0: Introduction

- Page ID

- 90426

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Why do you need this book?

Let’s make this simple. If you just want to take photographs, follow these steps:

1. Open the camera on your phone.

2. *Wipe the front of the lens with your shirt.

3. Aim in the general direction of what you want to photograph.

4. Take the photograph.

5. Post the photograph somewhere.

That is it. That is all. No more to it. Skip to the end of this book —you are done.

Well, actually (you guessed it) we are not done, because I am assuming you are using this book because you want better photographs than this technique will give you, either out of interest or if you want to pass a photography class.

Cellphone cameras

There is nothing wrong with cellphone cameras. The evolution of them has been amazing, and at this point, under the certain conditions and for certain uses, they can take just as good a photograph as any camera can. And they can do things dedicated cameras cannot, such as produce instant GIFs and slow motion movies.

*I just taught you make your cellphone photographs better.

Why and HowSome excellent students I have worked with are much better at memorizing things than understanding how they work. If you are like these students, my apologies. This book is about the why of things. Photography is not a pursuit that is learned by memorization. |

However, a cellphone camera doesn’t have the control that a dedicated camera has, and control is what you should be after in using this book. In other words, with a cellphone camera you cannot pick focus and non-focus areas, adjust the amount of motion blur, adjust angle of view without losing quality, control perspective, shoot into the sun or use other difficult lighting effectively, use external flash, adjust the sensitivity of the sensor... the list goes on.

Also, the images that result from cellphone cameras are not able to be edited effectively, as they have weak tonality and color fidelity. You have very little control over how parts of the image are interpreted. Nor are they able to be cropped into a detail or enlarged successfully. Basically, you have very little control in either the shooting or the processing of the image.

This could change, and engineers are working hard at overcoming these limitations. But their objective is not giving more control, but instead producing a more pleasing image. The objective of this book is not more pleasing images, but instead more control. If cellphone cameras do allow more control in the future, the contents of this book will not be outdated, but instead they will also be relevant to cellphone cameras as well as other cameras.

So, you use a cellphone camera and I use a cellphone camera. There is even an appendix dedicated to them in this book. So why do we need the control a dedicated camera can give?

|

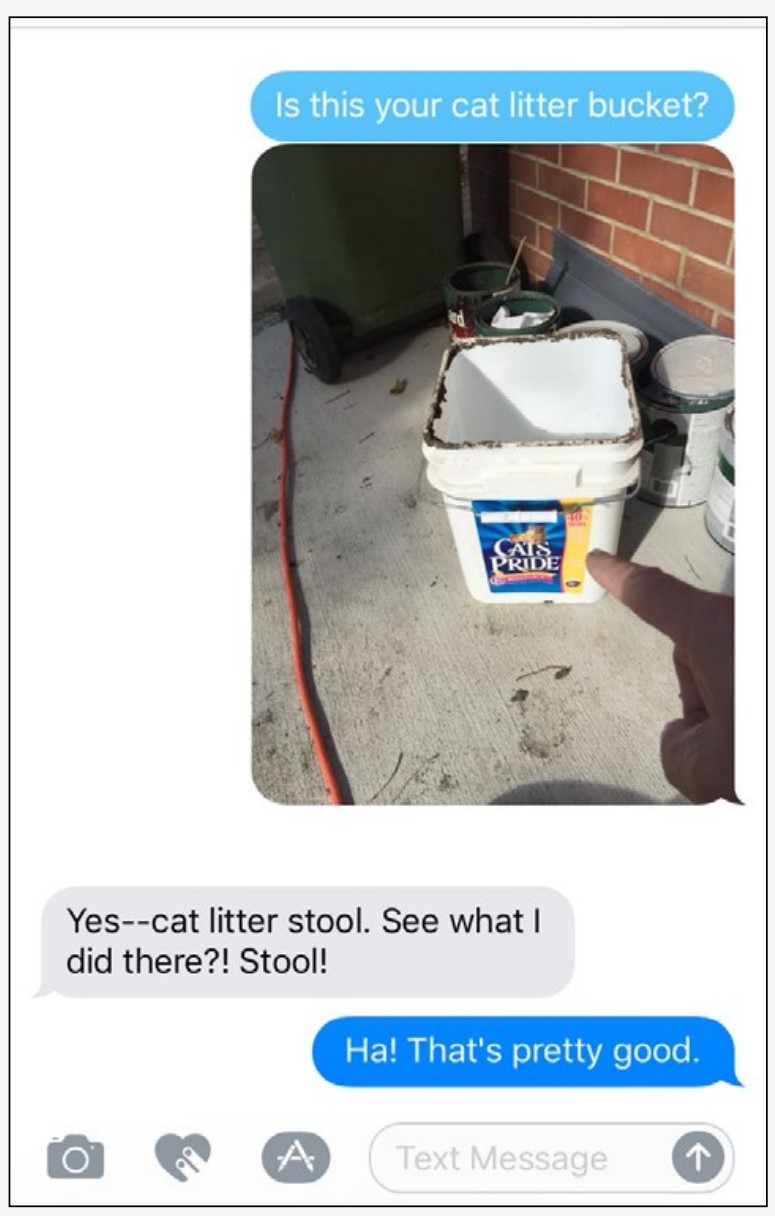

Cellphone camera image. For this one-liner an older cellphone did the job of getting the point across.

|

Analogy: Drawing

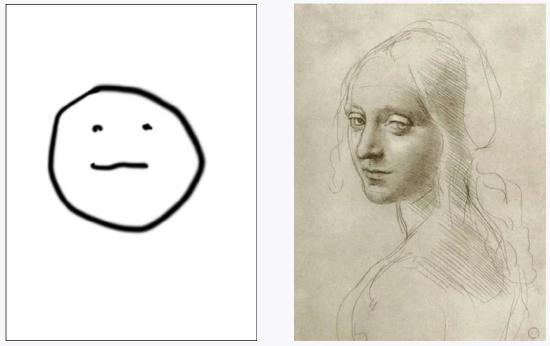

I am assuming you know how to draw a face. A somewhat round shape containing two marks for eyes and a curve for the mouth. There is nothing wrong with drawing a face like this. As a matter of fact, it is amazing how fully packed with information it can be. You can probably think of at least a dozen ways of controlling the face’s qualities, even just by changing the mouth line to show emotions.

Now watch someone who has learned how to control the process of drawing. A line here, a line there, and before you know it a wonderfully nuanced life-like face appears like magic. It is a different level of control.

That is what this book is after. Not how to draw faces (of course), but to control the photographic process in much the same way. Although there is some control you can have with a cellphone camera (and hopefully your cellphone photographs will be better after this book), a dedicated camera allows you much more control. Like drawing, photography is communication. Communicate beautifully.

Analogy: Writing

Here are two ways of saying the same thing:

“I was the shadow of the waxwing slain by the false azure of the window pane”

“I was a bird that flew into a window”

|

Face drawings by the author (left) and Leonardo (right). Both show many aspects to a face and both are useful for some things.

|

...both communicate the same thing, but Vladimir Nabokov says it differently in the first quote—in a way that burned into my brain cells for years to come. He can really control his words.

You have your own quotes that burn themselves into your brain cells. Perhaps a verse in a song that is just soooo good, so precise, so right. My sincere hope is that his book will help you make photographs like that.

Control of words is a reason people take writing classes. You have known how to write from an early age—you don’t need a writing class for that. But like the drawing analogy: if you want to write well, you need to learn how to control your words.

Think of it this way: If you can write a text message to someone, why might you need to take a writing class? Hopefully the answer is obvious to you.

This is not to say that the language used for text messages is somehow bad—but it is a language that has developed for a very narrow use. Just like the language of cellphone photographs where you just point and shoot.

The End of Photographers

After Macintosh computers were introduced, it was widely predicted that the job of graphic design would cease to exist. Everyone could have designers’ tools—layout applications professional enough to do any job and hundreds of fonts

|

This text message is not one for the ages, but it functioned just fine to let me know whose seat this was.

|

But these predictions were wrong. The job of design is even more important now than it was back then. Effective design needs both the controls and the talent to use the controls.

A few years ago, when the image quality of cellphone camera images started to resemble those from bigger cameras, it was predicted that the job of photography would cease to exist. With the image quality of cellphone cameras, who would need a photographer any more? Some news outlets even experimented with having reporters submit their cellphone photographs for publication.

As it turns out, photographers are still needed, and those experiments doing away with them didn’t work out so well. Look at media outlets, and identify the number of images you find that have been taken by non-photographers (you can tell). Unless it was one taken by a Kardashian, you won’t find any at all, even with the most local newspaper.

The reason photographers are still needed is that they have the talent to make engaging images—and the controls necessary to utilize that talent. In most situations those controls rely on dedicated cameras.

As a writing class won’t turn you into a writer, this book won’t turn you into a photographer. But it will give you insight into how photography and photographers work. And give you more control over the process.

|

Watchman Island off the coast of Labrador. The cellphone camera did a fine job of taking this photograph through the airliner window and the image holds up well at this size on the screen. In other words, I didn’t need the control and quality of a DSLR for this particular image.

|

How long do you look?

I haven’t timed myself looking at photographs, but by looking at other people scooting a thumb up and down on their phones, I can guess that most photographs get less than a half-second of our attention.

The aim in this book is to make this attention last longer by learning how to control the camera and therefore the resulting photographs. To get that thumb to waver over the screen then slowly swivel off to the side. Perhaps even to elicit an emotion. A phone turn. Maybe a pass to someone else.

There are two ways to get this to happen. Either take a picture of something incredible or take an incredible picture. Or both.

Incredible can mean many things in this context. For the subject to be incredible it could be anything from a very cute kitten to something blowing up real good.

For the picture to be incredible it could be anything from enveloping light bathing a scene to a heartfelt rendering of an fleeting emotion. Or much more. I have been looking at photographs for a long time, but I never cease to be amazed at the amazing new images I see. Every term that I teach an introductory photography class I see students coming up with incredible things that I could never do. Sometimes it is brash and loud. Other times it sneaks up on you. Sometimes it is funny, and sometimes full of pathos.

The Act of Pointing

Photography is communication. It is communication firmly tied to the visual world in which we live. In its most basic form, it is the act of pointing. Hey, look—this is what I like, this is what I feel, this is what I find interesting.

I tie my photographic anchor to writing. Many people tie photographs to music, and there are certainly many parallels (think tones). You could just as easily tie photography to any other creative endeavor—dance, theater, humor, sculpting. People use all of these media for really one thing, which is communicating to fellow people.

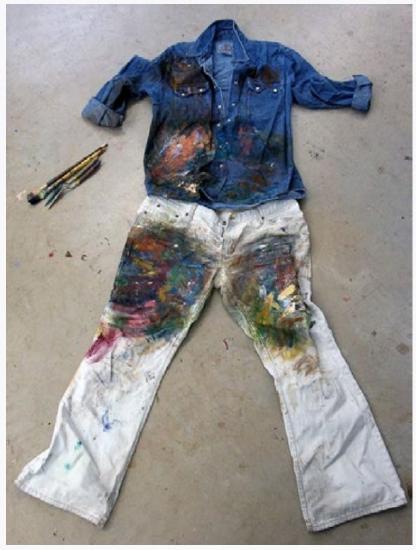

Photography is a cool medium. I envy painters, who touch and smell when they work, who can get into their creation and even get it all over them. Photography is not like that. The camera is a separator, the visual world is a limited pallet.

But like a haiku or a limerick, those limitations can make things more interesting. When photography is done well, it can be as incredible as any other medium.

Technique

This book is mostly technical. You have to learn scales before you can compose a meaningful song. You have to learn timing before you can be a good actor. This book covers the tools used to make incredible photographs.

|

Literally pointing (I didn’t have a telephoto lens with me for this grizzly bear in Waterton Park)

|

|

Lauren Kahler, painting clothes

|

Hopefully you will be making prints from some of your photographs as you work through the book. There are several reasons for this. In a purely practical sense, prints show defects in an image much more readily than the screen does. For example, if your image is too dark on the screen, the brightness range of the screen will mask that defect. The limited brightness range on a print will not.

Despite what you might think you know, printed material demands more attention than the rather ethereal material on a computer screen. I often see this demonstrated with students (oh, I didn’t notice that on the screen). Studies done bare this out. People pay more attention when things exists in the physical world. They are perceived as more permanent and less fleeting. Because they are.

Some things are better in a fleeting medium like the screen. Facebook comes to mind, and do you want Twitter or even the news in a permanent printed form? Even this book?

Every day we are taught by example that screen material is to be consumed quickly and then we should move along. That thumb moving up and down over the phone is learned behavior. Do not engage (I really didn’t want to know what they had for dinner), just move on. Thumb up. Thumb up.

How meaningful is it when someone sends you a birthday greeting or love letter as an email or a text? Wouldn’t you rather have it as physical object? Something another human actually touched? Photographic prints can be like that actual card.

The final reason you should print is that photography is a social medium (like any other). An important way to learn the aesthetics of photography is by communicating with others. What do you like? What works? What doesn’t? How could the image been done differently? These conversations work much better with prints than with screen images.

Printing a selection of your photographs has other advantages in learning how to choose and edit photographs. It will make you a better photographer, even if you never print a photograph after you get through with this book.

|

One of the photographs above was taken in the middle of the night. The other was taken in the middle of the day. Can you tell which is which? |