash new generation of “Young British Artists,” including, for example, Marcus Harvey’s portrait of convicted child-murderer Myra Handley, and pornographic sculptural tableaux by Jake and Dinos Chapman. In London, the museum was picketed from day one, but the media attention eventually ushered in record turnouts.

In October of 1999, Sensation opened at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, where it was Chris Ofili’s iconic painting, The Holy Virgin Mary that incited the most heated debate. Mayor Rudy Giuliani threatened to close the city-funded institution on the grounds that this artwork was offensive to religious viewers. Two months later, the painting, which rests upon two large balls of elephant dung, was desecrated by an elderly visitor who smeared white paint over its surface, claiming that the image was “blasphemous.”

At first glance it seems easy to discern why the painting raised a few eyebrows: the inclusion of real shit and collaged pornography might be enough to offend conservative viewers. However, Ofili’s work is more nuanced than it appeared to his detractors; the piece reflects on art historical precedents while addressing identity politics, religion and pop culture. To grasp its complexity, one must look beneath the surface—as dazzling and shocking as it may be.

Iconic or iconoclastic?

Set against a shimmering gold background comprised of carefully placed dots of paint and glitter, the central figure in Ofili’s painting stares directly at her beholder, with wide eyes and parted lips. Her blue gown flows from the top of her head down to the amorphous base of her body, falling open to reveal a lacquered ball of elephant dung where her breast would be. Collaged images of women’s buttocks surround the Virgin; cut from pornographic magazines, they become abstract, almost decorative forms that refuse to signify until confronted up-close. The two balls of dung beneath the canvas are adorned with glittering letters spelling out the work’s title.

Formally, the use of gold and the front-facing Virgin link the work to Medieval icons, making the vulgarity of the pornographic images all the more stark. Yet, the artist claims that the sacred and the profane are not always opposed, even in traditional religious art:

As an altar boy, I was confused by the idea of a holy Virgin Mary giving birth to a young boy. Now when I go to the National Gallery and see paintings of the Virgin Mary, I see how sexually charged they are. Mine is simply a hip hop version.

Race, religion, and representation

It is perhaps Ofili’s final statement above that indicates the source of his critics’ anxieties. As Carol Becker has explained, Ofili is “transforming the Holy Virgin into an exuberant, folkloric image. (…) probably most controversial of all, he made his own representation of the Virgin, defiant of tradition.”[2] The “parody-like African mouth” and exaggerated facial features call attention to racial stereotypes, as well as to the assumed whiteness of biblical figures in Western representations. Ofili’s icon asks us to confront the possibility of a black Virgin Mary. Other works express Ofili’s interest in black culture more explicitly: paintings like the Afrodizzia series and No Woman No Cry make references not only to hip-hop and reggae but also to contemporary racial politics.

The triumph of painting

While his works pay homage to iconic black celebrities such as James Brown, Miles Davis, and Muhammad Ali, they are also just as much about the act of painting. With their psychedelic patterning, bright colors and textured surfaces, the images express Ofili’s desire to “get as deeply lost as possible in both the process of painting and the painting itself.”[3]

From his beginnings, the artist was passionate about the medium, even as painting grew out of favor in the wake of postmodernism. He enrolled at the Chelsea School of Art where he developed an expressionistic style, but his work really started to mature after an oft-mythologized trip to Africa.

Ofili was born in Manchester, England to Nigerian parents. When he was awarded a British Council grant in 1992, however, he ventured not to their home country but to Zimbabwe, in southern Africa. There, he was inspired by the abstract motifs found in San rock painting; these graphic marks found their way into the swirling backgrounds of his later compositions.

In Zimbabwe he also discovered elephant dung, and experimented with using it as an aesthetic medium, sticking it onto the surfaces of his canvases. As he later recalled, “it was a crass way of bringing the landscape into the painting,” as well as a nod to modernist art history through the dung’s status as a found object.[4]

The following year, back in Europe, Ofili was already at work with his new material. He staged a performance in Berlin and London entitled Shit Sale, a nod to the American artist David Hammons’ Bliz-aard Ball Sale of 1983, and later produced a work on canvas simply titled Painting with Shit on It, from which his mature style eventually emerged.

Combining visual pleasure with a conceptual practice

Ofili’s work is as formally-motivated as it is political. The artist did not only return to painting, he returned to decoration and visual pleasure, at a time when art was expected to comply with the more cerebral aesthetics of postmodernism. Perhaps his attraction to gaudy bright colors, earthy materials and glittering surfaces, paired with the highly conceptual stakes of his project, reflects another blending of sacred and profane, regarding the conservatism of the art world. By incorporating high and low art forms, historical narratives, religion and pop culture, The Holy Virgin Mary represents a deeper inquiry than the spectacle of Sensation would imply.

1. Quoted in Jonathan Jones, “Paradise Reclaimed,” Guardian, magazine section, 15 June 2002.

2. Carol Becker, “Brooklyn Museum: Messing with the Sacred” in Chris Ofili, Rizzoli, 2009, p. 84.

3. Chris Ofili, quoted in Judith Nesbitt “Beginnings” in Chris Ofili, London: Tate Publishing, 2010, p. 15.

4. Chris Ofili, “Decorative Beauty was a Taboo Thing”, interview with Mario Spinello, Brilliant! New Art from London, exh. cat., Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 1995, p. 67.

Additional resources:

Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection (Brooklyn Museum)

Ofili at the Saatchi Gallery

Clarissa Rizal, Resilience Robe

by LILY HOPE AT PORTLAND ART MUSEUM and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Clarissa Rizal, Resilience Robe, 2014, merino wool, 64 x 53 inches (Portland Art Museum)

Bill Viola, The Crossing

We have to reclaim time itself, wrenching it from the “time is money” maximum efficiency, and make room for it to flow the other way – towards us. We must take time back into ourselves to let our consciousness breathe and our cluttered minds be still and silent. This is what art can do and what museums can be in today’s world.

—Bill Viola [1]

Taking time back

Bill Viola’s The Crossing is a room-sized video installation that comprises a large two-sided screen onto which a pair of video sequences is simultaneously projected. They each open in the same fashion: a male figure walks slowly towards the camera, his body dramatically lit from above so that it appears to glow against the video’s stark-black background. After several minutes he pauses near the foreground and stands still. He faces forward, staring directly into the lens, motionless.

At this point the two scenes diverge; in one, a small fire alights below the figure’s feet. It spreads over his legs and torso and eventually engulfs his whole body in flames; yet, he stands calm and completely still as his body is immolated, only moving to raise his arms slightly before his body disappears in an inferno of roaring flames. On the opposite screen, the event transpires not with fire but with water. Beginning as a light rainfall, the sporadic drops that shower the figure build up to a surging cascade of water until it subsumes him entirely. After the flames and the torrent of water eventually retreat, the figure has vanished entirely from each scene, and the camera witnesses a silent and empty denouement.

Expanded temporal experience

The Crossing makes use of Viola’s signature manipulation of filmic time. Like many of the artist’s recent works, it was shot using high-speed film capable of registering 300 frames per second, thus attaining a much greater level of detail than would be discerned by the naked eye. In postproduction, Viola reduces the speed of playback to an extreme slow motion—further enhancing the level of definition to a dramatic and scrutinizing effect.

However, it is not only an interest in technological experimentation that drives the artist’s technical and aesthetic decisions. Viola’s use of slow-motion is meant to invite a meditative and contemplative response, one that requires the viewer to concentrate for a longer duration of time and simultaneously to increase his or her own awareness of detail, movement and change. This is consistent with the artist’s intent to reignite the longstanding relationship between artistic and spiritual experience. A devoted practitioner of Zen Buddhist meditation, Viola has explained that after “fifty minutes of quiet stillness in a room of solitary individuals”—a description that could, just as easily, reflect a museum-goer’s experience of his installations—“time opens up in an unbelievable way.” [2]

Religious symbolism

The Crossing might be interpreted through the lens of mythology or religious thought, even though the work does not make iconographic or stylistic reference to a particular narrative. Viola has been inspired by a rich variety of spiritual traditions, including Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sufism. Viewers may recall, for instance, the ring of flames that surrounds images of Shiva Nataraja (left) in which he sets in motion the continuous cycles of creation and destruction through his cosmic dance, or the biblical tales of fire and brimstone, rapture and the Great Floods. Throughout such narratives, the elemental forces of fire and water often symbolize change, redemption, transformation and renewal— common themes in Viola’s oeuvre. The artist has similarly made reference to transitions and passages in works such as The Passing, a 1991 video made shortly after his mother’s death, or Two Women, a 2008 piece in which figures slowly move through a translucent and symbolic barrier of water.

