7.14: c. 1700 - 1775- Rococo

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147804

Rococo

A style favored by the aristocracy — particularly in France.

c. 1700 - 1775

A beginner’s guide to Rococo art

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

The beginnings of Rococo

In the early years of the 1700s, at the end of the reign of Louis XIV (who dies in 1715), there was a shift away from the classicism and “Grand Manner” (based on the art of Poussin) that had governed the art of the preceding 50 years in France, toward a new style that we call Rococo. The Palace of Versailles (a royal chateau that was the center of political power) was abandoned by the aristocracy, who once again took up residence in Paris. A shift away from the monarchy, toward the aristocracy characterizes the art of this period.

What kind of lifestyle did the aristocracy lead? Remember that the aristocracy had enormous political power as well as enormous wealth. Many chose leisure as a pursuit and became involved themselves in romantic intrigues. Indeed, they created a culture of luxury and excess that formed a stark contrast to the lives of most people in France. The aristocracy—only a small percentage of the population of France—owned over 90% of its wealth. A small, but growing middle class will not sit still with this for long (remember the French Revolution of 1789).

Fragonard’s The Swing

As with most Rococo paintings, the subject of Fragonard’s The Swing is not very complicated. Two lovers have conspired to get an older fellow to push the young lady in the swing while her lover hides in the bushes. Their idea is that—as she goes up in the swing, she can part her legs, and her lover can get a tantalizing view up her skirt.

The figures are surrounded by a lush, overgrown garden. A sculptured figure to the left puts his fingers to his mouth, as though saying “hush,” while another sculpture in the background shows two cupid figures cuddled together. The colors are pastel pale pinks and greens, and although we have a sense of movement and a prominent diagonal line—the painting lacks the seriousness of a baroque painting.

If you look closely you can see the loose brushstrokes in the pink silk dress—and as she opens her legs, we get a glimpse of her stockings and garter belt. It was precisely this kind of painting that the philosophers of the Enlightenment were soon to condemn. They demanded a new style of art, one that showed an example of moral behavior, of human beings at their most noble.

Additional resources:

The Swing at the Wallace Collection

Fragonard on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

18th century European dress on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

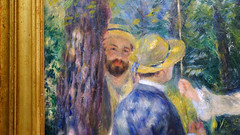

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Formation of a French School: the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture

by DANIELLA BERMAN

In a room filled to the brim with painting and sculpture, well-dressed men in powdered wigs assemble around a desk while stragglers chat with their neighbors. Jean-Baptiste Martin’s small painting depicts a meeting of the distinguished French art academy without an artist’s tool in sight—only the ornate room situates the scene in the Louvre palace. The choice to not show the artists at work, but rather as fashionable gentlemen engaged in sociable intellectual exchange speaks directly to the early history of the French Royal Academy.

The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) was established in 1648. It oversaw—and held a monopoly over—the arts in France until 1793. The institution provided indispensable training for artists through both hands-on instruction and lectures, access to prestigious commissions, and the opportunity to exhibit their work. Significantly, it also controlled the arts by privileging certain subjects and by establishing a hierarchy among its members. This hierarchical structure ultimately led to the Académie’s dissolution during the French Revolution. However, the Académie in Paris became the model for many art academies across Europe and in the colonial Americas.

Foundation

This preeminent training organization for painters and sculptors was founded in response to two related concerns: a nationalistic desire to establish a decidedly French artistic tradition, and the need for a large number of well-trained artists to fulfill important commissions for the royal circle. Previous monarchs had imported artists (primarily from Flanders and Italy), to execute major projects. In contrast, King Louis XIV sought to cultivate and support French artists as part of his grander project of self-fashioning, with art playing a vital role in the construction of the royal image.

The Académie quickly rose to prominence, in conjunction with the Ministry of Arts (responsible for construction, decoration, and upkeep of the king’s buildings) and the First Painter to the King—the most prestigious title an artist could achieve. Two men were integral to the institution’s early history: Jean-Baptiste Colbert, an increasingly influential statesman who acted as the institution’s protector, and the artist Charles Le Brun, who would go on to be both First Painter and the Académie’s Director. Both men sought to elevate the status of artists by emphasizing their intellectual and creative capacities, and both sought to differentiate members of the Académie—academicians— from guild members (guilds were a medieval system that strictly regulated artisans). The Académie, whose members were financially supported by the King, moved into its permanent location at the Louvre Palace in 1692, further reinforcing the institution’s status. Given such institutional preoccupations, Martin’s decision to show artists as gentlemen socializing rather than as artisans laboring takes on new significance.

Hierarchies

From its inception, the Académie was structured around hierarchy. There were distinct levels of membership that an artist could advance through over time. In art, too, there was a hierarchy: painting was prioritized over sculpture, and certain subjects were considered more noble than others. To become a member, artists submitted work for evaluation by academicians, who accepted them at a certain level, based on the kind of subjects they aspired to paint. If they passed this first phase, applicants would execute a “reception piece” depicting a subject chosen by the academicians.

The Académie divided paintings into five categories, or genres, ranked in terms of difficulty and prestige:

- History Painting—encompassing highbrow subjects taken from the classical tradition, the bible, or allegories, this type of painting was considered the highest genre because it required proficiency in depicting the human body, as well as imagination and intellect to depict what could not be seen. These were often large-scale multi-figure paintings.

- Portraiture—focusing on capturing likeness, this genre was prestigious, and certainly lucrative, but less so than history painting. Portraitists were derided for “merely” copying nature rather than inventing (an oversimplification as few portraits were executed entirely from life).

- Genre Painting—depicting scenes of everyday life, this genre included the human figure but ostensibly did not represent grand ideas, although many genre paintings had moralizing undertones. Genre paintings were smaller in size than history paintings, further detracting from their prestige.

- Landscapes—consisting of all representations of rural or urban topography, real or imagined, this genre became especially popular during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

- Still Life Painting—often indulging in the juxtaposition of colors and textures, these paintings represented inanimate (often luxury) objects and drew heavily on the seventeenth-century Dutch tradition of such subjects. While at times other moralizing symbols such as memento mori (reminders of human mortality) were included, these were not an intrinsic part of the genre, which was considered to require no invention on the part of the artist (since, they were painting what they could see).

Training

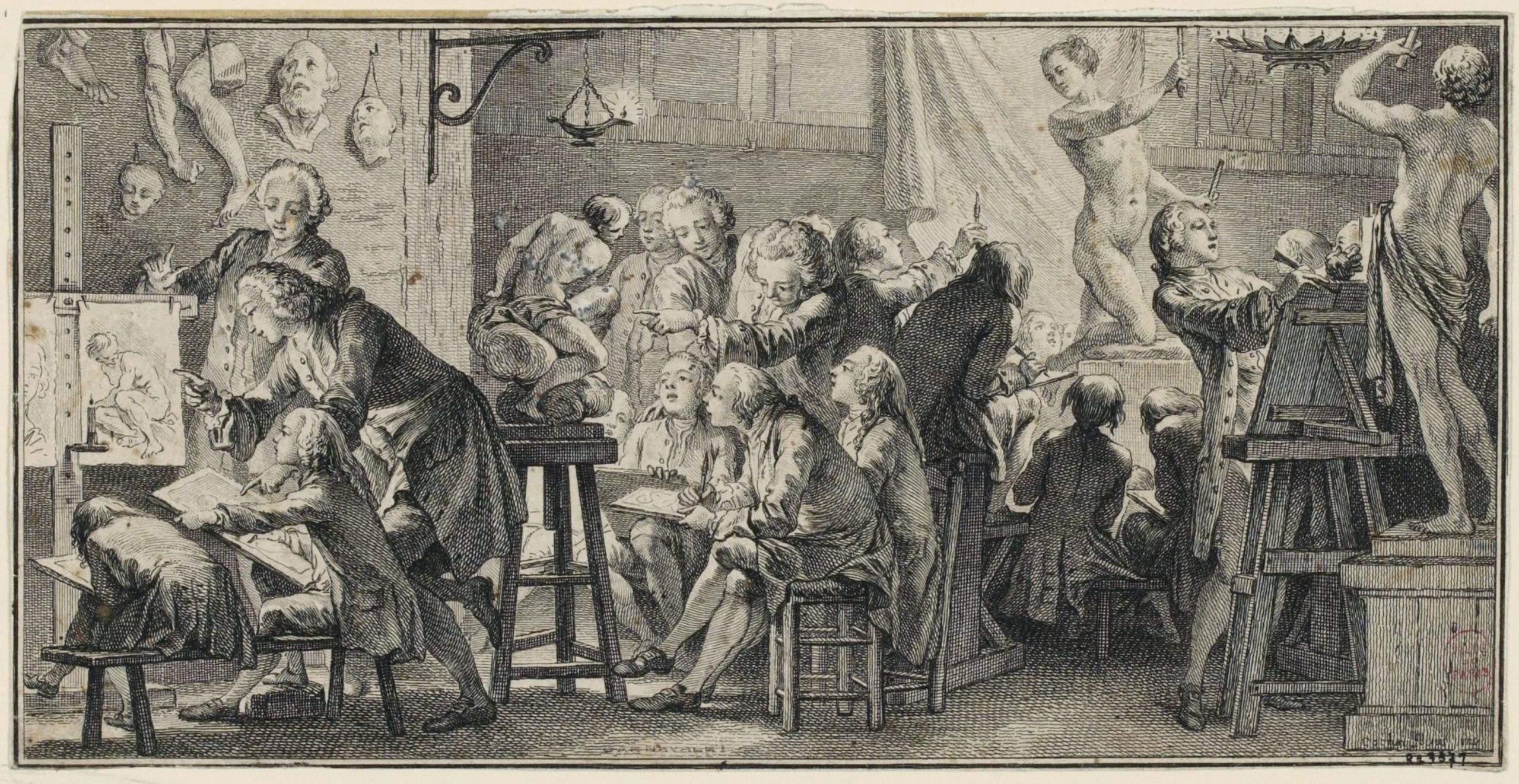

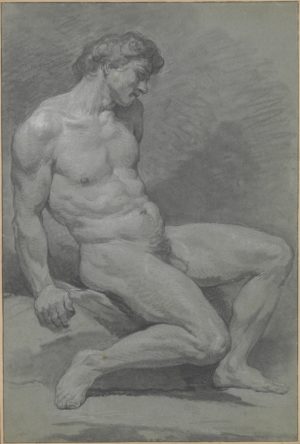

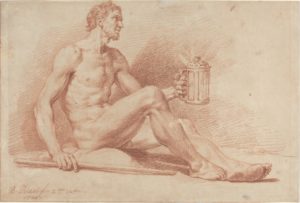

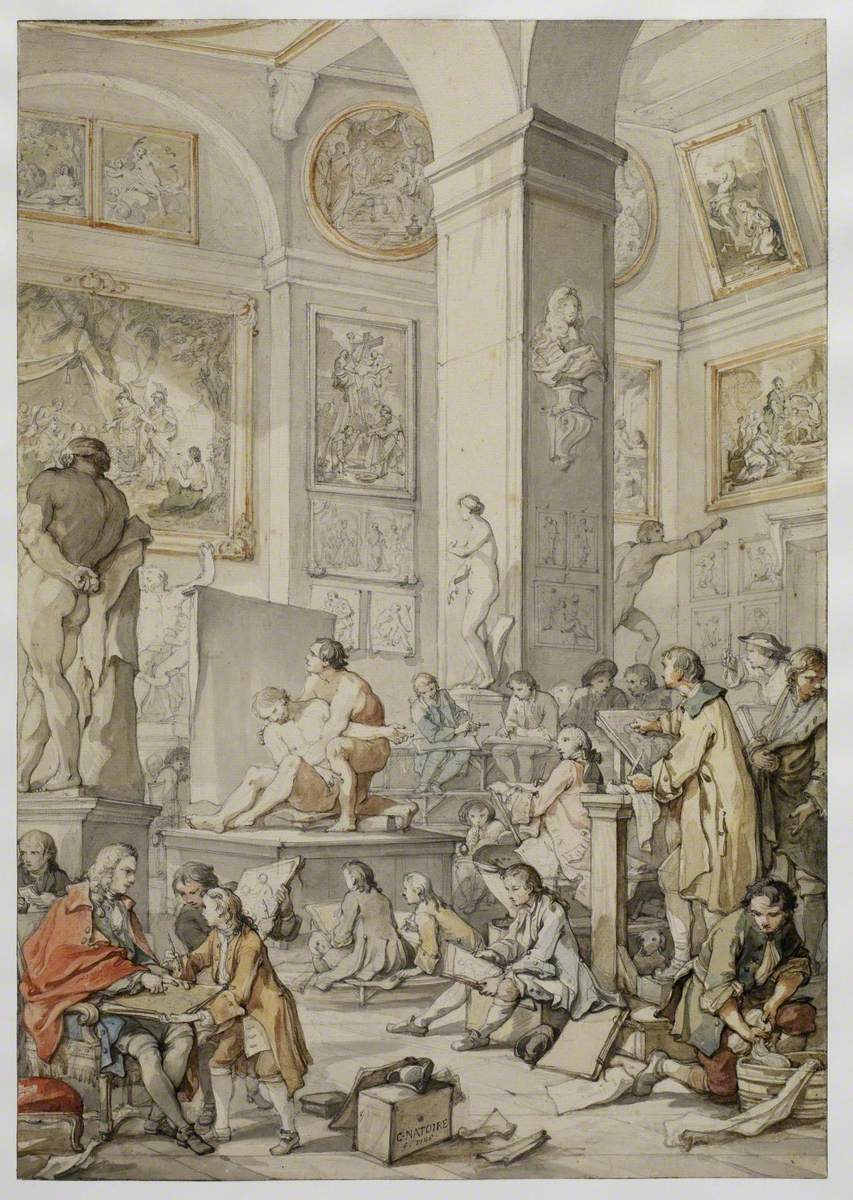

Academic instruction was centered on drawing (following the precedent of Italian drawing schools established in the sixteenth century). The Académie maintained a rigid curriculum to instruct artists, as recorded in contemporary accounts and depictions. An etching illustrating a 1763 description of the “school of art” shows how students first learned to draw by copying drawings and engravings (seen on the left) before moving on to drawing plaster casts to learn how to translate the three-dimensional form into two dimensions (seen at center). Students would then copy large-scale sculpture (as seen at the right-most edge) before being allowed to draw the live nude model (as seen in the middle-right portion, slightly set back from the foreground). Drawing the male nude form was the bedrock of the Académie’s curriculum, an essential building block for painters, particularly those destined to produce history paintings. Students produced many single-figure nude studies, known as académies, such as this example from Nicolas Bernard Lépicié. Props could be added subsequently to transform the posed bodies into identifiable figures, as Bernard Picart has done with the drawing Male Nude with a Lamp, where the figure, with the addition of a lamp, becomes the philosopher Diogenes.

In a lively drawing, Charles Natoire depicts himself in a red cape in the left foreground, providing feedback on students’ drawings. The majority of students work independently, focused on the two nude models in an intertwined pose selected by the supervising professor. The opportunity to study two interacting male bodies was a rarer and more challenging exercise.

Outside of the Académie’s official spaces, academicians would provide advanced students opportunities to draw nude female models. In addition to supervising drawing education, each professor selected students to be part of his studio. This is where artists actually learned to paint or sculpt by emulating their teacher, often contributing to his large-scale commissions. Studio practices varied, and not all studio members were necessarily enrolled Académie students.

Both academicians and students attended lectures addressing theoretical and practical aspects of artistic practice, such as the importance of expressions or how to apply paint to ensure longevity. These were offered by professors and so-called amateurs. These honorary Académie members were not professional artists but art lovers and “friends of artists”—often from the nobility—who advised artists on questions of composition, aesthetics, and iconography and often championed certain artists, sometimes as patrons or collectors.

The draw of Rome

The classical tradition was central to the Académie’s curriculum. In 1666, the Académie opened a satellite in Rome to facilitate students’ study of antiquity. In 1674, the Académie established the Prix de Rome (Rome Prize), a prestigious award that allowed its most promising artists to study in Rome for three to five years. While the focus of the French Academy in Rome was facilitating the study of classical antiquity, students also drew after important Renaissance and Baroque artworks, as seen in Hubert Robert’s red chalk drawing depicting an artist copying Domenichino’s fresco in a Roman church.

While in Rome, these Académie students—called pensionnaires—studied canonical artworks and regularly sent their drawings and copies after important works back to Paris to demonstrate their progress. Although not part of the formal curriculum, most artists explored the Roman environs, taking inspiration from the rich landscape, diverse topography, and colorful scenes of peasant life. Important connections were forged in Rome with other artists, patrons, and supporters.

Salons and the rise of public opinion

Beginning in 1667, the Académie established exhibitions to provide members with the crucial opportunity to display their work to a wider audience, thereby cultivating potential patrons and critical attention. Held annually and, later, biannually, these exhibitions came to be known as Salons, after the Louvre’s salon carré where they took place after 1725. The Salon became a significant space of artistic exchange and an important opportunity to view art prior to the formation of the public art museum.

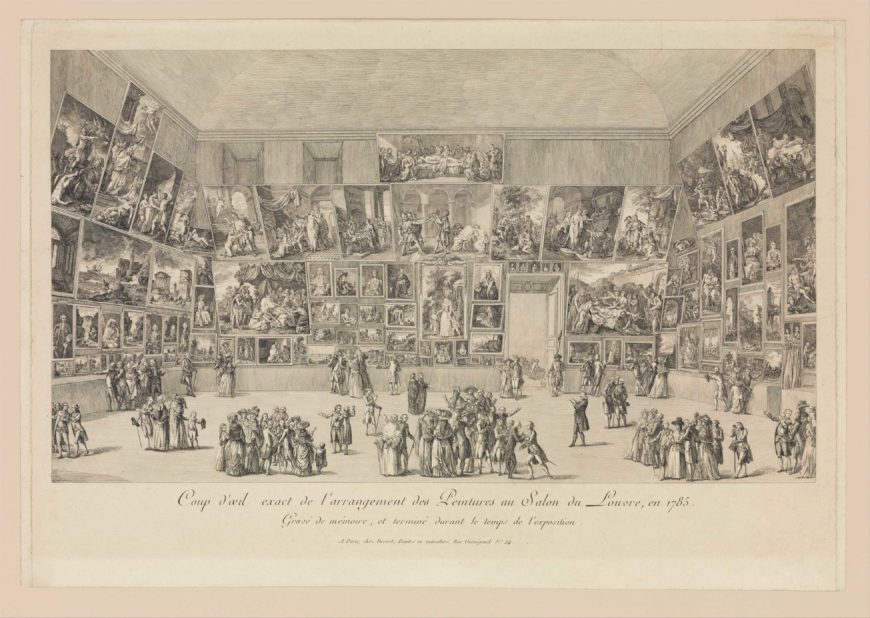

Artworks in the Salon were selected by a jury of academicians. Paintings were displayed according to size and genre, with larger works (history painting and portraiture) occupying the more prestigious higher levels, as can be seen in an engraving of the Salon of 1785 where Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii features prominently in the center. With the 1737 introduction of a broader public to the Salon came the advent of public opinion and the emergence of art criticism. The Académie published a booklet that listed the displayed works, organized by the artist’s rank, called the livret. Art collectors and learned Salon-goers penned opinions analyzing the artistic and intellectual merit of the exhibited artworks; some of these, like those written by philosopher Denis Diderot, were meant for a small community of like-minded individuals both in France and beyond, but increasingly art criticism was printed in newspapers for access by a broader public.

Genders and genres

The Académie was a male space, for the most part; some painters accepted female students in their studios, particularly in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Women artists were barred by propriety from studying the male nude figure, a core aspect of Academic training. This rendered them unable to become officially recognized history painters, and they were therefore restricted to genres considered to be less intellectually rigorous. During its 150-year long history, the Académie only welcomed four women as full members: Marie-Thérèse Reboul was admitted in 1757; Anne Vallayer-Coster was admitted in 1770; Adélaïde Labille-Guiard and Elisabeth Vigée-LeBrun were both admitted in 1783.

Despite their acceptance to the Académie, these women had limited options. Painting primarily still-lifes (like Reboul), Vallayer-Coster elevated that genre with large-scale ornate compositions. Labille-Guiard led a large studio of female students and was well-known as a prominent portraitist. So too did Vigée-LeBrun, who pushed the boundaries of genre and her gender by occasionally painting allegories, including her reception piece for the Académie. Familial connections (in the case of Reboul, Labille-Guiard, and Vigée-LeBrun) or royal protectors (in the case of Vallayer-Coster, Labille-Guiard, and Vigée-LeBrun) played vital roles in their success. Without such champions, female artists were unable to penetrate the patriarchal institution of the Académie. Still, their work and personal lives were subjected to undue public scrutiny and their achievements were often maligned.

Abolition and afterlives

In the 1780s, the Académie came under attack by members and outsiders for politicizing the distribution of prizes and honors. Its rigid hierarchies, inequitable structures, and rampant nepotism were incompatible with the Revolution’s core values of Liberty and Equality. Major artists who had benefited from the institution lobbied for its dissolution. With the overthrow of the monarchy and Louis XVI’s execution, institutions with indelible royal connections were scrutinized and deemed irrelevant. The Académie was abolished on August 8, 1793 by order of the National Convention.

After several years of hardship for artists brought about by the erosion of royal, noble, and ecclesiastical patronage during the Revolution, the Directory government revived many of the structures of the Académie in establishing a National Institute of Sciences and Arts (Institut nationale des sciences et des arts, subsequently Institut de France) in 1795. The new organization’s membership included many former academicians, who reinstated certain aspects of the now-defunct Académie, such as the Rome Prize in 1797. The hierarchy of genres, inculcated in the Académie’s members and audiences, remained central to understanding the arts throughout the nineteenth century.

Additional resources

Denis Diderot, Salons (tome I – III), Paris: J.L.J Briere Libraire, 1821

The Salon and the Royal Academy in the Nineteenth Century

Laura Auricchio, Melissa Lee Hyde, Mary Sheriff, and Jordana Pomeroy, Royalists to Romantics: Women Artists from the Louvre, Versailles, and Other French National Collections (Scala Arts Publishers, Inc., 2012).

Colin B Bailey, “‘Artists Drawing Everywhere’: The Rococo and Enlightenment in France,” in Jennifer Tonkovich et al., Drawn to Greatness: Master Drawings from the Thaw Collection (New York: Morgan Library & Museum, 2017).

Albert Boime, “Cultural Politics of the Art Academy,” The Eighteenth Century vol. 35, no 3 (1994), pp. 203–22.

Thomas E. Crow, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth Century Paris (Yale University Press, 1985).

Christian Michel, The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture: The Birth of the French School, 1648–1793, translation by Chris Miller (The Getty Research Institute, 2018).

Richard Wrigley, The Origins of French Art Criticism: from the Ancien Régime to the Restoration (Oxford University Press, 1993).

Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to Cythera

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to Cythera, 1717, oil on canvas, 4′ 3″ x 6′ 4 1/2″ (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

François Boucher, Madame de Pompadour

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): François Boucher, Madame de Pompadour, oil on canvas, 1750 (extension of canvas and additional painting likely added by Boucher later) (Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Tiepolo Family

by JEREMY MILLER

Eighteenth-century Venice was dominated by the Tiepolo family of artists. Venice had lost influence as an artistic center since the sixteenth-century, the era of Titian and Veronese. Exciting new artists such as Caravaggio and the Carracci brothers were working primarily in central Italy, Rome in particular. By adopting the tradition of grand, allegorical ceiling painting for the aristocratic elite, the father-son team of Giambattista and Domenico Tiepolo brought Venice once again into the center of artistic life. The Tiepolo family also helped define many of the qualities we think of as Rococo.

What most people notice first about Tiepolo paintings are the colors. Pastels in complimentary schemes lend a soft, often romantic quality to otherwise active scenes. The use of dramatic poses and simultaneous narrative are reinforced by the tension inherent in the color schemes, keeping the pictures lively and engaging. This combination of precision, apparent ease, and liveliness was referred to as sprezzatura, and the Tiepolo family came to define it as an artistic trait.

The Residenz

Between 1750 and 1753 Domenico and his father lived and worked in Würzburg, Germany. Giambattista Tiepolo had been commissioned to decorate certain areas of the Residenz, or royal residence, and he brought Domenico along to assist him with this work. The frescoes they produced are generally considered to be the greatest masterpieces of the Tiepolo family workshop. The two artists worked so well together that it is in fact impossible to differentiate exactly which passages were painted by which artist.

The ceiling above the grand staircase of the Residenz contains an allegorical depiction of Apollo presiding over the planets and continents. At each edge of the curved ceiling, just above each wall, are symbolic representations of Europe, Asia, Africa and America. Giambattista and Domenico designed each section to be viewed from specific “stopping points” specified by the patron. Here visitors climbing the staircase could pause to admire the work, and appreciate how the perspective of the fresco seemed to adjust to their position in the room. This imaginative use of perspective helps the allegorical image come alive for viewers, but can make this three-dimensional painting look awkward in two-dimensional photographs.

Etchings

The Tiepolo family also explored new media and artistic subjects, particularly Domenico. In 1753 he published a series of twenty-four etchings titled Picturesque Ideas on the Flight into Egypt which were executed during the breaks in activity at the Residenz. These sheets were produced in a cinematic way, much like modern storyboards. The story unfolds page by page, and the viewer is brought into the scenes through the way the images are composed. In the fourth image, we see the backs of the onlookers at the right side of the composition as the holy family departs on their journey. The architectural framing of the image encourages the viewer to imagine being one of the citizens of Jerusalem, witnessing the departure of Mary, Joseph, and their newly born son. The strong diagonals that make up most of the image enhance the sense of movement, and help to place the viewer in relation to the image’s protagonists.

Despite Domenico’s attempts to bring his family’s artistic practice into the age of Enlightenment, the Tiepolo style was viewed as passé before 1800. After Austrian troops annexed Venice under direction from Napoleon in 1796, Domenico retired to his country villa, and the Venetian painting tradition, like the republic itself, came to an end.

Additional resources:

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s Frescoes at the Wurzburg Residenz from artdaily.org

Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait

by DR. APRIL RENÉE LYNCH

There is an oft-quoted saying misattributed to Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France, during a famine suffered by her subjects: If they have no bread, “then let them eat cake.”

In fact, this statement (which showed flagrant disregard for the suffering of the people) was never uttered by the Queen that we know from so many sumptuous portraits. These portraits are largely the work of Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, a celebrated French artist known especially for her lavish portraits of Marie-Antoinette and other European monarchs and nobles as well as for her many self-portraits.

Patron Queen

Vigée-LeBrun first met Queen Marie-Antoinette at the royal palace at Versailles in 1778. The Queen had heard of the young painter’s successes and had her own likeness painted en robe a paniers (in a hoopskirt). The painting is a majestic full-length display of power. Marie-Antoinette stands facing the viewer, with the exception of her head, which is turned slightly to the viewer’s left so that she looks past us.The Queen is dressed in an elaborate golden white dress. Her hair is piled high and she wears a feathery headdress. All around her are the accoutrements of her station: huge columns, a marble bust of her husband, Louis XVI, displayed high atop a pedestal and behind a table on which sits a crown. The painting was originally meant for the queen’s brother, Emperor Joseph II of Austria, but Marie-Antoinette was so pleased with it that she ordered copies made for Catherine the Great of Russia and her own apartments at Versailles.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, painter

The artist who created this opulent showpiece became famous and wealthy as Queen Marie-Antoinette’s official court painter. She was born to Louis Vigée and Jeanne Maissin in a bustling section of Paris. In her autobiography Souvenirs written towards the end of her life, Vigée-LeBrun wrote that her father, a minor portraitist, doted on her, wishing his daughter fame and good fortune; and that he cherished her early efforts at drawing. Vigée-LeBrun wrote that her mother thought her awkward and ugly. Nevertheless, she grew up to be intelligent, beautiful, rich, and talented, characteristics on display in her Self-Portrait of 1790.

Created soon after her swift departure from France at the onset of the French Revolution, Vigée-LeBrun’s Self-Portrait in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, is one of her best-known pictures. It is a late example of the Rococo style. Rococo epitomized a fashionable ideal, wherein perpetual youth was libertine and pleasure-loving, its sexual gratification taken without guilt or consequence. Despite this, the artist, like her royal patron, was extremely conservative in her politics.

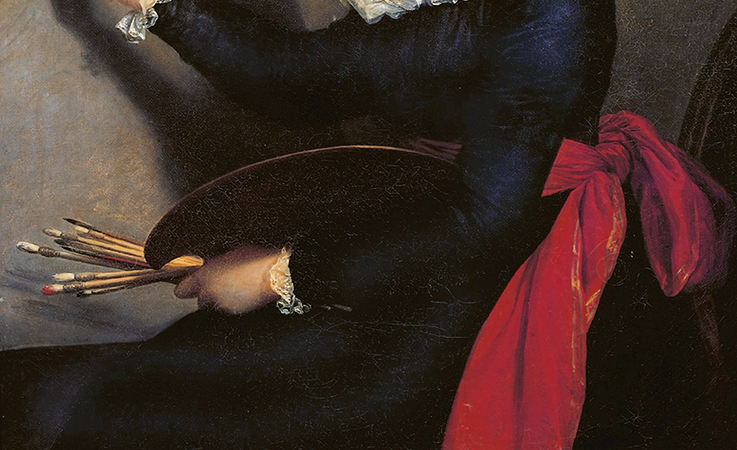

This self-portrait was painted in Rome; one of the first cities in which Vigée-LeBrun stayed during her decade-long exile from France. The artist sits in a relaxed pose at her easel and is positioned slightly off center. She wears a white turban and a dark dress—in the free-flowing style that Marie-Antoinette had made popular at the French court—with a soft, white, ruffled collar of the same material as her headdress. Her belt is a wide red ribbon. Vigée-LeBrun holds a brush to a partially finished work; the subject is probably Marie-Antoinette—perhaps intended as a tribute to her favorite sitter. Slightly used brushes are at the ready along with a palette, she has everything cradled in her arm close to the viewer.

The painting expresses an alert intelligence, vibrancy, and freedom from care. This, despite the fact that Vigée-LeBrun had been forced to flee France in disguise and under cover of darkness during the early stages of the Revolution. As she painted this portrait, her Queen was being driven from power by revolutionaries who hated the profligate lifestyle of the nobility and would later execute both Marie-Antoinette and her husband, King Louis XVI. Given these circumstances, Vigée-LeBrun—a working painter, wife, and mother—displays an extraordinarily sanguine persona.

Additional resources:

Gita May, Elisabeth Vigée-LeBrun: The Odyssey of an Artist in an Age of Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with her Daughter

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with her Daughter, Julie, 1789, oil on canvas, 130 x 94 cm (Musée du Louvre). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

During the course of her lifetime, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun painted many self-portraits, including her 1789 Self-Portrait with Her Daughter Julie (à l’Antique). In this intimate painting, she is seated on a bench as her daughter Julie leans into her body, and the arms of mother and daughter circle around each other. What differentiates this work from other self-portraits is her choice of attire. In this work, she appears to be wearing a one-shouldered dress that resembles the ancient Greek chiton, a garment not worn since antiquity. Why would the artist dress this way?

What is she wearing?

While other self-portraits by Vigée Le Brun show her wearing fashionable but modest dress (see for example her self-portrait from 1790), this garment exposes one shoulder and the upper chest area of her body. Although Vigée Le Brun wrote in her memoirs that she often “wore white dresses in muslin or linen lawn,” [1] she is not wearing an actual dress in this self-portrait, but one that has been formed from a length of white cloth wrapped over one shoulder and around her body. The cloth is held in place with a red scarf that is bound twice around her torso and fastened underneath her bust. A length of green silk is draped across her legs and a red ribbon is tied around her unpowdered hair. The artist’s considerable skill in rendering cloth is evident but there is another message intended by her choice of dress in this work.

Why would she dress this way for her self-portrait?

As a woman artist in eighteenth century France, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun had to work harder to gain access to the profession than a man with comparable skills, especially since women were not permitted access to life drawing classes. At the time, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) governed the profession of art in France, such that only members of the Academy had the right to publicly exhibit their work in the official salons. Although Vigée Le Brun was initially denied membership to the Academy, in 1783 the king of France ordered an exception be made and the artist became one of four female members.

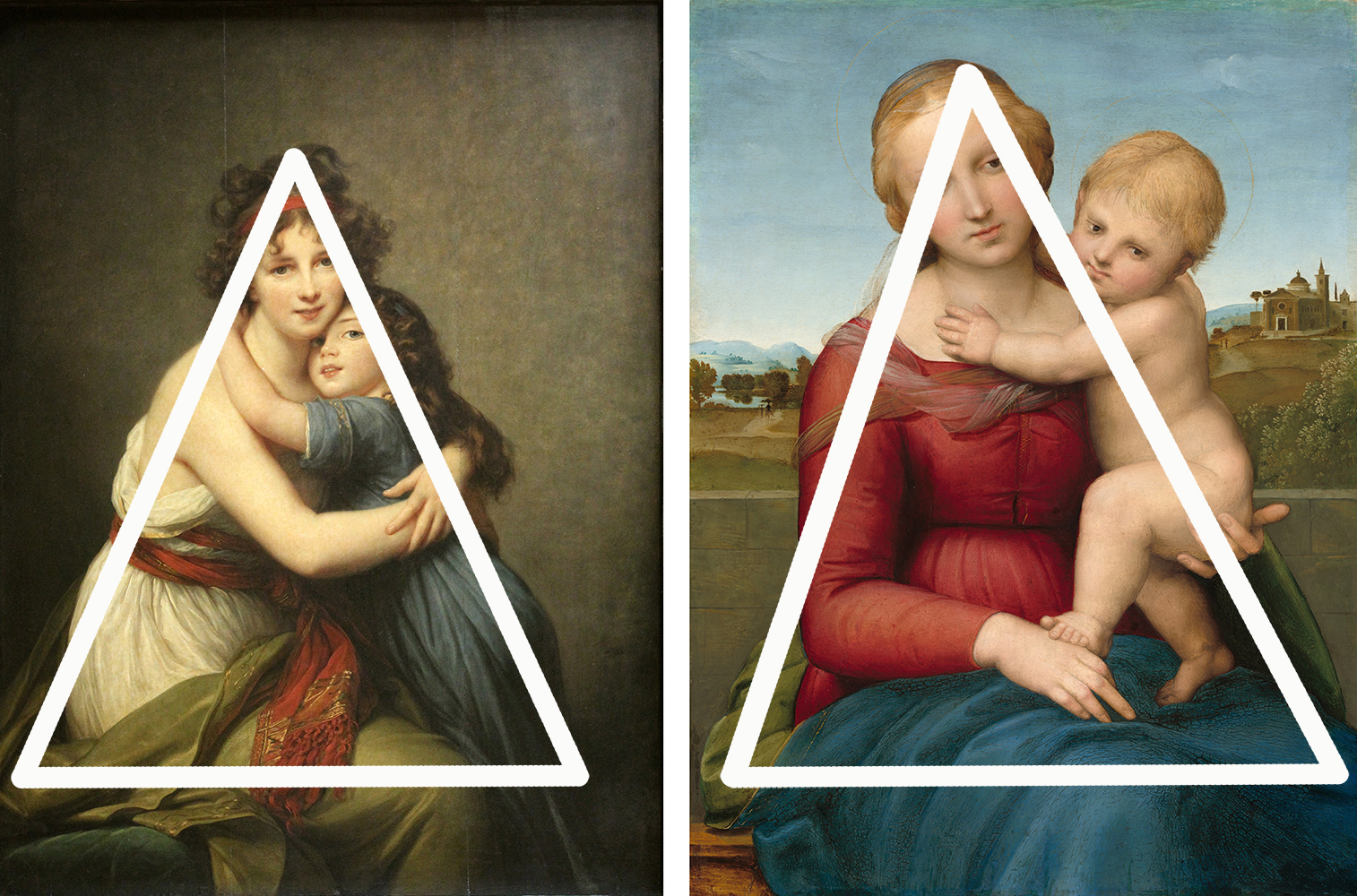

An artist’s self-portrait is a form of calling card that not only demonstrates skills in achieving a likeness but may also be designed to convey messages about the artist’s identity and inner life. Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s design of her 1789 self-portrait with her daughter echoes that of the Renaissance painter Raphael, a much-admired artist in eighteenth century France. Vigée Le Brun’s pose with her daughter creates a triangular composition that is reminiscent of Raphael’s Madonna and Child in The Small Cowper Madonna. In Raphael’s work, the arms of baby Jesus encircle his mother’s neck and the colours red, blue and green predominate. In addition, the manner in which the drapery falls across the lap in Le Brun’s work also seems to emulate Raphael.

Aside from the reference to Raphael, the draped cloth worn by Vigée Le Brun also creates a timeless quality that harkens back to the classical period. Although a more informal and lightweight type of long-sleeved dress was worn in the 1780s by women including the artist and her clients, the dress worn by the artist in this particular self-portrait is quite different from the the chemise á la reine. The garment worn by Vigée Le Brun in this work bares one shoulder and, in this way, closely resembles a chiton, a sleeveless and form-fitting dress created from draped cloth. Many examples of the chiton can be seen ancient Greek sculpture, including a marble statue of Aphrodite from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In creating a visual link to the classical era (ancient Greece and Rome) through her choice of dress, Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun may have wanted to reference legendary figures from that time. According to a Greek myth recounted by Pliny the Elder, the Corinthian maiden Dibutadis created the first drawing when she traced the shadow of her lover on a wall; this tale, in which the origin of drawing was linked to a desire to remember, was well known to artists in the eighteenth century. By wearing a form of dress linked to that time, Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun suggests that she is equally worthy of being remembered. Or she may have wanted the viewer to link her to the renowned painter Apelles of Kos from the fourth century B.C.E who Pliny the Elder considered superior to all other artists of the time. Either way, in dressing herself in a manner that is suggestive of classical antiquity, the artist invites viewers to equate her artwork to that of the artistic legends of the past.

Reading the clues of dress in a self-portrait

When an artist creates a self-portrait, they can choose to wear whatever they feel best reflects their identity. In reading such works, it is important to consider the fact that the artist’s choice of attire may or may not reflect what was actually worn at the time but instead be a deliberate reference to another artist and/or another time period. Such is the case in Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s Self-Portrait with Her Daughter Julie (à l’Antique) in which she references the classical period in her manner of dress in order to cast herself as equal to legendary masters from the past.

Notes:

- Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Memoirs of Madame Vigée-Lebrun, translated by Lionel Strachey, 1903 (London: Dodo Press, 2017), p. 42

Additional resources:

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Joseph Baillio, Katharine Baetjer, Paul Lang, Vigée Le Brun (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2016).

Ingrid E. Mida, Reading Fashion in Art (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).

Mary D. Sheriff, The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun and the Cultural Politics of Art (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1996).

Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Memoirs of Madame Vigée-Lebrun, Translated by Lionel Strachey, 1903. (London: Dodo Press, 2017).

Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, Madame Perregaux

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, Madame Perregaux, 1789, oil on oak panel, 99.6 x 78.5 cm (Wallace Collection, London)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jean-Honoré Fragonard

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767, oil on canvas (Wallace Collection, London)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love: The Meeting

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love: The Meeting, 1771-1773, oil on canvas, 317.5 x 243.8 cm (The Frick Collection, New York)

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Village Bride

by DANA MARTIN

A story of love

It is a simple story of love. We are transported to a rural country village to attend a wedding. The happy couple is in the center, their arms entwined in an obvious symbol of their love. The bride’s father, seated on the right, extends his arms in congratulations—he has just handed his new son-in-law his dowry.

The bride’s mother and younger sister caress her arm, sad to see her leave the family but very happy that she has found love. On the other hand, the older sister leans over her father’s shoulder to look on enviously and perhaps somewhat judgmentally, at her sister who has beaten her to the altar. The rest of the younger family members play nearby, accompanied by a few barnyard guests. With only a notary in attendance to make the marriage official, the ceremony can only be described as spare, and the French bourgeois public (or middle class) enthusiastically accepted Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s composition of humble simplicity.

A “natural” art

The Enlightenment is arguably one of the most radical moments in Western philosophical history, and while The Village Bride—a painting of a rural wedding—does not initially seem philosophical in subject, the age of the Enlightenment provides an important context for understanding the painting. Scholars questioned the traditions of Western culture, including the authority of the church and the arbitrary rule of the monarchy. Figures such as Denis Diderot attempted to compile all human knowledge into the first Encyclopédie. François Marie Arouet, who went by the name Voltaire, advocated for the advancement of science and technology. Yet none of these thinkers were as widely read as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (even the Queen Marie Antoinette was a fan). The famous introduction to his 1762 work The Social Contract, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains,” clearly states his philosophical concern. According to Rousseau, the customs of modern society—even its arts, sciences, and laws—have corrupted the inherent virtue and moral character of “natural” man. If we could throw off these self-imposed chains and return to a more natural state where emotion was respected, then compassion would replace tyranny and the alienation of the individual.

This idea of “natural” man led to a focus on an idealized view of rural, peasant life. Peasants, according to this line of reasoning, lived more simply, were closer to the earth and had not been corrupted by the forces of elite society. Further “natural” man was not ruled entirely by reason and logic—important signifiers of the modern world. Rousseau wrote, “To exist is to feel; our feeling is undoubtedly earlier than our intelligence, and we had feelings before we had ideas.”¹ With its depiction of a simple rural interior and the emotions of love, sadness, and joy, Greuze’s Village Bride encapsulates Enlightenment ideas of man—natural and uncorrupted.

Not a fête galante

Interest in the natural world had been central to the Rococo style since its inception earlier in the eighteenth century. We can see it, for example in the popular Rococo subject, the fête galante (typically a depicted the outdoor amusements of French upper-class society). Artists like Antoine Watteau created dreamy, romantic depictions like those of the young couples who have journeyed to the mythical island of love, Cythera (below).

Other Rococo artists like François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard were favorites of King Louis XV’s mistresses Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry, respectively. Each commissioned scenes of voluptuous, rosy-bottomed cupids and young lovers. These paintings were about pleasure and indulgence, and when compared to Greuze’s composition, The Village Bride becomes a commentary on aristocratic life. These fête galante love affairs are frivolous and lustful, while the actual marriages between various aristocrats was typically understood as a match made for political power, money, or convenience. In contrast, the couple that Greuze has given us is clearly the result of love. Here is a hard-working family with no power and little money, nevertheless rewarded for their virtuous love with happiness.

Professional success

Jean-Baptiste Greuze first achieved professional success in the Salon of 1755. His sentimental scenes found admirers among the upper middle-class public. At this time the art market had expanded beyond the wealthiest aristocracy, and a painting such a The Village Bride would have been a delight to the upper middle-class. It is easy to imagine the French public crowding around this painting, and discussing each pose and facial expression in detail. Greuze even found a fan in the philosopher, Denis Diderot, who remarked how difficult it was to even get close to the canvas because of the crowds. Greuze’s art would eventually fall out of style with the advent of Neoclassicism, but his paintings will always stand as a testament to the movement of natural man and moral philosophy.

- Jean-Jacque Rousseau, Emile, J.M. Dent and Sons: London, 1911, page 303.

Additional resources:

Greuze and his followers from The National Gallery of Art

Bernard II van Risenburgh, Writing table

The style of the French nobility

Encased in the curving frame and delicate decorative scheme of this writing table are clever innovations, technological and artistic brilliance, and a representation of completely new ways of living in the period beginning c. 1755.

After the formality and grandeur of Louis XIV’s Versailles, French aristocrats, including the king himself, were ready for spaces, furniture, clothing, and etiquette that allowed them to turn to matters other than the glorification of France. Beginning before the turn of the eighteenth century, but accelerated by the opportunity opened by the death of the Sun King in 1715, nobles set up their own homes after decades of living under the king’s enormous roof at Versailles, and created a radically different domestic life. Although it was only seven years until Louis XIV’s great-grandson was old enough to take the throne to reign as Louis XV, by 1722 new ideas of privacy, comfort, and intimate home life led to a new design language, the Rococo. All of the elements that are the basis for domesticity as we know it today were developed in this period.

A move away from Baroque grandeur and classicism

Louis XIV, during his long reign, had established France as a major European economic and political power, not least by the use of design as a strategic propaganda tool. Where the grandeur, drama, and theatricality of the Baroque, as Louis imported it from Rome, had been the perfect tool for portraying the King and his country as supremely powerful, by the early eighteenth century, the Baroque was starting to seem exhaustingly sumptuous. Baroque design was based on the classical language, which the earlier Renaissance artists had delighted in rediscovering, augmenting, and modifying. But by the early decades of the eighteenth century, designers were increasingly turning away from bombastic classicism to other sources, notably the natural world. They began playing with un-classical ideas like asymmetry, movement, linearity, sinuous curves, and realistic natural ornament. The Rococo, as it developed in design, was a sharp turn away from everything the Baroque had become.

Elegance, intimacy, delicacy and curves

Where Baroque spaces had been opulent, Rococo rooms were elegant. Grandeur became intimate delicacy. No less carefully designed or meticulously crafted, Rococo was light, fresh, and whimsical, to replace the heavy, fleshy Baroque. The lines of this writing table, as well as its applied ornament and its iconography, all express perfectly the Rococo sensibility. The piece is all curves, more vital and organic than architectural, with cabriole legs (with two curves) that seem to dance, and marquetry of ribbons, leaves and flowers. There’s no message here, no story told or idea conveyed, only pleasure and delight in an object for its own sake. Louis XV’s reign, like the man himself, was a time of lighthearted pursuit of beauty and sensual joie de vivre.

The artist

This table was designed by Bernard II van Risenburgh, one of a group of furniture makers working for Louis XV and his nobles. They produced new types of objects for new lifestyles, in the new Rococo design language, and using new technologies. Everything about this table is a fresh approach. Van Risenburgh was part of a relatively new guild of furniture specialists called ébénistes, who were responsible for the veneered skin of the piece only; the frame was built by a menusier. While many of the finest craftsmen of the eighteenth century worked only in the royal workshops, Van Risenburgh was unusual in having his own enterprise and selling primarily through retail middle-men known as marchand-merciers, a new-fangled concept. Furthermore, he signed his pieces (BVRB). In keeping with Enlightenment ideas of the eighteenth century which celebrated individuality and personal achievement, increasingly craftsmen were identifying themselves with their work. Van Risenburgh also designed his own gilt-bronze mounts, which created a distinct personal style and help to identify his work.

Tables were “in” (especially for women)

Tables were the delight of the new Rococo interior. Tiny moveable tables for ladies’ sewing, tables for playing cards, exquisite tables (bonheurs du jour) with porcelain plaques from the royal Sevres factory: an explosion of types and expressions. Writing, playing cards, correspondence were all fashionable amusements for the new world of the eighteenth century. Furthermore, small, highly detailed tables served as props for a particular kind of intimate domestic theater. Women especially used these objects in their expressions of themselves as cultured and sophisticated, skilled in the arts of polite society and seduction. A slender lace-clad wrist, lightly touching a hidden spring in a table, could reveal a drawer or a secret compartment, a book-rest, or in some pieces, all of these—in a series of carefully orchestrated steps. In the intimate aristocratic world of the early eighteenth century, women were the gatekeepers to the rooms where important men gathered, and thereby exercised great social and political power. For the first time, women chose and controlled their interiors, had their own objects, and interacted with them in a most self-conscious but seemingly insouciant way.

How it was used

This writing table gives the user some clues about how to employ it: first, there is an opening in the gilt-bronze (or ormolu) gallery (the little fence around the edge of the top) that tells where to sit. In accord with this positioning, one finds a pull-out flat writing surface with a leather inset, just below the table top. A drawer for storage slides out of one short end, and another flat surface pulls out of the other to create a place to put accessories such as ink and paper.

Not merely a piece of furniture, this writing table from the golden era of French design, is an indicator of great social changes, including changing women’s roles, stylistic shifts, and a personal relationship with objects that presaged the modern world as we know it today.

Additional resources:

DeJean, Joan E. The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual–and the Modern Home Began. New York: Bloomsbury, 2009.

Thornton, Peter. Authentic Decor: The Domestic Interior, 1620-1920. New York, NY, U.S.A.: Viking, 1984.

Whitehead, John. The French Interior: In the Eighteenth Century. London: L. King, 1992.