12.7: Documenting and protecting cultural heritage

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147874

Diarna: documenting the places of a vanishing Jewish history

by JASON GUBERMAN-PFEFFER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): A conversation with Jason Guberman-Pfeffer, Executive Director, Digital Heritage Mapping, Inc. and Coordinator, Diarna Geo-Museum and Beth Harris.

A Landmark Decision: Penn Station, Grand Central, and the architectural heritage of NYC

by DR. MATTHEW A. POSTAL and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Dr. Matthew A. Postal and Dr. Steven Zucker discuss landmarks preservation in New York City while visiting: Charles Luckman Associates’s Madison Square Garden and Pennsylvania Station, the former site of Charles McKim for McKim Mead, & White, Pennsylvania Station (New York City), 1910 and then visiting Reed & Stem, Warren & Wetmore’s Grand Central Terminal, 1912

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Frameworks for cultural heritage protection: from ancient writing to modern law

Major threats to cultural heritage come in two forms: destruction during military conflict and the looting of sites and collections. Both in antiquity and in contemporary times, we see these destructive activities often going hand in hand, but we also see a consistent development toward recognition that such cultural remains should be protected.

Toward a recognition that cultural heritage should be protected

In the second century B.C.E., the ancient Roman author Polybius criticized the Roman plunder of Greek sanctuaries on Sicily. A century later, the Roman orator, Cicero, prosecuted the Roman governor of Sicily, Gaius Verres, for excessive looting of Sicilian cities. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius and the international legal theorist Emmerich de Vattel established principles stating that, as works of art were not useful to the military effort, they should be protected.

During the Napoleonic Wars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the French looted artworks from throughout Europe as well as from Egypt and brought them to Paris, which was to be recreated as the “new Rome.” With the defeat of Napoleon, the British leaders (the Duke of Wellington and Viscount Castlereagh) not only declined to take these collections for Britain but decreed that the French should return those artworks taken from other European nations. Despite this, only about half of the works looted by Napoleon—and none of those taken from non-Europeans—were returned.

During this same time period, the British Lord Elgin, at that time ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, removed sculptures and architectural elements from the Parthenon and other structures in Athens and brought them to London, where they were later purchased by the British Museum.

The Lieber Code

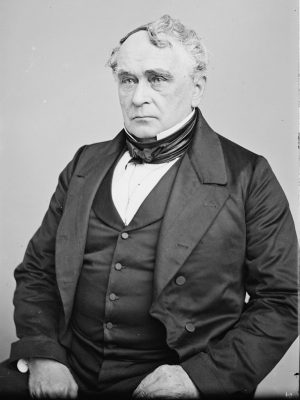

In 1863, during the American Civil War, the first military code of conduct was written at the request of President Abraham Lincoln by Francis Lieber, who had been present as a young soldier at the Battle of Waterloo. Lieber later studied the classics and then moved to the United States, where he became a professor of history. Known as the Lieber Code, it addressed the same two threats discussed above: destruction and looting. Lieber wrote that structures devoted to religion or education and museums of the fine arts and science should not be destroyed during armed conflict and “classical works of art, libraries, scientific collections or precious instruments…must be secured against all avoidable injury even when they are contained in fortified places whilst besieged or bombarded.” He added that such objects shall not “be sold or given away…nor shall they ever be privately appropriated, or wantonly destroyed or injured.”

First international conventions

The Hague Conventions and Regulations of 1899 and 1907 were the first international instruments to codify rules on the conduct of warfare. Influenced by the Lieber Code, they ingrained these same concepts of protection into international law. These two Hague Conventions were the governing instruments during both World Wars. While these Conventions did not prevent large-scale theft and destruction of cultural objects and structures—particularly during the Second World War—they served as the basis for prosecution and punishment of those who violated their principles.

The Hague Convention after WWII

At the end of the Second World War, in response to the humanitarian and cultural devastation in Europe caused by the Nazis, the international community promulgated a series of international humanitarian conventions. Cultural property protection was now separated into its own distinct convention: the 1954 Hague Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property during Armed Conflict and its First Protocol.

Article 1 of the Convention defines cultural property as

movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people, such as monuments of architecture, art or history, whether religious or secular; archaeological sites; groups of buildings which, as a whole, are of historical or artistic interest; works of art; manuscripts, books and other objects of artistic, historical or archaeological interest; as well as scientific collections and important collections of books or archives…; buildings whose main and effective purpose is to preserve or exhibit the movable cultural property…such as museums, large libraries and depositories of archives, and refuges intended to shelter, in the event of armed conflict, the movable cultural property.…

The two core principles of the Convention are safeguarding of and respect for cultural property.

The first obligation of Parties to the Convention is to “prepare in time of peace for the safeguarding of cultural property situated within their own territory” by taking whatever steps they consider appropriate to protect their cultural property from the foreseeable effects of warfare (Article 3).

The obligation of respect (Article 4) prohibits the use of cultural property for strategic or military purposes if doing so would expose the property to harm during warfare. In addition, States must not target cultural sites and monuments. However, this obligation is subject to a significant exception “in cases where military necessity imperatively requires such a waiver” (Article 4, para. 2). In other words, if attacking a cultural site or monument is necessary to achieve an imperative military goal, then military necessity supersedes, and the protections for cultural property of this article are lost. Unfortunately, the Convention does not define “military necessity,” and some nations have criticized this exception since a fairly low level of necessity could result in destruction or damage to cultural sites and monuments.

Article 4 also imposes an obligation on a Party to the Convention “to prohibit, prevent and, if necessary, put a stop to any form of theft, pillage or misappropriation of, and any acts of vandalism directed against, cultural property” (Article 4, para. 3).

The First Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention also addresses the subject of movable cultural property. However, it does so only under very narrow circumstances of illegal removal of cultural objects from occupied territory and the voluntary deposit of cultural objects by one State in another State for the purpose of safekeeping.

Second Hague Protocol and the Rome Statute

The Second Protocol was adopted in 1999 to clarify some of the provisions of the Hague Convention. For example, it narrows the definition of military necessity and requires States to adopt criminal measures for those who intentionally violate the Convention’s provisions. Other international legal instruments address the protection of cultural property, most particularly the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which classifies intentional destruction of cultural property as a war crime.

An increasing loss

In the post-Second World War period, the appetite of the international art market for works of art, including archaeological objects, grew along with the increase in wealth of the European and North American countries. At the same time, the increasing use of scientific methodologies (including stratigraphic retrieval and scientific analyses) meant that greater quantities of information could be recovered from the proper excavation of sites. As a result, looting caused an increasing loss to our knowledge and understanding of the past. Finally, with the end of colonialism in much of the world, particularly Africa and Asia, the new countries sought legal means to conserve at home what remained of their heritage, after so much had been lost to the colonial powers.

1970 UNESCO Convention

Sparked in particular by the work of Professor Clemency Coggins, who brought world attention to the destruction of Maya architectural and monumental sculptural remains in Central America, the world community under the leadership of UNESCO drafted the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property to confront the illegal trade in art works, antiquities, and ethnographic objects. This Convention makes illicit the import, export, and transfer of cultural property contrary to its provisions. Some countries, such as Germany, Canada, and Australia, prohibit the import of any illegally exported cultural objects. Other countries, such as the United States and Switzerland, prohibit the import of illegally exported archaeological and ethnological materials, as long as there is an additional bilateral agreement in place between themselves and the country of origin.

New resolutions for modern warfare

Both the 2003 Gulf War and the civil war in Syria (2011-present) created opportunities for large-scale destruction and looting of archaeological sites. During the conflict in Syria, Daesh intentionally destroyed ancient structures at the sites of Palmyra in Syria, at Nineveh, Nimrud, and other Neo-Assyrian sites in Iraq, and objects in the Mosul Museum in Iraq. The looting of archaeological sites helped to fund the terrorism and military conflict of Daesh and possibly of the Assad regime in Syria.

In response, the United Nations Security Council enacted a series of Resolutions calling on all member States to prohibit the import of and trade in undocumented archaeological and other cultural materials from Iraq and Syria. These Resolutions have established a new standard for controlling the market for looted archaeological objects, at least within the context of armed conflict. These events have also brought the negative effects of looting and destruction of cultural heritage to the attention of the world community and encouraged countries to take further steps to prevent this destruction.

Additional Resources:

Summary of recent cultural heritage protections (UNESCO)

Kevin Chamberlain, War and Cultural Heritage: A Commentary on the Hague Convention 1954 and its Two Protocols (2nd ed., Builth Wells, UK: Institute of Art and Law, 2013).

C.C. Coggins, “Illicit Traffic of Pre-Columbian Antiquities,” Art Journal 29 (1969), pp. 94-114.

Patty Gerstenblith, Art, Cultural Heritage and the Law (3rd ed., Cary, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press, 2012).

Patty Gerstenblith, “The Destruction of Cultural Heritage: A Crime against Property or a Crime against People?,” John Marshall Review Intellectual Property Law 15 (2016), pp. 336-93.

Patty Gerstenblith and C.R. Smith, “Looting and the Antiquities Market,” Oxford Bibliographies in Classics, edited by Dee Clayman (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

M.P. Kouroupas, “Preservation of Cultural Heritage: A Tool of International Public Diplomacy,” in Cultural Heritage Issues: The Legacy of Conquest, Colonization, and Commerce, edited by James A.R. Nafziger and Ann M. Nicgorski (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff, 2010), pp. 325-334.

K.E. Meyer, The Plundered Past (New York: Athenaeum, 1977).

M.M. Miles, Art As Plunder: The Ancient Origins of the Debate about Cultural Property (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

P.J. O’Keefe, Protecting Cultural Objects: Before and After 1970 (Builth Wells, UK: Institute of Art and Law 2017).

J.F. Witt, Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History (New York: Free Press, 2012).

A race against time: manuscripts and digital preservation

by FATHER COLUMBA STEWART, OSB and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): A conversation with Father Columba Stewart, OSB, executive director of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (Collegeville, Minnesota) and Dr. Beth Harris

Provenance and the Antiquities Market

The increasing importance of provenance: three lawsuits

Three high profile lawsuits in the early 2000s had a strong impact on how the market for antiquities has valued provenance (the record of ownership of a work of art or an antique). The first case concerned the prosecution of New York antiquities dealer Frederick Schultz, who had been trafficking antiquities out of Egypt camouflaged as cheap souvenirs. The second one concerned the prosecution by the Italian federal government of Giacomo Medici, who supplied the world’s most important museums with classical antiquities. The third one involved legal action against one of his regular clients — then J. Paul Getty museum curator Marion True — for purchasing material she knew was illegally excavated from dubious dealers (including Giacomo Medici). The combined effect of these three cases was to force collectors and sellers active in the antiquities market to reevaluate the importance of provenance.

1970 UNESCO Convention

Even though the international community had sent a strong signal condemning the illicit trade in antiquities with the passing of the 1970 UNESCO Convention, this measure never truly impacted the market, because its principles could only be invoked by local courts if they were ratified into the national law of individual member states. For instance, the United States passed legislation covering the substance of the 1970 Convention with the passing of the Cultural Property Implementation Act of 1983, which enabled the negotiation of bilateral agreements with other UNESCO member states restricting the importation of undocumented antiquities coming from their territories. Currently, bilateral agreements with 23 countries are in place, including Italy (2001), Greece (2011), Egypt (2016), Syria (2016) and Iraq (2004).

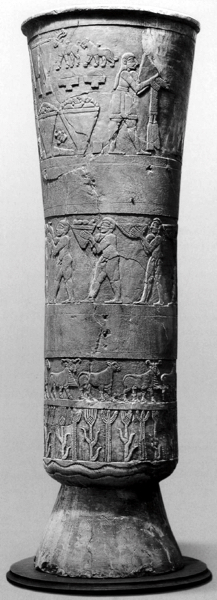

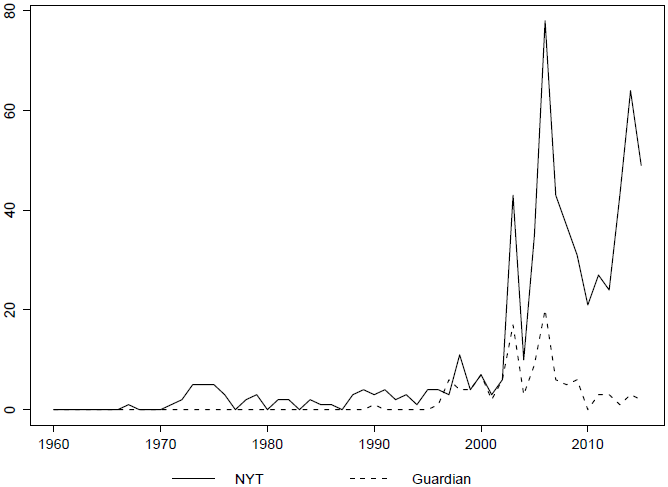

The graph below, which tracks the mention of “looted antiquities” or synonyms in The New York Times and The Guardian, show that it took several decades for the 1970 UNESCO Convention and illegal trade in antiquities to attract public notice. The first substantial spike coincided with a major political event: the 2003 Iraq invasion, when the U.S. army was criticized for the lack of training in the protection of cultural heritage. It was this lack of training (among other things), that ultimately enabled the looting of Iraqi archeological sites as well as the museum in Baghdad — causing the dispersion of thousands of objects, including widely studied works of cultural heritage such as the Sumerian Warka Vase.

1. Frederick Schutz and the trafficking of Egyptian cultural property

2003 was the year Frederick Schultz, a New York gallery owner specializing in Egyptian antiquities, was prosecuted for the illicit trafficking of Egyptian cultural property. The courts held that a patrimony law passed in 1983 made Egypt the legal owner of antiquities found on its territory, and that by smuggling and reselling antiquities looted from its ground, Schultz was guilty of trading stolen property.

In many ways the court utilized the Schultz case to showcase that (notwithstanding the lack of preparedness with regards to the looting in Iraq), the U.S. took crimes against cultural heritage seriously — and the final sentence for Schultz was stiff: 33 months in prison and a $50,000 fine.

2. Giacomo Medici and the trafficking of classical antiquities

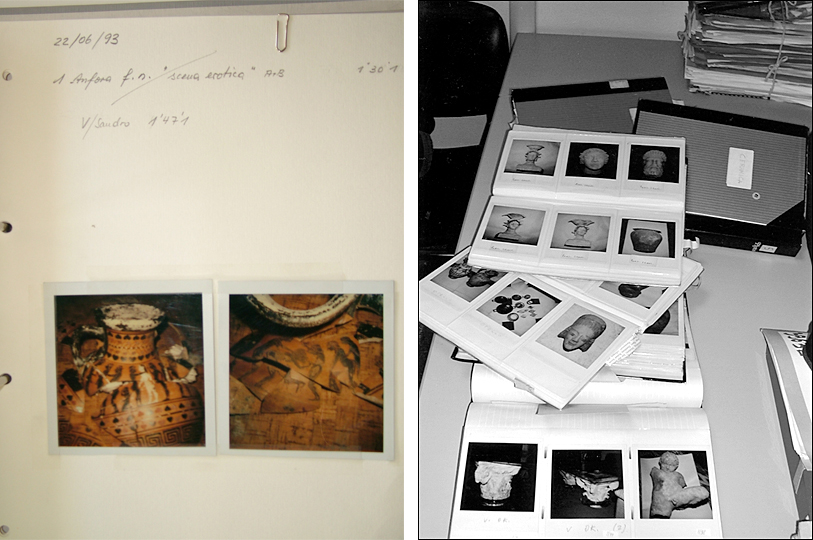

Meanwhile in Rome, prosecutors were gathering evidence to incriminate Giacomo Medici, a dealer based in Geneva who supplied most of the world’s high-profile museums with classical antiquities coming from Italy. In 2004 the Tribunal in Rome convicted Medici to a 10-year imprisonment term and a EUR 10,0000,000 fine for trafficking thousands of looted objects.

3. Marion True and J. Paul Getty Museum

Evidence that surfaced during the investigation (which included Polaroid photographs outlining Medici’s possessions as well as precise ledgers describing their current locations and buyers), showed that one of his regular clients was Marion True, antiquities curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. True had purchased 42 pieces from him over the years, likely knowing that they were the product of illegal digs (or choosing to turn a blind eye towards that pssibility). She too, was prosecuted by the Italian government for conspiring to launder stolen antiquities, and even though the case was eventually abandoned, the evidence against her was significant enough that she lost her job. The Getty returned the pieces she had purchased from Medici and other dubious dealers, to Italy — including the statue of an Aphrodite that True had purchased for eighteen million dollars.

Overall these cases were incredibly important because they conveyed credible commitments that sanctions for trafficking looted antiquities would be enforced and signaled to market participants that they needed to pay attention to provenance. But what does that mean in practice? What type of provenance information makes an object legitimate within the antiquities market?

Auction houses and provenance considerations

Let’s look at this question from two angles: buyers and sellers. The evolution of the regulation in place at major auction houses is helpful in understanding the steps that such entities have put into place to avoid the risk of reputational harm associated with trading looted antiquities.

Provenance considerations connected to the trade of classical material started surfacing in 1998 (note the small spike in graph 1) when journalist Peter Watson exposed internal practices at Sotheby’s designed to back the trade of illegally exported antiquities. The auction house closed down its London branch as a result, and decided to only trade antiquities from its New York office. However, when the U.S. entered into a bilateral agreement with Italy in 2001, the due diligence efforts in connection with provenance documentation increased. Consignors who were hoping to sell antiquities through Sotheby’s had to present documentation showing that the object was located outside its probable country of origin (Italy in the case of most classical pieces) before the bilateral agreement entered into force, in 2001. Later, as the market became aware of the Medici archive as well as documentation about looted pieces coming from the archives of other dealers (including Robert Symes and Gianfranco Becchina), auction houses had to take further measures to counter threats of illicit trade — because, if looted material previously recorded in one of those archives filtered through such checks, auction houses would get a call asking for the lot to be withdrawn (sometimes they still do).

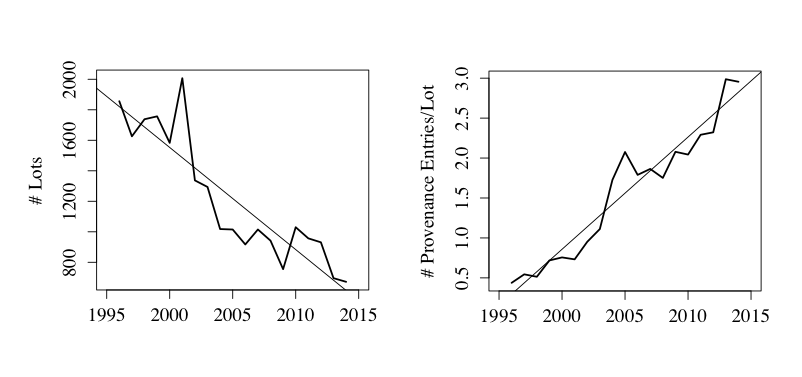

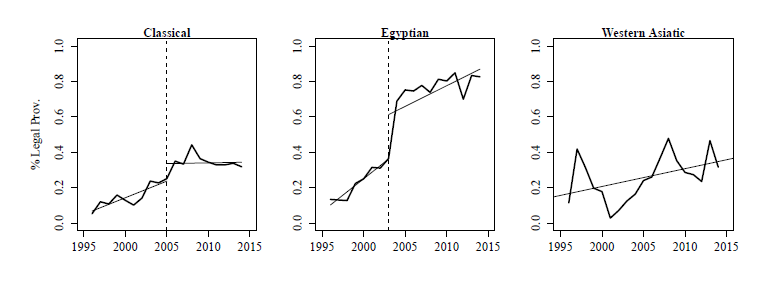

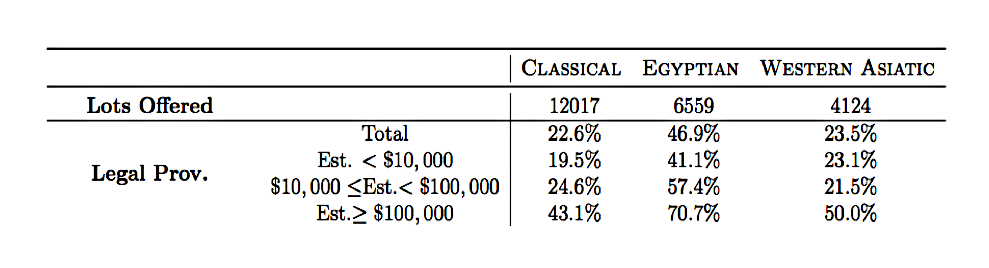

In 2006 Sotheby’s hired Jane Levine, former FBI art crime expert, to run its compliance division and pay specific attention to issues connected to looting, and since then more stringent verification of provenance is being performed. If a claim is made that a specific piece was bought from a particular dealer, the latter will have to present proof (including receipts and other evidence verifying the truthfulness of such statements). As a result, the patterns of antiquities sold at major auction houses have undergone significant changes in the past 20 years, which are noticeable from the graphs below: fewer pieces with better provenance are being sold.

Buyers at these same auctions are valuing provenance more than they have ever done. In the Schultz case, the court made it clear that in order to be legally traded, an ancient object originally from Egypt had to have a verifiable provenance record showing that the piece had either been outside of Egypt since before 1983 or that it comes with an export permit, and indeed since 2003 the pieces sold at auction that meet that criteria have more than doubled. In connection with classical antiquities the situation is trickier because the classical world is spread across many territories that overlap with a number of modern nation states, all of which have different laws. Greece and Italy have had patrimony laws in place condemning the theft of their cultural heritage since the 19th century.

Because of the difficulty with allocating an ancient object to a modern country of origin, and verifying whether its provenance history meets thresholds set out by specific laws, institutional collectors such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum have passed internal guidelines stating that they will generally not acquire an object in the absence of information proving that the piece was outside its country of origin before 1970 (or legally exported from its country of modern discovery after 1970). And again we can see a trend from the above graph verifying that since the Medici prosecution in 2005, more classical antiquities meeting the 1970 threshold are being sold. Table I further corroborates that those items sell for higher prices. The patterns are the same for Western Asiatic antiquities, a category used by auction houses to refer to ancient material coming from the Near East, even though there are no distinguishable linear trends.

Where do we go from here?

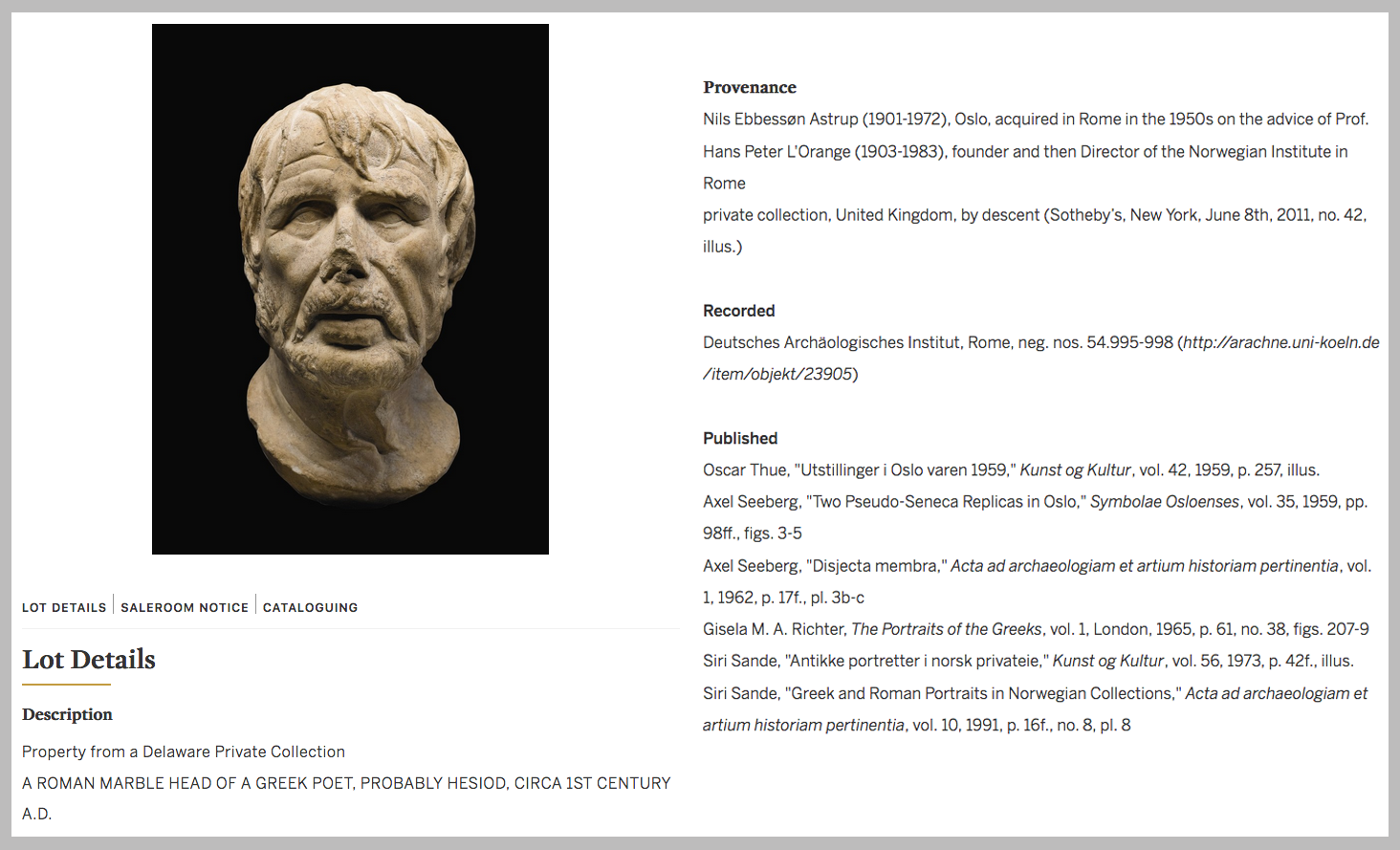

Overall, provenance considerations have become very important in the antiquities context, and it is now unthinkable to purchase a piece of ancient art without performing the necessary due diligence. Museums have to abide by strict regulations and even private collectors are best advised to do so, if they are hoping to resell their collections down the line. Well-provenanced (that is, works that have a long history of ownership), high-quality pieces are few and far between, but they can still be found. Last December Sotheby’s sold a Roman marble head that had been in a private collection in Norway since the 1950s for about $1.5 million. Another convenient avenue for cultural institutions to continue showing and studying antiquities is to enter into collaborations with museums in source countries and negotiate long-term loans in exchange for support with scholarship, conservation, and excavation efforts.

Additional resources:

Market of Mass Destruction Blog

Cultural Heritage Center, U.S. Department of State

Cultural Property Implementation Act of 1983

A NATION AT WAR: THE LOOTING; Experts’ Pleas to Pentagon Didn’t Save Museum (NY Times)

Giacomo Medici (from Trafficking Culture)

Excerpt: ‘The Medici Conspiracy’ (NPR)

Organigram (from Trafficking Culture)

Tempers Heat Up at Trial in Italy on Antiquities (NY Times)

Getty Aphrodite (from Trafficking Culture)

If You Steal It, the Art Vigilante Will Find You (Bloomberg Businessweek)

Fifteen years after looting, thousands of artefacts are still missing from Iraq’s national museum

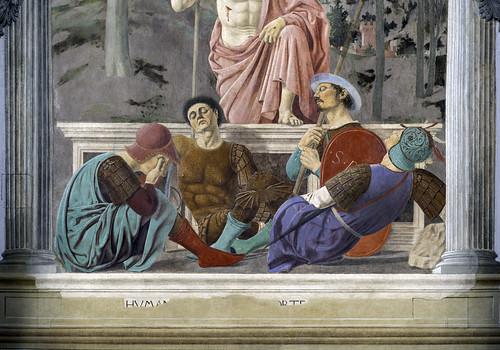

A Renaissance masterpiece nearly lost in war: Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection, c. 1470 (fresco, 225 x 200 cm (Museo Civico, Sansepolcro, Italy)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Saving Torcello, an ancient church in the Venetian Lagoon

by MELISSA CONN, SAVE VENICE and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, Torcello, founded 639, reconstructed 864 and 1008