12.8: The role of archaeology

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147875

What is archaeology: understanding the archaeological record

by DR. JEFFREY A. BECKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Speakers: Dr. Jeffrey Becker and Dr. Beth Harris

Additional resources:

Archaeological Institute of America

Neil Brodie and Kathryn Walker Tubb, Illicit Antiquities: The Theft of Culture and the Extinction of Archaeology (Routledge, 2011)

N. Brodie, M.M. Kersel, C. Luke, and K.W. Tubb, eds., Archaeology, Cultural Heritage, and the Antiquities Trade (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006)

Eric Cline, Three Stones Make a Wall: The Story of Archaeology (Princeton University Press, 2017)

Saved by shipwreck, The Antikythera Youth

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Saved by shipwreck, The Antikythera Youth," in Smarthistory, July 19, 2020, accessed September 14, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/antikythera-arches/.

The rediscovery of Pompeii and the other cities of Vesuvius

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E. destroyed and largely buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and other sites in southern Italy under ash and rock. The rediscovery of these sites in the modern era is as fascinating as the cities themselves and provides a window onto the history of both art history and archaeology.

Pompeii today

Today the site of Pompeii is open to tourists from all over the world. Major projects in survey, excavation, and preservation are supervised by Italian and American universities as well as ones from Britain, Sweden, and Japan. Currently, the major concern at Pompeii is conservation—officials must deal with the intersection of increased tourism, the deterioration of buildings to a sometimes dangerous state, and shrinking funding for archaeological and art historical monuments. The 250-year-long story of the unearthing of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the other sites destroyed by Vesuvius in 79 C.E. has always been one of shifting priorities and methodologies, yet always in recognition of the special status of this archaeological zone.

Hidden for centuries?

The popular understanding of the immediate aftermath of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius is that Pompeii, Herculaneum, and sites like Oplontis and Stabiae, lay buried under ash and volcanic material—completely sealed off from human intervention, undisturbed and hidden for centuries. Archaeological and geological evidence, however, indicates that there were rescue operations soon after the eruption (see, for example, the tunnels dug through the House of the Menander) and that some parts of these cities remained visible for some time (the forum colonnade at Pompeii was not completely covered). Throughout the Middle Ages, Pompeii was entirely deserted, yet locals referred to the area as La Cività (“the settlement”), perhaps informed by folk memory of the city’s existence.

Excavations begin

While Renaissance scholars must have been aware of Pompeii and its destruction through various ancient written sources, the first “archaeologist” in the area was apparently unimpressed with his discoveries. From 1594-1600, the architect Domenico Fontana worked on new constructions in the area and accidentally excavated a number of wall paintings, inscriptions, and architectural blocks while digging a canal. No one undertook follow-up explorations for nearly a century and a half, despite the general interest in antiquity and rudimentary archaeology at the time.

The eighteenth century saw the first large-scale excavations in this region, motivated by the desire to collect works of ancient art as much as by a scientific curiosity about the past. Further incidental discoveries in the early decades of the 1700s prompted Charles VII, King of Spain, Naples, and Sicily, to commission a survey of the area of Herculaneum.

Official excavation began in October 1738, under the supervision of Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre, a military engineer who tunneled through the practically petrified volcanic material to find remains of Herculaneum more than 20 meters under the surface. This dangerous work (tunnel collapse and toxic gases were a constant threat), yielded wall paintings, life-size sculpture in both bronze and marble, and papyrus scrolls from the Villa of the Papyri. Many of these recovered works went to decorate the palace of the king. Archaeology was still in its infancy as a practical field of study at this time, and was often more about “treasure-hunting” than careful research or documentation.

A Swiss engineer, Karl Jakob Weber, took over the excavation of Herculaneum from de Alcubierre in 1750 and brought more cautious methods to the site. Weber’s practices of recording the findspots of important objects in three dimensions and making detailed plans of architectural remains laid the foundations for the indispensable procedures of modern archaeology. De Alcubierre shifted his focus to Pompeii, which had just been (re)discovered in 1748. Among the early excavations there were the amphitheater and an inscription confirming the town’s name: REI PUBLICAE POMPEIANORUM. With finds from Herculaneum and Pompeii increasing exponentially, King Charles inaugurated a Royal Academy in Naples in 1755, dedicated to mapping the sites and publishing significant discoveries.