Viola’s education and artistic practice have long been guided by questions of “how we see, how we hear, and how we come to know the world.” [3] The artist grew up in Queens, New York and attended Syracuse University in the late 1960s where he enrolled not only in fine arts classes, but also in a variety of academic subjects ranging from the humanities to the hard sciences. In particular, he was captivated by religious studies, psychology and electrical engineering, interests that are clearly assimilated throughout his oeuvre.

Technological experimentation

As early as the 1970s, Viola was one of the first visual artists to make use of new video technologies. As a student he experimented enthusiastically with new portable recording devices, with which he created short video performances that explored a variety of gestures, sounds and expressions. During the 1970s and 1980s, he was artist-in-residence at a number of media laboratories and television stations, while also serving as an assistant curator at Everson Museum of Art where he was exposed to the work of Nam June Paik and Peter Campus, artists who were early innovators in the emerging field of video art. Eventually, Viola conceived of multi-channel and immersive installations where viewers are surrounded by carefully arranged screens and projections, sometimes displayed within an otherwise pitch-black room.

Sacred space

Between 1974 and 1976, Viola lived in Italy, where religious paintings and sculptures are often displayed in-situ, in the cathedrals for which they were commissioned. The continuing integration of historical art into contemporary public and religious life inspired Viola to design installations that mimicked the forms of devotional paintings, diptychs, predellas and altarpieces—formats that encourage intimate contemplation of religious icons. Later traveling throughout Japan and other parts of East Asia, Viola observed the same active level of engagement with art. In Tokyo, for instance, he witnessed museum visitors placing offerings at the feet of sculptural bodhisattvas or other religious statuary.

For viewers, the experience of viewing Viola’s works need not be spiritually inscribed. In many cases, his works appeal to or reflect raw human emotions (the theme of his acclaimed exhibition The Passions) or universal life experiences. While The Crossing can be interpreted in light of a host of religious associations, the act of “self-annihilation” represented in the figure’s disappearance at each conclusion also serves as a metaphor for the destruction of the ego. In the artist’s words, this action “becomes a necessary means to transcendence and liberation,” [4] especially in the face of life’s inevitable unpredictability.

[1] Bill Viola, as quoted in Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art, Jacquelynn Baas and Mary Jane Jacob, eds. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), p. 254

[2] Bill Viola, Buddha Mind, p. 254.

[3] “Bill Viola Interviewed by John Hanhardt, Going Forth By Day (Berlin: Deutsche Guggenheim and New York: Harry N Abrams, Inc, 2005), p. 87.

[4] Bill Viola, as quoted in “Emotions in Extreme Time: Bill Viola’s Passions Project,” in The Passions, John Walsh, ed. (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003), p. 53.

Additional resources:

Bill Viola at SFMOMA

Bill Viola – James Cohan Gallery

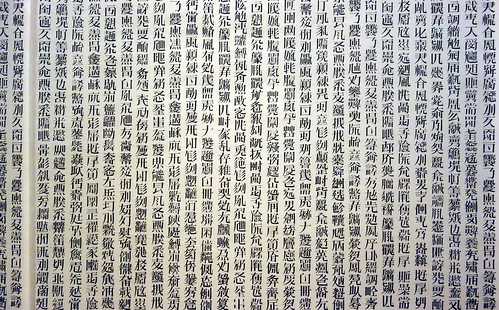

Xu Bing, Book from the Sky

by DR. ALLISON YOUNG and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

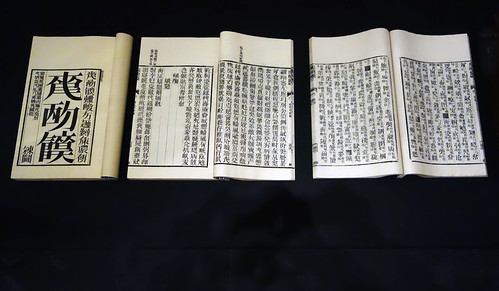

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Xu Bing, Book from the Sky, c. 1987-91, hand-printed books and ceiling and wall scrolls printed from wood letterpress type, ink on paper; each book, open: 18 1/8″ × 20″ / 46 × 51 cm; each of three ceiling scrolls: 38″ × c. 114′ 9-7/8″ / 96.5 × 3500 cm; each wall scroll: 9′ 2-1/4″ × 39 3/8″ / 280 × 100 cm (installation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014, collection of the artist) © Xu Bing

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

James Turrell, Skyspace, the way of color

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

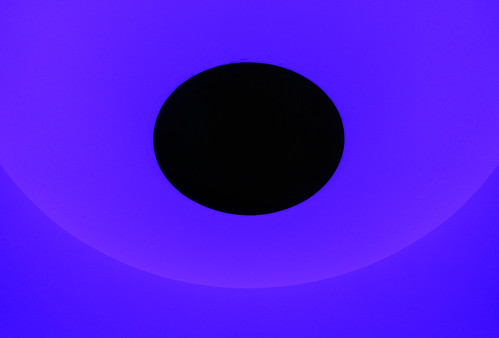

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): James Turrell, Skyspace, The Way of Color, 2009, stone, concrete, stainless steel, and LED lighting 228 x 652 inches © James Turrell (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Tenzing Rigdol, Pin drop silence: Eleven-headed Avalokiteshvara

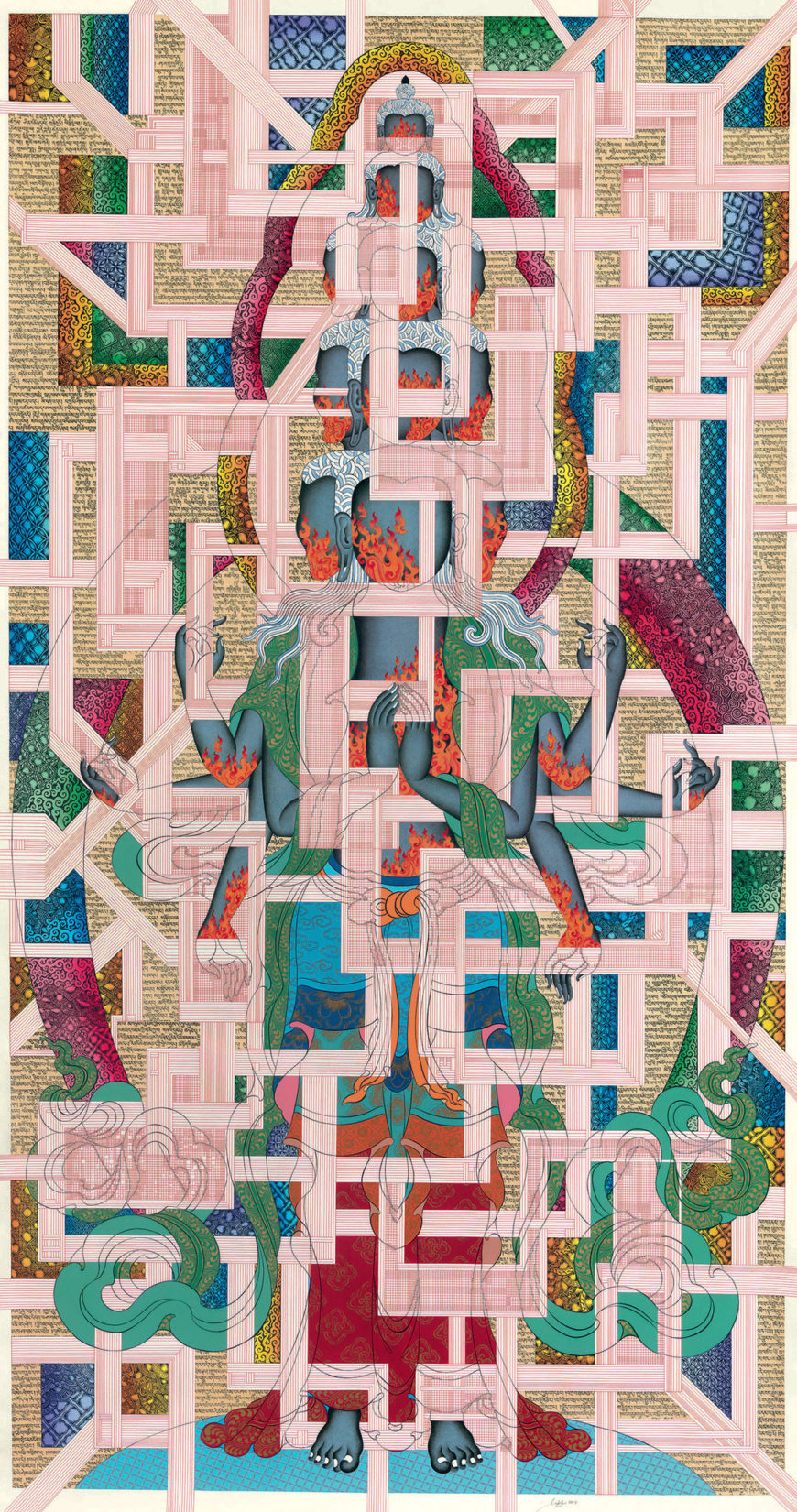

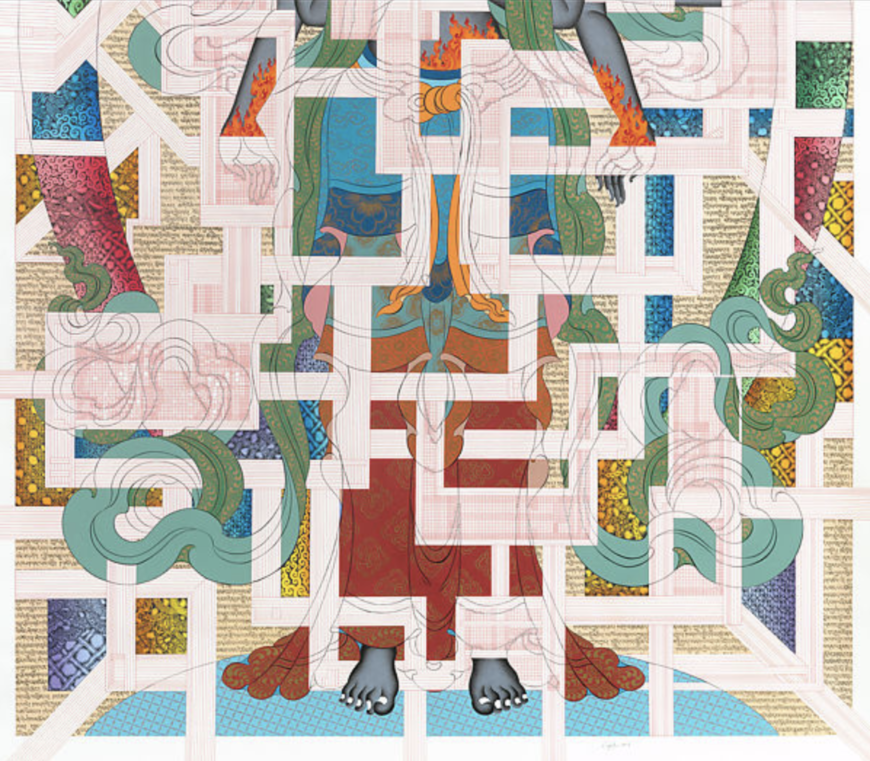

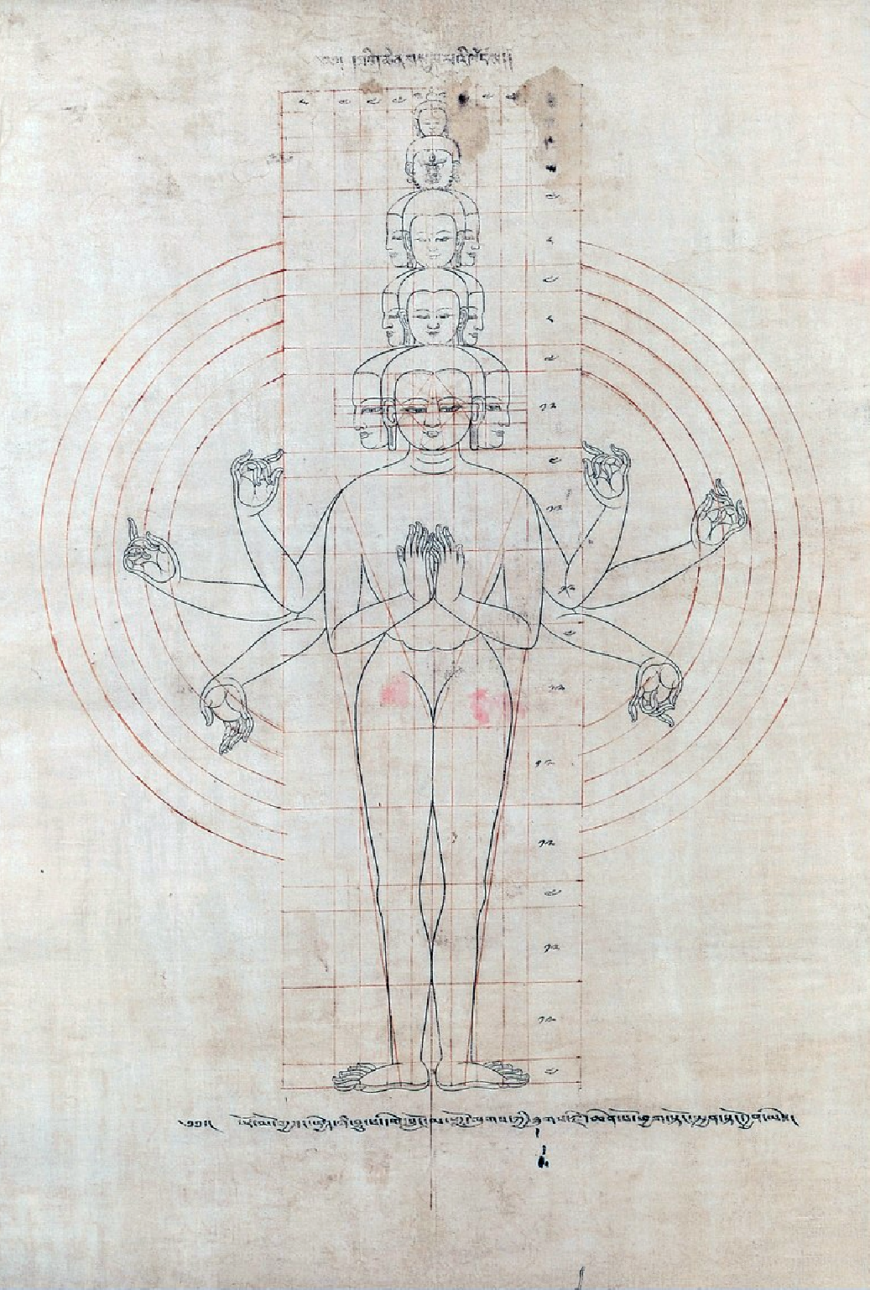

In Tenzing Rigdol’s monumental painting, Pin drop silence: Eleven-headed Avalokiteshvara, we encounter a traditional Buddhist deity—though the artwork itself is anything but conventional in form, material, or meaning. Rigdol uses a combination of acrylic paint, pastel, and pieces of manuscript pages assembled on paper to create a complex rendering of a multi-armed, multi-headed deity—over seven feet tall—who emerges between the interlocking edges of a grid-like overlay. Although the main figure is one that is recognizably sacred for Tibetan Buddhist practitioners, the work itself constitutes a radical departure from historical precedent, and reflects contemporary questions surrounding exile, activism, and cultural heritage.

Rigdol was born in 1982 in Kathmandu, Nepal. His parents fled Tibet in the late 1960s and worked in Nepal’s carpet industry. After training in traditional Tibetan arts, including thangka painting (a painting on fabric depicting a Buddhist subject), sand painting, and butter sculpture, the artist turned to contemporary modes of representation. He is one of the first contemporary Tibetan artists to have his work collected by major institutions, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art. By using culturally specific forms in radically new compositions, Rigdol shifts his work’s focus away from the spiritual symbolism often associated with Tibetan art, and towards more politically charged content.

Who is Avalokiteshvara?

In the center of Pin drop silence is the Buddhist deity known as Avalokiteshvara (Tibetan: Chenrezig). Avalokiteshvara is a bodhisattva (an enlightened being who helps others achieve enlightenment) and is the embodiment of compassion. Avalokiteshvara remains a major figure in Buddhist art throughout Asia (he is known as Guanyin in China). The Dalai Lama is viewed as the earthly incarnation of Avalokiteshvara by practitioners, and as such, plays an important role in Tibetan Buddhism.

In Pin drop silence, Avalokiteshvara is shown in his eleven-headed form, a reference to his head splitting into several parts in order to more fully observe the world and disseminate compassion. Unlike traditional imagery of Avalokiteshvara, however, none of Rigdol’s Avalokiteshvara’s heads are given a face. For orthodox Tibetan Buddhist practitioners, this omission is significant; buddhas and bodhisattvas are traditionally drawn with very specific guidelines and gridlines in place, including precise renderings of facial features. Here, Rigdol omits these features and seemingly splits the image into pieces with his use of gridlines.

Guidelines and Gridlines

In traditional Tibetan Buddhist painting known as thangka, gridlines were (and are) used as guides to ensure the proper placement and depiction of buddhas (of which there are many, not just the historical Buddha Shakyamuni) and bodhisattvas. The lines are the first step of the process, and they are ultimately covered by the paint—they function merely as guidelines for the artist. Yet Rigdol makes gridlines a major component of Pin drop silence. They divide the image, deconstructing the form of Avalokiteshvara through their presence.

Rigdol has referenced his early work as a carpet designer in Nepal as an additional point of reference for these gridlines (the design process for carpets uses a matrix as well). Further, some scholars have noted similarities between Rigdol’s affinity for grids and lines and those of the modernist De Stijl artist Piet Mondrian, for whom geometric abstraction held spiritual or utopian value. [1] Rigdol says this about the lines:

Lines are innocent, direct and uncompromising. There is a sense of contentment within the geometric forms. They exert no pressure on me, but instead pull me towards them to look closer. [2]

Replacing the Background

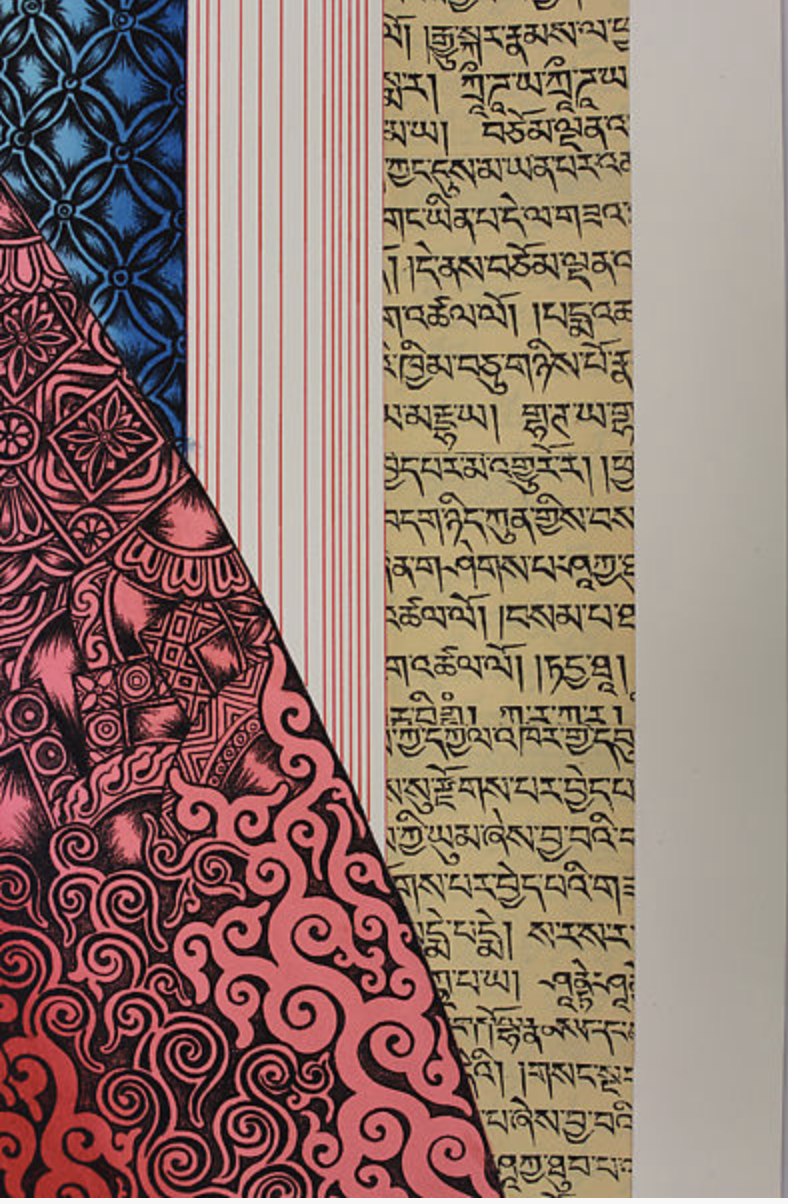

The gridlines in Rigdol’s work are constructed from intersecting fragments of manuscript pages, which hold a personal meaning for the artist. Rigdol’s family had been in business as ink manufacturers in Tibet prior to their escape to Nepal in the late 1960s. This ink was used by monasteries to print the Buddhist manuscript pages used by monks, nuns, and lay Buddhist practitioners.

The script on these pages is known as u-chen, and is utilized across the Tibetan plateau. (Though the dialects differ across the region, this script can be read by many Tibetans). In traditional Tibetan thangka, the backgrounds often incorporated influences from Chinese landscape painting. By “replacing” that landscape with the unifying Tibetan script, Rigdol reimagines “tradition,” questioning the role of Chinese landscape painting in the history of Tibetan art.

As he notes:

Historically, the landscape elements in Tibetan thangka painting—the clouds, the rivers and so on—were influenced by Chinese painting. They later got an upgrade in Tibetan art. I have often said, sometimes jokingly and sometimes seriously, that in adopting Chinese style landscapes in their paintings, Tibetan artists of the past were foretelling the colonization of Tibet’s land, sky, rivers and mountains by the Chinese. In 1959, when Tibet lost its country, the prophecy was fulfilled. [3]

In this passage, Rigdol refers to a series of events in the 1950s that established Chinese rule over Tibet. There exist two opposing narratives about this period: the Chinese government and Chinese history books refer to it as the “Peaceful Liberation of Tibet,” whereas Tibetans view the period as a devastating takeover of their land by colonizing forces, the “Chinese invasion of Tibet.” Although many decades have now passed, there is still great strife in the region (now called the Tibet Autonomous Region, or TAR), resulting in ongoing political protests and efforts to silence dissent.

Representing self-sacrifice

Rigdol incorporates flames throughout the body of the deity, a reference to the ongoing self-immolation by Tibetans. Since 2009, 156 Tibetans have publicly protested the rule of the Chinese government by setting themselves on fire, often resulting in death. [4]

Another work by Rigdol, My World Is in Your Blind Spot, incorporates these flames. This work is a direct reference to the lack of attention that these devastating protests have had in the international community. My World Is in Your Blind Spot is a series of five works that shows buddhas in meditative postures, with flames appearing within the contours of their bodies. Rigdol photographed the flames and then cut the images apart before reassembling them, claiming a preference for a “calm” and dignified flame rather than an aggressive flame to honor the sacrifice of so many Tibetans. The casual viewer of Rigdol’s work is likely unaware of these protests. While the panels are beautiful to look at, they are devastating to comprehend. This political statement would not be permitted in the Tibet Autonomous Region because of strict censorship imposed by China, instead it was made in exile.

Rigdol is one of many contemporary Tibetan artists who has never set foot in Tibet. In exile communities scattered around the world, artists have established a visible global presence by creating group exhibitions such as Waves on the Turquoise Lake (2006), Traditions Transformed (2010) and Anonymous (2013–2015), all of which showcased work by artists located both in the Tibet Autonomous Region and those working in exile communities. Many of these artists incorporate Buddhist elements in their work, although in some cases this inclusion is more of a nod to a cultural connection than to religious identity (artists may or may not be Buddhist practitioners, and the work in these exhibitions was rarely meant to function in a sacred manner). Yet, the relationship to Tibet is firmly established, as it is in Pin drop silence: Eleven-headed Avalokiteshvara.

Notes:

[1] Francesca Gavin, “The Construction of Harmony,” Tenzing Rigdol: Experiment with Forms exhibition catalog (Rossi & Rossi Ltd., 2009), p. 9.

[2] Gavin, “The Construction of Harmony,” p. 9.

[3] Interview of Tenzing Rigdol by Fabio Rossi, 2015 Accessed August, 2018.

[4] The International Campaign for Tibet lists the current number of self-immolations at 156, though the actual number may be higher, “Self-immolation Fact Sheet”

Additional resources:

Kurt Behrendt, “Tibetan Buddhist Art in the Twenty-First Century” (March 12, 2014)

Sarah Magnatta, “Between the Lines,” Tenzing Rigdol: Dialogue, exhibition catalog (Rossi & Rossi Ltd., 2019).