Now that you have planned your research project, you are ready to begin the research. This phase can be both exciting and challenging. As you read this section, you will learn ways to locate sources efficiently, so you will have enough time to read the sources, take notes, and think about how to use them in your research paper. In addition to finding sources, research entails determining the relevance and reliability of sources, organizing findings, as well as deciding whether and how to use sources in your paper. The technological advances of the past few decades—particularly the rise of online media—mean that, as a twenty-first-century student, you have countless sources of information available at your fingertips. But how can you tell whether a source is reliable? This section will discuss strategies for finding and evaluating sources so that you can be a media-savvy researcher.

Depending on your assignment, you will likely search for sources by using

- Internet search engines to locate sources freely available on the web.

- A library’s online catalog to identify print books, ebooks, periodicals, DVDs, and other items in the library’s collection. The catalog will help you find journals by title, but it will not list the journal’s articles by title or author.

- Online databases to locate articles, ebooks, streaming videos, images, and other electronic resources. These databases can also help you identify articles in print periodicals.

Your instructor, as well as writing tutors and librarians, at your college can help you determine which of these methods will best fit your project and learn to use the search tools available to you. You can also find research guides and tutorials on library websites and YouTube channels that can help you identify appropriate research tools and learn how to use them. As you gather sources, you will need to examine them with a critical eye. Smart researchers continually ask themselves two questions: “Is this source relevant to my purpose?” and “Is this source reliable?” The first question will help you avoid wasting valuable time reading sources that stray too far from your specific topic and research questions. The second question will help you find accurate, trustworthy sources.

Writing at Work

Businesses, government organizations, and nonprofit organizations produce published materials that range from brief advertisements and brochures to lengthy, detailed reports. In many cases, producing these publications requires research. A corporation’s annual report may include research about economic or industry trends. A charitable organization may use information from research in materials sent to potential donors. Regardless of the industry you work in, you may be asked to assist in developing materials for publication. Often, incorporating research in these documents can make them more effective in informing or persuading readers.

Identifying Primary and Secondary Sources

When you chose a paper topic and determined your research questions, you conducted preliminary research to stimulate your thinking. Your research plan included some general ideas for how to go about your research—for instance, interviewing an expert in the field or analyzing the content of popular magazines. You may even have identified a few potential sources. Now it is time to conduct a more focused, systematic search for informative primary and secondary sources. Writers classify research resources in two categories: primary sources and secondary sources.

Primary sources are direct, firsthand sources of information or data. For example, if you were writing a paper about the First Amendment right to freedom of speech, the text of the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights would be a primary source. Other primary sources include the following:

- Data

- Works of visual art

- Literary texts

- Historical documents such as diaries or letters

- Autobiographies, interviews, or other personal accounts

Secondary sources discuss, interpret, analyze, consolidate, or otherwise rework information from primary sources. In researching a paper about the First Amendment, you might read articles about legal cases that involved First Amendment rights, or editorials expressing commentary on the First Amendment. These sources would be considered secondary sources because they are one step removed from the primary source of information. The following are examples of secondary sources:

- Literary criticism

- Biographies

- Reviews

- Documentaries

- News reports

Your topic and purpose determine whether you must cite both primary and secondary sources in your paper. Ask yourself which sources are most likely to provide the information that will answer your research questions. If you are writing a research paper about reality television shows, you will need to use some reality shows as a primary source, but secondary sources, such as a reviewer’s critique, are also important. If you are writing about the health effects of nicotine, you will probably want to read the published results of scientific studies, but secondary sources, such as magazine articles discussing the outcome of a recent study, may also be helpful.

Some sources could be considered primary or secondary sources, depending on the writer’s purpose for using them. For instance, if a writer’s purpose is to inform readers about how the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation has affected elementary education in the United States, then a Time magazine article on the subject would be a secondary source. However, suppose the writer’s purpose is to analyze how the news media has portrayed the effects of NCLB. In that case, articles about the legislation in news magazines like Time, Newsweek, and US News & World Report would be primary sources. They provide firsthand examples of the media coverage the writer is analyzing.

Once you have thought about what kinds of sources are most likely to help you answer your research questions, you may begin your search for sources. The challenge here is to conduct your search both efficiently and thoroughly. On the one hand, effective writers use strategies to help them find the sources that are most relevant and reliable while steering clear of sources that will not be useful; on the other hand, they are open to pursuing different lines of inquiry that come up along the way than those that seemed relevant at the start of research. As a process of discovery, good research requires critical thinking about, and often revising of, writers’ plans and ideas.