The new fields of archaeology and art history and the building of a royal collection

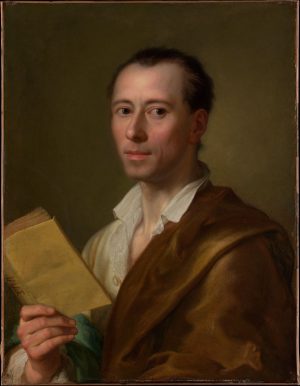

The field of art history was emerging concurrently with these early excavations and naturally sites like Pompeii and Herculaneum were of great interest to the man who coined the term “history of art”—the German scholar Johann Joachim Winckelmann. His reports on the finds from this area fanned the flames of European fervor for classical antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome), and Grand Tour travelers from Britain and elsewhere beat a path to Pompeii and Herculaneum in the late 18th century.

Although Winckelmann was most concerned with categorizing Greek and Roman sculpture, he was also keenly interested in the new field of archaeology: he knew enough of this science to criticize the secrecy and aggressive methods of de Alcubierre, an action that got Winckelmann effectively banned from Pompeii.

It was actually King Charles’s desire (and that of his successor Ferdinand) for beautiful artifacts that closed much of the excavations off to outside scholars, with most of the important finds going directly into the private royal collection. The king also enacted laws forbidding the export of antiquities from the Kingdom of Naples. Even the publication of the monumental Le antichità di Ercolano esposte (The antiquities of Herculaneum displayed, 1757-92) was tightly controlled and the illustrated volumes were only selectively presented to other European monarchs by the king himself.

Preservation and access

With the arrival of Francesco la Vega as director of excavations in Pompeii in 1780, the conservation of buildings and artifacts became a priority. Francesco, and his brother Pietro after him, removed valuable artifacts to the new Naples Museum, where they joined other pieces from the royal collection. Francesco la Vega also embraced Weber’s concerns for recording three-dimensional contexts, and it was under his leadership that the Triangular Forum, the Temple of Isis, and the theater district were uncovered. However, like many archaeologists at Pompeii, la Vega struggled with a significant conflict: a desire to preserve the rare ancient wall paintings in situ while maintaining the site as a singular opportunity for visiting an ancient Roman city whose walls and roofs still stood. Paintings and buildings were left open to both treasure-hungry visitors and the elements, resulting in both natural and man-made deterioration at Pompeii.

Perhaps no archaeologist had such a significant influence on the exploration of Pompeii as Giuseppe Fiorelli. He was superintendent of Pompeii for twelve years (1863-1875) during a supremely patriotic moment after the unification of Italy in 1860 when the country’s archaeological heritage was a tremendous source of pride. Fiorelli did not meet his goal of uncovering the entire city—only about one third of the Pompeii was excavated—but he accomplished other important tasks and brought new techniques to the site.

Opening the site to visitors and the first entrance fee

Fiorelli systematically organized the site by dividing it into nine regions and providing a system of “addresses” for insulae (city blocks) and doorways. In a dramatic shift from the restrictive 18th-century approach to tourism in Pompeii, Fiorelli opened the site up to visitors from all over the world—and he also introduced the first entrance fee. His exhaustive reports on the excavations kept scholars apprised of developments on the site.

Fiorelli is best known for his use of plaster casting techniques which permitted a kind of preservation of otherwise ephemeral archaeological finds like wood and human remains. By pouring plaster into voids in the ash left by decomposed organic material, Fiorelli’s casts gave form to things like wooden doors, window frames, furniture, and of course the victims of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The casts of human remains—including adults and children, not to mention a pet dog—remind visitors to this day that the great gift of Pompeii’s archaeology came at tremendous cost (as many as 2,000 people lost their lives).

Archaeological investigation continues—as an international project

In the late 19th century, exploration of Pompeii and Herculaneum became a more international project. The British diplomat Sir William Hamilton had already published studies of volcanic activity and painted pottery from the region in the late 18th century. German scholars of the 1800s studied inscriptions (Theodor Mommsen), outlined the city plan (Heinrich Nissen), and created typologies of wall painting (Wolfgang Helbig). August Mau’s thorough categorization of the Four Styles of Pompeian frescoes, published in 1882, remains the basis for wall painting studies today. The late 19th century also saw the excavation and restoration of two of Pompeii’s most spectacular houses—the House of the Vettii and the House of the Silver Wedding.

Pompeii in the 20th century: interruptions to archaeological work and bombing

The 20th century continued to be a very productive time at Pompeii for Italian archaeologists, even though work was interrupted by world events. Vittorio Spinazzola (director, 1911-1923) opened a massive excavation campaign along the Via dell’Abbondanza. His work not only uncovered important residences like the House of Octavius Quartio, but also contributed to our understanding of upper floors of Pompeian buildings. Spinazzola’s work was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I and he was forced to step down from his position by Italy’s Fascist government. Amedeo Maiuri was the director of excavations from 1923-1962 and oversaw the discovery of the Villa of Mysteries and the House of the Menander.

Although work was stopped again at Pompeii during the Second World War, Maiuri succeeded in broadening the excavations to the extent seen today: about two-thirds to three-quarters of the city’s final phase has been uncovered. Maiuri was also concerned with pre-Roman Pompeii, opening excavations below the most recent layer; he also undertook extensive restoration and conservation work.

A terrible moment for Pompeii occurred in 1943 when the Allies dropped more than 150 bombs on the site, believing Germans were hiding soldiers and munitions among the ruins. At least one bomb fell on the on-site museum, destroying some of the more interesting artifacts discovered by that time.

Nevertheless, thanks to the efforts of the many archaeologists and researchers who have worked to uncover the remains of Pompeii and Herculaneum over the last three centuries, today we can again walk the streets of these fascinating ancient Roman towns.

Additional resources:

The eruption story from The British Museum

Dr. Damian Robinson, “The Elite House and Commercial Life along the Via dell’Abbondanza”

Dr. John J. Dobbins, “Public Space and via dell’Abbondanza”

Archaeological Areas of Pompei, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata (UNESCO)

The importance of the archaeological findspot: The Lullingstone Busts

by DR. ELIZABETH MARLOWE and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

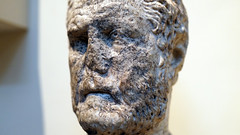

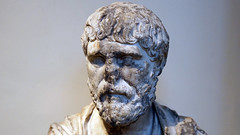

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Two marble portrait busts, 2nd century C.E., found during an excavation in 1949, Lullingstone Roman Villa, Kent (British Museum, on loan from Kent County Council). Speakers: Dr. Elizabeth Marlowe and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources:

Lullingstone Roman Villa (from English Heritage)

G. W. Meates, The Lullingstone Roman Villa, Archaeologia Cantiana, vol. 63 (1950), pp. 1-49.

K. S. Painter, The Lullingstone Wall-Plaster: An Aspect of Christianity in Roman Britain, The British Museum Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 3/4 (Spring, 1969), pp. 131-150.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

When there is no archaeological record: Portrait Bust of a Flavian Woman (Fonseca bust)

by DR. ELIZABETH MARLOWE and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Portrait Bust of a Flavian Woman (Fonseca bust), early 2nd century C.E., marble, 63 inches high (Capitoline Museum, Rome). Part 1 can be watched here.

Additional resources:

Elizabeth Marlowe, Shaky Ground: Context, Connoisseurship and the History of Roman Art (Bloomsbury Academic, 2013)

Conservation vs. restoration: the Palace at Knossos (Crete)

Restoration versus conservation

What happens to an archaeological site after the archaeologist’s work is completed? Should the site (or parts of it) be restored to what we believe (based on evidence) it once looked like? Or should the site be protected through conservation and left as is? A visit to an unrestored archaeological site can be uninspiring—even the most lavish ancient sites can appear to be piles of unorganized stones framed by broken columns and other fragments. And while modern conservation principles insist on the reversibility of any treatment (in case better treatments are discovered in the future), in the past, conservators didn’t have the resources or science that is available today.

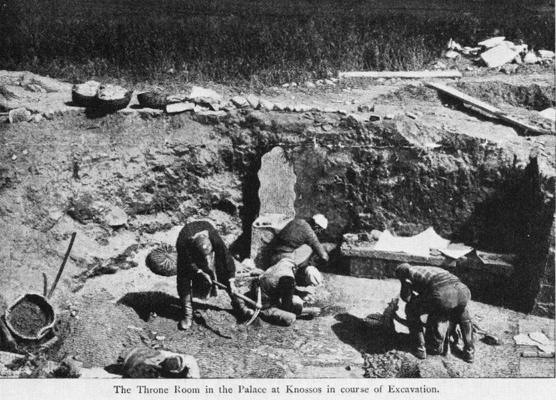

Knossos

The archaeological site of Knossos (on the island of Crete) —traditionally called a palace—is the second most popular tourist attraction in all of Greece (after the Acropolis in Athens), hosting hundreds of thousands of tourists a year. But its primary attraction is not so much the authentic Bronze Age remains (which are more than three thousand years old) but rather the extensive early 20th century restorations installed by the site’s excavator, Sir Arthur Evans, in the early twentieth century.

Archaeological restorations offer important information about the history of a site and Knossos doesn’t disappoint—one can see the earliest throne room in Europe, walk through the monumental Northern entrance to the palace, marvel at colorful wall paintings and enjoy the elegance of a queen’s apartments. All these spaces, however, are the result of extensive, contentious and, in some cases, damaging restoration. Knossos asks us to consider how we can preserve an archaeological site, while at the same time providing a valuable, educational experience for visitors that nonetheless remains true to the remains.

Considering Evans’ reconstructions

The Evans restoration at Knossos are important for several reasons:

- If Evans hadn’t worked to preserve and restore so much of Knossos beginning in 1901, it would have undoubtedly been largely lost.

- The restoration of the site undertaken by Evans, with its elegantly painted Throne Room (below) makes very real our historical understanding, originally revealed by Homer, of the power and prestige of the kings of Crete.

- The beautiful, although sometimes inaccurate, restorations of architecture and wall paintings by Evans evoke the elegance and skill of Minoan architects and painters.

These are the undeniable benefits of Evans’s restorations and among the aspects of a visit to Knossos that everyone values. It is the smooth corniced walls, bright paintings, and whole passages stepped with balustrades at Knossos that the post cards, camera snaps, and human memory preserve, and that has translated into important support for the site—intellectually, politically, and financially.

At the same time, the Evans restorations are problematic. In some cases, what is restored does not accurately reflect what was found. Instead, a grander, and more complete, experience is presented. For example, when you visit Knossos, because of the way it is reconstructed, it is very easy to believe that all that was ever found there was a Late Bronze Age palace.

Evans’s restoration of the Throne Room (and much else at the site) privileges the Late Bronze Age period of its history. The typical visitor likely won’t grasp that the Throne Room dates to the latest phase of Knossos—the end of the 2nd millennium B.C.E., though the site was occupied nearly continuously from the Neolithic to the Roman era (from the 8th millennium B.C.E. to at least the 5th century C.E.).

The power of Evans’s interpretation and reconstruction of the site as purely Minoan—the product of the indigenous culture of that island—is very much still with us despite the fact that much has changed about how art historians and archaeologists understand the different periods of construction at Knossos. Today, much of its final plan and form, which Evans reconstructed (including the Throne Room and most of the frescos), are understood as being of Mycenaean construction (not Minoan). Although this information is noted in texts mounted at the site, it is too often overlooked by visitors.

What is archaeological restoration?

When archaeological remains are revealed through excavation, they are often delicate and cannot survive long unprotected. Some archaeologists backfill their trenches (refill the excavated holes with the material that was removed) to help preserve remains. In other instances, architecture, graves, or the impressions left from ephemeral building materials (such as wood) are sometimes left exposed, and when this happens some sort of conservation should occur. By definition, any sort of conservation is restoration when the modern materials are layered on the ancient and made to look harmonious in form, color and/or texture. As a result, restorations are sometimes nearly indistinguishable from authentic materials, and this is where things get tricky—such as the situation at Knossos.

Before making an archaeological restoration, three essential issues must be examined:

- What specific point in a site or monument’s history will be the subject of the restoration? Many (most!) archaeological sites reflect a long occupation or use, and within that timeframe things change, are repaired, or rebuilt. What era of the site will be privileged by the restoration—and in turn, which eras of the site’s history will become harder to see and understand?

- How will future changes in the interpretation and knowledge about a site or monument be accommodated by restorations? Archaeological interpretations of sites evolve all the time, often through new discoveries elsewhere. Restorations, in order to remain accurate, need to take into account potential new scholarship that can change the history or meaning of a site or monument.

- Lastly and most importantly, restorations must be non-destructive and reversible. The first role of restoration is conservation. Therefore, the original remains must be entirely safe and not harmed in any way by restoration methods and materials. The reversibility of restorations not only has to do with the accommodation of changes in interpretation made above, but also with the need to leave the way open for less invasive, more gentle restoration methods in the future.

Restoration at Knossos

Aside from some gaps (for instance, during the First World War) Evans excavated at the site of Knossos each year from 1900 to 1930. Restoration of the architectural finds began almost immediately and can be divided into three phases, each characterized by the architect Evans hired to do the work. These three men, Theodore Fyfe, Christian Doll, and Piet De Jong, each had very different restoration philosophies.

Phase 1: Theodore Fyfe

From 1901 to 1904, a young architect by the name of Theodore Fyfe was charged with the restorations at Knossos. It is likely that Evans hired him because the winter of 1900/01 had damaged the newly exposed Throne Room—the most important space excavated during that first season at the site.

Fyfe’s work at Knossos can be characterized by two things. First of all, he was devoted to the concept of minimal intervention. Second, when intervention was necessary, he made great efforts to use materials authentic to the Bronze Age structure (wood, limestone, rubble masonry) and even to use Bronze Age construction techniques, which he was able to glean from his onsite work. Clearly Fyfe was highly concerned about the truthfulness of his interventions and reconstructions; the only exception to this was his construction of modern-style pitched roofs to protect the Throne Room and the Shrine of the Double Axes.

Phase 2: Christian Doll

The second phase of restoration work at Knossos dates from 1905 to 1910, and was directed by Christian Doll. The first conservation work to which Doll had to attend to in 1905 was that of Fyfe’s. Essentially, Fyfe’s zeal to use authentic materials resulted in failure: he neglected in many cases to treat timbers before their use and he tended to use softwoods rather than hardwoods (all of which lead to rot). Also, rain was a destructive force in the winters, especially when it ran through newly exposed parts of the site. Doll’s first and most important project was to stabilize and reconstruct the Grand Staircase to its original four story height. This was an extremely difficult job as the exact nature of the ancient design eluded both him and Fyfe, so a certain amount of improvisation was needed. And, because the weight of the structure was so great, Doll used iron girders (imported from England at great expense) covered in cement to make them look like ancient wooden beams.

Doll’s approach to conservation was still anchored in preserving the excavated remains. However, Doll was no fan of the authentic materials used by Fyfe, as he saw how they had failed to preserve the many areas where they had been employed. Instead, Doll constructed structural systems based on techniques used in London at the time. Moreover, he employed contemporary architectural materials, such as the iron girders mentioned above, as well as concrete (the first use of this material at Knossos).

Phase 3: Piet De Jong

The third phase of conservation work was executed over a longer period of time, from 1922 to 1952, by Piet De Jong. The vast majority of what Knossos looks like today, with large passages of reconstructed walls and rooms, is his work.

Three main elements characterize De Jong’s work at Knossos. The most prominent was his use of iron reinforced concrete. In the twelve years between Doll’s and De Jong’s work, the use of reinforced concrete had grown in popularity because of its speedy construction, its relative cheapness, and its ability to be molded into nearly any shape. It was also thought to be nearly indestructible.

Another essential characteristic of De Jong’s work at Knossos was his use of reinforced concrete to construct parts of the palace beyond what had been found—some passages were based on archaeological evidence, some were not (the bases of these reconstructions came from Evans himself).

De Jong often did not merely end walls at the height of their discovery but would either finish them off with a flat roof and cornice, often decorated with double white horns (what some contemporary wall paintings of Bronze Age houses looked like), or would leave the top edge of walls with irregular stones, evoking a picturesque, antique view. When a complete vision of ancient Knossos could not be reconstituted, a romantic one was built instead.

The reconstruction of the interior decoration of the throne room was executed during this period and similarly exhibits a combination of the truthful reflection of archaeological remains and Evans’s creativity.

Lastly, an important characteristic of De Jong’s restorations was the placement of reproductions of wall paintings around his newly built spaces. Some paintings were placed very close to their findspots and therefore aimed at a more authentic reconstruction, while other paintings were reconstructed at some distance from where they had been discovered.

The question remains: why did Evans encourage De Jong’s radical approach to conservation, especially after two more conservative predecessors? Several reasons are at play, no doubt. The first, and possibly the most important, is the condition of Knossos after almost eight years of abandonment during the First World War. Aside from the wild overgrowth of weeds, there was much weather-related and other damage. However, the parts of the site that had been roofed (such as the Throne Room and the Shrine of the Double Axes) and sections that were more intact (such as the Grand Staircase), were in excellent shape and this no doubt convinced Evans of the importance of aggressive conservation work. Second, the iron-reinforced concrete which De Jong proposed to use was inexpensive and could be employed quickly. Third, Evans, in a masterful anticipation of the desires of future tourism, aimed to make a site that would vividly conjure the culture he had discovered, as much evocative and picturesque as historically accurate.

Conservation at Knossos after Evans

It is only fair to reflect upon the restorations of Knossos within their historical framework. The aims, methods, and materials used in restoration at the site over a period of some sixty years changed, reflecting a long list of crises, constraints, theories, and desires. Perhaps most significant, however, was Evans’s overriding conviction that the conservation of Knossos was an obligation born out of its great antiquity and unique importance. He knew this from his own Edwardian education, British colonial outlook, and his twenty-four year directorship of the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford. Evans was keenly aware of how intimately connected the teaching of Knossos’s history was with how it was presented on site. He made Knossos into a museum and a showcase for the newly discovered Aegean Bronze Age chapter of ancient history and the earliest example of cultural tourism, today a mainstay of public historical education—not to mention local economies. Evans did it first at Knossos.

Conservation at Knossos has continued since De Jong’s work, although with new challenges. The most recent conservation work on the site has been focused largely on repairing Evans’s reconstructions. Despite a belief that reinforced concrete would last indefinitely, it has proven to be susceptible to the wet Cretan winters, crumbling and allowing for rust on the interior ironwork. In other areas the reinforced concrete proved to be structurally unsound.

In addition, the steady increase of tourist traffic since the 1950s has meant growing stress on both the original architecture of Knossos as well as its reconstructions. Sustained foot fall, increasing weight load as well as touching and sitting, is increasingly destructive. To combat this, the Greek Archaeological Service, under the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, has closed off large sections of Knossos and generally restricted circulation on the site. In the 1990s it conducted extensive conservation of both ancient and modern structures as well as building new corrugated plastic roofing. At present the Service is working on a visitor management plan for the site and the Greek government has applied to UNESCO for World Heritage Status for Knossos as well as four other Minoan palatial sites which would afford much needed support for ongoing conservation efforts.