12.2: Whose art? Museums and repatriation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147869

Repatriating artworks

Repatriation is the return of stolen or looted cultural materials to their countries of origin. Although a belief that looting cultural heritage is wrong and stolen objects should be returned to their rightful owner dates to the Roman Republic (see Cicero’s Verrines) it was not until the 1950s, when the stark truths of colonization and war crimes against humanity began to be exposed, that a broad desire for restitution emerged and laws and treaties to facilitate this increased in number. Repatriation claims are based on law but, more importantly, represent a fervent desire to right a wrong—a kind of restorative justice—which also requires an admission of guilt and capitulation. This is what makes repatriations difficult: nations and institutions seldom concede that they were wrong.

The debate and law

The repatriation of art and cultural objects is a popular topic in the news and there is a familiar list of arguments on either side of the debate. The primary arguments for repatriation, most frequently deployed by countries and peoples who want their objects back, are:

- It is morally correct, and reflects basic property laws, that stolen or looted property should be returned to its rightful owner.

- Cultural objects belong together with the cultures that created them; these objects are a crucial part of contemporary cultural and political identity.

- To not return objects stolen under colonialist regimes is to perpetuate colonialist ideologies that perceived colonized peoples as inherently inferior (and often “primitive” in some way).

- Museums with international collections, often called universal or encyclopedic museums, are located in the Global North: France, England, Germany, the US, places which are expensive to visit and therefore not somewhere most of the world can go to see art. It is precisely a colonial legacy that allowed so many “universal” museums to acquire the range of objects in their collection.

- Even if objects were originally acquired legally, our attitudes about the ownership of cultural property have changed and collections should reflect these contemporary attitudes.

The arguments against repatriation, most frequently deployed by museums and collections which hold objects they don’t want to lose, are:

- If all museums returned objects to their countries of origin, a lot of museums would be nearly empty.

- Source countries do not have adequate facilities or personnel (because of poverty and/or armed conflict) to receive repatriated materials so objects are safer where they are now.

- Universal museums enable a lot of art from a lot of different places to be seen by a lot of people easily. This reflects our modern globalist or cosmopolitan outlook.

- The ancient or historical kingdoms from which many objects originally came no longer exist or are spread across many contemporary national borders, such as those of the ancient Roman empire. Therefore, it’s not clear to where exactly objects should be repatriated.

- Returning cultural objects which were obtained under colonial regimes to their countries of origin does not make up for the destruction of colonialism.

- Most objects in museums and collections, at the time of their acquisition, were legally obtained and therefore have no reason to be repatriated.

The debate over repatriation engages powerful and personal sentiments of morality, nationhood, and identity, and few people can talk about it without raising their voice. Regardless of this passion, however, the issue, ultimately, is a legal one and the international legal frameworks developed in the 20th century are what bring about repatriations. The first, which recognized the damage of warfare to property, was the 1907 Hague Convention, which forbade plundering of any kind during armed conflict, although it did not deal specifically with cultural property. The 1954 Hague Convention, however, in the wake of the widespread destruction of art during the Second World War, sought to expressly protect cultural property during armed conflict. The 1970 UNESCO Convention allowed for stolen objects to be seized if there was proof of ownership, followed by the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects, which calls for the return of illegally excavated and exported cultural property. Without these conventions and treaties, there would be no legal obligation for the return of anything.

Claims of repatriations

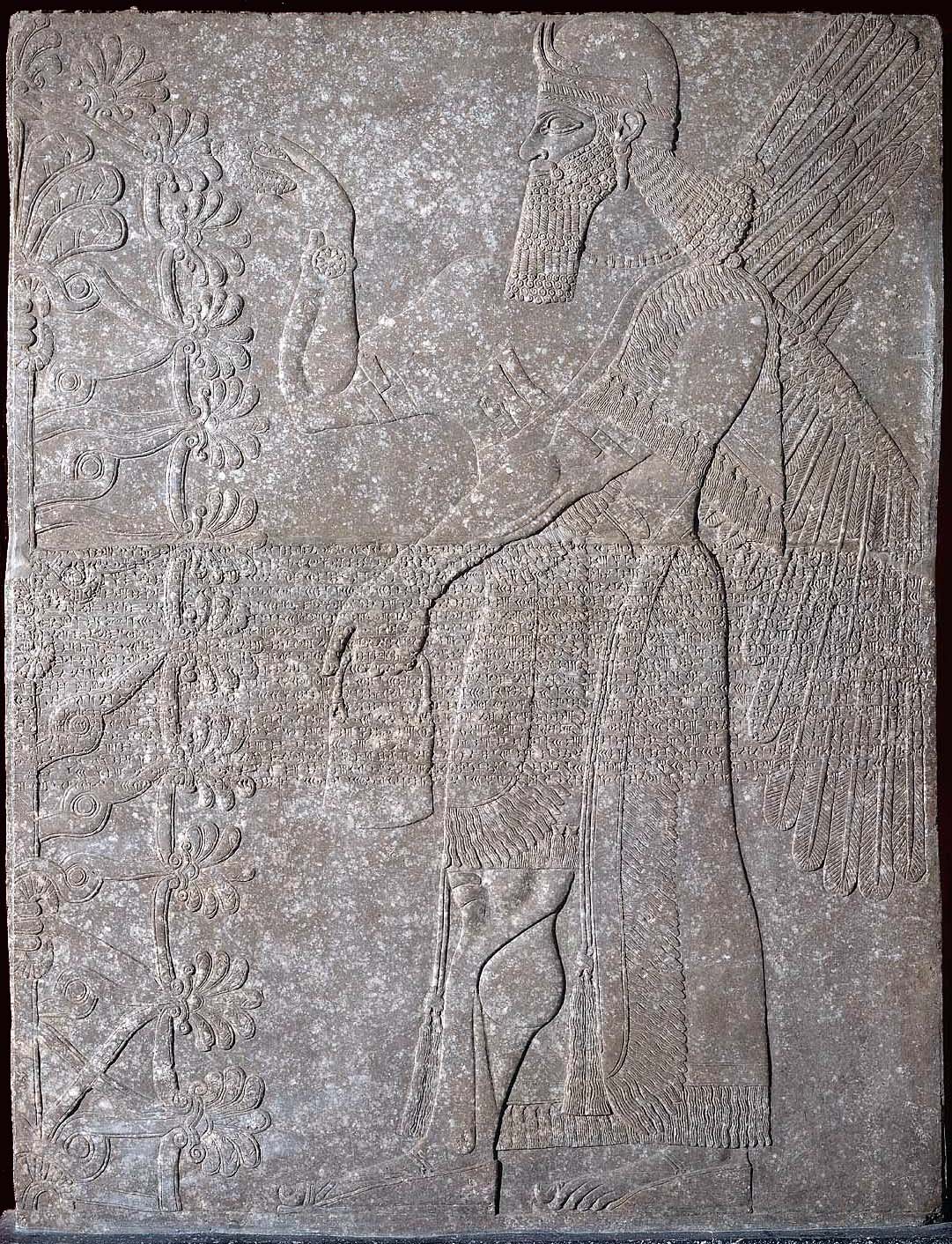

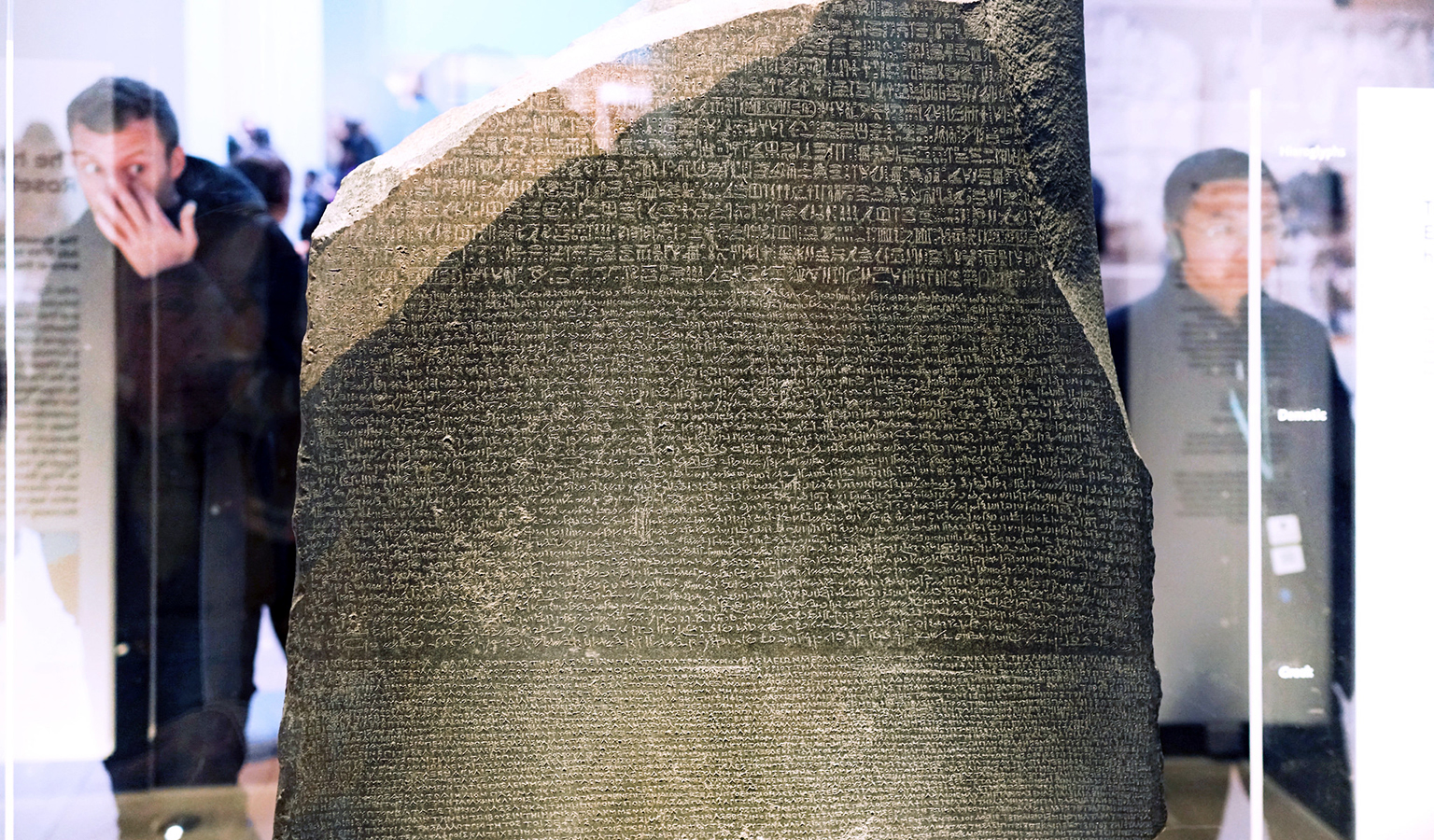

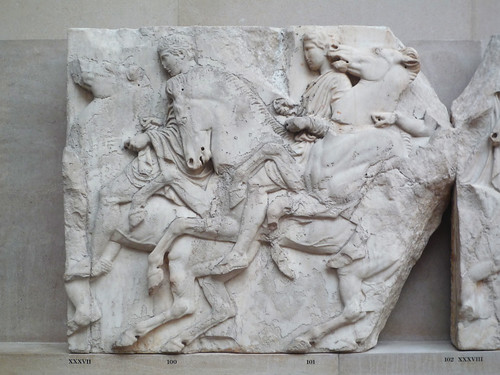

The vast majority of repatriation cases derive from colonial or imperial subjugation. Throughout history, across the globe, powerful nations and empires have taken valuable objects, including cultural property, from those they have conquered and colonized. These objects of beauty and esteem number in the many millions and most will likely be lost to their former owners forever. However, the theft of a few especially valuable and/or important objects have proven unforgettable and the subject of frequent repatriation requests. Examples are, for instance: the Koh-i-noor diamond, seized by the British East India company in 1849 and currently part of the British crown jewels; the Benin Bronzes, looted from the capital of Benin (in modern Nigeria) by British soldiers in 1897 and now spread across several museums in Europe and America; the Rosetta Stone, seized by British troops from the French army in Egypt in 1801 and today one of the most popular exhibits in the British Museum in London. The Parthenon Sculptures are another example.

Repatriation cases such as these have been approached, by and large, on a case-by-case basis, between the nations seeking return and the nations (and sometimes specific institutions), which hold these objects. More recently, however, as pressure for repatriations has increased, some former colonial powers are taking stock of their collections and moving towards large-scale repatriations. For instance, in 2017 France commissioned a report which recommended the repatriation of objects in French museums acquired during France’s colonial occupation of parts of western Africa.

In 2019, the German government passed a resolution to lay the groundwork to establish conditions for the repatriation of human remains and objects from German public collections derived from colonial rule. In 2019, The Netherlands’ National Museum of World Cultures pledged to proactively return all artifacts within its collection identified as stolen during the colonial era. These efforts, importantly, include sharing catalogues of holdings, a gesture of transparency which will greatly facilitate claims. However, as many point out, the stated intentions for large-scale repatriations are proving very, very slow to come to fruition and, moreover, several important museums (many in the United Kingdom) are conspicuous in their absence from the conversation.

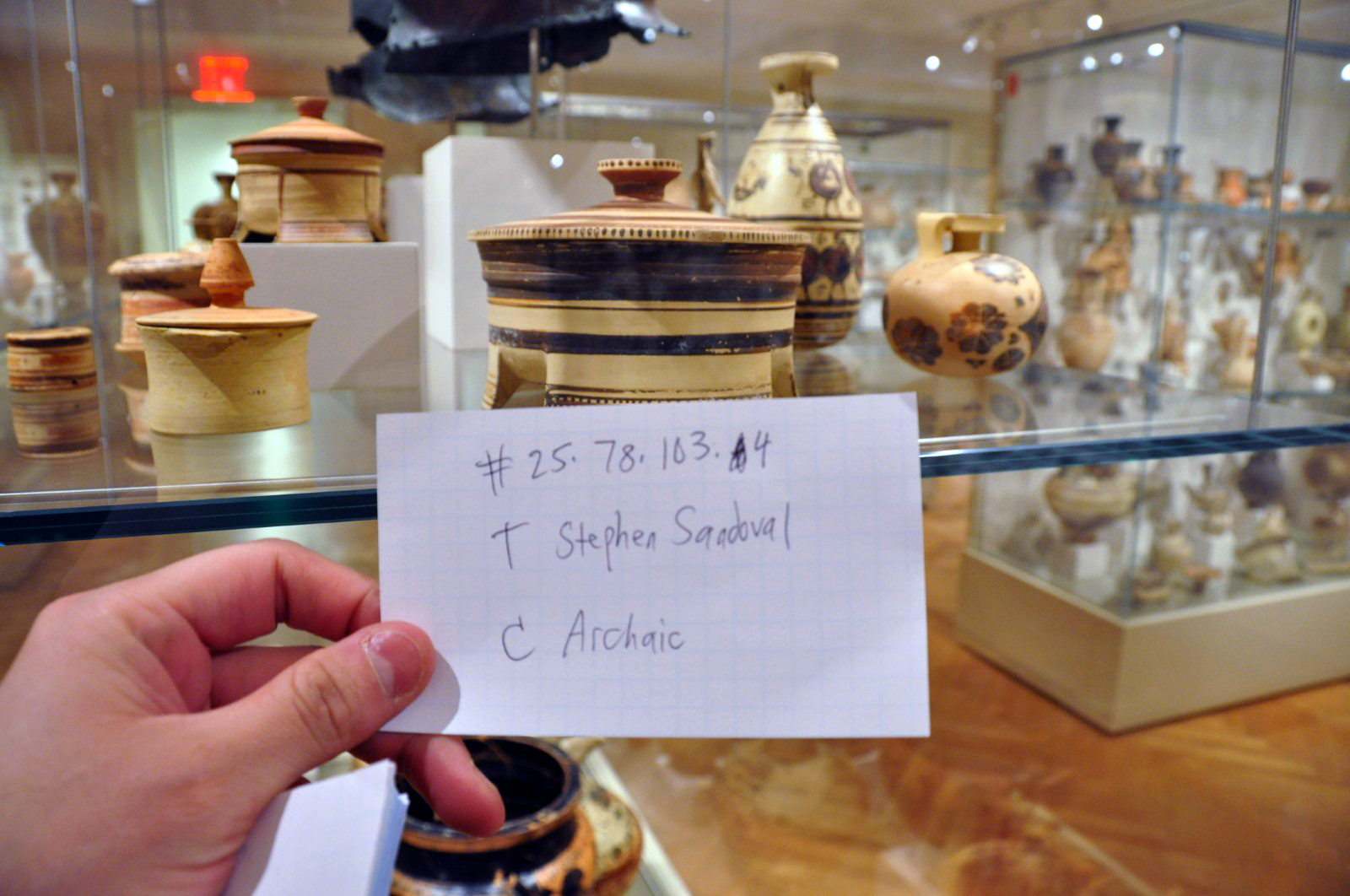

Colonialist desires to collect beautiful objects from far flung, exotic sources are still with us and because of this, wealthy individuals and institutions continue to collect cultural objects, ancient and contemporary. To meet this demand, modern looters (people who illegally dig up and steal cultural property) feed an underground market of antiquities and ethnographic objects. Often this looting is in conjunction with war or armed political conflict.

Repatriation claims for objects involved in this illegal trade of cultural property are especially difficult as proof must be established of the illicit extraction of the objects and thieves seldom document their work, especially in war zones. Moreover, these types of repatriation requests symbolize fresh colonial wounds, illustrating that the collection practices of the wealthy and powerful continue and less powerful nations and people are still vulnerable.

The good news is that successful repatriations of recent looting have occurred and those who purchase from the illicit trade are increasingly discouraged from doing so. For instance, in 2011, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston returned a Roman sculpture of Herakles to Turkey from which it had been stolen. In 2018 The National Gallery of Australia returned to India a bronze statue of the god Shiva which had been looted from a Hindu temple in Tamil Nadu. In 2020 The Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. returned nearly 11,500 looted objects to Iraq and Egypt, including approximately 5,000 papyri fragments and 6,500 clay tablets.

Another type of repatriation request is for the return of cultural objects and burial remains stolen from Indigenous populations by European invaders, largely in North and South America, Australia, Oceania, and New Zealand. What distinguishes these claims is the enduring living memory, among contemporary tribal communities, of specific objects and sites which were looted and desecrated and the acute spiritual need for their return and restoration. Indeed, these fragments of living culture can only be fully understood, properly used, and rightly treasured by their native owners.

In an attempt to address these sorts of repatriation requests, two legislated responses, the Native American Graves and Protection Repatriation Act (in the US,) and the Indigenous Repatriation Program (in Australia) were enacted. Through these two programs, legal frameworks for repatriation were established and hundreds of thousands of objects and human remains have been returned to Indigenous communities where they again work as powerful actors in the creation of spiritual, community and personal meaning. A famous example is the return of The Ancient One (also called Kennewick Man) after five Pacific Northwest tribes argued that the human remains were an ancestor. Still, the successful repatriation occurred only after genetic testing done by Danish scientists proved the Indigenous peoples’ claim, highlighting the ongoing colonialist legacies affecting cultural repatriation.

The era of repatriations has finally come. The work is slow and uneven and there are countless objects yet to return home, but repatriations are now occurring at a rate never before seen. What examples such as the Euphronios krater show us about repatriation is that objects come back changed. Not only physically but, because of the way they have been used (often ideologically) in their meanings as well — and, they cannot be changed back. Even if they are exhibited in quiet and historically proscribed ways (as in the case of the Euphronios krater), their life experience has made them bigger, louder, emotional, and more political.

When, for instance, the Parthenon marbles return to Athens they will never again only be the sculptural decorations of Athena’s 5th century B.C.E. temple. They have become so much more to Greeks, the English, generations of artists, historians, protectors of heritage, politicians, art law lawyers, and millions of visitors to the Acropolis and the British Museum. Through their dramatic biographies, we very much want to connect with, visit and understand repatriated objects and because of this they will not slip into obscurity in local museums, as is sometimes feared. The great power, the searing meaning that repatriated objects communicate, is that lost things can come home, that a wrong can be righted, and that we can all take part in that celebration and moral victory

Additional resources

Read more about how the seizure of looted antiquities often illuminates what museums want hidden

Read more about cultural heritage

Read about provenance and the antiquities market

From tomb to museum: the story of the Sarpedon Krater

by DR. ERIN THOMPSON and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Euphronios, Sarpedon Krater, (signed by Euxitheos as potter and Euphronios as painter), c. 515 B.C.E., red-figure terracotta, 55.1 cm diameter (National Museum Cerite, Cerveteri, Italy)

The many meanings of the Sarpedon Krater

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Euphronios Vase (or Sarpedon Krater), signed by Euxitheos as potter and Euphronios as painter, c. 515 B.C.E., red-figure terracotta, 55.1 cm diameter (National Museum Cerite, Cerveteri, Italy, photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art returns a pot to Italy

One of the most notorious repatriations is that of a 6th century B.C.E. ancient Greek pot, commonly referred to as the Sarpedon Krater or Euphronios vase. This pot was looted from an Etruscan tomb not far from Rome in 1971 and a year later illegally bought by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (MMA). The Italian government eventually requested the return of the pot, having collected evidence for its theft and illicit sale. In 2008, seeking to avoid a long and potentially damaging court battle, the MMA struck an agreement with the Italian government for its return. After it was exhibited at the National Etruscan Museum, the Villa Giulia, in Rome, in 2014 the vase was moved to The National Archaeological Museum of Cerveteri, nearby the Etruscan tomb from which it had been stolen 43 years before. Italy had achieved the impossible: forced the return of a stolen piece of its history from a wealthy and influential universal museum.

In the story of the repatriation of the Euphronios vase—this unequivocal win for the protection of heritage and redress of colonialist collection strategies—we have the opportunity to reflect on the various meanings and phenomena of repatriation: what gets lost, what gets gained, and how meanings shift.

With the Euphronios repatriation, the MMA gained an end to legal entanglements and perhaps some moral high ground for negotiating the return. Needless to say, however, it lost its very expensive and beautiful pot. But, what else was lost? Perhaps a bit of authority to write a certain type of history.

Museums are, among other things, in the business of codifying the history of art. Within institutions like the British Museum, the Vatican, and the MMA, the arrangements of their spectacular treasures have written the history of art for nearly three centuries. In this history, individual works are markers on a timeline: a painting, sculpture, or ancient pot. And this history has nearly always been presented as tidy, inevitable, and linear, with white Western men nearly always at the forefront of invention and innovation, as conquerors, kings, popes, explorers, pioneers, collectors, patrons, painters, and sculptors. In short, a white male imperialist history. Therefore, the great pieces of art in universal museums are not only valued for their beauty or cultural worth but also for their role in the establishment of a particular imperialist art historical knowledge. With the return of the Euphronios vase, the MMA has lost, in some measure, its authority to do this.

As for Italy, what is gained by the return of the Euphronios vase is substantial. With the vase brought back to the region in Italy where it was buried in a tomb, The National Archaeological Museum of Cerveteri gains a star object, with which it can highlight first rate Greek vase painting and construct a more nuanced and contextual meaning of ancient Etruscan burial and culture in the region. And, of course, Italy has won a notorious repatriation fight against a formidable opponent, which gives hope to others with similar repatriation claims.

The social life of the Euphronios vase

And what about the vase itself? Although it sounds odd, thinking about the experience of the Euphronios vase reveals a lot. Anthropologists and art historians like to think about the social life of things, or the biography of objects. This approach ascribes the meaning of an object not through its maker or owner but rather by a study of its form, use, and trajectory—its life history. So, how has the form, use, and long travels of the Euphronios vase made its meaning?

The Euphronios vase began its life at about 515 B.C.E., born in the Keramikos, or potters’ quarter, just outside the walls of ancient Athens, made from Attic clay. The pot itself was formed by Euxitheos and painted by Euphronios, an innovative painter who would, in the modern era, come to be regarded as one of the most talented Greek pot painters. The Euphronios vase was not cheap; scholars surmise it would have cost approximately a week’s wages in the 6th century B.C.E. The vase, in shape, is called a krater—a large wine serving bowl—intended to be the focal point and inspiration of discussion, at an all-male drinking party called a symposium.

The pot has painted scenes on two sides, the most remarkable of which illustrates a moment from Homer’s Iliad, recounting an episode in the Trojan War between the Achaeans (Greeks) against the city of Troy (which was also largely Greek). On the vase we see a slain warrior on the Trojan side, Sarpedon carried off the battlefield by the gods of sleep and night, to be returned to his homeland for proper burial. Sarpedon was killed by Patroclus, who is then killed by Hector (prince of Troy), an event which leads to his death at the hands of the famous warrior Achilles (but not before Hector prophesizes Achilles’s death). An Athenian would have known the dark prophecy of the death of Sarpedon, and no doubt such an image would have inspired drinkers to reflect on a range of topics, such as the inevitability of death, the imperfect power of the gods, the fate of great warriors, and the primacy of burial rituals. The very material of the pot, the story it tells in its decoration, and the symposium for which it was made all reflect a deeply Hellenic identity. Despite this, the Euphronios vase eventually left its homeland forever.

Indeed, it is unclear how long the pot remained in Greece but at some point, it traveled across the central Mediterranean Sea to Etruria (the land of the Etruscans, the central area of Italy, around Rome). Thousands of Athenian pots were sold to the Etruscans from the 8th to the 3rd century B.C.E. and thousands were placed in Etruscan tombs so we can safely assume that they were desired and valued by their buyers—although not much is known about how they were used. We assume that Etruscans used them in the ways the Greeks used them, wine cups for drinking, hydria for serving water, and kraters (like the Euphronios vase) to mix wine and water together, likely on a special occasion, given their value. However, there is evidence from painted tombs that Etruscan women participated in feasts in which Greek pots were used, which is different from Greek practice. How deeply the Etruscans understood the Greek identity is hard to know. How long the Euphronios vase was used by its Etruscan owner(s) is also hard to say.

The tomb in Cerveteri, in the Greppe Sant’Angelo necropolis, where the Euphronios vase was entombed, was huge, with many chambers, and used from the late 4th to 3rd century B.C.E. Because the tomb was looted and we have no associated finds to date nor the exact part of the tomb in which the pot was found, we cannot date its burial any better than the date of the tomb itself. But, this alone tells us that the Euphronios vase was used for at least a century before it was buried; sadly, we don’t know if this use was mostly by Greeks or Etruscans because we don’t know when it arrived in Italy. However, a precise repair, with metal rivets, was made sometime in antiquity, which can be seen on the less famous side of the vase, which shows young men readying for battle. This reveals to us some vigorous use and special care.

The looting of the tomb

In December of 1971, the tomb in Greppe Sant’Angelo was looted and the Euphronios vase was stolen. If the vase was again broken during its theft is not known but we do know that when it was illegally exported to Switzerland it was extensively repaired. It was then sold to the MMA, for $1 million, the greatest price the museum had ever paid for a work of art. The pot was conserved again by the MMA upon its arrival in New York (to which it travelled in its own first-class seat on a TWA flight from Zurich) and treated to a bespoke glass case, designed by staff from Tiffany’s, at its unveiling. The pot’s initial display at the MMA was a great media event. It was described as the finest Greek pot to survive from antiquity; the director of the museum at the time called it an ancient Leonardo da Vinci. The vase was immediately featured in books about ancient Greek art and general survey texts, picked out as a singular achievement in the narrative of Western art history. With the Euphronios vase’s installation in the Greek and Roman galleries of the MMA its previous life as an object of Etruscan value was erased. The Euphronios vase became one of the many focal points of the museum’s collection, arguing for a narrative that places the singular achievement of ancient Greek art at the foundation of Western visual heritage, where it became the wellspring of the Renaissance and Enlightenment, and an expression of Western imperialist inevitability and dominance.

In its New York home, the Euphronios vase was enjoyed by increasing numbers of visitors from the 1970s on to the first decade of the 21st century; the MMA had over 4.5 million visitors in 2007, the last year of its stay. In addition to these public viewers, the Euphronios vase hosted scores of academic and celebrity visitors, not to mention regular after-hours attention from conservators, lighting technicians, photographers, security consultants, exhibition designers, and curators, seeking to extract from it maximum historical and aesthetic content. The Euphronios vase lived in the MMA as a subject of near constant focus, awe, and inspiration.

The attention which the Euphronios vase enjoyed in its temporary New York residence can hardly compare with the emotional hero’s welcome it received at its homecoming to Rome, in 2008. Its first unveiling occurred at the Presidential Palazzo del Quirinale, in a special exhibition together with other repatriated objects entitled Nostoi, which means “those who return home,” also the title of a lost ancient Greek epic poem, about the return of the Greek heroes after the sack of Troy.

The Nostoi exhibit was widely covered by the international press, its reviews full of pathos and emotional satisfaction, also seen as an example of Italian political savvy on the part of the increasingly unstable government of president Romano Prodi. At the Palazzo del Quirinale, the Euphronios vase wasn’t standing in for the superiority of Greek art or the foundations of Western heritage in an imperialist narrative; it spoke instead of the return of a precious object to its homeland after a long struggle far away, a triumphant warrior of a watershed battle in the growing cause for cultural heritage repatriation. Remember the vase was made in Greece, though it was found buried in an Etruscan tomb in central Italy.

The next move for the Euphronios vase was to the National Etruscan Museum at Rome in the Villa Giulia, where it was exhibited, for the first time, as a treasured piece of Etruscan culture. Its meaning now shifted yet again, to one centered around Etruscan appropriation of Greek sympotic practice, trade with the wider Mediterranean world, and burial customs. Visitors to the Villa Guilia came to learn about the pre-Roman history of Italy, to understand one of the earliest civilizations of the Italic peninsula (the Etruscans), a part of which was the trade in beautiful Greek vases. The Euphronios vase now told a story anchored in its own ancient Italic experience, not about the foundations of Western art and imperialism in a universal museum, not the catharsis of a long sought and hard-won repatriation, but the story of its past owners and users.

Returning home

And, finally, in 2014, the Euphronios vase was installed in a museum very close to where it had been deposited in antiquity, The National Archaeological Museum of Cerveteri, a 15-minute drive from the Greppe Sant’Angelo necropolis (in what was once Etruria, the home of the Etruscans). It now sits among other grave goods and assemblages found in local Etruscan tombs, excavated by archaeologists who work to reveal and understand Etruscan culture. The Euphronios vase is now truly home, back in the region where in antiquity it had been cherished as an elite Greek import, regarded with wonder in lively social ceremony, and chosen to accompany its owner into the afterlife and eternity.

The Cerveteri museum is a quiet place, especially on the second floor where the Euphronios vase is exhibited, and it is easily missed by less intrepid museum visitors. And those visitors are a tiny fraction of those the pot has been accustomed to seeing: the Cerveteri museum welcomed some 12,500 visitors, in 2018. But, for those who climb the steps to find the Euphronios vase in the cool solitude of its new museum home, they will find not only a remarkable ancient object but a nearly impossible challenge: to believe that this is the pot which has traveled so far away and returned, suffered destruction and careful restoration twice, been the subject of so much violence, desire, admiration, and contention, whose meaning has been remade so many times: Attic Greek, Etruscan, Greek again but in the service of a Western imperialist narrative, glorious booty returned to its Italian homeland, a poster child for repatriation battles, then Etruscan again, in a deeply local and contextual way. This quiet wonder can be contrasted with the continued high celebrity which the Euphronios vase enjoys on the global digital sphere. Indeed, because of its complex biography, it is among the most famous pots in the world.

Additional resources

Read about the Euphronios krater on Trafficking Culture

Elizabeth Marlowe, Shaky Ground: Connoisseurship and the History of Roman Art (London: Bloomsbury, 2013)

Nigel Spivey, The Sarpedon Krater: The Life and Afterlife of a Greek Vase (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019)

Who owns the Parthenon sculptures?

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Also watch Smarthistory’s videos on The Parthenon and it’s sculptures

Additional resources:

How the Parthenon lost its Marbles (National Geographic)

The British Museum on the Parthenon sculptures

William St Clair, Imperialism, Art & Restitution: The Parthenon and the Elgin Marbles

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Plunder, war, Napoleon and the Horses of San Marco

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Horses of San Marco (ancient Greek or Roman, likely Imperial Rome), 4th century B.C.E. to 4th century C.E., copper alloy, 235 x 250 cm each (Basilica of San Marco, Venice), an ARCHES video

Additional resources:

Patricia Mainardi, “Assuring the Empire of the Future: The 1798 Fête de la Liberté,” Art Journal, vol. 48 (2014), pp. 155-163

Paikea at the American Museum of Natural History

During the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, the trade in ethnic artifacts was rife, particularly where territories had been colonized by European powers. Thousands of artifacts of all descriptions from across the Pacific were traded legally and illegally, and many now reside in museums, private collections, and other institutions throughout the world—including an important sculpture of a Māori ancestor named Paikea (pronounced pie-kee-ah)

The Whale Rider

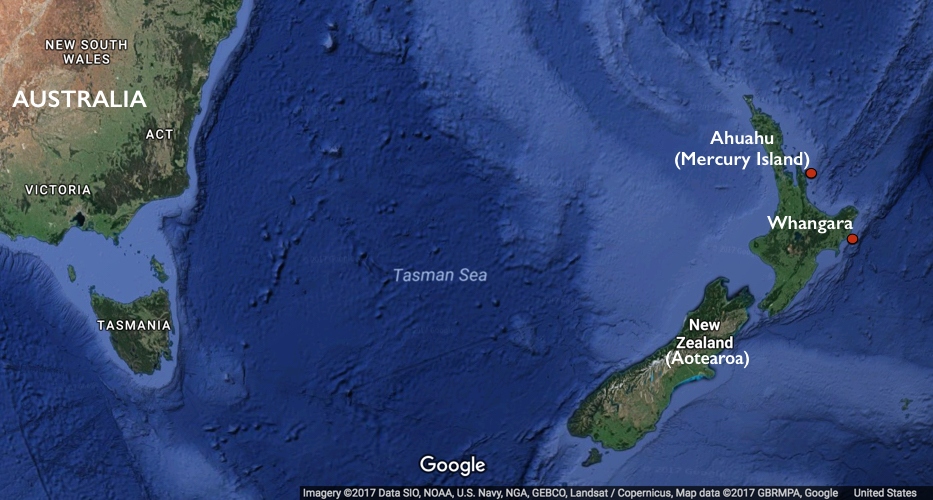

Paikea was an important ancestor of the Māori tribes in Uawa (Tolaga Bay) on the East Coast of the North Island of Aotearoa (New Zealand). He survived a marine disaster in the ancient Hawaiki homeland of the Māori in the Pacific Ocean, by invoking, through incantation, the denizens of the deep sea to come to his rescue and take him ashore. Paikea eventually made landfall at Ahuahu (Mercury Island) in Aotearoa (New Zealand). After several excursions to the south-east, Paikea eventually made his way to the mouth of the Waiapu River on the East Coast, married Huturangi, and settled at Whangara. He is more popularly known throughout the world as “The Whale Rider,” from the movie of the same name.

For his many descendants, Paikea is a key link to the ancient Hawaiki homeland, as well as to the marine stories and body of seafaring knowledge, and to the tribal settlements on the eastern seaboard of both islands of Aotearoa (New Zealand). He is honored through songs, genealogy, stories, dances, novels, film, and art.

A house and a dance

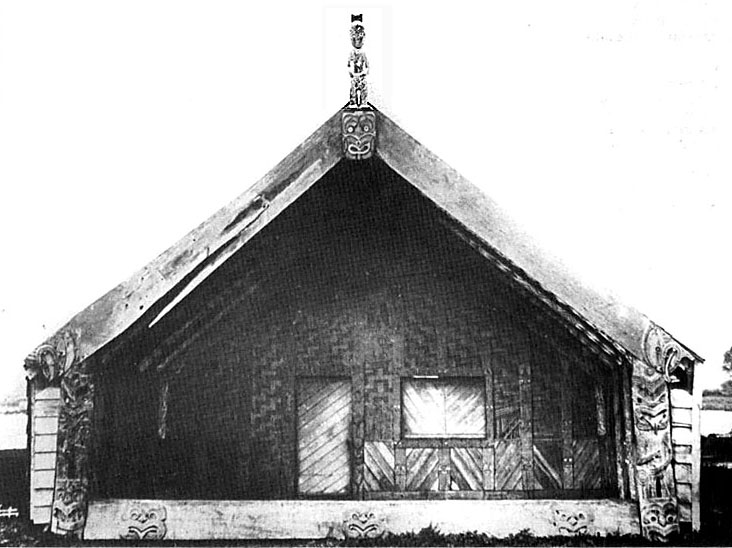

Paikea’s descedant, Te Kani a Takirau, was born 23 generations later, in about 1790. He was regarded throughout Māoridom as a leading ariki, a noble high-ranking person of his time. After Te Kani a Takirau’s death in 1856, a carved house was built by his people at Uawa, and named after him (see photograph at the top of the page). The carved figure on top was named Paikea, and notable orators composed a haka (posture dance) for this occasion:

| Uia mai koia whakahuatia ake | If it is asked |

| Ko wai te whare nei e? | What is the name of this house? |

| Ko Te Kani | It is Te Kani |

| Ko wai te tekoteko kei runga? | Who is the figurehead on top? |

| Ko Paikea, ko Paikea | It is Paikea, it is Paikea |

| Whakakau Paikea | Paikea transformed |

| Whakakau he tipua | Into an amazing being |

| Whakakau he taniwha | Into an awesome being |

| Ka ū Paikea ki Ahuahu, pakia! | And Paikea did come ashore at Ahuahu! |

| Kei te whitia koe ko Kahutiaterangi | Do not mistake him for Kahutiaterangi |

| E ai tō ure ki te tamahine a Te Whironui | He cohabited with the daughter of Te Whironui |

| Nāna i noho Te Rototahe | And resided at Te Rototahe |

| Auē, auē he koruru koe, e koro e! | You are there sire as the figurehead! |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Since that time, six generations of Paikea’s descendants have performed this haka. For the past four generations it has also been performed as a waiata ā-ringa, an action song. In the last two generations it has developed into a novel—The Whale Rider, by Witi Ihimaera—which became the basis for the movie of the same name. This legacy now centers on another house: Whitireia at Whangara, on top of which Paikea sits on his whale. Children who are born into the legacy of Paikea “absorb” the haka and the waiata ā-ringa while growing up, performing it with peers, parents, and grandparents. It is a tribal marker, a rallying call, an expression of pride, and a reminder of our origins.

A century in storage

In 1908, the American Museum of Natural History acquired the Te Kani a Takirau Paikea from Major General Horatio Robley (British Army), a colonial collector of the time. Paikea was eventually placed on a storage shelf until 2013 when a small group of Paikea’s descendants of Te Aitanga a Hauiti, the tribe of Uawa, arranged a visit to the museum for the purpose of reconnecting with this ancestor figure—part of a bigger plan to reconstruct the house Te Kani a Takirau, physically or digitally.

It was an emotional visit: a mix of tearful reunion, immense pride and melancholy reflection. Coincidentally, the visit occurred at the same time as the Whales (Tohorā) exhibition at the museum, which allowed us to share our Paikea stories with members of the public, museum professionals, students, and others.

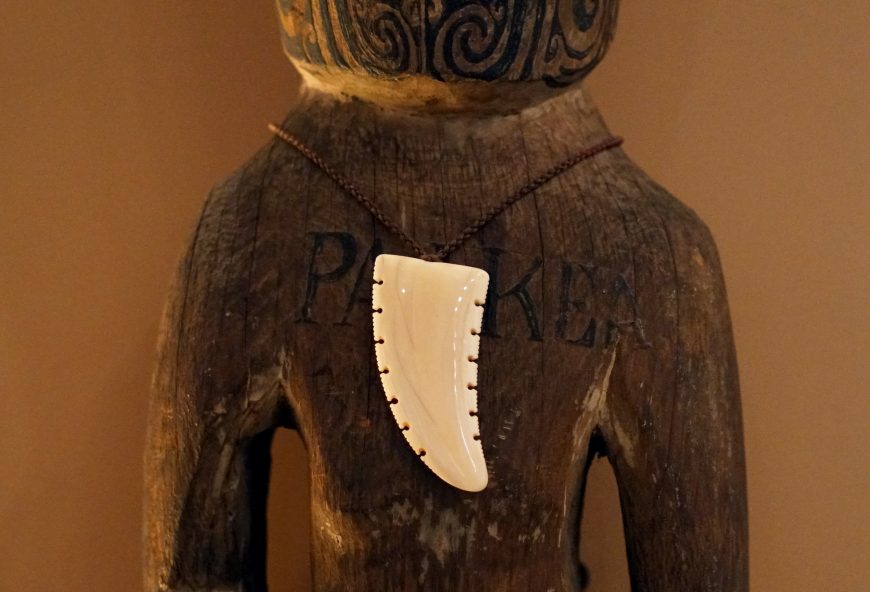

A token of love

Our parting with Paikea at the end of the week was difficult and tearful. As is our tradition, we left a gift with him as a token of our love: a carved whale tooth pendant sourced originally from a bull sperm whale that beached at Mahia in northern Hawkes Bay, New Zealand in 1967, which we secured around his neck. In doing so, we unknowingly transgressed museum acquisition protocols as well as international laws regarding trade in ivory, although we had done what was tika, or right, in our view. This provided an embarrassing conundrum for the museum curators who had hosted us, and so later that year the whale tooth was returned to us in New Zealand.

In 2017, as part of filming a documentary series “Artefact” and with the support of Greenstone TV, the American Museum of Natural History, and professional colleagues from Auckland University, we organized to return the whale tooth—legally this time—to Paikea, and make good our initial gift. Again, a small group of young people from Te Aitanga a Hauiti accompanied the whale tooth and once more the occasion, although shorter, was an emotional one. It was also an opportunity to consider repatriation again: both the process and the implications for the museum, and for Paikea’s descendants and their communities as well. This is what we will deliberate on over the next few months as we reflect on our experiences with this icon of our history and symbol of the colonial artifact trade.

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Additional resources:

Paikea at the American Museum of Natural History

Listen to a native speaker say “Maori”

Nazi looting: Egon Schiele’s Portrait of Wally

by DR. ERIN THOMPSON and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Egon Schiele, Portrait of Wally Neuzil, 1912, oil on panel, 32 × 39.8 cm (Leopold Museum, Vienna) Speakers: Dr. Erin Thompson and Dr. Beth Harris

Seizure of Looted Antiquities Illuminates What Museums Want Hidden

Over 20,000 precious art objects were seized in a raid at dawn — what can this tell us about beauty, theft, and the museum?

On July 4, 2018, Europol and the Italian Carabinieri’s Division for the Protection of Cultural Heritage announced the culmination of “Operation Demetra.” This criminal investigation, tracking a network of Sicilian archaeological looters and international traffickers, resulted in dawn raids on 40 houses in 4 countries and the arrest or detention of 23 people, and the seizure of some 20,000 plundered objects worth an estimated €40 million (approximately $46.6 million).

Art, photography, and unspoken messages

The Europol press release was accompanied by an uncaptioned photograph of a beautiful, naturalistic marble portrait head, presumably one of the works seized in the raids. The portrait depicts a young, beardless man wearing a veil over the back of his head. The figure has a protruding, dimpled chin, and very small ears, but there are few signs of individualization here.

On the basis of its similarity to other works, the portrait can be plausibly identified as a young man of the Roman imperial family from the early 1st century C.E. The sculptor was skilful at capturing in stone the appearance of soft, youthful skin as it stretches over cheekbones and puckers out at the corner of the mouth The nose and left cheek are damaged, but otherwise, the piece seems to be in extraordinarily fine condition. It would be a centerpiece in the ancient gallery of any museum in the world today.

The head has much in common with other Roman imperial portraits, but the Europol photograph is unique. The depiction is not at all how we’ve become accustomed to seeing ancient sculpture presented. Museum and art market photography usually features pieces like this against a seamless muslin backdrop. The backdrop can be black or gray or, for a little spice, it can fade from black to gray or from dark gray to light. The neutral color, the absence of a horizon line and of any representational detail other than the single object itself, work together to situate the piece in an other-worldly realm, one far removed from any actual specific, physical location. The non-space of these official photographs complements the museum rhetoric of universality. This rhetoric is grounded in a philosophy of art that goes back to Immanuel Kant.

Museums and contexts

Implicitly in their architecture and explicitly in their labels, art museums frame their holdings as manifestations of creativity, genius, truth, and beauty — ostensibly universal and timeless human values. This makes the objects’ installation in a museum, often far removed from the particular culture and setting for which they were created and where they may still hold very different meanings, seem unproblematic and even natural.

Sometimes the rhetoric of universality takes on a more literal and pragmatic meaning, as when self-proclaimed “universal museums” claim the right to own — and retain — objects from every corner of the globe, regardless of the dubious circumstances by which they may have acquired them. The two concepts of universality are, of course, mutually reinforcing; and the gray vacuum photographs of record are part and parcel of this ideological apparatus.

The Europol press release photo is the antithesis of the gray vacuum images. It is teeming with details that anchor the ancient portrait in a very particular and very mundane realm. The most startling of these details are the two slippers partially visible along the lower edge on either side of the head. These must be the slippered feet of the photographer himself, as he stood over the marble head and aimed his camera at the floor.

The head is lying on what looks like a nice Persian carpet, but our photographer was apparently untroubled by the disarray surrounding it: a pen, whose metal clip catches the light in the image’s upper left corner; two pieces of battered wooden furniture; what appears to be an ornate but broken gilded plaster picture frame; and a blue crocheted blanket. It would not have taken much to push all this detritus out of the frame of the photograph, but our cameraman did not bother. He also apparently couldn’t be bothered, before snapping the picture, to turn off his TV, the blue glow of which illuminates the portrait’s proper right side.

These details not only root the image in a specific earthly setting; they also introduce a concept art world insiders usually take pains to hide from the general public: the inevitably messy human agency behind the removal and relocation of artworks or cultural objects from their original context to their end destination in a gallery display. Europol didn’t release any information about the photograph itself, and it is possible that it was taken by one of the investigators. The slippered feet, however, suggest a different actor, someone in possession of the looted head in his own home.

Erasing stories, erasing the past

We know from other cases of looted antiquities that middlemen often photographed their wares after receiving them from the tombaroli (grave-robbers) who dug them out of the ground. The photographs were used to shop the pieces around to potential buyers. Perhaps this photograph was meant to serve as the basis for negotiations over price between the middleman and the dealer whose role in this network was to smuggle the pieces out of Italy to Munich, where, the investigators claim, they were supplied with false provenance papers and sold at auction. No doubt this laundering entailed new photography as well.

The Europol photograph is a stark reminder that many of those polished marble masterpieces on their spotlit museum pedestals were once merely raw goods on the floor of a crook’s cluttered living room. The alchemy is usually carefully hidden from view; museums do everything they can to keep our attention away from the men behind the curtain.

In its power to reveal more profound truths about museum objects, the Europol photograph recalls the famous image of those manspreading colonialists, the members of the British Punitive Expedition, seated atop their loot at Benin in 1897. That is the “before” image to be paired with the loot’s “after” images, both in photographs of record and in the beautiful modernist grid in the new Sainsbury African Galleries of the British Museum.

The fact that these “before” photographs still have the power to shock years, and even decades, after debates about “decolonizing the museum” have become widespread, and the looting of antiquities is widely recognized as a scourge, reveals how thoroughly we’ve been conditioned by museum rhetoric of beauty and universality. The truth is that the route to the gallery is often ugly, built on crime, brute force, and lies. When we catch a glimpse of that reality, we must not look away.

This essay first appeared in Hyperallergic (used by permission).

Additional resources:

Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini. The Medici Conspiracy: The Illicit Journey of Looted Antiquities – from Italy’s Tomb Raiders to the World’s Greatest Museums (New York: PublicAffairs, 2007).

Europol’s post about Operation Demetra

Read more about Operation Demetra at Artnet

More information about Operation Demetra from ARCA

Read about a campaign to return looted Benin bronzes to Nigeria at Artnet

Looting, collecting, and exhibiting: the Bubon bronzes

by DR. ELIZABETH MARLOWE and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video\(\PageIndex{6}\): Bronze statue of a nude male figure, Greek or Roman, Hellenistic or Imperial, c. 200 B.C.E. – c. 200 C.E. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Speakers: Dr. Elizabeth Marlowe and Dr. Steven Zucker ARCHES: At Risk Cultural Heritage Education Series

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Napoleon’s booty—Perugino’s (gorgeous) Decemviri Altarpiece

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris in front of Perugino, Madonna and Child with Sts Laurence, Louis of Toulouse, Ercolanus and Constance (Decemviri Altarpiece), 1495–96, tempera on wood, 193 x 165 cm (Vatican Museums)