6.8: Qing Dynasty: Qianlong

- Page ID

- 85852

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

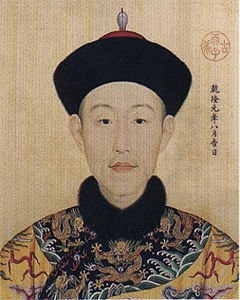

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Qianlong Emperor (乾隆帝) (born Hongli, September 25, 1711 – February 7, 1799) was the fifth emperor of the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and the fourth Qing emperor to rule over China. The fourth son of the Yongzheng Emperor (雍正帝), he reigned officially from October 18, 1735 to February 9, 1796, at which point he abdicated in favor of his son, the Jiaqing Emperor (嘉慶帝 the sixth emperor), in order to fulfill a filial pledge not to reign longer than his grandfather, the illustrious Kangxi Emperor (康熙帝, the second Qing emperor). Despite his retirement, he retained ultimate power until his death in 1799.

Background

Qing Manchu Dynasty

The Manchu Qing ( Ch’ing) dynasty was first established in 1636 by the Manchus to designate their regime in Manchuria and came to power after defeating the Chinese Ming dynasty and taking Beijing in 1644. The first Qing emperor, Shunzhi Emperor (Fu-lin ,reign name, Shun-chih), was put on the throne at the age of five and controlled by his uncle and regent, Dorgon, until Dorgon died in 1650. During the reign of his successor, the Kangxi Emperor (K’ang-hsi emperor; reigned 1661–1722), the last phase of the military conquest of China was completed, and the Inner Asian borders were strengthened against the Mongols. In 1689 a treaty was concluded with Russia at Nerchinsk setting the northern extent of the Manchurian boundary at the Argun River. Over the next 40 years the Dzungar Mongols were defeated, and the empire was extended to include Outer Mongolia, Tibet, Dzungaria, Turkistan, and Nepal.

During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the Qing enacted policies to win the adherence of the Chinese officials and scholars. The civil service examination system and the Confucian curriculum were reinstated. Qing (Ch’ing) emperors learned Chinese, and addressed their subjects using Confucian rhetoric, as their predecessors had. More than half of the important government positions were filled by Manchu and members of the Eight Banners, but gradually large numbers of Han Chinese officials were given power and authority within the Manchu administration. Under the Qing, the Chinese empire trebled its size and the population grew from 150,000,000 to 450,000,000. Many of the non-Chinese minorities within the empire were Sinicized, and an integrated national economy was established.

Early Years

The Qianlong Emperor was born Hongli, September 25, 1711. Certain myths and legends claim that Hongli was actually a Han and not of Manchu descent, others say that he was half Manchu and half Han Chinese. It is apparent from historical records that Hongli was loved both by his grandfather, the Kangxi Emperor and his father, the Yongzheng Emperor. Some historians argue that the Kangxi Emperor appointed Yongzheng as his successor to the throne because of Qianlong, who was his favorite grandson; he felt that Hongli’s mannerisms and character were very similar to his own.

As a teenager, Hongli was skilled at martial arts, and possessed considerable literary ability. After his father’s succession to the throne in 1722, Hongli became the Prince Bao (宝亲王/寶親王). Like many of his uncles, Hongli entered into a battle of succession with his older half-brother Hongshi, who had the support of a large faction of court officials, as well as with Yinsi, the Prince Lian. For many years the Yongzheng Emperor did not endorse the position of Crown Prince, but many speculated that he favored Hongli as his successor. Hongli was sent on inspection trips to the south, and was known to be an able negotiator and enforcer. Hongli was also chosen as chief regent on occasions when his father was away from the capital.

Ascension to the Throne

Even before Yongzheng’s will was read to the assembled court, it was widely known that Hongli would be the new emperor. The young Hongli had been a favorite of his grandfather, Kangxi, and his father, and Yongzheng had entrusted a number of important ritual tasks to him while Hongli was still a prince, and included him in important court discussions of military strategy. Hoping to avoid repetition of the succession crisis that had tainted his own accession to the throne, he had the name of his successor placed in a sealed box secured behind the tablet over the throne in the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing Gong; 乾清宫). The name in the box was to be revealed to other members of the imperial family in the presence of all senior ministers only upon the death of the Emperor. When Yongzheng died suddenly in 1735, the will was taken out and read aloud before the entire Qing Court; Hongli became the 4th Manchu Emperor of China. He took the Reign title of Qianlong (乾隆), meaning strong/heavens (qian); prosperous (long), or put together, the Era of Strong Prosperity.

Frontier Wars

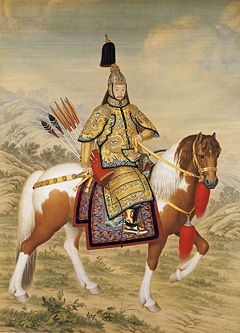

The Qianlong Emperor in Armor on Horseback, by Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766 C.E.).

The Qianlong Emperor was a successful military leader, presiding over a consolidation of the expansive territory controlled by the Qing dynasty. This was made possible not only by Chinese military strength but also by the declining strength and the disunity of the Inner Asian peoples. Under Qianlong, Chinese Turkestan was incorporated into the Qing dynasty’s rule and renamed Xinjiang, while to the West, Ili was conquered and garrisoned. The Qing also dominated Outer Mongolia after inflicting a final defeat on the Western Mongols. Throughout this period there were continued Mongol interventions in Tibet and a reciprocal spread of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia.

Qianlong sent armies into Tibet and firmly established the Dalai Lama as ruler, with a Qing resident and garrison to preserve Chinese suzerainty. Further afield, military campaigns against the Burmese, Nepalese, and Gurkhas forced these peoples to submit and send tribute.

In 1787 the last Le king fled a peasant rebellion in Vietnam and formally requested Chinese aid to restore him to his throne in Thanglong (Hanoi). The Qianlong Emperor agreed and sent a large army into Vietnam to remove the Tay Son peasant rebels who had captured all of Vietnam. The capital, Thanglong, was conquered in 1788, but a few months later, the Chinese army was defeated in a surprise attack during Tet by Nguyen Hue, the second and most capable of the three Tay Son brothers. The Chinese government gave formal protection to the Le emperor and his family but did not intervene in Vietnam for another 90 years.

The Qianlong Emperor’s military expansion captured millions of square miles and brought into the Chinese empire non-Han-Chinese peoples, such as Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kirghiz, Evenks and Mongols, who were potentially hostile. It was also a very expensive undertaking; the funds in the Imperial Treasury were almost depleted due to the military expeditions.

Though the wars were an overall success, they did not bring total victory. The size of the army declined noticeably, and Qing encountered serious difficulties with several enemies. The campaign to dominate the Jin Chuan area lasted three years; the Qing army suffered heavy casualties before Yue Zhongqi finally got the upper hand. A campaign against the Dzungars inflicted heavy losses on both sides.

Artistic Achievements

The Qianlong Emperor was a major patron of the arts. The most significant of his commissions was a catalog of all important works on Chinese culture, the Siku quanshu (四庫全書). Produced in 36,000 volumes, containing about 3,450 complete works and employing as many as 15,000 copyists, the entire work took some twenty years. It preserved many books, but it was also intended as a means of ferreting out and suppressing those deemed offensive to the ruling Manchurians. Some 2,300 works were listed for total suppression and another 350 for partial suppression. The aim was to destroy the writings that were anti-Qing or rebellious, that insulted previous barbarian dynasties, or that dealt with frontier or defense problems.

Qianlong was a prolific poet and a collector of ceramics, an art which flourished in his reign; a substantial part of his collection is in the Percival David Foundation in London.

Architecturally, Qianlong took personal interest in the expansion of the Old Summer Palace and supervised the construction of the Xiyanglou or “Western Mansion.” In the 1750s Qianlong commissioned Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione to design a series of timed waterworks and fountains complete with underground machinery and pipes for the amusement of the Imperial family.

Later Years

In his later years, Qianlong became disillusioned with his power, and began to rely heavily on Heshen, his highest-ranking and most favored minister. The day-to-day governance of the country was left in the hands of Heshen while Qianlong himself indulged in luxuries and his favorite pastime of hunting. It is widely remarked by historians that Heshen laid the foundations for the future collapse and corruption of the Qing dynasty. Eventually it became impossible to reverse the harm that had been done on every level of government. When Heshen was killed, it was discovered that the amount of his personal wealth surpassed the country’s depleted treasury.

Qianlong started his reign in 1735 with about 30,000,000 taels inherited from the period of Yongzheng’s reign. Around 1775, Qianlong reached the peak of the Qing dynasty’s prosperity with about 73,900,000 taels in the treasury, a record unmatched during the reigns of Kangxi or Yongzheng. However, mass corruption on all levels, along with heavy expenses of over 150,200,000 taels on military expeditions, the building of more palaces, six personal trips to Jiangnan, suppression of the White Lotus Rebellion, and luxurious spending, nearly depleted the once-prospering treasury. By the end of Qianlong’s reign in 1796, the treasury was almost empty, leaving a serious problem for his successor, Jiaqing.

The Macartney Embassy

During the mid-eighteenth century, Qianlong began to face severe pressures from the West to increase foreign trade. China’s lack of a Ministry of Foreign Affairs reinforced the belief among Chinese that China was the “central kingdom” of the world. The proposed cultural exchange between the British Empire and the Qing Empire collapsed when Heshen encouraged Qianlong to maintain the belief that the Qing Empire was the center of the world and did not need to pay attention to the British proposal for trade and cultural exchange. The British trade ambassador at the time, George Macartney, was humiliated when he was finally granted an audience with the Qianlong Emperor and arrived to find only an Imperial Edict placed on the Dragon Throne. The edict informed him that the Qing Empire had no need for any goods and services that the British could provide and that the British should recognize that the Qing Empire was far greater than the British Empire. Qianlong’s Edict on Trade with Great Britain referred to Macartney and his embassy as “barbarians,” reflecting the Chinese idea that all countries were “peripheral” in comparison to China.[1]

Insistent demands from Heshen and the Qing Court that the British Trade ambassadors should kneel and kowtow to the empty dragon throne worsened matters. The British rejected these demands and insisted they would kneel only on one knee and bow to the Dragon throne as they did to their own monarch. This caused an uproar. The British trade ambassadors were dismissed and told to leave China immediately. They were informed that the Qing Empire had no particular interest in trading with them, and that strict orders had been given to all local governors not to allow the British to carry out any trade or business in China. [2]

The next year, in 1795, Isaac Titsingh, an emissary from Dutch and Dutch East India Company did not refuse to kowtow; he and his colleagues were treated warmly by the Chinese because of what was construed as their seemly compliance with conventional court etiquette. [3]

Emperor Qian Long’s Letter to George III, 1793

You, O King, live beyond the confines of many seas, nevertheless, impelled by your humble desire to partake of the benefits of our civilization, you have dispatched a mission respectfully bearing your memorial. Your Envoy has crossed the seas and paid his respects at my Court on the anniversary of my birthday. To show your devotion, you have also sent offerings of your country’s produce.

I have perused your memorial: the earnest terms in which it is couched reveal a respectful humility on your part, which is highly praiseworthy. In consideration of the fact that your Ambassador and his deputy have come a long way with your memorial and tribute, I have shown them high favor and have allowed them to be introduced into my presence. To manifest my indulgence, I have entertained them at a banquet and made them numerous gifts. I have also caused presents to be forwarded to the Naval Commander and six hundred of his officers and men, although they did not come to Peking, so that they too may share in my all-embracing kindness.

As to your entreaty to send one of your nationals to be accredited to my Celestial Court and to be in control of your country’s trade with China, this request is contrary to all usage of my dynasty and cannot possibly be entertained. It is true that Europeans, in the service of the dynasty, have been permitted to live at Peking, but they are compelled to adopt Chinese dress, they are strictly confined to their own precincts and are never permitted to return home. You are presumably familiar with our dynastic regulations. Your proposed Envoy to my Court could not be placed in a position similar to that of European officials in Peking who are forbidden to leave China, nor could he, on the other hand, be allowed liberty of movement and the privilege of corresponding with his own country; so that you would gain nothing by his residence in our midst….

If you assert that your reverence for Our Celestial dynasty fills you with a desire to acquire our civilization, our ceremonies and code of laws differ so completely from your own that, even if your Envoy were able to acquire the rudiments of our civilization, you could not possibly transplant our manners and customs to your alien soil. Therefore, however adept the Envoy might become, nothing would be gained thereby.

Swaying the wide world, I have but one aim in view, namely, to maintain a perfect governance and to fulfill the duties of the State: strange and costly objects do not interest me. If I have commanded that the tribute offerings sent by you, O King, are to be accepted, this was solely in consideration for the spirit which prompted you to dispatch them from afar. Our dynasty’s majestic virtue has penetrated unto every country under Heaven, and Kings of all nations have offered their costly tribute by land and sea. As your Ambassador can see for himself, we possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures. This then is my answer to your request to appoint a representative at my Court, a request contrary to our dynastic usage, which would only result in inconvenience to yourself. I have expounded my wishes in detail and have commanded your tribute Envoys to leave in peace on their homeward journey. It behooves you, O King, to respect my sentiments and to display even greater devotion and loyalty in future, so that, by perpetual submission to our Throne, you may secure peace and prosperity for your country hereafter. Besides making gifts (of which I enclose an inventory) to each member of your Mission, I confer upon you, O King, valuable presents in excess of the number usually bestowed on such occasions, including silks and curios-a list of which is likewise enclosed. Do you reverently receive them and take note of my tender goodwill towards you! A special mandate.

From E. Backhouse and J. O. P. Bland, Annals and Memoirs of the Court of Peking. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), 322-331, 1793. [4]

Abdication

In October 1795, after a reign of 60 years, Qianlong officially announced that in the spring of the following year he would voluntarily abdicate his throne and pass the crown to his son. It was said that Qianlong had made a promise during the year of his ascension not to rule longer than his grandfather, the Kangxi Emperor ( 康熙帝 the second Qing emperor). Despite his retirement, however, he retained ultimate power until his death in 1799.

In anticipation of his abdication, Qianlong decided to move out of the Hall of Mental Cultivation in the Forbidden City, the residence dedicated only for the reigning sovereign, and ordered the construction of his residence in another part of the Forbidden City; however, Qianlong never moved out the Hall of Mental Cultivation.

Legends

A legend claims that Qianlong was the son of Chen Yuanlong of Haining. When Emperor Kangxi chose the heir to his throne, he not only considered his son’s ability to govern the Empire, but also the ability and character of his grandson, in order to ensure the Manchus’ everlasting reign over the country. Yongzheng’s own son was a weakling, so he surreptitiously arranged for his daughter to be swapped for Chen Yuanlong’s son, who became the apple of Kangxi’s eye. Thus, Yongzheng succeeded to the throne, and his “son,” Hongli, subsequently became Emperor Qianlong. Later, Qianlong went to the southern part of the country four times, and stayed in Chen’s house in Haining, leaving behind his calligraphy; he also frequently issued imperial decrees making and maintaining Haining as a tax-free state.

Stories about Qianlong visiting the Jiangnan area to conduct inspections disguised as a commoner have been a popular topic for many generations. In total, Qianlong made eight tours of inspection to Jiang Nan; the Kangxi emperor made six inspections.

Family

- Father: The Yong Zheng Emperor (of whom he was the fourth son)

- Mother: Empress Xiao Sheng Xian (1692-1777) of the Niuhuru Clan (Chinese: 孝聖憲皇后; Manchu: Hiyoošungga Enduringge Temgetulehe Hūwanghu)

Consorts

- Empress Xiao Xian Chun

- Demoted Empress Ulanara, the Step Empress of no title

- Empress Xiao Yi Chun

- Imperial Noble Consort Hui Xian

- Imperial Noble Consort Chun Hui

- Imperial Noble Consort Shu Jia

- Imperial Noble Consort Qing Gong

- Imperial Noble Consort Zhe Min

- Noble Consort Ying

- Noble Consort Wan

- Noble Consort Xun

- Noble Consort Xin

- Noble Consort Yu

- Consort Dun

- Consort Shu

- Consort Rong

- Worthy Lady Shun

Children

Sons

- Eldest son: Prince Yong Huang (1728 – 1750), son of Imperial Noble Consort Che Min

- 2nd: Prince Yong Lian [永璉] (1730 – 1738), 1st Crown Prince, son of Empress Xiao Xian Chun

- 5th: Prince Yong Qi [永琪] (1741-1766), bore the title Prince Rong of the blood (榮親王)

- 7th: Prince Yong Zhong [永琮] (1746 – 1748), 2nd Crown Prince, son of Empress Xiao Xian Chun

- 8th: Prince Yong Xuan [永璇], son of the Imperial Noble Consort Shu Jia

- 11th: Prince Yong Xin [永瑆], son of the Imperial Noble Consort Shu Jia

- 12th: Prince Yong Ji, son of the Demoted Empress Ulanara, the Step Empress of no title

- 15th: Prince Yong Yan [永琰] the (Jia Qing Emperor), son of Empress Xiao Yi Chun. In 1789 he was made Prince Jia of the 1st rank (嘉親王).

- 17th: Prince Yong Lin [永璘], given the title as the 1st Prince Qing Yong Lin. His grandson is Prince Yi Kuang, bore the title Prince Qing [慶親王奕劻] (February 1836 – January 1918).

- 18th: Prince ?

Daughters

- 1st: Princess ? (1728 – 1729), daughter of Empress Xiao Xian Chun

- 3rd: Princess He Jing [固倫和敬公主] (1731 – 1792), daughter of Empress Xiao Xian Chun

- 4th: Princess He Jia [和硕和嘉公主] (1745 – 1767), daughter of the Imperial Noble Consort Chun Hui

- 5th: Princess ?, daughter of the Demoted Empress Ulanara, the Step Empress of no title

- 7th: Princess He Jing [固伦和静公主] (1756 – 1775), daughter of Empress Xiao Yi Chun

- 10th: Princess He Xiao (daughter-in-law of He Shen) was spared execution when the Jia Qing Emperor prosecuted Heshen in 1799. She was given some of He Shen’s estate.

See also

- Jean Joseph Marie Amiot

- Giuseppe Castiglione

- Manwen Laodang

- Canton System

- Xi Yang Lou

- Long Corridor

- Qianlong Empire. Authored by: New World Encyclopedia. Located at: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Qianlong_Emperor. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Budala 5. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Budala5.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Qianlong Emperor in Ceremonial Armor on Horseback. Authored by: Giuseppe Castiglione. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Qianlong_Emperor_in_Ceremonial_Armour_on_Horseback.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Qianlong 1. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Qianlong1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Qianlong coin. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Qianlongcoin.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Emperor Qianlong reading. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Emperor_Qianlong_reading.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Portrait of the Qianlong Emperor in Court Dress. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_the_Qianlong_Emperor_in_Court_Dress.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright