12.4: Place and identity

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147871

Palmyra: the modern destruction of an ancient city

by DR. SALAM AL KUNTAR and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

City of Palms

Built around an oasis in the Syrian desert, Tadmur or Palmyra, “city of palms,” was one of the most important trade and cultural centers of the ancient world. Palmyra had a distinctive local culture that was incorporated into the Roman Empire in the first century C.E. More than two centuries later, the city gained independence from Rome and under its famous Queen Zenobia established the Palmyrene empire which annexed much of the eastern part of the Roman Empire.

Palmyra stands at the crossroads of civilizations—along the silk routes where merchants traveled between Europe and Asia.

The art and architecture of the city is a perfect portrait of the fertile crescent with its amazing blend of cultures and traditions. A dynamic culture and a land of inherent pluralism owing to its Mesopotamian, Levantine, Semitic, Greco- Roman, Persian, and Islamic heritage.

Palmyra was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 and has a particular place in the Syrian historic consciousness. Syrians take pride in the once-great merchant city that influenced and ultimately defied the power of Rome.

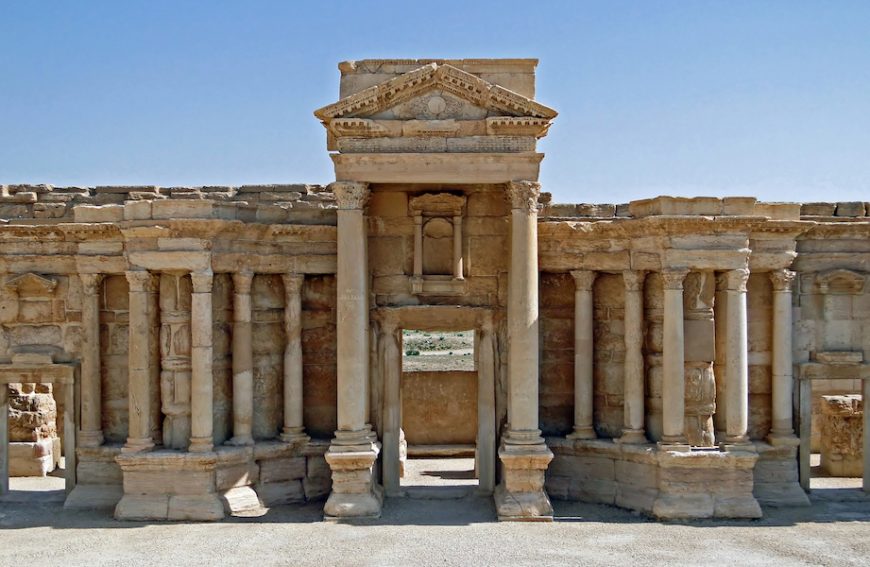

Palmyra’s grand colonnade (above) is a 1,100m long Roman period street that connects a temple to the god Bel with the area known as the Camp of Diocletian. Other archaeological remains in the ancient city of Palmyra include an agora, theatre (below), urban quarters, and other temples that comprise what is generally considered by scholars to be the finest example of surviving Roman architecture in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Also within the archaeological zone of Palmyra stands the Fakhr-al-Din al-Ma’ani Castle. This heavy fortification dates to the 13th century and offers a spectacular view of the site.

Tombs

The affluent residents of ancient Palmyra built elaborate tombs outside the city walls, adorned with portraits of citizens. Bust sculptures of wealthy patrons from Palmyra, dating to the 1st and 2nd centuries C.E., demonstrate the complexity and richness of Palmyrene identity. These busts combine Roman sculptural elements and local stylistic elements. Some of these portraits were accompanied by inscriptions in the Palmyrene dialect of Aramaic.

The Syrian civil war

Both the modern town and ancient city of Palmyra were caught in the crossfire of the Syrian civil war beginning in early 2013. Then in 2014, military forces from the regime of Bashar al-Assad (president of Syria) fortified the site, further damaging the ruins.

In 2015, ISIS overran Palmyra, and committed barbaric and monstrous assaults on the people, cultural monuments, and artifacts of the city. The destruction of Palmyra’s magnificent monuments provoked an international outcry and prompted media attention.

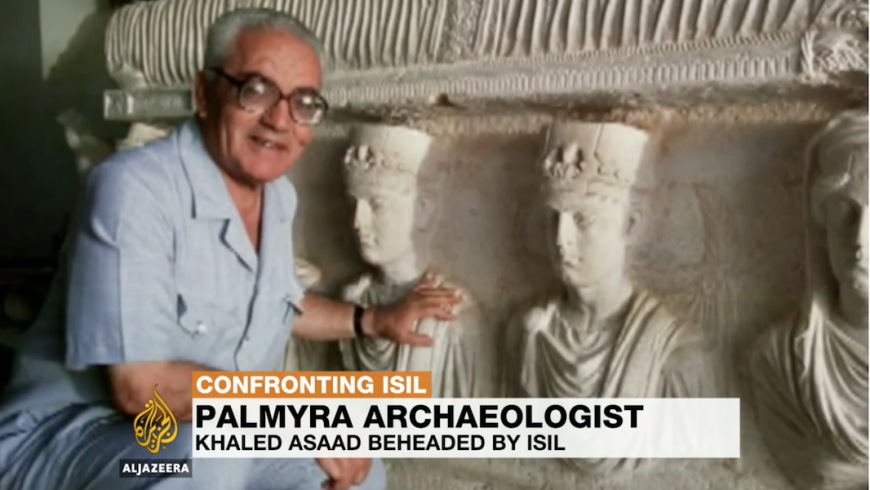

ISIS began by executing Khaled Al-Ass’ad, the former Director of Antiquities at Palmyra, a devoted and outstanding archeologist who loved Palmyra like no one else. Following this horrific execution, ISIS began to destroy many of the most famous ruins—the Bel and Baalshamin temples, the tower tombs, the monumental arch and standing columns in addition to plundering the Palmyra Museum and destroying a large number of sculptures and artifacts left there.

In March 2016, the Assad forces (backed by the Russian military) recaptured Palmyra and immediately started building a Russian military base within the World Heritage Site. ISIS recaptured Palmyra in early December 2016 and destroyed the tetrapylon and damaged the theater. The Assad regime forces managed to take Palmyra back in March 2017.

Looting and propoganda in Palmyra

The ancient site also witnessed extensive looting and many Palmyrene artifacts appeared on the antiquities market or were captured by Lebanese and Turkish customs officials. Looting started in the fall of 2011, when the Assad regime lost control of the town. Then, during the ISIS occupation, the so-called Diwan al Rikaz office was established which gave digging permits in exchange for paying a tax. The permit was for non-figurative objects only (presumably objects with human figures were to be destroyed by ISIS fighters). However, the looters are believed to have handed over only unsellable figurative objects to the Diwan al Rikaz, hiding from ISIS artifacts in good condition that could be sold to dealers.

Throughout these episodes where control shifted between the forces of the Assad regime and ISIS, Palmyra, its monuments, and artifacts were used to reinforce the appalling political propaganda being disseminated. In late 2015, ISIS used the ancient theater to stage dramatic executions for circulation on social media. Soon after, the Russian military staged a musical concert at the same theater to promote an image of a civilized Russian savior, only to leave ISIS to capture the city nine months later with little fighting. Syrian cultural heritage, including that of Palmyra, should play a reconciling and unifying role in post-conflict Syria. Syrian cultural heritage should not be used in the political or sectarian agenda of the groups fighting in the Syrian conflict.

Restoring Palmyra

In May 2016, when ISIS was first driven from Palmyra, there were numerous calls, led by UNESCO, to begin the work of restoring the ancient city despite the fragile security conditions. Millions of Syrians are still suffering from the consequences of the bloody war. Among them are the people of Palmyra, who continue to experience grave risks, including detention by the Assad government, and the destruction of their homes and heritage.

When the day for the reconstruction of Palmyra comes—after the conflict is over—it will require a period of reflection about what should be reconstructed, how it should be rebuilt, and how the recent events of the war and occupation by ISIS should be memorialized—if at all. This discussion must be undertaken by Syrians on all sides of the conflict, and not decided for Syria by international organizations.

The question of 3D models

A new development in the documentation of heritage sites has been the application of new technologies to create 3D online libraries of the world’s important cultural heritage sites and a number of projects have recently worked to create a 3D models of Palmyra’s lost monuments. The Institute for Digital Archaeology at the University of Oxford has created a 3D model of the destroyed triumphal arch using structure-from-motion photogrammetry.

The 3-D printed arch was displayed in London, New York, and other cities, prompting a debate about the purpose of such reconstructions and their display—especially given that the reproduction failed to capture the authenticity of the original structure and that the project revealed a disconnection with the Syrian people and the inhabitants of Palmyra, who have lived alongside these monuments for many generations.

Additional resources:

Ben Taub, “The Real Value of the Isis Antiquities Trade,”The New Yorker, December 4, 2015.

The site of Palmyra on UNESCO’s World Heritage List

Should we 3D print a new Palmyra?, The Conversation, March 31, 2016.

About the Silk Road (from UNESCO)

Institute for Digital Archaeology, Oxford University and the Triumphal Arch at Palmyra

Ancient Babylon: excavations, restorations and modern tourism

by LISA ACKERMAN and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): This video was produced in cooperation with the World Monuments Fund. A conversation with Lisa Ackerman and Beth Harris.

Venice’s San Marco, a mosaic of spiritual treasure

by DR. ELIZABETH RODINI and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): The Porta Sant’Alipio Mosaic, c. 1270-75, Basilica San Marco, Venice, an ARCHES video speakers: Dr. Elizabeth Rodini, Andrew Heiskell Arts Director at American Academy in Rome and Dr. Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Renaissance Synagogues of Venice

by DR. DAVID LANDAU, DR. MARCELLA ANSALDI and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): German Synagogue (founded 1528), the Italian Synagogue (founded 1575), the Canton Synagogue (1532), and the Jewish Museum, Venice, This is an ARCHES video with Dr. David Landau, Dr. Marcella Ansaldi, Director of the Jewish Museum of Venice, and Dr. Steven Zucker

The 16th century synagogues of Venice need your support. Donations to the the Jewish Community of Venice can be made here: jvenice.org/en/donations. Or you can email the American Friends of the Jewish Community of Venice here: info@afjcv.org

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Unearthing the Aztec past, the destruction of the Templo Mayor

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Unearthing the Aztec past, the destruction of the Templo Mayor (Mexico City) . Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker

In 1978, electrical workers in Mexico City came across a remarkable discovery. While digging near the main plaza, they found a finely carved stone monolith that displayed a dismembered and decapitated woman. Immediately, they knew they found something special. Shortly thereafter, archaeologists realized that the monolith displayed the Mexica (Aztec)¹ goddess Coyolxauhqui, or Bells-Her-Cheeks, the sister of the Mexica’s patron god, Huitzilopochtli (Hummingbird-Left), who killed his sister when she attempted to kill their mother. This monolith led to the discovery of the Templo Mayor, the main Mexica temple located in the sacred precinct of the former Mexica capital, known as Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City).

The Templo Mayor

The city of Tenochtitlan was established in 1325 on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco (much of which has since been filled in to accommodate Mexico City which now exists on this site), and with the city’s foundation the original structure of the Templo Mayor was built. Between 1325 and 1519, the Templo Mayor was expanded, enlarged, and reconstructed during seven main building phases, which likely corresponded with different rulers, or tlatoani (“speaker”), taking office. Sometimes new construction was the result of environmental problems, such as flooding.

Located in the sacred precinct at the heart of the city, the Templo Mayor was positioned at the center of the Mexica capital and thus the entire empire. The capital was also divided into four main quadrants, with the Templo Mayor at the center. This design reflects the Mexica cosmos, which was believed to be composed of four parts structured around the navel of the universe, or the axis mundi.

The Templo Mayor was approximately ninety feet high and covered in stucco. Two grand staircases accessed twin temples, which were dedicated to the deities Tlaloc and Huitzilopochti. Tlaloc was the deity of water and rain and was associated with agricultural fertility. Huitzilopochtli was the patron deity of the Mexica, and he was associated with warfare, fire, and the Sun.

Paired together on the Templo Mayor, the two deities symbolized the Mexica concept of atl-tlachinolli, or burnt water, which connoted warfare—the primary way in which the Mexica acquired their power and wealth.

The Huitzilopochtli Temple

In the center of the Huitzilopochtli temple was a sacrificial stone. Near the top, standard-bearer figures decorated the stairs. They likely held paper banners and feathers. Serpent balustrades adorn the base of the temple of Huitzilopochtli, and two undulating serpents flank the stairs that led to the base of the Templo Mayor as well.

But by far the most famous object decorating the Huiztilopochtli temple is the Coyolxauhqui monolith, found at the base of the stairs. Originally painted and carved in low relief, the Coyolxauhqui monolith is approximately eleven feet in diameter and displays the female deity Coyolxauhqui, or Bells-on-her-face. Golden bells decorate her cheeks, feathers and balls of down adorn her hair, and she wears elaborate earrings, fanciful sandals and bracelets, and a serpent belt with a skull attached at the back. Monster faces are found at her joints, connecting her to other female deities—some of whom are associated with trouble and chaos. Otherwise, Coyolxauhqui is shown naked, with sagging breasts and a stretched belly to indicate that she was a mother. For the Mexica, nakedness was considered a form of humiliation and also defeat. She is also decapitated and dismembered. Her head and limbs are separated from her torso and are organized in a pinwheel shape. Pieces of bone stick out from her limbs.

The monolith relates to an important myth: the birth of the Mexica patron deity, Huitzilopochtli. Apparently, Huitzilopochtli’s mother, Coatlicue (Snakes-her-skirt), became pregnant one day from a piece of down that entered her skirt. Her daughter, Coyolxauhqui, became angry when she heard that her mother was pregnant, and together with her 400 brothers (called the Centzonhuitznahua) attacked their mother. At the moment of attack, Huitzilopochtli emerged, fully clothed and armed, to defend his mother on the mountain called Coatepec (Snake Mountain). Eventually, Huitzilopochtli defeated his sister, then beheaded her and threw her body down the mountain, at which point her body broke apart.

The monolith portrays the moment in the myth after Huitzilopochtli vanquished Coyolxauhqui and threw her body down the mountain. By placing this sculpture at the base of Huiztilopochtli’s temple, the Mexica effectively transformed the temple into Coatepec. Many of the temple’s decorations and sculptural program also support this identification. The snake balustrades and serpent heads identify the temple as a snake mountain, or Coatepec. It is possible that the standard-bearer figures recovered at the Templo Mayor symbolized Huitzilopochtli’s 400 brothers.

Ritual performances that occurred at the Templo Mayor also support the idea that the temple symbolically represented Coatepec. For instance, the ritual of Panquetzaliztli (banner raising) celebrated Huitzilopochtli’s triumph over Coyolxauhqui and his 400 brothers. People offered gifts to the deity, danced and ate tamales. During the ritual, war captives who had been painted blue were killed on the sacrificial stone and then their bodies were rolled down the staircase to fall atop the Coyolxauhqui monolith to reenact the myth associated with Coatepec. For the enemies of the Mexica and those people the Mexica ruled over, this ritual was a powerful reminder to submit to Mexica authority. Clearly, the decorations and rituals associated with the Templo Mayor connoted the power of the Mexica empire and their patron deity, Huitzilopochtli.

The Tlaloc Temple

At the top center of the Tlaloc temple is a sculpture of a male figure on his back painted in blue and red. The figure holds a vessel on his abdomen likely to receive offerings. This type of sculpture is called a chacmool, and is older than the Mexica. It was associated with the rain god, in this case Tlaloc.

At the base of the Tlaloc side of the temple, on the same axis as the chacmool, are stone sculptures of two frogs with their heads arched upwards. This is known as the Altar of the Frogs. The croaking of frogs was thought to herald the coming of the rainy season, and so they are connected to Tlaloc.

While Huiztilopochtli’s temple symbolized Coatepec, Tlaloc’s temple was likely intended to symbolize the Mountain of Sustenance, or Tonacatepetl. This fertile mountain produced high amounts of rain, thereby allowing crops to grow.

Offerings at the Templo Mayor

Over a hundred ritual caches or deposits containing thousands of objects have been found associated with the Templo Mayor. Some offerings contained items related to water, like coral, shells, crocodile skeletons, and vessels depicting Tlaloc. Other deposits related to warfare and sacrifice, containing items like human skull masks with obsidian blade tongues and noses and sacrificial knives. Many of these offerings contain objects from faraway places—likely places from which the Mexica collected tribute. Some offerings demonstrate the Mexica’s awareness of the historical and cultural traditions in Mesoamerica. For instance, they buried an Olmec mask made of jadeite, as well as others from Teotihuacan (a city northeast of modern-day Mexico City known for its huge monuments and dating roughly from the 1st century until the 7th century C.E.). The Olmec mask was made over a thousand years prior to the Mexica, and its burial in Templo Mayor suggests that the Mexica found it precious and perhaps historically significant.

The Templo Mayor today

After the Spanish Conquest in 1521, the Templo Mayor was destroyed, and what did survive remained buried. The stones were reused to build structures like the Cathedral in the newly founded capital of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (1521-1821). If you visit the Templo Mayor today, you can walk through the excavated site on platforms. The Templo Mayor museum contains those objects found at the site, including the recent discovery of the largest Mexica monolith showing the deity Tlaltecuhtli.

1. The Aztec referred to themselves as Mexica

Additional resources:

Virtual Tour of the Templo Mayor museum (in Spanish)

The Templo Mayor and its Symbolism (Guggenheim Museum)

Templo Mayor on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Aztec World, ed. By Elizabeth Baquedano and Gary M. Feinman (New York: Abrams in association with the Field Museum, 2008).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Unearthing New York’s history of slavery

by DR. RENÉE ATER and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Rodney Leon, African Burial Ground National Monument, 2006, New York City, an ARCHES video, speakers Dr. Renée Ater and Dr. Steven Zucker

Seneca Village: the lost history of African Americans in New York

by DR. DIANA DIZEREGA WALL and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): A conversation between Dr. Diana Wall and Dr. Steven Zucker in Central Park about Seneca Village

If you are a descendant of a Seneca Village resident, or know someone who is, please contact the Seneca Village Project at: diana.diz.wall[at]gmail.com.

A Smarthistory ARCHES video

Additional resources:

The Seneca Village Project (Columbia University)

Seneca Village Site (from the Central Park Conservancy)

Ceremonial belt (Kwakwaka’wakw)

by DR. AARON GLASS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Ceremonial belt (Kwakwaka’wakw), late 19th century, wood, cotton, paint, and iron (Field Museum, Chicago), an ARCHES video. Special thanks to Aaron Glass, the Bard Graduate Center, the U’mista Cultural Centre, and Corrine Hunt

Voyage to the moai of Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

by DR. WAYNE NGATA and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Easter Island is world famous, but local people are only now reasserting control over their history.

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Moai of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Waka Tapu, and the reclaiming of cultural heritage