12.3: Ruins, reconstruction, and renewal

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147870

The Parthenon, as it appears today on the summit of the Acropolis, seems like a timeless monument—one that has been seamlessly transmitted from its moment of creation, some two and a half millennia ago, to the present. But this is not the case. In reality, the Parthenon has had instead a rich and complex series of lives that have significantly affected both what is left, and how we understand what remains.

It is illuminating to examine the Parthenon’s ancient lives: its genesis in the aftermath of the Persian sack of the Acropolis in 490 B.C.E.; its accretions in the Hellenistic and Roman eras; and its transformation as the Roman empire became Christian. Why was the building created, and how was it understood by its first viewers? How did its meanings change over time? And why did it remain so important, even in Late Antiquity, that it was converted from a polytheist temple into a Christian church?

Investigating the many lives of the Parthenon has much to tell us about how we perceive (and misperceive) this famous ancient monument. It is also relevant to broader debates about monuments and cultural heritage. In recent years, there have been repeated calls to tear down or remove contested monuments, for instance, statues of Confederate generals in the southern United States. While these calls have been condemned by some as ahistorical, the experience of the Parthenon offers a different perspective. What it suggests is that monuments, while seemingly permanent, are in fact regularly altered; their natural condition is one of adaptation, transformation, and even destruction.

The Genesis of the Parthenon, 480–432 BCE

The Parthenon we see today was not created ex novo. Instead, it was the final monument in a series, with perhaps as many as three Archaic predecessors. The penultimate work in this series was a marble building, almost identical in scale and on the same site as the later Parthenon, initiated in the aftermath of the First Persian War.

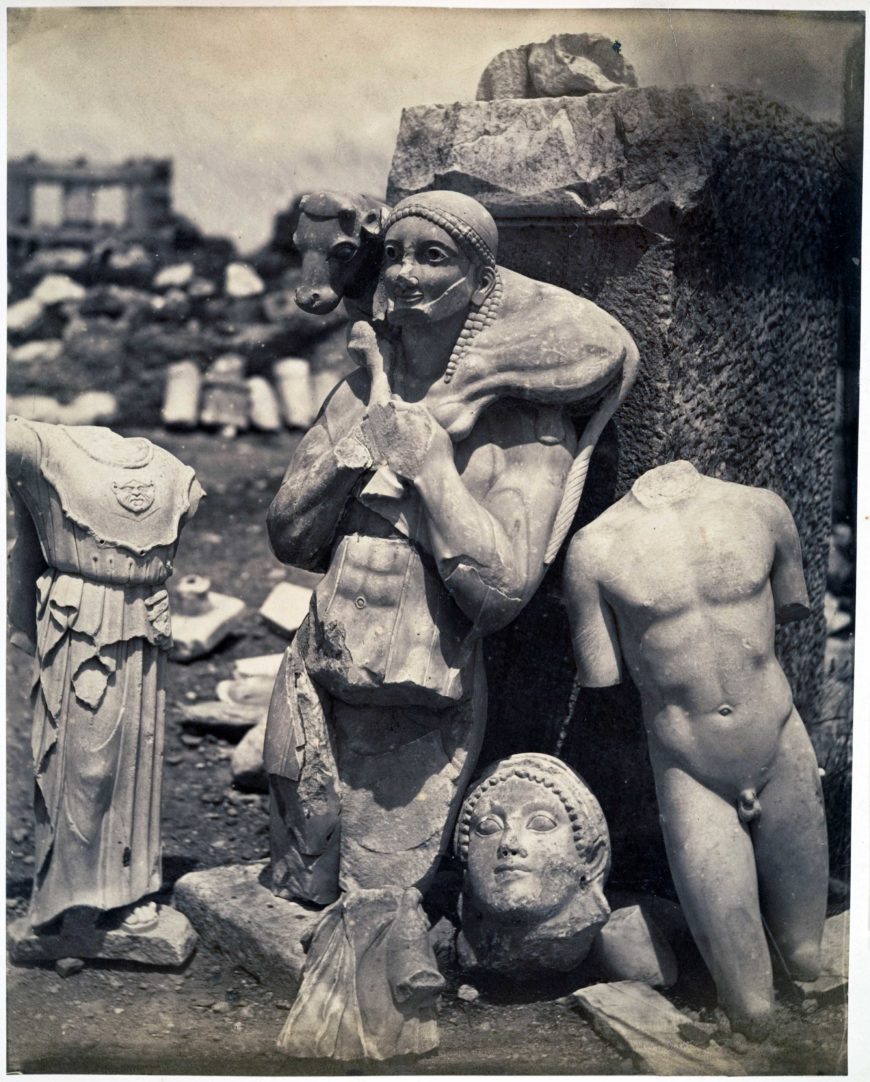

In the war in 492–490 B.C.E., Athens played a central role in the defeat of the Persians. Thus it is not surprising that ten years later when the Persians returned to Greece, they made for Athens; nor that, when they took the city, they sacked it with particular fervor. In the sack, they paid special attention to the Acropolis, Athens’s citadel. The Persians not only looted the rich sanctuaries at the summit, but also burned buildings, overturned statues, and smashed pots.

When the Athenians returned to the ruins of their city, they faced the question of what to do with their desecrated sanctuaries. They had to consider not only how to commemorate the destruction they had suffered, but also how to celebrate, through the rebuilding, their eventual victory in the Persian Wars.

The Athenians found no immediate solution to their challenge. Instead, for the next thirty years they experimented with a range of strategies to come to terms with their history. They left the temples themselves in ruins, despite the fact that the Acropolis continued to be a working sanctuary. They did, however, rebuild the walls of the citadel, incorporating within them some fire-damaged materials from the destroyed temples. They also created a new, more level surface on the Acropolis through terracing; in this fill, they buried all the sculptures damaged in the Persian sack. These actions, most likely initiated in the immediate aftermath of the destruction, were the only major interventions on the Acropolis for over thirty years.

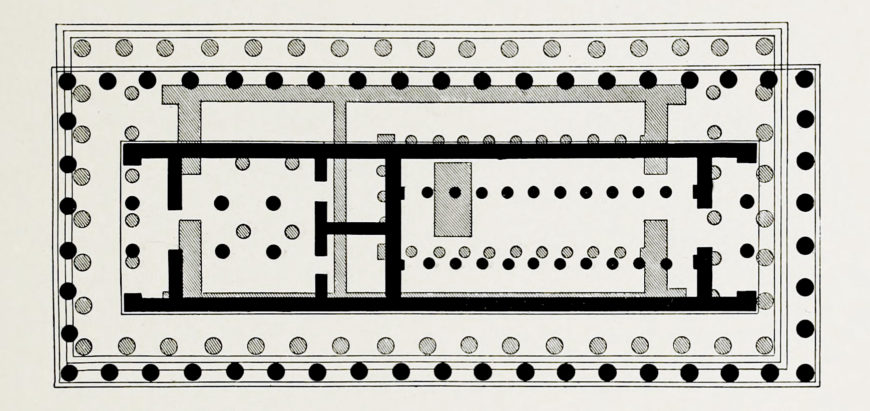

In the mid-fifth century B.C.E., the Athenians decided, finally, to rebuild. On the site of the great marble temple burned by the Persians, they constructed a new one: the Parthenon we know today. They set it on the footprint of the earlier building, with only a few alterations; they also re-used in its construction every block from the Older Parthenon that had not been damaged by fire. In their recycling of materials, the Athenians saved time and expense, perhaps as much as one-quarter of the cost of construction.

At the same time, their re-use had advantages beyond the purely pragmatic. As they rebuilt on the footprint of the damaged temple and re-used its blocks, the Athenians could imagine that the Older Parthenon was reborn—larger and more impressive, but still intimately connected to the earlier sanctuary.

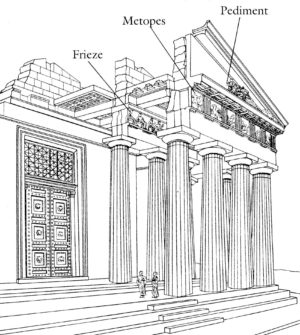

While the architecture of the Parthenon referenced the past through re-use, the sculptures on the building did so more allusively, re-telling the history of the Persian Wars through myth. This re-telling is clearest on the metopes that decorated the exterior of the temple. These metopes had myths, for instance, the contest between men and centaurs, that recast the Persian Wars as a battle between good and evil, civilization and barbarism.

The metopes did not, however, depict this battle as one of effortless victory. Instead, they showed the forces of civilization challenged and sometimes overcome: men wounded, struggling, even crushed by the barbaric centaurs. In this way, the Parthenon sculptures allowed the Athenians to acknowledge both their initial defeat and their eventual victory in the Persian Wars, distancing and selectively transforming history through myth.

Thus even in what might commonly be understood as the moment of genesis for the Parthenon, we can see the beginning of its many lives, its shifting significance over time. Left in ruins from 480 to 447 B.C.E., it was a monument directly implicated in the devastating sack of the Acropolis at the onset of the Second Persian War. As the Parthenon was rebuilt over the course of the following fifteen years, it became one that celebrated the successful conclusion to that war, even while acknowledging its suffering. This transformation in meaning presaged others to come, more nuanced and then more radical.

Hellenistic and Roman Adaptations

By the Hellenistic era if not before, the Parthenon had taken on a canonical status, appearing as an authoritative monument in a manner familiar to us today. It was not, however, untouchable. Instead, precisely because of its authoritative status, it was adapted, particularly by those who sought to present themselves as the inheritors of Athens’ mantle.

The Parthenon was altered by a series of aspiring monarchs, both Hellenistic and Roman. Their goal was to pull the monument, anchored in the canonical past, toward the contemporary. They did so above all by equating later victories with Athens’ now-legendary struggles against the Persians.

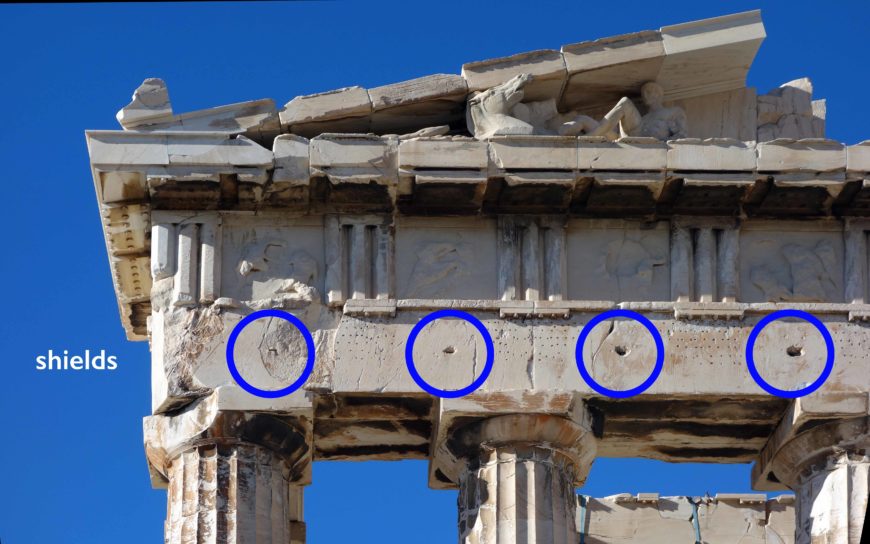

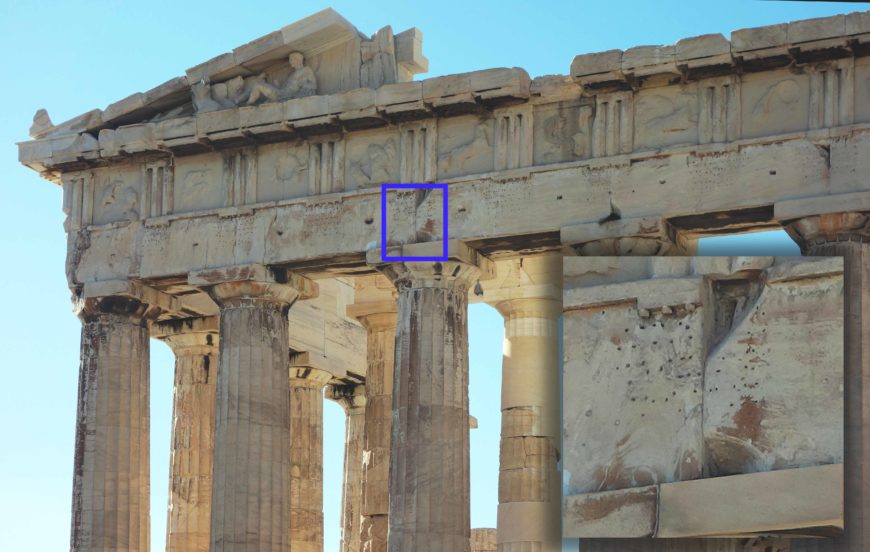

The first of these aspiring monarchs was the Macedonian king Alexander the Great. As he sought to conquer the Achaemenid Empire—alleging, as one casus belli, the Persian destruction of Greek sanctuaries one hundred and fifty years earlier—Alexander made good propagandistic use of the Parthenon. After his first major victory over the Persians in 334 B.C.E., the Macedonian king sent to Athens three hundred suits of armor and weapons taken from his enemies. Likely with Alexander’s encouragement, the Athenians used them to adorn the Parthenon. There are still faint traces of the shields, once prominently placed just below the metopes on the temple’s exterior. Melted down long ago due to their valuable metal content, the shields must have been a highly visible memento of Alexander’s victory—and also of Athens’ subordination to his rule.

Some two centuries later, another Hellenistic monarch set up a larger and more artistically ambitious dedication on the Acropolis. Erected just to the south of the Parthenon, the monument celebrated the Pergamene kings’ victory over the Gauls in 241 B.C.E. It also suggested that this recent success was equivalent to earlier mythological and historical victories, with monumental sculptures that juxtaposed Gallic battles with those of gods and giants, men and Amazons, and Greeks and Persians. Like the shield dedication of Alexander, the Pergamene monument made good use of its placement on the Acropolis. The dedication highlighted connections between the powerful new monarchs of the Hellenistic era and the revered city-state of Athens, paying homage to Athens’ history while appropriating it for new purposes.

A final royal intervention to the Parthenon came in the time of the Roman emperor Nero. This was an inscription on the east facade of the Parthenon, created with large bronze letters in between Alexander’s previously dedicated shields. The inscription recorded Athen’s vote in honor of the Roman ruler, and was likely put up in the early 60s C.E.; it was subsequently taken down following Nero’s assassination in 68. The inscription honored Nero by connecting him to Athens and to Alexander the Great, a model for the young philhellenic emperor. Its removal offered a different message. It was a deliberate and very public erasure of the controversial ruler from the historical record. In this, Nero’s inscription (and its removal) was perhaps the most striking rewriting of the Parthenon’s history—at least until Christian times.

Reviewing the Hellenistic and Roman adaptations of the Parthenon, it is easy to see them purely as desecrations: appropriations of a religious monument for political and propagandistic purposes. And the speedy removal of Nero’s inscription does support this reading, at least for the visually aggressive strategies of the Roman emperor. At the same time, the changes of the Hellenistic and Roman eras are also testimony to the continued vitality of the sanctuary. Due to the prestige of the Parthenon, formidable monarchs sought to stake their visual claims to power on what was by now a very old monument, over four centuries old by the time of Nero. By altering the temple and updating its meanings, they kept it young.

Early Christian Transformations

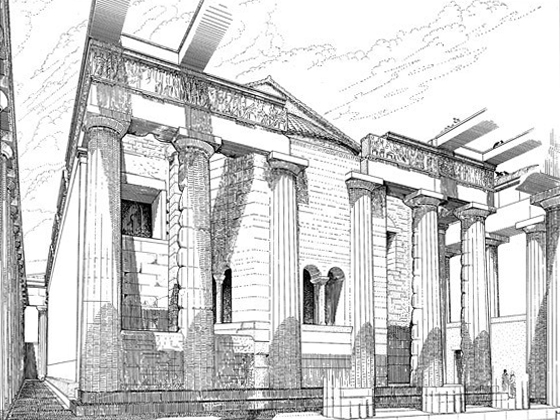

In ancient times, the most radical and absolute transformation of the Parthenon came as the Roman empire became Christian. At that point, the temple of Athena Parthenos was turned into an Early Christian church dedicated to the Theotokos (Mother of God). As with the rebuilding of the Parthenon in the mid-fifth century B.C.E., the decision to put a Christian church on the site of Athena’s temple was not just pragmatic but programmatic.

By transforming the polytheist sanctuary into a space of Christian worship, it provided a clear example of the victory of Christianity over traditional religion. At the same time, it also effectively removed, through re-use, an important and long-enduring center of polytheist cult. This removal through re-use was a characteristic strategy used by the Christians throughout the Roman Empire, from Turkey to Egypt to the German frontier. In all these places, it formed part of the often violent, yet imperially sanctioned, transition from polytheism to Christianity.

The Christian transformation of the Parthenon involved considerable adaptation of its architecture. The Christians needed a large interior space for congregation, unlike the polytheists, whose most important ceremonies took place at a separate altar, outdoors. To repurpose the building, the Christians renovated the inner cella of the Parthenon. They detached it from its exterior colonnade, added an apse that broke through the columns at the east end, and removed from the interior the statue of Athena Parthenos that had been the raison d’étre of the polytheist temple.

Other sculptures from the Parthenon suffered likewise from the Christians’ attentions. Most of the metopes—the lowest down and most visible of the Parthenon’s sculptures—were cut away, rendering them difficult to interpret or to use as a focus of polytheist cult. Only the south metopes with the centaurs were spared, perhaps because they overlooked the edge of the Acropolis and were thus hard to see. By contrast, the frieze (hidden between the exterior and interior colonnades) was left almost entirely intact, as were the high-up pediments. The differentiated treatment of the various sculptures on the Parthenon suggests negotiation between traditionalists and the more fervent of the contemporary Christians. Polytheists perhaps sacrificed the relatively small-scale and blatantly mythological metopes to keep the larger, better quality sculptures elsewhere on the monument. Examining the frieze, about one hundred sixty meters long and almost perfectly preserved, it seems like the polytheists got a good deal.

Conclusions

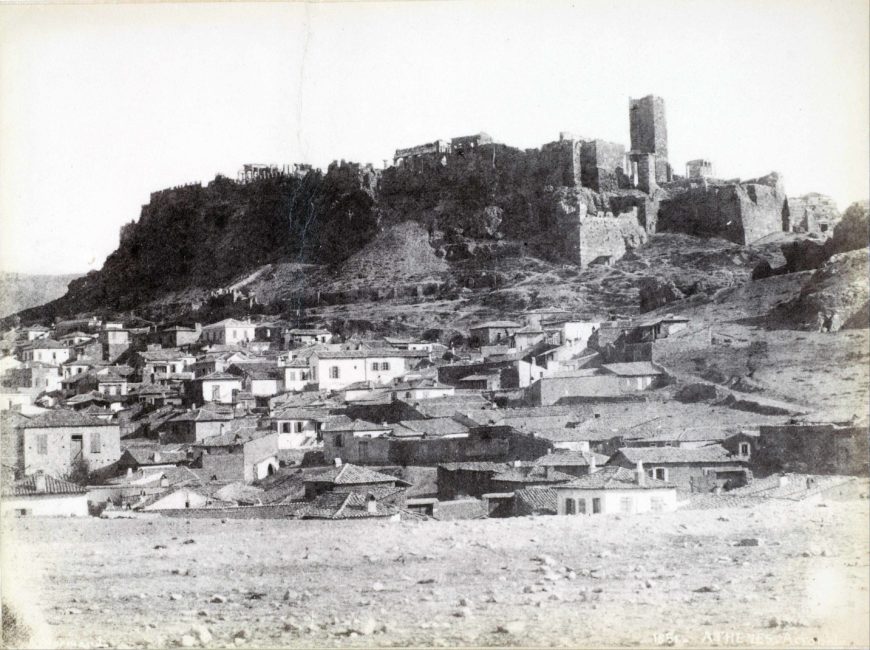

Within and beyond the ancient world, the Parthenon had many lives. Rather than ignoring them, it is useful to acknowledge these lives as contributions to the building’s extraordinary continuing vitality. At the same time, one might note that the biography of the Parthenon (though accessible to specialists) has been decidedly effaced by the way it is presented now. When contrasting its present-day state with the first photographs taken in the mid-nineteenth century, we can see how much has been intentionally removed: a Frankish tower by the entrance to the Acropolis, an Ottoman dome, mundane habitations.

In its current iteration, the Acropolis has been returned to something resembling its pristine Classical condition, with no reconstructed monuments dating later than the end of the 5th century B.C.E. This feels like a loss: a retardataire effort to reinstate a selective, approved version of the past and to erase the traces of a more difficult and complex history. As such it stands as an example, and perhaps also a warning, for our current historical moment.

Additional resources

Jeffrey Hurwit, The Athenian Acropolis: History, mythology, and archaeology from the Neolithic era to the present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Rachel Kousser, “Destruction and memory on the Athenian Acropolis,” Art Bulletin 91, no. 3 (2009): pp. 263–82

R. R. Smith, “Defacing the gods at Aphrodisias.” In Historical and Religious Memory in the Ancient World, edited by R. R. R. Smith and B. Dignas (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 202), pp. 282–326

Views of past and present: the Forum Romanum and archaeological context

Views of Rome have long fired human imagination, eliciting reactions that lead to contemplation and argue for conservation.

Views of Rome

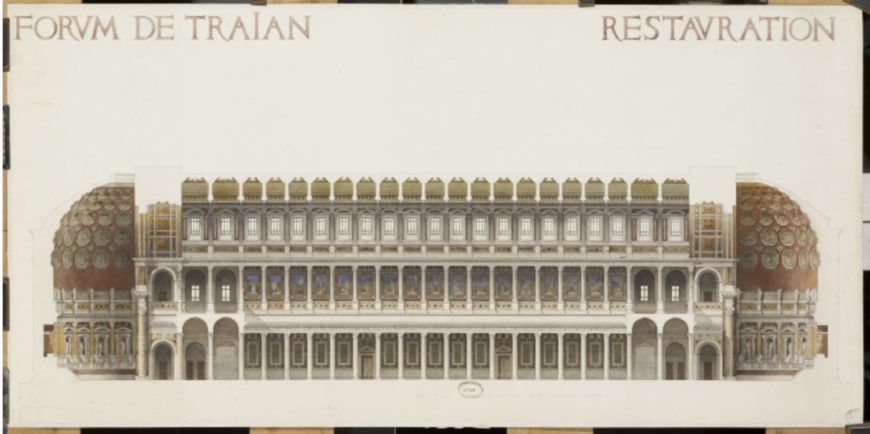

The Roman emperor Constantius II (the second son of Constantine the Great) visited Rome for the only time in his life in the year 357 C.E. His visit to the city included a tour of the usual monuments and sites, but the majesty of the Basilica Ulpia still standing in the forum built by the emperor Trajan arrested his attention, causing him to declare that the monument was so grand that it would be impossible to imitate it (Ammianus Marcellinus Rerum Gestarum 16.15). From a certain point of view, any visitor to Rome can share the experience and reaction of Constantius II.

The city’s monuments (and their ruins) are cues for memory, discourse, and discovery. Their rediscovery and subsequent interpretation in modern times play a key role in our understanding of the past and influence the role that the past plays in the present. For these reasons, among others, it is crucial that we think critically about fragmented past landscapes and that any reading of fragments is contextualized, nuanced, and transparent in its motives. The physical presence of fragments raises the question of whether or not the past is knowable. Tangible ruins and artifacts suggest that it is, but whose story are we telling when we analyze and interpret these remains? If we consider a quintessentially famous and evocative archaeological landscape like the Forum Romanum (Roman Forum) in Rome we have an opportunity to examine a fragmented past landscape and also to explore the question of what role archaeology plays in understanding and interpreting the past.

From heart of empire to pasturage for cows

The story of the Forum as an important node of cultural significance was central to ancient Roman ideation about their city and even themselves. Romans could define themselves in relation to the places where they believed key past events had occurred. The fact that this tradition provided the backdrop for the Forum’s activities works to heighten the efficacy and the value of constructing collective identity and memory. In ways both practical and symbolic the cramped space sandwiched between the Capitoline and Palatine hills was the heart of the Roman populace.

The Forum witnessed many of the city’s key events. It began as a central point of convergence in the landscape for sacred and civic business and, over time, became a sort of monumentalized and petrified museum of the offices of state and the promotion of state ideology. With the decline of the western Roman empire in the 3rd and 4th centuries C.E., the relevance and importance of the forum square receded. Its structures fell into disuse, were stripped of usable building materials, and repurposed for other uses.

The last purposefully erected monument of the forum is the so-called Column of Phocas, a cannibalized column (it was originally made for another monument). It was erected on August 1st of 608 C.E. in honor of the Eastern Roman Emperor Phocas. Its inscription (CIL VI, 01200) speaks of eternal glory and lasting recognition for the emperor (a statement on monumentality that had long echoed in Latin literature, for instance, Horace Odes 3.30). It is not insignificant that in a much diminished city of Rome it was nonetheless worthwhile to create a new monument (even if using repurposed materials) in the once thriving sacred and civic center of the city.

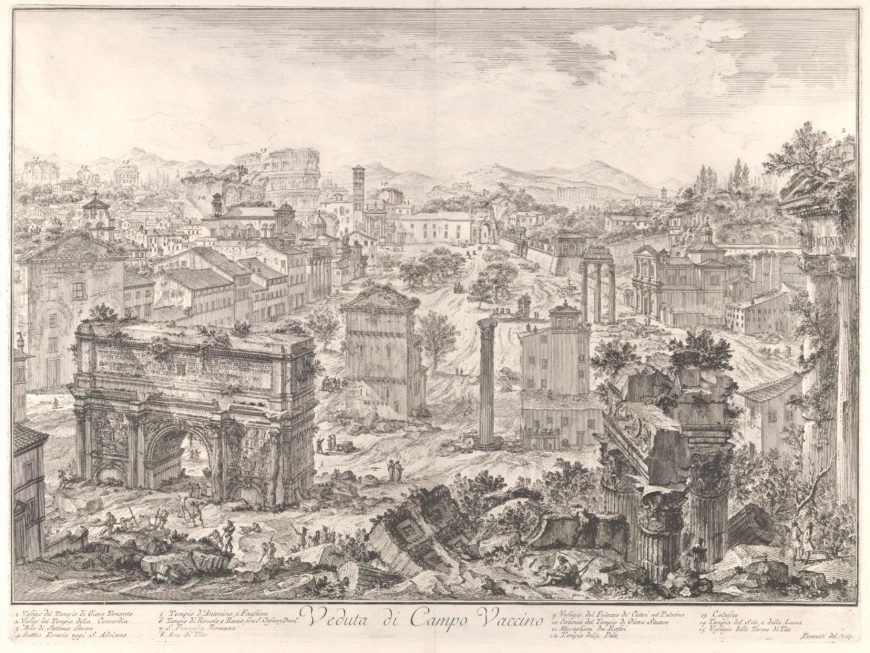

A ninth century guide for Christian pilgrims in Rome (known as the Einsiedeln Itinerary) notes that the forum had decayed from its former glory. It is likely that, as a landscape of disuse and re-use, the forum had by that time morphed into a form that perhaps would be scarcely recognizable today. The central square came to be used as grazing land, earning it the nickname “Campo Vaccino” or “cow field” by the Middle Ages.

This broken landscape of abandoned and discarded structures and monuments evoked the past and provoked the fancy and imaginations of viewers. It appealed particularly to artists who were keen to craft a romantic vision of the broken pieces of the past set amid the contemporary world. This romantic movement produced a genre of art in various media in the eighteenth century that is often referred to as vedute or “views”.

Painters the likes of Giovanni Paolo Panini produced vedute of ancient and contemporary Rome alike, often enlivening his canvases with contemporary human figures and their activities. In these “views” one can appreciate the creation of an assemblage, one that juxtaposes ancient elements with contemporary elements and human figures. The work of Panini and his contemporaries creates a romantic view of the past without being concerned overly with objectivity.

In the same century the artist and engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi was also active. Piranesi’s approach to the ruins of Rome alters the course of the field, not only in terms of artistic representation but also in terms of how we approach the ruins of past civilizations. One part of his oeuvre focuses on renderings of the ruins of Rome set amidst contemporary activity. The fragments of the past are very much the focus—their massive and monumental scale cannot help but capture the viewer’s attention. Despite the expert draughting of Piranesi, the ruins—being incomplete—remain a topic worthy of inquiry, as something of them is unknown.

The work of Panini, Piranesi, and others in the eighteenth century shows us that views of Rome are not just flights of fancy or imagination, but rather they are connected to memory. Piranesi was influenced in his early years by mentors interested in the revival of the ancient city as well as by others (namely Giambattista Nolli), who aimed to record the ancient remains in fine-grained detail. Piranesi, then, brings an expertise born from the school of the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio that is combined with an enthusiasm for Rome as the locus classicus of “old meets new.” The curation of views of the ancient remains not only reinforced shared memories of a past time but, also reinforced memory in contemporary terms.

Depicting ruins as fragile yet once powerful monuments might suggest that lessons derived from the past might help one to avoid the collapse and decay that is of course inevitable. These depictions of Rome’s past, encoded with memory, are important to the artistic culture of the eighteenth century and foreshadow what the nineteenth century will bring.

A disciplinary revolution

The nineteenth century witnesses a number of changes that in some cases move the conversation away from subjective romanticism and toward a more methodological approach to science and natural science. The discipline of archaeology emerges from this movement and, as with any new undertaking, the discipline needed to sort itself out in order to embrace a set of practices and norms. Antiquarians abounded but archaeologists were relatively new, even though early pioneers like Flavio Biondo (15th century) likely numbers among the first archaeologists.

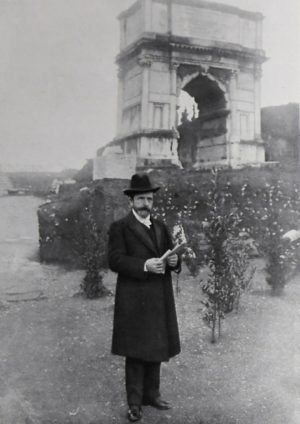

The nineteenth century was a momentous time for archaeology at Rome. The archaeologist Carlo Fea began an excavation in the Roman Forum to clear the area around the third century C.E. triumphal arch of the emperor Septimius Severus. Fea’s work ushers in a new era of what would become archaeological practice in the valley of the forum, as well as at other sites of the ancient city. Interest grew in decluttering or isolating the ancient moments. As the methods of archaeology developed, more scientific rigor could be observed.

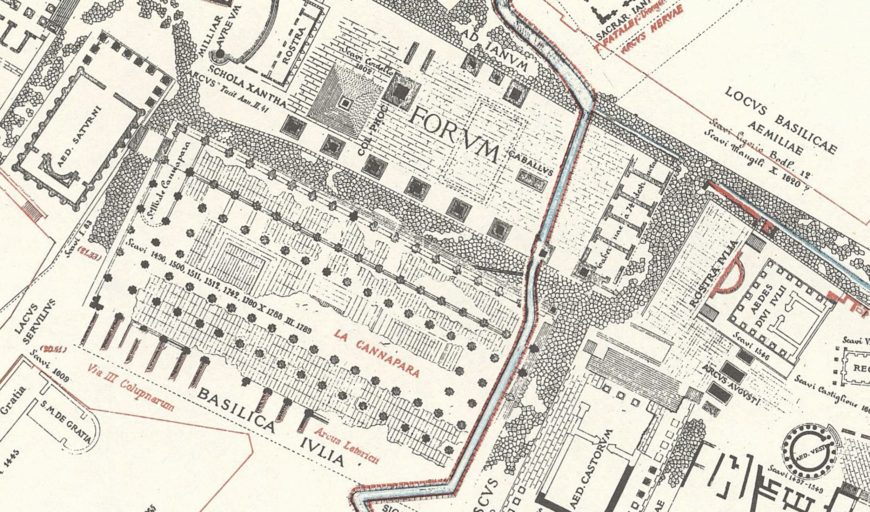

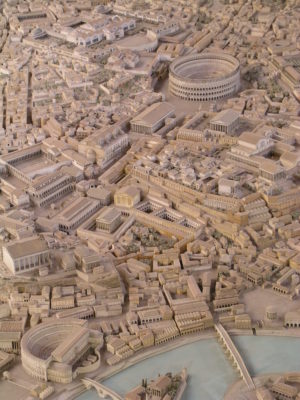

The Roman topographer Rodolfo Lanciani was a disciplined and active excavator at Rome. His magnum opus was the Forma Urbis Romae (1893–1901), a map at a scale of 1:1000 of the city of Rome, noting both ancient and modern features. It evoked earlier maps of Rome (for example the 1748 map produced by G. Nolli), but also reached back to the Severan marble plan of the third century C.E. in representing in detail the city and its monuments. One might see Lanciani’s Forma Urbis as a development that grew from the same tradition in which artists like Panini and Piranesi had worked—one could appreciate views of Rome, and, in so doing, gain a command of the sites and the memories linked to them.

At the turn of the twentieth century the excavations of Giacomo Boni in the Roman Forum were transformational, not only because they represented an enormous methodological advance for the time but also because they set the tone for archaeology in the forum thereafter. Boni’s stratigraphic excavations sampled previously unexplored layers of the city’s past and exposed the Roman Forum not just as a cow pasture with a few random columns protruding from the ground but as a complex cultural and chronological laboratory.

Some of the trends established in Boni’s time continued in the period of Italian Fascism (1922–1943) when archaeology showed a clear bias for the late Roman republican period and the principate of the emperor Augustus (31 B.C.E–14 C.E.). It was hoped that these earlier periods of perceived cultural, legal, and moral greatness would be examples that a modern Italian state could emulate. For this reason those archaeological strata were privileged, while others that were deemed unworthy were haphazardly destroyed in order to reach the preferred time period. In many ways these disciplinary choices were unfortunate and they do not find a place in twenty-first century archaeological practice. Nonetheless they shaped the landscape of the Forum valley that confronts us still day—one that is incomplete, at times chronologically incongruous, and evocative of an obviously complex past.

Contextual landscapes and fragments

Today the Roman Forum is part of a protected archaeological park that includes the Palatine Hill and the Colosseum. It is a site of significant popular interest and is visited by millions of tourists annually (7.6 million in 2018). It is also the site of ongoing archaeological research and conservation. The Forum is a challenging site to understand, both in terms of its chronological breadth and in terms of the processes of its formation (including archaeological excavation) that have shaped it.

The Forum should make us think about the goals of archaeology and the importance of archaeological context. One of the alluring things about the Forum is that it is fragmentary and incomplete. Latin authors were wont to mock the futile vanity of the potentates who sought to achieve immortality through the construction of monuments since those same monuments would inevitably decay. Their critique touches on a point that is central to a consideration of a fragmentary landscape like the Roman Forum, namely that the development of the space over time represents not just multiple time periods and historical actors but also multiple conversations between the space and the viewer.

The discipline of archaeology, in some respects, seeks to reassemble the past and it can only do this via contextual information. This means that the archaeological record needs to be preserved to the extent possible and then be interpreted in a rigorous and objective fashion. The impetus to reassemble what is broken informs our practice in many ways. It certainly influenced Lanciani’s plan of the city of Rome and Italo Gismondi’s model of the same. Scholars in the later twentieth and twenty-first centuries have similar motives, whether architect’s reconstruction drawings (see Gorski and Packer 2015), or a new archaeological atlas of the city inspired by Lanciani (see Carandini et al. 2012) or even 3D virtual renderings as in the case of the “Rome Reborn” project.

Our conversation with the Forum Romanum continues. In early 2020 there was a great deal of excitement about a re-discovery in the area of Giacomo Boni’s early twentieth century excavations. The site, perhaps connected with the cult of Rome’s traditional founder Romulus, provided an opportunity for a conversation that was both new and old at the same time.

Our views of the fragmented landscapes of the past are vital to our understanding not only of the humans who went before us but also, importantly, ourselves.

Additional Resources

ANSA news agency. “Hypogeum with sarcophagus found in Forum. Near Curia, dates back to sixth century BC.” February 19, 2020.

ArcheoSitarProject – SISTEMA INFORMATIVO TERRITORIALE ARCHEOLOGICO DI ROMA

Ferdinando Arisi, Gian Paolo Panini e i fasti della Roma del ’700 (Rome, 1986).

J. A. Becker, “Giacomo Boni,” in Springer Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by Claire Smith (Berlin, Springer, 2014). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1453

Mario Bevilacqua, Heather Hyde Minor, and Fabio Barry (eds.), The serpent and the stylus: essays on G.B. Piranesi, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome,

Supplementary volume 4, (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Published for the American Academy in Rome by the University of Michigan Press, 2007).

Mario Bevilacqua, “The Young Piranesi: the Itineraries of his Formation,” in Mario Bevilacqua, Heather Hyde Minor, and Fabio Barry (eds.), The serpent and the stylus: essays on G.B. Piranesi, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Supplementary volume 4, (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Published for the American Academy in Rome by the University of Michigan Press, 2007) pp. 13-53.

R. J. B. Bosworth, Whispering City: Rome and Its Histories (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).

Alessandra Capodiferro and Patrizia Fortini (eds.), Gli scavi di Giacomo Boni al foro Romano, Documenti dall’Archivio Disegni della Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma I.1 (Planimetrie del Foro Romano, Gallerie Cesaree, Comizio, Niger Lapis, Pozzi repubblicani e medievali). (Documenti dall’archivio disegni della Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma 1). (Rome: Fondazione G. Boni-Flora Palatina, 2003).

Andrea Carandini et al. Atlante di Roma Antica 2 v. (Milan: Electa, 2012).

Filippo Coarelli, Il foro romano 3 v. (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1983-2020).

Digitales Forum Romanum (Humboldt University)

Catherine Edwards and Greg Woolf (eds.) Rome the Cosmopolis (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Don Fowler, “The ruin of time: monuments and survival at Rome,” in Roman constructions: readings in postmodern Latin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) pp. 193-217.

Gilbert J. Gorski and James Packer, The Roman Forum: a Reconstruction and Architectural Guide (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Rodolfo Lanciani, Forma Urbis Rome reprint ed. (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1990).

Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1929). Preface

Ronald T. Ridley, The Pope’s Archaeologist: the Life and Times of Carlo Fea (Rome: Quasar, 2000).

Luke Roman, “Martial and the City of Rome,” Journal of Roman Studies 100 (2010), pp. 88-117.

Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project

The Roman Forum: Part 1, Ruins in modern imagination

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Ruins in Modern Imagination: The Roman Forum (part 1), an ARCHES video speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Roman Forum: Part 2, Ruins in modern imagination (The Renaissance and after)

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Ruins in Modern Imagination: The Roman Forum (part 2), an ARCHES video speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Roman Forum: Part 3, Ruins in modern imagination

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Ruins in Modern Imagination: The Roman Forum (part 3, Enlightenment to World War II), an ARCHES video speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Rome’s layered history — the Castel Sant’Angelo

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris at the Castel Sant’Angelo (Mausoleum of Hadrian), 139 C.E., Rome

Looted and revered: The Rosetta Stone

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): A conversation with Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker in front of the Rosetta Stone, Egypt, Ptolemaic Period, 196 B.C.E., granodiorite, 112.3 x 28.4 x 75.7 cm (The British Museum)

Ruin as abattoir, the Colosseum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Before the fire: Notre Dame, Paris

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\)

The fire

The blaze that engulfed the Cathedral of Notre Dame on the small Island known as the Île de la Cité in Paris in April 2019 was a terrible tragedy. Though it may not give us much comfort to learn that the total or partial destruction of churches by fire was a fairly common occurrence in medieval Europe, it does provide some perspective. For example, a fire destroyed most of Chartres Cathedral in 1020 (and again in 1194), in the city of Reims, the cathedral was badly damaged in a fire in 1210, and at Beauvais, the cathedral was rebuilt after a fire in the 1180s. The list goes on and on.

During the medieval periods of the Romanesque and the Gothic (c. 1000-1400), church fires were less frequent than they had been previously due to the development of stone vaulting (which began to replace the timber ceilings commonly found in European churches). But even a stone vault, as we saw at Notre Dame in Paris, is itself protected by a timber roof (sometimes rising more than 50 feet above the stone vaulting and pitched to prevent the accumulation of rain and snow), and this is what caught fire.

Art historian Caroline Brazelius, who has worked on the building for years said, “between the vaults and the roof, there is a forest of timber” — old, dry, porous, and highly flammable timber. Still, photographs of the interior show at least some of the stone vaulting survived the recent fire. The builders of Notre Dame used Parisian limestone, but, as Brazelius notes “when it’s exposed to fire, stone is damaged. It doesn’t actually burn….It becomes friable. It chips, and it’s no longer structurally sound.”

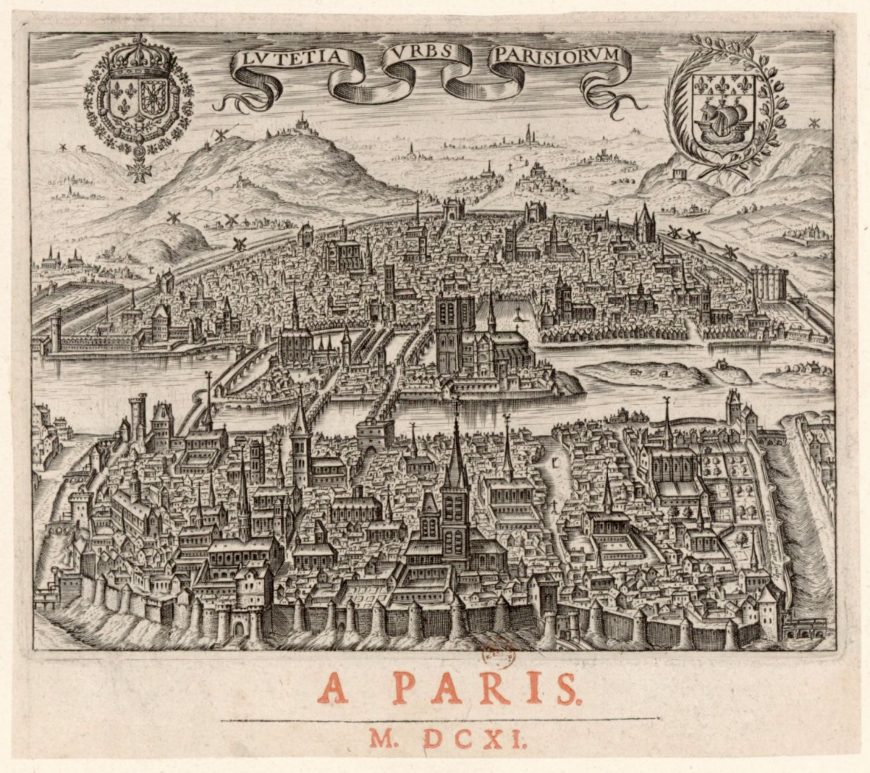

Built, modified, rebuilt, and restored

Churches are often an amalgamation of architectural styles, the result of building campaigns and modifications undertaken at different times, some due to fire, some due to the desire for what a new style represents, and some due to (often inaccurate) restoration efforts. And on a single site, churches were often built and rebuilt—and this is the case with Notre Dame in Paris. Before the Gothic-style church was built, a Carolingian church occupied the site (it was destroyed during the 9th century Viking invasions), and before that, a 6th century Merovingian Church stood on the site.

If we go back further, to the pre-Christian era, Julius Caesar’s armies famously conquered much of what we call France today (Roman Paris dates back to 52 B.C.E.). Archaeological evidence suggests that a pagan temple and then a Christian basilica were built on this site. The ancient Romans also built a palace for the emperor on the Île de la Cité, and after the Roman empire collapsed, Clovis I, King of the Franks (who converted to Christianity) established his palace there as well. The Île de la Cité would remain the location of a royal residence until the 14th century. As one historian has noted, “Notre Dame…was not only a religious but also a royal monument that displayed the might of the church and the monarchy, each enhancing the power of the other.” [1]

The Gothic Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris took nearly 100 years to complete (c. 1163-1250) and modifications, restorations, and renovations continued for centuries after. The early Gothic style employed at the beginning of the campaign became outdated and the later Gothic style, the Rayonnant, became fashionable and can be seen in the transepts. The crossing spire that the world watched fall while engulfed in flames was a reproduction created during a 19th-century restoration campaign.

In the following centuries, the church (and its sculptural decoration) survived multiple episodes of intentional destruction: during the Protestant Reformation (due to Protestant objection to religious imagery), and during the revolutions of 1789 and 1830 (because of the church’s close association with the monarchy). It remained in a neglected state until Victor Hugo’s novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) revived popular interest the building.

As of this writing, just a few days after the April 15th blaze, evaluation of the damage caused by the fire is only just beginning, but a reported one billion dollars has been already been raised to support the reconstruction of Notre Dame de Paris.

1. Avner Ben-Amos, “Monuments and Memory in French Nationalism.” History and Memory, vol. 5, no. 2, 1993, pp. 50–81.

Additional resources

The Cathedral’s construction (official website of Notre Dame de Paris)

Avner Ben-Amos, “Monuments and Memory in French Nationalism,” History and Memory, vol. 5, no. 2 (1993), pp. 50–81.

Caroline Bruzelius, “The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 69, no. 4 (1987), pp. 540–569.

Stephen Murray, “Notre-Dame of Paris and the Anticipation of Gothic.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 80, no. 2 (1998), pp. 229–253.

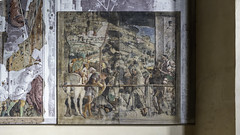

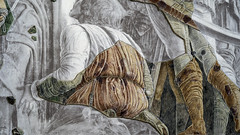

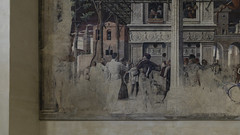

Reconstructing a masterpiece — Mantegna’s St. James Led to his Execution

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Mantegna, St. James Led to his Execution and the Ovetari Chapel cycle frescoes, 1447–58, Church of the Eremitani (Padua, Italy) reconstructed with photographs, original fragments, and inpainting after American bombs hit the church on March 11, 1944, an ARCHES video

A conversation with Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker in the Ovetari Chapel

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: