4.5: West Africa

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147761

West Africa

From rich textiles and elaborate masquerades to some of Africa's most well-known architecture.

13th century - present

About West Africa

by SMARTHISTORY

West Africa includes Benin, Burkina Faso, the Cape Verde Islands, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, the island of Saint Helena, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sao Tome, Principe and Togo.

Burkina Faso

Mask (Nwantantay) (Bwa peoples)

Among the southern Bwa peoples in Burkina Faso, large wooden plank masks are carved to represent various flying spirits that inhabit the natural world. These spirits, though largely invisible, are associated with water and can take physical form as insects that gather around a pool after a heavy rain or as a large water fowl, like an ibis. Some Bwa describe a mythological encounter in which a flying spirit appeared before a human, offering protection and service. A tall plank mask was created after this encounter to honor the spirit and ensure its continued beneficence.

This mask has a circular face and tall, vertical superstructure with a series of downward-curving hooks projecting from both the front and the back. The protruding, diamond-shaped mouth with jagged teeth is pierced to allow the wearer to see. Brightly painted patterns in red, black, and white enhance the bold geometric shape of the plank. These designs refer to important Bwa ideals of social and moral behavior that are taught over the course of initiation. Each symbol has multiple levels of meaning that older initiates reveal gradually to novices as they mature. The checkerboard pattern of black and white squares, for example, refers on one level to the animal skins on which people sit: white representing the clean, fresh hides assigned to youths and black suggesting the darkened skins owned by elders. On a less literal level, the juxtaposition of white and black squares suggests abstract concepts such as the separation of good from evil, and of light from dark.

Nwantantay masks are part of diverse ensembles of masks that represent animals, insects, humans, and supernatural creatures. The masks are commissioned and owned by large, extended families, or clans. The masks are used on several occasions throughout the year, including initiations, burials, annual renewal rites associated with planting and harvesting, and ceremonies celebrating the consecration of a new mask. These events are often competitive, with individual clans striving to present the most elaborate and inventive performance in the community. The mask is worn by a skilled dancer who secures it over his face by gripping a fiber rope on the mask’s back with his teeth. His body is concealed by a bushy fiber costume, traditionally dyed red or black, but now also seen in the bright green, yellow, and purple of European dyes. Accompanied by musicians playing flutes and drums and women singing songs, the masquerader moves rapidly, imitating the behavior of a flying spirit. With fiber costume twirling, he twists back and forth, then dips low to the ground, rotating the mask to suggest a disembodied apparition.

The tradition of carving and performing wooden masks is a recent one among the southern Bwa, adopted within the past hundred years from the neighboring Nunuma and Winiama peoples. Previously, the Bwa had created masks of leaves, vines, and grasses for use in ceremonies honoring Do, the earthly representative of the creator god. Resulting from the constant interplay of people and ideas, this example of cultural borrowing demonstrates the dynamism of masking traditions in the region and, in particular, the openness to innovation and adaptation that characterizes Bwa culture.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Christopher D. Roy, The art of Burkina Faso on Art & Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Do in Leaves and Wood Among the Bobo and the Bwa from Art and Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The art of Ghana

From Kente cloth to the metallic textiles of El Anatsui.

17th century - present

Golden Stool (Sika dwa kofi), Asante peoples

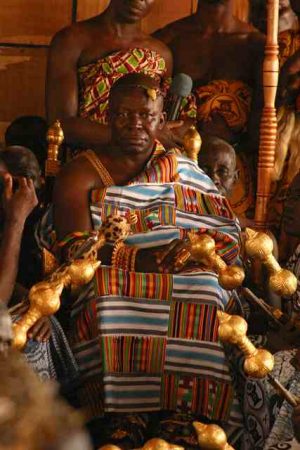

by DR. PERI KLEMM and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Golden Stool (Sika dwa kofi), Asante Peoples (Ghana), c. 1700 and Asante weights (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)

It took a miracle to bring this golden stool to Earth—and another one to keep it out of British hands.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Linguist Staff (Okyeamepoma) (Asante peoples)

This magnificent gold-covered staff was created to serve as an insignia of office for an okyeame, a high-ranking advisor to an Asante ruler. The position of okyeame encompasses a broad set of responsibilities, including mediation, judicial advocacy, political troubleshooting, and the preservation and interpretation of royal history. The okyeame’s most visible public role is as principal intermediary between the ruler and those who seek his counsel, leading to the popular characterization of his profession as being that of a linguist. Drawing upon vast knowledge and considerable oratorical and diplomatic skills, the okyeame eloquently engages in verbal discourse on behalf of the chief and his visitors. He relays the words of visitors to the king and transmits the king’s response, often with poetic or metaphorical embellishment.

Imagery on the finial of linguist staffs typically illustrates Asante proverbs about power and institutional responsibilities. Here, a spider on its web is flanked by two figures, representing the proverb: “No one goes to the house of the spider to teach it wisdom.” The spider is a fitting symbol for respect due to a person with great oratorical and diplomatic skills. In Ghana, Ananse the spider is the bringer of the wisdom of Nyame, the supreme creator god of the Asante, and is the originator of folk tales and proverbs. The staff is composed of a long wooden shaft carved in two interlocking sections and a separate finial attached to the base. It is covered entirely with gold foil, a material that alludes to the sun, and to the vital force or soul contained within all living things.

Although the institutional office of okyeame is believed to be centuries old, the use of figural wooden linguist staffs as insignia is probably a more recent development. Prior to the late nineteenth century, linguist staffs took the form of a simple cane, a tradition likely borrowed from European prototypes in the mid-seventeenth century. During the late nineteenth to early twentieth century, the British gave official staffs, often made with figural finials, to Akan chiefs who represented the colonial authorities. Since 1900, hundreds of figural linguist staffs have been carved not only for linguists but also for representatives of other institutions, such as associations of fishermen, carpenters, and musicians.

The Asante kingdom, part of the larger Akan culture, was formed around 1700 under the leadership of Osei Tutu. Osei Tutu brought together a confederation of states that had grown wealthy and powerful as a result of the area’s lucrative trade in gold, sold to both northern merchants across the Sahara and European navigators. The centralized system of government that emerged was a complex network of chiefs and court officials under a single paramount leader. A variety of gold regalia was used to distinguish rank and position within the court.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Art of the Asante Kingdom on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Gold in Asante Courtly Arts on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

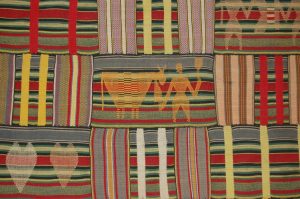

Kente cloth

Inspired by a spider’s web

Among the Asante (or Ashanti) people of Ghana, West Africa, a popular legend relates how two young men—Ota Karaban and his friend Kwaku Ameyaw—learned the art of weaving by observing a spider weaving its web. One night, the two went out into the forest to check their traps, and they were amazed by a beautiful spider’s web whose many unique designs sparkled in the moonlight. The spider, named Ananse, offered to show the men how to weave such designs in exchange for a few favors. After completing the favors and learning how to weave the designs with a single thread, the men returned home to Bonwire, and their discovery was soon reported to Asantehene Osei Tutu, first ruler of the Asante kingdom. The asantehene adopted their creation, named kente, as a royal cloth reserved for special occasions, and Bonwire became the leading kente weaving center for the asantehene and his court.

A royal cloth

Originally, the use of kente was reserved for Asante royalty and limited to special social and sacred functions. Even as production has increased and kente has become more accessible to those outside the royal court, it continues to be associated with wealth, high social status, and cultural sophistication. Kente is also found in Asante shrines to the deities, or abosom, as a mark of their spiritual power.

Historians maintain that kente cloth grew out of various weaving traditions that existed in West Africa prior to the formation of the Asante Kingdom. These techniques were appropriated through vast trade networks, as were materials such as French and Italian silk, which became increasingly desired in the 18th century and were combined with cotton and wool to make kente.

Kente cloth is also worn by the Ewe people, who were under the rule of the Asante kingdom in the late 18th century. It is believed that the Ewe, who had a previous tradition of horizontal loom weaving, adopted the style of kente cloth production from the Asante—with some important differences. Since the Ewe were not centralized, kente was not limited to use by royalty, though the cloth was still associated with prestige and special occasions. A greater variety in the patterns and functions exist in Ewe kente, and the symbolism of the patterns often has more to do with daily life than with social standing or wealth.

Weaving kente

Kente is woven on a horizontal strip loom, which produces a narrow band of cloth about four inches wide. Several of these strips are carefully arranged and hand-sewn together to create a cloth of the desired size. Most kente weavers are men.

Weaving involves the crossing of a row of parallel threads called the warp (threads running vertically) with another row called the weft (threads running horizontally). A horizontal loom, constructed with wood, consists of a set of two, four or six heddles (loops for holding thread), which are used for separating and guiding the warp threads. These are attached to treadles (foot pedals) with pulleys that have spools of thread inserted in them. The pulleys can be used to move the warp threads apart. As the weaver divides the warp threads, he uses a shuttle (a small wooden device carrying a bobbin, or small spool of thread) to insert the weft threads between them. These various parts of the loom, like the motifs in the cloth, all have symbolic significance and are accorded a great deal of respect.

By alternating colors in the warp and weft, a weaver can create complex patterns, which in kente cloth are valued for both their visual effect and their symbolism. Patterns can exist vertically (in the warp), or horizontally (in the weft), or both.

A cloth with a name

Patterns each have a name, as does each cloth in its entirety. Names are sometimes given by weavers who obtain them through dreams or during contemplative moments when they are said to be in communion with the spiritual world. Alternatively, chiefs and elders may ascribe names to cloths that they specially commission. Names can be inspired by historical events, proverbs, philosophical concepts, oral literature, moral values, human and animal behavior, individual achievements, or even individuals in pop culture. In the past, when purchasing a cloth, the aesthetic and social appeal of the cloth’s was as important as—or sometimes even more important than—its visual pattern or color.

This cloth is named The King Has Boarded the Ship, and it includes both warp and weft patterns. The warp pattern, consisting of two multicolor stripes on blue, relates to the proverb “Fie buo yE buna,” meaning the head of the family has a difficult task. The weft patterns vary throughout the cloth; these examples are “NkyEmfrE,” a broken pot, and “Kwadum Asa,” an empty gunpowder keg.

Wearing kente

There are differences in how the cloth is worn by men and women. On average, a men’s size cloth measures 24 strips wide, making it about 8 feet wide and 12 feet long. Men usually wear one piece wrapped around the body, leaving the right shoulder and hand uncovered, in a toga-like style. Women may wear either one large piece or a combination of two or three pieces of varying sizes ranging from 5-12 strips, averaging of 6 feet long. Age, marital status, and social standing may determine the size and design of the cloth an individual would wear.

Social changes and modern living have brought about significant changes in how kente is used. It is no longer only the privilege of royalty; anyone who can afford it can buy kente. The old tradition of not cutting the cloth has also long been set aside, and it may be sewn into other forms such as dresses, shirts, or shoes. Printed versions of kente are mass produced and marketed, and both woven and printed versions are used by fashion designers in Ghana and abroad.

Kente is more than just a cloth. It is an iconic visual representation of the history, philosophy, ethics, oral literature, religious belief, social values, and political thought of West Africa. Kente is exported as one of the key symbols of African heritage and pride in African ancestry throughout the diaspora. In spite of the proliferation of both the hand-woven and machine-printed kente, the design is still regarded as a symbol of social prestige, nobility, and cultural sophistication.

Additional resources:

Videos of kente weaving: Kente Weavers of Asante, Bonwire Kente, Bonwire Kente weavers

“Wrapped in Pride” from the National Museum of African Art

“Asante Textile Arts” from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Memorial Head (Akan peoples)

Since the late sixteenth century, Akan women potters have created ceramic heads and sometimes complete figures to commemorate deceased royals and individuals of high status. During the funeral, family members placed the terracotta portraits of the deceased in a sacred grove near the cemetery, sometimes with representations of other family members. These sculptures served as the focal point for funerary rites in which libations and food were offered to the ancestors.

This example has a rounded face with protruding elliptical eyes that tilt downward and a delicately shaped nose. These circular shapes are repeated by the eyebrows, ears, and open, oval-shaped mouth which projects from the smooth surface of the face. An incised line curves around the forehead, indicating the hairline. The surface of the sculpture has been covered with a clay slip tinted black, a color linked to the ancestral world and spiritual power in Akan thought.

Like other examples of African portraiture, these commemorative sculptures are idealized representations that convey individuality through specifics of scarification and hairstyle. The artist would typically be summoned to the deathbed of the deceased in order to observe his or her distinguishing characteristics, which she would depict later, working from memory to capture the individual’s essence. The figural terracotta sculptures vary enormously in style, ranging from fairly naturalistic and sculpturally rounded forms to examples that are solid, flat, and more dramatically stylized.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ghana on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Akua’ba Female Figure (Akan peoples)

by DR. PERI KLEMM

According to Akan myth, in the distant past a woman named Akua could not conceive. Akua sought first the spiritual reason for her infertility. She went to a diviner. He told her to commission a carver to create for her a wooden child and to care for that child as though it were her own. Akua did as she was told and within a few months, she conceived.

Among the Akan peoples, women who had trouble becoming pregnant might utilize one of these figures in the same way Akua did, if a diviner—after ritual prophecy—ascertained that it might be helpful. A carver would then create a figure for her and she would carry it on her back, offer it symbolical food and drink, and honor it on a shrine in her home until she conceived a child (ba). The figure could be gifted to another female family member if she, too, sought spiritual help to bear a child.

Akua’ba figures were important fertility aids among Akan-speakers in Ghana in the past. They depict an abstracted female form in wood and were created by male carvers.

While this figure is called Akua’ba (Akua’s child), it is clearly not meant to resemble a child. Rather, it depicts a highly abstracted and idealized woman in the prime of life (example above left). African art almost always depicts figures in their prime. This time, just after puberty, when young people are generally healthy, strong, initiated, and fertile, is when humans are most ripe with potential—they have the knowledge to successfully pursue adulthood and the physical maturation to marry and procreate. For new parents, this is the stage one hopes for one’s child, especially since high infant and childhood mortality rates remain a formidable reality. The figure is also always female, since Akan culture is matrilineal.

While meant to convey the prime of life, the akua’ba is also quite abstract. Her body has been reduced to a tubular form with small arms, a ringed neck, and a large, flat head. Some akua’ba also have a rectangular head and more recent forms include a more naturalistic body (example right). By emphasizing certain features, the artist has communicated the Akan ideal of female beauty. Her large, rounded forehead, understood as the place where knowledge resides, suggests the wealth of knowledge and intellectual maturity this child should have. Her ringed neck is intended to denote rolls of fat. Extra body fat at this lifecycle state suggests that the young woman is full-figured and capable of baring healthy children. Lastly, her high, protruding breasts suggest a woman who has not yet bore and nursed children. The akua’ba therefore demonstrates three important qualities of womanhood (wisdom, girth, and the prime of life) that relate to her physical and mental abilities.

Due to their unique look and portable size, akua’ba figures have become marketable tourist items and are now part of the Western visual vocabulary. Images of akua’ba have become generalized icons of Africa in commercial settings and it is common to find them depicted in jewelry, greeting cards, print ads and mass media (one is featured on the mantel of the television sitcom Will and Grace). Taken out of the Akan context, altered by Western tastes (which might add beads and paint), and marketed as a universal symbol of Africa, the akua’ba figure is now part of Western popular culture.

Additional resources:

Akua’ba on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Asafo Flags: Stitches Through Time

by HENI TALKS

Gus Casely-Hayford - Asafo Flags: Stitches Through Time from HENI Talks on Vimeo.

Gus Casely-Hayford traces the history of Asafo Flags, unique textiles from Ghana. He draws upon his own personal and historical perspectives to help us understand the lasting relevance of these cultural artefacts.

Featuring national symbols alongside local motifs, Asafo Flags conjure a vibrant past. Whilst flagging familial identity, they also served to signal existing military allegiances with arriving European forces in the 16th century. In ‘a glorious defiance against time’, these flags provide ‘a visual metaphor for what community could mean.’

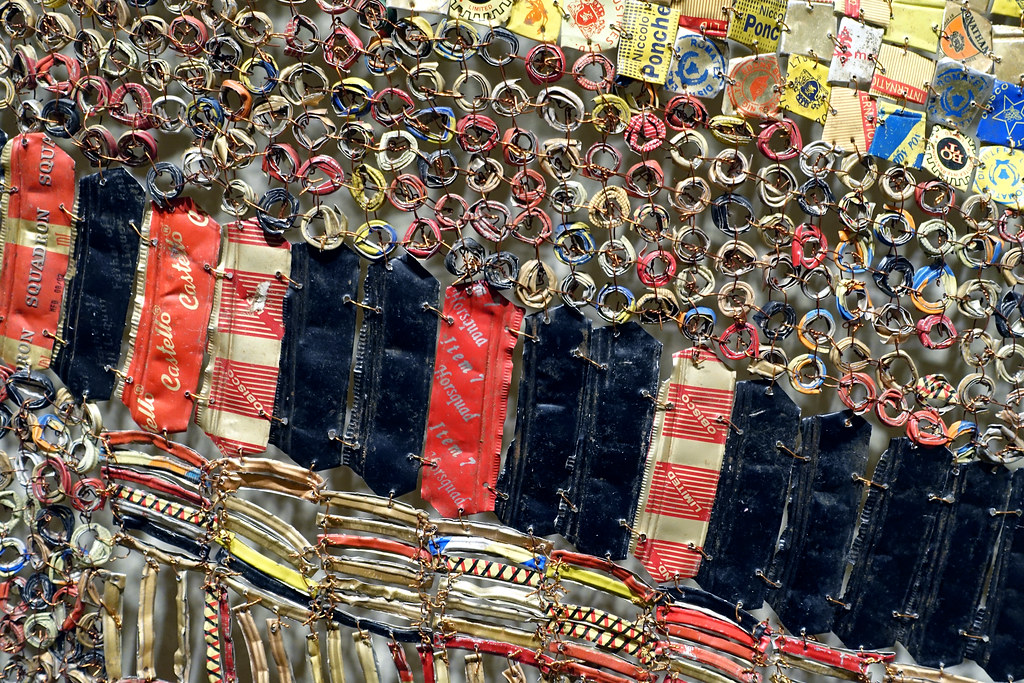

El Anatsui

El Anatsui, Untitled

by DR. PERI KLEMM and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): El Anatsui, Untitled, 2009, repurposed printed aluminum, copper, 256.5 × 284.5 × 27.9 cm as installed (Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington D.C.)

The artist transforms metal from alcohol bottles into textiles that represent libations for ancestors.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

El Anatsui, Old Man’s Cloth

Old Man’s Cloth hangs like a large tapestry, but when we look closer, it’s easy to become captivated by the small metal fragments that comprise the work in hundreds. Arranged within a shifting grid of stripes and blocks of color, the components form their own internal maps across the surface, melding into vertical gold bands, interlocking black and silver rows, or a deviant red piece floating in a field of black. While Old Man’s Cloth would have been laid flat during its construction, it is contorted and manipulated during installation, so that the individual metal pieces can catch the light from every angle. This brilliant visual effect makes its humble origins all the more impressive.

The Medium or the Message?

Old Man’s Cloth has been constructed from flattened liquor bottle labels that the artist collects near his home in Southern Nigeria. While critics often write about Anatsui’s metal wall hangings using the language of textiles, the labels and bottle caps are typically fastened together with copper wire and attached corner-to-corner. As such, the issue of medium is one of the first to inspire debate amongst viewers—are the wall hangings two-dimensional or three-dimensional? Are they sculptures, even as they hang against the wall like paintings? Are they individual works or immersive installations? Lastly, are they “fine art” or simply an innovative form of “craft”?

Purposefully disregarding the limited categories imposed by Western art history, Anatsui’s practice emerges from a more expanded understanding of what art can be that stems from both the radical practices of the late-1960s, and from a vantage point outside of the Western tradition completely. As scholar Susan Vogel has explained, “such categories did not exist in classic African traditions, which made no distinction between art and craft, high art and low.”

Anatsui’s choice of discarded liquor bottle caps as a medium has as much to do with their formal properties as with their historical associations. As an African artist whose career was forged during the utopia of mid-century African independence movements, his work has always engaged his region’s history and culture. The bottle caps, for Anatsui, signify a fraught history of trade between Africa and Europe. As he explained,

Alcohol was one of the commodities brought with [Europeans] to exchange for goods in Africa. Eventually alcohol become one of the items used in the transatlantic slave trade. They made rum in the West Indies, took it to Liverpool, and then it made its way back to Africa. I thought that the bottle caps had a strong reference to the history of Africa.

The luminescent gold colors also recall the colonial past of Anatsui’s home country—modern Ghana was previously a British colony called The Gold Coast until its independence in 1957. The fluid movements of the work’s surface remind us of the waters of the Atlantic Ocean, which carried slave-ships and traders between Africa, Europe and the New World. By bestowing his works with titles such as Man’s Cloth and Woman’s Cloth, Anatsui also makes reference to the significance of textiles in African societies, and their own historical role in trade networks.

Old Man’s Cloth was included in one of Anatsui’s first exhibitions of hanging metal sculptures. Held at London’s October Gallery in 2004, the show was entitled “Gawu,” which means “metal cloak” in Ewe. Old Man’s Cloth is unique for its uneven and jagged edges as well as the “rough texture” of the recycled labels that are incorporated into the piece.

Modernism in Africa

El Anatsui was born in Ghana in 1944, and was trained in an academic European curriculum. In 1964, when he began his studies, many parts of Africa were experiencing a cultural renaissance associated with decolonization movements. Anatsui himself joined the unofficial “Sankofa” movement, which was invested in unearthing and reclaiming Africa’s rich indigenous traditions and assimilating these with the European-influenced aspects of society. His earliest works, for example, included a series of wooden market trays into which he burned designs inspired by African graphic systems and adinkra motifs (symbols widely used by the Akan people of Ghana).

In 1975, Anatsui joined the faculty at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Nsukka was a vibrant creative capital for African artists and writers in the 1970s, many of whom spearheaded the Zaria Rebellion in the early 1960s and revived the traditional art form of uli wall and body painting in their contemporary works.

Anatsui’s work differed slightly from that of his colleagues in his insistence on abstraction. In some of his first mature works, he used an electric chainsaw to slash geometric patterns into wood. Though abstract, these works were metaphorically rich; Anatsui chose woods of different colors to represent the diversity of African cultures, while the violence of the chainsaw enacted the ruptures imposed by European imperialist expansion.

Critical Reception: African or Contemporary?

When two of Anatsui’s metal wall hangings appeared in the 2007 Venice Biennale, they were lauded by the public and swiftly cemented his place as a leading international contemporary artist. He had, in fact, already shown in Venice almost two decades earlier in 1990, when he participated in a small exhibition surveying contemporary African art. During the time that lapsed between the two exhibitions, the art world became more receptive to artists outside of its Western centers, and by 2007, Anatsui could exhibit not only as a representative of the continent, but as an individual artist whose work was significant in its own right.

As such, his work provides an excellent opportunity for discussion about the relationships between artists at the center and at the periphery, and between the West and the Global South. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for instance, has now acquired two of Anatsui’s metal wall hangings, but they are owned by two different curatorial departments: the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas, and Modern and Contemporary Art. Both were recently on view at the same time, but in separate galleries. Visitors, students, and art historians should continue to ask themselves which designation seems more appropriate, and for what reasons. Should we understand his art as a product of its place, its time, or both? What do we see in Anatsui’s work when it is placed among African masks and ritual objects, and how do our impressions change when this work is placed beside contemporary art from around the world?

There are no correct answers to these questions, but they are indicative of the changes that have taken place both in the art world, and in today’s increasingly connected society at large.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Guinea

Headdress: Female Bust (D’mba)

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): D’mba mask (Baga peoples, Guinea), 19th-20th century, wood, 118.1 x 35.3 x 67.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Speakers: Dr. Peri Klemm and Dr. Beth Harris

This massive headdress is an example of a regional artistic tradition that dates to at least 1886 and possibly to the early seventeenth century. Among Baga subgroups the headdress is referred to variously as D’mba or Yamban, an abstract concept personifying local ideals of female power, goodness, and social comportment.

Carved from a single piece of wood, this work takes the form of a large head and slender neck supported by a yoke with four projecting legs. Flat, pendulous breasts signify that the subject is a mature woman who has nursed many children. She is distinguished from ordinary Baga by her intricately braided coiffure with high central crest, a hairstyle associated with Fulbe women, who are renowned for their physical beauty. This coiffure is also a reminder of cultural origins, as the Fulbe live in the Futa Jallon mountains, the ancestral homeland of the Baga people.

Incised linear patterns representing scarification marks decorate her face, neck, and breasts. Such monumental structures, carried on the shoulders of the performer, often weigh more than eighty pounds. In its original context, the headdress would have had a thick raffia skirt attached to the bottom of the yoke. A shawl of dark cotton cloth, imported from Europe, would be tied around the shoulders, hiding the legs of the yoke.

The ideals of womanhood expressed symbolically by the strong forms of the headdress are reinforced by the movement of the male dancer, who communicates a model of virtuous behavior for Baga women. Performances documented in the 1990s describe the dramatic entrance of the masquerader in a central plaza, preceded by a processional line of drummers. Despite its unwieldy size, the headdress is manipulated skillfully by the dancer, whose movements are alternately composed and vigorous. As the dancer twirls to the accompaniment of drums, the assembled audience of male and female onlookers participates actively. Some reach to touch the breasts of the headdress, affirming its blessings of fertility, while others throw rice, symbolizing agricultural bounty. Songs prescribing proper social behavior are led by women who are joined in the chorus by men. Beginning at sunrise, the celebration continues through sundown and sometimes over the course of many days.

Historically, such masks were used in dances held at planting times and harvest celebrations, as well as at marriages, funerals, and ceremonies in honor of special guests. Following Guinea’s independence from France in 1958 and its adoption of a Marxist government, the tradition was suppressed by Muslim leaders and state officials. In the 1990s, the lifting of decades of censorship was followed by a popular revival of earlier art forms. In Baga society, D’mba (or Yamban) now appears publicly on occasions marking personal and communal growth, including marriages, births, and harvest festivals, as well as celebratory occasions such as soccer tournaments.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

The art of the Ivory Coast

To the Baule people, sculpture serves many functions and these can shift over time and within different contexts.

19th - 20th century

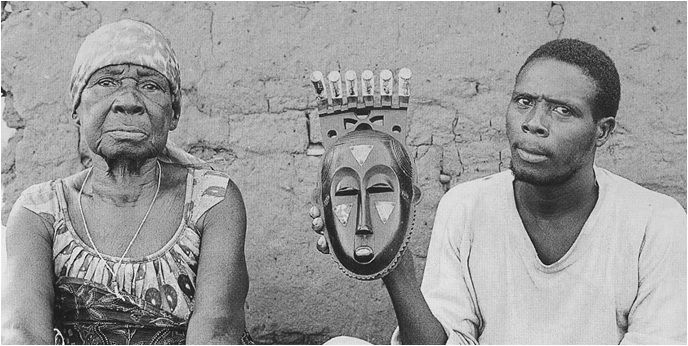

Owie Kimou, Portrait Mask (Mblo) of Moya Yanso (Baule peoples)

by DR. PERI KLEMM

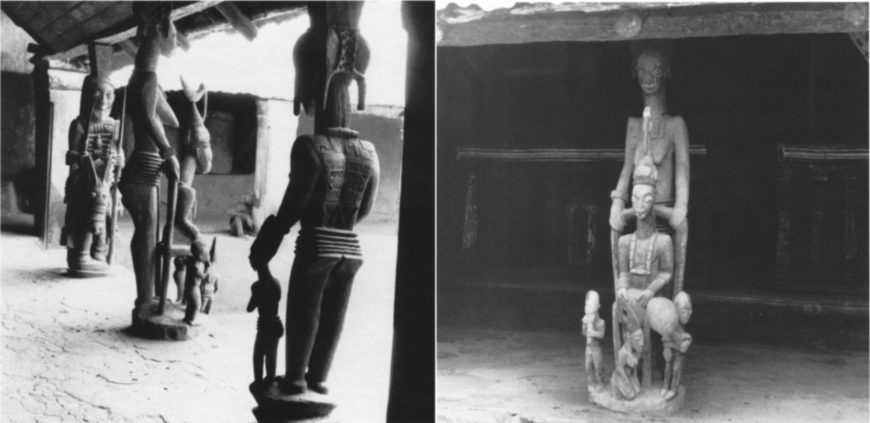

The 400,000 Baule who live in central Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa have a rich carving tradition. Many sculpted figures and masks of human form are utilized in personal shrines and in masquerade performances. This mask was part of a secular masquerade in the village of Kami in the early 1900s.

Masquerade

The Baule recognize two types of entertainment masks, Goli and Mblo. To perform a Mblo mask, like the one depicted, a masker in a cloth costume conceals his face with a small, wooden mask and dances for an audience accompanied by drummers, singers, dancers, and orators in a series of skits. In the village of Kami, the Mblo parodies and dances are referred to as Gbagba. When not in use, the Gbagba masks were kept out of sight so it is unusual that we get to see a mask displayed in this manner.

To the Baule, sculpture serves many functions and these can shift over time and within different contexts. The Gbagba masquerade is a form of entertainment no longer practiced in Kami since the 1980s, replaced today by newer masks and performance styles. What is known, however, is that masks like this one were not intended to be hung on a wall and appreciated, first and foremost, for their physical characteristics. Sculpture throughout West Africa has the power to act; to make things happen. A carving of a figure, for example, can be utilized by practitioners to communicate with ancestors and spirits. The physical presence of a mask can allow the invisible world to interact with and influence the visible world of humans. Scholar Susan Vogel mentions that Gbagba could bring social relief at the end of a long day and respite from everyday chores. It allowed residents to socialize, mourn, celebrate, feast, and even, court.[1]

Moya Yanso

In the case of this Gbagba mask, Vogel tells us that it was meant to honor a respected member of Baule society. This mask is unusual. Most older African carving come into Western collections without information about the artist or subject, but in this case, both the carver and the sitter have been recorded. In the photograph below we see an older woman seated next to the portrait mask. She is Moya Yanso and this is her image carved by a well-known Baule artist, Owie Kimou. The man holding the mask is her stepson who danced this mask in a Gbagba performance. It was commissioned and originally worn by Kouame Ziarey, Moya Yanso’s husband and later his sons. Revered as a great dancer, Moya Yanso accompanied the mask in performances throughout her adult life until she was no longer physically able. This portrait mask tradition came to end in the early 1980s with the decline of Gbagba and while entertainment masks continue, they are no longer carved to represent specific individuals.

Portrait masks characteristically have an oval face with an elongated nose, small, open mouth, downcast slit eyes with projecting pieces that extend beyond the crest to suggest animal horns. Most also have scarification patterns at the temple and a high gloss patina. These stylistic attributes are actually a visual vocabulary that suggests what it means to be a good, honorable, respected, and beautiful person in Baule society. The half slit eyes and high forehead suggest modesty and wisdom respectively. The nasolabial fold depicted as a line between the sides of the nose to the outsides of the mouth and the beard-like projecting triangular patterns that extends from the bottom of the ears to the chin, suggest age. The triangular brass additions heighten the lustrous patina when danced in the sunlight, a suggestion of health.

An Ideal

The hairstyles of portrait masks are known to be quite realistic but other features, like the six projecting tubular pieces at the crown, are abstract. This is not a realistic representation of the woman in the photograph, rather, it suggests an idealized inner state of beauty and morality associated with Moya Yanso.

Notice that Moya Yanso’s portrait mask is in the hands of her stepson in the photograph. Masking is the prerogative of men. While women attend masquerades as audience members and can perform with masked dancers, they do not wear or own masks themselves. The performers and makers of masks as well as those who commission them are always men.

From West Africa to the Midwest

It is interesting to note the way in which African objects gather value in the West. This mask was acquired from the family of Moya Yanso in 1997 by a collector in Brussels, then sold to a French collector, and finally sold through the Sotheby’s auction house in 1999 for 197,000 US dollars to a collector in Minneapolis. The mask has also been exhibited at the Yale University Art Gallery, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum for African Art in New York. It is featured on the front cover of Baule: African Art, Western Eyes (1997) by Susan Vogel, who has written extensively on Baule art and first conducted fieldwork in Kami village in the 1960s.

For many collectors in the West, it is the formal properties of the mask that are alluring. Like the avant-garde artists in the early 20th century who were looking for new stylistic avenues to represent the modern condition, collectors today value the abstract qualities of Baule art. Vogel aptly notes that “Baule believers first encounter the object’s indwelling spiritual powers, or the metaphysical ideas it evokes, while the connoisseur begins with the visible forms, colors, textures—the artist’s material creation.”[2] Among the Baule up to the 1970s, this mask would remain hidden unless performed with musicians and dancers. To separate this mask from its masquerade is to give it new life as aesthetic object.

[1] Susan M. Vogel, Baule: African Art, Western Eyes, New Haven, 1997, p. 140

[2] Vogel, p. 18

Additional resources

Ravenhill, P. “Likeness and Nearness: The Intentionality of the Head in Baule “Art,“ African Arts, 33(2), 2002.

Susan M. Vogel, Baule: African Art, Western Eyes, New Haven, 1997.

Susan M. Vogel, “Known Artists but Anonymous Works: Fieldwork and Art History”, African Arts, Vol. 31(1), 1999.

Sotheby’s Auction Catalogue

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Pair of Diviner’s Figures (Baule peoples)

Carved by the same hand, these figures reflect and embody Baule ideals of civilized beauty. In Baule society, diviners commission such figures from artists to attract the attention of asye usu, or nature spirits. Asye usu are considered to be grotesque and volatile beings associated with the untamed elements of nature. The spirits are seduced from the wilderness by the figures’ dazzling beauty and lured into inhabiting the sculptures, which embody the civilized values the asye usu lack and therefore find so desirable. The asye usu are then induced into sharing spiritual insights, conveyed through the medium of the diviner.

Such figures are prominently displayed during ritual sessions with clients who seek clarification about their difficulties, which can range from poor harvests to physical illness. The presence of the sculptures and the sacrificial material applied to their feet (never to the smooth surfaces of their bodies), along with repeated striking of a gong, help to induce the trance state that allows the diviner to communicate with the asye usu. The diviner can then gain insights and revelations regarding the source of the client’s problems. The ownership of such extraordinary works also serves to further the professional standing of the diviner, who must impress potential clients with the caliber and sophistication of the instruments used in his or her practice.

Although depicted separately, the male and female figures are perfectly harmonized through their matched forms, gestures, stances, and expressions. Their elaborate coiffures, intricate scarification, and beaded accoutrements signify cultural refinement and status. Their erect, balanced pose and partially closed eyes imply respect, self-control, and serenity. The fully rounded muscles of their flexed legs suggest physical strength, youthful energy, and the potential for action. White kaolin accentuates the elegant arches of their eyebrows, reflecting the practice of diviners, who apply the fine clay around their eyes to facilitate communication with the spirits.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The art of Mali

The art of Mali takes many diverse forms, but it all celebrates the bonds of the communities that create it.

13th century - present

Saving Timbuktu’s manuscripts

by FATHER COLUMBA STEWART, OSB and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): A conversation with Father Columba Stewart, OSB, executive director of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (Collegeville, Minnesota) and Dr. Beth Harris

A heroic effort to save and preserve Mali’s long manuscript tradition.

Seated Figure (Djenné peoples)

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Seated Figure, terracotta, 13th century, Mali, Inland Niger Delta region, Djenné peoples, 25/4 x 29.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), 82nd & Fifth: “Bundle of Emotions” by Yaëlle Biro.

Among the earliest known examples of art from sub-Saharan Africa are terracotta figures like this one from the inland delta of the Niger River, near the present-day home of the Dogon and Bamana peoples.

In this region of Mali, the ancient city of Jenne-jeno (“Old Jenne”) flourished as a center for agriculture, trade, and art from the middle of the first millennium until about 1600. The terracotta figures associated with this civilization represent men and women, singular and in pairs, in a variety of attire and poses, including sitting, kneeling, and on horseback. The diversity of imagery and the skill with which they were modeled reveal the rich sculptural heritage of a sophisticated urban culture.

This figure sits, hunched over, with both arms clasping an upraised leg, its head tilted sideways to rest against its bent knee. The posture evokes a pensive attitude that is reinforced by the expressiveness of the facial features: the bulging eyes, large ears, and protruding mouth are all stylistically characteristic of works from this region.

The fluid contours of the body emphasize the long sweeping curve of the neck and back and the rhythmic play of intertwined limbs. Except for the barest suggestion of shoulder blades, fingers, and toes, the figure lacks anatomical details. On the back are three rows of raised marks and two rows of marks punched into the clay. These have been variously interpreted as scarification marks or symptoms of a disease.

Thermoluminescence tests indicate that this figure was fired during the first half of the thirteenth century. Other terracotta figures recovered (and, in many cases, looted) from various sites throughout the Inland Niger Delta have been dated from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century. Artists—either men or women—modeled the figures by hand, using clay mixed with grog (crushed potsherds). Details of dress, jewelry, and body ornament were either added on or incised. Once complete, the work was polished, covered with a reddish-toned clay slip, and then fired, probably in an open-pit kiln.

The surviving figures vary in style and subject matter, suggesting that the sculptors had considerable artistic freedom. Our understanding of the use and meaning of such works remains speculative. A few controlled archaeological digs have revealed similar figures that were originally set into the walls of houses. Oral history collected recently in the region supports the archaeological evidence, as the figures are said to have been venerated in special sanctuaries and private homes. There is little consensus, however, on the meaning of the various forms of the terracotta figures. Scholars have suggested that this figure conveys an attitude of mourning. Its seated pose, shaved head, and lack of dress recall mourning customs still practiced by some in this region of western Africa.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

Explore this object—360 view, from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Neil Brodie & Donna Yates, “Nok Terracottas” on Trafficking Culture

Holland Cotter, “Imperiled Legacy for African Art,” The New York Times (August 2, 2012)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Lost History: the terracotta sculpture of Djenne Djenno

by DR. KRISTINA VAN DYKE and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Seated figure, 13th century, Mali, Inland Niger Delta (Djenné peoples), terracotta, 25.4 x 29.9cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Speakers: Dr. Kristina Van Dyke and Dr. Steven Zucker

Are these little-understood figures representations of diseased people, or an attempt to ward off illness?

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Djenné on Art and Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Great Mosque of Djenné (Djenné peoples)

As one of the wonders of Africa, and one of the most unique religious buildings in the world, the Great Mosque of Djenné, in present-day Mali, is also the greatest achievement of Sudano-Sahelian architecture (Sudano-Sahelian refers to the Sudanian and Sahel grassland of West Africa). It is also the largest mud-built structure in the world. We experience its monumentality from afar as it dwarfs the city of Djenné. Imagine arriving at the towering mosque from the neighborhoods of low-rise adobe houses that comprise the city.

Djenné was founded between 800 and 1250 C.E., and it flourished as a great center of commerce, learning, and Islam, which had been practiced from the beginning of the 13th century. Soon thereafter, the Great Mosque became one of the most important buildings in town primarily because it became a political symbol for local residents and for colonial powers like the French who took control of Mali in 1892. Over the centuries, the Great Mosque has become the epicenter of the religious and cultural life of Mali, and the community of Djenné. It is also the site of a unique annual festival called the Crepissage de la Grand Mosquée (Plastering of the Great Mosque).

The Great Mosque that we see today is its third reconstruction, completed in 1907. According to legend, the original Great Mosque was probably erected in the 13th century, when King Koi Konboro—Djenné’s twenty-sixth ruler and its first Muslim sultan (king)—decided to use local materials and traditional design techniques to build a place of Muslim worship in town. King Konboro’s successors and the town’s rulers added two towers to the mosque and surrounded the main building with a wall. The mosque compound continued to expand over the centuries, and by the 16th century, popular accounts claimed half of Djenné’s population could fit in the mosque’s galleries.

The first Great Mosque and its reconstructions

Some of the earliest European writings on the first Great Mosque came from the French explorer René Caillié who wrote in detail about the structure in his travelogue Journal d’un voyage a Temboctou et à Jenné (Journal of a Voyage to Timbuktu and Djenné). Caillié traveled to Djenné in 1827, and he was the only European to see the monument before it fell into ruin. In his travelogue, he wrote that the building was already in bad repair from the lack of upkeep. In the Sahel—the transitional zone between the Sahara and the humid savannas to the south—adobe and mud buildings such as the Great Mosque require periodic and often annual re-plastering. If re-plastering does not occur, the exteriors of the structures melt in the rainy season. Based on Caillié’s description, his visit likely coincided with a period when the mosque had not been re-plastered for several years, and multiple rainy seasons had probably washed away all the plaster and worn the mud-brick.

A second mosque built between 1834 and 1836 replaced the original and damaged building described by Caillié. We can see evidence of this construction in drawings by the French journalist Felix Dubois. In 1896, three years after the French conquest of the city, Dubois published a plan of the mosque based on his survey of the ruins. The structure drawn by Dubois (above) was more compact than the one that is seen today. Based on the drawings, the second construction of the Great Mosque was more massive than the first and defined by its weightiness. It also featured a series of low minaret towers and equidistant pillar supports.

The present and third iteration of the Great Mosque was completed in 1907, and some scholars argue that the French constructed it during their period of occupation of the city starting in 1892. However, no colonial documents support this theory. New scholarship supports the idea that the mason’s guild of Djenné built the current mosque with the help of forced laborers from villages of adjacent regions, brought in by French colonial authorities. To accompany and motivate workers, musicians were provided who played drums and flutes. Workers included masons who mixed tons of mud, sand, rice-husks, and water and formed the bricks that shape the current structure.

The Great Mosque today

The Great Mosque that we see today is rectilinear in plan and is partly enclosed by an exterior wall. An earthen roof covers the building, which is supported by monumental pillars.

The roof has several holes covered by terra-cotta lids (above), which provide its interior spaces with fresh air even during the hottest days. The façade of the Great Mosque includes three minarets and a series of engaged columns that together create a rhythmic effect (below).

At the top of the pillars are conical extensions with ostrich eggs placed at the very top—symbol of fertility and purity in the Malian region. Timber beams throughout the exterior are both decorative and structural. These elements also function as scaffolding for the re-plastering of the mosque during the annual festival of the Crepissage. Compared to images and descriptions of the previous buildings, the present Great Mosque includes several innovations such as a special court reserved for women and a principal entrance with earthen pillars, that signal the graves of two local religious leaders.

Re-plastering the Mosque

During the annual festival of the Crepissage de la Grand Mosquée, the entire city contributes to the re-plastering of the mosque’s exterior by kneading into it a mud plaster made from a mixture of butter and fine clay from the alluvial soil of the nearby Niger and

Bani Rivers. The men of the community usually take up the task of mixing the construction material. As in the past, musicians entertain them during their labors, while women provide water for the mixture. Elders also contribute through their presence on site, by sitting on terrace walls and giving advice. Mixing work and play, young boys sing, run, and dash everywhere.

Over the years Djenné’s inhabitants have withstood repeated attempts to change the character of their exceptional mosque and the nature of the annual festival. For instance, some have tried to suppress the playing of music during the Crepissage, and foreign Muslim investors have also offered to rebuild the mosque in concrete and tile its current sand floor. Djenné’s community has unrelentingly striven to maintain its cultural heritage and the unique character of the Great Mosque. In 1988, the tenacious effort led to the designation of the site and the entire town of Djenné as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Backstory

The Great Mosque of Djenné is only one of many important monuments in the area known as the Djenné Circle, which also includes the archaeological sites of Djenné-Djeno, Hambarketolo, Tonomba and Kaniana. The region is known especially for its characteristic earthen architecture, which, as noted above, requires continuous upkeep by the local community.

Djenné’s unique form of architecture also makes it particularly susceptible to environmental threats, especially flooding. The town is situated along a river, and in 2016, torrential rains led to massive floods that caused one historic 16th-century palace to collapse, and left the Great Mosque with significant cracks its pillars. Construction of new buildings on the archaeological sites and inadequate waste disposal infrastructure also present continual problems.

UNESCO and other agencies have supported the restoration of the riverbanks in Djenné to help prevent flooding, and the four archaeological sites have now gained official status as properties of the state, which shields them from urban development. However, the conservation situation in Djenné remains fragile. Since the civil war in Northern Mali in 2012, the government has had limited bandwidth to deal with all of the various measures necessary to successfully protect, maintain, and monitor these sites. UNESCO has also noted a lack of funding from outside partners, who, according to the agency, have shown greater interest in Timbuktu, where terrorists vandalized several historic mausoleums and a mosque in 2012.

The current state of Djenné highlights the complex network of factors that affect world heritage: armed conflict and civil unrest, environmental threats, urban development, and lack of cooperation between agencies can all undermine the fate of monuments like the Great Mosque. Such circumstances remind us of the importance and the difficulty of conservation efforts not just in Djenné, but around the globe.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional Resources:

The website of the Great Mosque of Djenné

Katarina Höije, “The mud mosque of Mali” from Roads and Kingdoms (May 2018)

Old Towns of Djenné (from UNESCO)

UNESCO State of Conservation report for the Old Towns of Djenné

Dogon Couple (Dogon peoples)

by STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. PERI KLEMM

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Dogon Couple, 18th-early 19th century (Dogon peoples), Mali, wood and metal, 73 x 23.7 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Speakers: Dr. Peri Klemm and Dr. Steven Zucker

Is this a couple, or could this pair relate to a story from Dogon cosmology?

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Mask (Kanaga) (Dogon peoples)

Dogon masks, such as this one called kanaga, are worn primarily at dama, a collective funerary rite for Dogon men. The ritual’s goal is to ensure the safe passage of the spirits of the deceased to the world of the ancestors. The ceremony is organized by members of Awa, a male initiation society with ritual and political roles within Dogon society. As part of the public rites related to death and remembrance, Awa society members are responsible for the creation and performance of the masks.

Like other Dogon wooden masks, kanaga masks depict the face as a rectangular box with deeply hollowed channels for the eyes. The superstructure above the face identifies this mask as a kanaga: a double-barred cross with short vertical elements projecting from the ends of the horizontal bars. This abstract form has been interpreted on two levels: literally, as a representation of a bird, and, on a more esoteric level, as a symbol of the creative force of god and the arrangement of the universe. In the latter interpretation, the upper crossbar represents the sky and the lower one, the earth.

This kanaga mask was collected complete with some of its costume elements. Attached to the wooden face mask is a hood composed of plaited fiber strips dyed black and yellow with a short fiber fringe that covers the dancer’s head. A ruff of red and yellow fibers frames the face. The dancer also wore a black vest woven of fiber and embroidered with white cowry shells and fiber armbands at the wrists and elbows. This ensemble included a long skirt of loosely strung, curly black fibers and a short overskirt composed of straight red and yellow fibers, worn over trousers.

More than eighty different types of masks, of both wood and fiber, have been documented in dama performances. They represent various human characters familiar to the Dogon community, such as hunters, warriors, healers, women, and people from neighboring ethnic groups. The masks may also depict animals, birds, objects, and abstract concepts.

Because preparations are elaborate and costly, the dama may be held several years after the death and burial of an individual. Performances take place over a six-day period, culminating with a procession of masked dancers who escort the souls of the dead from the village, where they might cause harm, to their final resting place in the spiritual realm. The ceremony recalls the origins of the Dogon people, while also marking the end of the mourning period for the recently deceased. Today, such masks continue to be worn at dama performances but are also danced on other, more secular occasions, such as national holidays and as demonstrations organized for the benefit of tourists.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dogon art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dogon peoples from Art and Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Male and Female Antelope Headdresses (Ci wara) (Bamana peoples)

Pairs of carved wooden headdresses in the form of antelopes, like these examples, refer to the mythic culture hero Ci Wara, a divine force conceived of as half man and half antelope. Bamana oral traditions credit Ci Wara with introducing to humanity agricultural methods and an understanding of earth, animals, and plants. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Ci Wara was invoked and honored by members of a men’s agricultural association, also called ci wara, in village-wide performances that celebrated the skills of successful farmers. These performances featured a pair of dancers wearing sculpted headdresses, one representing a male antelope and the other a female. They held sticks in their hands to paw the earth just as the mythic Ci Wara did when he first taught men to plant seeds.

In performance, the paired dancers symbolize the union between men and women, essential for the continuity of the community. The formal features of the headdress also reference elements of nature necessary to sustain life. The male serves as a metaphor for the sun, while the female is associated with the earth. The long strands of raffia fibers attached to the headdress, concealing the dancer, are likened to streams of water.

Although ci wara headdresses are generally described as representing antelopes, they incorporate features of other animals, including aardvarks and pangolins. These animals are selected for their symbolic value. In this pair, the horns and long, arched neck represent the antelope, associated with grace and strength. The head with a long, pointed nose and the low-slung body are features of the aardvark, admired for its determination in digging. The sculpted headdress is attached to a basketry skullcap (now missing on these examples) and secured on top of the dancer’s head with a cotton strip. The dancer’s face would be covered by a semitransparent cloth, and a costume of darkened raffia fiber would cloak the dancer’s body.

The silhouette-like nature of sculptural representation is noted for its elegant play of positive and negative space. The male, identified as a roan antelope, is distinguished by its long horns and elaborate openwork mane. The female, representing an oryx antelope, carries a fawn on her back, a reference to human mothers, who carry babies on their backs as they till the fields. The face and horns of both are decorated with delicate chip-carved patterning, incised linear designs, and metal appliqué and strips.

The Bamana, who live in the southern part of present-day Mali, have long considered farming to be among the most noble of all professions. Traditionally, Bamana farmers have worked arduously in the savanna fields from May to October, when it rains regularly, in order to provide enough food during the long, dry season. Today, despite the significant social changes that have impacted contemporary Bamana experience, farming remains central to their identity. Although many Bamana have adopted Islam over the course of the last century, theatrical ci wara dances continue in many Bamana villages, celebrating their agrarian lifestyle. Among the continent’s most well-known forms of expression, the elegantly abstract form of the ci wara headdress has also been adopted as a national symbol of cultural identity, used as a logo by Mali’s official airline and found on the national currency.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): The Artist Project: Willie Cole (from The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Willie Cole, born in 1955, is an American sculptor who lives and works in New Jersey. See an example of his work here.

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bamana art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ci Wara on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Bamana peoples on Art and Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Genesis: Ideas of Origin in African Sculpture (Met publication)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Kòmò Helmet Mask (Kòmòkunw) (Bamana peoples)

This headdress (above) was made and used by a member of the Komo society, an association of blacksmiths found among the Bamana and other Mande-speaking communities in the region. Komo association members enforce community laws, make judicial decisions, and offer protection from illness, misfortune, and malevolent forces. The headdress embodies the secret knowledge and awesome power of the society; its rough and unattractive form is therefore intended to be visually intimidating. While works like the Bamana maternity figure (left) depict a human ideal, this headdress is explicitly about harnessing the forces of untamed nature, a concept expressed visually in its form and material.

The wooden structure of the headdress has a domed head, gaping mouth, and long horns. Attached are antelope horns, a bird skull with a sharp beak, and porcupine quills, elements chosen for their metaphorical associations since they provide animals with power and protection. The animals themselves hold symbolic value in Bamana culture. Birds, for example, are associated with wisdom and divinatory powers, while porcupines signify the importance of preserving knowledge. The mask was further enhanced by the application of ritual substances formed from a mixture of earth, sacrificial animal blood, and medicinal plants. This material was replenished on a regular basis, endowing the mask with the critical life force, or nyama, that is the source of its extraordinary power.

Komo society headdresses are made by blacksmiths, a specialized artisan group among the Bamana whose profession is inherited. Blacksmiths are greatly respected within their community for the special knowledge and technical skills that allow them to use fire, water, and air to transform iron ore into tools and weapons. Ironworking is considered an especially dangerous profession, one that requires courage and extraordinary abilities to manage the potentially destructive spiritual forces released during the process. Blacksmiths are therefore uniquely qualified to create Komo headdresses, which combine terrifying forms and inherently harmful materials in an object of benefit to the community.

The headdress is worn in dramatic performances that serve as a focal point of Komo society meetings. Held in private and restricted to initiated members, these meetings provide an opportunity to gain an understanding of the society’s history, beliefs, and rituals. Accompanied by bards and musicians, a high-ranking Komo member appears wearing a headdress like this strapped on the top of his head. His face is covered with a semitransparent cloth and he wears a costume of black feathers enhanced with amulets over a hooped skirt. The dancer’s performance is acrobatic and intense, featuring spectacular feats that suggest extraordinary powers. His performance responds to petitions for assistance from members of the community. Through song and dance, the Komo member gradually reveals solutions to a variety of concerns that have been presented to him, from crop failure to infertility.

Considered the most powerful of men’s associations in the region, Komo has an ancient history and was well established by the time the Mali empire rose to power in the thirteenth century. Individual community branches of Komo, which are distributed widely across the region, gain authority through strong leadership, coalitions with wilderness spirits, and effective use of power objects.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Seydou Keïta, Untitled (Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress)

![Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997, Mali, Bamako, gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/hb_1997-364.jpg)

Commercial studio portrait photography was introduced in Mali in the 1930s and developed into a thriving industry in Bamako, the capital city, during the postwar period. Bamako’s rapid economic development and accompanying population boom fueled demand for photographic portraits. Such photographs were commissioned by members of the growing middle class as mementos to be displayed on the walls of their homes or sent to faraway family members.

Among the busiest portrait studios in Bamako was that of photographer Seydou Keïta. Born in 1923, Keïta originally apprenticed as a carpenter but found his vocational calling when he was given a 6 x 9 Kodak Brownie camera by his uncle. After experimenting on his own, Keïta learned darkroom techniques from two established commercial photographers. He opened his own studio in 1948 in Bamako-Koura, an area of the city whose proximity to a train station and popular marketplace ensured a steady stream of potential clients.

Keïta soon became highly successful as a commercial photographer, producing tens of thousands of portraits over the course of his career. He developed a consistent and recognizable signature style that proved popular with local clients, who requested that their prints include a stamp with Keïta’s name. A typical sitting took place during the day in his outside courtyard and could last up to an hour. Keïta gave his sitters the opportunity to individualize their portraits, helping them select a flattering pose and offering a variety of accessories as props. He posed his clients against a printed cloth, which often resulted in vibrant juxtapositions between the patterns of the sitter’s clothes and that of the backdrop. Other compositional strategies included the use of a shallow depth of field and an emphasis on repetition and symmetry in framing his subject.

In this portrait, a woman reclines on her side with a relaxed and self-possessed dignity. The tight cropping places the focus entirely on the sitter, while the camera angle makes her appear on a slightly tilted slope, creating a symmetrical composition. The floral print of the woman’s boubou (a traditional form of dress) contrasts with the bold black and white checkered blanket in the foreground and the swirling arabesques of the cloth backdrop, creating a syncopated clash of patterns and rhythms. Her dress and pose communicate significant aspects of her identity, revealing how traditional concepts of portraiture are maintained and modified through the medium of photography. Her head wrap is worn in a trendy style called “à la Gaulle,” its jaunty angle framing the scarification marks of ethnic affiliation that she bears on her forehead. She rests her left arm casually at her waist, dangling her long slender fingers, which are considered a sign of high social standing.

When Mali won independence from France in 1962, Keïta was offered a position as official government photographer, where he remained until 1977. His governmental responsibilities required him to close his studio in 1964 and he never reopened his portrait practice, although he did continue his photography. Beginning in the 1990s, Keïta’s work was included in several exhibitions in the United States and Europe, bringing him considerable fame in the international art world.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

The art of Nigeria

From the Kingdom of Benin to the arts of the Yoruba, Nigeria is home to ancient and vibrant art traditions.

c. 15th century - present

Benin Plaques

by DR. KATHRYN WYSOCKI GUNSCH and DR. BETH HARRIS

How to impress your courtiers: a lesson from the Kingdom of Benin

Additional resources

Benin plaques at the MFA, Boston

Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch, The Benin Plaques A 16th Century Imperial Monument, Oxford: Routledge, 2018

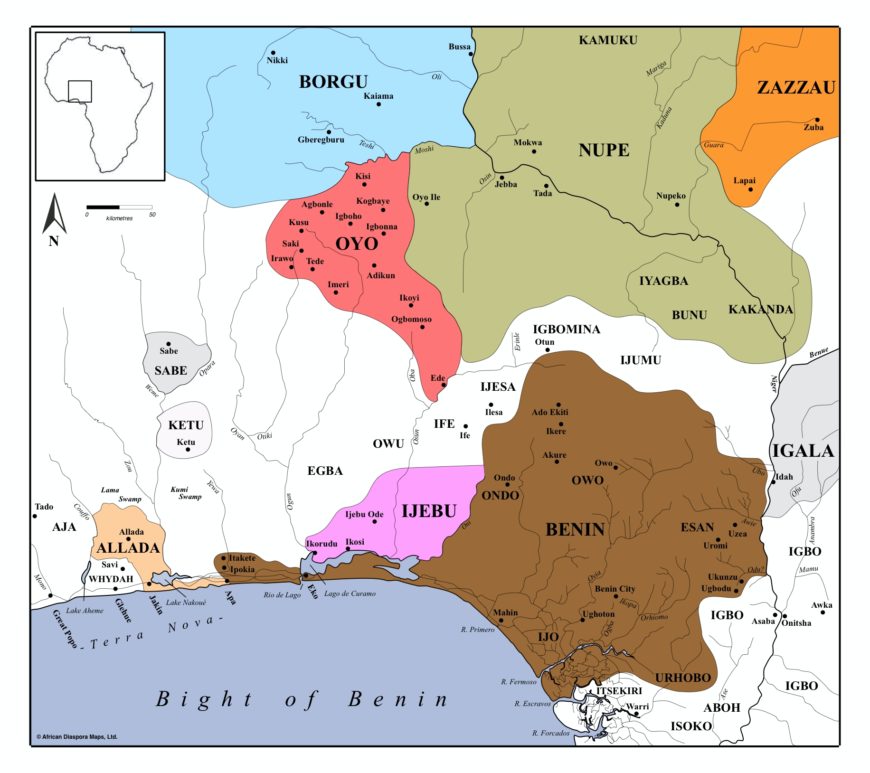

The Kingdom of Benin

Until the late 19th century, one of the major powers in West Africa was the kingdom of Benin, in what is now southwest Nigeria. When European merchant ships began to visit West Africa from the 15th century onwards, Benin came to control the trade between the inland peoples and the Europeans on the coast. The kingdom of Benin was also well known to European traders and merchants during the 16th and 17th centuries, when it became wealthy partly due to the slave trade.

A vivid picture

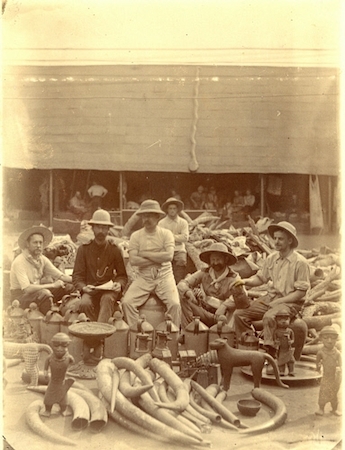

When the British tried to expand their own trade in the 19th century, the Benin people killed their envoys. So in 1897, the British sent an armed expedition which captured the king of Benin, destroyed his palace and took away large quantities of sculpture and regalia, including works in wood, ivory and especially brass. Some of these objects came from royal altars for the king’s ancestors, but among them were a large number of cast brass plaques made to decorate the wooden pillars of the palace. These had been left in the palace storerooms while part of the palace was being rebuilt. As it later emerged, most of them were probably made between about 1550 – 1650. The people and scenes that the plaques depict are so many and varied that they give a vivid picture of the court and kingdom of that time. The plaques were most sought after and were bought by museums across Europe and America—you can see them at the British Museum, in Chicago, Vienna, Paris and a large collection can be viewed in Berlin.

A sensation

The arrival and reception of the bronze plaques caused a sensation in Europe. Scholars struggled to understand how African craftsmen could have made such works of art, proposing some wild theories to explain them. Quickly, however, research showed that the Benin bronzes were entirely West African creations without European influence, and they transformed European understanding of African history.

The plaques

When the son of the deposed king revived the Benin monarchy in 1914, now under British rule, he did his best to restore the palace and continue the ancient traditions of the Benin monarchy. Because these traditions are followed in the modern city of Benin, it is still possible to recognize many of the scenes cast in brass by Benin artists about five hundred years ago.

As decorations for the halls of the king’s palace, the plaques were designed to proclaim and glorify the prestige, status, and achievements of the king, so they give an informative but very one-sided view of the kingdom of Benin. They do not show how the ordinary people lived in the villages outside the city as farmers, growing their yams and vegetables in gardens cleared from the tropical forest. Nor do they show how most of the townspeople lived, employed in crafts such as the making of the brass plaques themselves. And most striking of all, there are no women or children shown in the plaques, which means that more than half of the people of the king’s court are not shown.

Many of the brass plaques from the king’s palace show images of Portuguese men, whose costumes indicate that they were made during the 16th and 17th centuries. Although Benin had no gold to offer, they supplied the Portuguese with pepper, ivory, leopard skins and people, who were taken as slaves to work elsewhere in Africa and in the Portuguese colonies in Brazil. Many of these people were captives taken in the wars in which the Benin people conquered their neighbours far and wide and made them part of the kingdom, or they were sent by the conquered local chiefs as tribute to the king.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Benin Art: Patrons, Artists and Current Controversies

In the age of social media, nearly everyone can present an idealized version of their real lives to the world. In the past, however, only the wealthiest and most powerful could afford to shape their image for the public. During the sixteenth century, the kings of Benin (in present-day Nigeria), reigned over nearly two million subjects and commanded a feared military force, but they also faced internal political problems that threatened the throne.

Politics, power, and art

The Kingdom of Benin was founded around the year 900, but it reached the height of its power in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as a result of the conquests of new territories by two kings —Oba Ewuare and his son Oba Ozolua (Oba means “king”).

The Obas of Benin amassed great wealth by controlling trade routes reaching from the river Niger in the East to the western border with the kingdom of Dahomey. Taxes on pepper, ivory, and enslaved persons, and annual tribute payments from conquered lands in their expanding empire, also increased the wealth of the Kingdom.

Royal art from this period (and from a slightly later time of renewed wealth and power in the eighteenth century), was designed to broadcast and strengthen dynastic power. Benin court art celebrates the prestige of the monarchy to outsiders (like traders and ambassadors), as well as to courtiers who might try to wrest power from the king.

In the early sixteenth century, Oba Esigie successfully consolidated Benin’s power over conquered territories. He took the throne after a civil war with his older brother and soon after defended Benin City from an attack from a neighboring kingdom (Idah). His commissions were designed to address the turmoil of his early reign. Esigie was a brilliant politician, and he commissioned great works of art and new festivals to assert the legitimacy of his reign.

The festival of Ugie Oro

Esigie instituted the festival of Ugie Oro, where high-ranking courtiers process around Benin City striking bronze staffs with a bird on top. The festival refers to the Idah war, when leading courtiers refused to support Esigie in his defense of the city. A bird in a tree en route to the battle prophesied that Esigie and his troops would be defeated. Esigie shot the bird and carried it as his battle standard. When he won the war against the Idah, he instituted the festival to point out that the advice of the courtiers—and the bird—had been nothing more than the empty noise produced by clanging the bronze staffs, pointing out that courtiers’ should defer to the wisdom of the king.

In the plaques he commissioned to ornament his audience hall, Esigie surrounded himself with images of courtiers in processions, including the festival of Ugie Oro, or engaging in other acts of service and praise—reminding them to honor and obey his authority. Today, artworks from the period of Esigie’s reign are among the most celebrated in African art history, combining fascinating narratives on the majesty of the kingdom, luxurious materials, and fine workmanship.

Royal Patronage in the 18th and 19th centuries

Changes in Benin art are tightly intertwined with the changing fortunes of the kingdom, because the Oba was historically the primary patron for all artwork in bronze and ivory. In the beginning of the eighteenth century, Benin recovered from a series of succession struggles and wars that weakened the court and devastated its finances. Oba Akenzua I and his successor, Oba Eresoyen, strengthened the king’s role and instituted new traditions and art forms to signal their regained power.

Akenzua and Eresoyen ushered in a period of renewed wealth and political power for the kingdom that continued into the 19th century. Akenzua and Eresoyen compared themselves to Ozolua and Esigie, starting the tradition of viewing Ozolua and Esigie as two of the most important kings in Benin history.

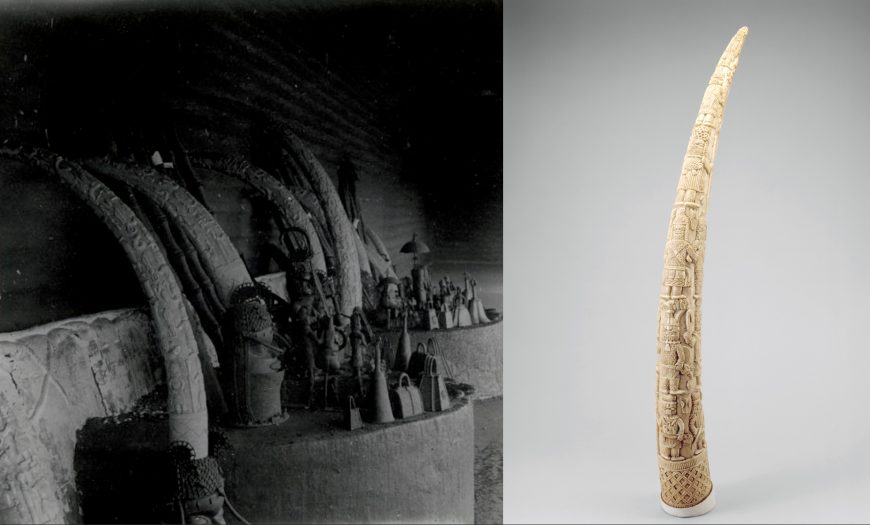

Oba Eresoyen was a major patron of the bronze-casting guild, and commissioned an elaborate copy of a bronze state stool owned by Oba Esigie—metaphorically connecting the two reigns. Eresoyen is also known as a patron of the ivory guild, and may have introduced the intricately carved tusk for memorial altars that first appear in the eighteenth century.

On memorial altars, ten to sixty tusks were displayed on top of brass commemorative heads. The tusk held in the Berlin Ethnographic Museum, is one of the oldest known. We see an Oba, his arms supported by attendants, placed in the center of the tusk, the most visible position. Surrounding this central triad are figures relating to the dynasty of great Obas—including two Portuguese men on horseback that refer to the reigns of Ozolua and Esigie—and motifs representing leading courtiers and priests serving the king.

The Artists

The Igun Eronmwon (brass-caster’s guild), and the Igbesanmwan (ivory and wood carvers’ guild), are responsible for all the art made for the Oba. Until the 20th century, royal artists were not allowed to make pieces for other clients without special permission. Membership in the royal artists’ guilds is hereditary—even today. The head of each guild inherits his position from his father. He is responsible for receiving commissions from the king, overseeing the design of the work, and assigning parts of the project to different artists. For this reason, nearly all historical Benin art is made in a workshop style, with individual artists contributing pieces of the whole.

While the Igun Eronmwon and Igbesanmwan guilds are separate, they often make artworks that are displayed together. Commemorative heads made for the memorial altar of a king (see ancestral altars above), for example, combine a cast-bronze head with a carved ivory tusk rising from the top, just as an ivory leopard may be finished with inlaid bronze spots.

Controversy

Like other artworks taken from their place of origin by colonial occupiers, artworks from Benin are part of a public conversation on cultural patrimony and the ethics of collecting. The provenance (ownership history), of Benin artworks in Europe and America usually includes a moment in 1897 when Benin City was invaded by British soldiers and a part of the royal treasury was claimed by the British state as spoils of war. In the following years, other artworks were taken from Benin by individual soldiers, or pillaged from the palace and sold.