3.1: Introduction, Twentieth-Century Modernism

- Page ID

- 107362

Crisis of Reference and Representation

By Sarah Churchill

The early twentieth century was riddled with contradictions. While a time of great technological change, utopian aspirations, scientific breakthroughs and improvements in living standards for the working classes, the period also saw economic disaster, a global influenza pandemic (1918–20) and devastating technological warfare that killed millions and wounded scores more. The two World Wars, along with technological and political change, utterly remade Europe in the interwar period. Many faced the consequences with great uncertainty, though some wholly embraced the chaos as "cleansing" the present from the force of the past. America, conversely, which joined World War I (1914–18) late in 1917, suffered far fewer deaths and no damage to its infrastructure, entered the 1920s with a newfound confidence. This proud self-assurance, however, was sorely tested during the Great Depression, when as many as six million Americans found themselves unemployed and dependent upon charity, government assistance and long bread lines.

Abstraction rolled out unevenly and in all directions in the early twentieth century, absorbing local culture and influences and responding to regional concerns. The loss or dissolution of figuration offered a new means of expression to those attempting to negotiate the social crisis wrought by the processes of modernity. Yet figurative art remained a potent force, particularly in America, where European modernism came late, and in Soviet Russia, where Soviet Realism depicted idealized communist values. While illusionism largely went out of vogue in the period, it remained part of the visual vocabulary from which artists worked and sometimes worked against.

Utopianism

In Looking Backward (1888), a utopian fiction written by Edward Bellamy, a young man named Julian West falls into a deep sleep and awakens in the year 2000 to find a socialist utopia freed from want and greed in which men and women work in dignity and harmony. Such ideas permeated the early twentieth century, as globally citizens reckoned with the forces of a mechanized, industrial revolution and indulged in fantasies of the natural progression of mankind towards something better and greater. Artists and philosophers alike questioned how human beings might live, and live better, as machines increasingly took over aspects of human labor, a question that continues to plague us even today.

The term "utopia" comes from two ancient Greek words: "utopia," meaning "no place," and "eutopia," meaning "good place." The first recorded utopian writing was Plato's Republic written in the late fourth century BCE. Other important works of utopian fiction include Thomas Moore's Utopia, published during the High Renaissance in 1516 and William Morris's News From Nowhere (1890). Utopian philosophy and social engineering was particularly popular in the late-nineteenth century in Britain and America, where concerns over industrialization and religious fears about the "end of times" motivated the formation of communes like Oneida in New York and the phalanstères of Charles Fourier.

Notably, utopian thought experiments were as likely to enslave as they were to liberate. As Margaret Atwood famously wrote in her iconic dystopian novel The Handmaid's Tale, “Better never means better for everyone... It always means worse, for some.” Some, like the Futurists, saw war and technology as the answer to a better life. In architecture, International Modernists like Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius imagined that one could design better living through advanced architectural engineering. Politically, utopianism also had a darker and more dystopian side as the rise of National Socialism in Germany and Fascism in Italy and Spain illustrates. Yet, these political movements have obscured somewhat the imaginative potential of utopias in the production of modern culture. As the German philosopher Ernst Bloch explains, utopian imagination in practice functions as a space wherein “anticipatory consciousness” develops and inspires a transformative, future-oriented agency. Utopias, for Bloch, were not a blueprint to be executed, but were rather a means of "educating" and nurturing hope for a better and more just world.

Sources: Bloch, Ernst. The Principle of Hope: Volume 1, Trans. Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice and Paul Knight (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1952/1995)

Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid's Tale (1985)

Formalism II: Truth to Materials

by Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant

“Formalism” is the name given to a theory that locates the nature and purpose of art in its sensory, material properties or form. For the visual arts, this includes line, shape, color, composition, texture, and so on. In Formalism I we examine a branch of formalist art theory that sees the purpose of art as evoking specifically aesthetic feelings, such as beauty or harmony. Here, we turn to a later development of formalism that called for “truth to materials.”

Truth to materials

In this branch of formalist art theory, the primary focus remains on the material qualities of the artwork, but instead of asserting that the artist’s goal is formal harmony, some artists and critics begin to talk about art as a means of understanding and displaying the properties of the materials of which it is made.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Pluto and Proserpina, 1621-22, marble (Galleria Borghese, Rome, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Ever since the Renaissance, artists in pursuit of naturalism had attempted to transcend the limitations of their media. Sculptors such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini excelled at making hard, cold marble look like soft flesh and fluttering drapery.

Henry Moore, Reclining Woman, 1930, green Hornton stone, 59.7 x 92.7 x 41.3 cm (National Gallery of Canada, photo: Gbuchana, CC0)

Certain artists in the twentieth century, by contrast, chose to showcase rather than disguise their materials. In 1934, British sculptor Henry Moore put it this way: “Every material has its own individual qualities … Stone, for example, is hard and concentrated and should not be falsified to look like soft flesh … It should keep its hard tense stoniness.” [1] This imperative to be ‘true to one’s materials’ became an important critical tenet of twentieth-century art.

There are nineteenth-century roots to this idea, especially in architecture and design theory. The Victorian art critic John Ruskin made it an imperative for artists and craftspeople to “honor” their materials:

The workman has not done his duty, and is not working on safe principles, unless he … honours the materials with which he is working … If he is working in marble, he should insist upon and exhibit its transparency and solidity; if in iron, its strength and tenacity; if in gold, its ductility …[2]

In part, this insistence on truth to materials arose in the nineteenth century because of the proliferation of low-quality, mass-produced manufactured goods. In furniture and interior decoration, cheap materials were often disguised to make them look more expensive, such as faux marbling, wood veneers, or imitation copper patina. Ruskin called such falsified use of materials “illegitimate and debased,” [3] terms that reflect a moral imperative to use materials honestly.

Constructivism and the Bauhaus

The formalist principle of “truth to materials” was taken up in the second and third decades of the twentieth century by art and design movements such as Constructivism and the Bauhaus.

Vladimir Tatlin. Counter-Relief, 1913, wood, metal, leather (The State Tretyakov Gallery)

In this Russian Constructivist sculpture by Vladimir Tatlin, the materials themselves are the primary focus of the artist. An old wood panel is used as a tack board for scraps of found materials: leather, wire, stamped tin, a wooden dowel, and offcuts of copper sheet. Each of these materials has been manipulated in ways that show off its properties: the wood is pitted and weathered, the coarse-grained leather is stretched tautly between brass tacks, the copper sheet has been cut and bent into sharp, edgy planes, and the wire has been curled into tight spirals. There is no moral lesson or symbolism here; it is simply a sampler of materials displayed in ways that demonstrate their material properties.

Josef Albers giving a critique of student exercises in his introductory class, 1928

Influenced by ideas coming out of Russia, the German design school Bauhaus instituted a rigorous introductory course to familiarize students with basic design principles and the properties of various materials. A typical exercise in Josef Albers’ class would help students to understand the qualities of paper through open-ended, independent experimentation, “a playful tinkering with the material for its own sake.” [4] In the resultant student projects, we can see folds, rolls, cuts, tears, corrugation, notching — all sorts of ways of working with paper to develop an understanding of its nature and potential as a constructive medium.

Greenbergian formalism

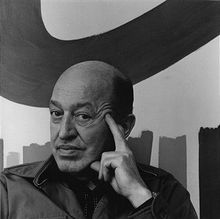

Clement Greenberg in 1972

In the mid-twentieth century, the influential American art critic Clement Greenberg consolidated the entire history of modern art around this idea of truth to materials. Attempting to account for what, if anything, such diverse-seeming styles as Impressionism, Cubism, Constructivism, and Abstract Expressionism had in common, Greenberg concluded that all modern artists were attempting to be true to their materials, and more specifically to “purify” their respective media.

For Greenberg, each artistic medium, such as painting, sculpture, or literature, has an “area of competence” that it should stick to, as determined by its material properties:

It quickly emerged that the unique and proper area of competence of each art coincided with all that was unique to the nature of its medium. The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of any other art. Thereby each art would be rendered ‘pure’…[5]

Literature is a temporal medium

For example, literature is a temporal medium, since it is read sequentially, word-by-word and page-by-page. Hence story-telling, the development of events and characters through time, is within its area of competence.

A painting, by contrast, can only with great difficulty tell stories; it struggles to show more than a single moment in a single action. Hence narrative is not really part of painting’s area of competence. The whole category of “history painting” (art depicting stories from history, literature, or mythology) is counter to what Greenberg believed was the true vocation of painting.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1785, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25m, (Musée du Louvre)

In addition, it is only with great difficulty that painting shows a third dimension. By using techniques such as chiaroscuro to suggest volume and perspective to suggest space, artists can give an illusion of a third dimension — but it is only an illusion, and it falsifies painting’s true nature. Volume is properly within sculpture’s area of competence, and space is within architecture’s.

For Greenberg, painting’s area of competence lies in three factors: the flatness of the surface, the shape of the support (typically a rectangular canvas), and the properties of the pigment or color that is put upon that surface. Of these three, Greenberg argued, the most unique to painting is flatness; consequently, he saw the entire history of modern painting as a gradual embrace of painting’s flatness.

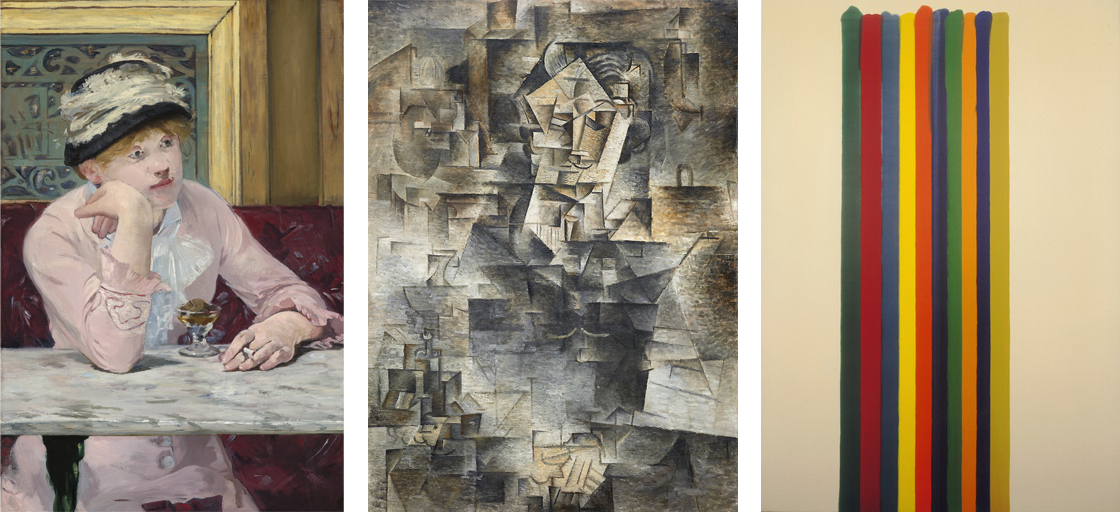

Left: Edouard Manet, The Plum, 1877, oil on canvas, 73.6 x 50.2 cm (National Gallery, Washington DC); center: Pablo Picasso, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, oil on canvas, 39 9/16 x 26 9/16 inches (Art Institute of Chicago); right: Morris Louis, Number 4-31, 1962, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 210.2 x 147.6 cm (MoMA)

In Greenberg’s view, modernist painting began with Edouard Manet’s compression of space and use of a frontal light source that minimized chiaroscuro and denied the illusion of mass. Cubism continued this development, its slightly-angled facets, spread across the entire surface of the painting, defining only a very shallow space. The mid-century American modernists of Greenberg’s own time finally embraced the true identity of painting as a flat surface covered with a colored design.

Backlash

Greenberg had enormous influence on art in the mid-twentieth century, as some artists attempted to fulfill his exacting criteria for formalist purity. Today, however, Greenberg’s rigorous version of formalist art theory is almost completely discredited. Socially-conscious artists, critics, and art historians object to the way the formalist theory of art separates art from its social context. History, politics, spirituality, expression — all of these are irrelevant to the formalist theory of art.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, oil on canvas, 349 cm × 776 cm. (Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid)

One could do an exclusively formalist reading of Picasso’s Guernica, and consider how the artist tastefully contrasted organic, curving shapes with hard-edged, angular shapes; or discuss how he rejected perspective and minimized modeling to assert the flatness of the painting’s surface. However, to do so would be to ignore the clear desperation of the gesticulating characters, the horror of the event, the classical references, the powerful expression, and above all the urgent political message.

Formalism as a totalizing theory of art the way Clive Bell or Clement Greenberg imagined is largely an historical footnote. However, it is an important footnote, and ideas of formal harmony and truth to materials had a great deal of influence for many nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists. It is just as impossible to fully understand the history of modern art without acknowledging formalism, as it is to understand modern art using only formalism.

It is also important not to confuse the theory of formalism with the technique of formal analysis. With rare exceptions, works of art have a physical presence and formal properties that are integral to what they have to say, and we need to have a keen eye to discern those properties and describe how they affect the work’s meaning(s). While formalism may be dead, formal analysis remains an essential skill for the study of art.

Notes:

- Henry Moore, “Statement for Unit One,” in Herbert Read, ed., Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture (London, 1934), p. 29.

- John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, vol. 2 (London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 1953), appendix 12: Modern Painting on Glass, pp. 391-92.

- Ibid.

- Josef Albers, “Teaching Form through Practice,” Bauhaus vol. 2 no. 3 (1928), translated by Frederick Amrine, Frederick Horowitz, and Nathan Horowitz, 2005, http://albersfoundation.org/teaching...-albers/texts/ (accessed 13 February 2020).

- Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting” (1960), in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory, 1900-1990 (Oxford, U.K. and Cambridge, MA, 1997), p. 755

Additional resources:

Learning with Itten at the Getty Museum

Cite this page as: Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, "Formalism II: Truth to Materials," in Smarthistory, April 3, 2020, accessed July 5, 2021, https://smarthistory.org/formalism-ii-truth-to-materials/.

Representation and abstraction: looking at Millais and Newman

by SAL KHAN, DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Vir Heroicus Sublimus, 1950-51 (MoMA)

What’s “heroic” about a painting that looks like a craft project on HGTV? This comparison suggests an answer.

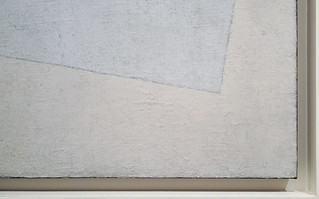

Art and context: Monet’s Cliff Walk at Pourville and Malevich’s White on White

by SAL KHAN, DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Claude Monet, Cliff Walk at Pourville, 1882, oil on canvas, 26-1/8 x 32-7/16 inches (66.5 x 82.3 cm) (Art Institute of Chicago), and Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918, oil on canvas, 31 1/4 x 31 1/4″ (79.4 x 79.4 cm) (MoMA)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: