4.4: East Africa and the Horn of Africa

- Last updated

- Apr 30, 2022

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147760

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

East Africa

For two millennia, East Africa has been home to powerful empires and prosperous trading cities.

c. 1 C.E. - present

About East Africa

by SMARTHISTORY

East Africa is made up Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Djibouti (Horn of Africa), Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi (the African Great Lakes region) and the island nations of Comoros, Mauritius, Seychelles, Réunion and Mayotte in the Indian Ocean.

The art of Ethiopia

Ethiopia is known for its magnificent churches, illuminated manuscripts, and world-famous contemporary art.

c. 1 C.E. - present

Christian Ethiopian art

Ethiopia is a country in Africa with ancient Christian roots. It possesses a vigorous artistic tradition and is home to hundreds of old churches and monasteries perched at the top of hard-to-access mountains, hidden by lush vegetation, or surrounded by the tranquil waters of one of its lakes.

What is Christian Ethiopian art?

The introduction of Christian elements in art and the construction of churches in Ethiopia must have started shortly after the introduction of Christianity and continues to this day, since about half of the population are practicing Christians. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church claims that Christianity reached the country in the 1st century C.E. (thanks to the conversion of the Ethiopian eunuch described in the Acts of the Apostles 8:26-38), while archaeological evidence suggests that Christianity spread after the conversion of the Ethiopian king Ezana during the first half of the 4th century C.E.

The term “Christian Ethiopian art” therefore refers to a body of material evidence produced over a long period of time. It is a broad definition of spaces and artworks with an Orthodox Christian character that encompasses churches and their decorations as well as illuminated manuscripts and a range of objects (crosses, chalices, patens, icons, etc.) which were used for the liturgy (public worship), for learning, or which simply expressed the religious beliefs of their owners. We can infer that from the thirteenth century onwards works of art were for the most part produced by members of the Ethiopian clergy.

Periodization

Artworks from Ethiopia can and should be contextualized within the country’s historical development. Scholars still disagree on how to divide and classify the development of Christian Ethiopian art into chronological phases. In this essay, the development of Christian Ethiopian art is broadly divided into the eight periods listed below, but it must be kept in mind that the dates for the earlier periods are still debated and we have very limited evidence prior to the early Solomonic period (1270-1527).

The Christian Aksumite Period (c. 4th-8th centuries C.E.)

This period takes its name from the city of Aksum which had been the capital of Ethiopia for several centuries before the conversion to Christianity of King Ezana (who ruled from c. 320–360) and served as capital for several centuries after. While we cannot rule out the possibility that Christianity had been present in the country prior to the conversion of this ruler, it is only starting from this period that expressions of distinctly Christian beliefs appear in the material record.

A small number of Ethiopian churches, such as Debre Damo (above) and Degum, can be tentatively ascribed to the Aksumite period. These two structures probably date to the 6th century or later. Still standing pre-6th century Aksumite churches have not been confidently identified. However, archaeologists believe that a small number of now-ruined structures dating to the 4th or 5th century functioned as churches—a conclusion based on features such as their orientation. A large stepped podium in the compound of the church of Mary of Zion in Aksum (considered by the Ethiopians as the dwelling place of the Ark of the Covenant), probably once gave access to a large church built during this period.

Aksumite churches adopted the basilica plan. These churches were constructed using well-established local building techniques and their style reflects local traditions. Although very little art survives from the Aksumite period, recent radiocarbon analyses of two illuminated Ethiopic manuscripts known as the Garima Gospels suggest that these were produced respectively between the 4th-6th and 5th-7th centuries. Aksumite coins (left) can also be looked at to gain insight into artistic conventions of the period.

The Post-Askumite period (c. 8th/9th-12th centuries C.E.)

A number of factors contributed to the gradual impoverishment and decline of the Aksumite kingdom. The Arab expansion into Northern Africa cut off the kingdom’s access to the Red-Sea waterway (and to the markets which could be reached through it and on which a large part of the kingdom’s prosperity had been based). There is also evidence to suggest that some of the kingdom’s natural resources, such as gold and ivory, had been depleted. Very little is known about this phase of Ethiopian history and scholars even disagree on the dates of its beginning and end.

The political center of Ethiopia seems to have gradually shifted to the southern and eastern parts of the Tigray region in the Post-Aksumite period. A few churches in these areas have been tentatively attributed to this period, but subsequent adaptations combined with the inability to obtain permissions to conduct archaeological surveys make dating difficult. It seems likely that churches continued to be built as well as hewn (cut) out of rock. A group of funerary hypogea (underground chambers) in the Hawzien plain (in northern Ethiopia) may have been transformed into churches during the post-Aksumite period. This could be the case for churches such as Abreha-we-Atsbeha (below) and Tcherqos Wukro (the paintings in these churches probably date from a later period). According to local oral traditions, a small number of iron crosses date to the Aksumite or Post-Aksumite periods, but the absence of reliable dating methods and the fact that such crosses were produced at least until the sixteenth century, makes it extremely difficult to verify these claims.

The Zagwe period (c. 1140-1270 C.E.)

By the first half of the twelfth century, the center of power of the Christian Kingdom had shifted even further south, to the Lasta region (a historic district in north-central Ethiopia). From their capital Adeffa, members of the Zagwe dynasty (from whom this period takes its name), ruled over a realm which stretched from much of modern Eritrea to northern and central Ethiopia. While limited evidence about their capital exists, the churches of Lalibela—a town which takes its name from the Zagwe ruler credited with its founding—stand as a testament to the artistic achievements of this period.

Lalibela includes twelve buildings destined for worship which, together with a network of linking corridors and chambers, are entirely carved or “hewn” out of living rock. The tradition of hewing churches out of rock, already attested in the previous periods, is here taken to a whole new level. The churches, several of which are free-standing, such as Bete Gyorgis (Church of St. George, image at top of page), have more elaborate and well-defined façades. They include architectural elements inspired by buildings from the Aksumite Period. Furthermore, some, such as Bete Maryam, feature exquisite internal decorations (above), which are also carved out of the rock, as well as wall paintings. The interiors of the churches blend Aksumite elements with more recent elements of Copto-Arabic derivation. In Bete Maryam, for example, the architectural elements—such as the hewn capitals and window frames—imitate Aksumite models (see below), whereas the paintings can be compared with those in the medieval Monastery of St. Antony at the Red Sea.

Several wooden altars survive from this period, some decorated with figures, together with numerous crosses, some of which are engraved. No illuminated manuscripts or icons from this period have been discovered thus far.

The Early Solomonic period (1270-1527)

By 1270, the last Zagwe ruler was overthrown by Yekunno Amlak, who claimed to descend from the kings of the Aksumite period and traced his lineage all the way back to the biblical union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. His descendants—the Solomonics—ruled Ethiopia until the third quarter of the twentieth century. For much of this period, the Solomonics did not have a fixed capital, but moved across the country according to the seasons and their needs.

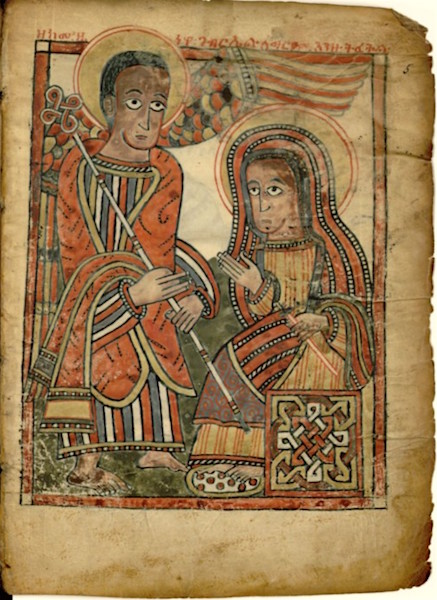

The Solomonics were as active as patrons of the arts as their predecessors, and endowed churches with hundreds of precious gifts. Works of art were also donated to ecclesiastic centers by nobles and clergymen, as well as by individuals known from dedicatory inscriptions on the work they commissioned. The rock-cut church of Gannata Maryam, a few kilometers south-east of Lalibela, features an almost complete set of murals depicting saints, angels, and motifs inspired by the New Testament. The church also features a portrait of Yekunno Amlak. Numerous illuminated manuscripts, particularly Gospel books, were created between the late thirteenth and early fifteenth centuries. A few dozen feature not just Canon Tables and portraits of the four Evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John), as in the earlier Garima Gospels, but also scenes from the Old and New Testaments.

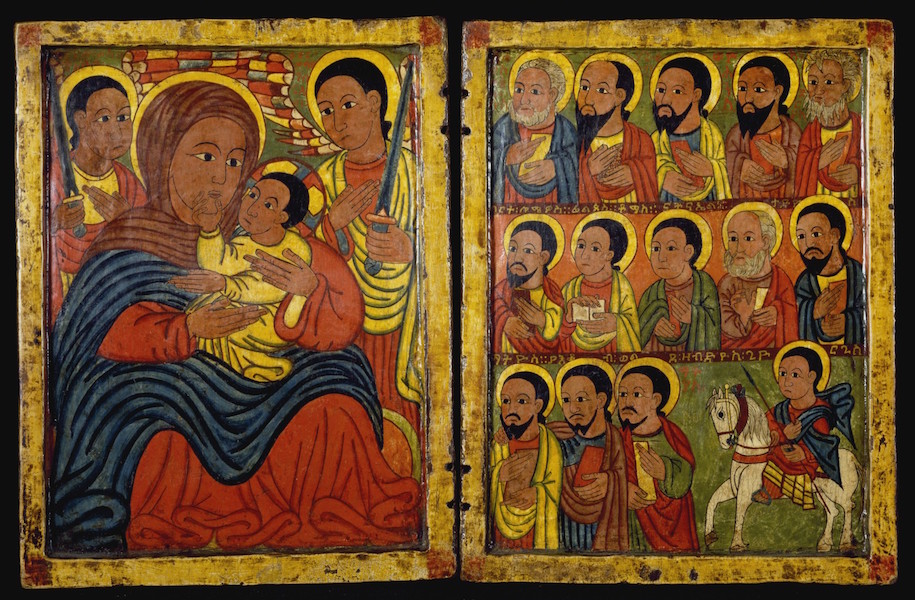

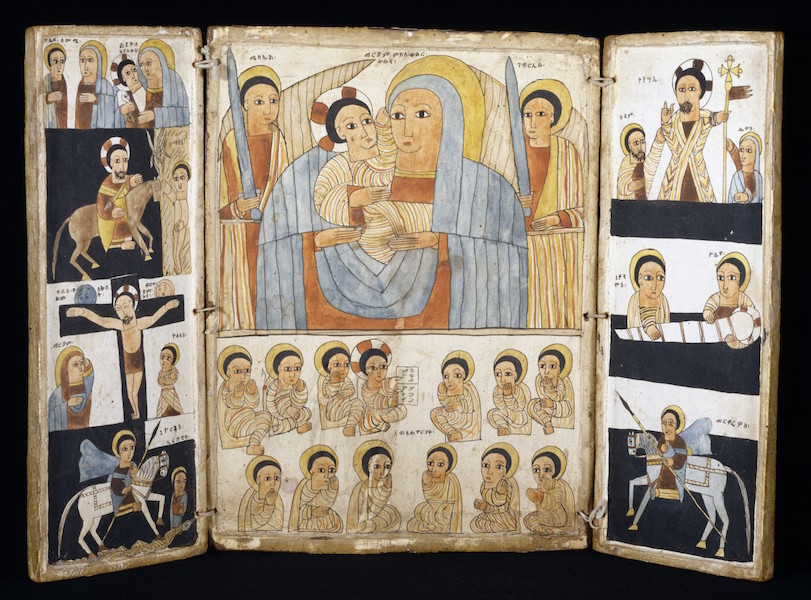

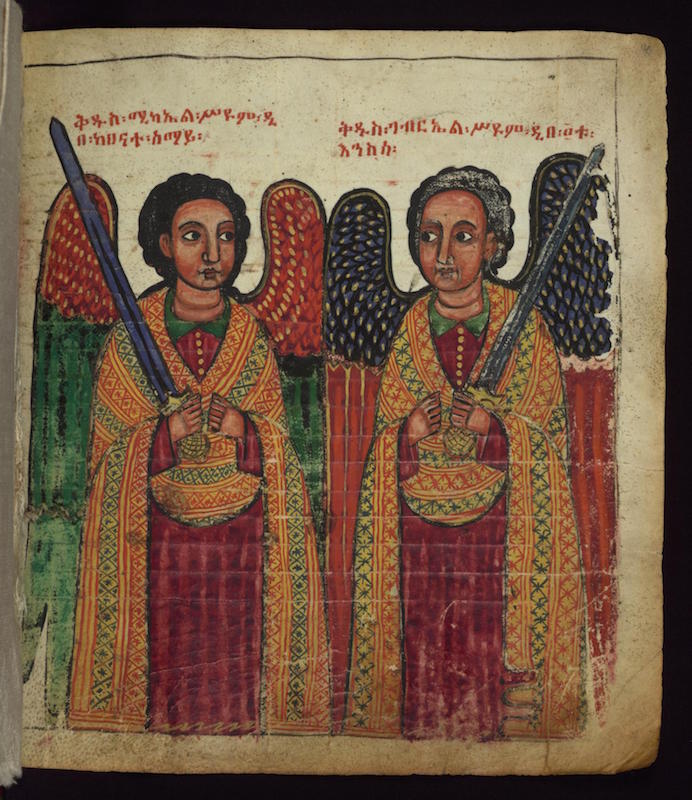

By the turn of the fifteenth century other manuscripts, especially Psalters, are frequently illustrated and crosses are often embellished with depictions of saints and of the Virgin and Child (above). The earliest surviving Ethiopian icons also date from this century (above and below). Written sources suggest that the Ethiopian Emperor Zar’a Ya’eqob encouraged the use of panel paintings in church rituals. While other artistic mediums used during the fifteenth century are largely indebted to the art of the fourteenth century, the icons feature new iconographic motifs and the lines are more elegant and sinuous and the figures have less rigid poses.

The mid-Solomonic period (1527-1632)

After a period of relative stability in the fifteenth century, a sequence of events shook the Ethiopian kingdom to its foundations, bringing it to the brink of collapse. First, came an invasion from the neighboring Muslim Sultanate of Adal led by a general called Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi whose army pillaged and destroyed numerous churches and Christian works of art across the country between 1529 and 1543. Incursions by the Oromo people from the south throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries further strained the country’s fragile structures. To make matters worse, the conversion to Catholicism of Emperor Susenyos in 1622 soon plunged the country into a civil war, for many of his subjects refused to adhere to the religious beliefs and liturgical practices that the Jesuit missionaries present in Ethiopia wanted to enforce. The conflict lasted until his abdication in favor of his son Fasilides in 1632.

This phase of Ethiopian art has been sometimes described as period of “transition” because artworks produced during the sixteenth century still include stylistic and iconographic elements that are typical of the fifteenth century, while foreshadowing developments which will take place in the second half of the seventeenth century. However, as such, this description of transition is applicable to most historical periods, and is therefore not particularly helpful. The art produced during the mid-Solomonic period reflects the difficult situation the country was in. The practice of decorating manuscripts with pictures and geometric motifs declined considerably, and few crosses and churches have been confidently attributed to the sixteenth century. Moreover, although numerous icons from this period have survived, these seldom achieve the linear elegance of painted panels from the fifteenth-century.

The Gondarine period (1632-1769)

The ascent to the throne of Fasilides in 1632 marks the beginning of a period of renewed stability for Ethiopia and the Solomonic dynasty. Fasilides ordered a new a capital, Gondar, about 50 kilometers north of Lake Tana (the largest lake in Ethiopia). He and his successors funded the construction of palaces and banquet halls within the royal compound that still exist today and they promoted the building of churches near by and in the Lake Tana region. The adoption of a circular plan for the construction of churches becomes standard (as opposed to the longitudinal format of the basilica).

Scholars usually divide the Gondarine period into two stylistic phases. The first Gondarine style (above), is characterized by the use of bright colors and the absence of shading. The clothing, often embellished with decorative elements, is usually painted in red, blue or yellow and the folds are indicating with simple parallel lines. The contour lines are well-defined and the modeling of the face is executed using a plain coral red resulting in an unnatural effect.

Works painted in the second Gondarine style (below), which was developed roughly during the reign of Iyasu II (1730-1755), have darker shades of color; the contour lines become lighter and a more delicate use of shading confers volume to the bodies and faces of the figures. A number of new themes, many of which were inspired from books printed in Europe, appear during the eighteenth century and it becomes increasingly common to find depictions of donors and patrons. Numerous crosses (like this processional cross from The British Museum), decorated with depictions of the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and saints were produced during the second part of the Gondarine period.

Zemene Mesafint period (1769-1855)

The period known as Zemene Mesafint, or the Era of Judges, begins with the deposition of Emperor Iyosas. This period, which lasted almost a century, saw a decline in the prestige, influence, and authority of the Solomonics, and witnessed the rise of a number of regional warlords who fought against each other for supremacy. This period has received less attention from historians, but seems to have been characterized by a decline in the production of art. Paintings from this period are strongly indebted to works executed during the second Gondarine style in terms of themes and forms, but the palette used by artists moves once again toward bright, plain colors.

The Late Solomonic period (1855-1974)

The final historical period begins with the ascent to the throne of Tewodros II, who claimed Solomonic descent and ends with the deposition of Haile Selassie, the event that marks the end of Solomonic rule in Ethiopia.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, church painting continues to show indebtedness to the second Gondarine style, but contemporary figures and events are depicted next to religious subjects with an increasing frequency. Moreover, while patrons had occasionally been depicted from the Zagwe period onwards in an idealized manner, by the turn of the twentieth century they are portrayed more realistically, as can be seen by the painting of Emperor Menelik II (above) in the church of Entoto Raguel. After the Second World War, traditionally trained Ethiopian painters, such as Qes Adamu Tesfaw, continued to work alongside artists influenced by modernism. The use of imported synthetic colors became increasingly common and by the 1960s icons and manuscripts were created, to a large extent, for the tourist market.

Additional resources

Biblical narrative of the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon (I Kings 10)

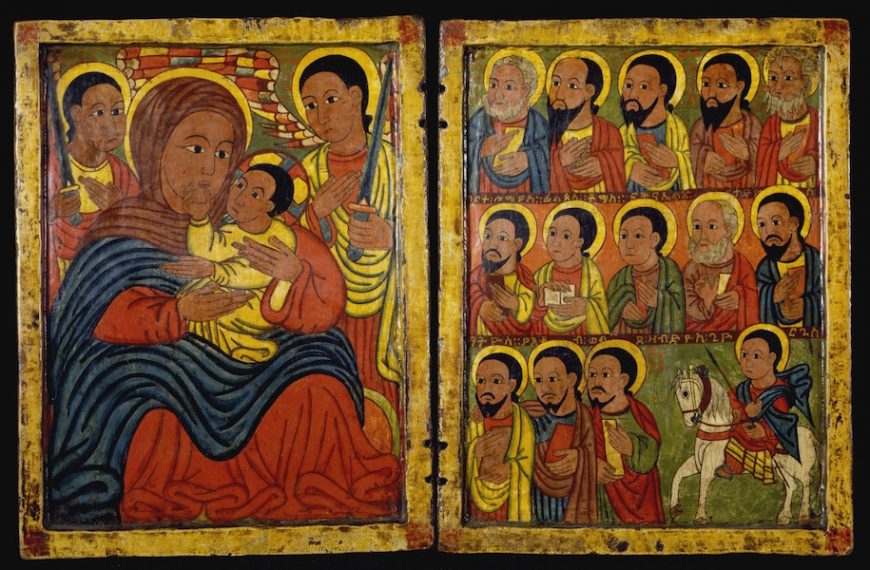

An Ethiopian icon

The term icon is used to refer to a devotional image. It is typically painted on a flat wooden panel, although in Ethiopia, as in other traditions, materials such as metal or stone could also be used to produce this type of image. The earliest known Ethiopian icons have been dated to the fifteenth century and are generally painted with tempera on gesso-primed wooden panels. Ethiopian icons from this period typically portray the Virgin and Child, the Apostles, and Saint George.

The piece shown here, which can be dated tentatively to the second half of the fifteenth century, features precisely such a combination of subjects. On the left panel, the Child touches his Mother’s chin, a gesture of tenderness which appears more frequently in works from this period onwards. The central pair is flanked by two angels with unsheathed swords who act as their royal guard.

The right panel is decorated with portraits of the Apostles who turn their gaze in adoration towards the Virgin and Child. In the bottom right corner is a representation of Saint George on horseback. The names of several of the figures on the right panel have been written on the borders which divide the scene into registers. It is likely that inscriptions identifying the upper row of Apostles and the Virgin and Child were originally present on the upper frame of the two panels. Icons such as this were most likely created to encourage devotion towards the Virgin Mary in accordance with the wishes of the Ethiopian emperor Zarʾa Yaʿ ǝqob (who ruled from 1434–68) and would have been used in churches and in religious processions.

Additional resources:

Jacopo Gnisci, “A Fifteenth-Century Ethiopian Icon of the Virgin and Child by the Master of the Amber-Spotted Tunic,” Rassegna di Studi Etiopici, vol. 65 (2019), pp. 183–93.

Marilyn E. Heldman, The Marian Icons of the Painter Frē Ṣeyon: A Study in Fifteenth-Century Ethiopian Art, Patronage, and Spirituality (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1994).

The kingdom of Aksum

One of the four greatest powers in the world

Aksum was the name of a city and a kingdom which is essentially modern-day northern Ethiopia (Tigray province) and Eritrea. Research shows that Aksum was a major naval and trading power from the 1st to the 7th centuries C.E. As a civilization it had a profound impact upon the people of Egypt, southern Arabia, Europe and Asia, all of whom were visitors to its shores, and in some cases were residents.

Aksum developed a civilization and empire whose influence, at its height in the 4th and 5th centuries C.E., extended throughout the regions lying south of the Roman Empire, from the fringes of the Sahara in the west, across the Red Sea to the inner Arabian desert in the east. The Aksumites developed Africa’s only indigenous written script, Ge’ez. They traded with Egypt, the eastern Mediterranean, and Arabia.

Despite its power and reputation—it was described by a Persian writer as one of the four greatest powers in the world at the time—very little is known about Aksum. Written scripts existed, but no histories or descriptions have been found to make this African civilization come alive.

A counterpoint to the Greek and Roman worlds

Aksum provides a counterpoint to the Greek and Roman worlds, and is an interesting example of a sub-Saharan civilization flourishing towards the end of the period of the great Mediterranean empires. It provides a link between the trading systems of the Mediterranean and the Asiatic world, and shows the extent of international commerce at that time. It holds the fascination of being a “lost” civilization, yet one that was African, Christian, with its own script, coinage, and international reputation. It was arguably as advanced as the Western European societies of the time.

The society was hierarchical with a king at the top, then nobles, and the general population below. This hierarchy can be discerned by the buildings that have been found, and the wealth of the goods found in them. Although Aksum had writing, very little has been found out about society from inscriptions. It can be assumed that priests were important, and probably traders, too, because of the money they would have made. Most of the poor were probably craftsmen or farmers. In some descriptions, the ruler is described as “King of Kings” which might suggest that there were other, junior kings in outlying parts of the empire which the Aksumites gradually took over.There is evidence of at least 10–12 small towns in the kingdom, which suggests it was an urban society, but for descriptions of these there is only archaeological evidence. Little or nothing is known about such things as the role of women and family life.

Christianity

Aksum embraced the Orthodox tradition of Christianity in the 4th century (c. 340–356 C.E.) under the rule of King Ezana. The king had been converted by Frumentius, a former Syrian captive who was made Bishop of Aksum. On his return, Frumentius had promptly baptized King Ezana, who then declared Aksum a Christian state, followed by the king’s active converting of the Aksumites. By the 6th century, King Kaleb was recognized as a Christian by the emperor Justin I of Byzantium (ruled 518–527) when he sought Kaleb’s support in avenging atrocities suffered by fellow Christians in South Arabia. This invasion saw the inclusion of the region into the Aksumite kingdom for the next seven decades.

Judaism

Although Christianity had a profound effect upon Aksum, Judaism also had a substantial impact on the kingdom. A group of people from the region called the Beta Israel have been described as “Black Jews.” Although their scriptures and prayers are in Ge’ez, rather than in Hebrew, they adhere to religious beliefs and practices set out in the Pentateuch (Torah), the religious texts of the Jewish religion. Although often regarded by scholars/academics as not technically ‘”Jewish” but instead a pre-Christian, Semitic people, their religion shares a common ancestry with modern Judaism. Between 1985 and 1991 almost the whole Beta Israel population of Ethiopia was moved to Israel.

Solomon and Sheba

The Queen of Sheba and King Solomon are important figures in Ethiopian heritage. Traditional accounts describe their meeting when Sheba, Queen of Aksum, went to Jerusalem, and their son Menelik I formed the Solomonic dynasty from which the rulers of Ethiopia (up to the 1970s) are said to be descended. It has also been claimed that Aksum is the home of the Biblical Ark of the Covenant, in which lies the “Tablets of Law” upon which the Ten Commandments are inscribed. Menelik is believed to have taken it on a visit to Jerusalem to see his father. It is supposed to reside still in the Church of St Mary in Aksum, though no-one is allowed to set eyes on it. Replicas of the Ark, called Tabots, are housed in all of Ethiopia’s churches, and are carried in procession on special days.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Aksumite Coins

Coins have a unique significance in the history of Aksum. They are particularly important because they provide evidence of Aksum and its rulers. The inscriptions on the coins highlight the fact that Aksumites were a literate people with knowledge of both Ethiopic and Greek languages.

Conversion to Christianity

It is generally thought that the first Aksumite coins were intended for international trade. These coins, bearing the name of King Endybis (c. 270/290 C.E.), were mainly struck in gold and silver and followed the weight standard which existed in the Roman Empire. Initially, the symbols of the crescent and disc, which were common to the religions in South Arabia to which Aksum adhered, were used on early Aksumite coins. But after the conversion of King Ezana around 340–356 C.E., the king made a powerful statement by replacing the existing symbols with a cross which clearly denoted the importance that Christianity now had in the kingdom. The coins also had a portrait of the ruler on the obverse and reverse of the coin along with teff, a local type of wheat. Inscriptions were another form of information included on the coins.

For the most part, gold coins were inscribed in Greek and often intended for exports, while silver and copper coins were insribed in Ge’ez (Aksumite script). From the 4th century C.E., an increasing number of copper coins were issued which had evidently Christian inscriptions such as “Joy and Peace to the People” and “He conquers through Christ.” With the replacement of gold coins with copper ones, the craftsmen of Aksum started using specialized techniques of gilding, which was unique to the kingdom and involved gold leaf being added to crowns and other symbols to enhance the appearance, and most probably the value, of coins.

This coin was minted during the reign of King Joel in sixth-century Aksum. Between the second and the ninth centuries, the kingdom of Aksum prospered in Ethiopia. The trade routes along the Nile Valley that led to the Red Sea and on into the Indian Ocean made Aksum a destination for many merchants and travelers.

The large cross on the reverse of the coin symbolizes the country’s shift to Christianity. This took place during the fourth century when a traveller named Frumentius converted Aksum’s ruler, King Ezana. The old religious symbols of the sun and the moon no longer appeared on coins and were replaced with a cross, which was enlarged over the years.

The religious symbolism on these coins had strong political implications, as it aligned Aksum’s religious identity with its main trading partners, Rome, and later Byzantium.

Suggested readings:

J. Williams (ed.), Money: a history (London, The British Museum Press, 1997).

© Trustees of the British Museum

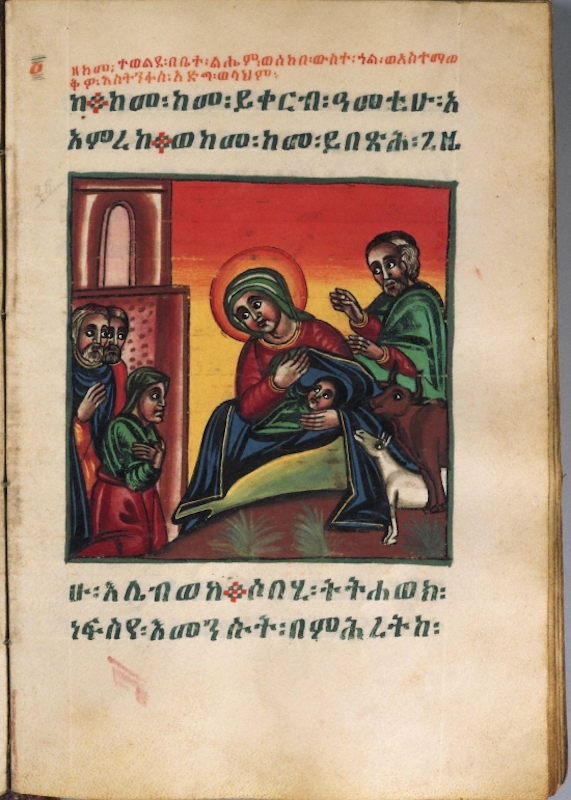

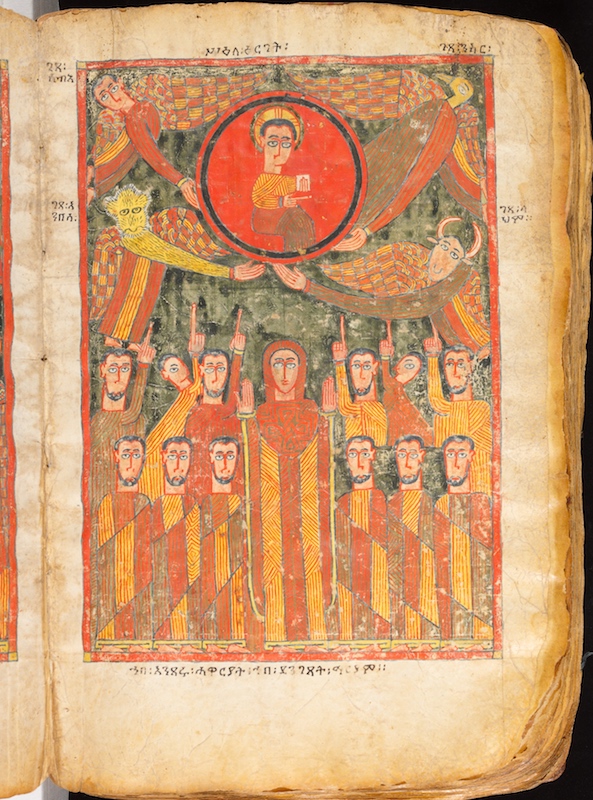

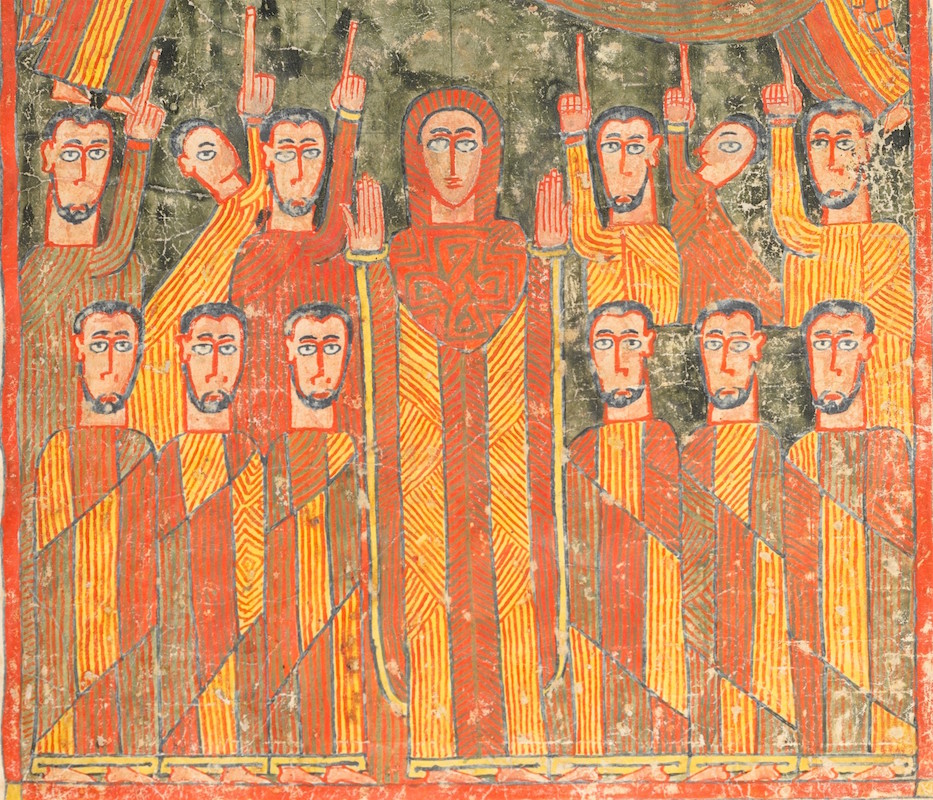

Illuminated Gospel

This full-page illumination is one of twenty-four from a manuscript of the Gospel that reflects Ethiopia’s longstanding Christian heritage. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church was established in the fourth century by King Ezana (who ruled 320–350). He adopted Christianity as the official state religion of Aksum, a kingdom located in the highlands of present-day Ethiopia. As the Christian state expanded over the centuries, monasteries were founded throughout the region. These became important centers of learning and artistic production, as well as influential outposts of state power.

The manuscript was created at a monastic center near Lake Tana in the early fifteenth century. It is composed of 178 leaves of vellum bound between acacia wood covers. The illuminations depict scenes from the life of Christ and portraits of the Evangelists. This text and its pictorial format are based upon manuscripts produced by the Coptic Church. Here, however, these prototypes are transformed into local forms of expression. For example, the imagery is two-dimensional and linear, which is characteristic of Ethiopian painting. Additionally, the text is inscribed not in its original Greek, but in Ge’ez, the ancient liturgical language of Ethiopia. Ge’ez is one of the world’s oldest writing systems and is the foundation of today’s Amharic, Ethiopia’s national language.

In this depiction of the Ascension of Christ into heaven, he appears framed in a red circle at the summit, surrounded by the four beasts of the Evangelists. Below, Mary and the Apostles gesture upward. The stylistic conventions seen here, such as the abbreviated definition of facial features and boldly articulated figures, are consistent throughout the manuscript, suggesting the hand of a single artist. The artist depicts the figures’ heads frontally and their bodies frequently in profile. The use of red, yellow, green, and blue as the predominant color scheme is typical of Ethiopian manuscripts from this period. The images were intended to be viewed during liturgical processions.

The Gospels were considered among the most holy of Christian texts by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Such manuscripts were often commissioned by wealthy patrons for presentation as gifts to churches. While the text demonstrated the erudition of its monastic creator, the elaborate ornamentation reflected the prestige of the benefactors. Many works of Ethiopian art were destroyed by Islamic incursions during the sixteenth century, making this manuscript a rare survivor.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Eastern and Southern Africa on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Prayer Book: Arganonä Maryam (The Organ of Mary) in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Julie Mehretu, Stadia II

Opening / Ceremonies

When looking at Stadia II, first try to isolate the black lines from the rest of the composition. Does this centrifugal structure remind you of a sports arena, an amphitheater or opera house? Perhaps a political chamber? It could denote all of these, broadly invoking our experiences as individuals and collective bodies in such spaces. The built environment, for Mehretu, provides a setting in which people can gather, protest, pray, and riot in mass numbers.

Now, try to imagine yourself in a large stadium, at an important athletic championship such as the FIFA World Cup or the Olympics. How do the crowds behave? What types of phrases or slogans are they shouting, and at what volume? Think about the matching clothing and the painted faces of spectators wearing team colors, or the flags and banners that they wave over their heads.

In her monumental paintings, murals, and works on paper, Julie Mehretu overlays architectural plans, diagrams, and maps of the urban environment with abstract forms and personal notations. The resulting compositions convey the energy and chaos of today’s globalized world. Stadia II is part of a triptych of works created in 2004, and explores themes such as nationalism and revolution as they occur in the worlds of art, sports, and contemporary politics.

Gaze back into the painting and observe the various shards of color floating over the work’s architectural skeleton. The scene, however abstract, could easily represent our visualization of the sports arena. Small circles, dots, and hash marks float through the open space at the center of the composition, resembling the eruption of confetti that announces a winning team’s victory (or, alternately, that of a lucky political candidate on Election Day).

Notice the larger circles, triangles, blocks and parallelograms that float across the upper register. Far from arbitrary, these basic pictorial elements could comprise the designs of nearly any country’s national flag. The cluster of red and blue stripes, for instance, located along the top-right edge of the canvas, resemble the American flag, without necessarily resolving into a perfect match. We may also find corporate logos and religious symbols interspersed throughout; Mehretu is intentional in drawing analogies between these forms and the propagandistic ways in which they are often used.

Lastly, observe the painterly grey marks that seem to rise from the lower and central registers like plumes of smoke. Stadiums and capital buildings can represent triumph, pride and celebration, but they are also common targets for bombings and acts of terror, which are often motivated by a comparable degree of zealousness and ideological fervor.

Process

Mehretu’s working process begins with the projection of maps and diagrams onto the work’s blank surface. From these, the artist makes traces and hash marks that eventually grow into characters and communities. The first layer is coated with an acrylic-and-silica mixture that seals the drawing under a transparent ground. After drying, this ground is itself overlaid with more figures and photographs that are again assimilated into the composition.

The artist describes her final product as containing a “stratified, tectonic geology (…) with the characters themselves buried—as if they were fossils.”1 This distinct sense of temporality serves as a metaphor for history, memory, and the legacies of past cultural epochs that still influence contemporary life.

Utopian Abstraction

While nationalism, sports and global politics are key points of entry into the work, Mehretu also considers art historical precedents for these themes.

Take a look at the orange diamonds at the side edges, the black quadrilaterals interspersed above, or the dynamic red “X” found at the top edge. These lines and shapes are unmistakable references to the Russian constructivist and Bauhaus movements of the early twentieth century, and to artists such as Alexandr Rodchenko, Kasmir Malevich, El Lissitzky, and Wassily Kandinsky. These artists conceived of pure abstraction as a way to wipe clean the slate of history and to promote universalism and collectivity in art, politics and culture.

Mehretu has long explored the use of abstraction in service of revolution and utopian politics throughout the history of Modernist art, “I am (…) interested in what Kandinsky referred to in ‘The Great Utopia’ when he talked about the inevitable implosion and/or explosion of our constructed spaces out of the sheer necessity of agency. So, for me, the coliseum, the amphitheater, and the stadium are perfect metaphoric constructed spaces.”2 These can represent both the organized sterility of institutions and the “chaos, violence, and disorder” of revolution and mass gathering.

Global Networks

Because Mehretu builds her piece from multiple layers of figure and ground alike, the colors, shapes, and planar forms in Stadia II seem to be suspended between surfaces, and are often caught in a swirling motion around the axis of her compositions. The dynamism of the work makes reference to traffic patterns, wind and water currents, migrations, border crossings and travel.

Depicting patterns of movement, Mehretu emphasizes, on one hand, the militarization of bodies moving within and between national (or digital) spaces, and acknowledges the increasing speeds at which the world seems to be moving. Yet, while her compositions might be vertiginous and disorienting at times, we are given a chance to reflect on the potential and importance of such interconnectedness.

Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Mehretu has lived in Michigan, Rhode Island, and Dakar Senegal, and now resides in New York City.

1. Julie Mehretu, quoted in Thelma Golden, “Julie Mehretu’s Eruptive Lines of Flight as Ethos of Revolution,” in Julie Mehretu: The Drawings, ed. Catherine de Zegher and Thelma Golden, New York, NY: Rizzoli, 2007.

2. Julie Mehretu, “Looking Back: Email Interview between Julie Mehretu and Olukemi Ilesanmi, April 2003” in Drawing into Painting, Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center, 2003: 13-14.

Tanzania

Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania

by STEVEN ZUCKER, WORLD MONUMENTS FUND and STEPHEN BATTLE

Video 4.4.1: A conversation with Stephen Battle, World Monuments Fund and Steven Zucker, Smarthistory about the history and architecture of Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania