10.1: A beginner's guide

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147827

An Introduction to Photography in the Early 20th Century

Photography undergoes extraordinary changes in the early part of the twentieth century. This can be said of every other type of visual representation, however, but unique to photography is the transformed perception of the medium. In order to understand this change in perception and use—why photography appealed to artists by the early 1900s, and how it was incorporated into artistic practices by the 1920s—we need to start by looking back.

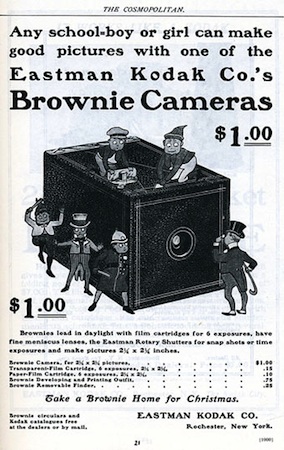

In the later nineteenth century, photography spread in its popularity, and inventions like the Kodak #1 camera (1888) made it accessible to the upper-middle class consumer; the Kodak Brownie camera, which cost far less, reached the middle class by 1900.

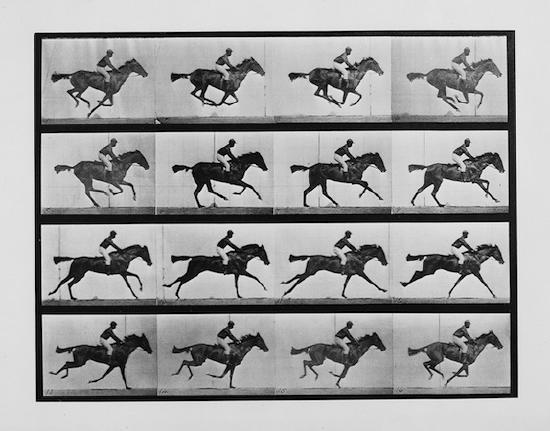

In the sciences (and pseudo-sciences), photographs gained credibility as objective evidence because they could document people, places, and events. Photographers like Eadweard Muybridge created portfolios of photographs to measure human and animal locomotion. His celebrated images recorded incremental stages of movement too rapid for the human eye to observe, and his work fulfilled the camera’s promise to enhance, or even create new forms of scientific study.

In the arts, the medium was valued for its replication of exact details, and for its reproduction of artworks for publication. But photographers struggled for artistic recognition throughout the century. It was not until in Paris’s Universal Exposition of 1859, twenty years after the invention of the medium, that photography and “art” (painting, engraving, and sculpture) were displayed next to one another for the first time; separate entrances to each exhibition space, however, preserved a physical and symbolic distinction between the two groups. After all, photographs are mechanically reproduced images: Kodak’s marketing strategy (“You press the button, we do the rest,”) points directly to the “effortlessness” of the medium.

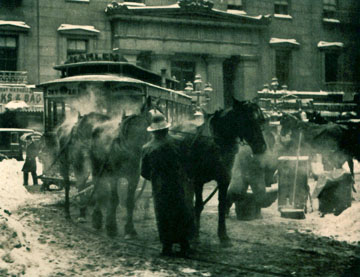

Since art was deemed the product of imagination, skill, and craft, how could a photograph (made with an instrument and light-sensitive chemicals instead of brush and paint) ever be considered its equivalent? And if its purpose was to reproduce details precisely, and from nature, how could photographs be acceptable if negatives were “manipulated,” or if photographs were retouched? Because of these questions, amateur photographers formed casual groups and official societies to challenge such conceptions of the medium. They—along with elite art world figures like Alfred Stieglitz—promoted the late nineteenth-century style of “art photography,” and produced low-contrast, warm-toned images like The Terminal that highlighted the medium’s potential for originality.

So what transforms the perception of photography in the early twentieth century? Social and cultural change—on a massive, unprecedented scale.Like everyone else, artists were radically affected by industrialization, political revolution, trench warfare, airplanes, talking motion pictures, radios, automobiles, and much more—and they wanted to create art that was as radical and “new” as modern life itself.

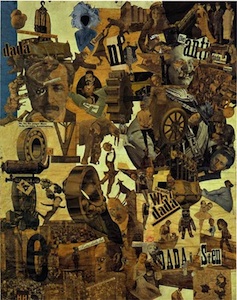

If we consider the work of the Cubists and Futurists, we often think of their works in terms of simultaneity and speed, destruction and reconstruction. Dadaists, too, challenged the boundaries of traditional art with performances, poetry, installations, and photomontage that use the materials of everyday culture instead of paint, ink, canvas, or bronze.

By the early 1920s, technology becomes a vehicle of progress and change, and instills hope in many after the devastations of World War I. For avant-garde (“ahead of the crowd”) artists, photography becomes incredibly appealing for its associations with technology, the everyday, and science—precisely the reasons it was denigrated a half-century earlier. The camera’s technology of mechanical reproduction made it the fastest, most modern, and arguably, the most relevant form of visual representation in the post-WWI era. Photography, then, seemed to offer more than a new method of image-making—it offered the chance to change paradigms of vision and representation.

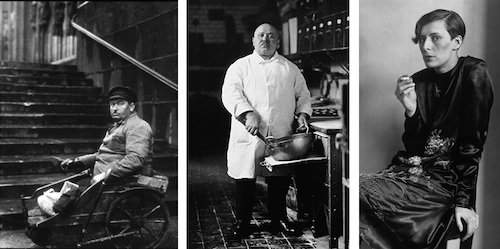

With August Sander’s portraits such as Disabled Man, Pastry Chef, or Secretary at a Radio Station, Cologne, we see an artist attempting to document—systematically—modern types of people, as a means to understand changing notions of class, race, profession, ethnicity, and other constructs of identity. Sander transforms the practice of portraiture with these sensational, arresting images. These figures reveal as much about the German professions as they do about self-image.

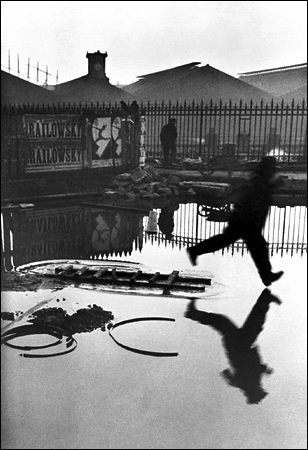

Cartier-Bresson’s leaping figure in Behind the Gare St. Lazare reflects the potential for photography to capture individual moments in time—to freeze them, hold them, and recreate them. Because of his approach, Cartier-Bresson is often considered a pioneer of photojournalism. This sense of spontaneity, of accuracy, and of the ephemeral corresponded to the racing tempo of modern culture (think of factories, cars, trains, and the rapid pace of people in growing urban centers).

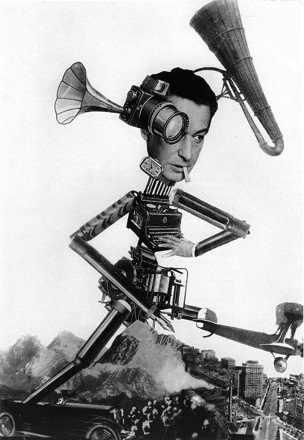

Umbo’s photomontage The Roving Reporter shows how modern technologies transform our perception of the world—and our ability to communicate within it. His camera-eyed, colossal observer (a real-life journalist named Egon Erwin Kisch) demonstrates photography’s ability to alter and enhance the senses. In the early twentieth-century, this medium offered a potentially transformative vision for artists, who sought new ways to see, represent, and understand the rapidly changing world around them.

Contemporary Art, an introduction

“Getting” Contemporary Art

It’s ironic that many people say they don’t “get” contemporary art because, unlike Egyptian tomb painting or Greek sculpture, art made since 1960 reflects our own recent past. It speaks to the dramatic social, political and technological changes of the last 50 years, and it questions many of society’s values and assumptions—a tendency of postmodernism, a concept sometimes used to describe contemporary art. What makes today’s art especially challenging is that, like the world around us, it has become more diverse and cannot be easily defined through a list of visual characteristics, artistic themes or cultural concerns.

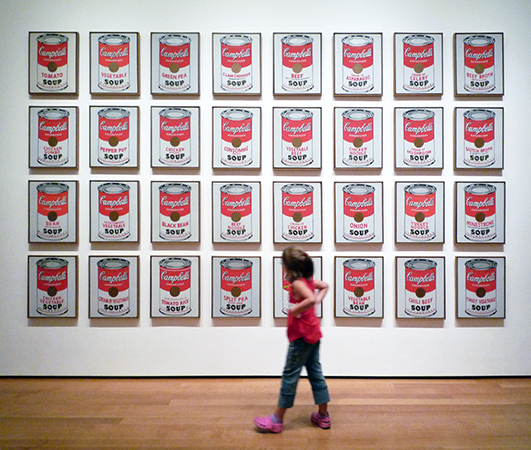

Minimalism and Pop Art, two major art movements of the early 1960s, offer clues to the different directions of art in the late 20th and 21st century. Both rejected established expectations about art’s aesthetic qualities and need for originality. Minimalist objects are spare geometric forms, often made from industrial processes and materials, which lack surface details, expressive markings, and any discernible meaning. Pop Art took its subject matter from low-brow sources like comic books and advertising. Like Minimalism, its use of commercial techniques eliminated emotional content implied by the artist’s individual approach, something that had been important to the previous generation of modern painters. The result was that both movements effectively blurred the line distinguishing fine art from more ordinary aspects of life, and forced us to reconsider art’s place and purpose in the world.

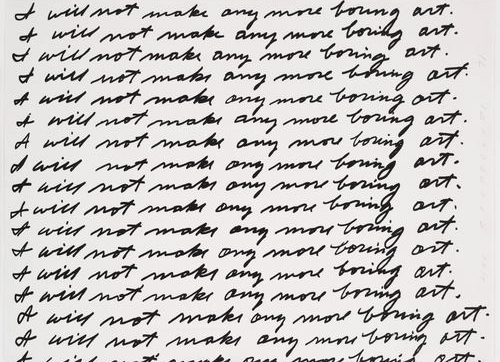

Shifting Strategies

Minimalism and Pop Art paved the way for later artists to explore questions about the conceptual nature of art, its form, its production, and its ability to communicate in different ways. In the late 1960s and 1970s, these ideas led to a “dematerialization of art,” when artists turned away from painting and sculpture to experiment with new formats including photography, film and video, performance art, large-scale installations and earth works. Although some critics of the time foretold “the death of painting,” art today encompasses a broad range of traditional and experimental media, including works that rely on Internet technology and other scientific innovations.

Contemporary artists continue to use a varied vocabulary of abstract and representational forms to convey their ideas. It is important to remember that the art of our time did not develop in a vacuum; rather, it reflects the social and political concerns of its cultural context. For example, artists like Judy Chicago, who were inspired by the feminist movement of the early 1970s, embraced imagery and art forms that had historical connections to women.

In the 1980s, artists appropriated the style and methods of mass media advertising to investigate issues of cultural authority and identity politics. More recently, artists like Maya Lin, who designed the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial Wall in Washington D.C., and Richard Serra, who was loosely associated with Minimalism in the 1960s, have adapted characteristics of Minimalist art to create new abstract sculptures that encourage more personal interaction and emotional response among viewers.

These shifting strategies to engage the viewer show how contemporary art’s significance exists beyond the object itself. Its meaning develops from cultural discourse, interpretation and a range of individual understandings, in addition to the formal and conceptual problems that first motivated the artist. In this way, the art of our times may serve as a catalyst for an on-going process of open discussion and intellectual inquiry about the world today.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Representation and abstraction: looking at Millais and Newman

by SAL KHAN, DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Vir Heroicus Sublimus, 1950-51 (MoMA)

What’s “heroic” about a painting that looks like a craft project on HGTV? This comparison suggests an answer.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Art and context: Monet’s Cliff Walk at Pourville and Malevich’s White on White

by SAL KHAN, DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

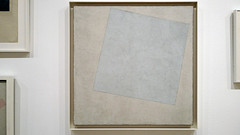

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Claude Monet, Cliff Walk at Pourville, 1882, oil on canvas, 26-1/8 x 32-7/16 inches (66.5 x 82.3 cm) (Art Institute of Chicago), and Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918, oil on canvas, 31 1/4 x 31 1/4″ (79.4 x 79.4 cm) (MoMA)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: