3.3: Biography: Howard Zinn

- Page ID

- 86572

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

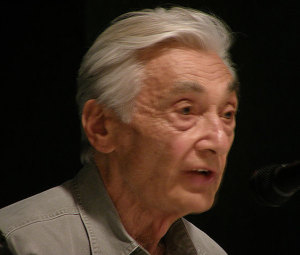

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922 – January 27, 2010) was an American historian, author, playwright, and social activist. He was a political science professor at Boston University. Zinn wrote more than 20 books, including his best-selling and influential A People’s History of the United States.

Zinn described himself as “something of an anarchist, something of asocialist. Maybe a democratic socialist.” He wrote extensively about the civil rights and anti-war movements, and labor history of the United States. His memoir, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, was also the title of a 2004 documentary about Zinn’s life and work.

Life and career

World War II

Eager to fight fascism, Zinn joined the U.S. Army Air Force during World War II and was assigned as a bombardierin the 490th Bombardment Group, bombing targets in Berlin, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. As bombardier, Zinn dropped napalm bombs in April 1945 on Royan, a seaside resort in southwestern France. The anti-war stance Zinn developed later was informed, in part, by his experiences.

On a post-doctoral research mission nine years later, Zinn visited the resort near Bordeaux where he interviewed residents, reviewed municipal documents, and read wartime newspaper clippings at the local library. In 1966, Zinn returned to Royan after which he gave his fullest account of that research in his book, The Politics of History. On the ground, Zinn learned that the aerial bombing attacks in which he participated had killed more than 1000 French civilians as well as some German soldiers hiding near Royan to await the war’s end, events that are described “in all accounts” he found as “une tragique erreur” that leveled a small but ancient city and “its population that was, at least officially, friend, not foe.” In The Politics of History, Zinn described how the bombing was ordered—three weeks before the war in Europe ended—by military officials who were, in part, motivated more by the desire for their own career advancement than in legitimate military objectives. He quotes the official history of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ brief reference to the Eighth Air Force attack on Royan and also, in the same chapter, to the bombing of Pilsen in what was then Czechoslovakia. The official history stated that the famous Skoda works in Pilsen “received 500 well-placed tons,” and that “because of a warning sent out ahead of time the workers were able to escape, except for five persons.”

Zinn wrote:

I recalled flying on that mission, too, as deputy lead bombardier, and that we did not aim specifically at the ‘Skoda works’ (which I would have noted, because it was the one target in Czechoslovakia I had read about) but dropped our bombs, without much precision, on the city of Pilsen. Two Czech citizens who lived in Pilsen at the time told me, recently, that several hundred people were killed in that raid (that is, Czechs)—not five.

Zinn said his experience as a wartime bombardier, combined with his research into the reasons for, and effects of the bombing of Royan and Pilsen, sensitized him to the ethical dilemmas faced by G.I.s during wartime. Zinn questioned the justifications for military operations that inflicted massive civilian casualties during the Allied bombing of cities such as Dresden, Royan, Tokyo, and Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II, Hanoi during the War in Vietnam, and Baghdad during the war in Iraq and the civilian casualties during bombings in Afghanistan during the current war there. In his pamphlet, Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence written in 1995, he laid out the case against targeting civilians with aerial bombing.

Six years later, he wrote:

Recall that in the midst of the Gulf War, the U.S. military bombed an air raid shelter, killing 400 to 500 men, women, and children who were huddled to escape bombs. The claim was that it was a military target, housing a communications center, but reporters going through the ruins immediately afterward said there was no sign of anything like that. I suggest that the history of bombing—and no one has bombed more than this nation—is a history of endless atrocities, all calmly explained by deceptive and deadly language like ‘accident’, ‘military target’, and ‘collateral damage’.

Education

After World War II, Zinn attended New York University on the GI Bill, graduating with a B.A. in 1951. At Columbia University, he earned an M.A. (1952) and a Ph.D. in history with a minor in political science (1958). His masters’ thesis examined the Colorado coal strikes of 1914. His doctoral dissertation LaGuardia in Congress was a study of Fiorello LaGuardia’s congressional career, and it depicted “the conscience of the twenties” as LaGuardia fought for public power, the right to strike, and the redistribution of wealth by taxation. “His specific legislative program,” Zinn wrote, “was an astonishingly accurate preview of the New Deal.” It was published by the Cornell UniversityPress for the American Historical Association. LaGuardia in Congress was nominated for the American Historical Association’s Beveridge Prize as the best English-language book on American history.

His professors at Columbia included Harry Carman, Henry Steele Commager, and David Donald. But it was Columbia historian Richard Hofstadter’s The American Political Tradition that made the most lasting impression. Zinn regularly included it in his lists of recommended readings, and, after Barack Obama was elected President of the United States, Zinn wrote, “If Richard Hofstadter were adding to his book The American Political Tradition, in which he found both ‘conservative’ and ‘liberal’ presidents, both Democrats and Republicans, maintaining for dear life the two critical characteristics of the American system, nationalism and capitalism, Obama would fit the pattern.”

In 1960–61, Zinn was a post-doctoral fellow in East Asian Studies at Harvard University.

Academic career

“We were not born critical of existing society. There was a moment in our lives (or a month, or a year) when certain facts appeared before us, startled us, and then caused us to question beliefs that were strongly fixed in our consciousness – embedded there by years of family prejudices, orthodox schooling, imbibing of newspapers, radio, and television. This would seem to lead to a simple conclusion: that we all have an enormous responsibility to bring to the attention of others information they do not have, which has the potential of causing them to rethink long-held ideas.”

Zinn was professor of history at Spelman College in Atlanta from 1956 to 1963, and visiting professor at both the University of Paris andUniversity of Bologna. At the end of the academic year in 1963, Zinn was fired from Spelman. In 1964, he accepted a position at Boston University, after writing two books and participating in the Civil Rights Movement in the South. His classes in civil liberties were among the most popular at the university with as many as 400 students subscribing each semester to the non-required class. A professor ofpolitical science, he taught at BU for 24 years and retired in 1988 at age 64.

“He had a deep sense of fairness and justice for the underdog. But he always kept his sense of humor. He was a happy warrior,” said Caryl Rivers, journalism professor at Boston University. Rivers and Zinn were among a group of faculty members who in 1979 defended the right of the school’s clerical workers to strike and were threatened with dismissal after refusing to cross a picket line.

Zinn came to believe that the point of view expressed in traditional history books was often limited. BiographerMartin Duberman noted that when he was asked directly if he was a Marxist, Zinn replied, “Yes, I’m something of a Marxist.” He especially was influenced by the liberating vision of the young Marx in overcoming alienation, and disliked Marx’s later dogmatism. In later life he moved more toward anarchism.

He wrote a history textbook, A People’s History of the United States, to provide other perspectives on American history. The textbook depicts the struggles of Native Americans against European and U.S. conquest and expansion, slaves against slavery, unionists and other workers against capitalists, women against patriarchy, and African-Americans for civil rights. The book was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1981.

In the years since the first edition of A People’s History was published in 1980, it has been used as an alternative to standard textbooks in many high school and college history courses, and it is one of the most widely known examples of critical pedagogy. The New York Times Book Review stated in 2006 that the book “routinely sells more than 100,000 copies a year”.

In 2004, Zinn published Voices of a People’s History of the United States with Anthony Arnove. Voices is a sourcebook of speeches, articles, essays, poetry and song lyrics by the people themselves whose stories are told in A People’s History.

In 2008, the Zinn Education Project was launched to support educators using A People’s History of the United States as a source for middle and high school history. The Project was started when a former student of Zinn, who wanted to bring Zinn’s lessons to students around the country, provided the financial backing to allow two other organizations, Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change to coordinate the Project. The Project hosts a website that has over 100 free downloadable lesson plans to complement A People’s History of the United States.

The People Speak, released in 2010, is a documentary movie based on A People’s History of the United States and inspired by the lives of ordinary people who fought back against oppressive conditions over the course of the history of the United States. The film, narrated by Zinn, includes performances by Matt Damon, Morgan Freeman, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Eddie Vedder, Viggo Mortensen, Josh Brolin, Danny Glover, Marisa Tomei, Don Cheadle, and Sandra Oh.

Civil Rights Movement

From 1956 through 1963, Zinn chaired the Department of History and social sciences at Spelman College. He participated in the Civil Rights Movement and lobbied with historian August Meier “to end the practice of theSouthern Historical Association of holding meetings at segregated hotels”.

While at Spelman, Zinn served as an adviser to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and wrote about sit-ins and other actions by SNCC for The Nation and Harper’s.In 1964, Beacon Press published his book SNCC: The New Abolitionists.

Zinn collaborated with historian Staughton Lynd mentoring student activists, among them Alice Walker, who would later write The Color Purple; and Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president of the Children’s Defense Fund. Edelman identified Zinn as a major influence in her life and, in that same journal article, tells of his accompanying students to a sit-in at the segregated white section of the Georgia state legislature. Zinn also co-wrote a column in The Boston Globe with fellow activist Eric Mann, “Left Field Stands”.

Although Zinn was a tenured professor, he was dismissed in June 1963 after siding with students in the struggle against segregation. As Zinn described in The Nation, though Spelman administrators prided themselves for turning out refined “young ladies,” its students were likely to be found on the picket line, or in jail for participating in the greater effort to break down segregation in public places in Atlanta. Zinn’s years at Spelman are recounted in his autobiography You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times. His seven years at Spelman College, Zinn said, “are probably the most interesting, exciting, most educational years for me. I learned more from my students than my students learned from me.”

While living in Georgia, Zinn wrote that he observed 30 violations of the First and Fourteenth amendments to theUnited States Constitution in Albany, Georgia, including the rights to freedom of speech, freedom of assembly andequal protection under the law. In an article on the civil rights movement in Albany, Zinn described the people who participated in the Freedom Rides to end segregation, and the reluctance of President John F. Kennedy to enforce the law. Zinn has also pointed out that the Justice Department under Robert F. Kennedy and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, headed by J. Edgar Hoover, did little or nothing to stop the segregationists from brutalizing civil rights workers.

Zinn wrote about the struggle for civil rights, as both participant and historian. His second book, The Southern Mystique was published in 1964, the same year as his SNCC: The New Abolitionists in which he describes how the sit-ins against segregation were initiated by students and, in that sense, were independent of the efforts of the older, more established civil rights organizations.

In 2005, forty-one years after his firing, Zinn returned to Spelman where he was given an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters. He delivered the commencement address[44] titled, “Against Discouragement” and said that “the lesson of that history is that you must not despair, that if you are right, and you persist, things will change. The government may try to deceive the people, and the newspapers and television may do the same, but the truth has a way of coming out. The truth has a power greater than a hundred lies.”

Anti-war efforts

Zinn wrote one of the earliest books calling for the U.S. withdrawal from its war in Vietnam. Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal was published by Beacon Press in 1967 based on his articles in Commonweal, The Nation, andRamparts.

In Noam Chomsky’s view, The Logic of Withdrawal was Zinn’s most important book. “He was the first person to say—loudly, publicly, very persuasively—that this simply has to stop; we should get out, period, no conditions; we have no right to be there; it’s an act of aggression; pull out. It was so surprising at the time that there wasn’t even a review of the book. In fact, he asked me if I would review it in Ramparts just so that people would know about the book.”

In December 1969, radical historians tried unsuccessfully to persuade the American Historical Association to pass an anti-Vietnam War resolution. “A debacle unfolded as Harvard historian (and AHA president in 1968) John Fairbank literally wrestled the microphone from Zinn’s hands.” Correspondence by Fairbank, Zinn and other historians, published by the AHA in 1970, is online in what Fairbank called “our briefly-famous Struggle for the Mike.”

In later years, Zinn was an adviser to the Disarm Education Fund.

- Howard Zinn. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Howard_Zinn. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Image of Howard Zinn. Authored by: User B-Fest of Athens indymedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Howard_Zinn_at_B-Fest_2009_II.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike