10.6: Dada and Surrealism (I)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147832

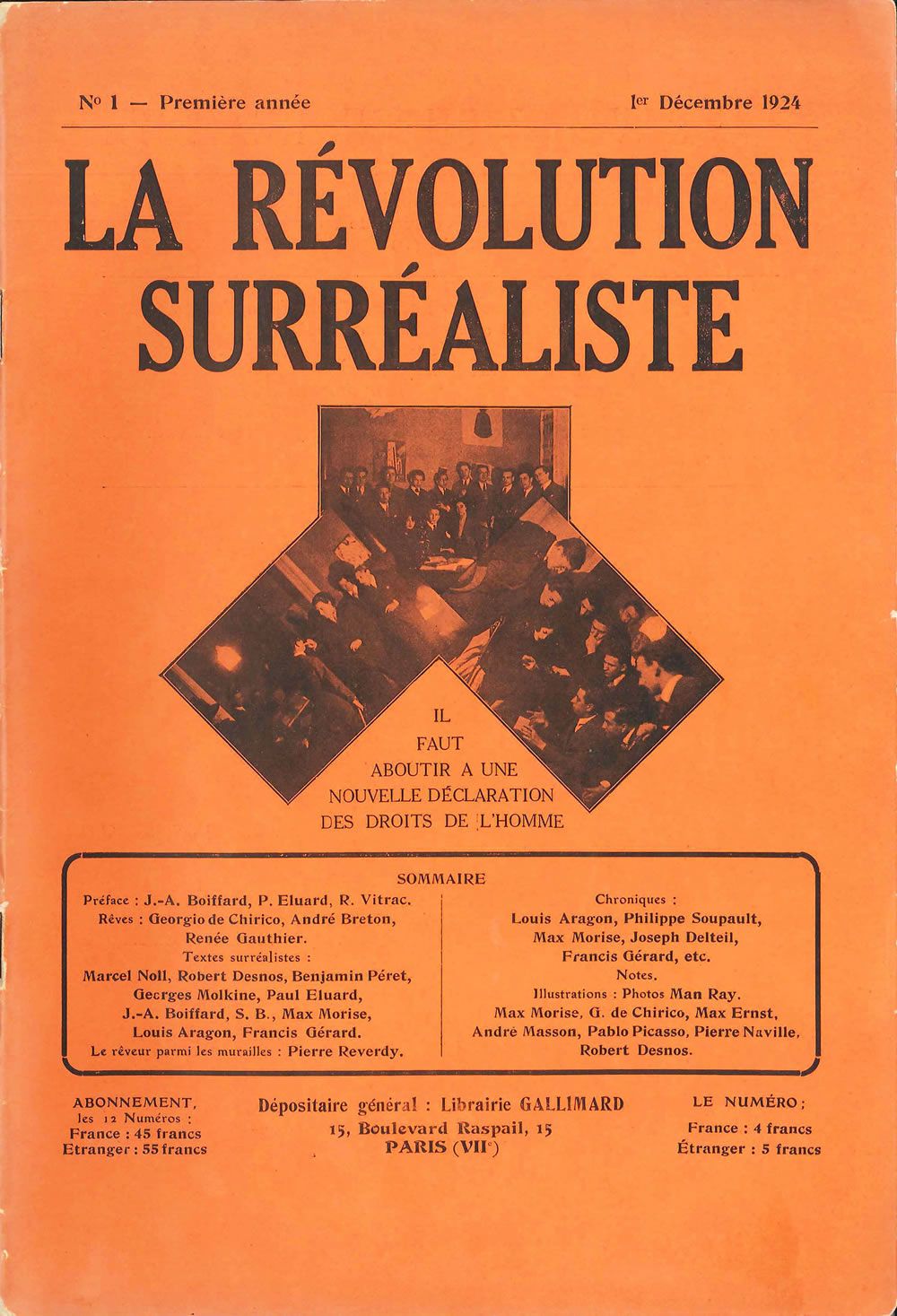

Dada and Surrealism

These two movements reconceptualized what art could be, impacting art making through today.

c. 1913 - 1939

Dada

This international "anti-movement" of radical young artists claimed that virtually anything could be art.

c. 1913 - 1920

A beginner's guide to Dada

Introduction to Dada

by DR. STEPHANIE CHADWICK

Art as provocation

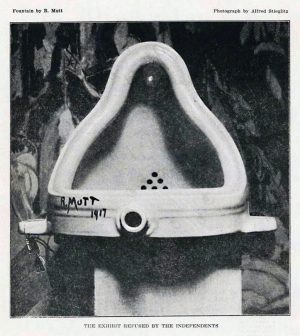

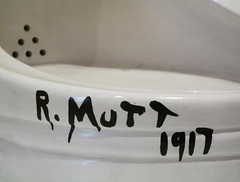

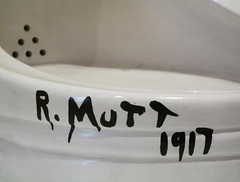

When you look at Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, a factory-produced urinal he submitted as a sculpture to the 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, you might wonder just why this work of art has such a prominent place in art history books.

You would not be alone in asking this question. In fact, from the moment Duchamp purchased the urinal, flipped it on its side, signed it with a pseudonym (the false name of R. Mutt), and attempted to display it as art, the piece has generated controversy. This was the artist’s intention all along—to puzzle, amuse, and provoke his viewers.

Fountain was submitted to the Society of Independent Artists, one of the first venues for experimental art in the United States. It is a new form of art Duchamp called the “readymade”— a mass-produced or found object that the artist transformed into art by the operation of selection and naming. The readymades challenged the very idea of artistic production, and what constitutes art in a gallery or museum. Duchamp provoked his viewers—testing the the exhibition organizers’ liberal claim to accept all works with “no judge, no prize” without the conservative bias that made it difficult to exhibit modern art in most museums and galleries. Duchamp’s Fountain did more than test the validity of this claim: it prompted questions about what we mean by art altogether—and who gets to decide what art is.

A world of questions

Duchamp’s provocation characterized not only his art, but also the short-lived, enigmatic, and incredibly diverse transnational group of artists who constituted a movement known as Dada. These artists were so diverse that they could hardly be called a coherent group, and they themselves rejected the whole idea of an art movement. Instead, they proclaimed themselves an anti-movement in various journals, manifestos, poems, performances, and what would come to be known as artistic “gestures” such as Duchamp’s submission of Fountain.

Dada artists worked in a wide range of media, frequently using irreverent humor and wordplay to examine relationships between art and language and voice opposition to outdated and destructive social customs. Although it was a fleeting phenomenon, lasting only from about 1914-1918 (and coinciding with WWI), Dada succeeded in irrevocably changing the way we view art, opening it up to a variety of experimental media, themes, and practices that still inform art today. Duchamp’s idea of the readymade has been one of the most important legacies of Dada.

Dada readymades

In a 1936 essay titled “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” the German philosopher and cultural theorist, Walter Benjamin, proclaimed that the industrial age had changed everything about the way we view art. He believed that new technologies for mass production and media (such as photography) would invalidate the remnants of classical artistic traditions that were still being promoted by institutions such as art academies and museums.

Duchamp’s idea of the readymade, which he began exploring with works such as Bicycle Wheel and Bottle Rack as early as 1913, confronted these issues head on—subjecting the idea of art to intense scrutiny.

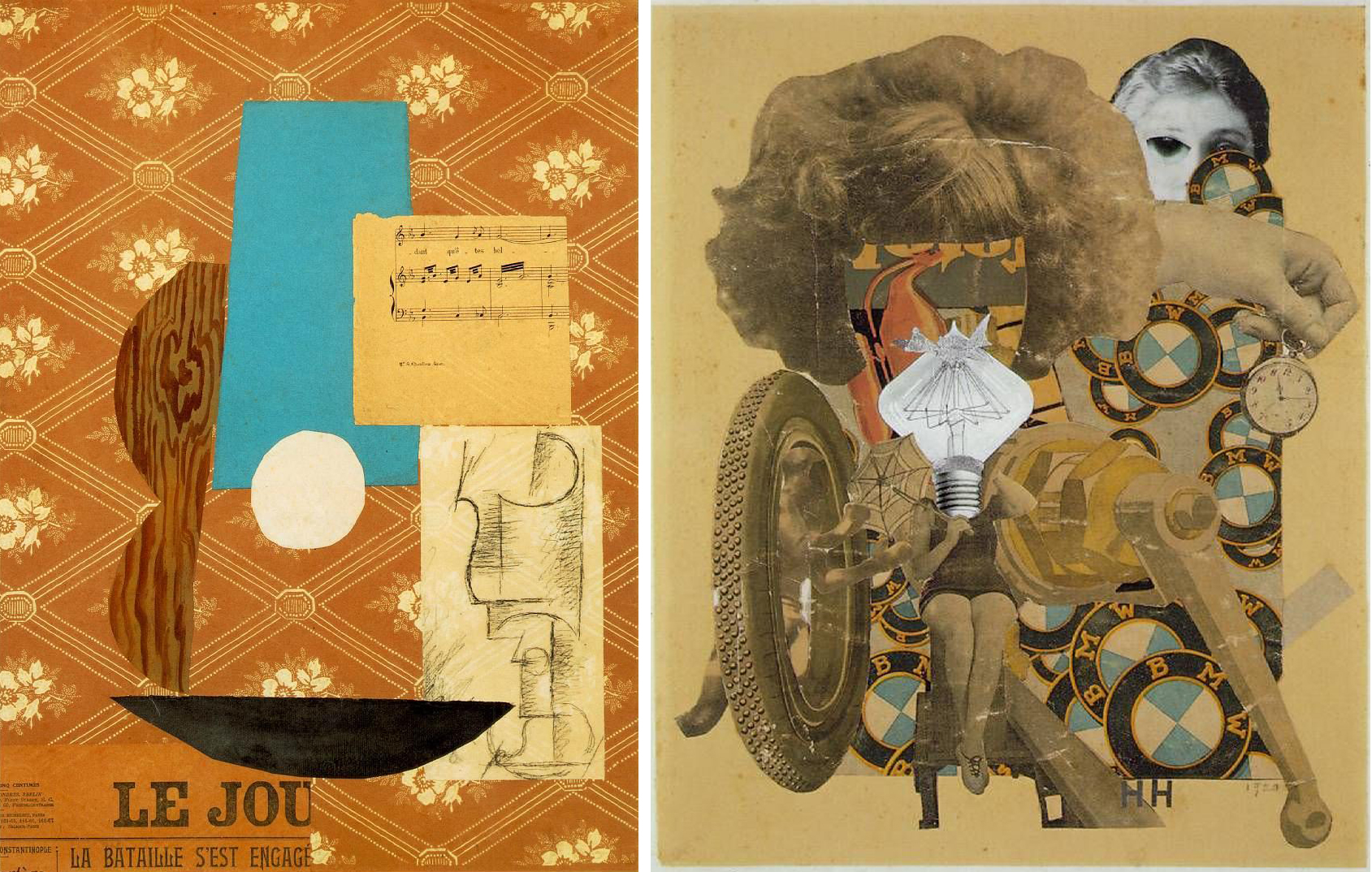

Although Duchamp coined the term “readymade” and was the first to show mass produced objects as art, he drew inspiration from Braque, Picasso, and the other Cubists then working in Paris, who had already begun incorporating everyday items from mass culture (such as newspaper and wallpaper) into their abstracted collages.

International collaboration

Sharing and adapting characterized the key approaches of Dada artists, and Duchamp’s use of articles from everyday life caught on among the various Dada collectives, though each used the readymade in ways that reflected their own group’s specific artistic concerns.

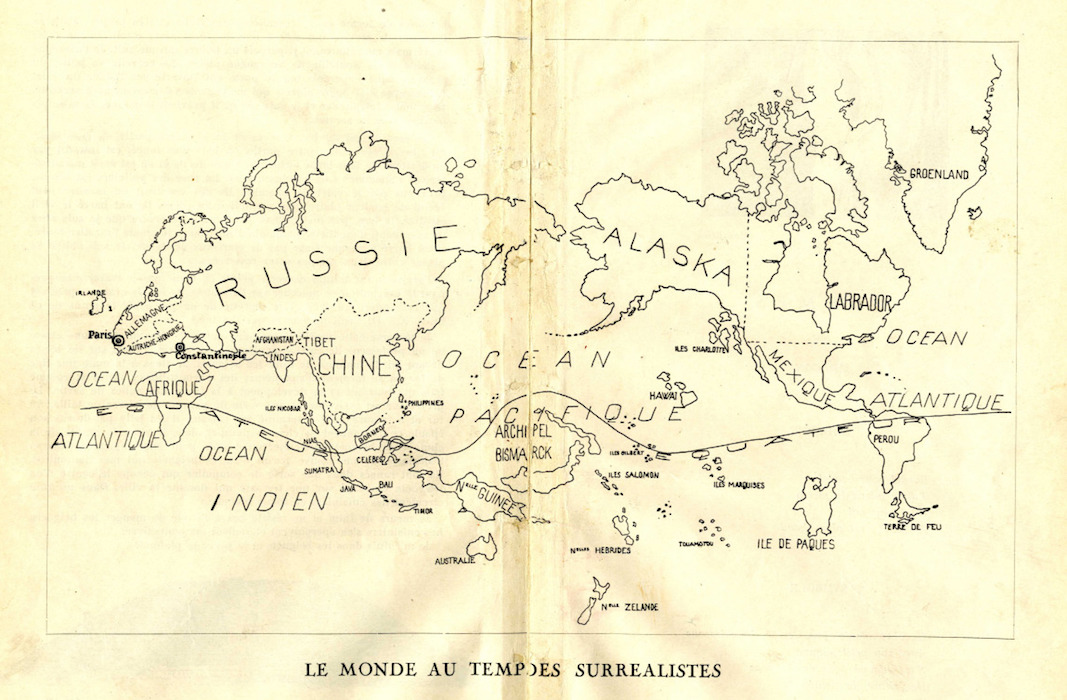

Art historian Leah Dickerman has demonstrated that Dada can best be understood by looking at its distinct manifestations in six urban centers. The Dada movement officially began in Zurich, a city in politically neutral Switzerland where many artists and intellectuals fled during World War I. From there, the movement radiated outward to the other groups in Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, and Paris—each of which had members in communication with the other groups.

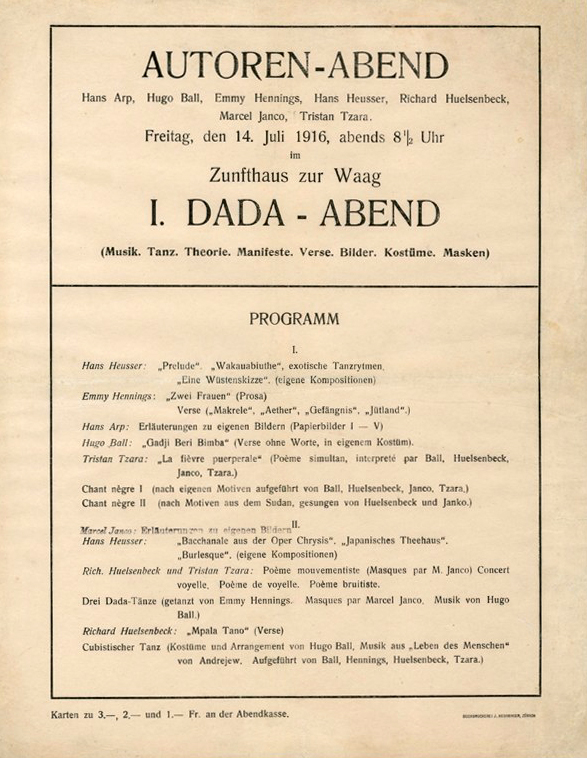

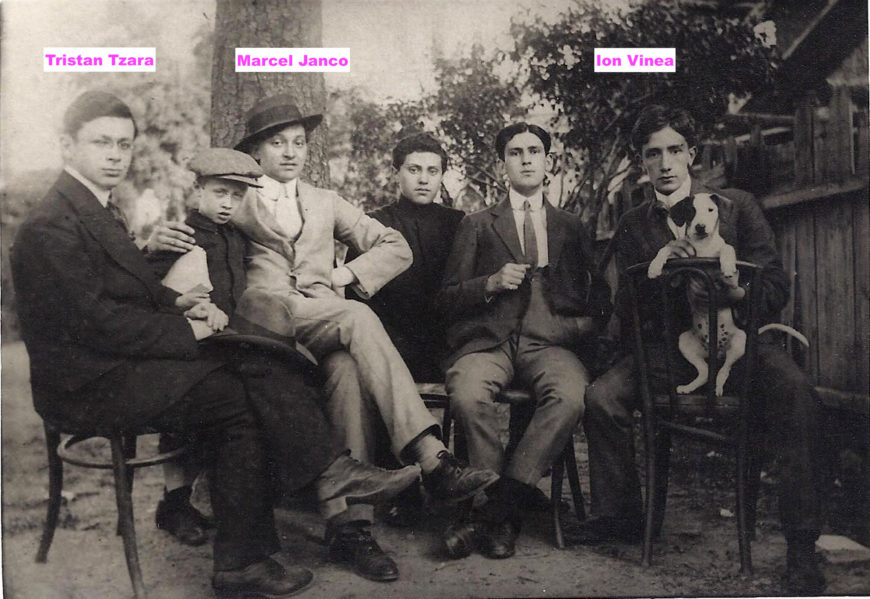

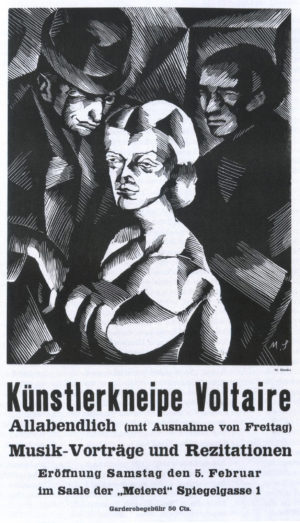

Zurich Dada

Beginning in 1916, Zurich Dada centered around the Cabaret Voltaire, which provided a creative haven for exiled artists and others to explore new media and performance while critiquing what they saw as the predominant “rational” culture that led to the irrational horrors of the war. Members of this group included Hugo Ball (German), Emmy Hennings (German), Hans (also known as Jean) Arp (from Alsace, a contested territory between France and Germany), Sophie Taeuber (later to become Sophie Taeuber Arp, Swiss), and Tristan Tzara (Romanian). It was their raucous, irreverent, and absurd performances ranging from sound poetry to dances in costumes modeled after Native American and other non-European ritual garments, that gained the attention of the avant-garde art world. In addition to their collaborative art practices, exhibitions, and performances, the artists in Zurich published a journal and other graphic materials to spread their ideas.

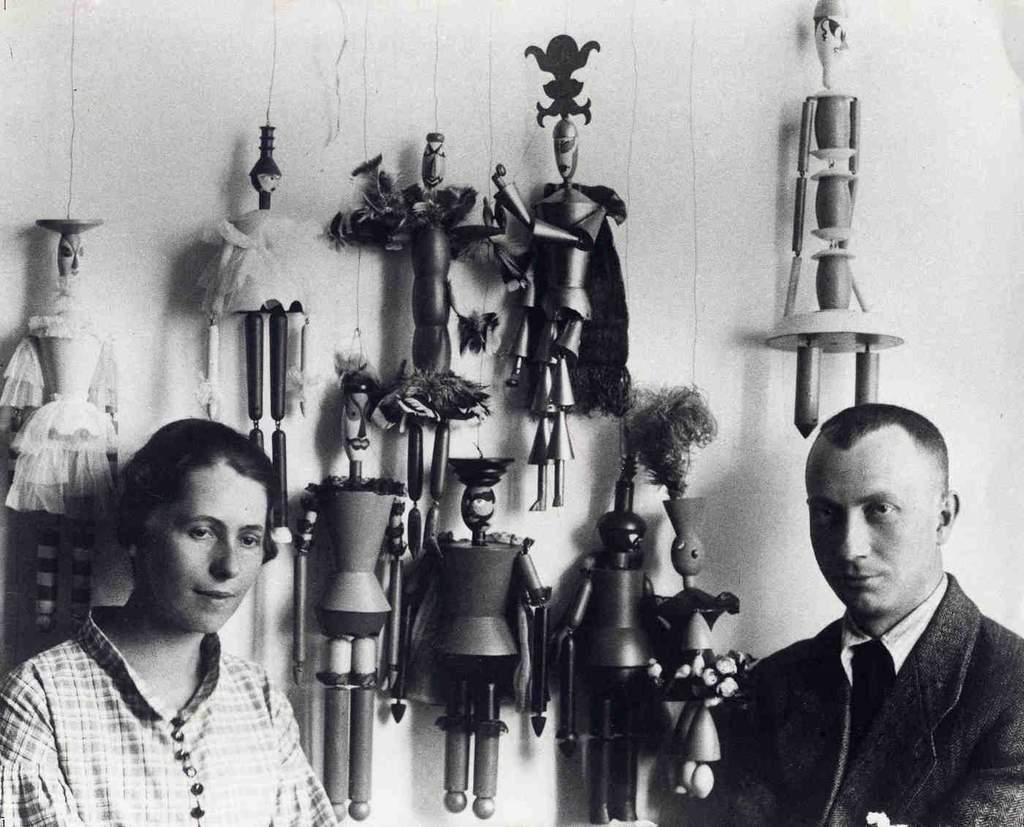

Taeuber and Arp

Sophie Taeuber produced an incredible collection of marionettes and worked in media such as textiles and wood, which had traditionally been relegated to the category of “craft” (ostensibly a “low” art associated with “women’s work”) by European academic art institutions. Hans/Jean Arp moved away from his previous interest in German Expressionism to develop what he called “chance collages,” in which it is said that he tossed torn or cut paper squares onto a larger sheet of paper on the floor and then glued them in whatever formation they landed. Taeuber and Arp also produced abstract wooden sculptures, many of which resembled organic forms or, alternatively, mechanical forms such as mannequin heads.

In works such as these, Zurich Dada demonstrated a skeptical attitude toward rationality and intention, found strategies to explore abstraction, and displaced the artist’s hand (that is, the direct connection to the work of art that was the basis of the “aura” that Benjamin associated with traditional artworks in museums and galleries). Instead of the specialized materials of fine art such as oil paint and marble, these artists favored mass media imagery and everyday commercial materials such as paper. They sought to integrate art and life more closely in order to critique the effects that modern industrialization—factory labor, mass production, and rapid urbanization—had wrought on society. These industrial advances raised the standard of living for many, but had a devastating impact on the battlefield where millions died due to poison gas and other types of newly efficient weapons.

Berlin Dada

Dada arrived in Germany in 1917 when Richard Huelsenbeck, a German poet who had spent time at the Café Voltaire, brought the ideas he encountered in Zurich to Berlin. Here, Dada became even more overtly political. Using the readymade, new photographic technologies, and elements from everyday life, including mass media imagery, Huelsenbeck and his collaborators critiqued modern bourgeois society and the politics that had led to the First World War.

Berlin Dadaists embraced the tension and images of violence that characterized Germany during and after the war, using absurdity to draw attention to the physical, psychological, and social trauma it produced. Employing strategies ranging from a Cubo-Futurist rendering of form to mixed-media assemblage, they satirized the immorality and corruption of the social elite, including cultural institutions such as museums. Many of these works were featured alongside manifestoes and other textual works in Dada journals.

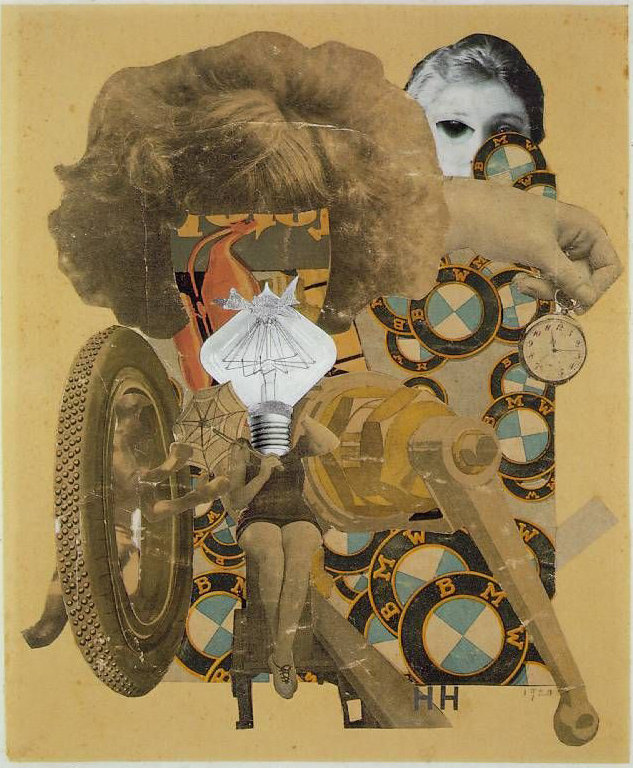

During the Weimar Republic, artists such as Hannah Höch produced collages using imagery from magazines and other mass media to provoke the viewer to critically evaluate and challenge cultural norms.

One of the most transformative Berlin Dada practices—one that continues to inform contemporary art today—was the invention of mixed media installations. This began in earnest with the First International Dada Fair in 1920, which featured an assortment of paintings, posters, photographs, readymades, and two- and three-dimensional mixed media art.

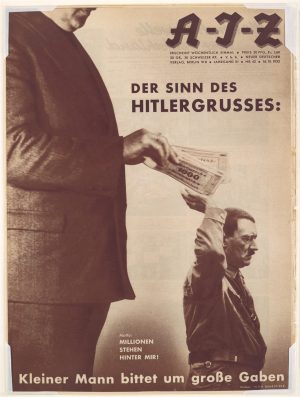

In Berlin, artists such as John Heartfield and George Grosz, political agitators who had anglicized their names in protest of overzealous German nationalism, continued their Dada cultural interrogations into the 1930s to combat the rise of the National Socialist (Nazi) Party. Because Heartfield, Grosz, and other artists involved in Berlin Dada embraced Communism as the solution to fight fascism, they combined Dada strategies with the radical agitprop (agitational propaganda) that had been used to mobilize public opinion against traditional bourgeois society during the Russian Revolution and the establishment of the Soviet Union. Heartfield is best known for his use of photomontage. In the hands of Heartfield and other Dadaists, mainstream advertising, high society publicity, and fascist propaganda was turned on its head, providing readers with humorous, yet sobering exposés.

Hannover Dada

Although a spirit of collaboration characterized Dada in all its manifestations, Hannover Dada is best known for the collages and three-dimensional assemblages of one artist: Kurt Schwitters. Labeling his art “Merz” (a term he extracted from the word Kommerz, German for “commerce”), his art reflected a desire to explore the connections between human experience, memory, and objects in the world—particularly discarded scraps of newspaper, movie tickets, or other scrapped consumer goods. Schwitters gave these cast-off everyday objects new life in his collages that retained a dialogue with painting, formal abstraction, and sculpture.

This approach is particularly visible in his Merzbau, a project that he worked on for years in his Hannover home before having to abandon it for subsequent efforts in Norway and England when he was forced by the Nazis to flee Germany. Within this cottage-sized three-dimensional assemblage he incorporated abstract structures reminiscent of German Expressionist film and stage design along with objects that served as souvenirs of key moments and relationships, expressing also his interest in material, physical, and spiritual interactions.

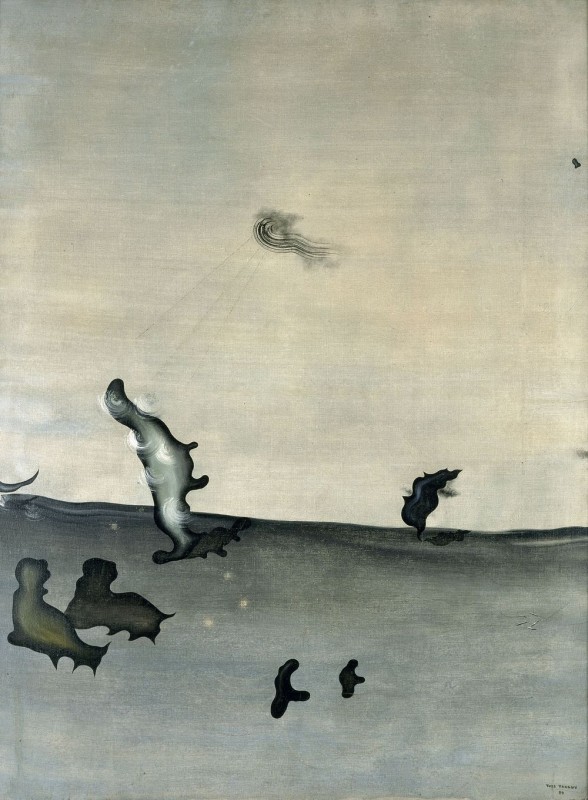

Cologne Dada

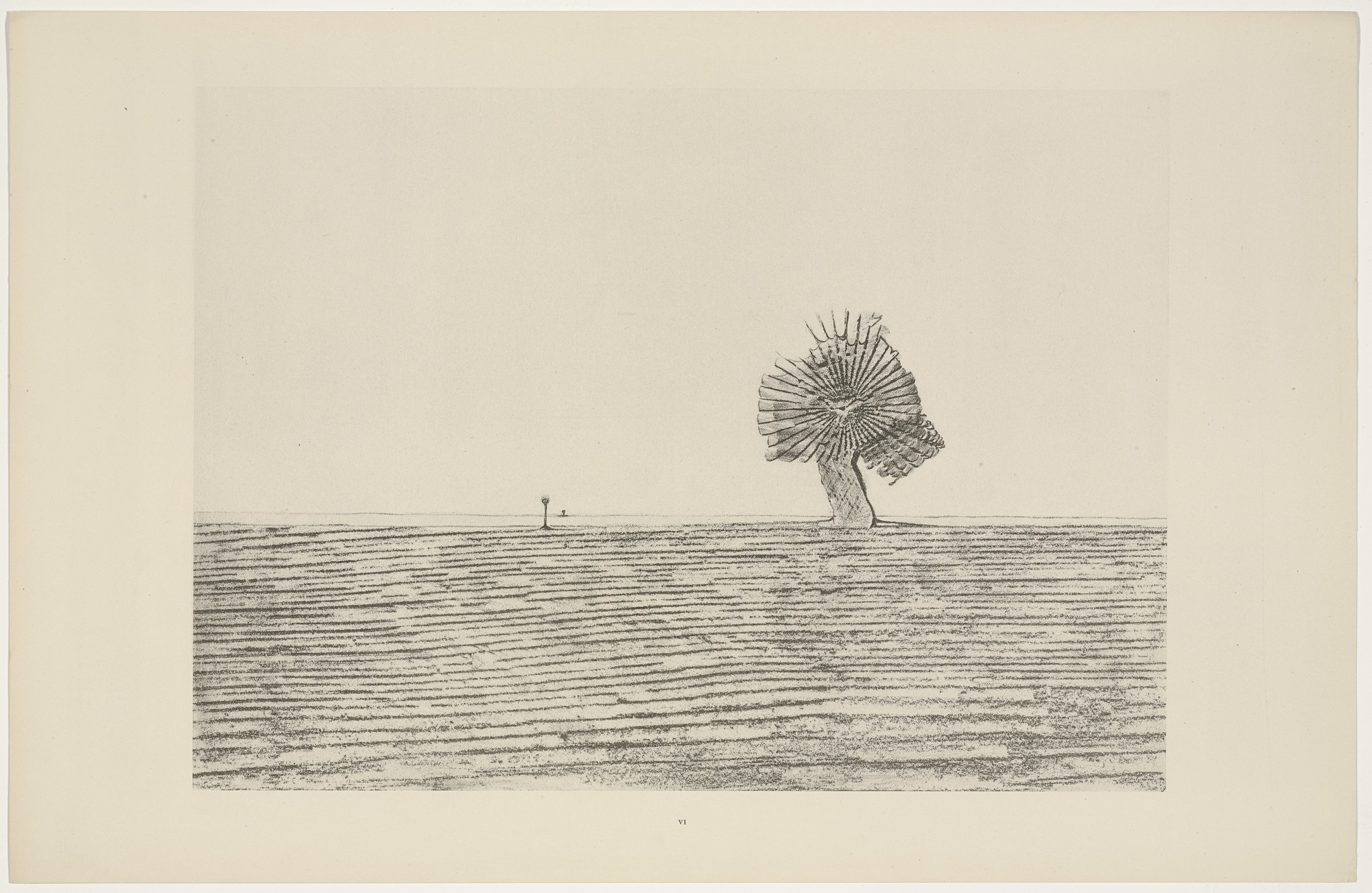

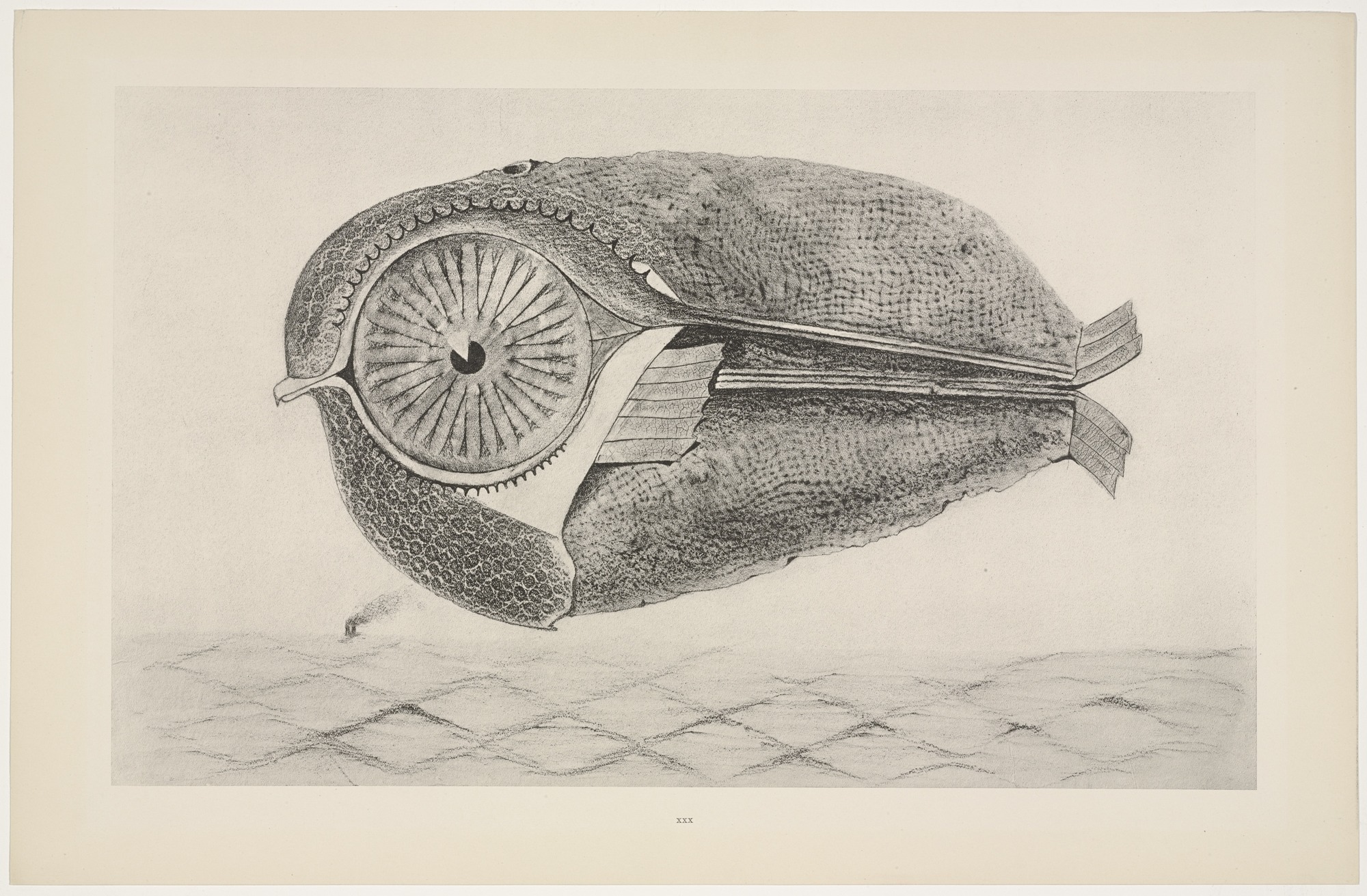

Dada in Cologne (a city in western Germany) is most closely associated with the diverse artworks of Max Ernst, an artist who produced a prolific body of work that included frotage (rubbings), painting, collage, and mixed media assemblage. These works, many of which explored the absurd and suggested fantastic creatures, dwellings, and landscapes, are often associated with Surrealism, a movement with which he was also affiliated. Because Ernst worked in Germany and France, fled to the United States during World War II, and later returned to Europe, his work impacted art on both sides of the Atlantic and can be found in collections around the world.

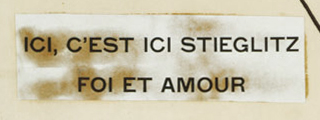

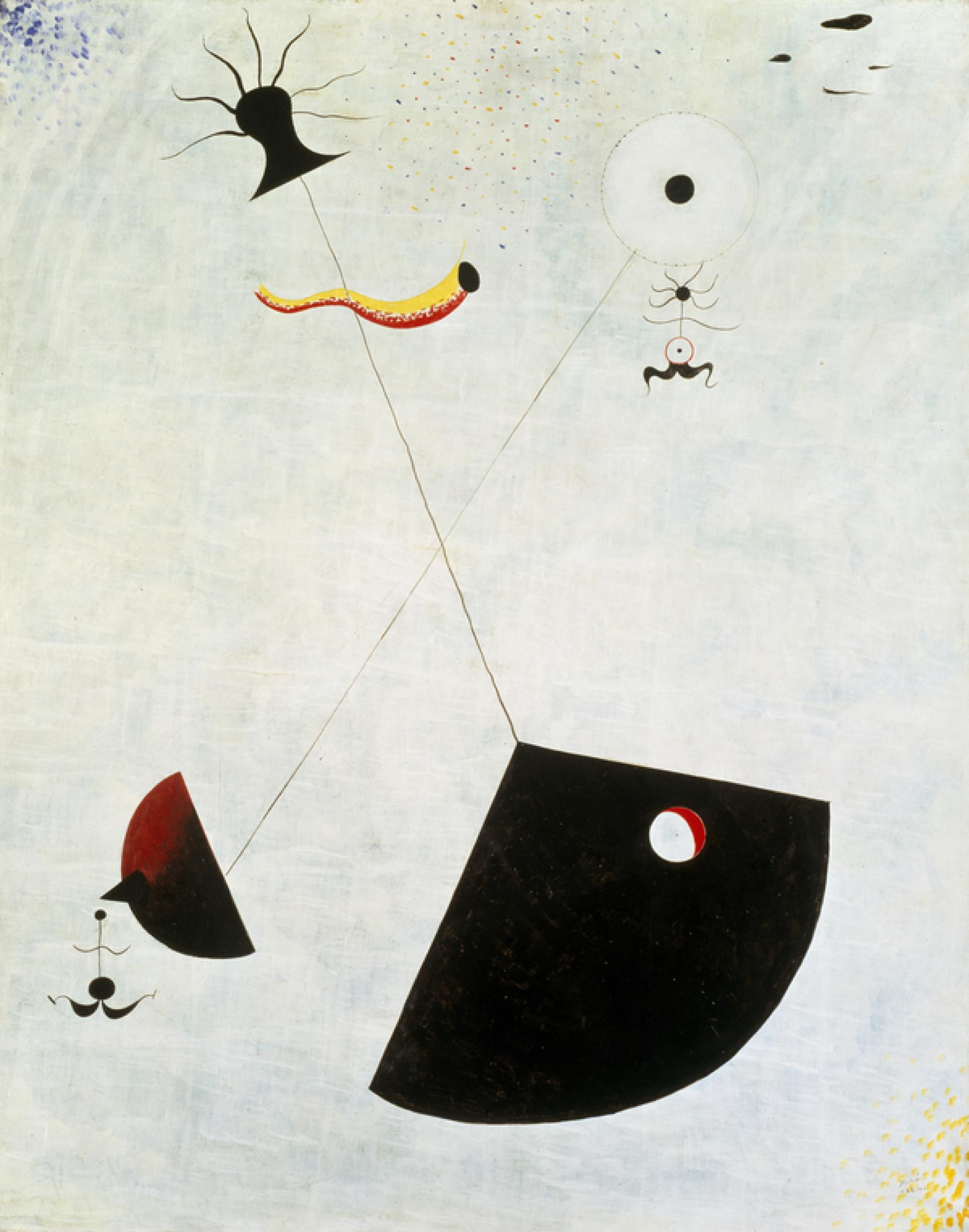

New York and Paris Dada

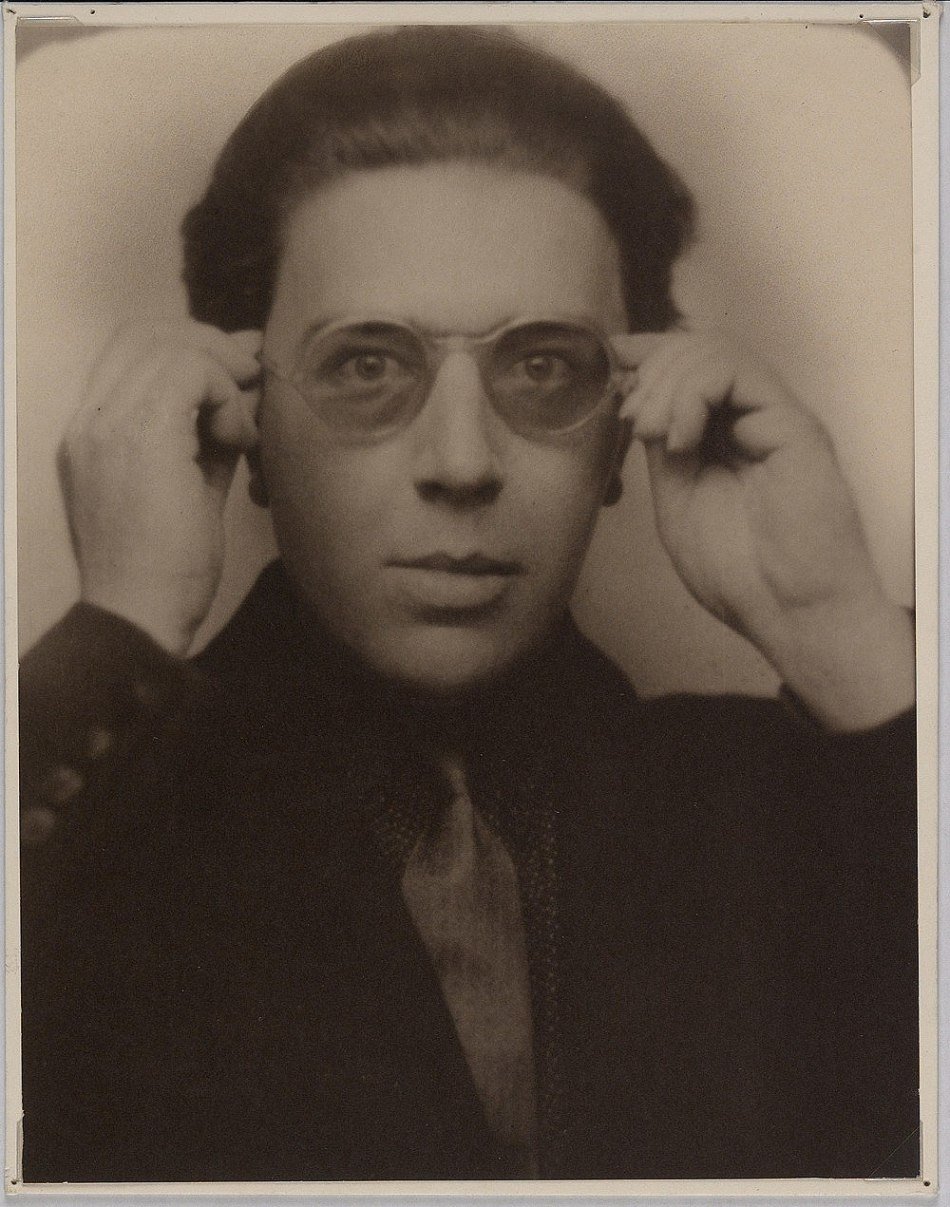

New York Dada, where we began this discussion, lost its momentum when its two primary leaders, Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, returned to Europe after World War I. In Paris, the two leaders joined like-minded artists and former exiles to continue their raucous, yet playful, interrogation of art and culture. More attuned to the approaches of the Zurich and New York groups, Paris Dada centered around spectacle and was less overtly political than Dada in Germany. The group’s performances, photographs, mixed media collage, and installations nevertheless emphasized the absurd and challenged social norms. These interests, combined with the emerging appeal of investigating imagery that reflects psychological states, led many of the Paris Dada group (including Man Ray, best known for his experimental photographs) to join the Surrealists who, led by writer Andre Breton, made Paris the center of their activities.

Dada and Its Legacies

Many of the artists who identified with Dada went on to become Surrealists. Because of this, and the relatively brief duration of the Dada phenomenon, it took some time for subsequent artists and historians to appreciate its value. In retrospect, however, we can see the reverberations of Dada throughout the twentieth century, and it has been one of the main contributors to contemporary art practices since its revival as Neo-Dada in the 1960s.

Additional resources:

World War I and Dada from The Museum of Modern Art

John Heartfield, Der Sinn des Hitlergrüsses at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Marcel Duchamp on The Museum of Modern Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Leah Dickerman and Brigid Doherty, Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris (Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2005)

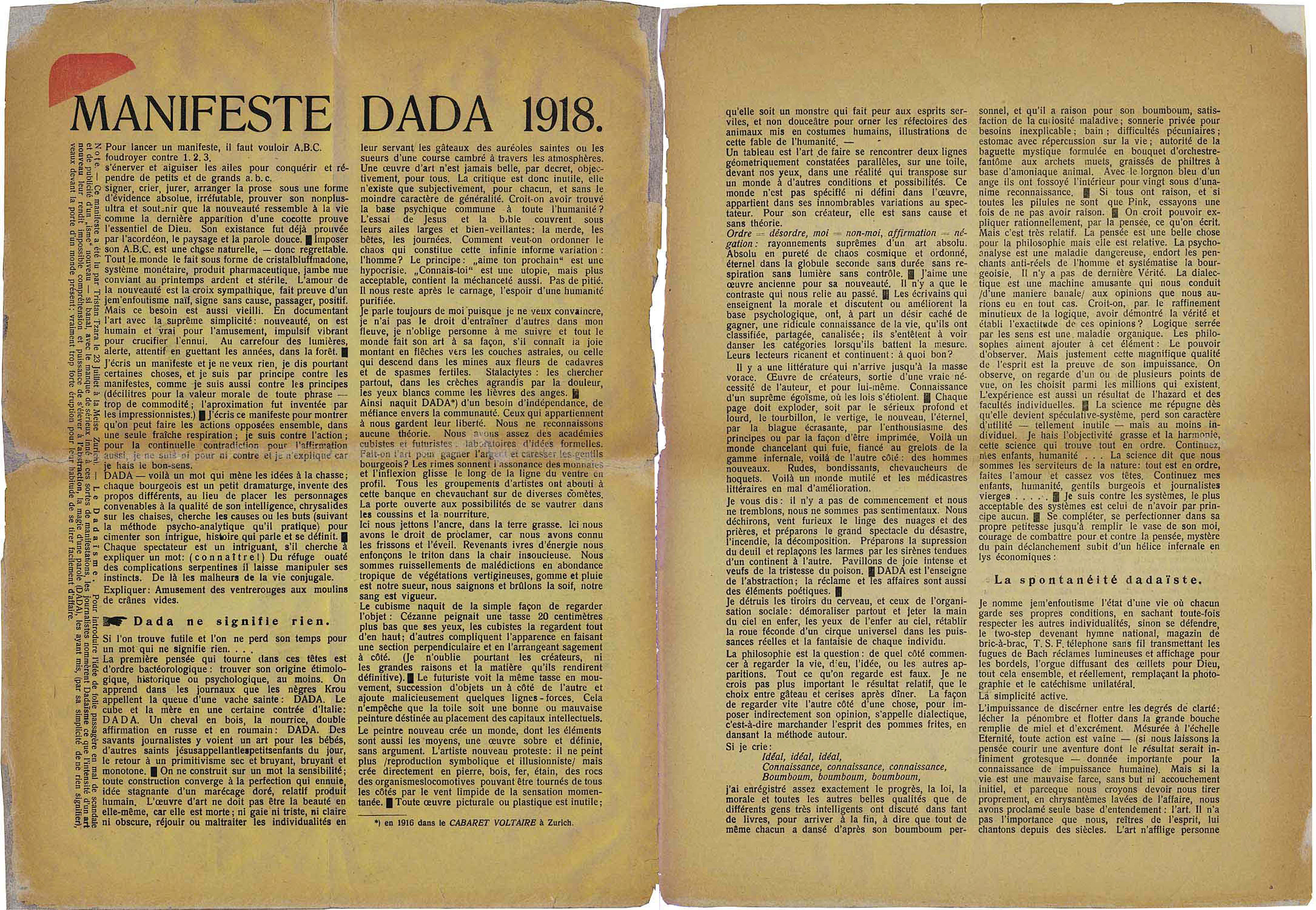

Dada Manifesto

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

The poet Tristan Tzara was a strong advocate of the international Dada movement, but his Dada Manifesto of 1918 (which you can read in full here) appears to be complete nonsense. It is, in fact, just that — but in a really interesting way that perfectly serves the goals of the Dada movement.

An anti-manifesto manifesto

A manifesto (derived from a Latin word meaning “clear,” which is ironic in this case) is a document that states the beliefs and objectives of a group. Many manifestos are political, but artists began issuing manifestos declaring their aesthetic aims in the 1880s. Tzara paradoxically introduces his Dada manifesto with a rant against manifestos and their lists of demands:

To put out a manifesto you must want: A. B. C. / fulminate against 1. 2. 3. / fly into a rage and sharpen your wings to conquer and disseminate little abcs and big abcs / sign, shout, swear, organize prose into a form of absolute and irrefutable evidence, to prove your non plus ultra.

Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918 [1]

The righteous zeal of manifestos repels Tzara, as does the way manifestos seek to impose a course of action on others. “To impose your A. B. C. is a natural thing — hence deplorable,” he insists, rather oddly, since we are used to thinking of what is “natural” as good, not deplorable.

After this opening rant Tzara slides into one of the many bewildering, free-associative broadsides that are scattered throughout the manifesto: “Everybody does it in the form of crystalbluffmadonna, monetary system, pharmaceutical product, bare leg advertising the ardent sterile spring [season].” These seemingly senseless interludes are partly a Dada strategy to prevent any extended trains of rational thought, but there is also some method to the madness. Tzara here evokes all sorts of ways that human beings find comfort, purpose, and meaning in life, such as religion, money, technology, drugs, sex, and consumerism. These false comforts are, implicitly, as deplorable as the self-righteousness that produces manifestos.

For Tzara, Dada emphatically does not want to participate in such false comforts or organized social movements, so what he is writing is an anti-manifesto manifesto:

I write a manifesto and I want nothing, yet I say certain things, and in principle I am against manifestos, as I am also against principles.

Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918

Violating two basic principles of logic, Tzara here contradicts his own terms (writing a manifesto that wants nothing), and denies his own premises (he is against the very principles that makes him reject manifestos). With this sentence, Tzara introduces us to the main strategy of Dada: continuous contradiction.

Continuous contradiction

A core idea behind Dada is absurdism, a philosophical position that recognizes an inherent conflict between humankind’s constant need to search for meaning and purpose in life, and the lack of any such (knowable) meaning or purpose. “Supposing life to be a poor farce, without aim,” Tzara writes. Throughout history, people have attempted to assuage their psychological distress by asserting various meanings and purposes for life, but these are themselves contradictory (the way two different religions frequently are), and there is insufficient evidence for any of them.

Dada is based on the recognition and acceptance of the meaninglessness of life, and the last thing Dadaists want to do is to create another illusion to comfort people with a sense of purpose when there is none. The only gesture left to Dada is to tear down other people’s systems and illusions, as Tzara recognizes in scattered statements that almost read as genuine attempts at an absurdist or nihilist manifesto:

There is no ultimate truth… Does anyone think that, by a minute refinement of logic, they have demonstrated the truth and established the correctness of their opinions? … I detest greasy objectivity, and harmony, the science that finds everything in order… I am against systems, the most acceptable system is on principle to have none.

Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918

Perhaps the closest that Tzara comes to making a graspable statement of the Dada creed is this:

I write this manifesto to show that people can perform contrary actions together while taking one fresh gulp of air; I am against action; for continuous contradiction, for affirmation too, I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense.

Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918

Even in what should be a straightforward statement of the main strategy of Dada, “continuous contradiction,” Tzara recognizes that he would, in effect, be contradicting himself if he did not contradict himself and affirm affirmation as well. The fact that this is an absurd internal contradiction is not a logical flaw; it is the essence of Dada.

The strategy of continuous contradiction accounts in part for why so much of Dada art is offensive. That offense arises out of our consciousness of social conventions being broken or sacred cows being desecrated. Examine the works illustrated here and in the essays on Dada performance, pataphysics, collage, readymades, and politics. Notice how they violate all sorts of conventions and mock the many ways that humanity tries to make sense of and find purpose in life: religion, culture, fashion, nationalism, war, art, consumerism, technology, science, family, love, etc.

Radical individualism

Although Dada considers all human systems to be vain attempts to allay our terror at the meaninglessness of existence, Tzara is not a complete nihilist. Scattered throughout the manifesto are statements that suggest his belief in radical individualism. Tzara calls humankind an “infinite and shapeless variation.” There are no universal values, truths, or tastes: “Criticism is useless, it exists only subjectively, for each person separately, without the slightest character of universality. Does anyone think they have found a psychic base common to all humankind?” Any attempt to generalize knowledge or assert a universal human ideal is in vain:

If I cry out: Ideal, ideal, ideal / Knowledge, knowledge, knowledge, / Boomboom, boomboom, boomboom, I have given a pretty faithful version of progress, law, morality, and all other fine qualities that various highly intelligent people have discussed in so many books, only to conclude that after all everyone dances to their own personal boomboom, and that the writer is entitled to his boomboom.

Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918

The last couple of clauses begin to suggest a value and a purpose: “everyone dances to their own personal boomboom,” and each of us is entitled to our own boomboom. Accepting such radical individualism would result in the highest state possible: freedom at least from subservience to anyone else’s system — political, religious, philosophical, ethical, economic, sartorial, sexual, or social. “Dada was born of a need for independence, of a distrust toward unity. Those who are with us preserve their freedom.”

What is sacrificed in this dedication to individual expression, however, is the communicative function of art. Communication requires a shared system (a language, whether verbal, visual, or otherwise), and at least an assumption of shared concepts or emotions that can be conveyed through that system. Both of these requirements imply a sacrifice of radical individualism, so Tzara freely jettisons them: “Art is a private affair, artists produce it for themselves … When a writer or artist is praised by the newspapers, it is a proof of the intelligibility of their work: wretched lining of a coat for public use.” Dada should be unintelligible: “What we need is works that are strong straight precise and forever beyond understanding.” The unintelligibility of Dada art becomes proof of its author’s freedom from any shared language, truths, or values.

In its unintelligibility, offensiveness, and contradictions, Dada reflects the fundamental absurdity of life itself. The manifesto concludes: “Dada Dada Dada, a roaring of tense colors, and interlacing of opposites and of all contradictions, grotesques, inconsistencies: LIFE.” Dada is nonsense, but very carefully produced nonsense, targeted at very specific effects: to mirror the senselessness of the universe, to shake the reader/viewer out of their seductive but false systems of belief, and to encourage us to dance to our own personal boomboom.

Notes:

- Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918, as published in Dada vol. 3 (December 1918), n.p. The English translation throughout this essay is based on the University of Pennsylvania version, but has been occasionally modified for clarity using the original French version.

Additional resources:

Dada Pataphysics

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

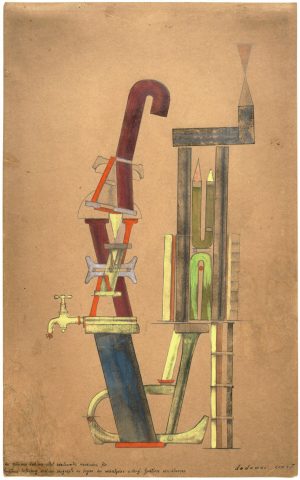

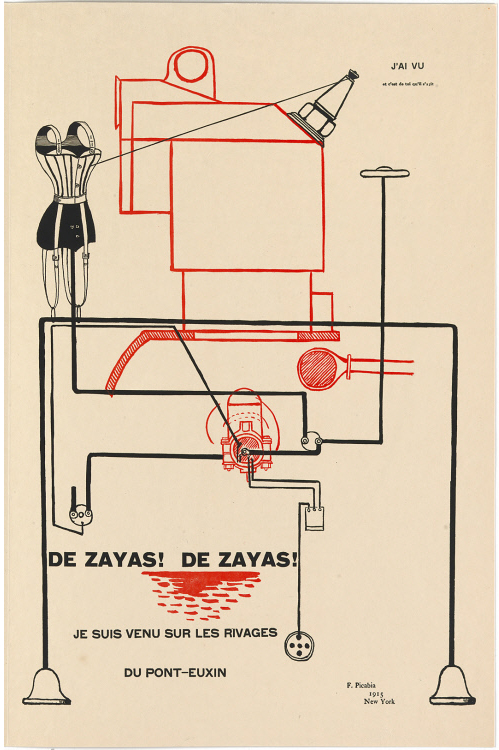

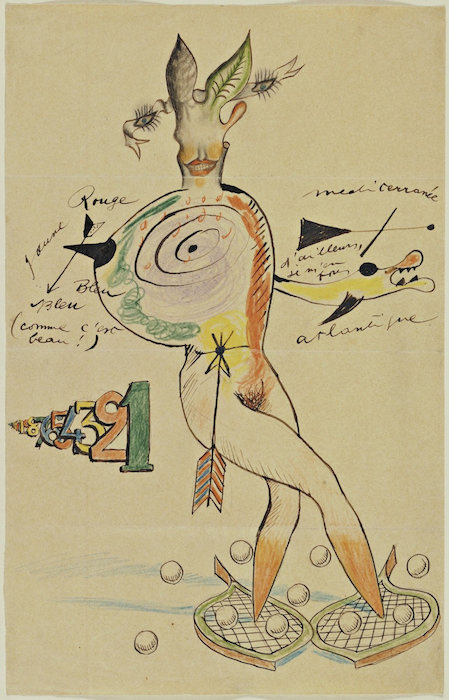

Careful inspection reveals this line drawing to be based on an electric diagram of an automobile, with two headlights at the bottom corners and a spark plug just right of center at the top. There are a number of schematic electro-mechanical components and wiring that attaches to the crotch and left breast of an empty woman’s corset. Nothing in the diagram or the text explains how this is a portrait of the Mexican writer and caricaturist Marius de Zayas, as the title indicates. It is one of many works by Picabia and other Dada artists that refer to modern science, engineering, and technology, often in bewilderingly nonsensical ways. What is this about? Why do science and technology feature so prominently in Dada works, and why are they treated so absurdly?

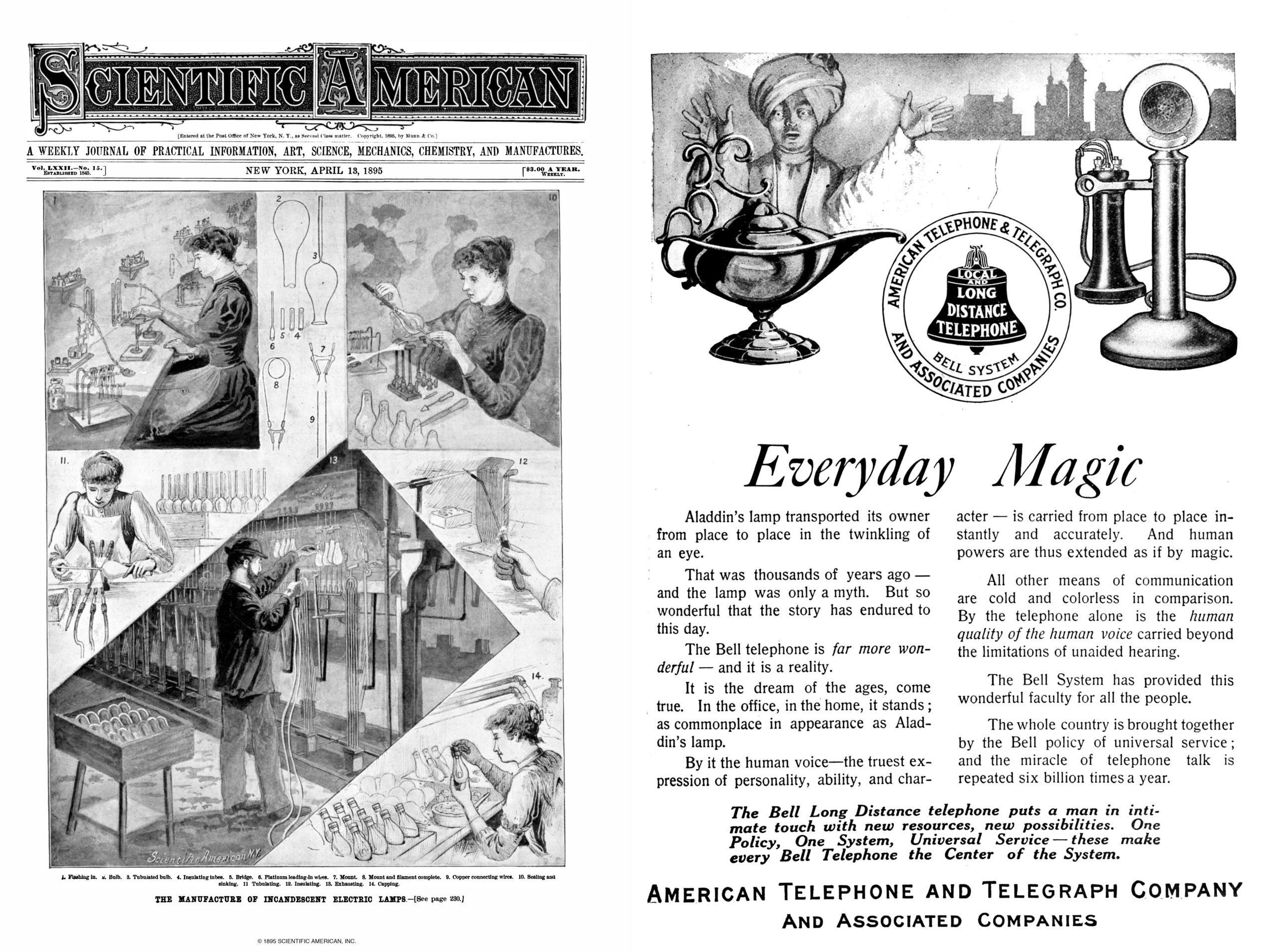

A machine age utopia

The first two decades of the 20th century witnessed the increasing presence of machines in everyday middle-class life, including telephones, automobiles, phonographs, typewriters, electric washing machines, and portable cameras. Public awareness of scientific discoveries and technological breakthroughs was also fueled by regular newspaper accounts of airplanes, radio waves, x-rays, and relativity.

Descriptions of scientific discoveries and advertisements for new technology tended to tout them in utopian terms — as solving longstanding problems and advancing wealth, leisure, and public welfare. In the early decades of the 20th century, modern artists such as Fernand Léger and Robert Delaunay celebrated the machine age both directly in their subject matter, and indirectly by choosing a hard-edged, geometric, rationalized style that mimicked machine-made products.

Against rational systems

In part, the Dadaists presented a scientific and mechanized vision of the world and humankind as an antithesis to expressionist artists, such as the Blaue Reiter group, who emphasized humankind’s spirituality. German Dadaists in particular adopted a materialist view of nature and human history that aligned with the political philosophy of Karl Marx and Communism. However, the Dadaists were also suspicious of the new science and technology for several reasons. Their response to the destructive use of technology during World War I is discussed in the essay Dada Politics. More generally, the Dadaists rejected all rational systems and utopian fantasies as part of their embrace of absurdism. Dadaists mocked all the ways that humankind has tried to find sense and purpose in what they saw as a senseless universe and purposeless existence.

For example, Three Standard Stoppages by French Dadaist Marcel Duchamp parodies the metric system, an attempt to advance scientific knowledge, engineering, and trade by standardizing units of measure. In 1799, France was the first country to adopt the metric system, when the meter was defined as one ten-millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole on a meridian passing through Paris.

Duchamp created his own parodic metric system(s) by dropping three meter-long lengths of string from a height of one meter onto a horizontal plane, allowing each to twist “as it pleases,” and then tracing their lines to make three wooden prototype “rulers,” which were placed in a special case. These rulers can be used both for measurement (although all three differ in length), and as straightedges (although all three have different curving profiles). Needless to say, any scientific or engineering project that depended on Duchamp’s system would be sabotaged from the start.

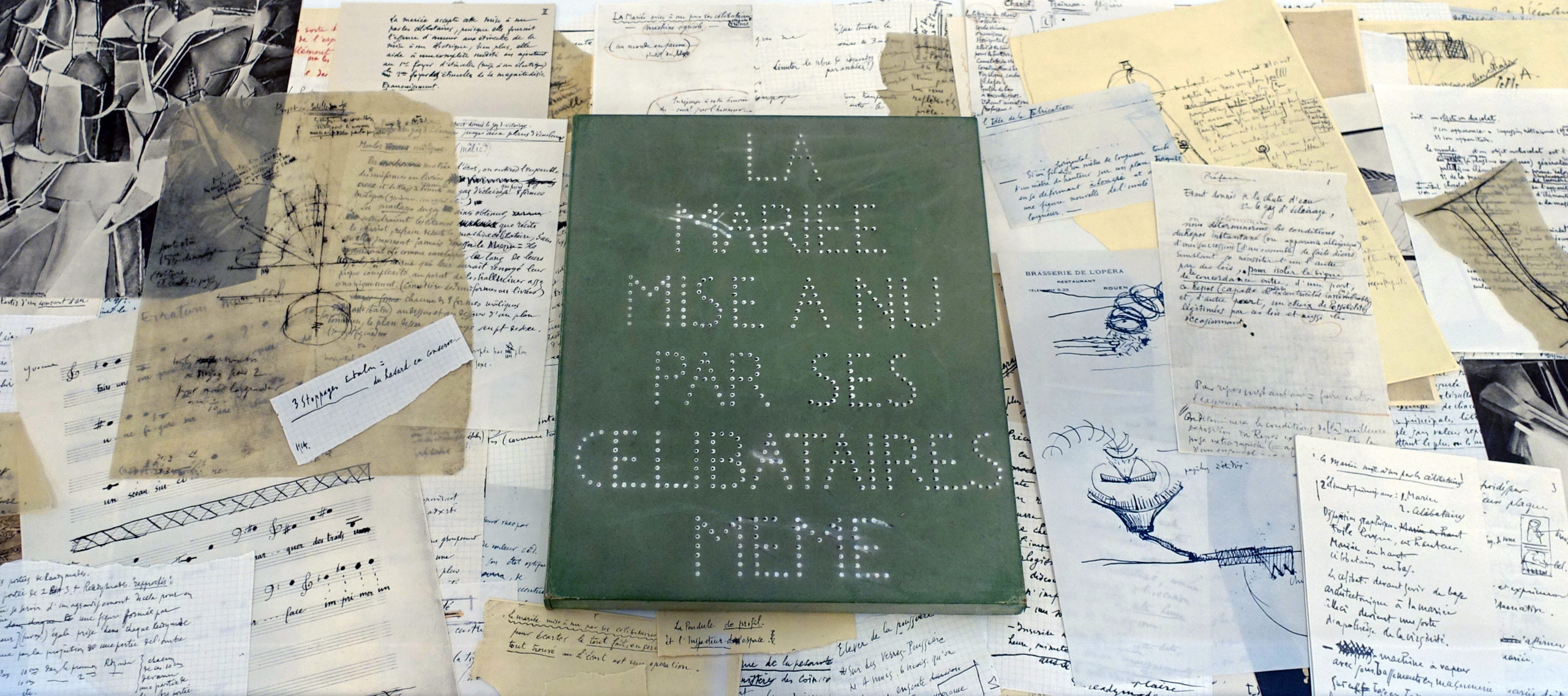

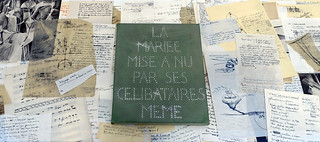

Duchamp used his new metric system to create one of the most absurd “engineering” projects of all time, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (1915-23), often called the Large Glass. Essentially a design for a machine to help the nine bachelors in the lower register make love to the bride above, the elaborate physics and engineering of the contraption were described in hundreds of notes that the artist wrote on scrap paper over many years. Many are written in complex pseudo-technical language, such as:

The bride, at her base, is a reservoir of love gasoline. (or timid power). This timid-power, distributed to the motor with quite feeble cylinders, in contact with the sparks of her constant life (desire-magneto) explodes and makes this virgin blossom who has attained her desire.Translated in Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, eds., The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (New York, 1973), pp. 43-4.

These bewildering notes were tossed into a box in no particular order, and in later years, Duchamp meticulously reproduced them in limited-edition box sets, thereby increasing the absurdity of the project.

Pataphysics

Duchamp was inspired by the absurdist writings of French Symbolist author Alfred Jarry, who coined the term “pataphysics” to refer to a “science of imaginary solutions” that would “examine the laws governing exceptions” in his posthumously published novel The Exploits and Opinions of Dr Faustroll, Pataphysician (1914).\(^{[1]}\) The term pataphysics is currently used to refer to works that imitate the language and imagery of science and technology, but upend them and make them dysfunctional or absurd.

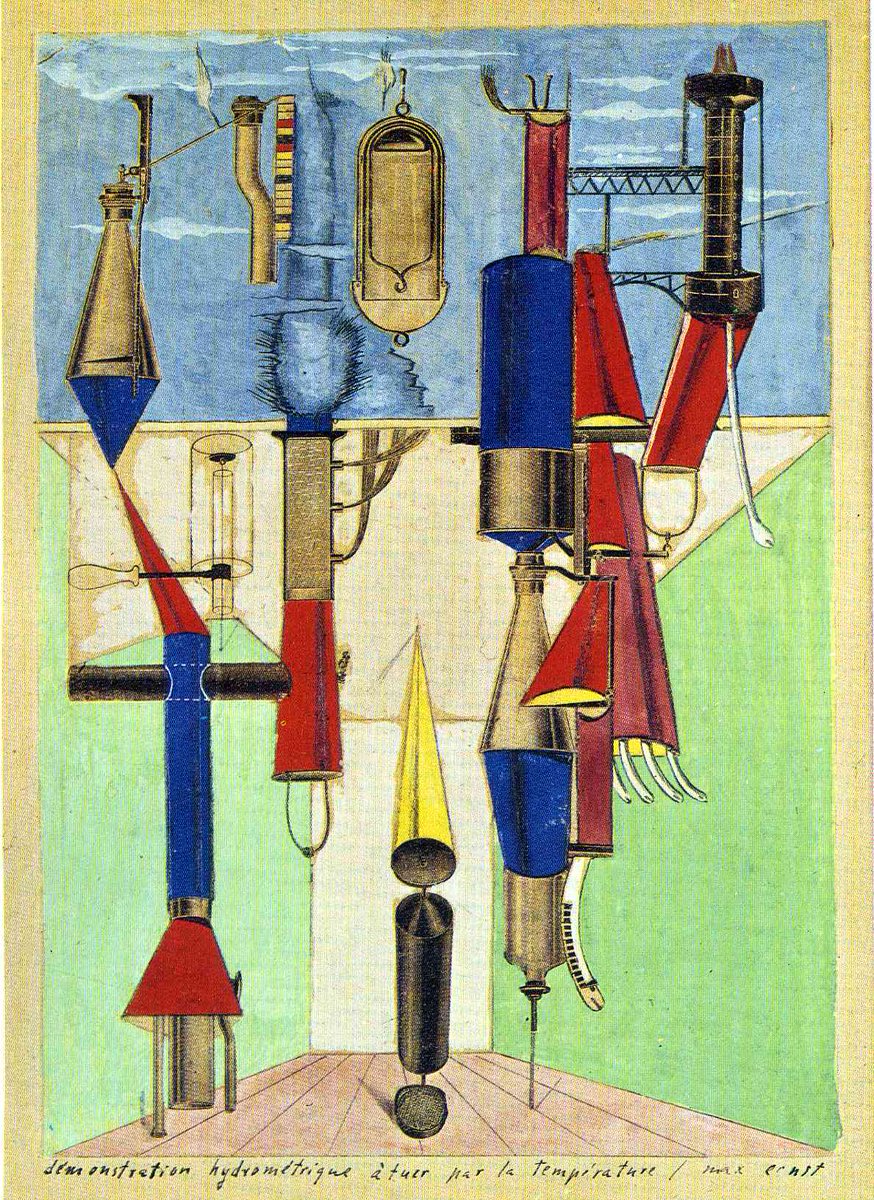

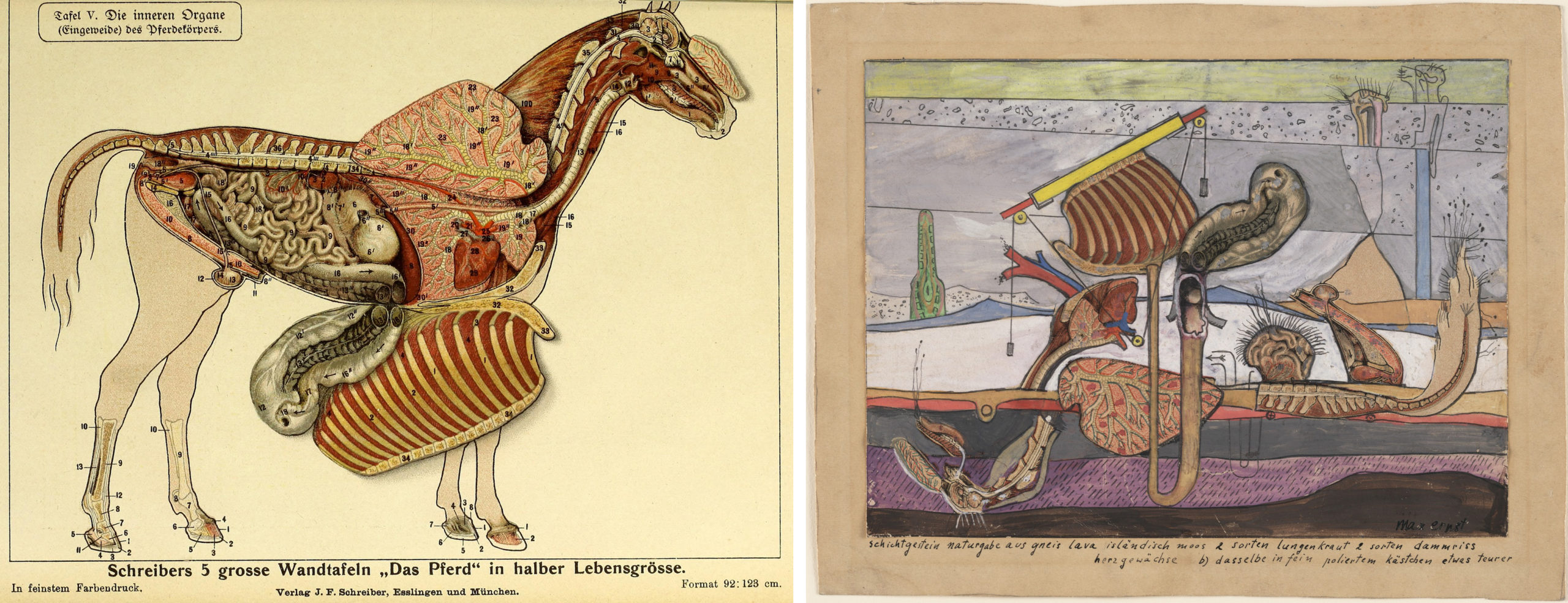

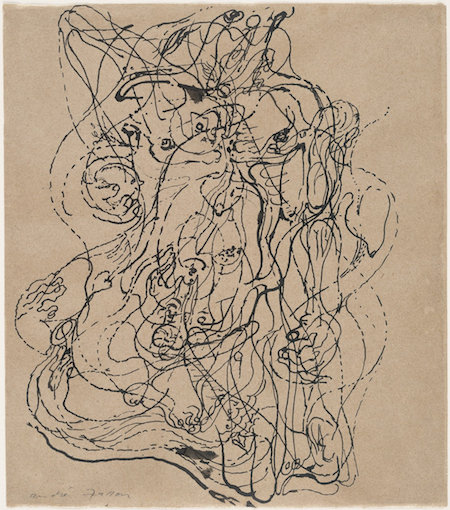

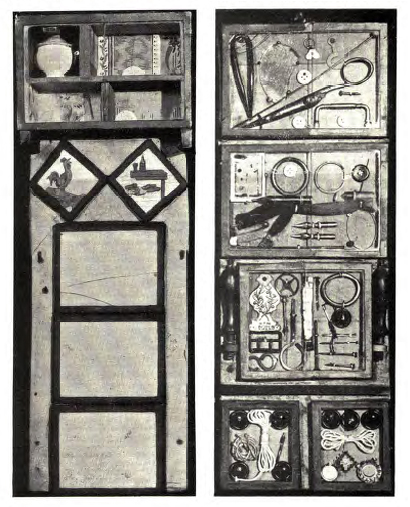

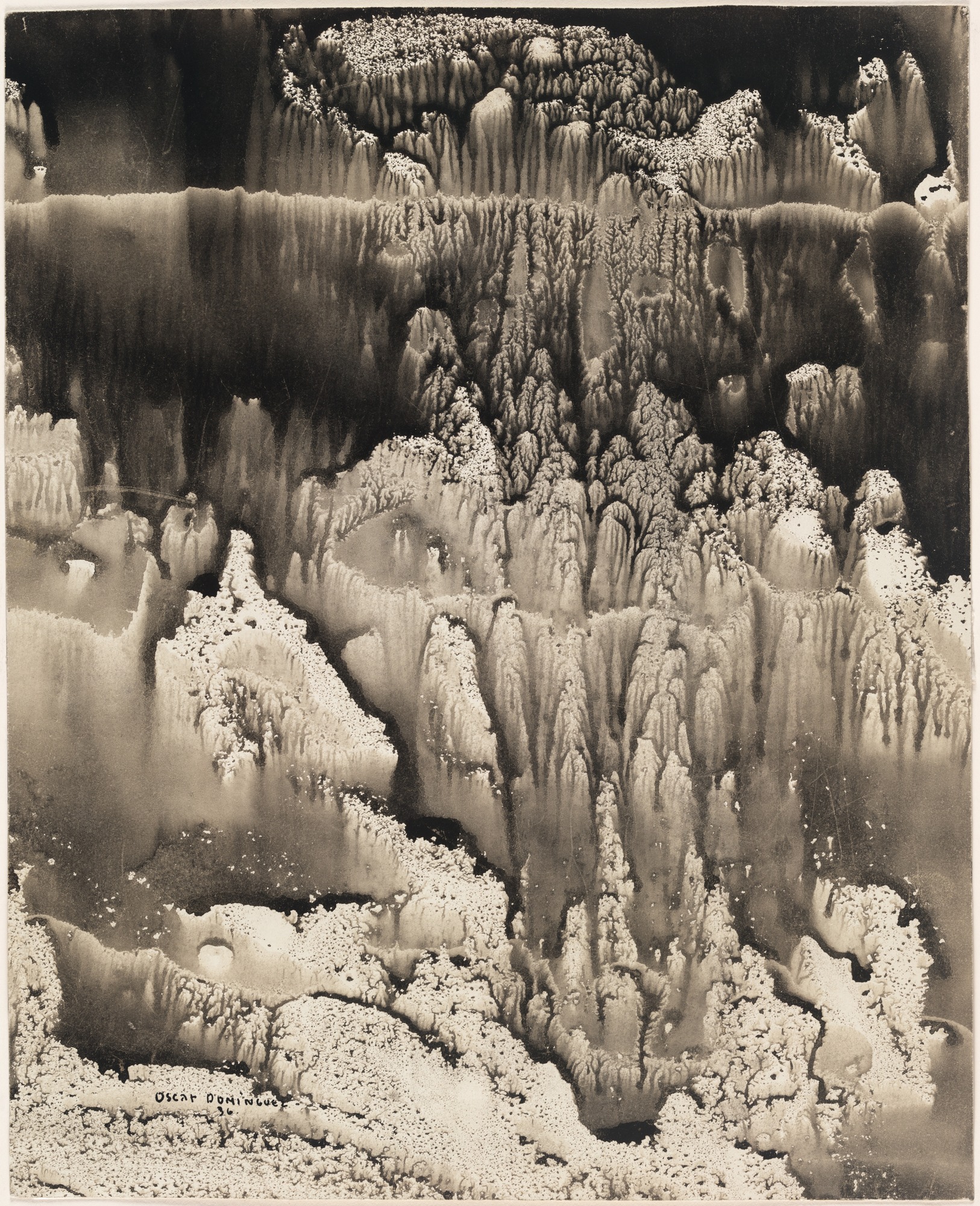

The Dada artist Max Ernst was also inspired by Jarry, and claimed that his works could only be understood by “poets, pataphysicians, and a few illiterates.”\(^{[2]}\) Among his absurd pataphysical creations was a set of works made by using a catalog of scientific teaching materials called Bibliotheca Paedagogica.

In this piece, for example, an illustration of the inner organs of a horse is flipped upside-down and selectively covered with opaque paints until it becomes a diagram of geological strata where bizarre fossilized life-forms and a machine with pulleys await discovery. Ernst’s title, written longhand below, reinforces the pseudo-scientific qualities of the work in a characteristically absurd way: Stratified Rocks, Nature’s Gift of Gneiss Lava Iceland Moss 2 kinds of lungwort 2 kinds of ruptures of the perinaeum growths of the heart b) the same thing in a well-polished little box somewhat more expensive.

A “machinomorphic” ideal

While many Dada misappropriations of contemporary science and technology are nonsensical, others seem calculated to raise philosophical questions about human nature and ethics. This is especially true of works that use the common Dada tactic of substituting machines for humans, either in whole or in part.

Human beings are commonly considered superior to machines because of our ability to feel, to act with free will, and to behave ethically — all of which are thrown into question when technology replaces humanity. As photographer Paul Haviland put it in a 1915 essay:

We are living in the age of the machine. Man made the machine in his own image. She has limbs which act; lungs which breathe; a heart which beats; a nervous system through which runs electricity. The phonograph is the image of his voice; the camera the image of his eye … After making the machine in his own image he has made his human ideal machinomorphic.Paul B. Haviland, statement in 291, nos. 7-8 (September-October 1915), n.p.

The same year, Francis Picabia made a portrait of Haviland as a lamp with its plug-less electric cord wrapped impotently around it. German Dadaist Raoul Hausmann’s Mechanical Head seems to realize this human-machine “cyborg” ideal, while at the same time underscoring the dangers of idealizing machines and using them to replace humanity.

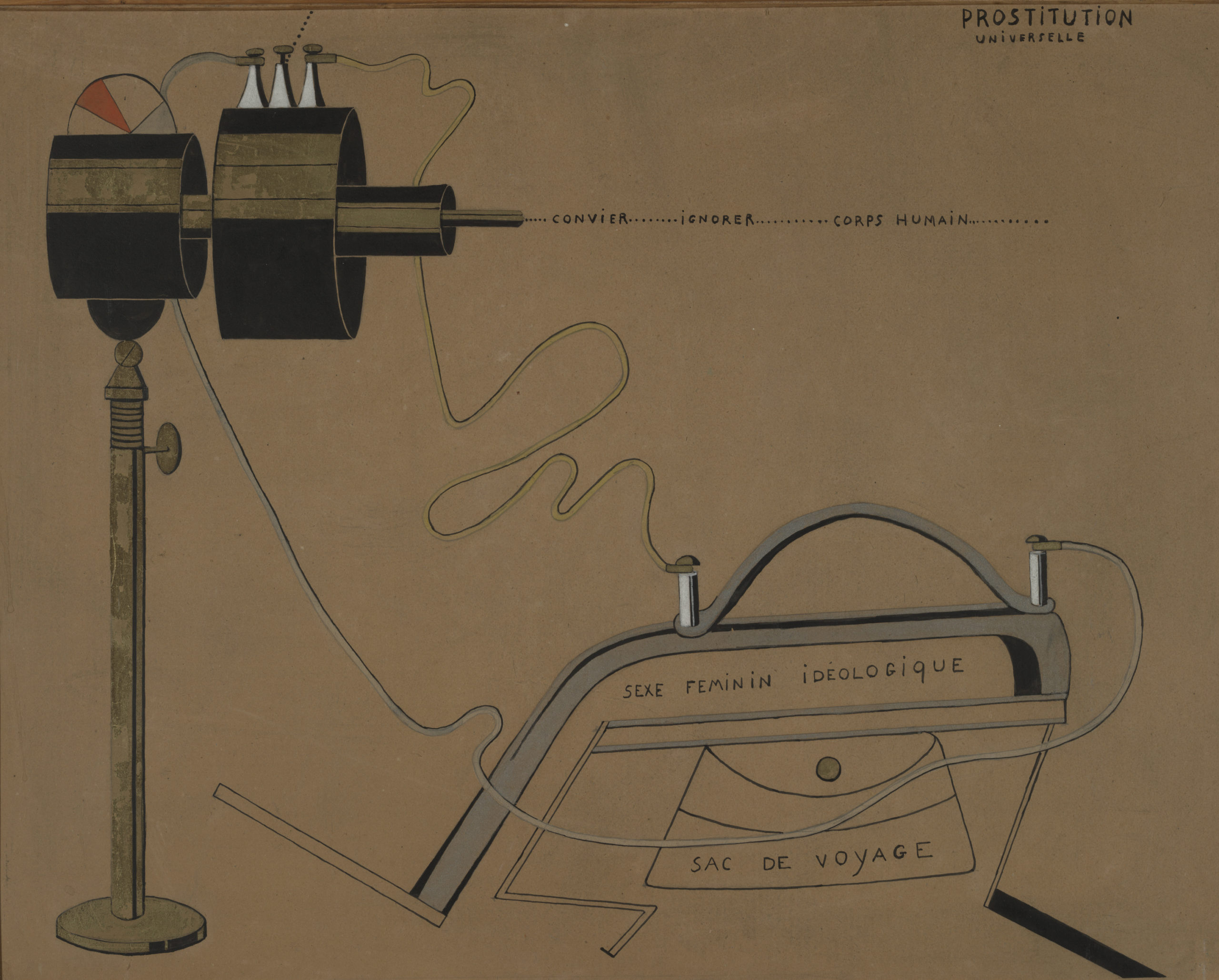

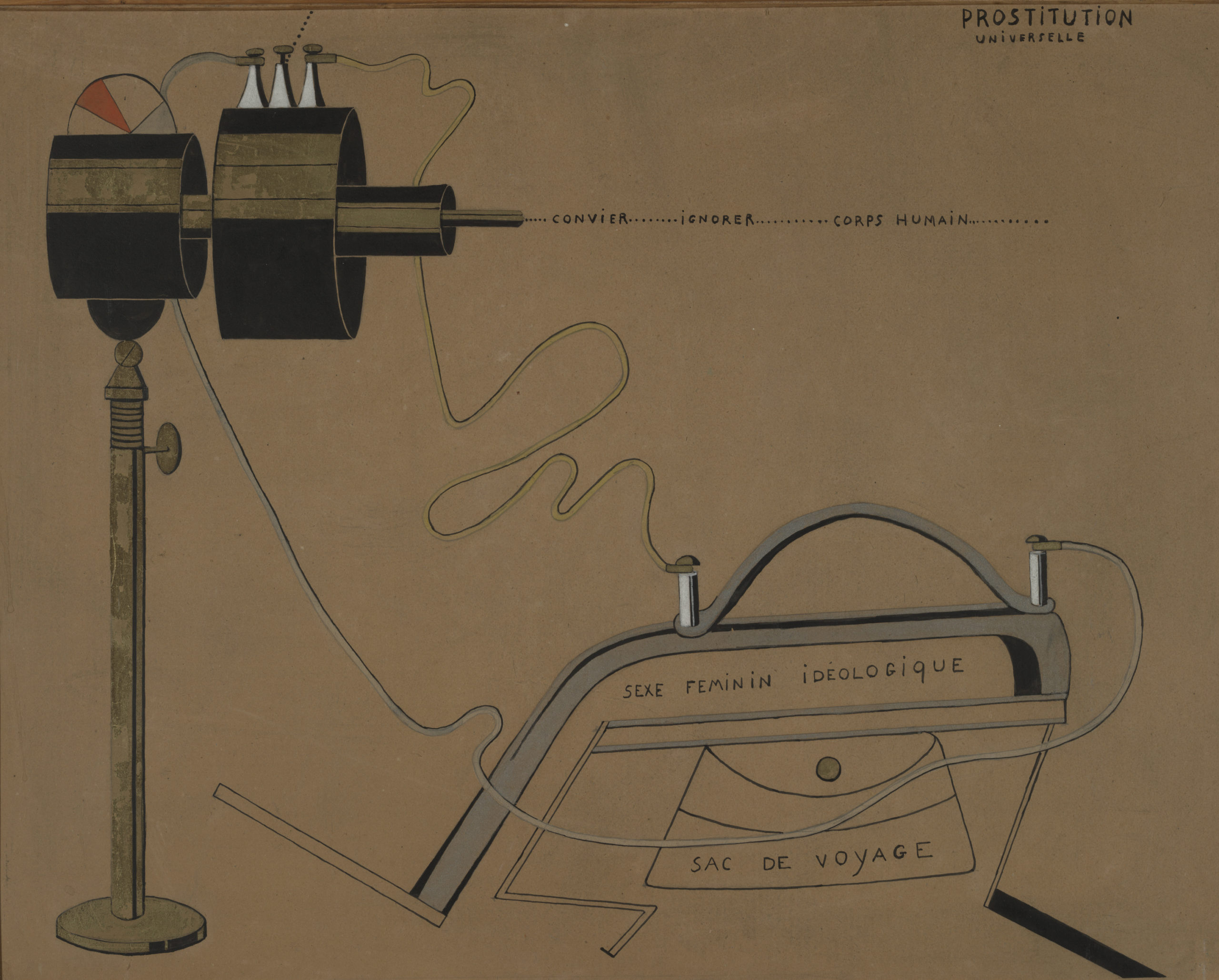

Sex machine

Dada artists frequently conflated technology and sexuality, creating an uncomfortable disjunction between the cold, geometric impersonality of machines, and our expectations of emotionally-engaged, warm, organic intimacy. This is evident in Duchamp’s Bride Stripped Bare and Picabia’s Portrait of Marius de Zayas discussed above, and even more blatantly in Picabia’s Universal Prostitution, where an upright, phallic electrical machine spews provocative words (“to invite … to ignore … human body”) over the kneeling mechanical form to which it is wired. The lower form is labeled “ideological feminine sex” with her “travel bag,” suggesting an absurd commentary on the relationship between the genders.

In all of his works illustrated on this page, Picabia’s style reinforces the machine-versus-human contrast. Where we expect the original, expressive, and autographic mark of the artist, Picabia employs the inexpressive linear anonymity of an engineering diagram.

The Dada interest in science and technology was not only highly topical in the early twentieth century during a burgeoning “machine age,” but it also posed wider, philosophical questions about what happens when machinery replaces humanity.

Notes:

- Alfred Jarry, Exploits & Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (Boston, 1996), ), pp. 21-22.

- Max Ernst, La Nudité de la femme est plus sage que l’enseignement du philosophe (Paris, 1959), as translated in Max Ernst: A Retrospective (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1975), p. 14.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Dada Politics

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

A sign reading “Dada ist politisch” (Dada is political) is visible on the right side of this photo of the opening of the 1920 First International Dada Fair in Berlin. The German Dadaists’ explicit engagement with politics marks a notable change from Zurich Dada, which, while iconoclastic, was rarely overtly political. This is partly because Switzerland was neutral during World War I, and provided something of an escape for the artists who gathered there. The founder of Zurich Dada, Hugo Ball, once described Switzerland as “a birdcage, surrounded by roaring lions.”\(^{[1]}\) When Dada spread to Germany following the end of World War I, it entered the lion’s den.

Social and economic crisis

Germany was in social, political, and economic chaos after the war. Its industrial base had been decimated, and there was a struggle for political power between the right-wing Social Democrats and the left-wing Communist Party. The Spartacist Uprising, a general strike and armed insurrection by the Communists in 1919, was met with brutal repression and the extra-judicial killing of its leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Following the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1919, a new government known as the Weimar Republic was formed by the Social Democrats. The new government was immediately beset by economic difficulties that included massive war debts and the punitive reparations set by the Treaty of Versailles. To pay off its debts the government simply printed more money, which led to hyperinflation. By the end of 1922, a loaf of bread cost 200 billion Deutschmarks. Most of the German Dadaists were sympathetic to the Communist party and strongly critical of the Weimar government and its policies.

Against bourgeois capitalism

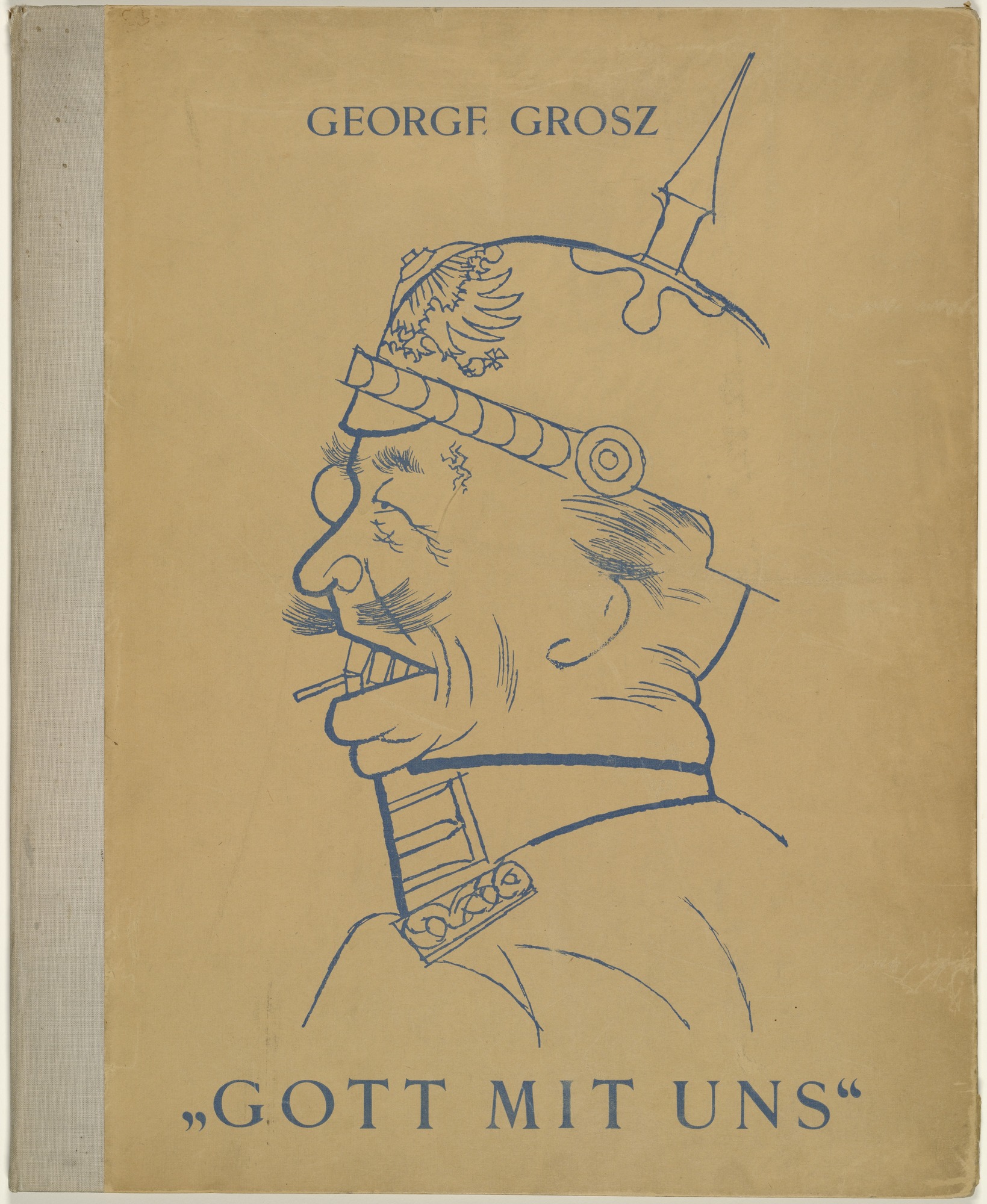

George Grosz, whose painting A Winter’s Tale (1917) is visible hanging above the “Dada ist politisch” sign, was born Georg Groß, but changed the spelling to “de-Germanize” his name as a protest against German nationalism. He was arrested during the Spartacist Uprising, and was a member of the Communist Party until 1923.

A portfolio of Grosz’s iconoclastic prints was on sale at the Dada Fair. The title “Gott mit uns” (God is with us), taken from the official slogan inscribed on the belt buckles of German army troops, is clearly mocked by the grotesque caricatures of soldiers and officers in the portfolio. Grosz and his publisher were fined for defamation of the military, and all unsold copies of the portfolio were destroyed.

Unrepentant, Grosz continued to make prints critical of the ruling classes. His photo-lithograph Dawn shows two simultaneous early morning scenes. On top, members of the working class, tools and lunch pails in hand, trudge to work at the factory, while in the scene below, the wealthy continue to enjoy their previous evening’s debauchery. The workers are mostly thin and ragged, while the wealthy bourgeois men are caricatured as fat and dissipated figures clutching their cocktails and prostitutes.

War technologies

Another major target of Dada scorn was science and technology; this was part of a broad strategy to discredit rational thought and utopian projects. The Dada mistrust of technology also had roots in its destructive use during World War I.

The Great War, as it it was then known, was largely fought by armies hunkered down in vast networks of defensive trenches. Offensive sorties resulted in massive casualties, as charges were met by a hail of bullets from recently-invented machine guns. Armored vehicles were invented to protect troops during charges, and continuous “caterpillar” tracks on a rhomboid frame helped these early tanks navigate the deeply entrenched terrain. Chemical weapons delivered by artillery, such as chlorine gas and mustard gas, were also brutally effective against massed troops, necessitating the use of gas masks and protective clothing. War photographs suggest not only the destructiveness, but also the dehumanizing effect of these new military technologies.

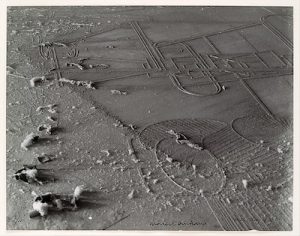

The Communist-influenced Dadaists saw the roots of this destruction not just in the technology itself, but in what later became known as the “Military-Industrial Complex,” the factory owners and financiers who profited from weapons manufacture. In her collage Hochfinanz (High Finance), Hannah Höch shows two middle-class figures with outsized heads dominating an aerial view of Wroclaw, Prussia (now in Poland). Surrounding them are images of weaponry, machinery, and mass production: two shotguns, a factory, piston rods, a threaded bolt, the red-white-and-black Imperial German flag, and a military truck driving along a rubber tire. One of the two figures is British scientist Sir John Herschel (perhaps in reference to the contribution of scientists to the invention of war technologies), but the title High Finance suggests that the two well-dressed old men are bankers implicated in both the destructive war technologies and the exploitative practices of early-twentieth century capitalism.

War casualties

Also visible in the Dada Fair photograph are two works that refer to another lingering effect of the war: the common sight of soldiers returning with disfiguring injuries, amputated limbs, and artificial body parts. On the right edge of the photo is a sculpture of a man by George Grosz and John Heartfield entitled Middle-class Philistine Heartfield Gone Mad. The torso is a tailor’s dummy decorated with symbols of war (a revolver, an iron cross, an insignia for the Black Eagle Order), while much of the rest of the body is made of machine parts: a metal pipe for a leg, a lightbulb for a head, and dental prostheses for genitals. The figure also wears a dehumanizing number for identification. The assemblage simultaneously suggests a wounded soldier with multiple prostheses, and a cyborg whose infatuation with technology has overwhelmed its humanity.

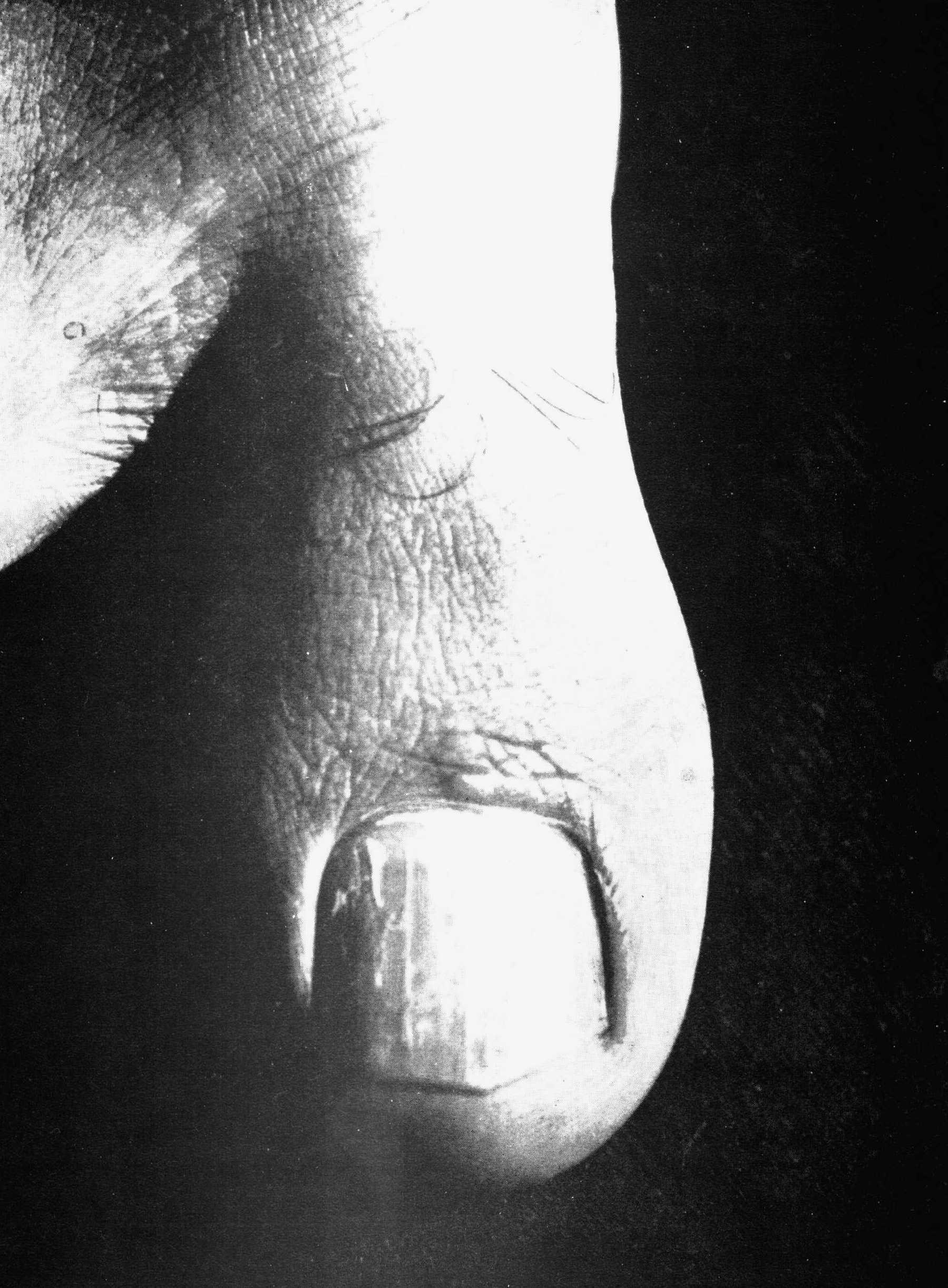

On the left of the Dada Fair photograph is the painting War Cripples, or 45% Fit for Duty, by Otto Dix, who served as a machine gunner in the Battle of the Somme, during which one million men were killed or wounded. Dix’s original painting was destroyed, but a contemporary print shows how it called attention to the war wounded. Although they are attired in the splendor of their full-dress uniforms, large portions of the soldiers’ bodies have been replaced by prosthetics, and what at first may appear to be “modernist” distortions of their faces are not. The man at the far left has a permanently staring glass eye, and his jaw has been replaced by a crude early attempt at plastic surgery that is only slightly less disturbing than the mangled face of the man at the far right. To his left, permanent tremors afflict a man with “shell shock” (now known as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), and next to him a quadriplegic man is being wheeled past a shoe store he will never need to visit. It is hard to overstate the contrast between this image and traditional, heroic depictions of soldiers.

Images such as these show how the Dadaists’ mistrust of authority, technology, and nationalism, combined with their willingness to shock and offend, were effective in creating devastating social and political criticism in postwar Germany.

Notes:

- Hugo Ball, Flight out of Time: A Dada Diary, ed. John Elderfield and trans. by Ann Raimes (Berkeley, L.A. and London, 1996), p. 34.

Additional resources:

Read more about Otto Dix at MoMA

Read more about George Grosz at MoMA

An online catalogue of works by John Heartfield at the Akademie der Künste

Dada Collage

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

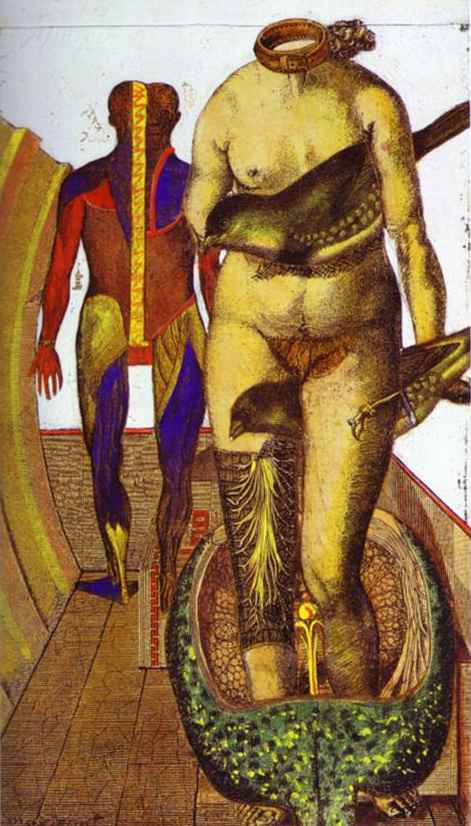

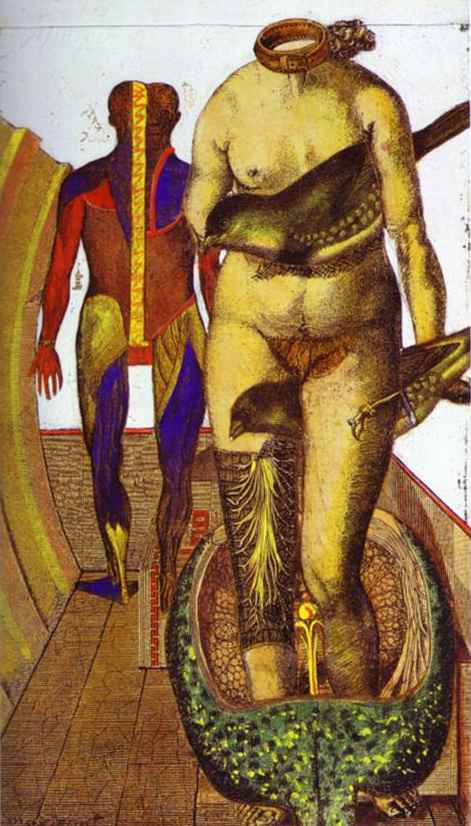

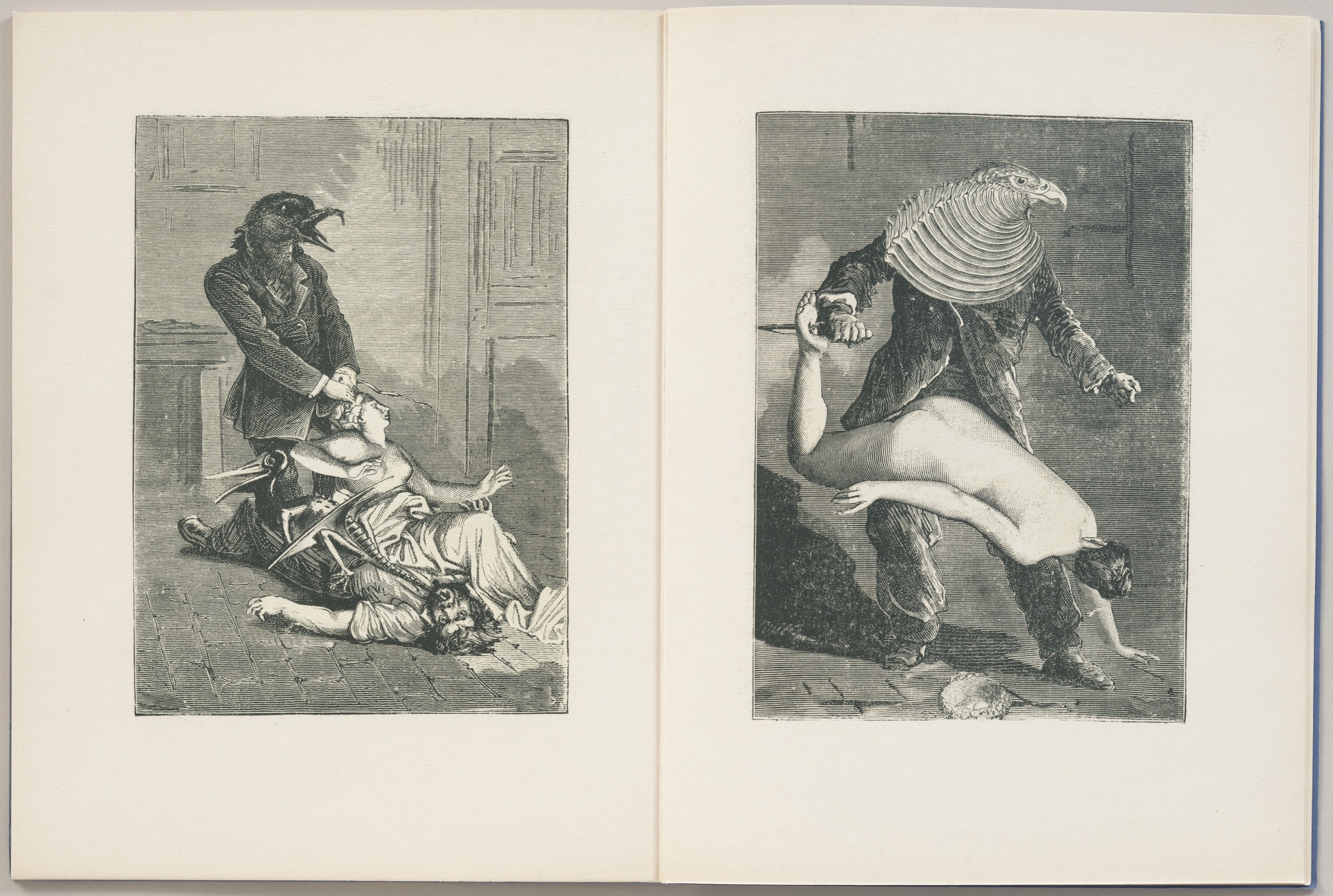

A nude woman stands in the foreground, a collar around her headless neck and birds tucked between her legs and under her arm. Her right thigh has been skinned to reveal a network of root-like nerves or blood vessels, and she stands knee-deep in what appears to be a cut-open internal organ or organism. Slightly behind her in the shallow space stands a fully-flayed figure that has been sliced vertically in two so we see it half from behind and half from the front

Although some attempt has been made to unify the space by enclosing the figures in a room defined by linear perspective, this work is clearly a collage made up of elements cut from a variety of sources. The foreground woman is Eve from Albrecht Dürer’s Adam and Eve, the background figure is an anatomical illustration, and the birds were presumably sourced from an ornithological guide. The technique of collage, long used in a domestic and craft context to make samplers, scrap-books, and greeting cards, had recently been ushered into the world of fine art by Braque and Picasso’s Synthetic Cubist experiments.

The Cubists used collage to further their explorations of the ambiguities of space and representation, but the Dadaists saw in it the potential to advance their absurdist philosophy and political activism.

Inherently Dada

There is something inherently Dada about the technique of collage. Its use of prefabricated or readymade materials negates the importance of artistic skill, and the fact that collage is frequently sourced from mass-produced advertising and journalism collapses boundaries between “high” and “low” culture. Also, the act of making a collage is literally iconoclastic (Greek for “image-breaking”). Cutting up source material implies a rejection of its world-view, a disruption of the way that newspaper, that scientific text, or that advertisement organizes information, and a refusal of the ideas or directives it was intended to convey. Finally, the recombination of these elements gives free play to the artist’s desire to re-shape the world, which for the Dadaists often resulted in images that range from bizarrely humorous to downright disturbing.

Ernst’s The Word, for example, assaults numerous targets of Dada scorn. Much of the source material appears to be scientific in nature, continuing a broad Dada offensive against science and technology. The incorporation of Dürer’s engraving of Adam and Eve mixes religion with science as well as high art with “mere” illustration. The fact that Dürer’s print uses animal symbolism suggests, but does not spell out, a symbolic meaning for the birds, which had an ambiguous multivalence in Ernst’s art. Their placement here is unquestionably sexual, and Eve’s nudity and the mutilation of both her body and that of the background figure (Adam?) creates uncomfortable overtones of sexual violence. Altogether, the image is absurd, humorous, anti-conventional, and disturbing, all characteristic qualities of Dada.

Photomontage

Dadaists invented a form of collage known as photomontage, which incorporates photographs, sometimes along with other collaged and painted elements. The reputation of photography as a factual record of the world implies a truth-to-reality that can make the absurdity of Dada photomontages additionally disturbing. Many photomontages were sourced from advertisements and journalism. The products and fashions in them appear dated today, but were insistently topical and relevant at the time, and helped Dada to mount an offensive against contemporary social, political, and commercial culture.

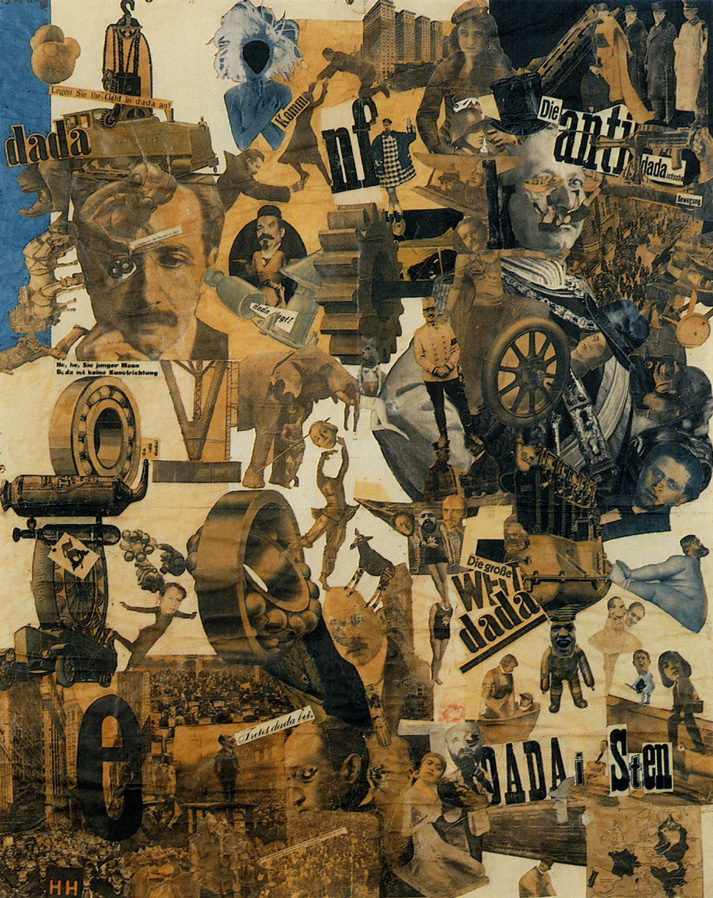

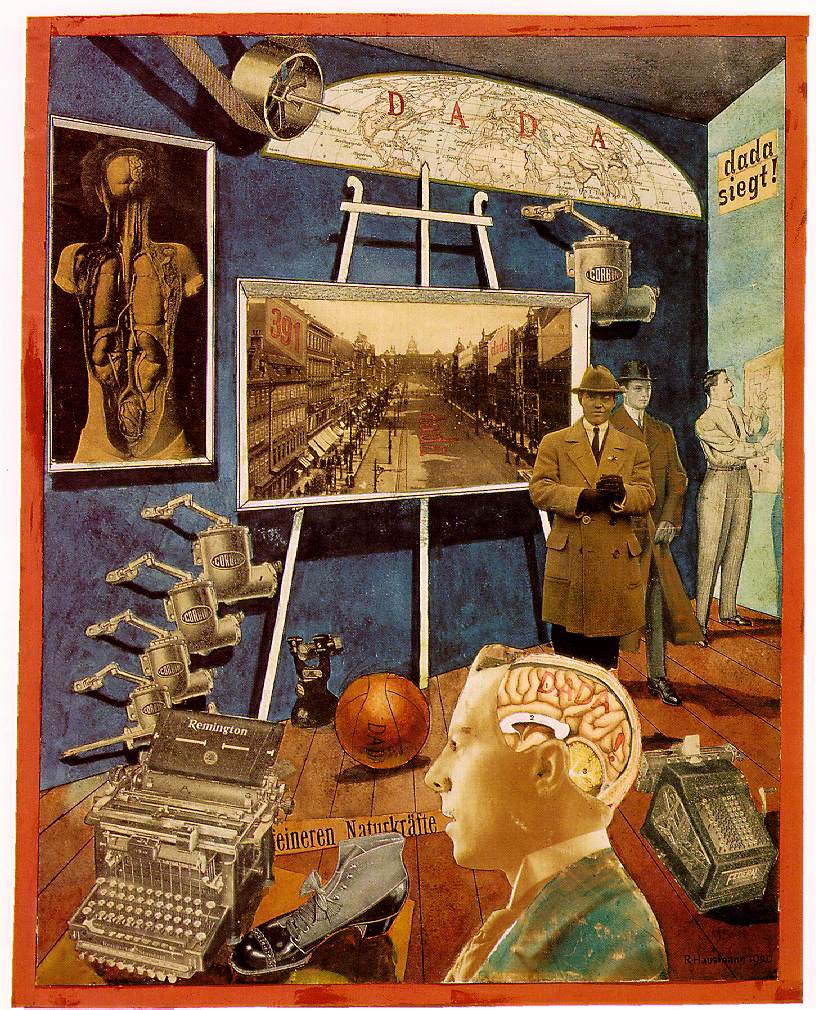

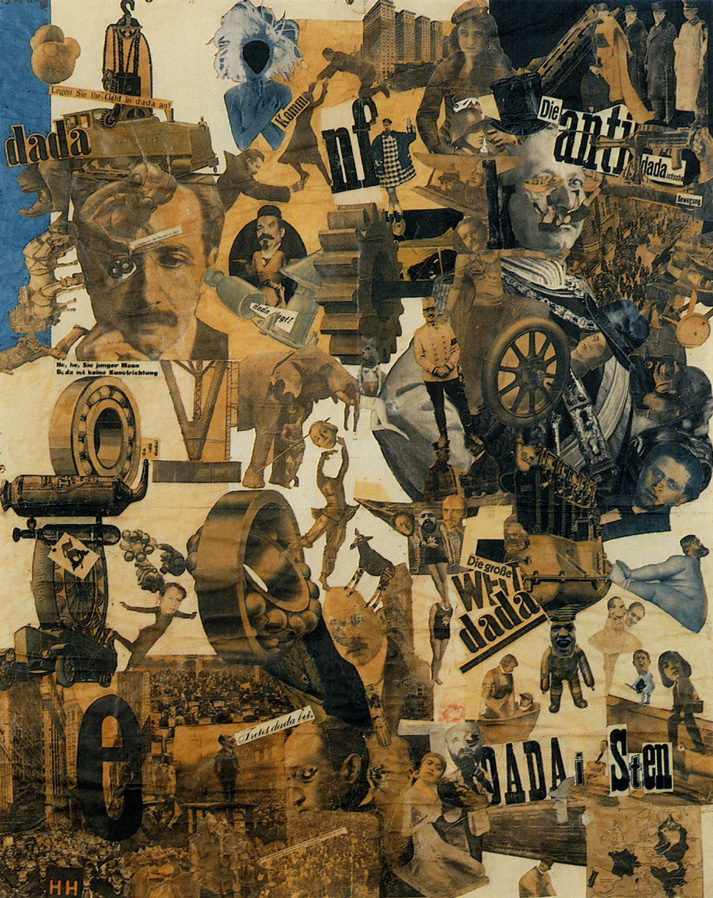

Raoul Hausmann’s photomontage A Bourgeois Precision Brain Incites a World Movement (often called Dada siegt, or “Dada triumphs”) shows an interior cluttered with various objects suggestive of the title: a partial map of the world, a diagram of a brain, and three well-dressed middle-class men, including Hausmann himself. “Precision” is suggested by all of the scientific and machine references, including a typewriter and adding machine in the foreground, as well as another anatomical diagram hanging on the back wall. A pulley and drive belt in the upper left, along with a series of Corbin brand automatic door-closers below, refer to industrial and assembly-line production techniques. The “world movement” of the title is, however, not the orderly, precision phenomenon suggested by these objects. It is instead the unruly disorder of Dada, which we see emblazoned across the map, inscribed on the brain, and written on the street in the background photograph of the Wenzelsplatz in Prague.

Political critique

Hausmann claimed to have appropriated the idea of photomontage from a traditional practice among German military families, who would paste a photograph of their enlisted son’s face over the head of a lithograph of a generic soldier. This anecdote suggests a political dimension to the technique of photomontage, although Dada collages generally challenged militarism and patriotism. Post-World War I Germany was a social and economic disaster. In addition to the destruction of a large part of its industrial base during the war, punitive reparations following Germany’s defeat led to rampant inflation. The generally left-leaning German Dadaists were much more politically active than their counterparts in Zurich, Paris, or New York City, and frequently used art as a form of direct social and political critique.

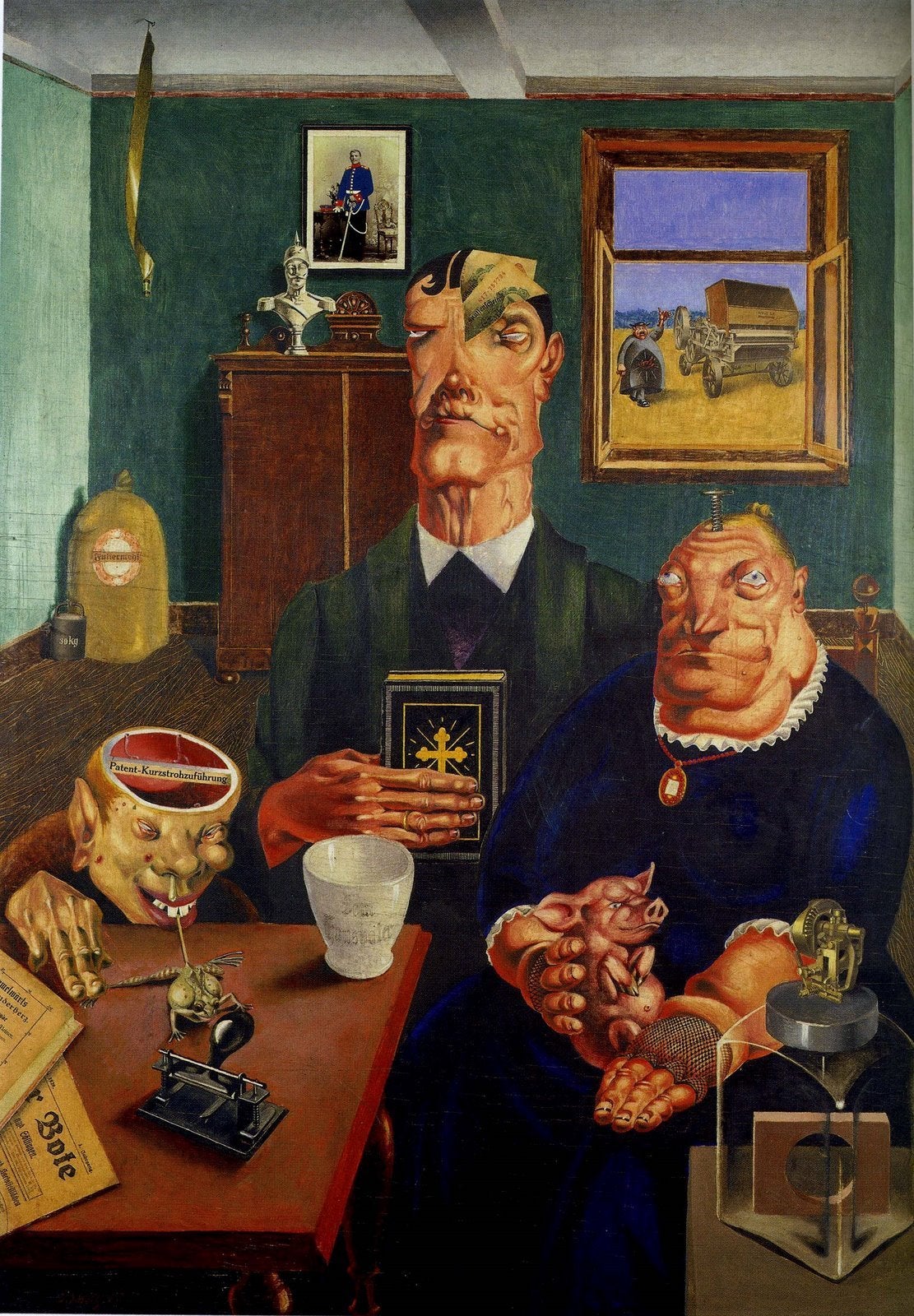

Georg Scholz combined collage and photomontage with traditional oil on panel in Bauernbild (Farmer Picture), a scathing satire of the greed and hypocrisy of the large-scale industrial farmers that were replacing traditional small farms. The grotesquely caricatured couple sit proudly in the foreground. He clutches a bible, but his partially sliced open head reveals his true motivation, money. His wife, a nail through her forehead, proudly displays one of her pig-like offspring, while his snotty-nosed and pimple-faced brother is tormenting a toad, a farm-machine patent the only thing in his empty head. Various mechanical devices in the room and a threshing machine out the window demonstrate the family’s devotion to industrialization, while on the back wall, portraits of the recently deposed Kaiser Wilhelm II and another son in uniform demonstrate their patriotic support of the government and the war.

The roots of collage

With self-conscious irony, Hannah Höch returned collage to its roots as a traditionally female domestic art form. The long title of her photomontage Cut with a Kitchen-Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany suggests how her feminine tool — the kitchen knife that is ostensibly creating the collage — is being used to cut through the (implied masculine) bloated and self-indulgent political class of the time. (Weimar, Germany was where the first democratic constitution of Germany was signed after WWI, giving the name Weimar Republic to the inter-war government.)

Scattered throughout the collage are photographs of German political figures such as the recently-deposed Kaiser Wilhelm II (upper right) and current president Friedrich Ebert (upper center) surrounded by images of gears, ball bearings, soldiers, and other emblems of industrial and military power. Text cut-outs such as “Join Dada” and “invest your money in Dada” exhort us to participate in the mass resistance, represented by crowds of demonstrators in the lower left, along with Communist leaders including Vladimir Lenin and Karl Marx (center right), and recently-assassinated German Communist Party leader Karl Liebknecht (lower left). Interspersed throughout are signs of growing female empowerment. A map in the lower right highlights European countries that had recently given women voting rights, and at the center German Expressionist artist Käthe Köllwitz’s head is juggled by a woman dancer, a common emblem of female freedom in Höch’s work.

The heterogeneity of the source material in all of these examples, along with the dizzying shifts of scale and perspective, makes viewing Dada collages an unsettling aesthetic experience. Because the use of prefabricated, mass-produced source material violates conventions of artistic skill and originality as well as aesthetic harmony, collage was in many ways a perfect medium for Dada iconoclasm and social protest.

Dada Readymades

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Although they were conceived more than a century ago, readymades continue to challenge and confound. The term was coined by Dada artist Marcel Duchamp to describe ordinary, prefabricated objects selected by an artist and presented as art. Sometimes the object is altered, such as by combining it with another object to make an “assisted readymade.’” The first readymade consisted of a bicycle wheel mounted upside-down on the seat of a stool. What are we to make of such an object? Why does it qualify as a work of art? Is any object a potential readymade? Can anyone make one?

For his most notorious readymade, Duchamp took an ordinary men’s urinal, flipped it ninety degrees, titled it Fountain, and submitted it to an art exhibition under the pseudonym “R. Mutt.” Although the exhibition was non-juried, meaning that it would theoretically accept any submitted work, Fountain was rejected, and Duchamp published a defense of it:

Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, and placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view — created a new thought for that object.

Marcel Duchamp (anonymously), “The Richard Mutt Case,” in The Blind Man, no. 2 (May 1917), n.p.

Duchamp here notes several points of intervention by the artist that make even a “pure” readymade like Fountain different from an ordinary object:

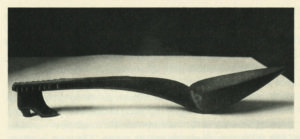

(1) The readymade is chosen by the artist. Different objects have different associations and significance; an airplane propeller signifies something different than a high-heeled shoe. Readymades do not display an artist’s technical skill, but a work of art based on choosing an object, rather than representing one, does not necessarily sacrifice a capacity for meaningful communication.

(2) The readymade is divorced from its ordinary context and use value, and re-presented in an art world context. This encourages us to encounter the object in a different way. A urinal encountered in a men’s restroom is a simple matter of utilitarian fact; one encountered in a gallery becomes a focus for observation, cogitation, discussion, appreciation, and/or denunciation.

(3) The readymade is sometimes given an unexpected title. This also encourages us to think about the object anew: Why is Duchamp’s urinal entitled “fountain”? What do urinals have in common with fountains? How are they different? Why is a fountain suitable for public display (and a common site for sculptural decoration), while a urinal is not?

Stupid as a painter

Duchamp insisted that these points of intervention serve to “create a new thought for that object,” signaling that the purpose of the readymade is fundamentally conceptual, not aesthetic or technical. Any objection that the object is not beautiful or did not require any skill to make misses the point.

In a 1946 interview, Duchamp objected to the common French expression, “stupid as a painter” — roughly an equivalent to the American “dumb as a box of rocks’” or British “thick as two planks.”\(^{[1]}\) He blamed the poor reputation of painters’ intelligence on the fact that art is so strongly associated with mere technical skill and/or sensual appeal — how well artists reproduce what they see or stimulate aesthetic pleasure. Readymades require neither technical skill nor formal sensitivity; the “art” is purely in the idea.

Unconventional and dysfunctional

Invented in the context of Dada, many early readymades seem to be direct challenges to social conventions. (For a brief explanation of the underlying philosophy of Dada, see Tristan Tzara’s Dada Manifesto)

For example, the American Dadaist Man Ray created an assisted readymade by welding a row of tacks to the bottom of a flatiron, an early form of clothes-press that was heated directly on a stove rather than by electricity. The result is worse than useless; it is actively counter-productive. An object intended to help keep clothes neat would instead reduce them to tatters. The title suggests a further assault on polite convention; as a gift, this iron would be very mean-spirited.

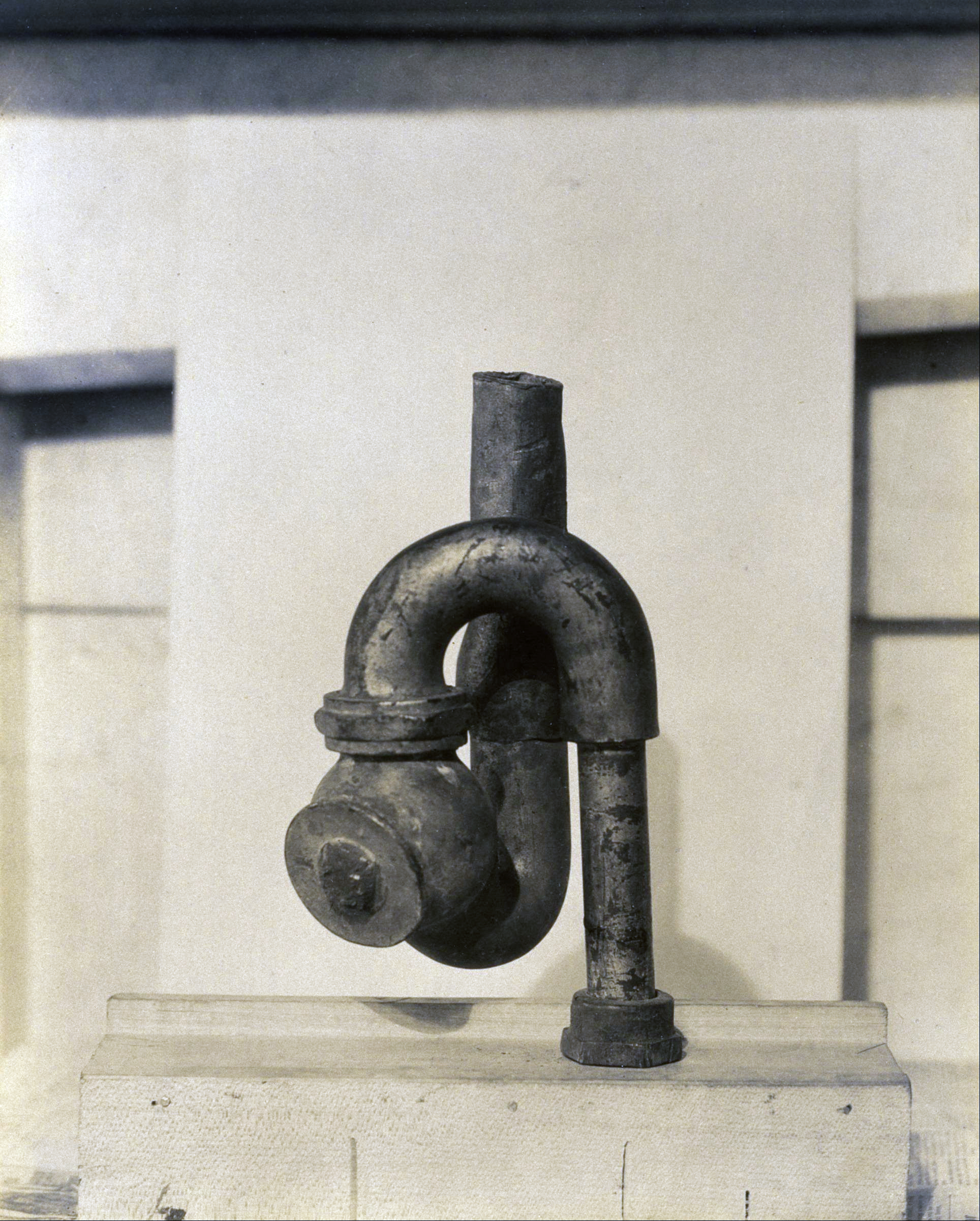

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and Morton Schamberg’s assisted readymade God was made by fitting a plumbing trap to a miter box. Separately, each object had a useful function. The water in the U-bend of a plumbing trap prevents sewer gas from seeping into the house, and a miter box helps guide a carpenter’s saw to make perfect right-angle or 45-degree cuts. Putting them together makes both dysfunctional, and the title God adds a note of sacrilege to further shock the middle-class public that might encounter the object in an art gallery.

Anti-art art

For a Dadaist, the fact that such found objects violate expectations for what art “should” be is part of their program of undermining social conventions. Indeed, the revered status of art and related concepts such as “creativity” and “originality” makes them an obvious target for a movement devoted to iconoclasm. In some cases the assault on art itself was direct.

The first “pure” readymade — unmodified and not combined with another object — was a bottle rack that was so obviously inartistic it was discarded by Duchamp’s family after the artist left France at the beginning of World War I. An unknown inscription on the original work may have helped guide interpretations, but Duchamp himself could not remember it in later years.

The underlying idea may have been a pun based on the French name of the object, égouttoir. The root word “goutte,” meaning drop (as in drop of water) suggests its function to drain the water out of bottles placed upside-down on its spikes. But Duchamp, who loved wordplay, may have also seen a pun on the word “goût” (taste), which in French as in English has aesthetic as well as culinary significance. Duchamp insisted that readymades be selected “based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste.”\(^{[3]}\) Indeed, the object is inartistic, anesthetic, tasteless — and placed in the center of an art gallery, the égouttoir could, by association, drain the taste from all the surrounding artworks.

Another example of Duchamp’s deliberately anti-art readymades is a postcard reproducing one of the world’s most famous and revered works of art, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, adorned with a mustache and goatee. Not only did Duchamp deface what is commonly regarded as a work of transcendent technical skill with a bit of crude graffiti, he violated gender norms as well by adding facial hair to a woman’s portrait. Beneath the image is more Duchampian wordplay: the initials L.H.O.O.Q., which read aloud in French sounds like “Elle a chaud au cul” — “she’s got a hot ass.”

From readymades to assemblages and conceptual art

Duchamp recognized that the power of readymades would diminish with proliferation, so he made only thirteen. The technique of creating art by carefully selecting and combining already-made objects has, however, proven enormously fruitful for other artists. Sculptures based on found objects have flourished since the “neo-Dada” assemblages of Robert Rauschenberg in the late 1950s. And although readymades remain controversial for many members of the general public, it is undoubtedly true that the contemporary art world now values artists’ concepts much more highly than their technical skills, just as Duchamp hoped.

Notes:

- Marcel Duchamp, interview with James Johnson Sweeney, The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, vol. XIII, no. 4-5 (1946), in Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, eds., The Writings of Marcel Duchamp (Oxford, 1973), p. 126.

- Duchamp, “Apropos of ‘Readymades’,” talk delivered in 1961 at the Museum of Modern Art, in The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, p. 141.

Additional resources:

Read more about Marcel Duchamp at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

MoMA curator Ann Temkin discusses readymade’s in MoMA’s collection

Dada Performance

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

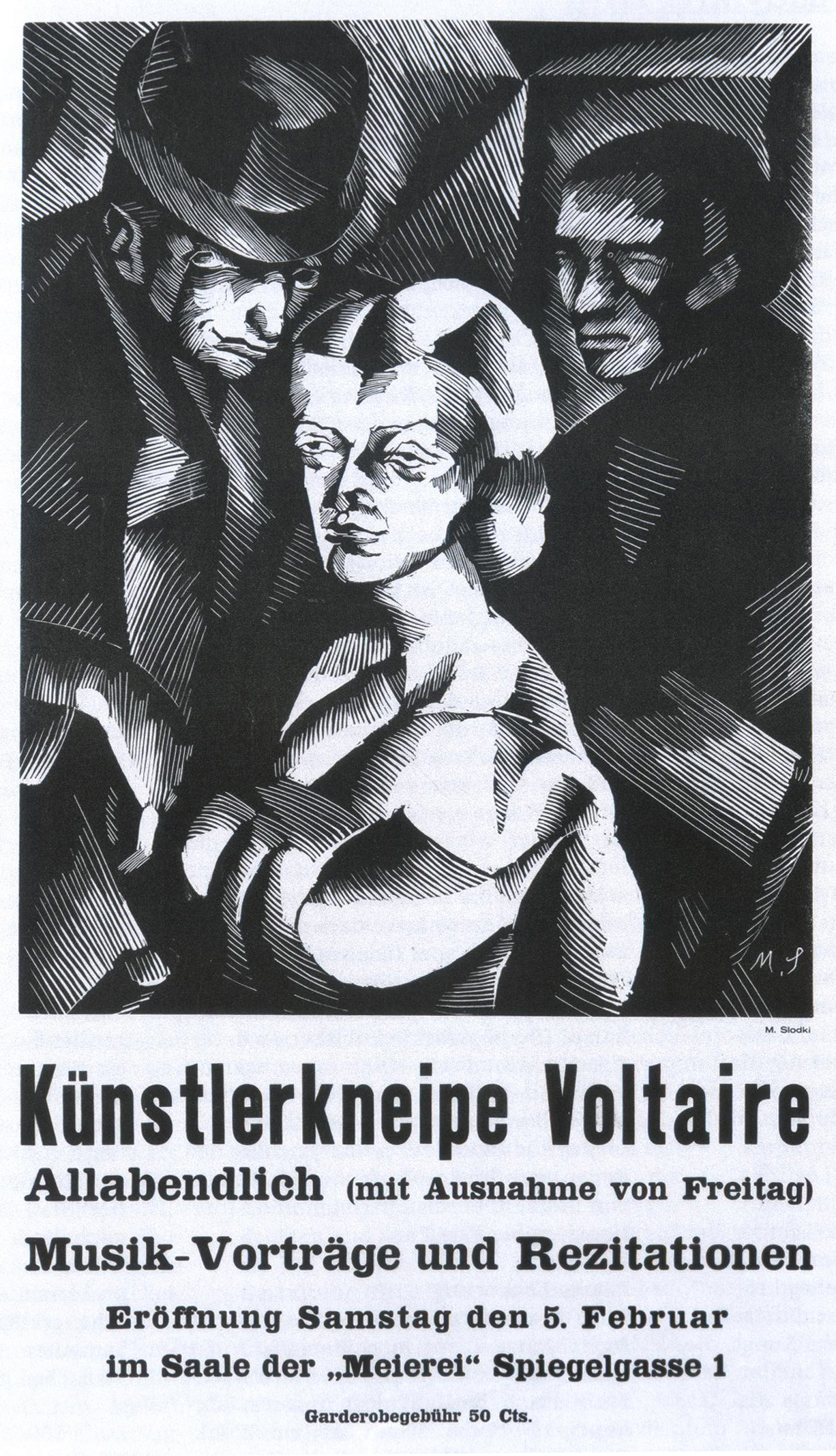

The Dadaists produced a bewildering variety of art, but the roots of Dada were in performance. The movement was founded in 1916 when German writer Hugo Ball and poet/performer Emmy Hennings received permission from the owner of the Meirei café in Zurich, Switzerland to use a small room as a venue for art performances. Ball recorded the opening of the Cabaret Voltaire in his diary on 2 February:

Under this name a group of young artists and writers has been formed whose aim is to create a center for artistic entertainment. The idea of the cabaret will be that guest artists will come and give musical performances and readings at the daily meetings. The young artists of Zurich, whatever their orientation, are invited to [make] suggestions and contributions of all kinds.

Translated in Leah Dickerman, ed., Dada (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2006), p. 22.

Artists and writers of many nationalities who had fled to neutral Switzerland to escape World War I responded to this invitation. In addition to Ball and Hennings, the core of the Zurich Dada group included the Romanians Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco (Iancu) and the Germans Hans Arp, Sophie Täuber, and Richard Huelsenbeck.

Ball and Hennings invited artists “whatever their orientation” and contributions “of all kinds,” setting the stage for a wildly diverse output that included Ball’s poetry, Hennings’ songs, Janco’s masks, Arp and Täuber’s abstract weavings and constructions, and Huelsenbeck’s chants. The disparate group was united by anti-war sentiment as well as general iconoclasm and irreverence, indicated by the name Voltaire, which referred to the 18th-century French satirist of religion and established authority.

A Dada soirée

Tristan Tzara documented the program of a Dada soirée held on 26 February 1916 in prose as breathlessly cascading and chaotic as the evening itself must have been:

DADA!! the latest thing!!! bourgeois syncope, BRUITIST [noise] music, the new rage, Tzara song dance protest — the bass drum — red light, policemen — songs cubist tableaux postcards Cabaret Voltaire song — simultaneous poem … two-step alcohol advertisement smoking toward the bells / we whisper: arrogance / Ms. Hennings’ silence, Janco declaration. transatlantic art = people rejoice star projected on Cubist dance in bells.

Tristan Tzara, “Chronique Zurichoise,” entry for 26 February 1916, in Richard Huelsenbeck, ed., Dada Almanach (Berlin, 1920), p. 11.

Despite its apparent randomness, this is a fairly straightforward listing of the kinds of performances the Dadaists favored, which, like a cabaret variety show, included dance, music, poetry recitations, costumed performances, and audience participation. However, most of these popular art forms were distorted beyond recognition.

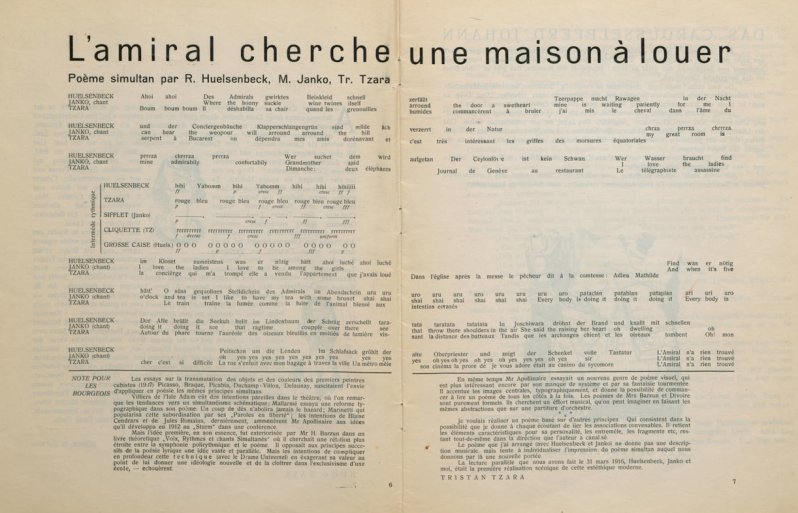

Dada poetry

For one type of recitation mentioned by Tzara, the “simultaneous poem,” different lines of text were read at the same time by different performers. In L’amiral cherche une maison à louer (The admiral is looking for a house to rent), three voices speak/sing the text simultaneously, Huelsenbeck in German, Janco in English, and Tzara in French, while playing a siren whistle, rattle, and bass drum. The performance provides a sensory and semantic cacophony that is only resolved in the final bleak line, when all three performers together recite in French, “The admiral found nothing.”

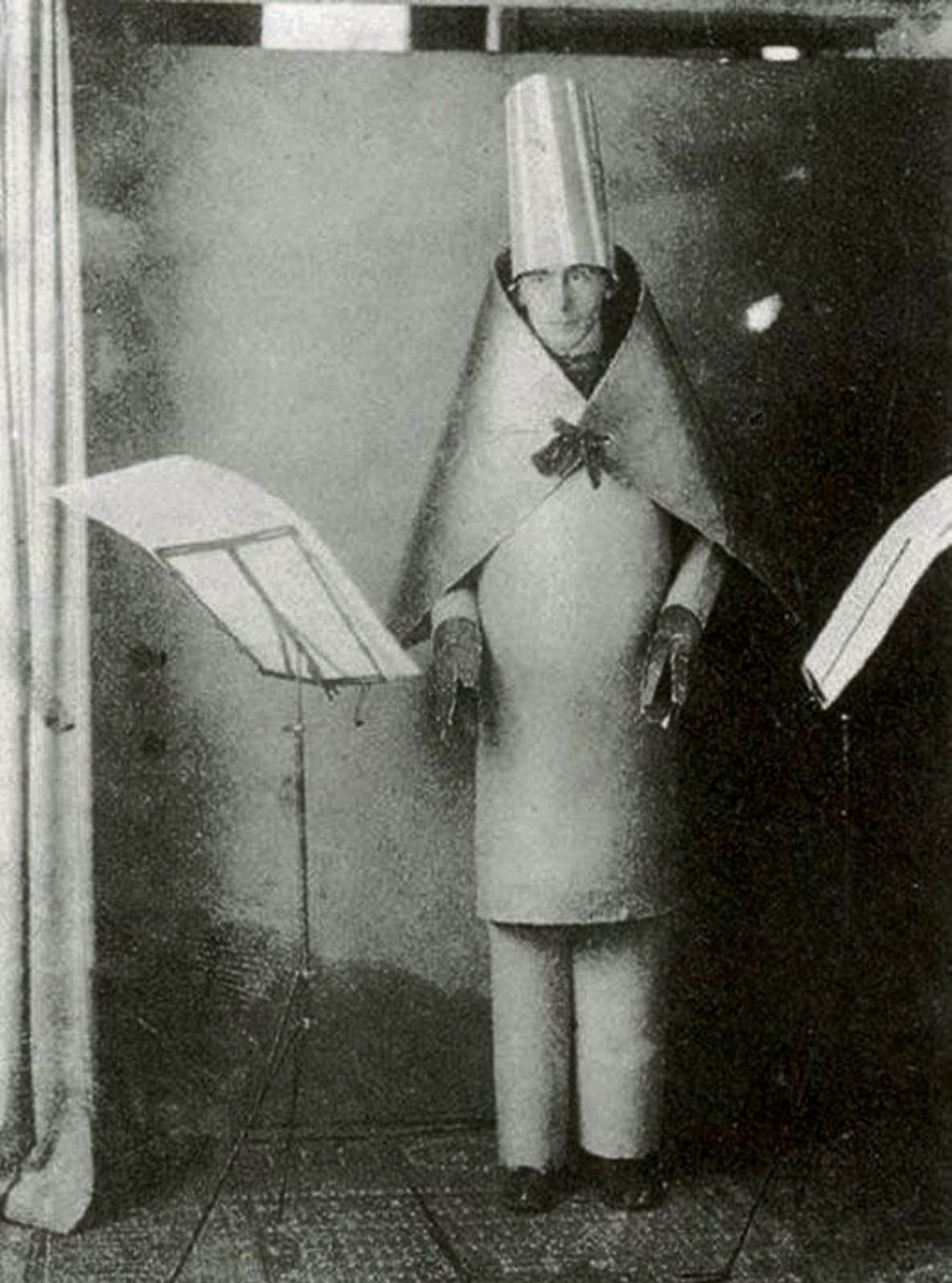

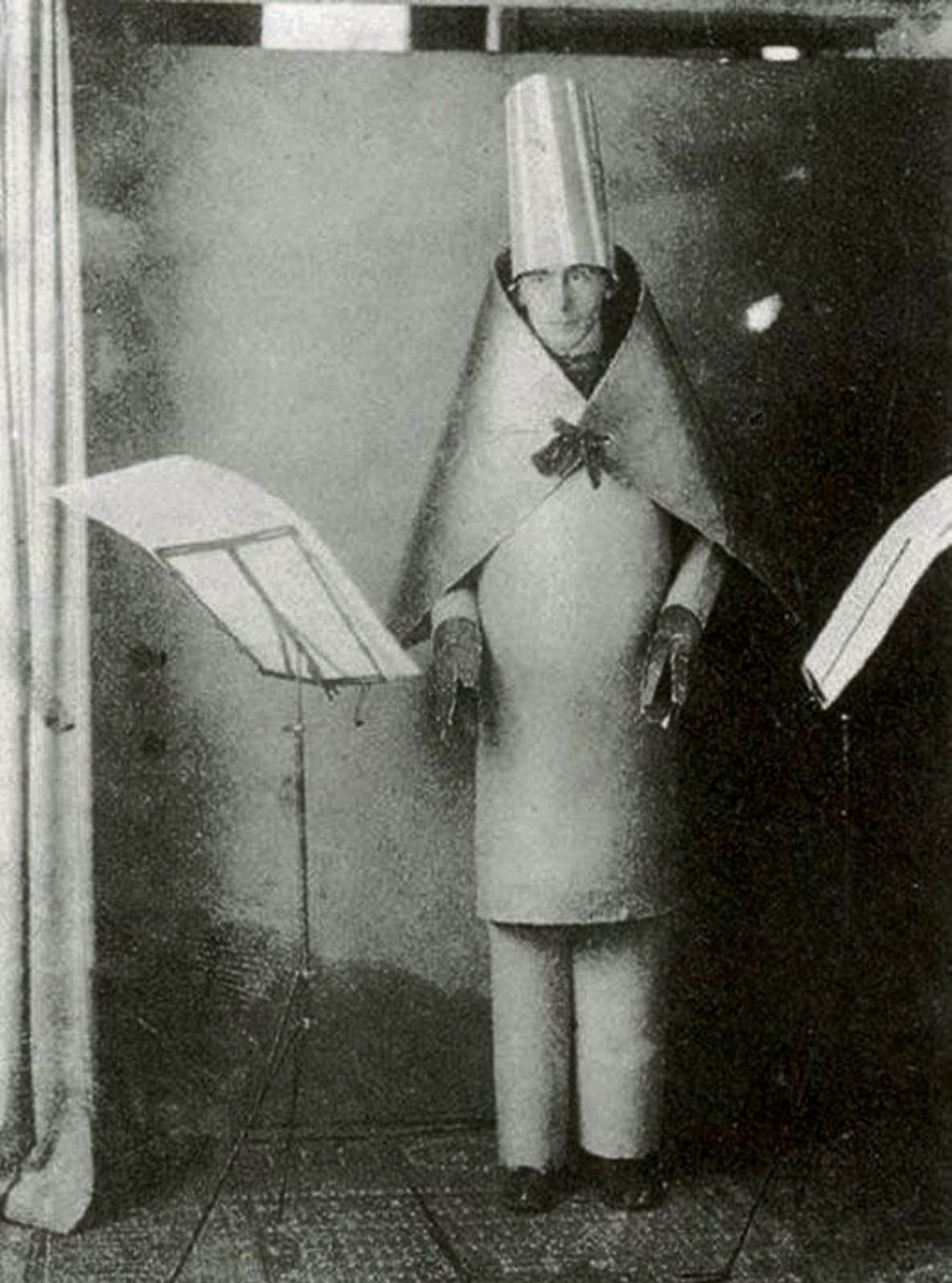

Another type of performance was the sound poem, which was made up of meaningless phonemes rather than words. For example, Ball’s poem Karawane begins, “jolifanto bambla o falli bambla / großiga m’pfa habla horem / egiga goramen / higo bloiko russula huju / hollaka hollala … .”

Ball recited this poem while wearing a cardboard costume vaguely resembling a bishop’s cape and miter that was so restricting he had to be carried on and off stage. The costume combined with the incomprehensible chant (Catholic masses were conducted in Latin at the time), created an obvious satire on religion.

Ball’s own description of this performance also suggests a sort of regression therapy in which he recollects seeing the liturgy as a child:

I do not know what gave me the idea of this music, but I began to chant my vowel sequences in a church style like a recitative … For a moment it seemed as if there were a pale, bewildered face in my Cubist mask, that half-frightened, half-curious face of a ten-year-old boy, trembling and hanging avidly on the priest’s words in the requiems and high masses in his home parish. Then the lights went out, as I had ordered, and bathed in sweat I was carried off the stage like a magical bishop.Translated in Dickerman, ed., Dada, p. 28.

Dada song and dance

More ordinary cabaret fare such as song-and-dance numbers were also distorted. With a gallows humor typical of those caught up in the horror of World War I, Emmy Hennings sang an altered version of a popular soldier’s marching song, ‘This is how we live [So leben wir],’ as “This is how we die, this is how we die, / We die every day, / Because they make it so comfortable to die.”

Dada soirées also included performers in Janco’s so-called African masks dancing and chanting Huelsenbeck’s African-sounding songs. The chants were at first entirely invented (with each verse ending in “umba, umba”), but later included some authentic African and Maori borrowings. Like Hugo Ball’s sound poems, such performances were intended as repudiations of Western rationalism and civilization, and possibly as invocations of healing primal states.

While the Dadaists’ intention was to valorize non-Western cultures, their “primitivist” performances are today considered problematic. Like many modern artists who embraced “primitivism” the Dadaists appropriated non-Western cultural artifacts without understanding or acknowledging their original values and purposes. They assumed African cultures and peoples were non-rational and tended to generalize all African and Oceanic cultures into a single homogeneous entity.

Among her many projects, Sophie Täuber participated in Dada performances as a dancer in a troupe choreographed by Rudolf Laban, who was known for rejecting classical movement in favor of more natural body language. A photograph of her in a pose at the opening of the Galerie Dada while wearing a mask by Janco shows another artistic convention broken by the Dadists. In a typical cabaret the attractive appearance (and implied sexual availability) of the female performers was taken for granted, but as Hans Richter noted in his memoir of Zurich Dada, the masks and costumes hid the “pretty faces” and “slender bodies” of the dancers[1].

Täuber also produced figurative sculpture, mostly reduced to basic geometric shapes either turned on a lathe or constructed out of found materials. The marionettes she produced for a 1918 staging of Carlo Gozzi’s König Hirsch (King Stag), for example, are made of thread spools and other wood scraps jointed with eye hooks. Although not produced in the context of Dada, these marionettes evoke many of the same themes, including the playful use of found materials and the uncomfortable transformation of organic, apparently free human beings into rigidly mechanized automatons.

‘Our cabaret is a gesture’

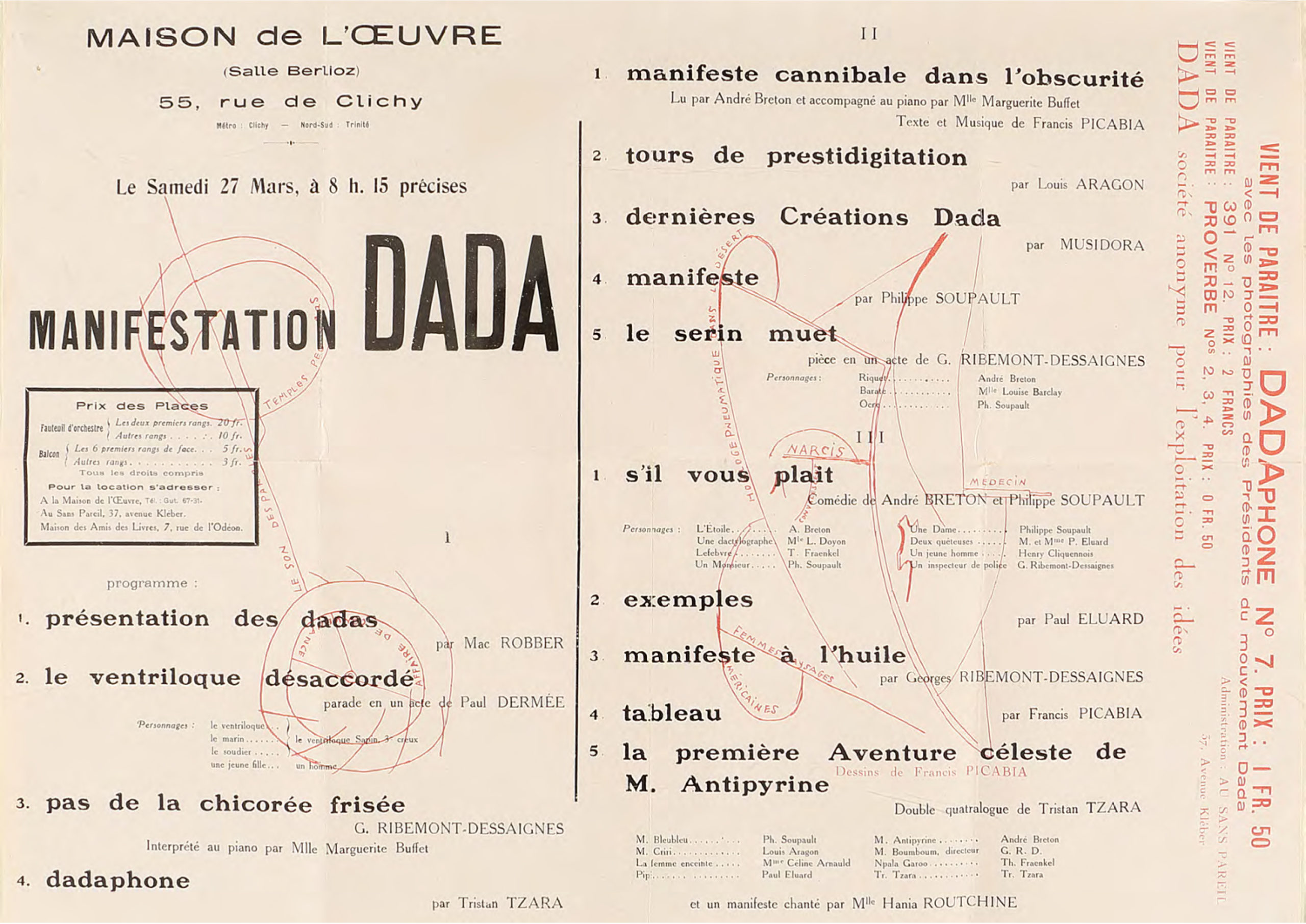

Dada was a cosmopolitan movement at a time of rising nationalism, and it quickly became a global phenomenon, spreading from Zurich and New York to Paris, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, and other locales. The program for a 1920 Paris Dada soirée included a reading of Francis Picabia’s Cannibal Manifesto, which insulted the audience, and a piano piece by Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes titled “March of the Curly Endive,” which was written by chance using a pocket roulette wheel.

What are such performances about? It would violate the absurdist creed of Dada to attempt to submit them to reason and order. Perhaps Hugo Ball put it best when he said, “Our cabaret is a gesture. Every word that is spoken and sung here says at least one thing: that this humiliating age has not succeeded in winning our respect.”[2]

Dada was anti-war, anti-authority, anti-nationalist, anti-convention, anti-reason, anti-bourgeois, anti-capitalist, and anti-art. Performance was of particular value to the Dadaists because its combination of media expanded the potential for multi-sensory and poly-semantic assault; and also because its direct interaction with the public gave it a greater potential to agitate and to shock.

Notes:

- Hans Richter, Dada Art and Anti-Art (London, 1997), pp. 79-80.

- Translated in Dickerman, ed., Dada, p. 25.

Additional resources:

Leah Dickerman, ed., Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris (National Gallery of Art, 2005)

Audio performance of a version of L’amiral cherche une maison a louer

Jody Blake, “Ragging the War: Dada,” in Le Tumulte Noir: Modernist Art and Popular Entertainment in Jazz-Age Paris, 1900-1930 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), pp. 59-82.

Read more about “primitivism” in modern art

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2

by DR. TOM FOLLAND

When the French artist Marcel Duchamp arrived by ship to New York in 1915, his reputation, as the saying goes, preceded him. Two years earlier, in 1913, after an inauspicious debut in France, Duchamp sent his painting Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) to America. His now famous depiction of a body in motion walking down a narrow stairway quickly drew outrage from a public unfamiliar with current trends in European art, and became a succès de scandale (success from scandal) that launched Duchamp into the American spotlight. But why was the painting so shocking?

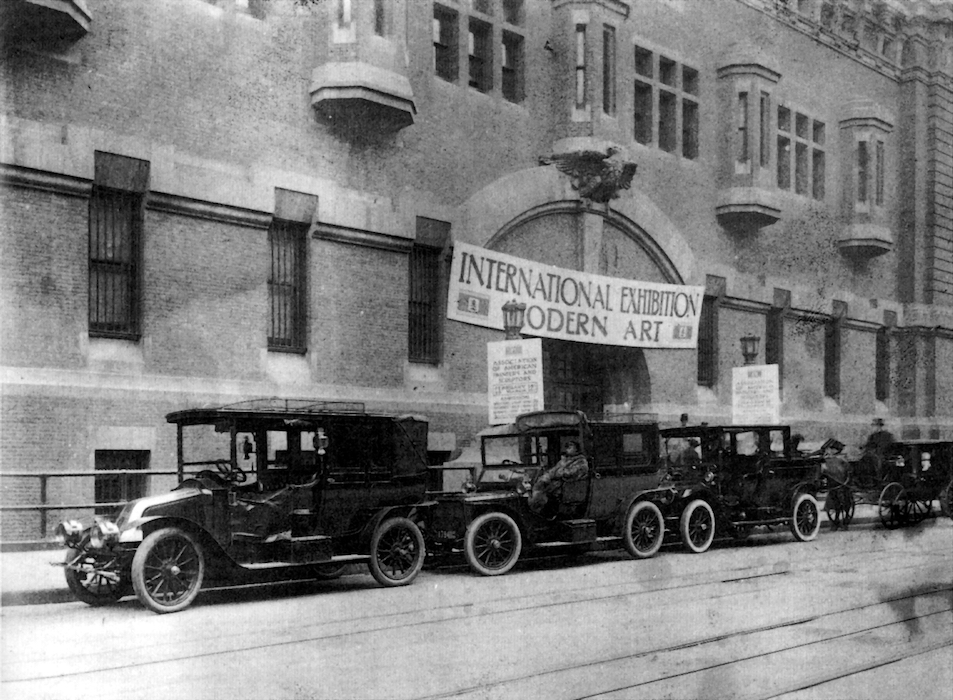

The 1913 exhibition, dubbed “The Armory Show” for its installation in New York City’s 69th Regiment Armory, proposed to survey modern art from Romanticism of the early nineteenth-century to Cubism of the present.

The group that organized the 1913 exhibition called themselves the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. The sprawling exhibition also included American art and no doubt the organizers hoped that they might promote the work of an American vanguard in the company of illustrious European modernists. All that was quickly forgotten however, as it was Duchamp’s painting that captured attention as the exhibition toured the country. The Armory Show also had the unfortunate effect of showcasing the provincialism of American artists who seemed to paint as if nothing had changed since the Realist and Impressionist movements of the nineteenth-century. In the face of this realization, the American artist William Glackens, one of the exhibition’s organizers wryly lamented, “we have not yet arrived at a National Art."\(^{1}\)

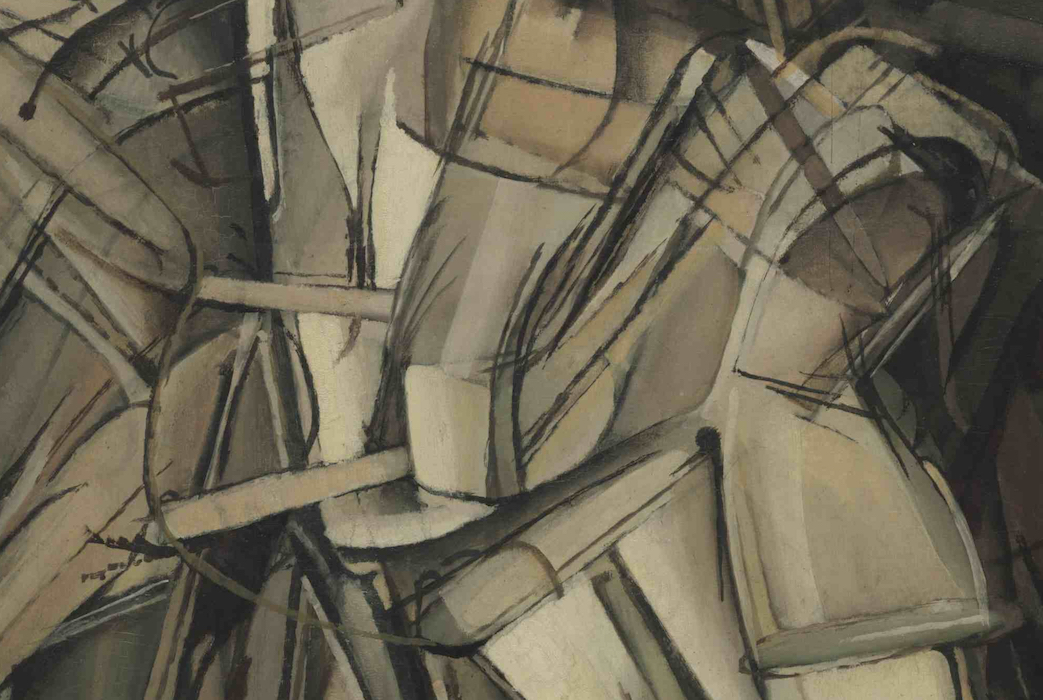

As the exhibition toured the country, Duchamp’s painting captured widespread attention for its unconventional rendition of the nude. He positioned the figure—its upright stance reiterated by the vertical orientation of the canvas—in a descending diagonal from upper left to lower right. A tangle of shattered geometric shapes suggest the stairs in the lower left corner of the composition while rows of receding stairs at the upper left and right frame the strangely multiplying female form as she descends. But what a descent! The figure recalls the whirling of a robot promenading down a set of stairs as if in some sort of futurist movie, or perhaps a magic lantern show—a popular form of image projection in the years before the development of cinema.

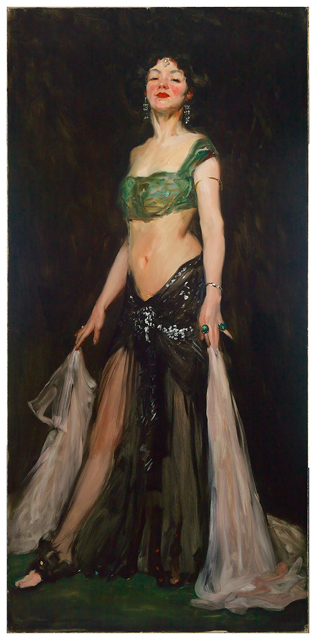

Duchamp’s painting was certainly a far cry from what passed as modern painting in the United States at that time. One of the most progressive movements was the Ashcan School, whose members used gritty palettes in expressive renderings of city street scenes, immigrant subjects, and other urban themes that seemed shockingly modern. Robert Henri’s Salome (left) for example, shows an actress striding across a narrow stage in a rather brazen manner. Her head tilts back as she gazes at the viewer and her hands sweep aside the folds of her skirt to reveal her legs. In contrast to Henri, Duchamp’s subject matter is nearly indecipherable. His figure registers as female because of the convention, at least in recent years, that expects most nudes in art to be women. Moreover, the style was an extreme distortion of even the most contemporary kind of realism at the time. It was, perhaps, for these reasons that the painting challenged audiences, such as the uncomprehending critic who described Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) as “the explosion of a shingle factory.”\(^{2}\)

Like much European modernism (think Cubism, Futurism or Orp

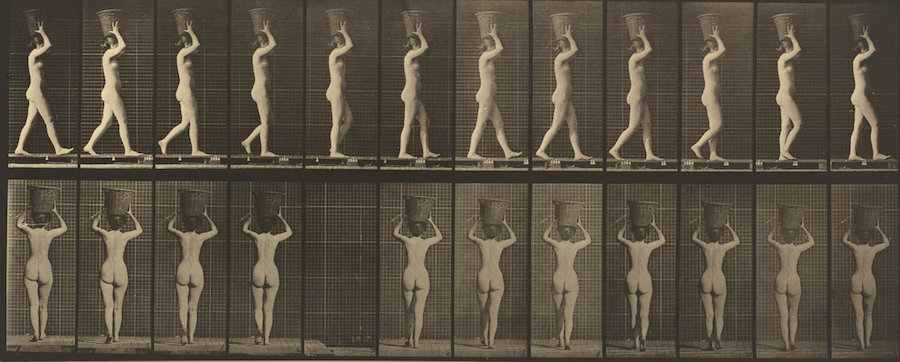

Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) did not waiver from its origins in Cubism. But, the unusual sense of motion conveyed in the painting may reflect an additional influence in the photography of Eadweard Muybridge (below) or Étienne-Jules Marey, who had invented a camera shutter in 1882 that allowed for an early version of time-lapse photography. Notice how the figure approximates the blur one might see with time-lapse imagery. Even painters of the Puteaux group, whom Duchamp had known in France, disapproved (they were interested in furthering the original Cubist investigations into pictorial space and perception of Picasso and Braque). In Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), Duchamp had welded a cubist style of shattered picture planes to the kind of painting being done by the Italian avant-garde movement Futurism, typified by Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. The painting, as a result, is sometimes referred to as a Cubo-futurist work.

However unresponsive the reception for Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) was in France, it became a charged symbol of the modern in America. The female form had, of course, suffered avant-garde assault for some time in Europe reaching as far back as Manet’s Olympia (1863), which showed a nude female reclining across a flatly painted interior. Matisse and his followers had even further abstracted the figure in their fauvist paintings. But in America, the lingering traces of the classical style with its idealizing forms still prevailed even among more contemporary painters. Duchamp turned a venerable subject—the female nude, and all it embodied about western culture and traditions of beauty—into something monstrous and worse, something machine-like. As in his later readymades—which turned ordinary commercial objects into works of art—Duchamp embraced the very thing art was supposed to reject: the cold logic of industrial production.

Notes

\(^{1}\)“The American Section The National Art, An Interview with The Chairman of the Domestic Committee, W.M.J. Glackens,” Arts And Decoration, vol. 2 (March 1913), p. 159.

\(^{2}\)Julian Street, “Why I became a Cubist,” Everybody’s Magazine 28, June, 1913.

Additional resources:

This work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Marcel Duchamp on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Dada and the Readymade from the National Gallery of Art

Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt and Company), 1996.

Art as concept: Marcel Duchamp, In Advance of the Broken Arm

by SAL KHAN and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Marcel Duchamp, In Advance of the Broken Arm, 1964 (fourth version, after lost original of November 1915) (MoMA)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917/1964, porcelain urinal, paint (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

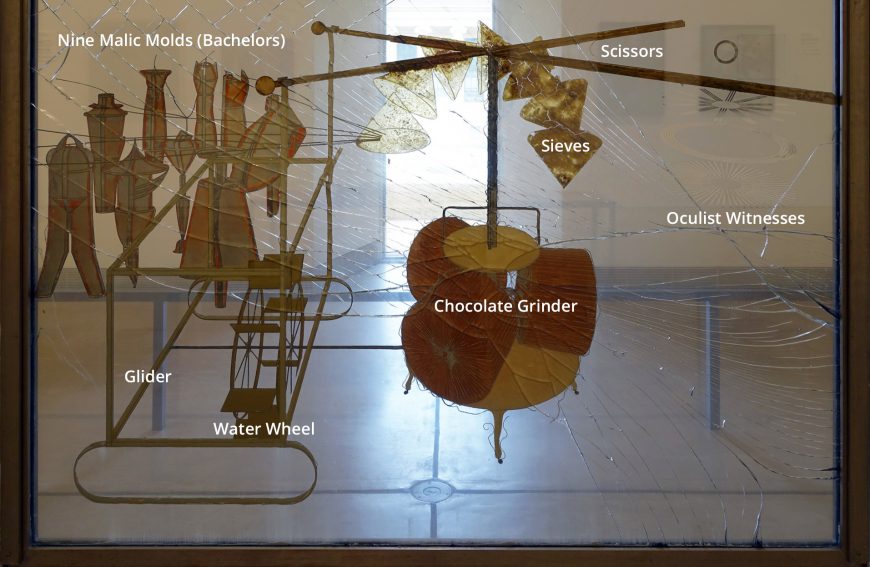

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)

by DR. LARA KUYKENDALL

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Estate of Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

You might know Marcel Duchamp because of his Fountain—the urinal that he signed (as R. Mutt) and submitted to the Society of Independent Artists art show in 1917. This “readymade” was a whimsical and iconoclastic gesture—in keeping with the spirit of the New York Dada circle. Like his Dada compatriots, including Francis Picabia and Man Ray, Duchamp reveled in humor, wordplay, and the radical redefinition of art during and just after World War I.

Art driven by ideas

Even before Fountain, Duchamp had made a big splash at New York’s 1913 Armory Show with his controversial cubo-futurist painting Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912).But Duchamp said he wanted to get away from painting as a strategy for art-making. This was partly a reaction against the popular French saying, “bête comme un peintre,” which means “stupid as a painter” (a phrase used to describe someone foolish—much like the English “dumb as a box of rocks”). To say someone is “stupid as a painter” is to say that painters only translate what they see and that painting is not an intellectual activity. Duchamp disagreed, and strove to make works, like Fountain, that were driven by intellect (what would come to be known as “conceptual art”) and defied standards of beauty and artistic technique. Duchamp called The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even his “hilarious picture” and it, too, engages wit, absurdity, non-traditional materials, and conceptualism to push the boundaries of what was acceptable and possible in the art world of his generation.

Dust, wire, glue and varnish

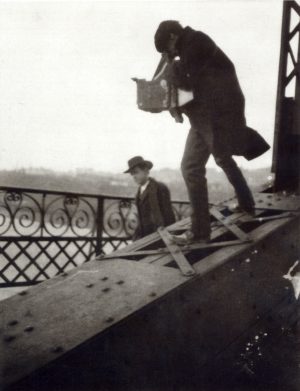

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even is often called the Large Glass because that is precisely what it is: two pieces of glass, which are stacked vertically and framed like a double-hung window to reach over nine feet tall. Though the Large Glass is essentially a flat, two-dimensional object, it is emphatically not a painting, as it is mostly transparent—you can walk around it and view it from both sides—and Duchamp avoided using traditional materials like canvas and oil paint. Instead, he concocted the imagery on the glass surface out of wire, foil, glue, and varnish. He also allowed dust to collect on the glass as it laid flat in his studio, which he affixed with adhesive. Man Ray’s photograph, Dust Breeding (1920), shows just how dirty the glass got.

Duchamp stopped working on the Large Glass in 1923, after eight years, not because it was complete, but because he decided it should remain “definitively unfinished.” Later, in 1927, when the glass was en route to collector Katherine Dreier’s house from an exhibition in Brooklyn, he was thrilled to discover it had been damaged, saying the accidental cracking finished the work in a way that he never could have.

The Large Glass is a curious contraption; it looks a bit like a mechanical diagram and was designed it to function like an allegorical machine. He made preliminary paintings and drawings for components of the Large Glass including Chocolate Grinder (No. 2) (1914). He also amassed an impressive collection of cryptic notes that he brought together in The Green Box (1934), which scholars have used to interpret the work’s many different meanings—from the frustrations of love and sex, to the physics of electromagnetism and the fourth dimension. To understand how the Large Glass works like a machine we must imagine its components in motion.

The bride and the bachelors

The action begins in the upper left corner with the “Bride,” the element that resembles a bug or a tree. She flirts by stripping for the “Bachelors” in the lower register. The Bachelors are the nine vaguely anthropomorphic cylinders in the lower left section of the glass, and they think the Bride is very attractive. Each Bachelor is trying to win her affection, but they exist in a completely different zone, and are having a hard time communicating with her.

As the Bachelors become excited their forms fill up with what Duchamp called an “illuminating gas” (invisible). This gas causes an “imaginary waterfall” to turn the water wheel (mill) beneath them. That action makes the rectangular glider slide back and forth, which moves the scissors above, which makes the chocolate grinder churn. All of that motion builds up, as the gas from the Bachelors flows into the cone-shaped sieves. The gas that represents the Bachelors’ desire for the Bride transforms into liquid and flows into the lower right corner. Next, the liquid is propelled through the three circular elements, and through a magnifying glass (Oculist Witnesses), and shoots into the Bride’s realm above. The goal for each Bachelor is to land his shot within one of the three square windows inside of the cloud that hovers at the top of the glass (Draft Piston or Nets). If he can do that, he will win the Bride and they will be able to consummate their love physically. If you look closely, you can see nine small holes on the right side of the Bride’s register, which Duchamp marked by firing matches with paint on the tips through a toy cannon. Unfortunately, only one of those shots even came close to its target. Thus, the Bachelors cannot reach the Bride and their love for her remains unfulfilled.

Duchamp loved science. To create the Large Glass, he experimented not only with new media but also with recent scientific theories as if he were in a laboratory. On top of the tale of amorous attraction and frustration, Duchamp layered ideas about such scientific phenomena as electromagnetism and telegraphy. The way the Bride communicates her erotic feelings from her pane of glass to the Bachelors’ realm below relates to the power of electricity and the vibratory waves in the electromagnetic field mobilized in wireless telegraphy. The Bride’s form actually resembles the telegraphic antenna on the top of the Eiffel Tower that was the source of much popular interest in Duchamp’s day. As an antenna, she can send and receive unseen messages through space, but the Bachelors are not so advanced. They are able to receive her communications, but their only response comes in the form of those failed shots from the toy canon, which are at best a rudimentary and rather pathetic means of winning her love.

Duchamp’s writings reveal that he imagined the Bride’s realm as the mysterious fourth dimension of space, a higher plane from the Bachelors who live in our common three-dimensional world. This accounts for their miscommunications and failed attempts at finding love. In the Large Glass, Duchamp brought art, science, sex, and love together in an absurdly humorous way. Watching machines try to fall in love; imagining the bug-tree-antenna Bride strip for Bachelors who cannot reach her; understanding that the object was made with dust, shattered glass, and marks made randomly by a toy cannon; and tying that drama to the complicated workings and invisible forces of science is surprising, playful, and oddly hilarious.

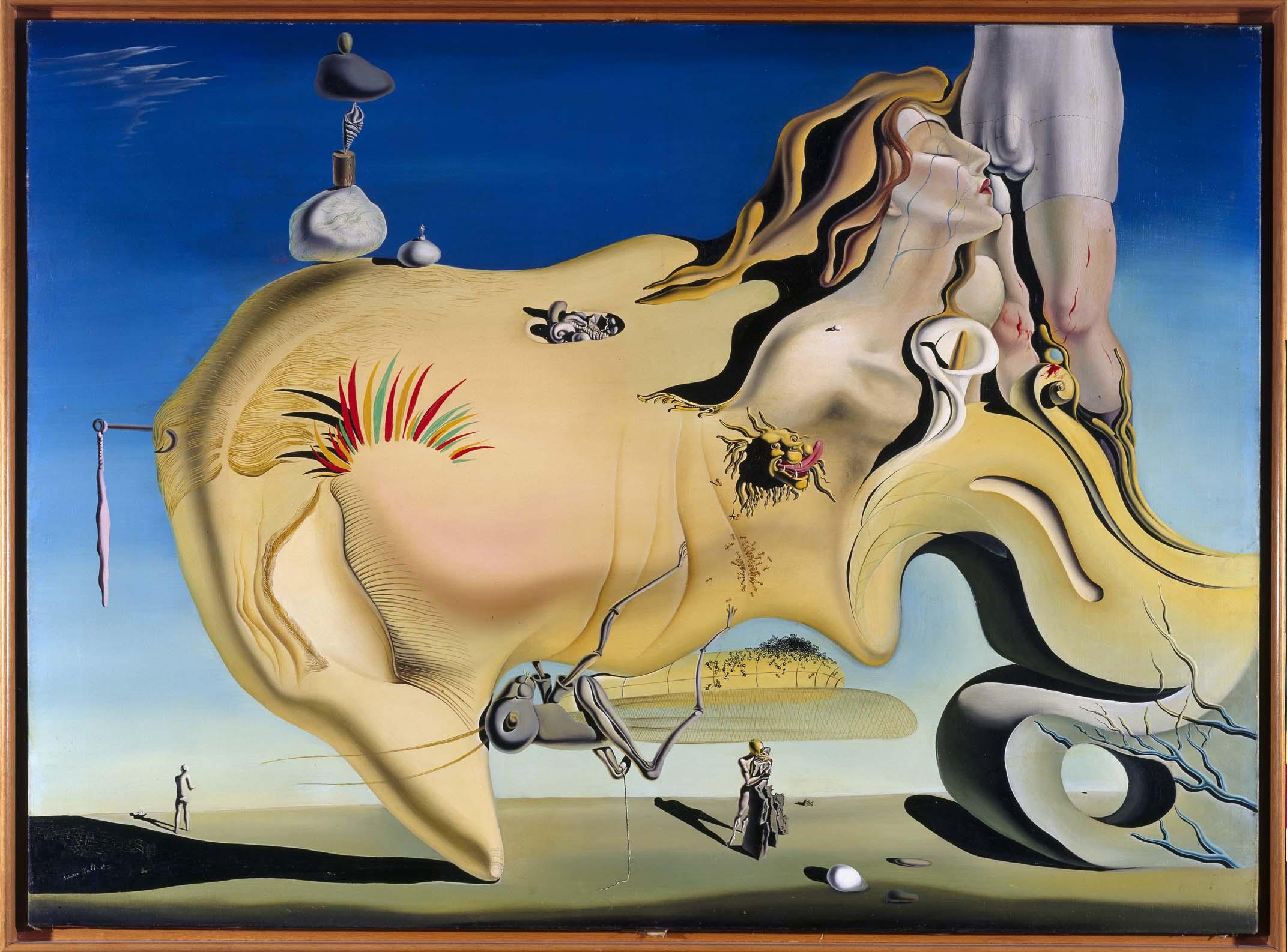

From art to chess