5.3: Identity and the body

- Page ID

- 107385

Identity and the body

Contemporary artists use the body as both medium and subject.

1980 - now

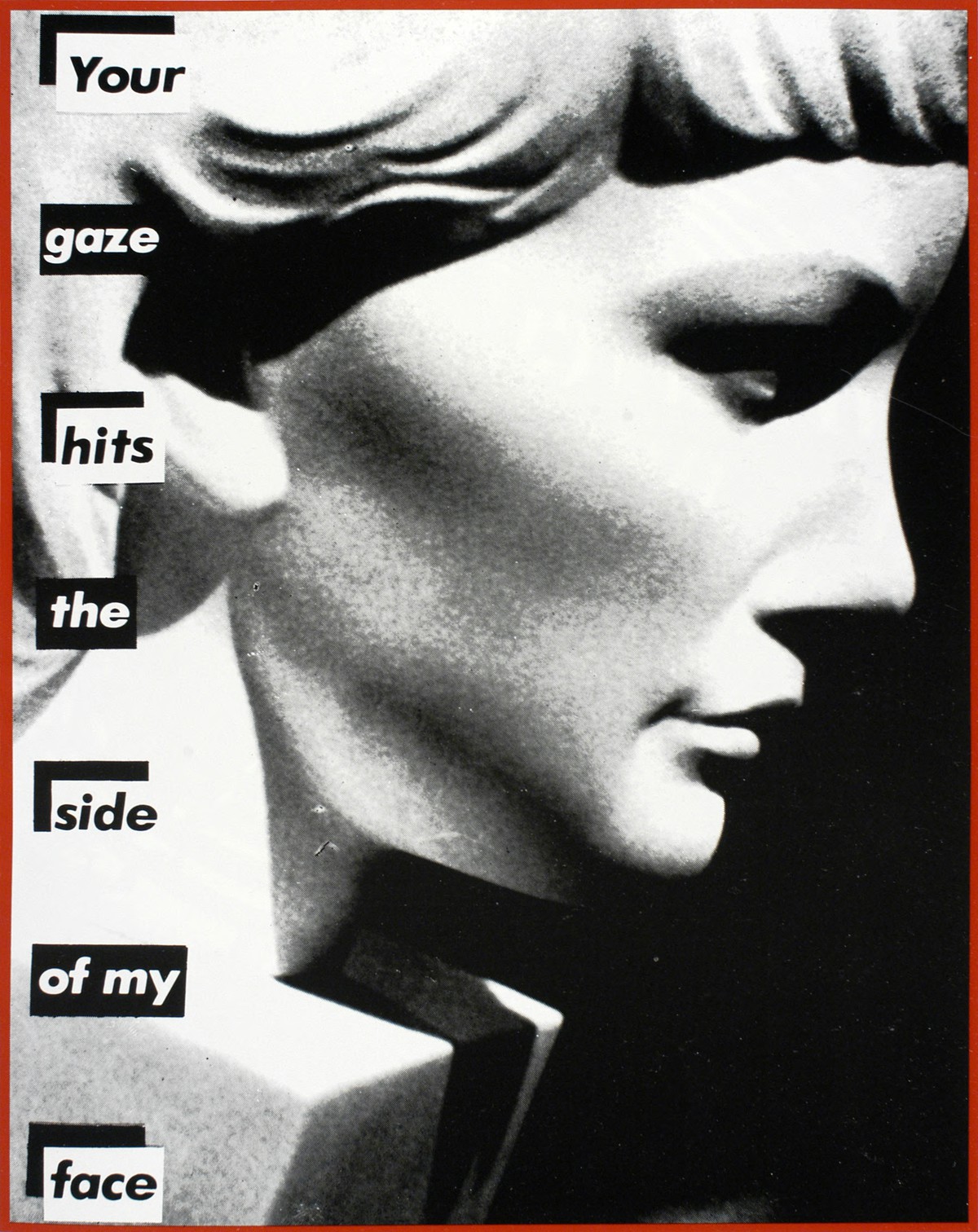

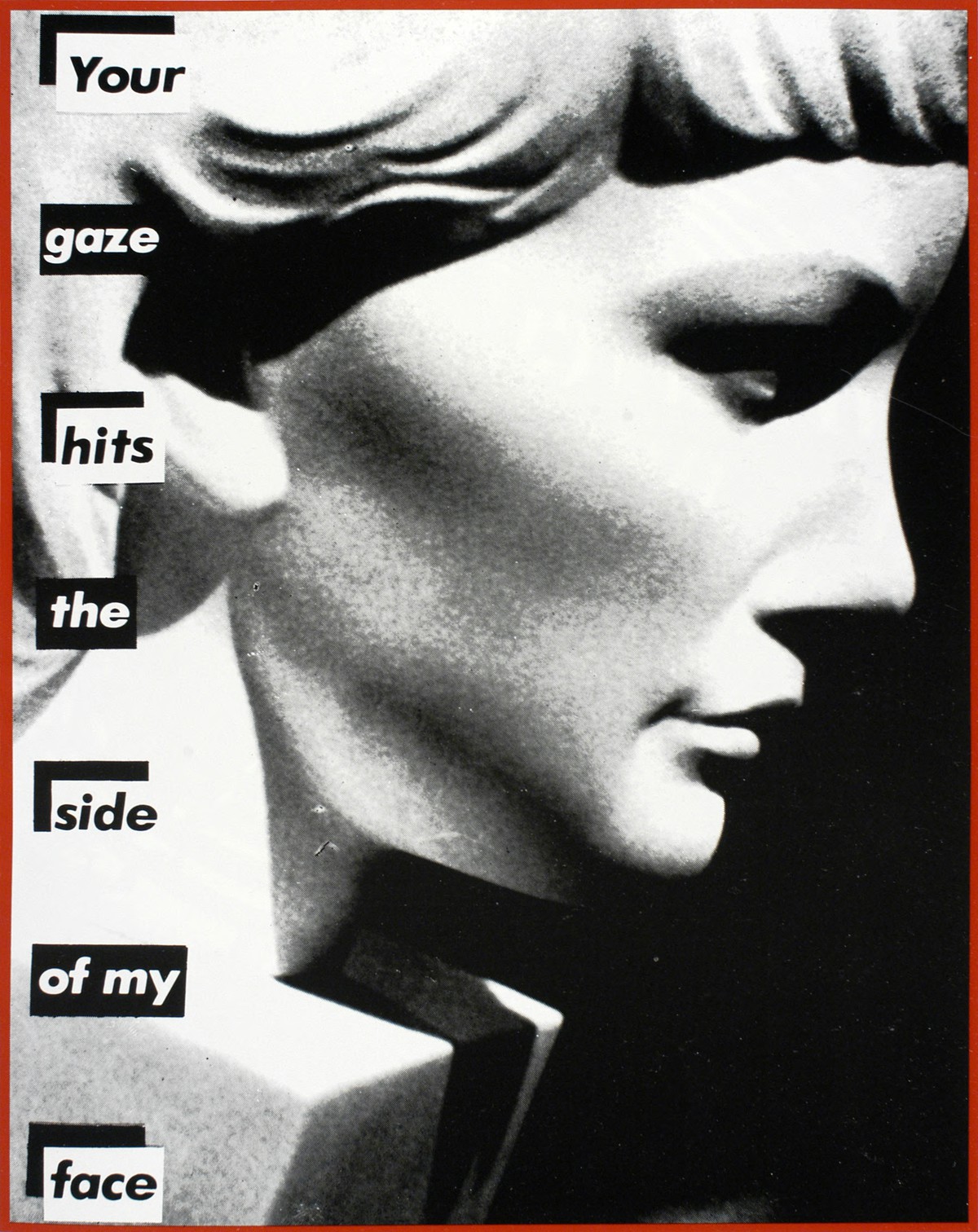

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your gaze hits the side of my face)

Has an artwork ever been more direct in acknowledging that the simple act of looking is a gendered (and gendering) act? “Your gaze hits the side of my face,” admonishes Barbara Kruger in Untitled (1981). The phrase is made stark and impersonal by arranging the words in a vertical stack, like those of a ransom note, to the left of a photograph of a female portrait bust in profile. Notice how the head is equally depersonalized; a stylized version in the classical tradition whose neck disappears into a block of stone, the suggestion here is that women are rendered inert in the act of being looked at. With an assumed male viewer — the subject of the possessive phrase “your gaze” — the subject of the portrait bust readily conforms to patriarchal fantasies of the passive female object.

In 1981 the concept of the male gaze spelled out a crucial problematic of feminist theory. Could women truly be liberated from the objectification implied in this act of being looked at? John Berger in his 1972 book Ways of Seeing described the history of Western oil painting as a catalogue of submissive nude women arranged for the pleasure of male viewers. Kruger confronts this tradition head on. The phrase “male gaze” referenced in Kruger’s title is taken from Laura Mulvey, who coined the phrase in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” a landmark text of feminist theory.

Kruger’s art is characterized by a visual wit sharpened in the trenches of the advertising world where the savvy combination of graphic imagery and pithy phrasing targeted a growing population of consumers in the post-World War II years. The portrait bust she uses for Untitled (Your gaze hits the side of my face) is a found picture, one of any number the artist would have encountered in her early career in graphic design. This included a stint at Mademoiselle magazine, whose glossy pages were a virtual catalogue of stereotypical images of femininity. In the late 1970s, Kruger began to choose for her photomontages images of women that were often heightened examples of such stereotypes to which her addition of text would, often humorously, expose and thereby deconstruct the supposed realism of such imagery.

A 1982 work, for example, shows a silhouette of a woman’s body partially outlined by dressmaker’s pins and leaning forward in a chair marked with the words “We have received orders not to move.” The text here is laid across the body’s midsection, adding another layer of the idea of being pinned in place. The sense that women were trapped or immobilized in the act of being seen runs throughout her body of work from this period and underlines how common this kind of depiction of women was in advertising, particularly during the mid-twentieth century, the period from which many of Kruger’s images were culled.

Kruger offers some resistance to the objectifying gaze of the titular male viewer. Only hitting the side in Untitled (Your gaze hits the side of my face), one imagines it bouncing off as if merely ricocheting. But it nevertheless makes strategically visible the tacit assumption of Western visual traditions: women are looked at; men do the looking. In feminist terms, this means that women are negatively defined as lacking subjectivity or agency. Kruger staged an intervention, one could say, and it is in this way that her work is considered part of the feminist art canon.

During the second wave of feminism in the 1970s, women artists sought, in different ways, to confront the problem of women’s representation in art. Sylvia Sleigh’s painting The Turkish Bath (1973), for example, renders a group of nude men in a traditional portrait genre usually reserved for women typified by the Neoclassical painter Jean-Dominque Ingres. Other artists, like Eleanor Antin (who also riffs off the classical sculptural tradition in Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, an important antecedent for Kruger) sought to subvert the usual depiction of women through unidealized and un-sexualized representations of the artist’s own body.

A different tactic was to refuse representation of women’s bodies altogether. Mary Kelly’s monumental Post-Partum Document (1975), while an extensive portrayal of female subjectivity in relation to the mother-child relationship in psychoanalytic terms, makes no visual reference to herself or her body. Yet another approach was to develop a separate aesthetic predicated entirely upon women’s experiences: Womanhouse was created by Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago in the early 1970s as a space to showcase feminist performances about rape or installations about menstruation. Finally, there is the use of craft traditions typically associated with the domestic labor of women. Elevating “craft” to a fine art became a symbol of the elevation of women themselves as they strove for inclusion and representation. Kruger’s first artworks, in fact, were wall hangings that reframed craft in feminist terms. Despite the variances in approaches, at issue in feminist art practice was the place of imagery of women and artwork by women within patriarchy and in dialogue with political issues around gender and sexuality.

Kruger’s work differs from her predecessors whose work I have just briefly outlined. She came of age as an artist at a time when many were taking existing imagery and then re-staging it in slightly altered form. The term for this was “appropriation,” and it defined the strategy of a new generation of artists who wanted to refute modernism through invalidating ideas of originality, uniqueness, and even authorship. They became known, as did Kruger, as postmodern artists. Interestingly, many of these artists were women. Already critical of modernism because of its male-centered ideology, they filled the ranks of postmodernism to such extent that the critic Craig Owens described this congruence as a “crossing of the feminist critique of patriarchy and the postmodernist critique of representation.” Sherrie Levine re-photographed a suite of images by the photographer Walker Evans in order to void his authorship. Cindy Sherman appropriated the cinematic tropes of Hollywood whose stock and trade was the vulnerable female in trouble and re-staged them using herself as model. While feminist art (and postmodern art) was largely a white movement, later artists such as Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems or Kara Walker would expand upon these earlier artistic strategies to address the intersection of race and gender.

The art of the “Pictures Generation” as these postmodern artists came to be called, was glossier, slicker, and more enamored of media culture than what had come before, to such an extent that the cultural critic Fredric Jameson worried that art and advertising had become one. Of course the aim was to critically analyze such imagery; Kruger redeployed its seductive techniques, usually pressed into the service of enticing consumers (and historically much of it was aimed at women consumers), to expose the subtle and pervasive ways in which stereotypes of gender roles were reinforced through advertising and cinema (later works by Kruger would target consumerism directly).

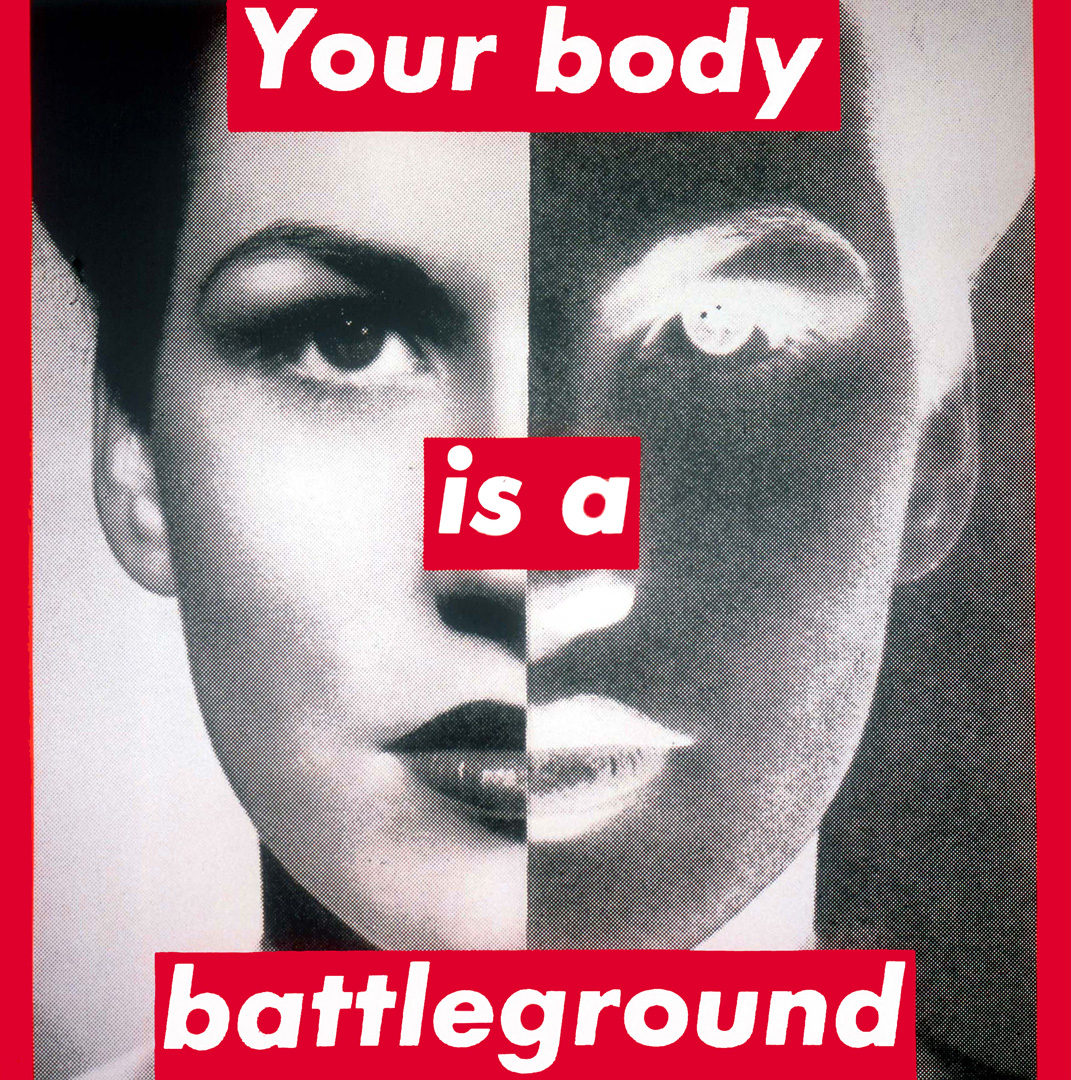

Deconstructing the supposed naturalism or ordinariness of these cultural fictions of femininity took on, within the larger political context of the feminist movement, an often agitprop or activist gloss. “Your body is a battleground” was produced for a 1989 women’s march on Washington. Confining her imagery to black and white with the eventual addition of red was clearly a nod to the photomontages of Russian avant-garde artists in the early twentieth century. In the first years after the Russian Revolution, artists sought to harness the power of technology using photography and film to reach mass audiences and unmask false ideologies.

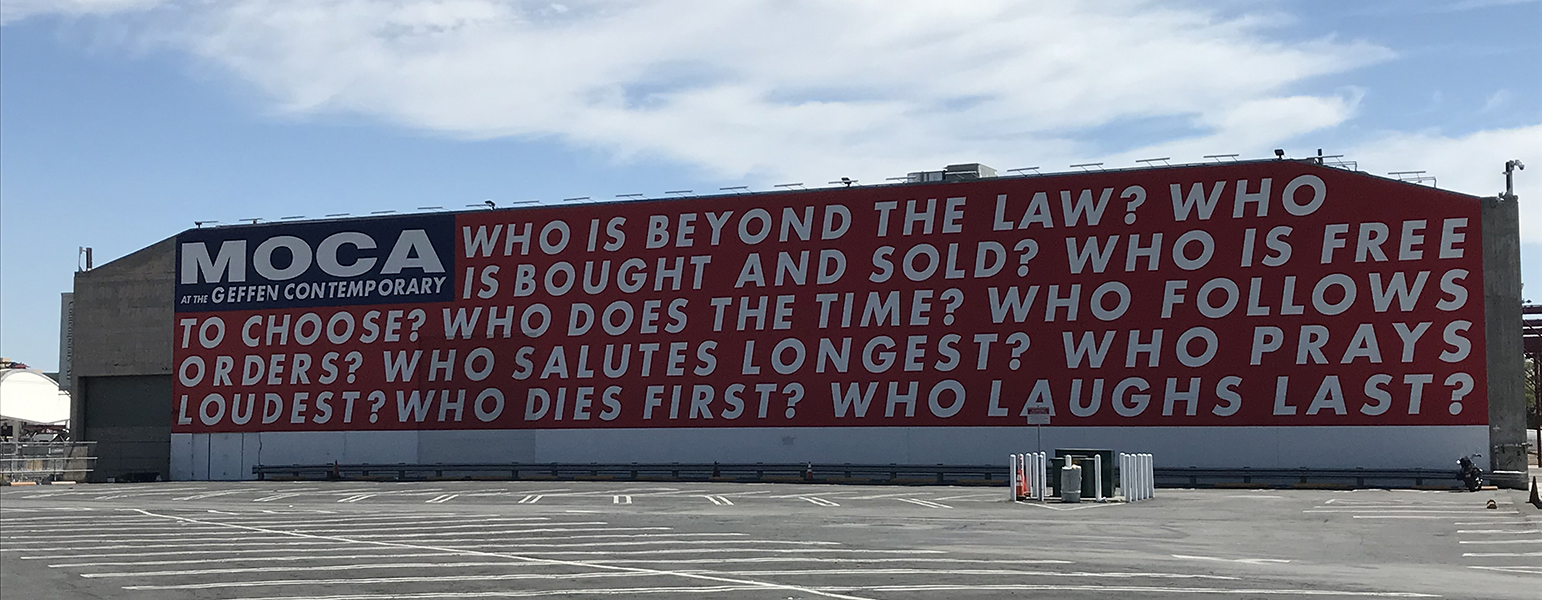

Much like the factory murals and posters of Russian avant-garde art, Kruger sought a broader audience outside the gallery. Her work would appear on billboards, train station platforms, bus stops, public parks, and even matchbook covers. In the early 2000s the street clothing brand Supreme acknowledged that Barbara Kruger was an inspiration for their logo, a white Futura font within a red box. Despite its critical stance toward the advertising industry, Kruger’s unique graphic style couldn’t help but ultimately become influential in packaging and product design. Had Jameson been right about the collapse of art and advertising? Did the promotional and publicity structures of a consumer society eventually absorb postmodernism and thereby render its critique neutral?

Additional resources:

- Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen, Volume 16, Issue 3, (Autumn 1975): 6–18.

- Craig Owens, “The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism,” in Hal Foster, ed., The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture (Seattle: Bay Press 1983): 78.

Jane Alexander, Butcher Boys

Men or beasts?

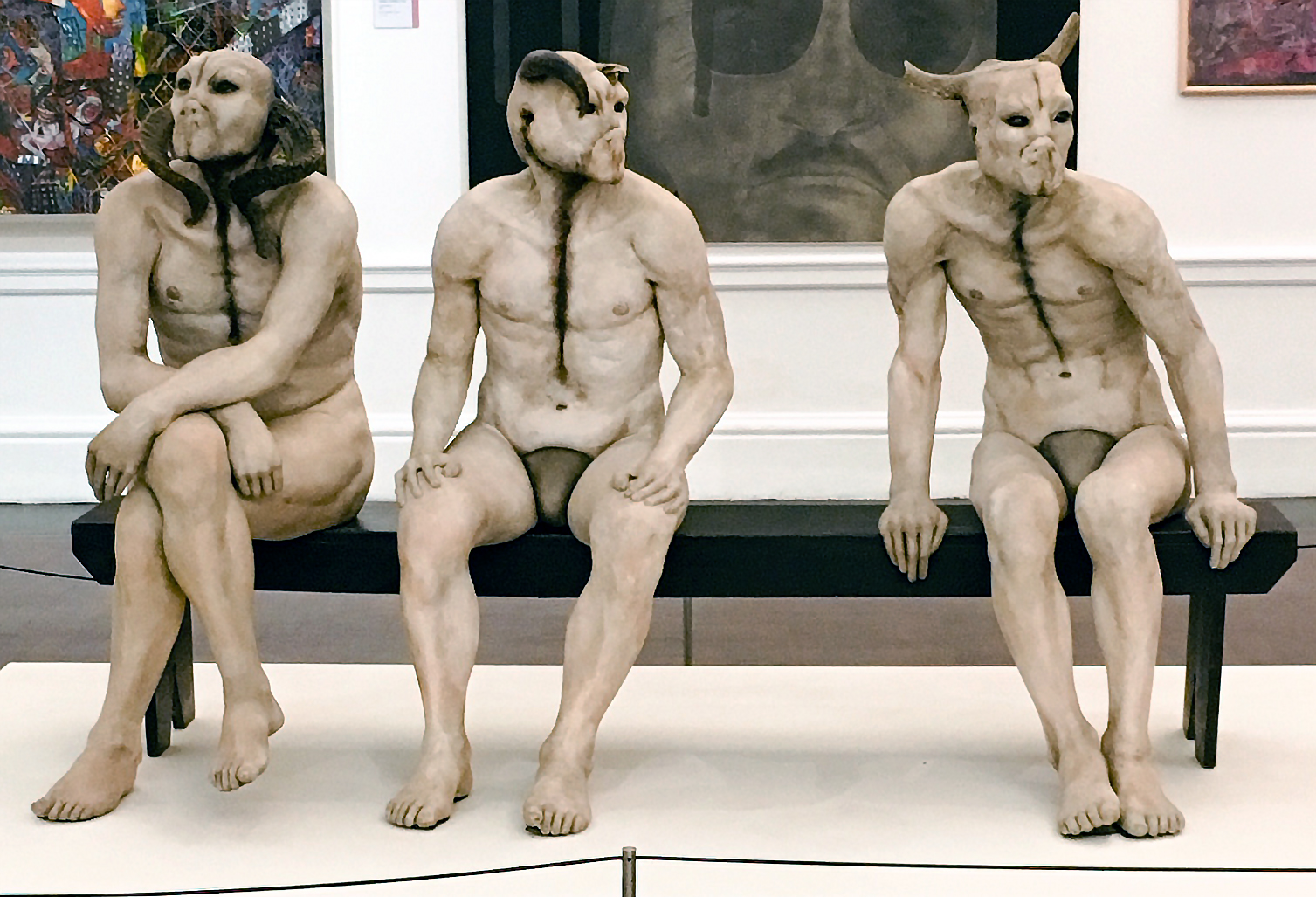

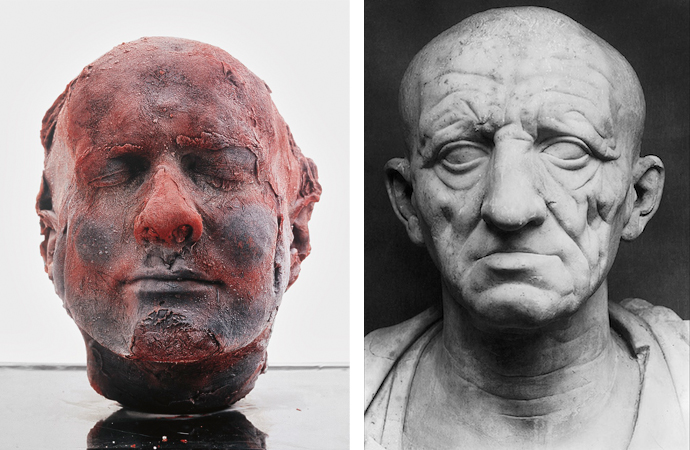

Inside the Iziko South African National Gallery there are three monstrous figures that sit casually on a wooden bench thoroughly indifferent to their environment. Their indifference confounds gallery-goers who struggle to answer questions such as: Are these figures men or beasts? What do these figures represent? South African artist Jane Alexander created the life-sized sculpture, titled Butcher Boys, in 1985/86 while a graduate student at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. The figures are composed of reinforced plaster, animal bones, horns, oil paint, and the wooden bench on which they sit.

Uncanny resemblance

The forceful impact of the Butcher Boys resides in the figures’ uncanny resemblance to us. Their figures are not all together unfamiliar within the history of art. There are flashes of resemblances to the familiar and celebrated figurative sculptures of the Greco-Roman tradition. The scale, definition in form, and physical proportions seen in Alexander’s Butcher Boys echo those of the Hellenistic Boxer at Rest by Apollonius. Other stylistic associations to seated and contemplative figures, such as the now notorious monument to Cecil John Rhodes, can also be made.

However, Alexander’s figures are not, of course, continuations of these figurative traditions. Rather, hers are a critique in which she transforms the symbolic body of heroic/stately strength into a grotesque mockery of classicism. Their scarred flesh, exposed spinal bones, horned crania, and vacant black eyes undermine any sense of beauty to be found in their carefully modeled bodies. The Butcher Boys discomforts us because their form comes too close to that of humans, yet their anatomy is riddled with nonhuman elements and mutations. Alexander has eliminated, or grossly mutated, each figure’s sense of sound, sight, smell, and taste. Each figure has irregular concavities where, perhaps, ears once protruded, but have otherwise been removed. They have the slightest suggestion of nasal cavities, which makes their lack of any oral cavity all the more prominent and perplexing. Additionally, deep scars traverse the larynx, past the heart and end just above the navel. Their limbs and torsos are decidedly human. Their arms and legs are without mutation, however, deep wounds down their spinal columns expose fragments of bones.

Viewers of the Butcher Boys confront an uncanny image of brutalization. The figures are not sympathetic victims or overtly threatening monsters. They are intimidating; yet, the violence against their bodies elicits a certain amount of empathy. They are unnamable beings without classification. They are neither man nor beast but rather both.

Crime against humanity

The National Party in South Africa came to power in 1948 and was founded on white-supremacy and driven by an ideological platform of extreme segregation known as apartheid, or in Afrikaans, “apartness” or “apart-hood.” In 1985, the same year Alexander created Butcher Boys, South Africa was consumed by violent and non-violent resistance to apartheid. This was followed by a state of emergency (the second) issued by the National Party and state-sanctioned violence.

The earliest apartheid laws were distinctly concerned with the control and management of South Africans to assert and maintain white supremacy. The first two laws passed by the apartheid government were anti-miscegenation laws that criminalized marriage and sexual relations between “a European and a non-European.” The third, the “Population Registration Act” of 1950, forced citizens to register with the government according to its racial caste system. By 1973 the General Assembly of the United Nations recognized South African apartheid as a “crime against humanity.” This reality, of course, had long been recognized by those who fought against the regime. Despite growing international condemnation and internal resistance, the National Party continued to violently oppress any challenge to their power throughout the later decades of the 20th century. Given this context of brutality, Alexander’s Butcher Boys are commonly linked to the violence of apartheid and particularly the second state emergency. Art critic Ivor Powell wrote that “the Butcher Boys . . . [is] probably the most enduringly iconic image of the sinister and apocalyptic brutalisations of apartheid.”[1]

Art, trauma, and political violence

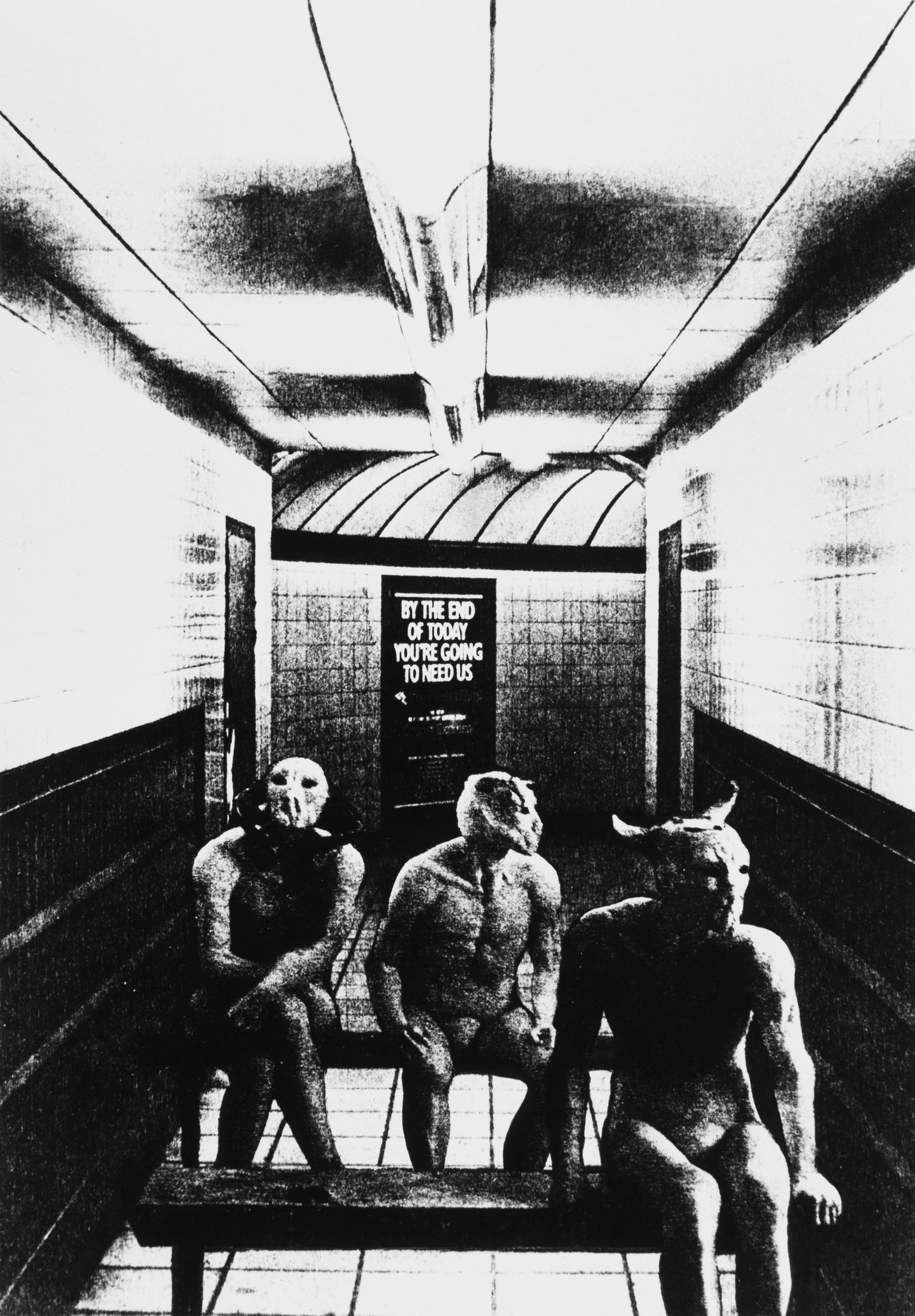

Alexander, featured the Butcher Boys in photomontages, such as BY THE END OF TODAY YOU’RE GOING TO NEED US (1986), Ford (1986), and Transmitter (2007) among others. Since they are so commonly associated with apartheid violence and trauma, their presence becomes a potent symbol of that violence and trauma. Through the repetition of their image in photomontages, outside of the white-walled gallery space, Alexander appears to provide evidence of the Butcher Boys’ existence within our world. In these photomontages, Alexander blurs and obscures the visual field just enough to give a candid or accidental aura to each image. It’s as if the Butcher Boys are unwitting subjects within the series of photographs taken from everyday life.

By placing the Butcher Boys in a variety of scenes—on the outskirts of Cape Town, within a salvage yard, and waiting for a subway train—Alexander moves the audience beyond the physical components of the Butcher Boys and into a deeper consideration of their existence. This is the key to the work’s iconic status. It is not just the shock of the physical, but even more so, the chilling recognition of the environment as the source of their trauma.

What Alexander achieved with Butcher Boys can be likened to Picasso’s Guernica. Both were created in the context of atrocities, which the governments (Franco’s Spain and the National Party’s South Africa respectively), inflicted on their own people. Guernica is so named because it depicts the bombing of a civilian target, the Basque city of Guernica in Spain. Its subject is local and specific; however, its reception propelled it into a totalizing indictment of fascism, much in the same way that Goya’s Third of May, 1808 depicts the events of a singular day of Napoleonic violence in Spain, but has come to represent the horrors of war more generally.

Both Picasso’s and Goya’s paintings highlight an unsettling normalization of political violence. They give their viewers a chilling assessment of the unaffected banality of the environments from which these atrocities sprang. In so doing, these paintings resonate beyond their record of time and artistic movements as they reflect our seemingly endless slippage into enacting and accepting brutal violence. What sets Alexander’s Butcher Boys apart from Picasso’s and Goya’s iconic paintings is that her work does not point to a singular event. Rather it is the totality of the apartheid’s regime of violence that is called into question.

The Butcher Boys may be part man and part beast. Their identity as such, however, is less important than what they represent—violence and trauma. The Butcher Boys can be seen as a response to the public’s willingness to depersonalize violence by ascribing such behavior to the monstrous. To acknowledge the truly violent nature of humankind is to implicate one’s self in a relationship to such atrocities. These bodies visualize violence in a way that emphasizes how we dehumanize each other. It is easier to dehumanize violence than it is to see humanity in violence, and this transitional state of being between man and monster is where the Butcher Boys reside.

Notes:

- Ivor Powell, “Inside and Outside of History,” Art South Africa vol. 5, no. 4 (Winter 2007), pp. 32-38.

Additional resources:

Iziko South African National Gallery

Tate Modern, “Who is Jane Alexander?”

South African History Online, “Jane Alexander”

Pep Subirós, ed., Jane Alexander: Surveys from the Cape of Good Hope (New York: Museum of African Art, 2011).

Sophie Perryer, ed., Personal Affects: Power and Poetics in Contemporary South African Art (New York: Museum of African Art, 2004).

Sue Williamson, Resistance Art in South Africa (Southern Africa: David Philip, Publisher, 1989).

Jamie Wyeth, Kalounna in Frogtown

by TAYLOR L. POULIN and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Jamie Wyeth, Kalounna in Frogtown, 1986, oil on masonite, 91.4 x 127.3 cm (Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1992.163) ©Jamie Wyeth, a Seeing America video speakers: Taylor L. Poulin, Assistant Curator, Terra Foundation for American Art and Beth Harris

Additional resources

Marc Quinn, Self

The shock of the new

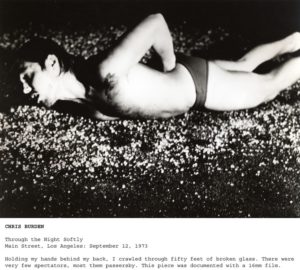

Shock value has been an important aspect of art since the nineteenth century. But is provocation always merely a case of superficial attention-grabbing, or can it ever have depth? Marc Quinn’s Self, a sculpture depicting the artist’s head made from his own frozen blood, is a perfect artwork for mulling over such questions. Shock is the probably the foremost element in its success and lasting impact on viewers: once seen, Self is not easily forgotten. The sight of blood often has this effect. For some it is an extremely distressing spectacle in its own right, and even for those of us used to transgressive artistic acts, the public display of real bodily fluids still retains its sense of taboo. But once the shock wears off, what are we left with? Does its meaningfulness erode over time, like a joke whose amusement diminishes on each rehearing?

Process and meaning

It is probably wise to first acknowledge the extraordinary amount of preparation and the lengthy ordeal Quinn put himself through to create Self. First, he took blood from his body – as you would do during a blood donation – over five separate sessions to stockpile a total of ten pints (5.7 liters). He then made a cast of his head by covering it with an all-over mask of plaster of Paris (leaving breathing holes for his nose). This perfect impression of the artist’s facial features was then removed, filled with the blood and frozen. When it was solid, the blood head was mounted within a Perspex box filled with silicone oil at a subzero temperature.

This careful, quasi-medical process indicates the seriousness and meticulous planning that lie behind Quinn’s shock tactics. Ten pints is the average amount of blood in a human body, so among the other effects of Self is to make the spectator aware of the modest volume of this vital substance required to sustain a life. The freezing process is also one that might trigger thoughts of other modern medical practises such as cryopreservation (the technique of storing biological samples — and sometimes whole bodies — by keeping them at low temperatures for future regeneration). Quinn’s sculpture is, among other things, a life support system. It therefore suggests wider issues of life and healthcare in the modern world: Self is as dependent on science as our own lives are, and it leaves us space to contemplate the magical promises of medical technology, as well as its limits.

Quinn’s education as a student of History and History of Art at the University of Cambridge can be seen as a vital component of his work as a whole, and here his engagement appears to be with ancient tomb sculptures. Much of what we study as art from early civilizations (such as from Egypt and China) is from burial chambers, where the intention was to preserve bodies and spiritually conquer death. Also, one of the chief purposes of all portraits has been to conserve an individual’s legacy. Quinn’s engagement with cryopreservation in a gallery setting reminds us of art’s ancient role in ensuring posterity.

Blood simple

Disregarding the startling choice of sculptural material, there is little in the appearance of Self to cause alarm. In some respects, its presentation is rather archaic. It is a portrait bust, a format which originates in Europe with the Romans, and it sits on a plinth behind a glass case, much like an exhibit in a museum of antiquities. The head is subtly upturned with its lips pursed and eyes closed, giving it a sense of peacefulness and serenity — as if asleep or gracefully deceased. The casting process that Quinn used has picked up many tender textures from the surface of Quinn’s face such as the eye lashes, creases on lips and the folds of flesh on the ears. A sense of the macabre is thus conveyed only through its bruised, red and blue coloration, and arguably also the surface texture which bears marks left behind from the mold used in the process of casting and makes the head look scarred or decayed. Casting is a very old sculpting technique, but it looks as though Quinn is making reference specifically to the tradition of death masks, which were used by the Romans to record the physiognomy of deceased family members.

A literal portrait

Unlike more traditional materials of western sculpture such as marble, blood is not durable and will decay if not frozen. Similarly, the process of casting is traditional, but usually it is done with bronze or other precious metals, and not a bodily fluid. Value therefore becomes a significant theme, as blood — unlike marble and bronze — lacks monetary worth and yet is essential to life. The use of bodily fluids increases the sculpture’s status as a ‘true’ self-portrait in which the artwork serves not only to depict the artist but is also composed of a part of the artist’s own body, his DNA. As mentioned before, the presence of a refrigeration unit underscores the sculpture’s dependence on a source of power, arguably increasing its sense of vulnerability. Quinn has commented on the autobiographical dimension of Self saying that it reflects his alcoholism, as it is entirely dependent on electricity, just as he was reliant on alcohol. This self-expressive aim is also attested by Quinn’s aim to pay homage to Rembrandt, who repeatedly created self-portraits in the latter stages of his career, by making a new 10-pint blood Self every 5 years.

Sacrifice

Historically, blood is associated with sacrifice and ritual, such as in the Aztec Empire and Mithraism (an ancient Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras), and in some religions had been applied to sculptures in order to “animate” them. In Christianity the blood of Christ is also sacred and celebrated at the Eucharist. In other contexts, blood is symbolic of truth and family lineage — one speaks of a “bloodline” and agreements have sometimes been sealed by mingling blood. Quinn’s self-portrait can be identified in the crossroads of these various associations, indicating the potent, generative powers of blood, the veracity and individuality of the artist’s personal identity, as well as his self-sacrifice in the name of art.

The trope of the artist as a suffering, outcast martyr has been with us since at least the Romantic period. And it is not unrelated to the trope that this essay began with: that of the artist as provocateur, intent on shock tactics to turn heads. According to this stereotype, artists should behave like outsiders who position themselves beyond society, only in order to castigate and shock it with their piercing commentary. This tradition was given its most forceful early voice with Manet and his provocative works of the 1860s with such works as Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. In the fierce competition of the art world every young artist needs to court notoriety if they want to be noticed — quiet conservatism seldom makes for front-page news. Causing shock is relatively easy, but the outrage quick wears off if the work lacks dimension, and there will be many forgotten names in the history of twentieth-century art, music and cinema who resorted to the kind of superficial shock whose impact petered out all too quickly.

Does Self fall into this category? A defense of its merits would point to the breadth of themes addressed in this essay: its painstaking process, its appropriation of medical technology, its art-historical reference points and its aim to act as a vehicle of the artist’s self-expression. Self, such an argument would run, serves as an example of provocation with a purpose, where medium, technique and message coalesce, and the art achieves both a memorable aesthetic and a satisfying quantity of conceptual ballast.

Additional resources:

Lucian Freud, Standing by the Rags

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Lucian Freud, Standing by the Rags, 1988-89, oil on canvas, 66.5 x 54.5″ / 168.9 x 138.4 cm (Tate Britain, London)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman Feeding Bird), from The Kitchen Table Series

by LAUREN HAYNES, CRYSTAL BRIDGES MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART) and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman Feeding Bird), The Kitchen Table Series, 1990, gelatin silver print (printed 2015), 27.94 x 27.94 cm @ Carrie Mae Weems (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (billboard of an empty bed)

Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) is a stark, black-and-white image of the rumpled sheets and pillows of an unmade bed. The depression in the center of each pillow, suggesting a recent presence, conveys a profound sense of intimacy. But this scenario is in jarring contrast to its public location—on a billboard. First exhibited on the streets of Manhattan, this evocation of absent bodies soon came to define all of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work up until his death in 1996 from AIDS-related causes. The artist is most known for ephemeral installations: a pile of candy in a corner (below), a stack of posters on the floor, or strings of lights dangling from a ceiling—all of which recall the reduced visual and formal language of Conceptual and Minimalist art from the 1960s and 1970s.

Yet Gonzalez-Torres didn’t merely reference the work of earlier Minimalist artists like Donald Judd and Dan Flavin—he introduced a specifically contemporary note into his work. In the late 1980s and early 1990s artists were asking new questions around the construction of identity—including gay identity. For instance, the lights in his work were redolent of the environment of a dance club (left), and the candy on the floor was a perverse reference to the drug AZT used to combat HIV. And the bed? Much like the paired wall clocks he created the same year entitled Perfect Lovers that marched slightly out of step with one another (one is a few seconds off), the censored image of same-sex love slowly makes its imprint.

Bed’s sexual politics

By 1987, a new era of gay activism had begun. The Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (ACTUP) formed and suddenly old questions around the relationship between art and politics took on new significance for gay artists. Artist-collectives like Gran Fury used appropriated image and text to convey overt political messages around the politics of AIDS. But Gonzalez-Torres did not follow this route. His disappearing but perpetually replenished works (viewers were allowed to remove a poster or take a piece of candy) took a more elegiac path: it was one in which any direct representation of homosexuality was seldom apparent. Thus his art became an abstract memorialization of loss. Gonzalez-Torres’ memorialization resonated especially during a time when Ronald Reagan (U.S. President from 1981 until 1989) notoriously never uttered the word “AIDS” because of its predominant association with homosexuality. Heads pressed onto pillows in the Untitled billboard thus becomes a simultaneous declaration and disavowal of same-sex love—writ large within an urban landscape.

As an artist, Gonzalez-Torres came of age during the 1980s (he was born in 1957 in Cuba). At that time, Postmodern artists often worked with existing imagery and text, appropriating and examining an increasingly media-saturated world. His earliest work was in that vein. In the manner of Jenny Holzer, who reproduced found slogans or random sentiments on wheat-pasted posters throughout the streets of lower Manhattan in the late 1970s, one of Gonzalez-Torres’ earliest works is a framed photostat (an early version of a photocopy) from 1988 of a sentence. It’s really a jumble of words—white letters on a black background that read “supreme 1986 court crash stock market crash 1929 sodomy stock market crash supreme 1987.” In this way, he offered a poetic commentary on the erasure of gay history by sandwiching a reference to the 1986 Supreme Court ruling that upheld the state of Georgia’s sodomy laws (which effectively criminalized homosexuality) between significant dates in economic history.1

Back to the future

Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) marked an important threshold in contemporary art history. In the late 1980s the art world underwent significant changes. It seemed to many critics at the time that postmodern art existed only to illustrate complex philosophical concepts, while the felt aspects of experience, important for the renewed surge of identity politics (political alliances based on identity, like the women’s movement), were ignored. Foregrounding the bodily dimension of experience, artists like Robert Gober, Kiki Smith and Jane Alexander created sculptural works with visceral impact. Artists began to return to discarded artistic strategies like narrative, constructed (rather than appropriated) forms—anything that would invoke a sense of the contemporary, lived aspect of everyday experience without mediation. Bodies were often splayed upon the gallery floor or its parts protruded from a wall.

Gonzalez-Torres’ art had, in a sense, a foot in both camps: Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) bore resemblance to the billboards Barbara Kruger had done as early as 1985. Her Surveillance is Your Busy Work is one that was unveiled in Minneapolis that year and featured her trademark use of advertising imagery reconfigured with text to correspond to discussions around public space, gender and corporate culture. But Gonzalez-Torres’s image of a disheveled bed was shorn of any textual or even didactic directive. Significantly, the image is of his own bed. Untitled (billboard of an empty bed) suggested—even if it did not portray—a tangible if disappearing presence.

1. This ruling was eventually overturned.

Additional resources:

Print/Out: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, on Inside/Out, MoMA’s blog (April 4, 2012)

Biography of the artist from Oxford University Press on MoMA.org

The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

Art and Photography: the 1980s on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Yinka Shonibare, The Swing (After Fragonard)

With her fingers delicately grasping the thickly coiled rope of a swing suspended mid-flight, a life-sized female mannequin flirtatiously kicks up her left foot, projecting her slipper into the air where it hovers above a tangle of branches. Our gaze is directed from the arch of her foot towards the vibrant trim of her petticoat, gown and coat.

A recreation of a Rococo painting

The Swing (After Fragonard) is a three-dimensional recreation of the Rococo painting after which it was titled, which itself offers testimony to the opulence and frivolity of pre-Revolutionary France. Painted in 1767, Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing depicts a coquettish young girl swinging in a lush and fertile forest and, of course, playfully kicking up her shoe. A sculpture of a bashful cherub looks on, but he is not alone; the female figure is flanked by two male figures lurking in the shadows, one seems to push her swing from behind, as the other mischievously glances up the layers of her dress to catch a glimpse of what is beneath.

Living with History

Living in England, with my colonial relationship to this country, one cannot escape all these Victorian things, because they are everywhere: in architecture, culture, attitude…

Shonibare’s quotations of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century style and sensibility are visually captivating; at the same time, tableaux such as The Swing contain some dark undertones. To begin with, the beautiful young protagonist of Fragonard’s painting has somehow become headless. This is likely a reference to the use of the guillotine during the Reign of Terror in the 1790s, when members of the French aristocracy were publicly beheaded. Drawing our attention to questions of excess, class and morality that were raised by revolutionaries two centuries ago, Shonibare invites us to also consider the increasing disparity between economic classes today, especially alongside the growing culture of paranoia, terror and xenophobia in global politics since 9/11.

As a British-born Nigerian, raised between Lagos and London, Shonibare is especially perceptive to the ways in which issues of access, nationalism and belonging have their roots in modern European history, particularly with regards to the United Kingdom and its relationship to its former colonies. Here is where the specific fabrics that Shonibare utilizes become more relevant, as their symbolism is steeped in histories of cultural appropriation, imperialism and power.

Indonesian motifs, made by Europeans, sold in West Africa

Though tailored in the fashion of eighteenth-century French aristocratic style, the costume that is modeled by Shonibare’s protagonist has been sewn from colorful and abstractly patterned fabrics with quite different origins: the bright golds, reds and blues arranged in geometric motifs across her ruffled skirt are typical of the “African” Dutch wax fabrics that Shonibare has famously used to adorn his figural tableaux throughout his career.

While these fabrics have come to signify African identity today, the patterns on Dutch wax fabrics were originally based on motifs found in Indonesian batiks, and were manufactured in England and Holland in the nineteenth-century. Predictably, the European imitations did not prove lucrative when sold in South Asian markets, so Dutch manufacturers then marketed the textiles to their West African colonies, where they have since been appropriated and integrated into local visual culture.

As such, Dutch wax fabrics as we know them today are the product of the complex economic and cultural entanglements that resulted from European imperialism. As curator Okwui Enwezor has explained, Shonibare uses the fabrics “as a tool to investigate the place of ethnicity and the stereotype in modernist representation. (…) The textile is neither Dutch nor African, therefore, the itinerary of ideas it circulates are never quite stable in their authority or meaning.”

Aesthetics and Authenticity

As fictional as their “African-ness” may appear to be, however, the fabrics have now been completely assimilated in places like Nigeria, where Shonibare grew up. As Enwezor points out, the material is “both fake and authentic, both readymade and original,” not to mention indisputably cosmopolitan.

The question of what is “authentically” African has personal resonance for Shonibare, who, as an art student in London, was shocked when one of his instructors suggested that he make work that expressed his African identity. This conversation prompted him to think about stereotypes and the areas that exist between categories of identity and culture. The artist began using the material in 1992.

In Pursuit of Leisure

What might Shonibare wish to communicate by bringing together these “African” textiles with Fragonard’s Rococo images, or any of the other European masterpieces that the artist has appropriated in his sculptural installations?

In imaging this particular moment in European history, Shonibare wishes to forge connections between imperialism, the aristocracy, and the “colonized wealthy class.” In The Swing (After Fragonard), which is loaded with references to the French Revolution, the Age of Enlightenment and colonial expansion into Africa, Shonibare asks us to consider how a simple act of leisure can be so controversial.

While the leisure pursuit might look frivolous (…) my depiction of it is a way of engaging in that power. It is actually an expression of something much more profoundly serious insofar as the accumulation of wealth and power that is personified in leisure was no doubt a product of exploiting people.

In this and other works, Shonibare chooses stories—including biographies, world events, and works of art—which are already effective allegories concerning race, class, corruption and greed, calling our attention to some of the darker moments in Western history. However, his use of the Dutch Wax fabric, with its spurious origins and its misleading aesthetic identity, serve as a reminder that history and truth are also themselves constructions.

Rineke Dijkstra, Odessa, Ukraine, August 4, 1993

by JOSH R. ROSE

What makes a portrait so compelling? Historically, portraits were reserved for the elite and wealthy, but with the advent of the camera in 1839 portraiture became increasingly democratized and accessible across social classes. Today, we all appear in numerous portraits: family photos, formal school pictures, even the increasingly common “selfie” created for social networks. In an age of ubiquitous portraiture, what makes Dutch artist Rineke Dijkstra’s photograph of a teenage boy standing on a Ukrainian shoreline so evocative?

Working in series

Dijkstra’s photograph Odessa, Ukraine, August 4, 1993 comes from the series Beaches, which was created between 1992 and 1998 across locations as diverse as Poland, Great Britain, South Carolina, Belgium, Coney Island, and the Ukraine. Typically working in series, Dijkstra prefers single subjects documented over time or multiple subjects recorded after moments of intensity, such as new mothers in the days after giving birth or Portuguese bullfighters immediately after a match. Working in series necessitates revealing through comparison.

In Beaches, her earliest series, Dijkstra was interested not just in capturing young men and women on the cusp of adulthood, but the unexpected social and cultural nuances that became apparent by portraying teenagers from different parts of the world:

“I think that in Poland [the subjects’ bathing suits] reminded me of the ‘60s, they have twenty-year old bathing suits and no one cares…They were very easygoing. The Americans had very fancy bathing costumes and the poses were more self-conscious. One girl was really holding her belly in and her mother was behind her yelling ‘You’re too fat.’ She was so unhappy.”[1]

These powerful emotional responses are expressed through intricately captured details across the series Beaches and in each of the individual portraits. Dijkstra draws us in with the details captured using a flash (even in sunlight), from the type of swimming garment (full length swimsuit, speedo, underwear, cut-off jeans) to the expressions on the subjects’ faces (cool, pensive, inquisitive).

Standing on a beach

Dijkstra’s process entailed asking unknown adolescents to pose for her at the shore, and while she set up lighting and prepared her camera on a tripod, her subjects assumed their own stance.[2] As with each photograph in this series, the anonymous boy’s vertical body is set against the rigid horizontals of the shore and horizon. He stands in contrapposto, causing his angular shoulders to protrude up and out, and his gangly frame is sunken in at the torso.

The careful lighting, which one writer has described as “clinical,” starkly contrasts his pale skin against the cool tones of sky, water, and sand. The overwhelming blues and greys are augmented by the boy’s dark red trunks that extend to the sharp bend of his pelvis, appearing unnaturally flattened as if pasted on the image afterward. In contrast to his young body, his mature face stares outward unabashedly, which is daunting when seen in its six foot tall printed form.

Behind his emotionless expression is a self-awareness that appears mature, relaxed, and casual. Dijkstra often strives to capture self-consciousness: “People think that they present themselves one way,” the photographer once stated, “but they cannot help but show something else as well. It’s impossible to have everything under control.”[3] Dijkstra bridges the difficult gulf between self-presentation and photographic representation by allowing the subjects to assume their own pose. Despite choosing nearly identical settings for each photographs in the series, Dijkstra’s portraits transcend simple visual documentation and become revelatory images of the awkwardness and transitory nature of puberty.

Typologies?

Because her title emphasizes location and date but excludes the name, Dijkstra intends for her subject to remain unknown. This insistence on anonymity and working in series is suggestive of a typology, or a system of classification based on type. As Allen Sekula has discussed, photographic typologies became increasingly common at the end of the nineteenth century, linked to the popular pseudo-sciences of physiognomy and phrenology.[4] Another photographer, the German August Sander, is important here. Dijkstra has often stated that Sander was a primary influence on her work and methodology; moreover, he also produced typological photographs.

From 1910 to the early 1950s, Sander encyclopedically documented German people, emphasizing lifestyle and profession as an extensive photographic typology of Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the Twentieth Century). Although his visual approach was modified over time, Sander’s photographs emphasized clothing, tools, ephemera, and setting. In Sander’s 1927 photograph Sisters, the simple folk dresses of the young girls standing on a forest path suggest their lineage with traditional German customs and love of nature (though offset somewhat by their wristwatches!). Sander likely posed and carefully composed his portraits, evident by the visual alignment of the waistline embroidery on the sisters’ dresses.

While the influence of Sander on Dijkstra’s own work is important, there are some key differences, most notably her method of unifying the composition with the shoreline. This, along with allowing her subjects to settle into their own stance, does not classify as much as expose by focusing less on extraneous details and more on the expressions and bodies of her subjects.

Posing as art history

One interesting byproduct of Dijkstra’s method of allowing her portrait subjects to be conscious of the pose they strike is that at times her figures end up in stances that are remarkably similar to famous works of art. In one Beaches photograph from Poland, a young girl unconsciously mirrors a pose similar to that of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. In the Odessa photograph, the young man’s contrapposto and nearly nude figure evokes the idealized youthful males of Early Classical Greek statuary.

These references, which Dijkstra states are unintended by her, are quite evocative, and suggest an ingrained, resonant sense of how late twentieth-century adolescents wish themselves to be portrayed when a Dutch photographer asks them to pose for her while spending their day at the beach.

Special thanks to Sandy Heller, The Heller Group, LLC

[1] As quoted in an interview with Jennifer Morgan, Rineke Dijkstra: Portraits. Hatje Cantz (Institute of Contemporary Art, 2001), p. 80.

[2] Michael Fried, Why Photography Matters As Art As Never Before (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2008), p. 206.

[3] As quoted in Katy Siegel, “Real People,” Rineke Dijkstra: Portraits, Hatje Cantz (Institute of Contemporary Art, 2001) p. 10.

[4] Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (1986), p. 3.

Additional Resources:

Dijkstra’s work at the Saatchi Gallery

Dijkstra in conversation with Abigail Christenson (Tate video)

August Sander on The Museum of Modern Art website

Shirin Neshat, Rebellious Silence, Women of Allah series

In Rebellious Silence, the central figure’s portrait is bisected along a vertical seam created by the long barrel of a rifle. Presumably the rifle is clasped in her hands near her lap, but the image is cropped so that the gun rises perpendicular to the lower edge of the photo and grazes her face at the lips, nose, and forehead. The woman’s eyes stare intensely towards the viewer from both sides of this divide.

Shirin Neshat’s photographic series Women of Allah examines the complexities of women’s identities in the midst of a changing cultural landscape in the Middle East—both through the lens of Western representations of Muslim women, and through the more intimate subject of personal and religious conviction.

While the composition—defined by the hard edge of her black chador against the bright white background—appears sparse, measured and symmetrical, the split created by the weapon implies a more violent rupture or psychic fragmentation. A single subject, it suggests, might be host to internal contradictions alongside binaries such as tradition and modernity, East and West, beauty and violence. In the artist’s own words, “every image, every woman’s submissive gaze, suggests a far more complex and paradoxical reality behind the surface.” [1]

The Women of Allah series confronts this “paradoxical reality” through a haunting suite of black-and-white images. Each contains a set of four symbols that are associated with Western representations of the Muslim world: the veil, the gun, the text and the gaze. While these symbols have taken on a particular charge since 9/11, the series was created earlier and reflects changes that have taken place in the region since 1979, the year of the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

Islamic Revolution

Iran had been ruled by the Shah (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi), who took power in 1941 during the Second World War and reigned as King until 1979, when the Persian monarchy was overthrown by revolutionaries. His dictatorship was known for the violent repression of political and religious freedom, but also for its modernization of the country along Western cultural models. Post-war Iran was an ally of Britain and the United States, and was markedly progressive with regards to women’s rights. The Shah’s regime, however, steadily grew more restrictive, and revolutionaries eventually rose to abolish the monarchy in favor of a conservative religious government headed by Ayatollah Khomeini.

Shirin Neshat was born in 1957 in the town of Qazvin. In line with the Shah’s expansion of women’s rights, her father prioritized his daughters’ access to education, and the young artist attended a Catholic school where she learned about both Western and Iranian intellectual and cultural history. She left, however, in the mid-1970s, pursuing her studies in California as the environment in Iran grew increasingly hostile. It would be seventeen years before she returned to her homeland. When she did, she confronted a society that was completely opposed to the one that she had grown up in.

Looking back

One of the most visible signs of cultural change in Iran has been the requirement for all women to wear the veil in public. While many Muslim women find this practice empowering and affirmative of their religious identities, the veil has been coded in Western eyes as a sign of Islam’s oppression of women. This opposition is made more clear, perhaps, when one considers the simultaneity of the Islamic Revolution with women’s liberation movements in the U.S. and Europe, both developing throughout the 1970s. Neshat decided to explore this fraught symbol in her art as a way to reconcile her own conflicting feelings. In Women of Allah, initiated shortly after her return to Iran in 1991, the veil functions as both a symbol of freedom and of repression.

The veil and the gaze

The veil is intended to protect women’s bodies from becoming the sexualized object of the male gaze, but it also protects women from being seen at all. The “gaze” in this context becomes a charged signifier of sexuality, sin, shame, and power. Neshat is cognizant of feminist theories that explain how the “male gaze” is normalized in visual and popular culture: Women’s bodies are commonly paraded as objects of desire in advertising and film, available to be looked at without consequence. Many feminist artists have used the action of “gazing back” as a means to free the female body from this objectification. The gaze, here, might also reflect exotic fantasies of the East. In Orientalist painting of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for instance, Eastern women are often depicted nude, surrounded by richly colored and patterned textiles and decorations; women are envisaged amongst other beautiful objects that can be possessed. In Neshat’s images, women return the gaze, breaking free from centuries of subservience to male or European desire.

Most of the subjects in the series are photographed holding a gun, sometimes passively, as in Rebellious Silence, and sometimes threateningly, with the muzzle pointed directly towards the camera lens. With the complex ideas of the “gaze” in mind, we might reflect on the double meaning of the word “shoot,” and consider that the camera—especially during the colonial era—was used to violate women’s bodies. The gun, aside from its obvious references to control, also represents religious martyrdom, a subject about which the artist feels ambivalently, as an outsider to Iranian revolutionary culture.

Poetry

The contradictions between piety and violence, empowerment and suppression, are most prevalent in the use of calligraphic text that is applied to each photograph. Western viewers who do not read Farsi may understand the calligraphy as an aesthetic signifier, a reference to the importance of text in the long history of Islamic art. Yet, most of the texts are transcriptions of poetry and other writings by women, which express multiple viewpoints and date both before and after the Revolution. Some of the texts that Neshat has chosen are feminist in nature. However, in Rebellious Silence, the script that runs across the artist’s face is from Tahereh Saffarzadeh’s poem “Allegiance with Wakefulness” which honors the conviction and bravery of martyrdom. Reflecting the paradoxical nature of each of these themes, histories and discourses, the photograph is both melancholic and powerful—invoking the quiet and intense beauty for which Neshat’s work has become known.

As an outspoken, feminist and progressive artist, Neshat is aware that it would be dangerous to show her work in conservative modern-day Iran, and she has been living in exile in the United States since the 1990s. For audiences in the West, the “Women of Allah” series has allowed a more nuanced contemplation of common stereotypes and assumptions about Muslim women, and serves to challenge the suppression of female voices in any community.

[1] Shirin Neshat, “Artist Statement,” Signs Journal (accessed July 2015)

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Additional resources:

Pepón Osorio, En la barberia no se llora (No Crying Allowed in the Barbershop)

The Puerto Rico born artist Pepón Osorio trained as a sociologist and became a social worker in the South Bronx. His work is inspired by each of these experiences and is rooted in the spaces, experiences, and people of American Latino culture, particularly Nuyorican communities (Nuyorican refers to the Puerto Rican diaspora living in New York, especially New York City). Osorio’s large-scale installations are meant for a local audience, yet they have also been exhibited in mainstream cultural institutions (though after the 1993 Whitney Biennial, Osorio vowed to show his work first within the community, and then elsewhere).

Nuyorican

Puerto Rico is a United States territory. Its residents are United States citizens and carry an American passport, yet they cannot vote in presidential elections or have representatives voting for their interests in Washington. This sense of marginality is further complicated when one considers that Nuyoricans often retain a distinct sense of cultural pride that is informed by their dual American and Puerto Rican identities.

Having lived both experiences—that of a Puerto Rican and Nuyorican—Osorio is best known for large-scale installations that address street life, cultural clashes, and the rites of passage experienced by Puerto Ricans in the United States. Outside the traditional museum setting, and commissioned by Real Art Ways (RAW) from Hartford, Connecticut, En la barberia no se llora (No Crying Allowed in the Babershop) is a mixed-media installation located in the Puerto Rican community of Park Street in Hartford. Created in collaboration with local residents, Osorio engaged the public through conversation, workshops, and artistic collaborations. The art itself is visually lavish—his installations have often been dubbed “Nuyorican Baroque” (a reference to the seventeenth-century style characterized by theatricality and opulence and found in both Europe and Latin America).

Masculinity

Inspired from his first haircut in Santurce, Puerto Rico, Osorio recreates the space of the barbershop as one that is intensely packed with “masculine” symbols like barber chairs, car seats, sports paraphernalia, depictions of sperm and a boy’s circumcision, phallic symbols, and male action figurines. Osorio boldly challenges the idea of masculinity, and particularly of machismo (a strong sense of masculine pride), in Latino communities.

Chucherías

Spanish for trinkets or knick-knacks, and known to art historians as kitsch (mass produced objects characterized by—or ironically admired for—their bad taste), chucherías overpopulate Osorio’s work. These include Puerto Rican flags, religious ornaments, plastic toys, dolls, ribbons, beads, etc., all of which function—to quote art historian Anna Indych-Lopez—as a “gesture of cultural resistance,” presented as something universal yet personal.1 The chucherías included in the installation En la barberia no se llora, (a flag, fake foliage, baseballs, framed portraits of famous Latin American and Latino men), serve to localize the work, yet these objects also raise issues of social class expressed here through taste, and the distinction between high and low art—effectively straddling a fine line between cultural celebration and social critique.

Video

One prominent aspect of En la barberia no se llora are the video installations featuring Latino men from Park Street in stereotypically “masculine” poses. The men vary in age. Osorio included older men from the retirement home, Casa del Elderly, presenting the issue of machismo as multi-generational and deeply ingrained in Nuyorican culture. As a foil to this construction, the artist also included videos of men crying, with the public reacting both in sympathy and disgust.

These same men then participated in workshops, in which they discussed how notions of masculinity had shaped their personal relationships as brothers, husbands, and fathers. Despite this participation of men, most of the visitors to the barbershop installation were, in fact, women.[2]

While En la barberia no se llora (No Crying Allowed in the Babershop) challenges definitions of masculinity, it also brings up—in a more subtle way—the relationship between machismo and homophobia, violence, and infidelity, and the ways in which popular culture, religion, and politics help craft these identities and issues.

1. “Nuyorican Baroque: Pepón Osorio’s Chucherías,” Art Journal, vol.60, issue 1, 2001, p. 75.

2. Erika Suderburg, Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art (University of Minnesota Press, 2000), p. 323.

Tracey Emin, My Bed

A Young British Artist

In 1998 the British artist Tracey Emin spent several days languishing in bed as the result of depression. When she emerged, she decided to turn the experience into art and the result was My Bed, an installation that consisted of her unmade bed and an assortment of sundry personal items associated with her time spent there. This was not the first time Emin made art about things that many would consider excruciatingly personal. She once exhibited, as art, a package of cigarettes belonging to an uncle killed in a car crash. In 1997, she created an installation entitled Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, which was a tent appliquéd with the requisite names. Parts of My Bed were so shocking—it included soiled underwear for example—that she became a tabloid sensation.

Emin was part of a group of artists who had studied at Goldsmith College and Royal College of Art in London and were dubbed the YBAs (Young British Artists). Members of this ad hoc group, including Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Liam Gillick, and Gary Hume among others, very quickly coalesced into a movement, and began exhibiting together in warehouses and other informal spaces during the late 1980s. Hirst had organized the exhibition Freeze, widely acknowledged to have been the movement’s origin, at an abandoned space in the London Docklands in 1988.

YBA works quickly became associated with sensationalism and shock value, the impact of which was only heightened by the prevailing decade of postmodern art which, to a younger generation of artists, had increasingly become depersonalized and too reliant upon a dense theoretical framework. I remember an art school at the time in Canada issuing a call for work for a student exhibition with a list of caveats including “No hand wringing over the relationship between signifier and signified” (a reference to semiotic theory popular at the time). Everywhere it seemed a reaction to slick postmodernism was to be found in a return to a less technologically-mediated reality. The more visceral the better. Well-known YBA artworks include a calf suspended in formaldehyde (Damien Hirst), a sculpture of two fried eggs and a kebab arranged in the shape of a female body (Sarah Lucas) and of course Emin’s My Bed, which scandalized a British public with its frank portrayal of the detritus of four days of depression spent in bed.

Shock value

Shock is of course not new in art; the art-going public have been routinely scandalized at least as far back as the nineteenth century, when artists first went against accepted norms for what constitutes art. The significance of Emin’s installation, however, lies beyond its shock value. After all, shock is generally a short-lived phenomenon. Emin went on to become a nominee in 1999 for the Turner Prize, a prestigious visual arts award given annually in Britain. So what makes My Bed important as an artwork? Emin subjects to scrutiny one of the most abiding beliefs of art in Western modernism—the notion that art is always autobiographical, a reflection of the artist’s inner being.

As Western art increasingly became governed by more individualistic approaches to style and as religious and royal patronage gave way to the marketplace in the nineteenth century, the association of art with individual identity became an accepted norm. “Every painter paints himself” is a phrase known since the renaissance and it is a metaphor of this very idea that art is always an expression of the self at its core. But what does it actually mean? What aspect of self is expressed? When pressed, one is hard put to offer anything other than the most generic response: it represents emotions or feelings and perhaps a sensibility. What Emin does is take the meaning of self at its most literal sense and in the most provocative way possible. She does however present a portrait of the melancholic artist that references a tradition stretching as far back as the German renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 engraving Melencolia I, an allegorical winged female figure in a state of pensive gloom considered to be a portrait of the artist himself. But Emin’s is an unvarnished and unidealized version of depression in which glorified myths of the artist are shed in favor of a frankly visceral portrait of an artist who has spent her days in bed drinking and having sex. Emin perverts that tradition and therein lies its challenge to conventional taste.

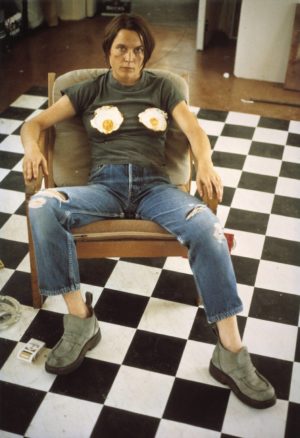

A new conceptual art

In the 1990s, as artists searched for new alternatives, many considered conceptual art of the 1970s an unfinished project. While rooted in conceptual art, postmodernism’s focus on media spectacle and consumer objects had become too tied to a market-oriented idea of the art world. Artists began revisiting the strategies of earlier artists, particularly the more visceral bodily experience that was an important aspect of conceptual art. The unflinching realness of Emin’s bed would not have been possible in the postmodern ‘80s but it certainly existed in the 1970s when artists like Chris Burden crawled through broken glass (Through the Night Softly, 1973), or had himself nailed to the front of a car (Trans-fixed, 1974).

From 1968 to 1971 Valie Export toured European cities with a structure made of styrofoam that allowed people to reach inside it and touch her breasts. The artist Vito Acconci had himself blindfolded in the basement of a gallery, and armed with metal pipes and a crowbar, would threaten to swing at anyone who came near (Claim, 1971). Challenging conventional ideas around artistic creativity, as these artists did, is, in fact, a venerable tradition in modern and contemporary art. Artists continually renew the conditions and parameters of what constitutes art or artistic authorship.

Much like conceptual artists who rejected the medium of painting as too conventional in favor of newer and more experimental forms and ideas, Emin had abandoned painting and even went so far as to destroy many of them. In a famous argument with artist and boyfriend Billy Childish, she referred to his paintings as “stuck” in time. In response, Childish formed a movement called “Stuckism” which promoted painting and creative expression while denouncing Emin’s brand of conceptual art. “Stuckism” would prove to be short-lived, but Emin’s My Bed would become one of the most resonant works of the 1990s.

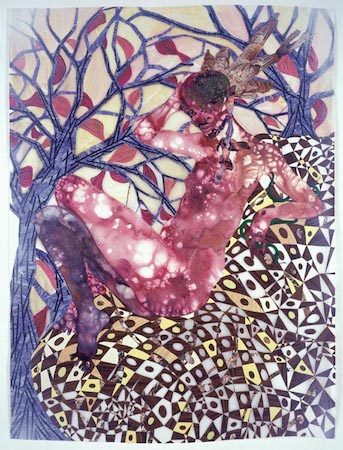

Kiki Smith, Lying with the Wolf

This delicate but large-scale work on paper, which depicts a female nude reclining intimately alongside a wolf, represents the assimilation of several themes that Kiki Smith has explored throughout her decades-long career. Featuring an act of bonding between human and animal, the piece speaks not only to Smith’s fascination with and reverence for the natural world, but also her noted interests in religious narratives and mythology, the history of figuration in western art, and contemporary notions of feminine domesticity, spiritual yearning, and sexual identity.

Lying with the Wolf is one in a short series of works executed between 2000 and 2002 that illustrates women’s relationships with animals, drawing from representations found in visual, literary, and oral histories. Smith is most interested in narratives that speak to collectively shared mythologies; these include folk tales, biblical stories and Victorian literature, yet the once-familiar stories are then fragmented and conflated with one another to form new clusters of meaning and association.

Intimate Relationships with Nature

Many of Smith’s works from this period feature a female protagonist who is based on Little Red Riding Hood as well Sainte Geneviève, the Patron Saint of Paris. Geneviève is herself often associated with Saint Francis of Assisi because of her close relationships with animals and her ability, in particular, to domesticate wolves.

Other works in the series include Geneviève and the May Wolf—a bronze sculpture in which a standing female figure calmly embraces the wolf—and Rapture, which is perhaps more closely aligned to Red Riding Hood, as it depicts a woman stepping out from the stomach of the recumbent creature.

The pair as depicted in Lying with the Wolf, however, seems locked in a more intimate embrace, as the wolf nuzzles affectionately into the nude woman’s arms. She wraps herself around the animal’s body in a gesture of comforting, her fingers stroking the soft fur beneath its ears and along the side of its stomach. The wolf’s wildness is tamed, and both figures seem to nurture one another, floating within the abstract space of the textured paper surface upon which they are delicately drawn. Smith imbues a story that is normally quite violent with a kind of tenderness that is characteristic of her overall aesthetic.

Feminist Approaches to Narrative

It has been suggested by some critics that Smith’s reinterpretations of Red Riding Hood and Sainte Geneviève represent a feminist approach to popular folktales. This is supported by her placement of “woman” amidst the natural world, but also, importantly, at a structural level: in the way in which the two narratives are fragmented and combined. Borrowing from divergent sources in order to forge a new storyline, Smith demonstrates the slippery relationship between a visual image and its multiple references, adopting a narrative style indebted to feminist re-writings of history.

As the curator Helaine Posner has explained: “Instead of presenting them in their traditional roles as predator and prey, Smith re-imagined these characters as companions, equals in purpose and scale.” The distinction between “predator” and “prey” might be thought of as a metaphor for hierarchies of power in human relationships, which have traditionally been drawn along the lines of gender, race, and class. Because patriarchal societies typically grant more power to men, while requiring women to be submissive or dependent, we can think of this “overturning” in Smith’s art as a political statement against such inequalities. The artistic narratives portrayed in her work are ones in which binaries are flipped and opposing qualities are merged; in so doing, Smith asserts a critical feminist position that favors the articulation of multiple meanings.

“Walking Around in a Garden”

“My career has stopped being linear. A couple of years ago, the story line or narrative fell apart…”1

As is the case with Lying with the Wolf, several of Smith’s works integrate a diverse list of themes and motifs that she has accumulated over the course of her career. The artist continuously re-imagines tropes she has used in past works, with the result that her practice does not seem to progress through discrete artistic stages. Rather, she works in cycles and layers; she has described her career as an act of meandering, or “walking around in a garden.”

Kiki Smith grew up in a vibrant artistic family; she is the daughter of the sculptor Tony Smith and the opera singer Jane Lawrence Smith. She has spoken fondly of the Victorian house in which she was raised in South Orange, New Jersey, and how it captured her young imagination, as a historical artifact with its own memories and indices to the past. The notion of “home” has been central to her practice, and she likens it to the human body, a theme that is pervasive across her oeuvre. Domesticity, fragility, and the humble materials of craft and folk arts feature strongly in her work.

Abjection and The Body

While Kiki Smith’s early work is aligned with the collaborative and activist art scene of the 1980s, she became known for intimate explorations of the human body in the following decade, often through life-sized sculpture that honored the figural tradition in Western art.

These works emphasized the body’s vulnerability and made reference to feminist theories of the “abject,” which conceived of the body as a messy, porous, and boundary-less system. Blood Pool, for instance, features a small, apparently violated figure, huddled into a fetal position on the floor . Many other works of this period feature bodily fluids or marks of injury.

Mysticism and Mythologies

Throughout the 1990s, Smith would come to embrace her religious upbringing, creating works that are spiritual, ethereal, and markedly more decorative. Celestial motifs and references to the natural world became ubiquitous, although these themes are still deeply connected to the body. As an investigation of the body in its capacity for fertility, reproduction, and nurturing, this turn towards the natural environment would eventually lead Smith to her interest in animals and our connections to them.

Lying with the Wolf is an extension of this yearning to connect the earthly with the spiritual and the personal with the collective.

1. As quoted in Christopher Lyon, “Free Fall: Kiki Smith on Her Art” in Kiki Smith, ed. Helaine Posner and Christopher Lyon, New York, NY: The Monacelli Press, Inc: page 37.

Wangechi Mutu, Preying Mantra

Using the medium of collage, the artist Wangechi Mutu creates new worlds that re-imagine culture through the realm of fantasy. Mutu was born in Nairobi, Kenya and educated in Europe and the United States. Her art is global in nature and she clearly relishes complicating both Western and non-Western cultural norms, questioning how we see gender, sexuality, and even cultural identity.

Wangechi Mutu’s artistic practice includes video, installation, sculpture, and mixed-media collage. One of her recurrent themes concerns the violence of colonial domination in Africa (particularly in her native Kenya). Her images incorporate the female body, specifically an imagined “African” body, subjected to sexism and racism on a global scale.

Sources for Mutu’s collages include fragments from fashion magazines, pornography, medical literature or even popular magazines such as National Geographic. Inspiration for her collages can be traced to the early photomontages of the German Dada artist Hannah Höch (below left) and the American artist Romare Bearden (below right). Mutu appreciates Bearden’s use of collage—how it emphasizes community and the African American traditions found in jazz, while the spliced images in Höch’s photomontages reflect Mutu’s interest in disrupting societal convention in art. Mutu creates a space for exploring an informed consciousness about being “African” and female that incorporate these artists’ techniques yet develops a new visual vocabulary.

Preying Mantra centers on female subjectivity, exoticism and the notion of hybridity—both in concept and imagery. Hybridity is a concept often used in postcolonial studies. It describes how mixing the cultures of colonized and the colonizer can produce a third space for newer and often disruptive understanding of cultural identity. Colonialism in Africa, which began in earnest in the nineteenth century, violently wrested power from Africans for the benefit of European nations through the enforcement of strict military and administrative controls. As colonialism waned during the mid-twentieth century, other social and political issues emerged. Mutu’s work was shaped by this complex history and by issues such as the rights of women that came to the fore at the end of the century.

In Mutu’s Preying Mantra, a female creature appears to recline on a geometrically patterned blanket that is sprawled between trees or perhaps on a tree branch. The blanket resembles a Kuba cloth (traditional fabric created by the Kuba people). Legs tightly crossed in front of her, the figure stares suggestively at the viewer with her right hand positioned behind her head, which is surmounted by a cone-like crown. Her relaxed posture is camouflaged by her skin, which appears dappled by sunlight and which mirrors the colors of the tree’s leaves. Like the female body, the tree is emblematic of the creation myths found in many cultures, including Mutu’s Kikuyu ancestors in Kenya. In her left hand, the figure holds a green serpent that rests on the blanket which fills much of the scene. The serpent, linked with the role of Eve in the biblical creation narrative, provides yet another cultural source for Mutu’s protagonist. The tree envelops the female figure, reinforcing links between history and fiction, African and Non-African cultural myths as well as natural versus unnatural phenomena.

The title Preying Mantra, recalls the praying mantis—an insect that resembles the protagonist in Mutu’s collage, with her prominently bent legs. As a carnivorous insect, praying mantises camouflage themselves to match their environment, snaring their prey with their enormous legs. During mating, the female can become a sexual cannibal—eating her submissive mate. Such imagery and its association with natural phenomena creates a primal sensibility. Despite this reference to a real praying mantis, Mutu’s “preying mantra” is also vulnerable to our gaze, suggesting that the figure may be a victim that is “preyed” upon by “mantras.” Mutu creates a natural, even primitive, fictional environment that entices and disturbs us even as she invites us to explore stereotypes about the African female body as explicitly sexual, dangerous, and aesthetically deformed in relation to Western standards. Given that elements of the collage are assembled from sociocultural documents found in popular literature from the West, the figure may be preying on the viewer’s own fears and desires.

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Additional resources:

This work at the Brooklyn Museum

Wangechi Mutu on Failure (Art21 Magazine)

Artist Breakfast With Wangechi Mutu (artnet video)

Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey (video from the Brooklyn Museum)

Trevor Schoonmaker, Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey (North Carolina: Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 2013)

Turning Uncle Tom’s Cabin upside down, Alison Saar’s Topsy

by DR. HALONA NORTON-WESTBROOK, TOLEDO MUSEUM OF ART and DR. BETH HARRIS

Jason and the Golden Fleece and the American anti-Slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin combine to upend our own contemporary myths