11: History of Photography

- Page ID

- 92245

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)To appreciate a medium such as photography, knowing a little bit about where it came from is essential. It is no different than the appreciation of a friend in this regard. Don’t you want to know what their life has been like thus far? This chapter is a very brief history of the beginnings of photography.

To make photographs, two things are needed: a camera and a way to make the images it projects permanent. The first of these requirements has been around for hundreds of years in the form of a camera obscura. This is a camera an artist could use to manually trace the projected image. In Latin, camera means room and obscura means dark. Makes sense.

Photography (light writing in Greek) had to wait for a means to automatically secure the camera obscura image. It was known that silver compounds were sensitive to light, but getting them to form an image that wouldn’t go away when you looked at it under light was impossible.

Instead of silver, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce experimented with securing images using an asphalt that hardened with light. Although he did get images using this method, it was not a practical process—the images were faint and the exposure times, even in bright sun-light, were all day long. Niépce’s process was a dead end, and the invention of photography would have to wait for a better way of making automatic images.

So, why mention him at all? First, an example of his process is the oldest photograph that still exists—taken over a decade before photography was invented. Secondly, his experiments sparked the interest of someone who would actually go on to invent a practical method for making photographs.

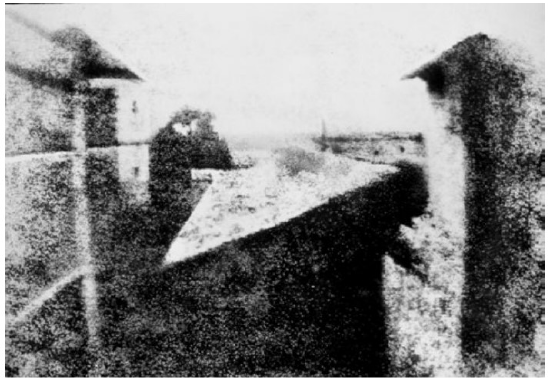

|

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, 1826. View from his window (original is much lower contrast). |

|

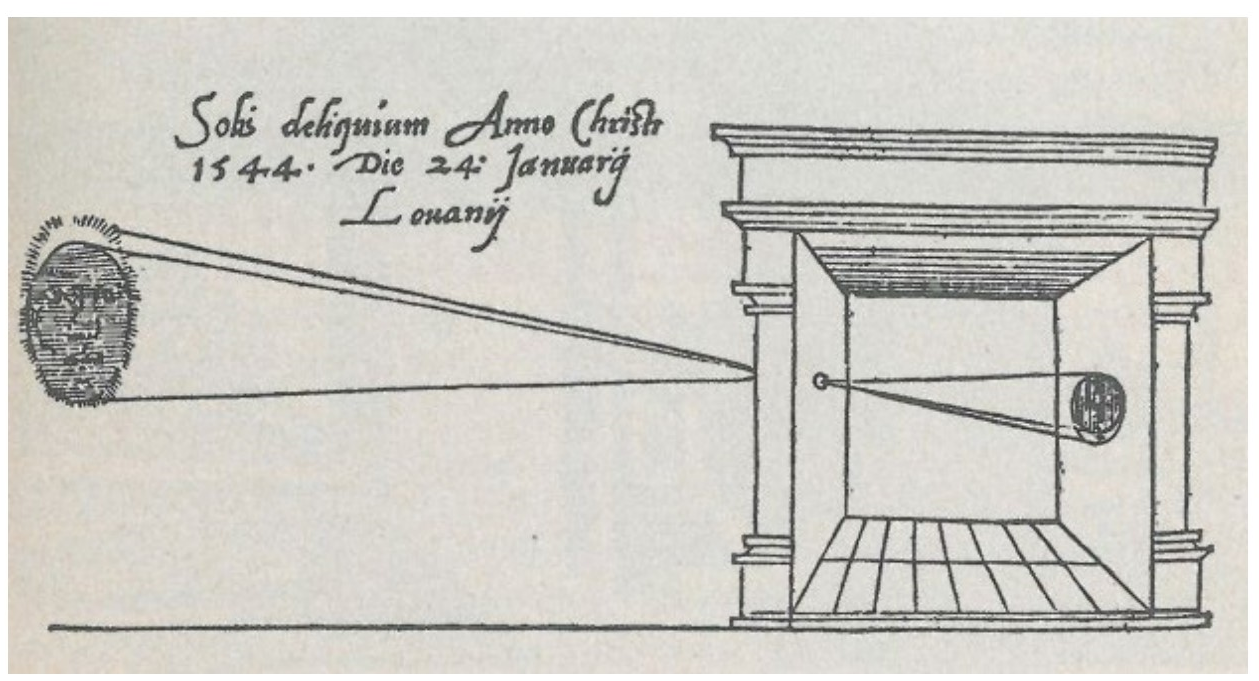

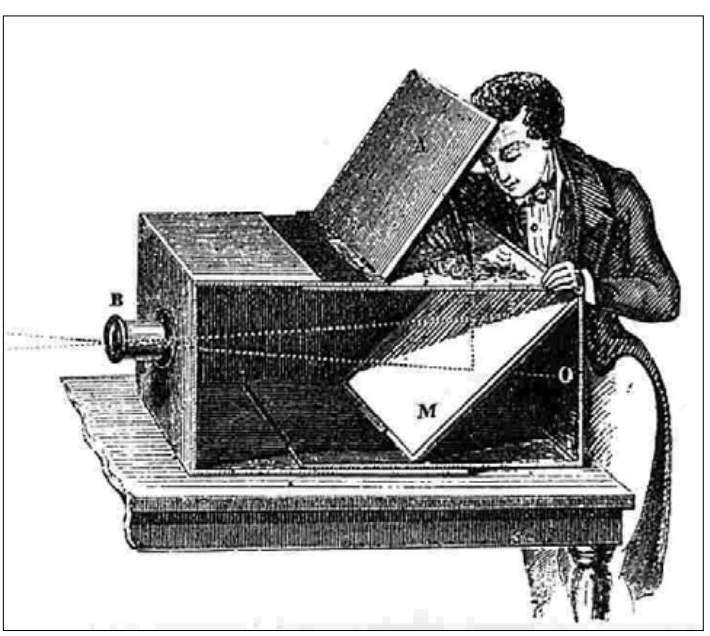

ABOVE Description of a camera obscura from 1544 BELOW Eighteenth Century camera obscura being used to trace an image. Light enters the lens and the image is reflected up by a mirror to project onto a piece of translucent glass.

|

Daguerreotype

Louis Daguerre was an entertainer of sorts—he owned buildings, called dioramas, where people could view huge paintings of romantic (in the awe-inspiring sense) far-away places. These canvases were painted on both sides so that by changing louvers in the ceiling the scenes could appear to go from day to night.

Diorama paintings were expensive since realistic detail was needed to transport the audience into another time and place. So Daguerre contacted his fellow Frenchman Niépce to inquire about his process of automatically making images.

Somehow or other (the exact way is speculation), Daguerre came up with a process radically different than Niépce’s. They both used metal plates, but Daguerre’s were plated with silver, then sensitized with an acid that made the silver on the surface a silver compound. After an exposure in a camera obscura, the plate was then set over boiling mercury (no, that is not good for you) to make the image more visible.

|

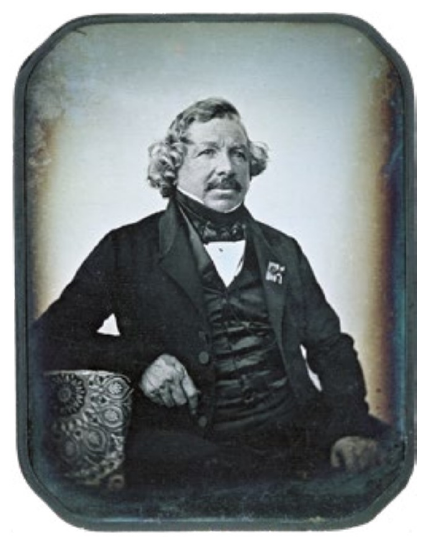

RIGHT Daguerreotype of Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre taken by Jean-Baptiste Sabatier-Blot. They liked long names. BELOW Daguerre’s 1838 image of Boulevard du Temple. This is a busy street, but the exposure was too long to capture anyone but a shoe-shiner and his customer (lower left).

|

Daguerre sold his invention to the French government, who announced the Daguerreotype process free to the world (no patents) in 1839. Perhaps governments could do that today with important inventions...

Daguerre’s 1839 invention of photography was not perfect. The silver plate that was in the camera was the one you took home with you, so to make a copy another photograph had to be made. Although improved later, the first Daguerreotypes required very long exposures and they were difficult to make, and therefore expensive, especially if they were large (bigger than an old flip-phone screen). Since the image could be wiped away with a thumb, they had to be put in cases and covered with glass. And they were so reflective that often you had to hold the lid of the case in the right position to see the image.

|

RIGHT Daguerreotype in case. BELOW The image reverses if the reflective surface of the image is reflecting lighter tones.

|

Hatters and PhotographersThe mad hatter of Alice in Wonderland was not the only hatter who was mad—hat makers used mercury in the felting. Photographers also used mercury, boiling it under their noses. It is a sad irony that many photographers became victims of mercury poisoning which not only crippled their minds and killed them, but also sometimes blinded them. |

Even with their shortcomings, Daguerreotypes were extremely popular across the world, and you can still sometimes find them in antique markets. With photographs being so ubiquitous now, it is difficult to imagine how important Daguerreotypes were. To be able to hold an image of someone or something. Not the interpretation of a painter, but an actual reflection. The immediacy of this is still amazing. Look at a photograph of someone who has died, and there they are, getting a photograph made of themselves, looking out at the camera... but they are dead (this observation is from the book Camera Lucida by the philosopher Roland Barthes).

The Daguerreotype was a disrupting technology. Portrait painters worried that it would put them out of business, and for ones that specialized in inexpensive small likenesses, it did. But photography was unsatisfying in ways—a common complaint by someone having their photograph taken was that the result was far uglier than they were.

As with all new technologies, there was confusion as to what photography was and how it should be used. Many emulated painting—after all, the product was an image. But a nude photographed elicits a different reaction than a nude painted. It was like art, but there was no hand involved, so was it art?

The uses and purposes of photography unfolded over time, and as the technology of the Daguerreotype improved (shorter exposures, more controlled image quality), so did the ability of photographers to find the strengths of the medium.

Henry & HippolyteWhen Daguerre’s discovery was announced, others claimed that they too had invented photography. Hippolyte Bayard in France and Henry Fox Talbot in Britain invented photographic processes so unlike Daguerre’s that the differences serve as proof that they too had indeed invented photography. Bayard’s process used a silver compound (halide is a more precise term) embedded in paper to put into the camera. Talbot’s process also used this method, but in his invention the paper produced a negative image. This negative image was then laid over another sheet of sensitive paper and exposed to make a positive image. So many prints could be made. Talbot’s process was patented. It produced somewhat fuzzy results, but wonderful images were made with it. His negative/positive approach foreshadowed later processes where many copies can be made from the original negative. |

|

Robert Cornelius, 1839. This Daguerreotype self portrait may be the earliest example of portrait photography surviving. And the earliest ‘selfy’. |

Southworth & Hawes was a Boston photography firm that produced outstanding Daguerreotypes. Although they excelled at beautifully sensitive portraiture, they also photographed other scenes, such as an early operation using ether as anesthesia (at right). Photography was not the only invention that changed life at the time. Asleep under ether was a much better alternative to alcohol, opiates, and straps (although one could wish for those surgeons to wash their hands). The utilization of steam railroads was an almost magical alternative to the horse and wagon. It was a time of change.

Collodion

Ether was not only good for putting patients asleep —it was also used in forming a new type of surgical dressing. Gun cotton, a syrupy substance also called collodion, could be painted on wounds to seal them or hold down bandages. It is still sometimes used for this today.

In 1851 Frederick Scott Archer found that silver compounds could be mixed with collodion to make them stick to glass. This coated glass was put into a camera, exposed, then developed (bathed in chemicals to make the image appear). The resulting negative (tones were reversed) was then laid over sensitized paper to form a positive image. The collodion process is also called wetplate since the glass had to be coated, then exposed and developed before the collodion mixture dried.

|

Albert Southworth and Josiah Hawes, 1847 |

Over time the collodion process completely replaced the Daguerreotype. It was easier, cheaper, and the print size was only limited to the camera size the glass plates would fit into. Also, very importantly, multiple prints could be made from one negative, solving a major shortcoming of the Daguerreotype.

For over thirty years collodion was how photography was defined. It is probable that you or your family have photographs taken with this process. The paper prints used egg whites instead of collodion to bind the silver to the paper. These albumin prints can be identified by their cheesy hue and fading. The thin prints are always mounted on a card or board.

There are two variants of the collodion process. The first is the tintype, where a direct positive was made in the camera on a black piece of metal coated with collodion.

Although these could not have multiple copies (since there was no negative), they could be made very cheaply, were durable, and many survive in excellent condition.

The collodion could also be coated on glass to make a direct positive called an ambrotype. These are often in cases like Daguerreotypes, but they do not have the mirror finish.

|

LEFT Anonymous cheese-colored albumin print. Originally the print was probably tonally rich with a purplish hue. RIGHT Anonymous tintype. Notice the hand coloring of the cheeks. This hand coloring is also found in many Daguerreotypes (such as the one at the beginning of this chapter). |

By the 1870s the collodion process was improved to the point that it was possible to develop the negatives after the collodion had dried in some situations, meaning photographers did not have always have to lug a darkroom around with them, but could process the image at their leisure.

Collodion changed photography from a craft in which skilled technicians produced expensive one-of-a-kind photographs to a medium that was accessible to many. Although it was still too difficult for most lay-persons to make collodion photographs, it democratized the medium enough that everyone on this side of poverty could have their own photographs of themselves, their loved ones, and famous people.

The collodion process also enabled photographers for the first time to bring images of many different aspects of life to a large audience.

War Photography

Even though he took few photographs of the United States Civil War, Matthew Brady is responsible for most images of the conflict. Here is how that works: Brady was a highly successful owner of photography studios with locations in multiple cities, taking photographs of the rich and famous. The source for that portrait of Abraham Lincoln on the five dollar bill and the penny? —Brady.

|

TOP Alexander Gardner, 1862. Bodies on the battlefield at Antietam. RIGHT Matthew Brady in 1875.

|

When the Civil War began, Brady saw it not only as his duty, but also as a business investment, to photograph this momentous occasion. He invested all of his fortune into hiring photographers to document the war as truthfully as they could. These photographers, including Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, could not take photographs of action (exposure times were measured in seconds), but they provided thousands of images which showed the conflict in unflinching terms. Today the surviving images form our view of what that war was like.

After the war, Brady’s photographers went on to other things, as did the public. No one wanted to remember that horrible chapter in American history. Eventually the government did buy some of Brady’s negatives, but it was too little and too late. Brady never got out of debt, and he died in a charity ward.

Travel Photography

After the war, one of Brady’s photographers, Timothy O’Sullivan, traveled west with a government expedition. Distant places in the 19th Century were much less accessible than they are today, and most people only knew of the American West, the Middle East, and the Egyptian pyramids through written descriptions and unverifiable drawings.

|

Timothy O’Sullivan, 1873. White House ruins at Canyon de Chelly, Arizona. |

Photography changed that, and O’Sullivan was one of many who brought proof of these places back home. Photographs could not be mass reproduced in publications at the time, but the published engravings were careful to note that they were drawn from photographs. Photographs themselves were mass printed for sale as portfolios (for the well-heeled) and as stereo (3D) cards for the middle class. A hand-held stereo viewer was must-have entertainment in a Victorian parlor.

Amateurs and Artists

Although photography was rarely put on the same plane as painting and sculpture in the Nineteenth Century, there were many photographers using it as an expressive medium.

|

Julia Margaret Cameron, 1864. The title of this image is Sadness. The model is the actress Ellen Terry. |

Julia Margret Cameron was one of these photographers. To call her an amateur is somewhat misleading in today’s terms. Before the Twentieth Century amateur did not have the negative connotations it has today. Indeed it was amateurs —people with incomes separate from their pursuits —who made many important contributions to science and art.

Cameron is sometimes derided as ‘not very good at technique’, but her technique fit her vision very well. Her photographs are straightforward and insightful. Because allegory (bigger truths revealed by symbolism) was seen as high art, many of Cameron’s image titles are cringe-worthy today. But the portraits themselves are timeless.

O. G. Rejlander was a photographer who exhibited his work alongside paintings in exhibitions. His allegorical work was celebrated in part because he strove to over-come the prejudices of photography as a handless craft by highly manipulating the images. Despite the nudity in the photograph at right, a copy of it was bought by Queen Victoria for her husband. It is said that the left half was covered by a curtain when it was publicly displayed.

Rejlander was part of an informal circle of famous artists, writers, and scientists who all knew each other. The author Lewis Carroll (Charles Dodgson) was also part of that circle and was inspired to take up photography by Rejlander. The Alice of Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland was Alice Liddell, a favorite friend of Dodgson’s whom he photographed many times.

Scientific Photography

In 1872 Rejlander illustrated Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions of Man and Animals with his photographs. Photography was involved with the sciences both to illustrate and to inquire. One famous experiment sounds a little strange today, but is as interesting as it is important to the history of photography...

The question had to do with how a horse uses its legs at different gaits. Often paintings depicted horses running with all hooves off of the ground—front legs directly in front, back legs directly in back. But did they really run like that? It is impossible to tell by just observing them since those legs move so darned fast.

|

O. G. Rejlander, 1857. The Two Ways of Life was an allegory with a moral purpose. Combining 35 separate images, Rejlander depicts how a young man can go into a world of sin represented by the groups of figures on the left. Instead, the young man can proceed into a life of virtue represented by the figures on the right. |

Edward Muybridge was a photographer mostly known for his landscapes of the American West, but he was also an inventor who was capable of pushing the limits of photography and the camera. Because of this, he was hired to settle a dispute over the running style of horses.

Muybridge set up 12 cameras along a track. With each camera, a thread strung across the track tripped the shutter. The result was proof of the running style of a horse. But it turned out to be more. Muybridge noticed that if you saw each image quickly in succession, the horse appeared to be moving. Muybridge’s device for viewing the images in this way is a zoopraxiscope. Although not practical except as a curiosity, this was part of the beginnings of motion pictures.

Muybridge continued to do motion studies with both human and animal models. These studies were used by scientists and artists to understand how humans and animals move.

Really?If you like undeserved rumor, intrigue, and titillation with your photography, read more about Lewis Carroll and Edward Muybridge. |

|

Edward Muybridge, 1878. Because exposure times would have been too slow otherwise, the photographs are underexposed to the point that only the silhouette of the horse is discernible. |

Socially Responsible Photography

Towards the end of the Nineteenth Century the plight of others became a concern. Everything from disappearing native societies to child labor was photographed and introduced into evidence that demanded action and sometimes changed laws.

Jacob Riis photographed the plight of the poor in New York City. As a police reporter in the slums, he knew them well, and was determined to help those who lived in poverty. He used his photographs of the poor first in a series of lectures he gave, then in books, the most famous being How the Other Half Lives.

It is hard to overestimate the influence of Riis and his photographs. Not only in his own city, but in other cities that saw themselves mirrored in his reportage. Using photographs to reveal the hardships of others was later done by the US government to document living conditions during the Depression. Photography is still a powerful force for change today.

|

Jacob Riis, 1888. Lodgers in a crowded Bayard Street tenement. |

Portraiture

Of all of the uses of photography in the Nineteenth Century, portraiture is paramount. Humans love pictures of themselves and of other humans. Its just the way it is. Oh, and cats too nowadays.

The most popular form that collodion portraits took were small cards upon which the portraits were mounted. These were called cartes de visite, which translated from French is visiting cards. Often visitors would leave a calling card (like today’s business card) when they visited. Cartes de visite were the photographic equivalent. Although not important as calling cards, they were the primary way to have a photograph of someone. Like a class picture in school. Trade them, collect them, put them in albums. These were inexpensive enough for any amount of disposable income, and you could come out of the photographer’s studio with several versions. Very much like today’s portraits.

Also called card photographs, these cartes de visite are plentiful leftovers from more than a century ago, and can be readily found in drawers, attics, and flea markets. If you happen to find a family album with someone famous or infamous in it, don’t get too excited or alarmed. Your great-grandfather probably didn’t know the queen, but could buy a carte de visite of her for a few pennies.

Later card photographs are a little bigger than cartes de visite, and are called cabinet photographs.

|

LEFT Front and back of typical carte de visite. These were not high art, but cheap keepsakes. ABOVE Carte de visite of Sojourner Truth. Copies of these were sold to raise money (see caption). This was at a time when photographic reproduction in publications was not technically possible. |

Gelatin

Besides making Jello-like desserts, it was found that gelatin made a very good alternative to collodion in photography. By the late 1870s photographers could buy their plates (the glass with the light sensitive coating) ready-made. This was surely an improvement, but an incremental one.

The real breakthrough in photography was in 1888, when a plate manufacturer, George Eastman, bought a Wisconsin farmer’s patents and came out with a totally new way of taking photographs. He coated a long strip of paper with the gelatin and silver mixture, then rolled it up and put it in a very simple camera with a fixed shutter speed, aperture, and focus.

All the photographer had to do was aim the camera in the general direction of the subject, then push the button. A lot like a cellphone camera.

After a hundred photographs filled the roll of film, the photographer sent the camera back to Kodak, the name of Eastman’s new company. Kodak would then send the photographs back as prints and the camera reloaded with a new roll of film ready to shoot more images.

With a Kodak camera anyone could be a photographer and the snapshot was born. People started grinning for the camera, and casual parts of life were recorded. It was a new way of looking at the world.

Photographic processes changed rapidly around the turn of the century. The paper backing Eastman used was replaced by a type of clear flexible film. Gelatin, which had many advantages over albumen as well as collodion, also became the common print emulsion (the mixture which holds the silver in suspension). These prints retain their tonality much better over time and are more neutral in color.

|

Early gelatin snapshot. A woman with a dog, three cats and a bird in a wheelbarrow (you wouldn’t smile much either). At the bottom right you can see a reflection from silvering, a common sign of aging with gelatin prints, especially earlier ones. |

Twentieth Century

Excuse the brevity, but actually the entire Twentieth Century was a bit of a watershed in the technique of photography. Cameras became more precise and generally smaller over time with more automation towards the end of the century. Kodak, with its impressive start, dominated the market of photography supplies. Film became somewhat more sensitive to light, and instant photographs became an option in the late 1940s with Edwin Land’s invention of the Polaroid camera.

Color photography, which had been around since the 1860s, became practical, and then more practical, and by the 1950s and 1960s becomes the norm. Movies progressed as well, quickly gaining sound and then color.

All of this is not to say that photography stood still aesthetically or conceptually in the 20th Century. As a matter of fact, that evolution is far more interesting but beyond the limits of this text as there is no concise story. Find the story yourself. You have names and places to start with in the sections of this text dealing with photographers. It is a rich subject with many curves and surprises as it weaves around other media.

|

Images from an Apple QuickTake 100 camera (1994). The downsides of the camera were that the images were of poor quality (and 0.3 megapixel), the camera could only take 8 images before an excruciatingly long download to the computer, and the price was $750. The upside was that it was a digital camera. |

Twenty-First Century

Digital photography has been around since 1975 and perhaps even before (depending on how you define digital). The first digital camera as we know it today was available in 1990, and what many recognize as the first digital consumer camera was offered by Apple in 1994.

But it was around the turn of the century when digital technology became an inexpensive alternative to film. Kodak, which had a great run for over a hundred years, filed for bankruptcy in 2012. This signaled the relegation of film photography to an archaic process. One that still has uses, but is not the mainstream technology of photography.

This brings us to today, when virtually all photography is done digitally. The cellphone has replaced the Kodak, and digital cameras have replaced the 35mm camera. The use of photographs has grown into a part of daily communication.

History Questions

Which came first: the camera obscura or photography?

Who invented photography?

When was photography invented (approximately)?

What photographic process produces very reflective images?

What photographic process replaced the Daguerreotype?

What is the collodion process also called?

What print process used egg whites?

Who is responsible for many Civil War photographs?

What famous book author was also a very good amateur photographer?

What photographer was instrumental in developing motion pictures?

Who used photographs to show how the poor lived?

What is a common 19th Century photograph mounted on a card called?

What substance replaced collodion in the late 19th Century?

Who started the Kodak Company?

What company dominated photographic supplies during the 20th Century?