Reading Popular and Scholarly Periodicals

When you search for periodicals, be sure to distinguish among different types. Mass-market publications, such as newspapers and popular magazines, differ from scholarly publications in their accessibility, audience, and purpose. Newspapers and magazines are written for a broader audience than scholarly journals. Their content is usually quite accessible and easy to read. Trade magazines that target readers within a particular industry may presume the reader has background knowledge, but these publications are still reader-friendly for a broader audience. Their purpose is to inform and, often, to entertain or persuade readers as well.

Scholarly or academic journals are written for a much smaller and more expert audience. The creators of these publications are experts in the subject and assume that most of their readers are already familiar with the main topic of the journal. The target audience is also highly educated. Informing is the primary purpose of a scholarly journal. While a journal article may advance an agenda or advocate a position, the content will still be presented in an objective style and formal tone. Entertaining readers with breezy comments and splashy graphics is not a priority.

Because of these differences, scholarly journals are more challenging to read. That doesn’t mean you should avoid them. On the contrary, they can provide in-depth information unavailable elsewhere. Because knowledgeable professionals carefully review the content before publication in a process called “peer-review,” scholarly journals are far more reliable than much of the information available in popular media. Seek out academic journals along with other resources. Just be prepared to spend a little more time processing the information.

Writing at Work

Periodicals databases are not just for students writing research papers. They also provide a valuable service to workers in various fields. The owner of a small business might use a database such as Business Source Premiere to find articles on management, finance, or trends within a particular industry. Health care professionals might consult databases such as MedLine to research a particular disease or medication. Regardless of what career path you plan to pursue, periodicals databases can be a useful tool for researching specific topics and identifying periodicals that will help you keep up with the latest news in your industry.

Using Sources from the Open Web

When faced with the challenge of writing a research paper, some students rely on popular search engines, such as Google, as their only source of information. Typing a keyword or phrase into a search engine instantly pulls up links to dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of related websites—what could be easier? While the Web is useful for retrieving information, you should be wary of limiting your research to sources from the open Web.

For example, wikis, including online encyclopedias, such as Wikipedia, and community-driven question-and-answer sites, such Yahoo Answers, are very easy to access on the Web. They are free, and they appear among the first few results when using a search engine. Because these sites are created and revised by a large community of users, they cover thousands of topics, and many are written in an informal and straightforward writing style. However, these sites may not have a reliable control system for researching, writing, and reviewing posts. While wikis may be a good starting point for finding other, more trustworthy, more fully developed sources, usually they should not be your final sources.

Despite its apparent convenience, researching on the open Web has the following drawbacks to consider:

- Results do not consider the reliability of the sources. The first few hits that appear in search results often include sites whose content is not always reliable. Search engines cannot tell you which sites have accurate information.

- Results may be influenced by popularity or advertisers. Search engines find websites that people visit often and list the results in order of popularity rather than relevance to your topic.

- Results may be too numerous for you to use. Search engines often return an overwhelming number of results. Because it is difficult to filter results for quality or relevance, the most useful sites may be buried deep within your search results. It is not realistic for you to examine every site.

- Results do not include many of the library’s high quality electronic resources that are only available through password-protected databases or on campus.

- Because anyone can publish anything on the Web, the quality of the information varies greatly and you will need to evaluate web resources carefully.

Nevertheless, a search on the open Web can provide a helpful overview of a topic and may pull up genuinely useful sources. You may find specialized search engines recommended on your college library’s website. For example, http://www.usa.gov will search for information on United States government websites. If you are working at your personal computer, use the Bookmarks or Favorites feature of your web browser to save and organize sites that look promising.

To get the most out of a search engine, use strategies to make your search more efficient. Depending on the specific search engine you use, the following options may be available:

- Limit results to websites that have been updated within a particular time frame.

- Limit results by language or region.

- Limit results to scholarly works available online. Google Scholar is an example.

- Limit results by file type.

- Limit results to a particular site or domain type, such as .edu (school and university sites) or .gov (government sites). This is a quick way to filter out commercial sites that often lead to less objective results.

Information accessible through a college library comes in a variety of types and formats of sources. Books, DVDS, and various types of periodicals can be found in physical form at the library. Many of these same materials are available in electronic format in the form of ebooks, electronic journal articles, and streaming videos. Your college library may have some resources in both print and electronic formats while others may be available exclusively in one format. The following lists different types of resources available at college libraries. In addition to the resources noted, library holdings may include primary sources such as historical documents, letters, diaries, and images.

Types of sources

- Reference works provide a summary of information about a particular topic. Almanacs, encyclopedias, atlases, medical reference books, and scientific abstracts are examples of reference works. In most cases, reference books may not be checked out of a library. Note that reference works are many steps removed from original primary sources and are often brief, so these should be used only as a starting point when you gather information.

- Examples: The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2010; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, published by the American Psychiatric Association.

- Nonfiction books provide in-depth coverage of a topic. Trade books, biographies, and how-to guides are usually written for a general audience. Scholarly books and scientific studies are usually written for an audience that has specialized knowledge of a topic.

- Examples: The Low-Carb Solution: A Slimmer You in 30 Days; Carbohydrates, Fats and Proteins: Exploring the Relationship Between Macronutrient Ratios and Health Outcomes.

- Periodicals are published at regular intervals—daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly. Newspapers, magazines, and academic journals are different kinds of periodicals. Some periodicals provide articles on subjects of general interest while others are more specialized.

- Examples: The New York Times; PC Magazine; JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association.

- Government publications by federal, state, and local agencies publish information on a variety of topics. Government publications include reports, legislation, court documents, public records, statistics, studies, guides, programs, and forms.

- Examples: The Census 2000 Profile; The Business Relocation Package, published by the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce.

- Business publications and publications by nonprofit organizations are designed to market a product, provide background about the organization, provide information on topics connected to the organization, or promote a cause. These publications include reports, newsletters, advertisements, manuals, brochures, and other print documents.

- Examples: a company’s instruction manual explaining how to use a specific software program; a news release published by the Sierra Club.

- Documentaries are the moving-image equivalent of nonfiction books. They cover a range of topics and can be introductory or scholarly. Newsreels can be primary sources about then-current events. Feature-length programs or episodes of a series can be secondary sources about historical phenomena or life stories. You may view a documentary in a movie theater, on television, on an open website, or in a subscription-accessed database such as Films on Demand.

- Examples: Freedom Riders, directed by Stanley Nelson; Finding Your Roots, with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

As you gather information, strive for a balance of accessible, easy-to-read sources and more specialized, challenging sources. Relying solely on lightweight books and articles written for a general audience will drastically limit the range of useful, substantial information. However, restricting oneself to dense, scholarly works could make the research process overwhelming. An effective strategy for unfamiliar topics is to begin your reading with works written for the general public, and then move to more scholarly works as you learn more about your topic.

Using Databases

While library catalogs can help you locate print and electronic book-length sources, as well as some types of non-print holdings, such as CDs, DVDs, and audiobooks, the best way to locate shorter sources, such as articles in magazines, newspapers, and journals, is to search online databases accessible through a portal to which your college’s library subscribes. In many cases, the full texts of articles are available from these databases. In other instances, articles are indexed, meaning there is a summary and publication information about the article, but the full text is not immediately available in the database; instead, you may find the indexed article in a print periodical in your college’s library holdings, or you can submit an online request for an interlibrary loan, and a librarian will email a digitized copy of the article to you.

When searching for sources using a password-protected portal, it’s important to understand where and how to look up your topic. If you don’t find useful sources using the portal’s general search bar, then you may retrieve better results by going to specific databases within the portal. You can choose specific databases by going to “Databases A-Z” or “Databases by Subject.” Databases may be general, including many types of resources on a broad range of subjects, or they may be specialized, focusing on a particular format of resource or a specific subject area. The following list describes some commonly used indexes and databases accessible through libraries’ research portals.

- Academic Search Complete includes articles on a wide variety of topics published in various forums, both scholarly and popular.

- Opposing Viewpoints includes articles, statistics, and recommended websites related to a wide range of controversial issues.

- CQ Researcher Online has full-text articles about issues in the news.

- Lexis Nexis has articles from newspapers and other periodicals, news transcripts, and business and legal information.

- Business Source Complete comprises business-related content from magazines, journals, and trade publications.

- Films on Demand has streaming video of documentaries and historic newsreels.

- Artstor has high-quality images of works of visual art of various media, as well as information on the creators, subjects, materials, and holdings of artworks.

- JSTOR includes full-text scholarly secondary sources, including books and articles, as well as primary sources on a wide variety of topics, mostly in the humanities and social sciences.

- History Reference Center has full-text articles from reference books, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, as well as images and streaming videos on most of the world’s cultures and time periods.

- Literature Resource Center includes full-text print and electronic sources relevant to literature, such as biographies of authors, reviews of works, overviews of plots and characters, analyses of themes, and scholarly criticism.

- Science and Technology Collection has full-text articles from journals in various scientific and technical fields.

- MEDLINE, Proquest Nursing, and Consumer Health Source contain articles in medicine and health.

Sometimes you will know exactly which source you are looking for, for example, if your instructor or another writer references that source. Having the author (if available), title, and other information about the source included in an end-of-text citation will help you to find that source.

As you go through the process of gathering sources, you will likely need to find specific sources referenced by others to build your list of useful sources; use the steps above to help you do this. However, keep in mind that, especially when you first start researching, you will also need to find sources about your topic having little or no idea what sources are out there. Therefore, rather than authors and titles, you will need to enter keywords, or subject search terms, related to your topic. The next section instructs you on how to do that.

Entering Search Terms

One of the most important steps in conducting research is to “learn how to speak database.” To find reliable sources efficiently, you must identify single words or phrases that represent the major concepts of your research—that is, your keywords, or subject search terms. Your starting points for developing search terms are the topic and the research questions you identify, but you should also think of synonyms for those terms. Furthermore, as you begin searching for sources, you should notice additional terms in the subjects listed in the records of your results. These subjects will help you find additional sources.

As Jorge used his library’s catalog and databases, he worked to refine his search by making note of subjects associated with sources about low-carb dieting. His search helped him to identify the following additional terms and related topics to research:

- Low-carbohydrate diet

- Insulin resistance reducing diets

- Glycemic index

- Dietary carbohydrates

Searching the library’s online resources is similar in many ways to searching the Internet, except some library catalogs and databases require specific search techniques. For example, some databases require that you use Boolean operators to connect your search terms. In other databases, Boolean operators are optional, but can still help you get better search results. Here are some of the ways you can use Boolean operators:

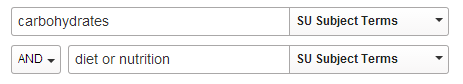

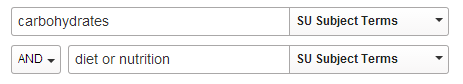

- Connect keywords with AND to limit results to citations that include both keywords—for example, carbohydrates AND diet.

- Connect keywords with OR to search for results that contain either of two terms. For example, searching for diet OR nutrition locates articles that use “diet” as a keyword as well as articles that use “nutrition” as a keyword.

- Connect keywords with NOT to search for the first word without the second. This can help you eliminate irrelevant results based on words that are similar to your search term. For example, searching for obesity NOT childhood locates materials on obesity but excludes materials on childhood obesity.

- Enclose a phrase in quotation marks to search for an exact phrase, such as “morbid obesity.”

Many databases offer tools for improving your search. Make your search in library catalogs and databases more effective by using the following tips:

- Use limiters (often located on the left side of the search results) to further refine your results after searching.

- Change the sort of your results so the order of the articles best fits your needs. Sorting by date allows you to put the most recent or the oldest articles at the top of the results list. Other types of sorts include relevance, alphabetical by author’s name or alphabetical by article title.

- Use the Advanced Search functions of your database to further refine your results or to create more complex combinations of search terms.

- Use the Help section of the database to find more search strategies that apply to that particular database.

Here is an example of using Boolean operators in an Advanced Search:

Figure 7.5.1

Consulting a Reference Librarian

Sifting through library stacks and database search results to find the information you need can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack. Knowing the right keywords can sometimes make all the difference in conducting a successful search. If you are not sure how you should begin your search, or if your search is yielding too many, or too few, results, then you are not alone. Many students find this process challenging, although it does get easier with experience. One way to learn better search strategies is to consult a reference librarian and watch online tutorials that research experts have created to help you. If you have trouble finding sources on a topic, consult a librarian.

Reference librarians are intimately familiar with the systems that libraries use to organize and classify information. They can help you locate a particular book in the library stacks, steer you toward useful reference works, and provide tips on how to use databases and other electronic research tools. Take the time to see what resources you can find on your own, but if you encounter difficulties, ask for help. Many academic librarians are available for online chatting, texting, and emailing as well as face-to-face reference consultations. To make the most of your reference consultation, be prepared to explain, to the librarian, the assignment and your timeline as well as your research questions and ideas for keywords. Because they are familiar with the resources available, librarians may be able to recommend specific resources that fit your needs and tailor your keywords to the search tools you are using.

Exercise 9

At the Library of Congress’s website, search for results on a few terms related to your topic. Review your search results to identify six to eight additional terms you might use when you search for sources using your college library’s catalog and databases.

Exercise 10

Visit your library’s website or consult with a reference librarian to determine which databases would be useful for your research. Depending on your topic, you may rely on a general database, a specialized database for a particular subject area, or both. Identify at least two relevant databases. Conduct a keyword search in these databases to find potentially relevant sources on your topic. Also, search your college’s online library catalog. If the catalog or database you are using provides abstracts of sources, then read them to determine how useful the sources are likely to be. Print out, email to yourself, or save your search results.

Exercise 11

In your list of results, identify three to five sources to review more closely. If the full text is available online, set aside time to open, save, and read it. If not, use the “Find It” tool to see if the source is available through your college’s library. Visit the library to locate any sources you need that are only available in print. If the source is not available directly through your school’s library, then use the library’s online tool to request an interlibrary loan of the source: librarians will send the source in digital form to your email address for you to open and save, or they will send it in print form to your campus library for you to check out.