12.9: Cultural heritage endangered round the world

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147876

Cultural heritage at risk: Mali

by SAFE (SAVING ANTIQUITIES FOR EVERYONE)

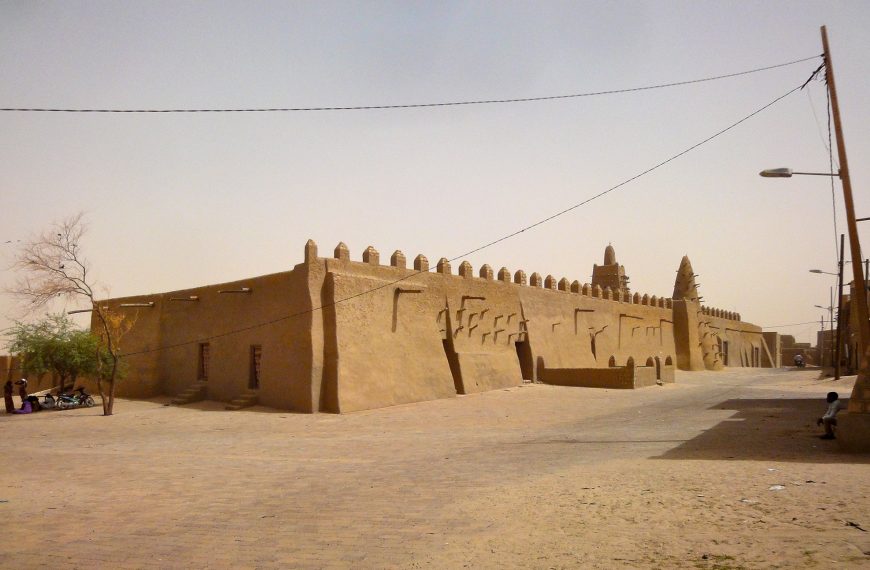

Internal conflict has had a disastrous impact on Mali’s rich archaeological heritage in recent years. In 2012, Tuareg and Islamic separatists took over northern Mali, destroying crucial works of Malian heritage (AllAfrica). The historic sites of Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal all experienced extensive damage.

According to UNESCO, “Fifteen of Timbuktu’s mausoleums were destroyed, including nine that are part of the World Heritage sites. We estimate that about 4,200 manuscripts from the Ahmed Baba research centre were burned, and that another 300,000 in the Timbuktu region are vulnerable to illicit trafficking.”

The devastating impact of conflict and civil strife on internal heritage is clear in this instance and further underlines the need to work together to help Mali protect its heritage.

What is at stake for Mali?

The numerous great civilizations of Mali have left behind a rich archaeological record spanning from the Neolithic period to the 18th century. The Niger River Valley hosted a crossroads for culture and commerce based around the trans-Saharan trade, which exchanged gold, ivory, salt, and slaves for products from the Mediterranean and Middle East. Cities such as Gao and Timbuktu rose as great centers of commerce and learning during the medieval period, boasting splendid mosques and Islamic architecture as well as the tomb complex of the emperor Askia Mohamed. Bamako became an important commercial center later in the 17th century. Settlement at Djenné-Jeno, an important trading center, covered more than 16 centuries. Occupation here has left behind an archaeological mound over five meters thick, which has provided valuable information on the emergence of trade and social complexity at this site.

Unfortunately these rich cultural resources have proven too great a temptation for looters. Mali has suffered from looting since early colonial officials collected artifacts as souvenirs, but the problem became truly serious starting in the 1970s when a series of droughts drove poor farmers to seek other sources of income. These droughts happened to coincide with the discovery of terracotta figurines at Djenné (Sanogo, Sidibé 1995). Looting activity increased significantly after this point, so that now estimates place the number of sites looted in the Niger River Valley at between 80 and 90%. The plundering varies from individuals collecting random artifacts exposed at the surface to the mass destruction of entire sites by groups of laborers digging holes and trenches. The archaeological mounds at Kané Boro, Hamma Djam, and Natamatao have all been ransacked by looters who destroyed the sites with trenches and shafts.

Meanwhile, the international antiquities market has taken a keen interest in objects from Mali. Zoomorphic statuettes in terracotta, beads, copper vessels and jewelry, and iron figurines are among some of the items sold regularly in auction houses, at dealer’s galleries, and even online. Thanks to looting, the number of objects flooding the market is large, while our knowledge of Mali’s ancient heritage remains extremely limited.

What Mali is doing to protect its cultural heritage

In response to the widespread damage caused by looting, the government of Mali took action to protect its cultural patrimony with a series of laws and decrees passed between 1985 and 1987. These statutes aim to protect and promote the cultural heritage of Mali, regulate excavations, and control the export and commercialization of cultural property. Included in these laws is a provision which states artifacts leaving the country must be accompanied by an export license from the Cultural Heritage Services at the National Museum in Bamako. Mali also ratified the 1970 UNESCO Convention in 1987, showing its support in regulating the traffic of illicit artifacts worldwide. In addition to this legislation, the government of Mali has striven to educate its officials and the general public, raising awareness of the looting problem.

Programs focused at the local level have utilized radio, television, meetings, traveling exhibitions, and even staged plays to get the message across and encourage involvement (Sidibé 2001). Cultural missions were established at Djenné, Bandiagara, and Timbuktu in 1993. In some areas, the success of these efforts has turned would-be looters into custodians of cultural heritage—villagers are founding museums and working to protect and preserve Mali’s archaeological treasures in the Mopti region and near Djenné-Jeno (Sidibé, 2001). On a larger scale, the National Museum of Mali at Bamako has made outstanding efforts to protect cultural property and to advance an understanding of history—not just for Mali, but for Africa as a whole.

Just last year the museum was presented with the Prince Claus Fund Award for promoting cultural heritage and cultural exchange. The country also participated in workshops organized by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) in Arusha, Bamako, and Kinshasa. Museum professionals, law enforcement officers, customs officials, archaeologists, and other professionals all collaborated at these workshops in order to reach a better understanding between countries of import and export.

What other countries do to aid Mali’s cause

Mali’s internal efforts demonstrate that the country has taken positive action to protect its cultural patrimony, but unfortunately it is not enough to stem the tide of looting and the illicit trade. Although the country has taken great initiative in the battle against looting, as a developing nation, Mali has limited resources for the protection of archaeological sites and the policing of its borders (McIntosh, 1995). Even so, the nation dedicates an admirable portion of its meager budget towards these efforts. So long as there is an international demand for Malian artifacts, there will be a need for international cooperation to combat looting.

Thankfully, other countries are collaborating with Mali to show their commitment to preserving the world’s cultural heritage. In 2005 Norway launched a UNESCO Funds-in-Trust project to aid the countries of Mali, Ethiopia, and Senegal. This project aims to preserve and document archaeological collections and archaeological sites, raise awareness of the looting crisis, and educate local officials and the public. ICOM, whose members include institutions from across the globe, has drafted a “red list” for Mali of categories of artifacts that are most affected by looting. ICOM appeals to museums, collectors, dealers, and auction houses not to buy these objects and provides information on the legislation protecting them. Preventive measures such as these attempt to decrease the overseas demand for stolen artifacts, and they are helpful and necessary. In January of 2007, French customs officials seized more than 650 artifacts from Mali being smuggled through the Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris. These objects were presumably on their way to the U.S., where they would be sold to dealers and private collectors. Such instances demonstrate the need for U.S. cooperation to combat the looting problem. Thankfully, the MoU between the United States and Mali was renewed in 2012.

How does Mali continue to share its culture without endangering its resources?

These endeavors show that restricting the illicit trade of artifacts does not prevent cultural exchange between nations. On the contrary, it has led to international collaboration and new efforts to educate and spread culture between nations. The traveling exhibition “Vallée du Niger” opened in Paris in 1993 and visited numerous African countries. In 2003, the Smithsonian Festival of Folklife put on an immense exposition of Mali’s culture featuring music, dancing, food, films, arts, and even the appearance of Amadou Toumani Toure, president of Mali. Numerous universities throughout the United States also boast study abroad programs in Mali, including Harvard, Michigan State, Drew University, and Antioch College. Examples such as these show that Mali’s cultural heritage can be part of the world’s cultural heritage through positive forms of exchange.

Cultural heritage at risk: Peru

by SAFE (SAVING ANTIQUITIES FOR EVERYONE)

Peru’s cultural heritage is extensive and diverse, including important sites and artifacts from the ancient civilizations of the Moche and Nazca. Although national and international legislation exists in order to protect the country’s heritage, it is largely ineffectual due to the wide scope and the lack of sufficient funding to protect sites and enforce laws (as is often the case). The gravity of the current circumstances was evident in the aftermath of the Greenpeace protest of December 2014, where activists trespassed on the country’s historical Nazca lines during a publicity stunt intended to send a message to the UN climate talks delegates in Lima.

In the wake of the Nazca lines scandal, Peru’s Minister of Culture stated that “more than 1,000 of Peru’s archaeological sites are at risk for lack of security and resources to guard the sites.” According to the Minister, “It is impossible for the Ministry of Culture, with the resources it has, to keep guard of thousands of archaeological sites or 5,500 kilometers of the Nasca Lines.”

Nevertheless, this is not the first time Peru’s heritage has been damaged by avoidable circumstances. The world-renowned sites of Machu Picchu and Chan Chan have faced extensive damage due to their popularity as a tourist attraction. Moreover, “in 2000, an Incan solar clock was damaged during the filming of a commercial, while a quad bike left marks on a candelabra geoglyph in nearby Paracas in 2010.” Likewise, in 2013 it was reported that heavy machinery had defaced a group of the Nazca lines and the Paris-Dakar rally damaged parts outside of the World Heritage area. Such distressing events point to the need for much greater cultural heritage protection and awareness.

Vandalism and invasion are not alone in threatening Peru’s archaeological sites. Another great risk is the pervasive looting and illicit digging occurring throughout the country.

Between 2004 and 2006, illicit exports of over 5,000 cultural and natural objects were intercepted. Nevertheless, the number of clandestine excavations at archaeological sites has increased, as have thefts from churches and museums. Illicit trade in Peruvian cultural property causes irreparable damage to the country’s heritage and identity, and constitutes a serious loss for the memory of mankind. (ICOM)

What is at stake for Peru?

Looking across the Peruvian desert, you can imagine it is a moonscape pocked with craters as far as the eye can see, except the holes are looted tombs. Royal tombs that once contained gold, silver, and copper ornaments have been stripped without any care for the cultural information their scientific excavation could reveal. Today you can find authentic Chimu and Nazca pottery being sold on eBay, dug up by rural peasants looking for objects like the ones in the Sotheby’s catalogs.

Visitors from around the world flock to sites like Machu Picchu every year to witness firsthand the magnificence of the Incan civilization. Tourism is the third largest industry in Peru, and its cultural sites and museums are major attractions. The looting of archaeological sites and the removal of objects from Peru are negatively impacting tourism. Preserving archaeological ruins and returning artifacts for display in on-site museums is mutually beneficial to the local population and foreign visitors who share an interest in our global heritage.

Looters did not return to the place now because there was nothing left….In the last two decades of the twentieth century…more Andean historical heritage was lost than in the previous four centuries….

– Roger Atwood writes about the Andean site of Chilca, Peru, in Stealing History

Looting continues in Peru

Looting and illicit antiquities trafficking continues despite protective measures both in Peru and abroad. Thankfully, U.S. import restrictions have resulted in the confiscation and return of many artifacts to Peru, including 18th century religious artifacts stolen from churches and thousand-year-old human skulls torn from their graves. According to the International Council of Museums’ Red List of Peruvian Antiquities at Risk, over 5,000 looted objects were seized between 2004 and 2006 thanks to the MOU.

In one of the largest busts of trafficked antiquities, U.S. Customs seized 412 pre-Columbian artifacts—including silver masks, Inca quipus, and effigy vessels—from an Italian art thief and returned them to Peru in 2007. Since 2010, U.S. Customs has intercepted and returned to Peru the above-mentioned pre-Columbian human skulls and 18th century manuscript, Inca pottery, Moche sculpture, and textiles. In 2011, a Moche gold bead in the shape of a monkey head in the Museum of New Mexico’s Palace of the Governors was returned to Peru after it was identified as having been illegally removed from the royal tombs of Sipán.

What is Peru doing to protect its cultural heritage?

In 1990, extensive digging by tomb raiders prompted the government of Peru to request that the U.S. impose emergency import restrictions on certain Moche artifacts from Peru’s northern coast. In 1997, the U.S. entered in to a bilateral agreement with Peru which placed import restrictions on pre-Columbian archaeological artifacts and Colonial ethnological materials from all areas of Peru and continued the 1990 emergency action import restrictions on archaeological material from the Sipán region. The MOU was renewed in 2002, 2007, and again on June 9, 2012.

In June, 2013, the New York Times reported the Ministry of Culture’s program to block antiquities being smuggled out of the country, many of them bound for the U.S.

Incan artifacts that were scientifically excavated from Machu Picchu and temporarily curated in Yale’s Peabody Museum with Peruvian governmental permission are now being repatriated. Facilities to properly store and publicly display these objects within Peru are expanding, and professional training of Peruvian archaeologists and heritage specialists continues to increase. The collection will be returned to the International Center for the Study of Machu Picchu and Inca Culture by the end of 2012, and the people of Peru and tourists who visit Cuzco and Machu Picchu will be able to view them in a new site museum.

The U.S. Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation has contributed to several museum conservation and analysis projects in Peru. Security and public access continues to improve in Peruvian museums, as do conservation and climate-controlled displays for fragile textiles and mummies.

Peru is committed to sharing its rich past with the world through cultural exchanges with a growing emphasis on exchanges between museums. Peruvian objects have been loaned for the purpose of international exhibition, including 253 rare Incan gold ornaments on loan from Peruvian museums on display at the Pinacothèque de Paris museum in 2010. To commemorate the 20th anniversary of bilateral relations between Peru and South Korea, 351 artifacts from nine museums in Peru were exhibited in 2009 at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul.

Cultural heritage at risk: Turkey

by SAFE (SAVING ANTIQUITIES FOR EVERYONE)

The modern state of Turkey is one of the most archeologically and culturally rich places in the world; scholars have published on over a hundred thousand sites across the country (Özdoğan 2013). It boasts 15 sites of cultural importance on UNESCO’s World Heritage list, and has 60 additional sites under consideration. Despite the identification of and reporting on thousands of sites, only about 11,000 are officially registered with the Turkish government. Registration is critical to the preservation and protection of sites; without it, they can be destroyed during new building projects and land development.

The struggle to protect sites from modern building and development is the result of limited resources and personnel. With thousands of sites awaiting the attention of the government, employees of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism are fighting a never-ending battle. In addition to examining new sites and excavations, they must also maintain officially registered sites which are threatened by an explosion of tourism. Developing heritage management plans for these sites is critical, but time consuming as well.

While many of Turkey’s own antiquities have been and continue to be looted today, it has become a highway for illicit antiquities coming from its turbulent neighbors, Syria and Iraq.

What is at stake for Turkey?

Turkey, located within the region of Anatolia, has been home to many diverse modern, historical, and ancient cultures, and its history captures the breadth of the modern human experience.

Caves and western coastal sites dating to the Paleolithic (~400,000–14,000 B.C.E.) and Mesolithic (~14,000–10,000 B.C.E.) periods contain evidence for the earliest human presence in Anatolia.

The Neolithic period (10,000–5,000 B.C.E.) is well represented and is known internationally for several important sites. Catalhöyuk, in southern Turkey, is the largest and best preserved Neolithic site. Reaching its peak around 7,000 B.C.E., the site has evidence of plant and animal domestication and large permanent settlements. At the site of Göbeklitepe, in the southeast, archeologists uncovered a mountain-top sanctuary dating to around 9,000 B.C.E., making it the oldest identified religious structure in the world.

Across Turkey during the Chalcolithic (5,000–3,000 B.C.E.) and Bronze (3,000–1200 B.C.E.) Ages there is abundant evidence for the early development of metal processing, trade, and production. Increasing economic and social complexity led to a rise in urbanism and the development of massive centers, such as Hattusha, the Hittite capital. On the western coast, inhabitants during this time came into greater contact with other Mediterranean cultures, such as the Minoans of Crete and the Greeks. One of the most famous of these settlements is ancient Troy, which was famously under siege by the Greeks in Homer’s Iliad and later looted by Heinrich Schliemann’s nineteenth-century explorations of the site.

In later historic periods, many diverse cultures inhabited Anatolia and later the political state of Turkey influencing its landscape and the history of the states around it. Numerous societies, including the Urartians, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, and Lycians, established or conquered other kingdoms in Anatolia and are known through both archaeological and textual sources. With the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great, Anatolia came under Greek influence ushering in the Hellenistic Period (4th–1st century B.C.E.). Later the Roman Empire (1st century B.C.E.–4th century C.E.) absorbed Anatolia, marking another cultural transformation and historic events that would lead to the founding of the Byzantine Empire (395–1453 C.E.) based in Constantinople, modern Istanbul. Medieval and modern successors to this rich history of Anatolia include various Turkomen tribes, the Seljuk Turks, the Ahlatshahs and Artuquids, and eventually the Ottomans.

Turkey’s cultural heritage endangered

Understaffed/Underfunded

Turkey has many laws that protect its cultural heritage, however, the abundance of ancient materials has essentially overburdened government agencies, which often lack the resources and manpower to enforce the laws and preserve these sites.

Some of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s own policies inadvertently work against protecting sites. For example, even though a scholarly publication may be available for an excavated site, it is not enough for it to gain official registry with the government; instead, a member of the ministry must visit the site and re-document its findings (Özdoğan 2013). Employees are often overburdened already, and the time and resources for this type of documentation are highly limited.

Likewise, rescue excavations of sites threatened by modern development can only be conducted by museums and universities, who are also understaffed for this additional research, because contract archeology is not recognized by the government (Özdoğan 2013). This limitation can lead to hurried or only partial excavations of sites that may contain thousands of years of human occupation.

Modern Construction and Development

Turkey’s past and present are constantly confronted with one another; negotiating the rights of its modern citizens while protecting the past is one of its greatest challenges today. Some recent examples of modern activities that threaten the integrity of archeological sites include farming and pasturing near archeological sites, flooding large areas of land after the building of dams in the east, and the construction of new roads and buildings. The latter are major problems within modern Istanbul, which is experiencing a population boom that strains the resources and infrastructure of the city.

In 2004, plans for a new metro and light rail system in Istanbul were initiated to alleviate some of the traffic in the city. Keeping in mind the rich archaeology underneath the city, the subway was to be drilled into the bedrock to avoid disturbing potential sites. The project was approved, but neglected to consider the need for ventilation shafts and stairs to reach the metro lines, the digging for which would likely uncover sites and features. Sites were inevitably uncovered and unforeseen rescue excavations led by the Istanbul Archaeology Museum took place across the city, temporarily delaying the metro project, for several years in some areas (Özdoğan 2013). Pressure from the public and government forced these excavations to be conducted at a more rapid rate than normal. While the excavations were successful, it is clear that modern infrastructure was more a pressing issue than the archeological sites beneath the city. Almost any building projects in Istanbul are likely to face similar challenges in the future.

The Yedikule Gardens have been a fixture in Istanbul since the Byzantine Era and continue to be used by local residents as urban vegetable gardens. A portion of the gardens are surrounded by massive city walls built under Theodosius II in the 5thcentury C.E. and are a protected UNESCO heritage site. In 2013, plans were underway to transform part of the gardens into an urban park with a decorative pool. Demolition of the area began without warning, destroying the vegetable gardens of local inhabitants, and deep digging near the ancient wall damaged its foundation and stability. Archeologists from the Istanbul Archaeology Museum intervened, arguing that this was a protected area, the project was unearthing and destroying Ottoman and Byzantine archeological materials, and the excavations should proceed under their guidance to ensure no further damage is done (White et al. 2015). Luckily, in a July 2015 court decision, development in and near the gardens was halted indefinitely.

Similarly, the garden associated with the 16th-century Piyalepaşa mosque was also under threat recently (as of August 2015). Plans to turn the space into a parking structure were halted temporarily and are under review. The garden was conceived by the original architect of the mosque and was regarded as essential to the intended use and experience of the space.

Tourism

While positive in many aspects, the increasing tourism across Turkey threatens the preservation of archeological sites. The growing number of visitors annually (at some sites numbering over a million a year) results in greater demand for lodging, food, and transportation near sites. Providing such services has inevitable impacts on archeological sites as well as the surrounding environment (Serin 2005). Offering lodging for tourists wishing to visit an archeological site requires building near the site. Often just a portion of a site is visible with much of it remaining unexcavated; without proper survey prior to new building, the unseen areas of sites can easily be damaged or completely destroyed.

Additionally, without proper heritage management plans the sites can be damaged by visitors walking on or around fragile areas compromising the integrity of structures. The lack of resources and personnel leave some sites completely unattended and unprotected from damaging behavior by visitors and may increase the possibility of looting by thieves.

Market demand for Turkish antiquities

The looting and sales of antiquities from Turkey is an ongoing problem as many sites are left unprotected or have not been fully excavated. Established networks of looters, smugglers, middlemen, and buyers transport antiquities out of the country. The destination for many of these antiquities is Switzerland where artifacts are housed, sometimes for several decades, before appearing on the market to buyers in Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The Syrian Conflict and the destruction by ISIS, currently devastating the archeological landscape in neighboring Syria and Iraq, are escalating the transport of illicit antiquities through Turkey. Civilians are left jobless and desperate to support their families, and the readily available archeological materials have become a primary source of income. Objects looted from these sites are often smuggled into Turkey and sold to Western buyers.

Ancient coins, cylinder seals, and cuneiform tables are highly prized from sites in Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. They are easy to conceal and transport and are a favorite amongst collectors. Additionally, pre-Islamic figurines are desirable as art pieces and are also relatively easy to transport.

What is Turkey doing to protect its cultural heritage?

Turkey has a long list of laws to protect archaeological sites and artifacts from destruction, looting, and illicit sales (UNESCO Database of National Cultural Heritage Laws–Turkey). Its most important, the Law on the Protection of Cultural and Natural Property, was enacted in 1983 as a form of blanket legislation, which declares that all antiquities found and not yet found within Turkey are property of the state; therefore, antiquities found within its borders are illegal to export. With this type of law, any object that is removed from its borders is considered stolen property; it does not, however, apply to antiquities discovered beyond its borders meaning illicit artifacts traveling through Turkey are not subject to these laws.

Turkey has used this type of blanket legislation to sue foreign museums for the return of items they believe to have been looted from sites within its borders. In the case of the Lydian Hoard, Turkey took legal action against the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to recover a collection of 363 artifacts, which they believed to have been looted from burial mounds in the Manisa and Uşak regions of Turkey in the 1960s. The assemblage, which included gold and silver vessels and jewelry, wall paintings, and a pair of marble sphinxes, was hidden from the public until about 25 years after they were acquired by the museum. Through comparison of other materials found in the burial mounds and interviews with the original looters, Turkey was able to prove that the objects were indeed stolen, and the Met subsequently returned them.

Çatalhöyük after the first excavations by James Mellaart and his team (photo: Omar hoftun, CC: BY-SA 3.0)Today, archeologists and scholars are working to develop heritage management plans for many sites across Turkey. Plans to protect world-famous sites, such as Cappadocia, are underway with support from the international community. Japan’s Funds-in-Trust for the Preservation of World Cultural Heritage, in cooperation of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, is investing $1.2 million to protect the Rock Sites of Cappadocia. The project focuses on protecting 22 painted rock-hewn churches and making the area more sustainable for tourism while promoting international cooperation.

Cultural heritage at risk: Syria

by SAFE (SAVING ANTIQUITIES FOR EVERYONE)

Syria, home to some of the oldest and culturally rich cities and archaeological sites in the world, is currently experiencing significant devastation. Damage has been reported at all of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Syria, and this is only the tip of the iceberg. Not only is direct shelling and military occupation a huge issue but additionally the breakdown in order often leads to widespread looting, as well as cases, as we have seen recently, of iconoclasm.

The situation has worsened since Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) jihadists, whose strict Salafi interpretation of Islam deems the veneration of tombs and non-Islamic vestiges to be idolatrous, seized swathes of Syria and Iraq in recent months, destroying sites and burning precious manuscripts and archives. (Al-Akhbar)

Legions of ancient sites in Syria have been destroyed, damaged, or looted throughout the enduring conflict according to new satellite imagery.

UNITAR found that 24 sites were completely destroyed, 189 severely or moderately damaged and a further 77 possibly damaged.

Moreover, shocking stories of ancient citadels taken over by military factions are reported frequently and further damage constantly. Widespread looting has been reported at sites throughout the country, most notably, at Palmyra. The current situation in Syria highlights the plight of cultural heritage in countries exposed to warfare and political instability.

Syria’s cultural heritage endangered

Near eastern archaeology is arguably one of the most developed in the world. Longstanding research traditions have helped highlight the role of this area within major phases in the (pre)history of mankind. This has led to the development of archaeological and preservation/conservation projects through the collaboration of international and local teams. In Syria, almost every archaeological period is represented by a range of sites (more than 6,000 were recorded in 2010), each contributing in their unique ways to our understanding of the past. Archaeologists have witnessed evidence of Lower Paleolithic, modern humans walking out of Africa, the development of early agriculture, irrigation systems, urbanism, and writing systems, in places such as ‘Umm el Tlel, Abu Hureyra, Hamoukar, Ebla, Palmyra and Damascus. The country also currently has 6 UNESCO World Heritage sites: Damascus (1979); Palmyra (1980); the ancient city of Bosra (1980); Aleppo (1986); the Crac des Chevaliers and Qal’at Salah El-Din (2006); and the ancient villages of Northern Syria (2011).

According to Bruce G. Trigger in his book A History of Archaeological Thought, published in 2006, most Arab and Muslim countries have created complex bureaucratic systems in order to protect their cultural heritage. In Syria, the legislation regarding the antiquities defines issues such as ownership and compensation as well as the features which constitute an “antiquity” in the first place (i.e. any goods manufactured, produced, written, or drawn that are more than 200 years old as well as any other goods that would not fit this category but would have an important historical status). These objects cannot be owned by individuals and are the inalienable property of the State. The Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM) provided an officious structure for the preservation and study of this material. However, there are some issues partly inherent to the nature of this kind of structure. The lack of security in some of the regional museums, the limited inventories, and, in general, the poor documentation of the collections lead to unsteady situations in times of trouble, which put the cultural heritage of these countries in great danger (as already seen in Lebanon in 1978 and 1982, or again, in Hama, Syria, in 1982).

Several associations/organizations (see Appel à la préservation des musées syriens adressé aux institutions internationales et à la communauté internationale) have been keeping track of the damage done to cultural heritage since the beginning of the unrest. They all emphasize the danger of underestimating the threat under which cultural heritage currently finds itself. The collective Patrimoine Syrien en Danger (PAS) comments in a letter, dated 07/07/2011 (document #9575/1) and addressed by ‘Adel Safar, to each of the different ministries. Here ‘Adel Safar mentions that the country’s heritage is at risk of looting from specialized and highly trained groups aiming at ancient documents and artifacts. The collective suggests that this letter was using the danger of looting to legitimate some of their military actions, thus instrumentalizing Syria’s patrimony.

More recently, the Institute for the Study of War has issued regular situation reports on military activities throughout Syria. Widespread conflict leading to sustained instability in the country has jeopardized the safety of its most precious cultural heritage sites.

Actual damages can be broken down into different categories and vary in degrees of degradation. These range from the simple graffiti on a Roman temple at El Dumaier to the destruction of Qalaat el Mudeeq. An extensive report found on the Global Heritage Network, provided by Emma Cunlife from Durham University on May 16th 2012, lists most of the destruction known to us. In addition to this report, most of the sources available to us come from the Facebook group Patrimoine archéologique Syrien en danger where Syrian individuals share articles and Youtube videos of the destruction of material heritage. Only some of the videos are shared, but they can be viewed here. Some of this information has also been directly confirmed by independent sources in Syria.

The devastating effects of looting in Syria

This category encompasses illegal excavations as well as antique thefts and more generally summarizes any harm done to cultural heritage for commerce purposes. Following ‘Adel Safar’s letter, some governmental forces seem to have moved parts of the Der’a, Alpe, Quneitra, Hama, and Homs museum collections either to Damascus and/or to some other unknown locations. In this situation, the risk represented by the limited nature of the documentation and inventories of these collections is already considerable.

The most famous case since the beginning of the unrest is the case of the Hama museum where, possibly among other artifacts, a golden Aramaic statuette was stolen. Interpol published a call for vigilance, and it has featured it on the most wanted list since December 2011.

Still in the Hama area, it has been reported that the Shaïzar citadel has also been looted.

At the Crac des Chevaliers, Bassam Jamous, General Director of the DGAM talks about armed groups penetrating the castle and starting illegal excavations. The same kind of illegal activities have also been witnessed in the provinces of Der’a,Hama and Homs.

PAS also addresses the possible pillaging of some pieces in the museum of Homs.

In Tartous, Mr. Marwan Hassan, Director of the Antiquities of the city mentions the confiscation of more than 1,300 objects (Classical and Islamic period) in an attempt to smuggle artifacts out of the country.

At Tell Hamukar in the Khabur Basin, some individuals witnessed what seemed to be an illegal excavation and episodes of looting. There is even a report of a house being built on the tell (PAS). Instances might also have been witnessed at Tell Ashari, Tell Afis, Khan Shiekhoun, and Tell Acharneh.

At the site of Afamya, in the city of Hama, some mosaics have been stolen.

At Palmyra, in addition to the presence of tanks in the area, there has been some evidence of looting and destruction in the Diocletian camp, and around the Bel temple. As of May 2015, ISIS forces have captured the ancient city of Palmyra.

At Apamée, one mosaic has disappeared as well as the chapiteau of the Decumanus column in the center of the city.

Finally, one needs to keep in mind the danger generated by the absence of authority and the unrest in areas surrounding several regional museums, including Ma’aret el-Nu’man, Ebla-Tell Mardikh, Qal’at Jabar, and Deir ez-Zor.

This category covers the damages done to Syria’s patrimony through military or civil occupation of archaeological areas and the shelling of monuments.

Multiple religious buildings have been damaged. The mosques of Der’a, Bosra and Inkhil, and the mosque al-Tawhid have suffered severe shellings. The minarets of Qa’ab el-Ahbar (Homs) and Al-Tekkiyeh (Ariha) as well as the Khaled Ibn al-Walid mosque at Homs have been partially destroyed. In Aleppo, the PAS points out damage done to the tomb of the Sheikh Dahur al-Muhammad and Mosque Abou Der Al-Gefary. Some Christian sites have also undergone some damage. These include the Deir Mar Mousa al-Habashi (The Monastery of Saint Moses the Abyssinian), Our Lady of Seydanya and Mar Elias monasteries, and the Umm el-Zinnar cathedral at Homs, where bullet impacts have been noticed. Even though the religious dimension of some of this destruction should not be overlooked, it is important to draw upon the fragmentation of our sources and the different reasons underlying the destruction of these monuments.

Military occupation also led to the destruction of several archaeological sites through shelling or the modification of landscapes. The monuments of Homs have been particularly damaged. In addition to the mosques previously mentioned, the dome of the Hammam al-Basha, Bab Dreb, the Suq al-Hashish, and possibly other parts of the Suq have been heavily damaged. In Hamma, the el-Arba’en quarter has been partly destroyed by fire. At Tell Sheikh Hamad, an Assyrian temple collapsed as the site was transformed into a battlefield. In the same way, the sites of Apamea (and its citadel), Palmyra, Bosra, Salamyeh-Chmemis castle, Ebla-Tell Mardikh, and Tell A’zzaz were heavily damaged when trenches and tank shelters were dug. An equal situation was witnessed at the Acheulean site of Latamne. Furthermore, in northern Syria, and especially in the region of Idlib, the area of the Limestone massif and its “dead cities” has also been the center of major destruction. So far, damages have also been reported in the villages of Kafr Nubbel, Ain Larose, Al-Bara, and Deir Sunbel.

The civil occupation of archaeological areas has additionally led to the progressive destruction of monuments, mostly through the reuse of archaeological material in the construction of new houses, but also through active degradation. The latter is exemplified by the case of the Roman temple of El Dumaier where graffiti has been found on the wall. The same issue has been witnessed at Bosra where some walls now carry traces of paint. In the province of Der’a, civil occupation of the area led to the reuse of blocks from sites such as Tell ‘Ashari, Tell Umm Hauran, Tafas, Da’al, Sahm el-Golan, and the ancient city of Matta’iya(PAS). Around Quneitra, the local government has allowed the construction of new buildings in protected patrimonial areas. This seems to also be the case at sites such as Tell’Ashara (Terka), Jabal Wastani, Sheikh Hamad, Sura, and Sheikh Hassan.

What is being done to protect Syria’s heritage?

The unrest in Syria has lasted for more than a year now. Quickly after the first protests, the first damage to Syria’s cultural heritage was witnessed: local people using ancient stones to build their houses, the military digging archaeological sites to protect their tanks, fights in Homs and Hama destroying the cities culture. It is still unclear in which context some of the damage is carried out. It is ultimately the responsibility of the Syrian government and the DGAM to protect its heritage against any kind of destruction. Several institutions have raised their concerns about the apparent disregard of the Syrian government to this destruction. Recent UNESCO talks in Bamako raised concerns about the situation in Syria and mentioned the possibility of sending a team of experts into sites such as the Krak des Chevaliers, Salah ed-Din Crusader castles, and Palmyra.

INTERPOL also sent a “call for vigilance on looting of ancient mosaics in Syria,” aiming to recover a number a mosaics stolen from Afamya. This, therefore, suggests that the international pressure in Syria is increasing and will hopefully soon lead to a concrete effort made towards the protection of the Syrian patrimony and the common cultural heritage of humanity.

Cultural heritage at risk: Cambodia

by SAFE (SAVING ANTIQUITIES FOR EVERYONE)

Cambodia contains within its modern borders innumerable archeological sites documenting more than 6,000 years of human habitation. Known sites cover the entire span of Southeast Asian history. They range from Paleolithic rock shelters, to open-air village sites that document the adoption of agriculture, bronze and iron metallurgy, to the formation of the earliest historic states which began to connect Cambodia to the world, and to the rise and fall of the Khmer empire that controlled much of mainland Southeast Asia from the 9th century to the early 15th century C.E.

This collective cultural heritage is seen as a source of national pride by most Khmer, especially when international collaborative projects can thoroughly excavate and document a site and share the findings with local communities and the world. In regards to the numerous examples of historic period monumental architecture that dot the countryside, those of the UNESCO World Heritage list such as Angkor Archaeological Park have become a great source of revenue thanks to mass tourism.

By the end of 2012, according to the Tourism Cambodia, Cambodia had received in excess of 3.5 million tourists, a figure that increased during each of the five years covered by the last MOU. Such tourism has proven to be a great source of economic revenue, but is also a primary factor fueling the looting of archeological sites to feed Cambodia’s continuing illicit antiquities trade.

What is at stake for Cambodia?

Many archeological sites, especially prehistoric cemeteries, remain undiscovered or improperly documented and thus vulnerable. Many smaller temple sites dating to the time of Angkor Wat’s construction (c. 12th century C.E.) and before also remain unexcavated, unmapped, and poorly known, although Cambodian governmental authorities such as APSARA, as well as established NGOs such as Centre for Khmer Studies, Heritage Watch, and the Memot Centre, have been doing their best to document and excavate or salvage as many sites as possible.

Despite these efforts, some historic period Khmer temple sites, especially smaller or more remote complexes (e.g. Preah Khan Kampong Svay, Koh Ker), have suffered recent looting or remain at risk. The ornate sculpture and statuary sites, such as these, are part of an art historical corpus that collectively covers every stylistic phase of the Khmer Empire as well as the precursor states of Funan and Chenla. Losing them to further looting and trafficking would do irreparable harm to future research.

Late prehistoric burial mounds (Iron Age, c. 500 BC-500 C.E.) are discovered underneath village houses and gardens and looted before they can be recorded (e.g. Prohear in Prey Veng Province, and Phum Snay and Phum Sophy in Banteay Meanchey and Badtambang Provinces). Even Bronze Age to early Iron Age (c. mid-1st millennium B.C.) “circular earthwork” sites, such as Memot and Krek 52/62 (in the “Red Earth” region of Kampong Cham province), have fallen prey to unplanned development.

Although multimedia awareness campaigns administrated by internationally collaborative NGOs and increasing action by Cambodian archeological, museum, and governmental authorities continues, it remains a race against time to discover and document archeological sites before looting occurs. The fundamental issue remains: how to balance the needs of local communities for stable, licit incomes (to which archeological tourism can contribute) with the need to preserve intact sites, excavate them when possible, and share new discoveries with diverse stakeholders.

For more information on what categories of artifacts are looted from Cambodia’s prehistoric and historic archeological sites, please consult the ICOM “Red List.”

The U.S. market demand for antiquities

Looting in Cambodia is fueled by the high demand for Asian antiquities on the global market. According to Sotheby’s website, 189 pieces of Cambodian origin have sold for more than $100,000 (U.S.) in the last few years. Some pieces can even fetch much higher prices. For example, during Sotheby’s 2012 March sale of Indian and Southeast Asian Art in New York, a statue of the goddess Uma, carved from polished brown sandstone and dating to the Baphuon period c. 11th century C.E. (lot 249), was sold for $530,000 (U.S.), while another Baphuon brown sandstone sculpture of Uma sold at Christie’s (lot 63) on September 23rd, 2004 for $1,127,500 (U.S.).

Legal and public relations battles between the Cambodian government and Sotheby’s auction house continue over the fate of a c. 10th century C.E. statue from remote Koh Ker. Many pieces present on the art market, especially prehistoric artifacts, do not have a clear provenience, first surfacing no earlier than the mid-1980’s. According to Davis (2011), approximately 80% of the 345 pieces of Cambodian origin that appeared at auction between 1988 and 1995 had no published provenience. Despite increasing scrutiny, auction houses both large and small tend to prefer “business as usual” if it is considered feasible or profitable.

What is Cambodia doing to protect its heritage?

Even though the Cambodian government has limited financial means to help protect its heritage, it is still making laudable efforts to safeguard major sites outside of the Angkorian complex. The APSARA authority and their international colleagues have been leading the effort to create a national database of all historic period monumental architecture sites, whether associated with Angkor or not. Furthermore, permission for all new archeological excavation or restoration projects must come from them.

Nevertheless, Cambodia has some legal means already in place that can help to stem the flow of antiquities when consistently applied. In 1996, Cambodia’s Law on the Protection of Cultural Heritage was enacted. This allows for a Cambodian artifact to be returned to the country if there is evidence proving that it was in Cambodia after 1996. Furthermore, Cambodia has ratified the 1970 UNESCO “Convention on the means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property” and the 1995 “Unidroit Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects.” These conventions provide the principal means through which signatory states can cooperate in an effort combat the illicit trade in antiquities and thus diminish the loss of cultural heritage globally.

For ten years Cambodia and the United States have held a bilateral Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) regarding cultural property. When fully enforced in both Cambodia and the U.S., it permits only those artifacts with a valid export license from the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts to enter the United States. The MOU also facilitates the prosecution of offenders and provides a strong legal foundation for repatriation claims involving U.S. public and private institutions.

Thankfully, the MOU with the United States was amended and extended for an additional five years, effective September 19, 2013; however, this does not mean Cambodia’s heritage is no longer at risk.

Cultural heritage at risk: United States

by SAFE (SAVING ANTIQUITIES FOR EVERYONE)

The United States experiences unique challenges with the looting of archaeological sites. Objects of cultural heritage, unless discovered on federal or tribal land, belong to the landowner. Federal lands are too vast to be closely monitored by the limited number of government officials. Therefore, the government’s successful prosecution of looters and prohibition of the black market is very challenging.

Ongoing collaborations between museum staff, the public, academia, and archaeologists have slowed the rate of looting. Still, sobering statistics indicate that it remains a substantial problem. Over 90% of known American Indian archaeological sites have already been destroyed or negatively affected by looters, and this process is ongoing. Further work is critical to prevent any more irreparable damage to our past.

What is at stake for the United States?

United States archaeological sites contain artifacts that are in some cases more than 14,000 years old. These sites tell a fascinating story of human history on the continent, from the origins of agriculture (Poverty Point, Louisiana) to Native American diversification, innovation, conflict, and European contact. Critical research on these topics is ongoing.

The Poverty Point site shows evidence of early experimentation with fired clay pottery. The Adena and Hopewell sites (Ohio River Valley, c. 1000 BCE–500 C.E.) are associated with elaborate grave goods and soft pottery. Cahokia Mounds (c. 800 C.E.) is a Mississippian center containing the largest pyramid built north of Mexico. Numerous burials found on this site reflect the complex social hierarchies and community structures that were in existence in those chiefdoms. In the southwest, most communities in early prehistory were small and widely scattered, with different styles of dwellings, ceramics, and subsistence practices revolving around the farming of corn, beans, squash, cotton, and other wild or semi-cultivated foods. Chaco Canyon (c. 900 CE) is a region in northwest New Mexico that contains several of the best examples of the “Puebloan” cliff-dwellings. Settlements here had populations rivaling those of today’s small towns.

Thanks to heightened public awareness and state and federal funding, large complexes such as Cahokia and Chaco Canyon are being preserved. However, such preservation efforts are limited to a small number of sites. Because most prehistoric and historic Native Americans lived in small, dispersed communities, looters take advantage of the small, remote sites if protective measures are not in place. Additionally, archaeological sites are frequently damaged to clear lands for agricultural or development projects.

By 1988, around 90% of known sites in the Four Corners (Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico) had been looted or vandalized. Most federal lands have not been surveyed (The National Park Service has surveyed only 10% of its 5.29 million acres). The small number of staff at most federal sites makes it difficult to devote a significant amount of time to patrolling and securing archaeological sites.

United States cultural heritage endangered

Looting and vandalism of archaeological sites has persisted throughout recent history. Between 1980 and 1987, for example, the Navajo Reservation saw a dramatic increase in vandalism and looting of archaeological materials. Between 1996 and 2005, there was an annual average of 791 incidents reported, but on annual average only 111 were solved or had the perpetrators prosecuted. Many Native American archaeological and ethnographic objects are sold in Europe, Japan, and Saudi Arabia through auctions that force Native Americans to participate in bidding to buy back their own cultural heritage.

Vandalism of rock art is also a growing concern. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is searching for the culprits that vandalized ancient Native American rock art located in the desert on the west side of Utah Lake.

Civil War era materials are also being illegally excavated. Bottle diggers scour outhouses of old frontier towns, and, in some extreme cases, people have robbed Civil War soldiers’ graves to steal human remains.

Market demand for U.S. antiquities

Native American artifacts, as well as contemporary artworks made by Native Americans, have been receiving more attention in the art and cultural property world. For example, the Santa Fe Indian Market has been growing in size and reputation; major museums like the Peabody Essex Museum and MFA Boston mounted Native American Art exhibitions or renovated galleries; Sotheby’s May 21 Arts of the American West auction fetched a total of $2,963,943; and Christie’s 2011 Native American Art auction reached a total sales volume of $1,116,187.

The international market has also turned its eye to Native American objects. In 2013, for example, French auction house Néret-Minet Tessier & Sarrou sold seventy artifacts for €930,000. Another known market price for Native American objects comes from the case of Pierre Servan-Schreiber, the Hopi tribe’s French lawyer, who bought a Hopi item for €13,000 from the EVE auctioneers in France with the intention of returning it to the tribe. The Annenberg Foundation also purchased twenty-four Native American objects for $530,000.

Yet an increase in market demand also means a potential increase in the sales of suspiciously acquired artifacts. For example, in November 2013, Skinner auction house pulled a Lakota object called “Sioux Beaded and Quilled hide Shirt” right before the auction started because the object might have belonged to a Lakota leader named Little Thunder. His descendants in the Rosebud reservation in South Dakota questioned the legitimacy of its ownership. The shirt was estimated to sell for $150,000-250,000.

What is the U.S. doing to protect its cultural heritage?

Some scholars comment that the U.S. Congress has been reluctant to enact broad-based cultural property protection measures. Numerous federal legislations, however, do exist with regards to specific problems. (See Kaufman, R.S. Art Law Handbook. Gaithersburg: Aspen Law & Business, 2000, especially p. 394-395).

The Antiquities Act of 1906 (16 U.S.C. §§ 431-33m) authorizes the penalization of anyone who destroys or damages historic ruins on public lands, or excavates ruins, monuments, or antiquities on lands owned or controlled by the federal government. This was later supplemented by the Archaeological Resources and Protection Act of 1979 (16 U.S.C. §§ 470aa-mm), which specifically protects archaeological resources on public or Indian land from sale, exchange, or transport without proper permission.

The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (42 U.S.C. § 4321-70a) requires the government to use “all practicable means and measures” to preserve important historical and cultural sites.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1991 (NAGPRA) (25 U.S.C. §§ 3001-3013) further addresses specific Native American cultural property concerns. NAGPRA required museums receiving federal funds and other federal institutions to inventory any American Indian human remains, funerary objects, or sacred items. Descendants or related tribes hold the right to decide whether items should be returned to the tribe, reburied, or held in the collections long-term. Under NAGPRA, anyone who is found guilty of illegal trafficking of these items can be sentenced with judicial penalties. This legislation has helped to discourage the removal of objects and human remains.

Most significantly, in 1983, the U.S. signed into law the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA). This is an implementation of the 1970 UNESCO Convention in the context of the United States and its cultural property importation policies. Under this legislation, the U.S. can enter bilateral or multilateral agreements with other State Parties to the 1970 UNESCO Convention, or impose emergency import restrictions, provided that a State Party requests it.

The National Stolen Property Act (NSPA) has been relevant to the import restriction of suspicious items and criminal punishment of illegal importers. It provides that “[w]hosoever transports, transmits, or transfers in interstate or foreign commerce any goods, wares, merchandise . . . of the value of $5,000 ore more, knowing the same to have been stolen, converted or taken by fraud . . . shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years or both.”

The National Historic Preservation Act (16 U.S.C. §§ 470a to 470w-6) is one of the most systematic programs of historic preservation. It established various Historic Preservation Offices, which create inventories of archaeological and historic properties.

Some states, like Arkansas, have created their own programs to spread awareness of the issues to the general public. As of 2013, over 700 citizens belonged to the Arkansas archaeological Society, each having participated in the Arkansas Archaeological Survey Training Program in which members of the public learn excavation techniques and ethical issues in American archaeology. Other state branches of the National Park Service, such as the one in South Dakota, have implemented awareness and stewardship programs and telephone hotlines in an attempt to enlist citizens as site stewards.

Federal and state laws and programs are taking steps in the right direction toward public awareness and criminal prosecution of looters, but more work is needed to continue to document and protect what remains.

Other efforts to protect the United States’ cultural heritage

The National Park Service provides information and education on looting prevention and historic site preservation. Its archaeology Program page is a goldmine of resources. It also runs the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT), which advances the application of science and technology to historic preservation in the fields of archaeology, architecture, landscape architecture, and materials conservation.

SAFE has been working on promoting public awareness on the dangers of archaeological looting in the United States. Various blog posts by archaeologists provide insights into the current state of looting in the United States.

The Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) has implemented a Site Preservation Program, which focuses on grant giving, recognition, and public outreach. It has also been involved in shaping a better understanding of archaeological ethics among the public by, for example, speaking out against treasure hunting TV shows that might promote looting and destruction of archaeological sites.

Other professional archaeological organizations include the Society for American Archaeology (SAA), which promotes archaeological ethics and participates in CPAC testimonies, and the Society for Historical Archaeology (SHA), which promotes scholarly research and the dissemination of knowledge concerning historical archaeology.

United States’ response to international cultural heritage problems

The United States has historically favored free imports of cultural property, acknowledging that exchanges enhance knowledge of the civilizations and enrich the cultural lives of all people. But import restrictions are sometimes legislated under certain political embargoes or limit the trade on stolen works of cultural property.

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) assists the U.S. and foreign governments in evaluating foreign countries’ requests for bilateral agreements to establish import restrictions. CPAC consists of eleven members, who include individuals from the fields of archaeology, anthropology, ethnology, and museums.

A number of federal agencies contribute to the enforcement of the treaties, laws, and restrictions regarding cultural heritage, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)’s Art Crime Team, which coordinates with international law enforcement agencies like INTERPOL. See a more detailed discussion here.

In addition, the United States enters into bilateral agreements with several nations to prevent the importation of those nations’ cultural heritage—a further explanation about which can be read here.

Saving Venice

by LISA ACKERMAN and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): A conversation about the issues facing Venice and efforts to save the historic city, with Lisa Ackerman, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, World Monuments Fund and Steven Zucker

Additional resources:

Venice (from the World Monuments Fund)

Marcello Rossi, “Will a Huge New Flood Barrier Save Venice?” Wired Magazine, April 5, 2018

As Tourists Crowd Out Locals, Venice Faces ‘Endangered’ List (from NPR)

Robert C. Davis, Garry R. Marvin, Venice, the Tourist Maze: A Cultural Critique of the World’s Most Touristed City (University of California Press, 2004)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The unintended consequences of UNESCO world heritage listing

by CHLOÉ MAUREL

Chloé Maurel, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS)

The principle of world heritage promoted by UNESCO is of crucial importance at a time when tourism has become a global phenomenon, involving more than a billion people and generating an annual revenue of nearly US$1245 billion in 2014.

With the 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, UNESCO created the list of sites thought to be of exceptional value. While listing does not automatically lead to funding for the protection of listed sites, and although UNESCO is powerless to stop them being destroyed or damaged (like the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001, or the Temple of Baal in Palmyra, Syria, demolished in 2015), the list of world heritage sites remains a key element of UNESCO’s work, and what it is best known for by the general public.

UNESCO world heritage listing confers prestige. It is sought after by countries wishing to promote their historical and natural assets, and gives them a place on the world stage.

Tangible, intangible and documentary heritage

The list of world heritage sites now comprises more than 1,000 sites. Another, the intangible cultural heritage list, was created in 2003 to catalogue practices, traditions, dances, customs and know-how, rather than physical sites. In part, its purpose is to redress the obvious asymmetry in the first list, which contains an overwhelming majority of European sites, while Africa is drastically underrepresented. Moreover, listed sites in Africa are mostly “natural” heritage sites, while Europe has a surfeit of “cultural” sites, such a churches and castles, that are already highly valued and do not necessarily require further protection.

In 1995, UNESCO also created a register called The Memory of the World, listing significant and sometimes endangered or fragile artefacts of human documentary heritage, such as the Bayeux tapestry.

It would be easy to assume that these initiatives unite people in a common effort to protect shared cultural heritage. In fact, they often spark power struggles and rivalries, or even open conflict, demonstrating that the principle of heritage can be appropriated for financial, political or geopolitical ends.

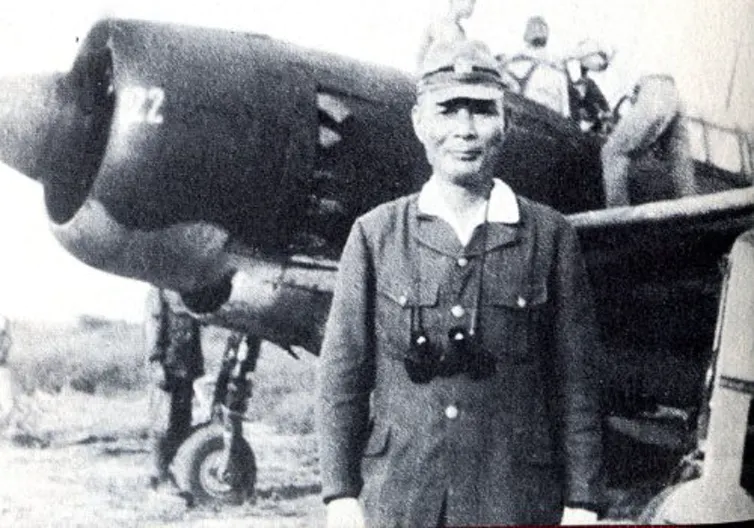

The most striking example is the conflict between Japan and China following Japan’s recent request to have 333 letters from second world war kamikaze pilots included in The Memory of the Word registry. These goodbye letters, written by pilots to their families before their final attack, often reflect their pride in fighting for what was then a racist and imperialist regime, allied with Nazi Germany.

China objected and in turn asked for, and was granted, the inclusion of a set of documents pertaining to the 1937 Nanjing massacre, carried out by Japanese forces, which reportedly claimed 300,000 Chinese lives. This is a clear example of the listing being used as an extension of hostile relations between China and Japan, whose memories of the second world war are still a sensitive subject.

Mass tourism at listed sites

Several cases illustrate the problematic nature of UNESCO’s heritage protection measures. Very often, the principle of world cultural heritage is diverted from its official purpose and used to promote tourism, or for political and economic reasons. In his study of UNESCO’s heritage policies, anthropologist David Berliner speaks of the “Unescoization” of the small heritage listed city of Luang Prabang in Laos. He demonstrates that one of the contradictory consequences of UNESCO protection is intense tourism development.The development of tourism has idealised traditions, which are being staged, sometimes inaccurately in Luang Prabang. Historical events, such as those of the Vietnam War and the colonial era are completely neglected.

Heritage listing can also have adverse consequences, as has often been the case in Africa. Saskia Cousin and Jean-Luc Martineau studied how customs and traditions can be exploited following their appearance on the list of world heritage sites. In their study of Nigeria’s “Sacred Grove” in Osun-Osogbo, they demonstrated that lobbying, combined with political and economic interests, played a central role in its 2005 listing.

In this particular instance, it was politically desirable to attribute historical depth to the new capital of the state of Osun, in order to compete with the rich past of its rival city, Ife.

The inclusion of the Sacred Grove of Osun-Osogbo on the World Heritage list is the result of nearly 15 years of efforts on the part of Osun state to give itself cultural and historical legitimacy.

Negative outcomes for local populations

Prestigious as it is, the list of world heritage sites can also negatively affect sections of the local population. In Panama City, the 1997 listing of the historic Casco Viejo neighbourhood relegated its poorest inhabitants to the city limits. Meanwhile, the central district became a tourist attraction.

At the time, the Casco Viejo was a run-down neighbourhood. It underwent a radical transformation, resulting in the brutal eviction of people from the poorer classes, whose windows were boarded in attempts to force them out while the surrounding neighbourhood was restored and gentrified.

It is now largely inhabited by rich foreigners who buy up the best colonial buildings to sell off in parcels. Tourism in Panama City has increased exponentially since the heritage listing, homogenising the urban landscape and exacerbating inequalities.

These examples show how issues of heritage are closely linked to economic, social and political issues, and result in power disparities. Given the disproportionate role of officials and experts from Western countries in UNESCO’s heritage work, the organisation could be accused of imposing a Western vision of heritage on countries in the Global South.

In spite of these imperfections, we should commend UNESCO on its efforts to preserve our world heritage. But the visible imbalance in the list of sites simply reflects the economic, social and cultural inequalities of the North-South divide. These must urgently be addressed.

Translated from the French by Alice Heathwood for Fast for Word.

by Chloé Maurel (CC BY-ND 4.0)

This article was originally published on The Conversation.