4.3: A beginner's guide

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147759

Peoples and cultures

Today, Africa is considered to be the cradle of human ancestry, from which we may all trace our descent. Based on the evidence to date, most scientists concur that humankind evolved and modern humans emerged on the African continent. Recent discoveries of cultural artifacts dating back 70,000 years also suggest that the earliest forms of visual expression may be found in Africa. For many thousands of years, Africans have contributed to the cultural heritage of the world, creating masterful works of astonishing innovation and creativity.

Urban centers

Today, over 680 million people live in Africa. Although some regions remain sparsely inhabited, others are densely populated. The West African nation of Nigeria, for example, has one-fifth of the entire continent’s population. About a third of all Africans live in large cities such as Lagos (Nigeria), the continent’s most populous city with 13.5 million people. Other major urban centers in contemporary Africa include Cairo (Egypt), Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo), Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire), Dakar (Senegal), and Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Pretoria (South Africa). The majority of Africans, however, live in more rural areas where their lifestyle centers on agricultural activities.

Climate

In those parts of the continent that are not heavily urbanized, Africa’s geography and climate have especially impacted the development of different artistic traditions. In agricultural communities, seasonal patterns of rainfall and drought affect cultivation and, by extension, their cultural practices. An alternation between rainy and dry seasons is seen throughout much of Africa, in varying degrees. Dry seasons allow opportunities for part-time artisans to create artifacts and for people to organize festivals and other large-scale social events that employ such art forms. Certain areas, such as southwestern Africa and parts of eastern Africa’s interior, also had (and continue to have) frequent droughts. This has forced populations to migrate often or adopt a nomadic lifestyle. As a result, their artistic expression has focused on relatively ephemeral and personal traditions such as body ornamentation, rather than larger scale wooden sculpture.

Diversity

Throughout the continent, there is found a diversity of societies, languages, and cultures. It is estimated that there are well over 1,000 distinct languages in Africa, making it the most linguistically varied of all the continents. In Nigeria alone, more than 250 different languages are spoken. Important regional languages, spoken over broad geographic areas by people of varied ethnicity, include Arabic in northern Africa, Swahili in eastern Africa, and Hausa and Mandinka in parts of western Africa. English, French, and Portuguese were introduced during the colonial period and remain in wide usage today.

A note on language

Culturally, Africans define themselves in many different ways: by occupational caste, village, kinship group, regional origin, and nationality. “Peoples” or “cultures” are the preferred terms when referring to ethnic identities; “tribe”—a word sometimes applied to African peoples or societies—is an inappropriate, even inaccurate term, and should be avoided. Based on a concept developed by nineteenth-century Western social theorists, “tribe” was used to describe a group of people sharing a common language, history, geographic region, and sociopolitical organization. In reality, ethnicity and social identity are much more complex, as Africans may identify themselves in multiple ways. For example, an individual may be simultaneously Nigerian, a resident of the Delta State, Ijo (a broad ethnic designation), and Kalabari (an eastern subgroup of the Ijo). Furthermore, the term “tribe” reflects misleading historical and cultural assumptions, as it often implies a kind of cultural backwardness with derogatory associations.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

For instructors: related lesson plan on Art History Teaching Resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Historical overview: to 1600

Humankind’s origins and the beginnings of cultural expression may be traced to Africa. Recent discoveries in the southern tip of Africa provide remarkable evidence of the earliest stirrings of human creativity. Ocher plaques with engraved designs, made some 70,000 years ago, represent some of humankind’s earliest attempts at visual expression. Although much remains to be learned about Africa’s ancient civilizations through further archaeological research, such discoveries suggest tantalizing possibilities for rich insights into human as well as artistic evolution.

Rock paintings depicting domesticated animals provide artistic evidence of the existence of agricultural communities that developed in both the Sahara region and southern Africa by around 7000 B.C.E. As the Sahara began to dry up, sometime before 3000 B.C.E., these farming communities moved away. In the north, this led to the emergence of art-producing civilizations based along the Nile, the world’s longest river. Egypt, one of the world’s earliest nation-states, was unified as a kingdom by 3100 B.C.E. Further south along the Nile, one of the earliest of the Nubian kingdoms was centered at Kerma in present-day Sudan and dominated trade networks linking central Africa to Egypt for almost one thousand years beginning around 2500 B.C.E.

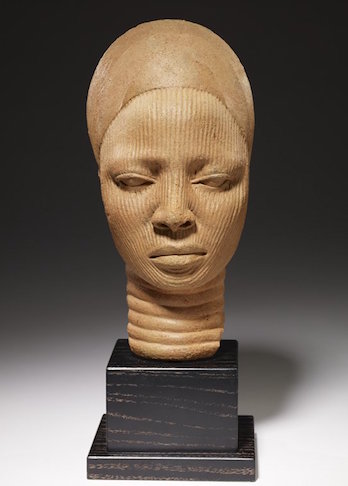

A corpus of sophisticated terracotta sculptures found over a broad geographic area in present-day Nigeria provides the earliest evidence of a settled community with ironworking technology south of the Sahara. The artistic creations of this culture are referred to as Nok, after the village where the first terracotta was discovered, and date to 500 B.C.E. to 200 C.E., a period of time coinciding with ancient Greek civilization. Although Nok terracottas continue to be unearthed, no organized excavations have been undertaken and little is known about the culture that produced these sculptures.

Terracotta heads, buried around 500 C.E., have also been found in north eastern South Africa. These important ancient artistic traditions are underrepresented in Western museums today, including the Metropolitan, due to restrictions regarding the export of archaeological materials.

The first millennium C.E. witnessed the urbanization of a number of societies just south of the Sahara, in the broad stretch of savanna referred to as the western Sudan.

The strategic location of the Inland Niger Delta, lying in a fertile region between the Bani and Niger rivers, contributed to its emergence as an economic and cultural force in the area. Excavations there at the site of Jenne- jeno (“Old Jenne,” also known as Djenne-jeno) suggest the presence of an urban center populated as early as 2,000 years ago. The city continued to thrive for many centuries, becoming an important crossroads of a trans-Saharan trading network. Terracotta figures and fragments unearthed in the region reveal the rich sculptural heritage of a sophisticated urban culture (see the Seated Figure, above).

By the ninth century, trade across the Sahara had intensified, contributing to the rise of large state societies with diverse cultural traditions along trade routes in the western Sudan as well as introducing Islam into the region. Initially traversed by camel caravans beginning around the fifth century, established trans-Saharan trade routes ensured the lucrative exchange of gold mined in southern West Africa and salt from the Sahara, as well as other goods. Ghana, one of the earliest known kingdoms in this region, grew powerful by the eighth century through its monopoly over gold mines until its eventual demise in the twelfth century (see the Linguist Staff, left).

The present-day nation of Ghana takes its name from this ancient empire, although there is no historical or geographic connection.

In the early thirteenth century, the kingdom of Mali ascended under the leadership of Sundiata Keita, who is still revered as a culture hero in the Mande-speaking world. At its height, this Islamic empire, which flourished until the seventeenth century, encompassed an area larger than western Europe and established Africa’s first university in Timbuktu. Under the Songhai empire of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, one of the largest in Africa, the cities of Timbuktu and Jenne (also known as Djenne) prospered as major centers of Islamic learning (image above).

Beyond the kingdoms of the western Sudan, other centers of cultural and artistic activity emerged elsewhere in western Africa. The art of metalworking flourished as early as the ninth century at a site called Igbo-Ukwu, in what is now southern Nigeria. Hundreds of intricate copper alloy castings discovered there provide artistic evidence of a sophisticated and technically accomplished culture.

Nearby to the west, the ancient site of Ife, considered the cradle of Yoruba civilization, emerged as a major metropolis by the eleventh century. Artists working for the royal court in Ife produced a large and diverse corpus of masterful work, including magnificent bronze and terracotta sculptures renowned for their portrait-like naturalism (image left). The rich artistic traditions of the Yoruba continue to thrive in the present day.

The neighboring kingdom of Benin, which traces its origins to Ife, established its present dynasty in the fourteenth century. Over the next 500 years, specialist artisans working for the Benin king created several thousand works, mostly made of luxury materials such as ivory and brass, that offer insights into life at the royal court (image below). Other state societies emerged in the eastern and southern parts of the continent.

The Aksum empire (also known as Axum), one of the earliest Christian states in Africa, flourished from the first century C.E. into the eleventh century, producing remarkable stone palaces and enormous granite funerary monoliths.

Christian faith inspired the artistic creations of later dynasties, including the extraordinary churches of Lalibela hewn from solid rock in the thirteenth century, and the illuminated manuscripts and other liturgical arts of the later Solomonic era.

Notable among the kingdoms that emerged in southern Africa is Mapungubwe in present-day Zimbabwe, a stratified society that arose in the eleventh century and grew wealthy through trade with Muslim merchants along the eastern African coast.

Just to the north are the remains of an ancient city known as Great Zimbabwe, considered one of the oldest and largest architectural structures in sub-Saharan Africa. This massive complex of stone buildings, spread over 1,800 acres, was constructed over 300 years beginning in the eleventh century.

In the fifteenth century, the age of exploration ushered in a period of sustained engagement between Europe and Africa. The Portuguese, and later the Dutch and English, began trade with cities along the western coast of Africa around 1450. They returned from Africa with favorable accounts of powerful kingdoms as well as examples of African artistry commissioned from local sculptors. These exquisitely carved ivory artifacts, now known as the “Afro-Portuguese” ivories, were brought back from early visits to the continent and became part of the curiosity cabinets of the Renaissance nobles who sponsored exploration and trade.

Through trade, African artists were also introduced to new materials, forms, and ideas. Although historically glass and shell beads were made indigenously, trade with Europe in the sixteenth century introduced large quantities of manufactured glass beads that became widely used throughout Africa (see a later example here). European imports of copper and coral made these luxury materials more plentiful, and artists used them in greater quantities (as in the Head of an Oba, above). Artifacts of European manufacture, such as canes and chairs, served as prototypes for the development of new prestige items for regional leaders (as in the Linguist’s Staff, above). Along with goods imported from Europe, the travelers also brought with them their systems of belief, including Christianity. In some cases, such as in the central African kingdom of Kongo, Christianity was embraced and its iconography integrated into the artistic repertoire. In other parts of Africa, the foreign traders themselves were sometimes represented in artworks.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Additional resources:

African Rock Art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Inland Niger Delta on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Igbo-Ukwu on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Ife Terracottas (1000–1400 A.D.)

Origins and Empire: The Benin, Owo, and Ijebu Kingdoms

Mapungubwe (ca. 1050–1270) on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Historical overview: from the 1600s to the present

Western trade with Africa was not limited to material goods such as copper, cloth, and beads. By the sixteenth century, the transatlantic slave trade had already begun, forcibly bringing Africans to the newly discovered Americas. Slavery had existed in Africa (as it did elsewhere in the world) for centuries prior to the sixteenth, and many socially stratified African societies kept slaves for domestic work. The sheer number of slaves traded across the Atlantic, however, was unprecedented, as over 11 million Africans were brought to the Americas and the Caribbean over a period of four centuries. Driven by commercial interests, the slave trade peaked in the eighteenth century with the expansion of American plantation production, and continued until the mid-nineteenth century. While Europeans primarily profited from the slave trade, certain West African kingdoms, like Dahomey, also grew wealthy and powerful by selling captives of war. By the late eighteenth century, the slave trade began to wane as the abolitionist movement grew. Those who survived the forced migration and the notorious Middle Passage brought their beliefs and cultural practices to the New World.

Within this far-flung diaspora, certain cultures—such as the Yoruba and Igbo of today’s Nigeria, and the Kongo from present-day Democratic Republic of Congo—were especially well represented. African slaves brought few, if any, personal items with them, although recent archaeological investigations have yielded early African artifacts, like the beads and shells found at the African burial grounds in New York’s lower Manhattan, which date to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The influence of Africans in the Americas is perhaps best seen in diverse forms of cultural expression that have enriched our society tremendously. Architectural elements such as open-front porches and sloped hip-roofs reflect African influence in the Americas. The religious practices of Haitian Vodou have roots in the spiritual beliefs of Dahomean, Yoruba, and Kongo peoples. Some elements of cuisine in the American South, such as gumbo and jambalaya, derive from African food traditions. Certain musical forms, such as jazz and the blues, reflect the convergence of African musical practices and European-based traditions.

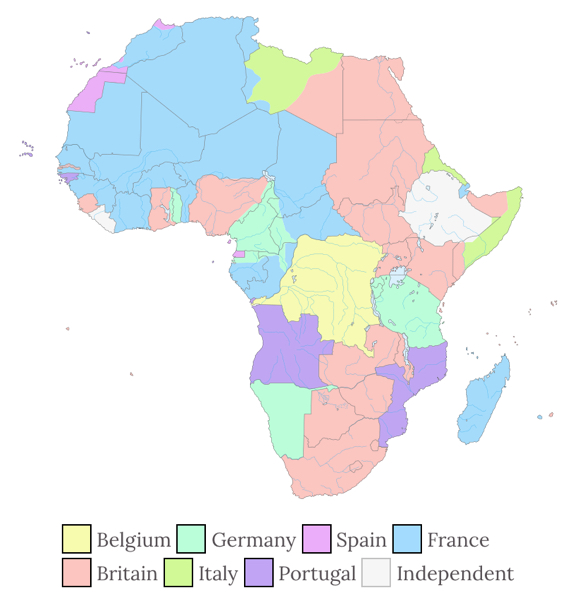

Although the slave trade was banned entirely by the late nineteenth century, European involvement in Africa did not end. Instead, the desire for greater control over Africa’s resources resulted in the colonization of the majority of the continent by seven European countries. The Berlin Conference of 1884–85, attended by representatives of fourteen different European powers, resulted in the regulation of European colonization and trade in Africa. Over the next twenty years, the continent was occupied by France, Belgium, Germany, Britain, Spain, Italy, and Portugal. By 1914, the entire continent, with the exception of Ethiopia and Liberia, was colonized by European nations.

The colonial period in Africa brought radical changes, disrupting local political institutions, patterns of trade, and religious and social beliefs. The colonial era also impacted cultural practices in Africa, as artists responded to new forms of patronage and the introduction of new technologies as well as to their changing social and political situations. In some cases, European patronage of local artists resulted in stylistic change (for example the harp, left) or new forms of expression. At the same time, many artistic traditions were characterized as “primitive” by Westerners and discouraged or even banned.

Although African artifacts were brought to Europe as early as the sixteenth century, it was during the colonial period that such works entered Western collections in significant quantities, forming the basis of many museum collections today. African artifacts were collected as personal souvenirs or ethnographic specimens by military officers, colonial administrators, missionaries, scientists, merchants, and other visitors to the continent. In many of these instances of collecting, objects were gathered through voluntary trade.

In one extreme instance, an act of war initiated by Britain against one of its colonies, thousands of royal art objects were removed from the kingdom of Benin following its defeat by a British military expedition in 1897 (image below). European nations with colonies in Africa established ethnographic museums with extensive collections, such as the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, the Völkerkunde museums in Germany, the British Museum in London, and the Musée de l’Homme in Paris (now housed at the Musée du Quai Branly). In the United States, which had no colonial ties to Africa, the nascent study of ethnography motivated the formation of collections at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Field Museum in Chicago. In 1923, the Brooklyn Museum became the first American museum to present African works as art.

Independence movements in Africa began with the liberation of Ghana in 1957 and ended with the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa during the 1990s. The postcolonial period has been challenging, as many countries struggle to regain stability in the aftermath of colonialism. Yet while the media often focuses on political instability, civil unrest, and economic and health crises, these represent only part of the story of Africa today. From its many urban centers to more tradition-based rural villages, Africa is increasingly entering the global marketplace. The proliferation of systems of communication, such as computers and cell phones, throughout Africa has facilitated increased interaction with other parts of the world. As Africa moves into the twenty-first century, hope lies in its natural and human resources and the commitment of many Africans to work toward a stable and prosperous future.

In spite of Africa’s political, economic, and environmental challenges, the postcolonial period has been a time of tremendous vigor in the realm of artistic production. Many tradition-based artistic practices continue to thrive or have been revitalized. In Guinea, the revival of D’mba performances in the 1990s, after decades of censorship by the Marxist government, is one example of cultural reinvention. Similarly, in recent years, Merina weavers in the highlands of Madagascar have begun to create brilliantly hued silk cloth known as akotofahana, a textile tradition abandoned a century ago.

Photography, introduced on the continent in the late nineteenth century, has become a popular medium, particularly in urban areas. Artists like Seydou Keïta, who operated a portrait studio in Bamako, Mali, in the colonial period, set the stage for later generations of photographers who captured the faces of newly independent African countries. It is also important to mention developments in modern and contemporary African art. During the colonial period, art schools were established that provided training, often based on Western models, to local artists. Many schools were initiated by Europeans, such as the Congolese Académie des Arts, established by Pierre Romain-Desfossé in 1944 in Elisabethville, whose program was based on those of art schools in Europe. Less frequently, the teaching of modern art was initiated by indigenous Africans, such as Chief Aina Onabolu, who is credited with introducing modern art in Nigeria beginning in the 1920s. Since the mid-twentieth century, increasing numbers of African artists have engaged local traditions in new ways or embraced a national identity through their visual expression.

Artists in today’s Africa are the products of diverse forms of artistic training, work in a variety of mediums, and engage local as well as global audiences with their work. In recent decades, contemporary artists from Africa, both self-taught and academically trained, have begun to receive international recognition. Many artists from Africa study, work, and/or live in Europe and the United States. Kenyan-born Magdalene Odundo, for example, was trained as an artist in schools in Kenya and in England, where she now lives. The burnished ceramic vessels she creates, which are purely artistic and not functional, embody her diverse sources, including traditional Nigerian and Kenyan vessels as well as Native American pottery traditions of New Mexico. The work of contemporary African artists like Odundo reveals the complex realities of artistic practice in today’s increasingly global society.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

The Transatlantic Slave Trade on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Frederick Lamp, Frederick. “Art of the Baga: A Drama of Cultural Reinvention.” African Arts 29.4 (1996), pp. 20-33.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Aesthetics

The Role of Visual Expression in Africa

Because many tradition-based African artifacts serve a specific function, Westerners sometimes have not regarded them as art. We need to recognize, however, that the concept of “art for art’s sake” is a relatively recent invention of the Western world. Prior to the Renaissance, most art traditions around the world were considered functional as well as aesthetic. The objects African artists create, while useful, also embody aesthetic preferences and may be admired for their form and composition.

Aesthetics

Artists and patrons in many African societies express well-defined aesthetic preferences and value skillful work. Studies of aesthetics in some African societies have led to the identification of certain artistic criteria for evaluating visual arts. Among the Baule in Côte d’Ivoire, for example, a sculpture of the human figure should emphasize a strong muscular body, refined facial features, and elaborate hairstyle and scarification patterns, all of which reflect cultural ideals of civilized beauty (above and detail left). Scholars of aesthetics in Yoruba (Nigeria) visual expression have identified criteria based on both formal elements, such as a smooth surface, symmetrical composition, and a moderate resemblance to the subject, as well as abstract cultural concepts, such as ase (inner power or life force) and iwa (character or essential nature). Many African societies associate such smooth, finished surfaces with cultivated refinement.

African aesthetics generally have an ethical or religious basis. An artwork considered “beautiful” is often also believed to be “good,” in the sense that it exemplifies and upholds moral values. The fact that, in many societies, the words for beautiful and good are the same suggests a strong correspondence between these two ideas. The ability of an artifact to work effectively, whether that means connecting with the spiritual realm or imparting a lesson to initiates, may also be a standard for determining the “beauty” of an artifact.

Although in the Western world, aesthetics is often equated with beauty, artists in some African cultures create works that are not intended to be beautiful. Such works are deliberately horrific in order to convey their fearsome powers and thereby elicit a strong reaction in the viewer (above).

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The human figure, animals and symbols

The human figure

The human figure is the main subject that traditionally has engaged African artists. African figurative sculpture usually departs from natural proportions. There is often a conceptual basis behind artistic conventions such as the simplification and exaggeration of the human features. For example, in many African artworks, the head appears proportionately larger than the body. This formal emphasis has symbolic meaning, as the head is believed to have a special role in guiding one’s destiny and success in many African societies. African artists also employ scale for symbolic effect in multifigure compositions, a practice known as hierarchical representation. In these cases, the most important individual is depicted as the largest figure, while those of lesser importance decrease in size exponentially (above).

Animals and the Natural World

Animals with special attributes—such as antelopes, snakes, leopards, and crocodiles—are represented in art for symbolic purposes. For example, the nineteenth-century Fon king Guezo is represented by a buffalo, an animal signifying strength and determination, selected as his emblem through fa divination (above). Representations of animals consuming other animals (below) may serve as a metaphor for competing spiritual or social forces. Their depiction is meant to encourage other, less destructive means to resolve a difficult social encounter.

Features of different types of animals may also be combined into new forms that synthesize complex ideas. Among the Bamana, for example, ci wara headdresses are based on the features of various antelope species and may also incorporate those of aardvarks, anteaters, and pangolins, all highly symbolic animals. The resulting synthesis of animal forms evokes the mythic Ci Wara, the divine force conceptualized as half man and half antelope who introduced agricultural methods to the Bamana.

Animal symbols may also take more abstract form. In the Cameroon Grassfields, circular medallions represent spiders, a symbol of supernatural wisdom, and diamond- shaped motifs refer to frogs, which stand for fertility and increase (image 26). Some forms of symbolism in African art use plants as points of reference. On cast plaques from Benin, a background pattern of river leaves is a symbol for Olokun, god of the sea (below).

Other Forms of Symbolism

Symbols may be nonrepresentational. Geometric patterns on Bwa plank masks have multiple levels of meaning that refer to ideals of social and moral behavior taught to initiates (example here). Materials also hold symbolic value. Gold foil used in Asante regalia alludes to the sun and to life’s vital force (example here). Indigenous forms of writing, such as nsibidi used among various cultures in Nigeria’s Cross River region, embody multiple levels of symbolic meaning that can be accessed only by the initiated. Gestures, too, are a form of symbolism (see the example above where painted designs on the forehead and cheeks of the faces represent nsibidi, an indigenous writing). In Kongo art, a seated pose illustrates a dictum about balance, composure, and reflection (example, below), while a protruding tongue refers indirectly to the activation of medicines.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

Essays on African Art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Form and meaning

Abstraction and Idealization

Realism or physical resemblance is generally not the goal of the African artist. Many forms of African art are characterized by their visual abstraction, or departure from representational accuracy. Artists interpret human or animal forms creatively through innovative form and composition. The degree of abstraction can range from idealized naturalism, as in the cast brass heads of Benin kings (below, left), to more simplified, geometrically conceived forms, as in the Baga headdress (below).

The decision to create abstract representations is a conscious one, evidenced by the technical ability of African artists to create naturalistic art, as seen, for example, in the art of Ife, in present-day Nigeria. Idealization is frequently seen in representations of human beings. Individuals are almost always depicted in the prime of life, never in old age or poor health. Culturally accepted standards of moral character and physical beauty are expressed through formal emphasis.

Masks used by the women’s Sande society, for example, present Mende cultural ideals of female beauty (top of page). Instead of a physical likeness, the artist highlights admired features, such as narrow eyes, a small mouth, carefully braided hair, and a ringed neck. Idealized images often relate to expected social roles and emphasize distinctions between male and female.

In Bamana statuary, full breasts and a swelling belly highlight a woman’s role as nurturer (left). At the same time, complementary male and female pairs of figures express the concept of an ideal social unit through matched gestures, stances, and expressions.

Surface

Once an artifact leaves its creator’s hands, its visual appearance may be altered through use in ritual or performance contexts. Repeated handling of an artifact during ceremonies can create a smoothly worn surface, while ritual applications of palm oil may result in a lustrous sheen (example here). During ceremonies, decorative elements, such as beads, metal jewelry, and fabric, can be added to a work. Applications of sacrificial substances and organic materials create an encrusted surface that literally and figuratively empowers an object (example here). Masks and figurative sculptures may also be repainted from one season to the next. Bwa masks, for example, are soaked after the harvest and repainted red, white, and black, generally with natural vegetal or mineral pigments but now also with European enamel paints (example here).

Form and Meaning

While creations by African artists have been admired by Western viewers for their formal power and beauty, it is important to understand these artifacts on their own terms. Many African artworks were (and continue to be) created to serve a social, religious, or political function. In its original setting, an artifact may have different uses and embody a variety of meanings. These uses may change over time. A mask originally created for a particular performance may be used in a different context at a later time. Nwantantay masks, used by the southern Bwa in Burkina Faso, may be performed during burial ceremonies and also for annual renewal rites. Artworks can also have different meanings for different individuals or groups. A sculpture owned by an elite association holds deeper levels of meaning for its members than for the general public, who may understand only its basic meaning. The painted designs on an Ejagham headdress, for example, represent an indigenous form of writing, the meanings of which are restricted to individuals of the highest status and rank (left and above). Understanding the cultural contexts and symbolic meanings of African art therefore enhances our appreciation of its form.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

Headdress: Female Bust (D’mba) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Head of an Oba at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Religion and the Spiritual Realm

Traditional religions in Africa

Most traditional religions in Africa have developed at the local level and are unique to a particular society. Common elements include a belief in a creator god, who is rarely if ever represented in art and directly approached by worshipers. Instead, the supreme deity is petitioned through intermediaries, or lesser spirits. These spirits may be related to the natural world and have control over powerful natural phenomena. For instance, Nwantantay masks used by the Bwa of Burkina Faso represent various flying spirits that inhabit the natural world and can offer protection. These flying spirits are believed to take physical form as insects or water fowl. In Guinea, Baga beliefs describe local water spirits, called Niniganné, associated with both wealth and danger that take symbolic form as snakes. Nature spirits, appealed to by Baule diviners in Côte d’Ivoire for spiritual insights, are conceived of as grotesque beings associated with untamed wilderness (example here).

Other spirits represent founding ancestors, whose activities are described in stories about the creation of the world and the beginnings of human life and agriculture. The Dogon of Mali recount their genesis story with reference to Nommo, a primordial being who guided an ark with the eight original ancestors from heaven to populate the earth (top of page). Also in Mali, Bamana agricultural ceremonies invoke Ci Wara, the half man and half antelope credited with introducing agriculture to humanity (above). The original ancestors in Senufo (Côte d’Ivoire) belief are represented by a monumental pair of male and female figures exemplifying an ideal social unit (example left).

The category of spirits believed to be most accessible to humans is that of recently deceased ancestors, who can intercede on behalf of the living community. Among the Akan in Ghana, ancestors are commemorated by terracotta sculptures that, when placed in a sacred grove near the cemetery, serve as a focal point for funeral rites and a point of contact with the deceased (example here). Fang societies preserved the bones of important deceased individuals in bark containers in the belief that their relics held great spiritual power (example here). In many large states, a living king and leader may be regarded as divine as well. In the kingdom of Benin, in today’s Nigeria, the Oba historically was considered semi-divine and therefore constituted the political and spiritual focus of the kingdom (example here).

Christianity in Africa

In addition to indigenous religions at a local level, other religions are also practiced throughout Africa. Christianity has existed in Egypt and northern Africa since the second century. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church was established in the fourth century by King Ezana, who adopted Christianity as the state religion (example here). In the late fifteenth century, Christianity was introduced into sub- Saharan Africa by Portuguese explorers and traders. Although most African cultures did not adopt the religion, the Kongo king Afonso Mvemba a Nzinga established Christianity as the state religion in the early sixteenth century (example here). During the colonial period, Christianity gained converts throughout the continent.

Islam came to Egypt after 640, then spread below the Sahara in the eighth and ninth centuries through traders and scholars. On the east coast, Arab and Persian colonizers introduced Islam beginning in the eighth century. Although the acceptance of Islam or Christianity sometimes precluded the practice of traditional religions, in many cases they coexisted or were incorporated into preexisting beliefs. The adoption of Islam and Christianity also led to the abandonment of many earlier forms of artistic expression.

Religious practice in Africa centers on a desire to engage the spiritual world in the interests of social stability and well-being. Annual rites of renewal among the Bwa, for example, are designed to seek the continued goodwill of nature spirits (example here). Political leaders also seek religious guidance to ensure the success of their reign. Fon kings, for example, referenced a divination process known as fa, which predicted the nature and character of their reign (example here). Personal misfortune, such as illness, death, or barrenness, or community crises, including war or drought, are also cause to petition the spirits for guidance and assistance. Art objects are employed as vehicles for spiritual communication in diverse ways. Some are created for use in an altar or shrine and may receive sacrificial offerings. The Dogon of Mali, for example, show gratitude to the ancestors by offering pieces of meat in a monumental container presented to the family altar (below). In the kingdom of Benin (Nigeria), cast brass heads commemorating deceased kings are placed on royal ancestral altars, where they serve as a point of contact with the king’s royal ancestors (above).

Other objects are used by diviners to attract and tap into spiritual forces. The dazzling beauty of an expertly carved Baule figure sculpture lures a nature spirit into inhabiting the sculpture, thereby aiding a diviner’s work (example here). Such objects themselves are often not inherently powerful but must be activated through ritual offerings or by a knowledgeable religious specialist.

Fon diviners empower figurative sculptures called bocio with organic substances that ensure their client’s health and well-being (left). Similarly, Kongo ritual objects known as nkisi derive their potency from various substances, both organic and man-made, added to a carved figure by a ritual specialist (example here). The unseen forces of nature or the spiritual world are called upon to serve a variety of purposes, including communicating with the spirits, honoring ancestors, healing sickness, or reinforcing societal standards, through masked performances. Masquerades involve the active participation of dancers, musicians, and even the audience, in addition to the masked dancer, who serves as the vehicle through which these invisible powers become manifest. By donning a mask and its associated costume, the dancer transcends his own identity and is transformed into a powerful spiritual being. Among the Dogon, masks are worn at dama, a collective funerary rite for men whose goal is to ensure safe passage of the deceased’s spirit to the world of the ancestors (example here). Masked performances by members of the Bamana Komo association convey knowledge of their history, beliefs, and rituals to initiated members (example here). The massive sculpted headdress known as D’mba among the Baga is seen as a symbol of cultural reinvention and appears on various occasions marking personal and communal growth (example here). Among the Mende and their neighbors, masquerades of the Sande society encourage and celebrate young female initiates and offer a model of feminine beauty and spiritual power (example here).

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

African Art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Art and Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Seated (Dogon) Couple at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Headdress: Male Antelope (Ci Wara) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Male and Female Poro Altar Figures (Ndeo) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ritual Vessel (Aduno Koro): Horse at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Crucifix from the Democratic Republic of Congo at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Art and Oracle: African Art and Rituals of Divination (ebook from The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Art and politics

Political institutions in Africa that predate European colonization have ranged from large, centralized kingdoms led by a single ruler to smaller, village-based societies. Centralized states may vary in size and complexity but are generally ruled by a chief or king, supported by a hierarchical bureaucracy. In many different societies, leaders are considered to be semi-divine. In less centralized societies, power is not vested in a single individual. Instead, authority may be exercised by family heads, a council of elders, or local social or political institutions. African political institutions were dramatically impacted by colonial rule. The role of traditional rulers continues to change in post-independence Africa, where modern states are governed by national leaders.

In centralized states, leaders have historically played an important role as patrons of the arts. Often, leaders held monopolies over the materials used and controlled artistic production as well (see image above). They commissioned a wide range of prestige objects, distinguished by the lavish use of luxury materials (see below), as well as complex architectural programs (example here). Works made of metal, ivory, or beads were not only visually spectacular, but also reminded the public of the king’s wealth and power. Such art forms underscored the king’s fundamental difference from—and superiority to—his subjects. Royal arts are often used in ceremonial contexts that mark and legitimize political authority. Handheld objects, such as flywhisks, staffs (like the one below), and pipes, are used as personal regalia to indicate rank and position within the court.

Special seats of office and clothes and regalia made of expensive materials (example here) distinguish the leader’s exalted position and set him apart, both literally and figuratively, from his subjects. Larger works legitimize political power to a broad public. Portraits of past leaders document dynastic lines of leadership and serve as a visual reminder of the present king’s legacy like the portrait of an Oba above). Such portraits generally present an idealized depiction of a youthful and vigorous king and emphasize the various trappings of royalty.

Among smaller, village-based societies, in which governance is distributed among local associations, artworks do not glorify a particular leader. Instead of lavish displays of royal regalia, masks and figures are used as agents of social control or education. Such works are generally commissioned by a group of individuals, such as a council of elders or members of a religious association. They give visual form to spiritual forces whose power is enlisted to maintain order and well-being in a community. Sometimes, artworks are deliberately fearsome, employing elements of the natural world considered inherently powerful, such as sacrificial blood or medicinal plants (example above). In other contexts, the sculpture’s imagery presents cultural ideals held collectively by the society (example here).

Additional resources:

African art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Barbara W. Blackmun, Art and Rule in the Benin Kingdom, on Art & Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Michelle Gilbert, Akan Leadership and Ceremony, on Art & Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Kathy Curnow, Benin Kingdom Leadership Regalia on Art & Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Joseph Aurélien Cornet, Kuba Art and Rule on Art & Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Rites of passage

In many African societies, art plays an important role in various rites of passage throughout the cycle of life. These rituals mark an individual’s transition from one stage of life to another. The birth of a child, a youth’s coming of age, and the funeral of a respected elder are all events in which an individual undergoes a change of status. During these transitional periods, individuals are considered to be especially vulnerable to spiritual forces. Art objects are therefore created and employed to assist in the rite of passage and to reinforce community values.

The birth of a child is an important event, not only for a family but for society as well. Children ensure the continuity of a community, and therefore a woman’s ability to bear children inspires awe. Ideals of motherhood and nurturance are often expressed visually through figurative sculpture. Among the Senufo, for example, female figures pay homage to the important roles women play as founders of lineages and guardians of male initiates (example above). The importance of motherhood is symbolized by a gently swelling belly and lines of scarification radiating from the navel, considered the source of life. In other societies, such as the Bamana, figural sculptures are employed in ceremonies designed to assist women having difficulty conceiving (example below). They serve simultaneously as a point of contact for spiritual intercession and as a visual reminder of physical and moral ideals.

Initiation, or the coming of age of a boy or girl, is a transition frequently marked by ceremony and celebration. The education of youths in preparation for the responsibilities of adulthood is often a long and arduous process. Initiation rites usually begin at the onset of puberty.

Boys, and to a lesser extent girls, are separated from their families and taken to a secluded area on the outskirts of the community where they undergo a sustained period of instruction and, more typically in the past than now, circumcision. At the conclusion of this mentally and physically rigorous period, they are reintroduced to society as fully initiated adults and given the responsibilities and privileges that accompany their new status.During initiation, artworks protect and impart moral lessons to the youths. The spiritual forces associated with this period of transformation are often given visual expression in the form of masked performances.

During the initiation of boys, male dancers wearing wooden masks may make several appearances. Their performances can serve diverse purposes—to educate boys about their future social role, to bolster morale, to impress upon them respect for authority, or simply to entertain and relieve stress. The initiation of girls rarely includes the use of wooden masks, focusing more on transforming the body through the application of pigment.

The women’s Sande society, found among the Mende and their neighbors, is one of the few organizations in which women wear wooden masks as part of initiation ceremonies (example here). Many initiation organizations continue in today’s Africa, often adapting to contemporary lifestyles. For example, in the past, the Sande society’s initiation process could take months to complete; now, Sande sessions have adapted to the calendars of secondary schools and initiation may be completed during vacation and holiday periods.

In many African societies, death is not considered an end but rather another transition. The passing of a respected elder is a time of grief and lamentation but also celebration. In this final rite of passage, the deceased joins the realm of the honored ancestors. While the dead are buried soon after death, a formal funeral often takes place at a later time. Funeral ceremonies with masked performances serve to celebrate the life of an individual and to assist the soul of the deceased in his or her passage from the human realm to that of the spirits (example here). Such ceremonies generally mark the end of a period of mourning and may be collective, honoring the lives of the deceased over a number of years.

Figurative sculpture is also employed to commemorate important ancestors. Representations of the deceased, individualized through details of hairstyle, dress, and scarification, serve not only as memorials but also as a focal point for rituals communicating with ancestors (example here). In some central African societies, certain bones of the deceased are believed to contain great power and are preserved in a reliquary. In such cases, figurative sculpture attached to the reliquary does not represent the ancestor but honors and amplifies the power of the sacred relics (example above).

Additional resources:

Manuel Jordan, Art and Initiation in Western Zambia on Art & Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Art and the individual

While many kinds of African art are employed in communal contexts, others serve the needs of individuals. Domestic furnishings and objects of personal use, while practical in purpose, also have an aesthetic dimension. The artistic enhancement of objects of utilitarian function reflect and reinforce an individual’s standing and status in society. Details of form and decoration personalize an object, marking it as the property of a specific individual and, occasionally, providing information about ethnic affiliation, social status, or rank. At the same time, the artistic inventiveness and careful execution of such works clearly indicate a desire to integrate aesthetics into daily life.

Personal adornment and dress are important forms of aesthetic expression. Scarification and hairstyle, in particular, are regarded by Africans as means by which the body is refined and civilized. Specifics of bodily ornamentation are often depicted in fine detail on masks and figurative sculpture, indicating their importance as symbols of cultural, personal, and/or professional identity (example above). Dress is also a means of self-expression and definition. Certain forms of textiles identify the wearer by age or status and may also convey personal identity as well (example below). Textiles have also historically been conceived as a form of wealth and their extensive use comments upon the wearer’s access to riches.

Additional resources:

Tutsi Basketry on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Rachel Hoffman, Textiles in Mali on Art & Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Fred T. Smith, Frafra Leatherwork and Brass Bangles on Art & Life in Africa (University of Iowa)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

African art and the effects of European contact and colonization

by DR. PERI KLEMM

Early encounters with Europeans were often recorded in African art. Look closely at the top of the mask above (and detail, left). Do you see faces? These represent Portuguese explorers with beards and hats (flanked by mudfish) who visited the Benin Kingdom along the west coast of Africa in the late 1400s. These explorers began to collect ivory which they referred to as “white gold.”

Saltcellars like the one below, commissioned by Portuguese officers and exquisitely produced by West African carvers, held precious table salt. They would have been taken back to Portugal to be displayed in curiosity cabinets. Today their carvings serve as a record of the introduction of guns, Christianity, and European commodities to West Africa.

By the 1880s European powers were interested in Africa’s resources, particularly mineral wealth and forests. Today, Africa is divided into 53 independent countries but many scholars argue that the boundaries that separate these countries are really artificial. They were drawn by Europeans at the Berlin Conference in 1884-85 without a single African present. They did not divide the continent by cultural or tribal region, but instead created borders based on their own interests. The problems this created—separating families, language groups, trading partners, pastoralists from watering holes, etc.—are still very much at issue today.

Movements in African History and Art

African cultures never existed in isolation—there was always movement, trade, and the exchange of ideas. And logically African art is dynamic and has changed in form, function, and meaning over time. Nevertheless, in the Western art market and in academia, there exists the concept of “traditional” African art. Usually this refers to “indigenous art traditions that were viable and active prior to the colonization of Africa by European powers in the late nineteenth century. Implicit in the use of the word traditional is the assumption that the art which it describes is static and unchanging.”[1] Many collectors and museum professionals place far greater value on African objects created prior to colonization. For them, pre-colonial objects have an aura of an untainted, timeless past when artists only made artworks for their own communities unaffected by the outside world. These objects are too often seen in opposition to work produced today using Western materials and conventions by artists who are engaged in a global discourse and who make works of art to be sold.

In reality, some African art has always functioned as a commodity and artists have always drawn inspiration and materials from outside sources. While many auction houses and art museums clearly differentiate between “traditional” African art created prior to the colonial period and artwork created during and after colonization, African art historians are beginning to dispel this simplistic division and instead, ask their audiences to recognize the continuity and dynamism of African art. Looking closer, scholars find that specific historical moments had a profound affect on African communities and their art. During the slave trade and colonization, for example, some artists created work to come to terms with these horrific events—experiences that often stripped people of their cultural, religious and political identities.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade

One of the most damaging experiences for many ethnic groups in Africa was the transatlantic slave trade. While slavery had long existed in Africa, the transatlantic slave trade constituted a mass movement of peoples over four and a half centuries to colonies in North and South America. Ten million people were taken to labor on cotton, rum, and sugar plantations in the new world. Slavery coupled with the colonial experience had a profound effect on Africa and still causes strife. For example, Ghana has over 80 ethnic groups and during slave raids, different groups were pitted against one another—those living near the coast were involved in slave raiding in the interior in exchange for Portuguese and Dutch guns. Territorial disputes, poverty, famine, corruption, and disease increased as a result of the brutality of the slave trade and European colonization.

The Colonial Period

With the collapse of the Atlantic slave trade in the 19th century, European imperialism continued to focus on Africa as a source for raw materials and markets for the goods produced by industrialized nations. Africa was partitioned by the European powers during the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, a meeting where not a single African was present. The result was a continent defined by artificial borders with little concern for existing ethnic, linguistic, or geographic realities.

European nations claimed land in order to secure access to the natural resources they needed to support rapidly growing industrial economies. Once European nations secured African territories, they embarked on a system of governance that enforced the provision of natural resources— with dire consequences for people and the environment.

Resistance to colonial rule grew steadily and between 1950 and 1980, 47 nations achieved independence; but even with independence the problems associated with the slave trade and colonialism remained. The introduction of Christianity and the spread of Islam in the 19th and 20th century also transformed many African societies and many traditional art practices associated with indigenous religions declined. In addition, as imported manufactured goods entered local economies, hand-made objects like ceramic vessels and fiber baskets were replaced by factory-made containers. Nevertheless, one way people made sense of these changes was through art and performance. Art plays a central role, particularly in oral societies, as a way to remember and heal. As African artists began catering to a new market of middle-class urban Africans and foreigners, new art-making practices developed. Self-taught and academically trained painters, for example, began depicting their experiences with colonialism and independence; as fine artists, their work is largely secular in content and meant to be displayed in galleries or modern homes (for example, see the work of Cheri Samba, Jane Alexander, and Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu).

Globalization Today

The diverse and complex systems now at play as a result of globalization are having a profound impact on Africa. Some scholars argue that globalization will have even greater consequences than the slave trade and colonization in terms of population movement, environmental impact, and economic, social and political changes. Whatever the result, these stresses will be chronicled by the continent’s many brilliant artists.

[1] Judith Perani and Fred T. Smith, The Visual Arts of Africa: Gender, Power, and Life Cycle Rituals (Prentice Hall, 1998) p. xvii.

The Reception of African Art in the West

by DR. PERI KLEMM

When early European explorers brought back souvenirs from their trips to the African continent they were regarded as curiosities and they didn’t find a home in art museums for centuries. Instead, these objects became part of natural history museums—along with fossilized remains, flora and fauna, and purely utilitarian objects. They were considered the man-made material remains of a culture. Clouded by the framework of Social Darwinism in the 19th century and other beliefs that justified racial hierarchies, peoples of African, Pacific, and Native American descent were regarded as less civilized, even less human. Attitudes about their art were also determined by pre-conceived ideas about race and therefore, their creations were not categorized as “Art” in Euro-American sense.

By the early 1900s however, these same objects that were initially regarded as artifacts of material culture, began to be exhibited in Western art museums and galleries as “art.” The objects themselves had not changed, but there was a shift in the attitudes and assumptions about what constituted a work of art.

To historicize this issue more, we can divide the history of the display and reception of African art into four periods. In the eighteenth century, objects like the ones illustrated here would likely be housed in a “curiosity cabinet”—in a private family parlor where trinkets and novelties acquired over generations, often while traveling, were displayed. The artist, culture, and function of these objects was not usually recorded or regarded as significant. By the nineteenth century, many of these curiosity cabinet collections were donated first to natural history museums where they were categorized and classified in the name of science along with flora, fauna, and skeletal remains. By the twentieth century, some of these same works were exhibited in fine art galleries and museums. Over time, African art has become widely collected and ever more popular.

Some of the assumptions about what constitutes art is still very much a part of the Western aesthetic system. For example, “high art” is still thought of as painting and sculpture. Because many African artworks served a specific function, Westerners have sometimes not regarded these as art. It is worth remembering, however, that the concept of “art” divorced from ritual and political function, is a relatively recent development in the West. Prior to the 18th century, most artistic traditions around the world were functional as well as aesthetic, and arguments can be made that all art serves social and economic functions. The objects that African artists create—while useful—embody aesthetic preferences and may be admired for their form, composition and invention.

Eighteenth-century theories

In Eighteenth-century Europe, philosophers and critics constructed a definition of “art” in which the object was unique, complex, irreplaceable, inspired by the natural world, and with the exception of architecture, non-functional. In contrast, non-Western art was viewed as not unique, simply produced, replaceable, abstract, and utilitarian. Therefore, Non-Western art was not considered to be art.

Nineteenth-century theories

Nineteenth century notions of art were redefined by theories of cultural evolution. Social Darwinism was used to support the claim that all cultures progress along an evolutionary ladder. Western culture was seen as the most advanced and inherently superior. Societies in Africa were viewed as more primitive, a state of being from which modern Western society evolved. Franz Boas in 1927 in his book Primitive Art shows that cultural evolutionism is seriously flawed. He argued that contemporary societies cannot be arranged on a ladder of “least evolved” or “most advanced.” Nor can their art.

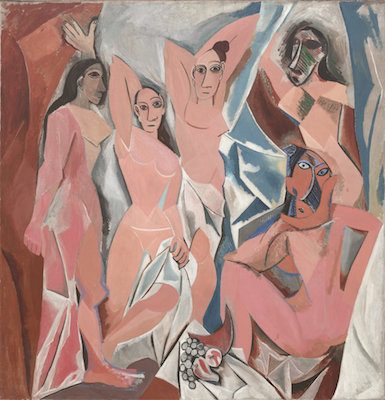

Twentieth-century-cultural relativism and Pablo Picasso

Anthropologists and art historians came to realize that non-Western cultures should not be judged according to the values of the West, leading to a reevaluation of the nature of “art.” However, it was modern Western artists who brought non-Western objects into the popular imagination as works of art worthy of aesthetic consideration. Looking for a new way to represent modernity, artists such as Andre Derain, Amedeo Modigliani, and Pablo Picasso turned to non-Western art for stylistic inspiration. We see this in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (above). The women’s faces on the right of the canvas have been painted as masks inspired by African artworks Picasso observed on his trip to the Trocadero Museum in Paris in 1907:

All alone in that awful museum with masks, dolls made by the redskins, dusty manikins. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon must have come to me that very day, but not at all because of the forms; because it was my first exorcism painting — yes absolutely!…The masks weren’t just like any other pieces of sculpture. Not at all. They were magic things. But why weren’t the Egyptian pieces or the Chaldean? We hadn’t realized it. ‘Those were primitive, not magic things. The Negro pieces were mediators. They were against everything — against unknown, threatening spirits. I always looked at fetishes. I understood; I too am against everything. I understood what the Negroes used their sculpture for. Why sculpt like that and not some other way? After all, they weren’t Cubists! Since Cubism didn’t exist.

In the quote above, Picasso recognized that the African and Amerindian artists whose work he saw at the museum in Paris were deliberately using abstraction. He doesn’t focus on why they chose this style but he adopts it, none-the-less, to pursue his own expressive interests. For contemporary avant-garde artists, African art offered abstraction as a strategy for the representation of modernity. The quote also tells us that Picasso, like many Western collectors, didn’t know much about the function, culture, or history of African objects and he seems to have focused on their purely formal properties. Picasso, Piet Mondrian, Constantin Brancusi, Georges Braque and other modernists helped Western viewers to see these objects as “art” but the cultural meanings of these works remained opaque. However, over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, scholars began to question social Darwinism and seek out indigenous interpretations of the form and function of objects.

Today, many contemporary African artists are influenced by tradition-based African art (see for example, El Anatsui). African arts played a central role in their communities, whether to communicate royalty, sacrality, inner virtues, aesthetic interests, genealogy, or other concerns. As the art historian Robert Farris Thompson has argued for the Yoruba, African art is used to make things happen, it is efficacious and necessary for events like rituals, masquerades, and life cycle transitions to successfully occur.

Western appreciation of African art

The appreciation of African art in the Western world has had an enormous impact not only on the development of modern art in Europe and the United States, but also on the way African art is presented in a Western museum setting. Although objects from Africa were brought to Europe as early as the fifteenth century, it was during the colonial period that a greater awareness of African art developed. The cultural and aesthetic milieu of late-nineteenth-century Europe fostered an atmosphere in which African artifacts, once regarded as mere curios, became admired for their artistic qualities.

African sculpture, in particular, served as a catalyst for the innovations of modernist artists. Seeking alternatives to realistic representation, Western artists admired African sculpture for its abstract conceptual approach to the human form. For example, the powerfully carved Fang reliquary figure (right), with its bulbous and fluid forms, attracted the attention of the painter André Derain and the sculptor Jacob Epstein, both of whom once owned the sculpture.

Increasing interest among artists and their patrons gradually brought African art to prominence in the Western art world. Along with this growing admiration for African art, the aesthetic preferences of collectors and dealers resulted in the development of distinctions between art and artifact. Masks and figurative statuary in wood and metal—genres and media most readily assimilated into established categories of fine art in the West—were preferred over more overtly utilitarian objects, such as vessels or staffs. Masks and figurative statuary are more commonly found in western and central Africa. The legacy of early Western taste, with its emphasis on sculptural forms such as masks and figures, continues to inform most museum collections of African art.

As African art became more widely appreciated in the West, scholars began to study both its stylistic diversity and the meanings that African artifacts hold for their makers. Our understanding of African art has been shaped by the work of anthropologists and art historians, many of whom have spent considerable time doing research in Africa on specific cultural traditions. African scholars are also undertaking research into their own heritage. Their sustained commentaries have led to new information and insights, providing a better understanding of the complex cultural meanings embodied in art. At the same time, scholars today recognize that interpreting the creation, form, and use of African art is an inexact science, as meanings and functions shift over time and across regions.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: