12.1: A beginner's guide

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147868

ARCHES, an introduction

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Our cultural heritage defines our humanity. Cultural diversity, like biodiversity, plays a quantifiable and crucial part in the health of the human species. An attack on cultural heritage in one part of the world is an attack on us all—on all of humanity. But cultural diversity is under grave threat around the globe. This wanton vandalism and destruction is not collateral damage—it’s a part of a ruthless wave of cultural and ethnic cleansing inseparable from the persecution of the communities that created these cultural gems. It’s also part of a cycle of theft and profit that finances the activities of extremists and terrorists. Any loss of cultural heritage is a loss of our common memory. It imperils our ability to learn, to build experiences, and to apply the lessons of the past to the present and the future.

—Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations, 12 April 2016

Smarthistory + ARCHES (At-risk Cultural Heritage Education Series)

At Smarthistory, we feel strongly that an informed public is essential to ongoing efforts to protect cultural heritage. ARCHES, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, offers a mini-course on endangered heritage around the globe. Taken together, these short videos and essays (see the left navigation for all the content) can serve as a stand-alone unit, however ARCHES was also designed to help instructors integrate the subject of endangered cultural heritage into their existing curriculum. For example, a course that touches on Renaissance Venice will find the video, Saving Venice useful. In addition to the essays and videos, we’ve added 20 “backstories” to existing Smarthistory content. These offer information on how some frequently taught monuments are endangered (and in some cases, have been destroyed).

Culture “in crisis”?

ARCHES begins with a provocative question, is culture in crisis? This question, proposed by Dr. Stephennie Mulder and Dr. Debora Trein, reminds us that the term “crisis,” even in the wake of ISIS’ destructive activities in the Middle East, suggests that the problem is urgent—but temporary—when in reality, using this word to define present circumstance may “provide new opportunities for heritage destruction processes that were already happening and will continue happening after the ‘crisis’ is over.”

The continuous nature of the problem of endangered and destroyed cultural heritage, and the fact that it is not limited to far-away countries in political disarray, underscores the importance of educating students about historical examples (some ancient, and others as recent as Pennsylvania Station) and the legal frameworks that exist to protect important works and sites.

More than forty years ago, the art historian Albert Elsen connected the problem directly to the classroom,

In 1977, no more explosive issue confronts the art world than the protection of Art. Fair question is whether as teachers and scholars we are doing the best job of educating our students to be aware of, comprehend, and deal with the problems of art’s protection….We teach our students the engineering and iconography of a Gothic cathedrals, but not why they should be preserved.[1]

Smarthistory created ARCHES to begin to remedy this problem. The question of endangered cultural heritage is inherently an interdisciplinary one. For this reason, ARCHES includes essays from legal experts, archaeologists, art historians, and those working in not-for-profits who fight to preserve irreplaceable remnants of human history.

Looting and the loss of the archeological record

The work of the archaeologist is often central to the protection of cultural heritage. The availability of dynamite and bulldozers in the modern era has enabled widespread looting and the subsequent loss of site context, and has created a class of orphaned objects that now pervade the art market. Looting of archaeological sites is a worldwide problem that often occurs in poor countries where local populations have few other resources and in rich nations such as the United States where, for example, a civil war site, the Petersburg National Battlefield, was recently looted.

What is lost in these cases is not simply prized objects that vanish into private collections, but also the valuable information that is destroyed when the site’s sediments are disturbed and less salable materials destroyed. A video on the archaeological record examines just how much we can learn when a site is excavated with modern, scientific methods, and just how much knowledge of the human past is lost through looting (videos on a Hellenistic Turkish bronze sculpture, an ancient Cambodian temple and a site from the Sicán culture in Peru drive this point home).

An essay on a popular archaeological site in Greece, the Palace at Knossos, asks us to think about what happens to an archaeological site after the archaeologist’s work is completed and whether we should restore sites for tourists and others. We could ask a similar question about monuments destroyed during war — for example the site of Palmyra, where ancient temples and gates were destroyed by jihadists in 2015. Should these be digitally reconstructed? What is lost when we seek to erase modern acts of destruction?

The role of scholars

Ancient works of art are not only repositories for cultural identity and vehicles for spiritual transcendence, they also carry monetary value that makes them a target for those who live in poverty, for the middlemen and dealers looking to make a profit, and for collectors who long for an important object. In recent decades this dynamic has, at times, pitted the archaeologist, art historian, or cultural heritage organization, against local populations.

In the ancient African city of Djenné, archaeologists unearthed terracotta figures (many covered with mysterious welts) that became highly valued by collectors. This in turn caused widespread looting of sites (during a period of famine affecting the region) and the appearance on the market of hundreds of unprovenanced objects. Archaeologists and art historians are engaged in a debate about whether to research and publish on these objects, work that may inadvertently increase their market value, and thereby encourage more looting and the inevitable loss of archaeological information.

The role of museums

We are still living with the ramifications of centuries of colonial domination. Major museums, especially those in the West, hold treasures obtained through conquest, revolution, colonial occupation, and the advantages of great wealth. Further, art museums have traditionally emphasized the aesthetic qualities of the object, often presenting a prized object alone in an illuminated transparent box. This display strategy hides not only the object’s original use — in a masquerade in West Africa, in a Buddhist temple, or on a church altar — but also has the effect of secularizing what was once held as sacred. This tension between the secular values of the encyclopedic museum (those museums with global collections often obtained through colonial ventures or through the donation of unprovenanced objects) which seeks to understand humanity across time and place, and the potentially more nationalistic sentiments of people who were colonized, is regularly played out in debates between archaeologists, museum directors, curators, and local populations. The most famous case-in-point are the Parthenon sculptures, which were taken from the Acropolis in Athens by a British nobleman in the early 19th century.

This is, however, a complex discussion. In some cases, the cultures that created the objects no longer exist; in other instances, efforts to link objects to traditions that do endure have been criticized as too far-reaching. Some also argue that the values of commonality—of a shared universal heritage—are more important than national claims especially if they are made by governments sullied by political agendas. Clearly, this is not a debate for those looking for a well-defined moral high ground. If, on the other hand, we are looking for a forum in which to examine how we define identity, and upon what we can base reciprocal cultural respect, then cultural heritage offers enormous advantages.

The story of the Euphronios Krater is a case in point. The krater, a large ancient Greek punch bowl, was purchased by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and became one of their most celebrated objects, not only because of the pot’s recordbreaking price, but because of its exceptional painting. The krater is now in a small regional museum in Italy, having been returned after it was discovered that the vase was likely looted from an ancient Etruscan tomb north of Rome. Questions linger about The Metropolitan’s acquisition and its willingness to overlook gaps in the pot’s provenance.

Art in times of war

Since antiquity, works of art have suffered during times of war. In the late 18th and early 19th century, as Napoleon conquered much of Europe, his troops looted thousands of works of art and shipped the most prized examples to Paris for Napoleon’s museum (which would later become the Louvre Museum). Though many were returned, others remain in the collection of the Louvre to this day. Napoleon also suppressed churches and monasteries across the parts of Europe he conquered and as a result, works of art made to inspire religious devotion (altarpieces, reliquaries, etc.) entered the art market in vast numbers, and — due to the saturation of the market — many remained unsold, and were damaged over time in storerooms, or during transportation. Many of these works made their way into European and American museums. It’s important to remember that there are often fascinating stories behind how works of art made their way to museums—stories not often revealed by a museum label.

The twentieth century too, saw a period of unprecedented upheaval for works of art during World War II. After decades of work by heirs and lawyers, many works of art have been returned to the (usually Jewish) families from which they were illegally confiscated by the Nazis, but thousands remain in museum storerooms. Just recently the Louvre opened an exhibition of 100 works of art looted by the Nazis in the hope that the rightful heirs might come forward (more than 1700 works remain in the Louvre that were confiscated by the Nazis, and many museums have offices devoted to researching the provenance of works of art, and returning confiscated works to the rightful owners).

The lasting damage to art during times of war can not be overestimated. Just a few years ago, thousands of manuscripts were smuggled out of Timbuktu during a period of civil war, and thanks to the hard work of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (and other libraries), they are being digitized so that future generations can learn from them.

What we lose when we uproot works of art

The dislocation of works of art — whether due to colonial practices, looting, or wartime activities — raises the difficult question of where works of art belong. Do they belong in their place of origin, or do they belong in universal museums (like The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The British Museum, or the Louvre) where they can be seen in an international context by tens of millions of tourists and students?

We worry about how much is lost when work is removed from the places and people they were made for — not just lost knowledge about the work of art, but also, in many cases, the tremendous loss suffered by those whose art has made its way into Western museums (usually from indigenous source communities). The case of an image of Paikea, a Māori ancestor, that was acquired in 1908 by the American Museum of Natural History is a good example. Paikea was placed on a storage shelf until 2013 when a group of Paikea’s descendants visited the museum to reconnect with this ancestor figure.

It is important to remember that for cultures throughout history and across the globe, images are not inanimate and powerless, rather they maintain an intimate connection to what they represent — whether that is an ancestor, an image of a deity, or a loved one. In the West, we would do well to remember the power and efficacy of images.

Conclusion

ARCHES was created to raise public awareness. We hope you will use and share these resources. We all need to do our part and to remember that it is not only well-known sites that are endangered, but also countless lesser-known places and objects that need our protection.

[1] Albert Elsen, “Bomb the Church? What we don’t Tell our Students in Art 1,” Art Journal, vol. 37, No. 1 (Autumn, 1977), pp. 28.

ARCHES was made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavour.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this video do not necessarily express those of the National Endowment for the Humanities

Additional resources:

Cultural Property at Risk — Questions and Answers (UNESCO)

Central Registry for Looted Cultural Property 1933-1945 (Europe)

International Centre for Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property

SAFE: Saving Antiquities for Everyone

UNESCO illicit trafficking of cultural property

UNESCO’s list of world heritage in danger

What is cultural heritage?

We often hear about the importance of cultural heritage. But what is cultural heritage? And whose heritage is it? Whose national heritage, for example, does the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci belong to? Is it French or Italian?

First of all, let’s have a look at the meaning of the words. “Heritage” is a property, something that is inherited, passed down from previous generations. In the case of “cultural heritage,” the heritage doesn’t consist of money or property, but of culture, values and traditions. Cultural heritage implies a shared bond, our belonging to a community. It represents our history and our identity; our bond to the past, to our present, and the future.

Tangible and intangible cultural heritage

Cultural heritage often brings to mind artifacts (paintings, drawings, prints, mosaics, sculptures), historical monuments and buildings, as well as archaeological sites. But the concept of cultural heritage is even wider than that, and has gradually grown to include all evidence of human creativity and expression: photographs, documents, books and manuscripts, and instruments, etc. either as individual objects or as collections. Today, towns, underwater heritage, and the natural environment are also considered part of cultural heritage since communities identify themselves with the natural landscape.

Moreover, cultural heritage is not only limited to material objects that we can see and touch. It also consists of immaterial elements: traditions, oral history, performing arts, social practices, traditional craftsmanship, representations, rituals, knowledge and skills transmitted from generation to generation within a community.

Intangible heritage therefore includes a dizzying array of traditions, music and dances such as tango and flamenco, holy processions, carnivals, falconry, Viennese coffee house culture, the Azerbaijani carpet and its weaving traditions, Chinese shadow puppetry, the Mediterranean diet, Vedic Chanting, Kabuki theatre, the polyphonic singing of the Aka of Central Africa (to name a few examples).

The importance of protecting cultural heritage

But cultural heritage is not just a set of cultural objects or traditions from the past. It is also the result of a selection process: a process of memory and oblivion that characterizes every human society constantly engaged in choosing—for both cultural and political reasons—what is worthy of being preserved for future generations and what is not.

All peoples make their contribution to the culture of the world. That’s why it’s important to respect and safeguard all cultural heritage, through national laws and international treaties. Illicit trafficking of artifacts and cultural objects, pillaging of archaeological sites, and destruction of historical buildings and monuments cause irreparable damage to the cultural heritage of a country. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), founded in 1954, has adopted international conventions on the protection of cultural heritage, to foster intercultural understanding while stressing the importance of international cooperation.

The protection of cultural property is an old problem. One of the most frequently recurring issues in protecting cultural heritage is the difficult relationship between the interests of the individual and the community, the balance between private and public rights.

Ancient Romans established that a work of art could be considered part of the patrimony of the whole community, even if privately owned. For example, sculptures decorating the façade of a private building were recognized as having a common value and couldn’t be removed, since they stood in a public site, where they could be seen by all citizens.

In his Naturalis Historia the Roman author Pliny the Elder (23-79 C.E.) reported that the statesman and general Agrippa placed the Apoxyomenos, a masterpiece by the very famous Greek sculptor Lysippos, in front of his thermal baths. The statue represented an athlete scraping dust, sweat and oil from his body with a particular instrument called a “strigil.” Emperor Tiberius deeply admired the sculpture and ordered it be removed from public view and placed in his private palace. The Roman people rose up and obliged him to return the Apoxyomenos to its previous location, where everyone could admire it.

Our right to enjoy the arts, and to participate in the cultural life of the community is included in the United Nation’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Whose cultural heritage?

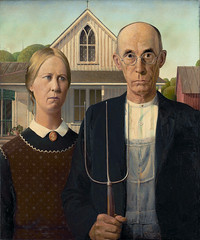

The term “cultural heritage” typically conjures up the idea of a single society and the communication between its members. But cultural boundaries are not necessarily well-defined. Artists, writers, scientists, craftsmen and musicians learn from each other, even if they belong to different cultures, far removed in space or time. Just think about the influence of Japanese prints on Paul Gauguin’s paintings; or of African masks on Pablo Picasso’s works. Or you could also think of western architecture in Liberian homes in Africa. When the freed African-American slaves went back to their homeland, they built homes inspired by the neoclassical style of mansions on American plantations. American neoclassical style was in turn influenced by the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, who had been influenced by Roman and Greek architecture.

Let’s take another example, that of the Mona Lisa painted in the early sixteenth century by Leonardo da Vinci, and displayed at the Musée du Louvre in Paris. From a modern point of view, whose national heritage does the Mona Lisa belong to?

Leonardo was a very famous Italian painter, that’s why the Mona Lisa is obviously part of the Italian cultural heritage. When Leonardo went to France, to work at King Francis I’s court, he probably brought the Mona Lisa with him. It seems that in 1518 King Francis I acquired the Mona Lisa, which therefore ended up in the royal collections: that’s why it is obviously part of the French national heritage, too. This painting has been defined as the best known, the most visited, the most written about and the most parodied work of art in the world: as such, it belongs to the cultural heritage of all mankind.

Cultural heritage passed down to us from our parents must be preserved for the benefit of all. In an era of globalization, cultural heritage helps us to remember our cultural diversity, and its understanding develops mutual respect and renewed dialogue amongst different cultures.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Cultural heritage “in crisis”

by DR. STEPHENNIE MULDER and DR. DEBORA TREIN

Have you seen the phrase “Culture in Crisis?

In recent years, particularly since the rise of ISIS’ destructive activities in the Middle East, it’s become common to see articles in the news media as well as in academic journals on the theme of “cultural heritage in crisis.” You could say it’s a booming field.

But how true is it?

It’s certainly true that cultural heritage is in danger of destruction, looting, or illicit trafficking in many places around the world. It’s also true that new types of threats to cultural heritage have developed in the last few decades.

They include,

- the easier movement of goods across national borders via online marketplaces like eBay

- the spread of global banking

- the outbreak of war and other forms of political instability and poverty

- the widespread availability of heavy machinery and explosives

Some regions—most recently the heritage-rich areas of the Middle East—have certainly experienced a marked increase in illicit trafficking in the context of ongoing political upheavals and conflicts.

But usage of the term “crisis” to describe the destruction of cultural heritage around the world is perhaps a misleading one. “Crisis” is a term that indicates a problem that has an urgent, yet temporary quality. However, the loss and destruction of cultural heritage is not new in human history and is not restricted by the duration of political instability in faraway lands. Many regions of the world, including the United States, face a longstanding and ongoing struggle to protect heritage in the face of numerous challenges, regardless of political, social, or economic security. It may be worth considering that the idea of “crisis” deceptively frames the destruction of heritage as a product of temporary instabilities that cease to be a problem once conflicts are over. In reality, conditions of “crisis” only really provide new opportunities for heritage destruction processes that were already happening and will continue happening after the “crisis” is over.

Threats to cultural heritage: war

Let’s take a closer look at these processes. Broadly speaking, there are two types of threats:

- destruction of heritage sites and objects caused by war, poverty, and development initiatives

- the looting and trafficking of objects that frequently arises out of those contexts

In wartime, destruction of heritage sites can be a result of collateral damage, for example, when a bomb targeting one location inadvertently hits another; or it can be the result of intentional damage, aimed to demoralize and insult the values and religious and cultural symbols of an enemy. It is often difficult to distinguish between collateral and intentional damage, and perpetrators may claim deliberate destruction was an accident in an attempt to avoid prosecution. In the Syria conflict, for example, you’ve probably heard about the destruction caused by ISIS. However, the majority of damage to cities and to heritage has in fact not been caused by ISIS, but by the Syrian government’s campaign of relentless aerial bombardment, which has destroyed up to 70% of the fabric of the ancient city of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

And though it’s easy to demonize a regime in a country far away, it’s important to remember that similar levels of destruction were caused by both the Axis powers and the Allies in World War II — for the Allies, most famously in Dresden, where a British and American aerial campaign in 1945 left more than 70% of the city in ruins. The neglect of the occupying U.S. forces in Iraq in 2003 famously led to the looting of the National Museum of Iraq, with thousands of objects lost, only half of which have returned, as well as the burning and destruction of Iraq’s magnificent national library, including hundreds of priceless manuscripts dating back to the 16th century. Deliberate or neglectful destruction of heritage has long been a key strategy of war, and perpetrators are rarely prosecuted for it.

The long history of the destruction of heritage shows us that the elimination of culture has always been viewed as a powerful tool of domination and as a key strategy for eliminating the value humans accord to their lives. In recent years, the destruction of heritage — whether through war, commercial exploitation, and/or looting — has been defined by UNESCO as a form of cultural cleansing. In taking human lives, oppressors erase the existence of individual people: but in destroying culture, the memory and identity of entire peoples are erased. It is not surprising to note, therefore, that the destruction of heritage is often a precursor to genocide. This is because in denying people their past, perpetrators also deny them a future.

Threats to cultural heritage: development, climate change, tourism, and natural disasters

Nevertheless, wartime destruction of heritage is only a small fraction of the overall loss of cultural heritage around the world. Much more significant and long-lasting is destruction due to urban development, mineral and resource extraction, climate change, tourism, and even natural disasters. For example, the ancient Buddhist site of Mes Aynak in Afghanistan is now threatened by Chinese mining interests, a situation made famous in a recent documentary. Similarly, the push to expand resource extraction on public lands in the United States is also causing widespread loss of heritage, as at the Bears Ears National Monument, which was controversially reduced by 85% in a decision signed by President Drumpf in December 2017.

Although many heritage sites are preserved in order to encourage tourist revenue, tourism can also cause massive destruction because of the large numbers of people it can attract and also because transforming a site into a tourist-friendly locale often profoundly transforms its meaning for local people, who may find their connections to a place have been erased. Such is the case at Dubrovnik, a city that was reconstructed by an international consortium of donors after the Balkan war and which now finds itself managing a Game of Thrones-inspired tourist influx that threatens to leave little of the original city behind, a destruction that some residents have characterized as worse than that during wartime.

Looting

If destruction of heritage during wartime is akin to a relatively sudden death, looting is like a cancer that slowly erodes it. Looting is the theft of heritage items for sale on the antiquities market, most often to wealthy private buyers in the United States and Europe. As art history professor Nathan Elkins has shown, the consequences of purchasing even small items like coins can be devastating for our knowledge about the past. Once an object is removed from its original environment, it instantly loses much of its ability to convey information about how people once lived.

Archaeologists call the environment in which an object is found, its context. Context is the object and its relationship to all the other objects and material in an archaeological site. The relationships between these objects is what enables archaeologists to recreate the past (objects that have been looted, and thereby robbed of this context can be called “ungrounded“). As such, even the smallest objects, such as ancient coins, can provide powerful evidence about the lives of people in the past. While locals are often blamed for looting, it is important to point out that local looting is often subsistence looting — looting carried out to supplement meagre incomes — and that it is only profitable because it responds to demand in wealthy countries. The antiquities market is vast, and as the Wall Street Journal reported last year, it has consequences far beyond just loss of our knowledge about the past, since much like drug trafficking, its profits fuel terrorism, criminal enterprises, and many other forms of criminal activity.

What can be done?

In repositioning the discussion of the “current crisis” to a discussion of how we are in fact currently experiencing the latest iteration of a long-standing problem with global reach, we can avoid simplistic solutions that propose that squashing the “bad guys” — for example, ISIS — will solve the destruction and looting problem once and for all. Most importantly, it allows us to focus on the real driver of destruction: the demand in wealthy countries for heritage objects — a demand that ultimately fuels the entire antiquities trade — and the lax legislation that enables that trade to flourish. It also permits a conversation about related issues, for example the lack of public education about the antiquities trade, or problematic distinctions such as that between art — largely considered to be a private commodity subject to market demand, versus heritage — which is typically framed as “universal” and the patrimony of all.

Understanding that cultural heritage has been under threat for a very long time allows us to avoid short-term, crisis-based responses, and enables us to craft long-lasting, systemic solutions.

Additional resources:

Zainab Bahrani, “Desecrating history,” The Guardian, April 9, 2008.

Trinidad Rico, “Heritage at Risk: The Authority and Autonomy of a Dominant Preservation Framework,” in Heritage Keywords: Rhetoric and Redescription in Cultural Heritage, Kathryn Lafrenz Samuels and Trinidad Rico, editors, Boulder, University of Colorado Press, 2015, pages 147–162.

Blow it up: cultural heritage and film

by A.O. SCOTT

Empty-eyed in a desolate landscape

One of the most famous endings in cinema—one of those images you recognize immediately, even if you’ve never seen the whole movie—is the last shot of the original 1968 version of “Planet of the Apes.” Charlton Heston, to his howling dismay, discovers what attentive viewers might have suspected all along. He didn’t crash into a planet in some remote corner of the galaxy, where gorillas and chimpanzees rule over humans: he’s been home the whole time, on a dystopian future earth. The proof is the sight of the Statue of Liberty, once a beacon of hope and now a ruin half-buried in the sand.

It’s a horrifying tableau, arguably more powerful than anything else in the film, which is, all in all, an over-earnest, pulpy adaptation (directed by Franklin J. Schaffner), of Pierre Boulle’s science-fiction bestseller. It doesn’t stand up very well. The allegory is problematic, the ape masks are silly, and the movie survives as a camp artifact, except for that final moment. There is something undeniably horrifying about seeing the Lady in the Harbor standing empty-eyed in a desolate landscape, a feeling of dreadful sublimity that inverts the awe that might accompany seeing her in real life, say from the deck of a tourist ferry en route to Liberty Island.

The horror is cautionary, and also titillating, in the way that science fiction thrills us by inviting us to imagine the worst. Movies and their audiences revel in spectacles of destruction, routinely treating us to the obliteration of monuments, landmarks, cities, entire planets. We can enjoy the wreckage because we know it isn’t real, while at the same time feeling a tremor of plausibility. What if it really happened?

But of course it does really happen. The history of modern warfare—to say nothing of older annals of sacking and pillage—is testament to the vulnerability not only of human populations, but also of everything human beings have built, including cherished monuments, museums, and architectural masterpieces. Accidents and natural disasters also claim their share of the spoils. Recently, video of flames shooting from the roofs of Notre Dame de Paris and the National Museum of Brazil in Sāo Paolo provoked a sickening sense of simultaneous incredulity and déjà vu. This is the kind of thing we’re used to seeing in movies—the result of alien invasions, asteroid collisions, zombie apocalypses or diabolical super-villain conspiracies. The movies, in other words, is where we like to think this kind of disaster belongs. They prepare us for calamity even as we like to think they inoculate us.

Emblems of vanity

Real-world landmarks are repositories of history, meaning and cultural and species identity. All of that is comprehended in the phrase “heritage site,” which idealistically assumes a global consensus that may or may not exist. (If nothing else, the shelling of the medieval Croatian city of Dubrovnik by Serb forces during the Balkan Wars of the 1990s and the obliteration of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, Afghanistan by the Taliban in 2002 suggest that the values that protect such sites are as fragile as the sites themselves). They serve as symbols of what is unquantifiably threatened by disaster. They stand for civilization in the broadest sense, as well as for the particular civilizations that produced them. Thus the Statue of Liberty in Planet of the Apes doesn’t just represent the ideal of American democracy or the Republican legacy of France, but also a wider human ambition, an impulse to leave behind outsized tokens of our presence on the planet.

Mocking this ambition is also a long-standing cultural habit. The durability of these massive structures of metal or stone means that they are likely to outlast the societies that erected them, and thus to survive as emblems of vanity, futility and insignificance. What Charlton Heston says when he sees the ruined Lady Liberty is “You finally, really did it. You maniacs! You blew it up!” I understand him to be addressing not the apes, but his fellow humans, whose self-destruction paved the way for their displacement by another species. And so an embodiment of noble possibility becomes a reminder of failure and disgrace.

The rebooted, 21st-century “Planet of the Apes” franchise retells the story from a decidedly more ape-friendly perspective. A decisive battle in the revolution against human domination takes place on the Golden Gate Bridge. The structure survives the mayhem, but the sight of its span over-run by angry, rebellious primates signifies its passage from a monument of our engineering ingenuity into an omen of our obsolescence. Like the Statue of Liberty in the earlier version, the survival of the bridge is an index of our destruction. This time, what is dramatized is exactly how we did blow it all up.

This kind of imagery—the hollowed-out heritage site, evacuated of the human presence that had provided it with a function and a meaning—has recently become a staple of the zombie movie, arguably the most popular disaster subgenre of the 21st century so far. The final scene of “28 Weeks Later” (2007) shows a zombie bacchanal at the foot of the Eiffel Tower (in the earlier “28 Days Later,” the infected flesh-eaters had rampaged through the landmarks of London). The non-zombie survivors in “Zombieland: Double Tap” (2019)—sequel to the popular, spoofy “Zombieland” (2009)—find temporary refuge in the White House and at Graceland. Their irreverent presence in those secular pilgrimage sites is funny and horrifying at the same time. Look how easy it is for the grand achievements of American democracy and American pop culture to become derelict, reduced to museums without patrons, tombs without mourners.

Fantasies of destruction

And look how easy it is to imagine not just the emptying out of those edifices, but also their physical obliteration. Since the beginning, cinema has devoted a portion of its innovative energy to refining the machinery of fantasy, and the rise of digital effects in the past 30 years or so has put fantasies of destruction at the fingertips of hacks and visionaries alike. It now takes relatively little effort to conjure a digital city in order to lay waste to it.

The destruction has become almost banal. The blockbusters of the 90s and early 2000s represent an orgy of destruction. The Golden Gate Bridge was destroyed in “X-Men,” the White House in “Armageddon” and again in “2012,” Big Ben in “V for Vendetta,” the Statue of Liberty in “Cloverfield.” This is a partial list, and what’s striking is how trivial so many of those movies now seem. Even in the wake of the September 11 attacks—which people at the time said “was like something out of a movie”—the appetite for falling skyscrapers and glass-shattering fireballs did not abate. On the contrary, the ability of reality to emulate movie nightmares spurred the production of more such nightmares, as if their inoculating power required an ever higher dose.

In her essay “The Imagination of Disaster,” first published in 1965, when science fiction movies were preoccupied with the prospect of nuclear annihilation, Susan Sontag wrote that “we live under continual threat of two equally fearful, but seemingly opposed, destinies: unremitting banality and inconceivable terror.” That is still true, except that now it may no longer be possible to tell which is which. And that may be partly because, when it comes to the things we have built to celebrate our passage through history, we may dread their loss even as we take them for granted. We contemplate their destruction in order to work out—and also, somehow, to avoid thinking too hard about—a deeper ambivalence about ourselves.