2.7: Post-Impressionism

- Page ID

- 107395

Post-Impressionism

Cézanne, Seurat, Van Gogh, and Gauguin are all Post-Impressionists, though their styles vary widely.

c. 1880 - 1900

A beginner's guide

Introduction to Neo-Impressionism, Part I

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Just a dozen years after the debut of Impressionism, the art critic Félix Fénéon christened Georges Seurat as the leader of a new group of “Neo-Impressionists.” He did not mean to suggest the revival of a defunct style — Impressionism was still going strong in the mid-1880s — but rather a significant modification of Impressionist techniques that demanded a new label.

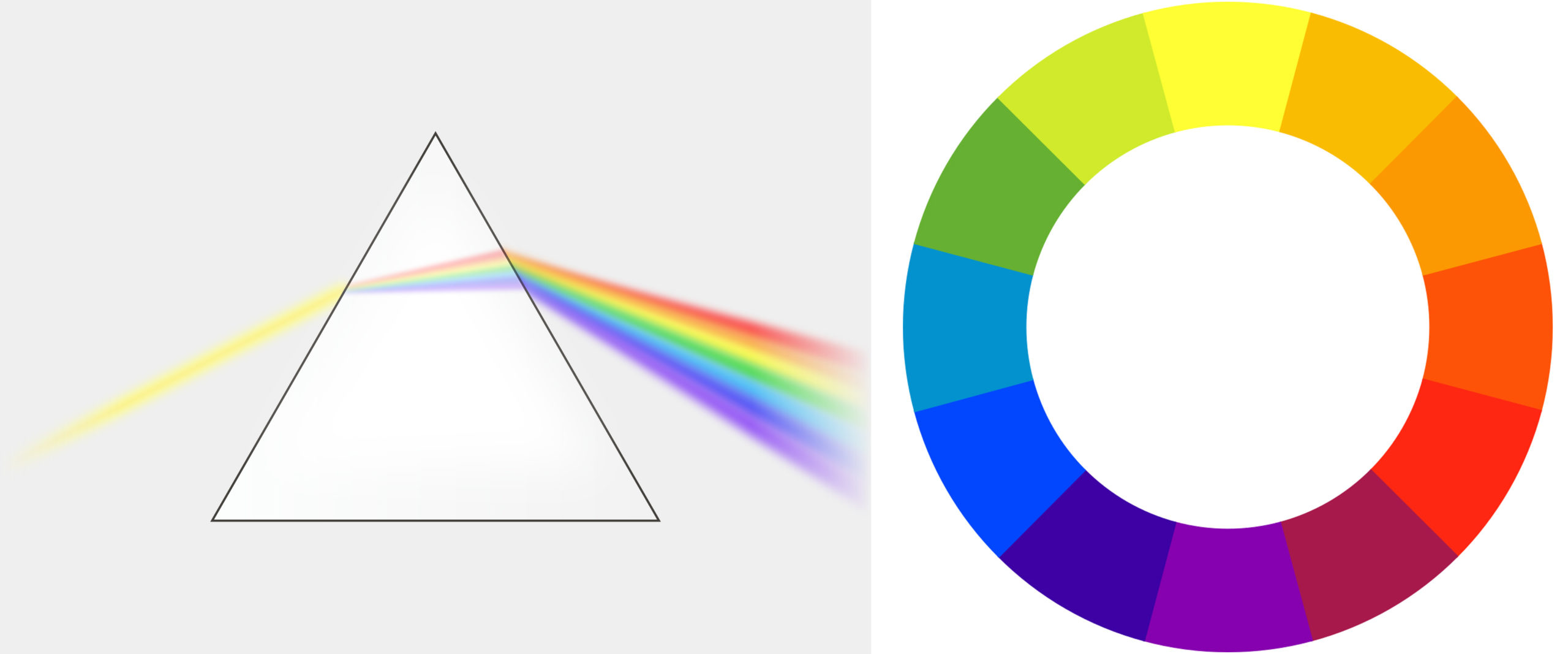

Fénéon identified greater scientific rigor as the key difference between Neo-Impressionism and its predecessor. Where the Impressionists were “arbitrary” in their techniques, the Neo-Impressionists had developed a “conscious and scientific” method through a careful study of contemporary color theorists such as Michel Chevreul and Ogden Rood. [1]

A scientific method

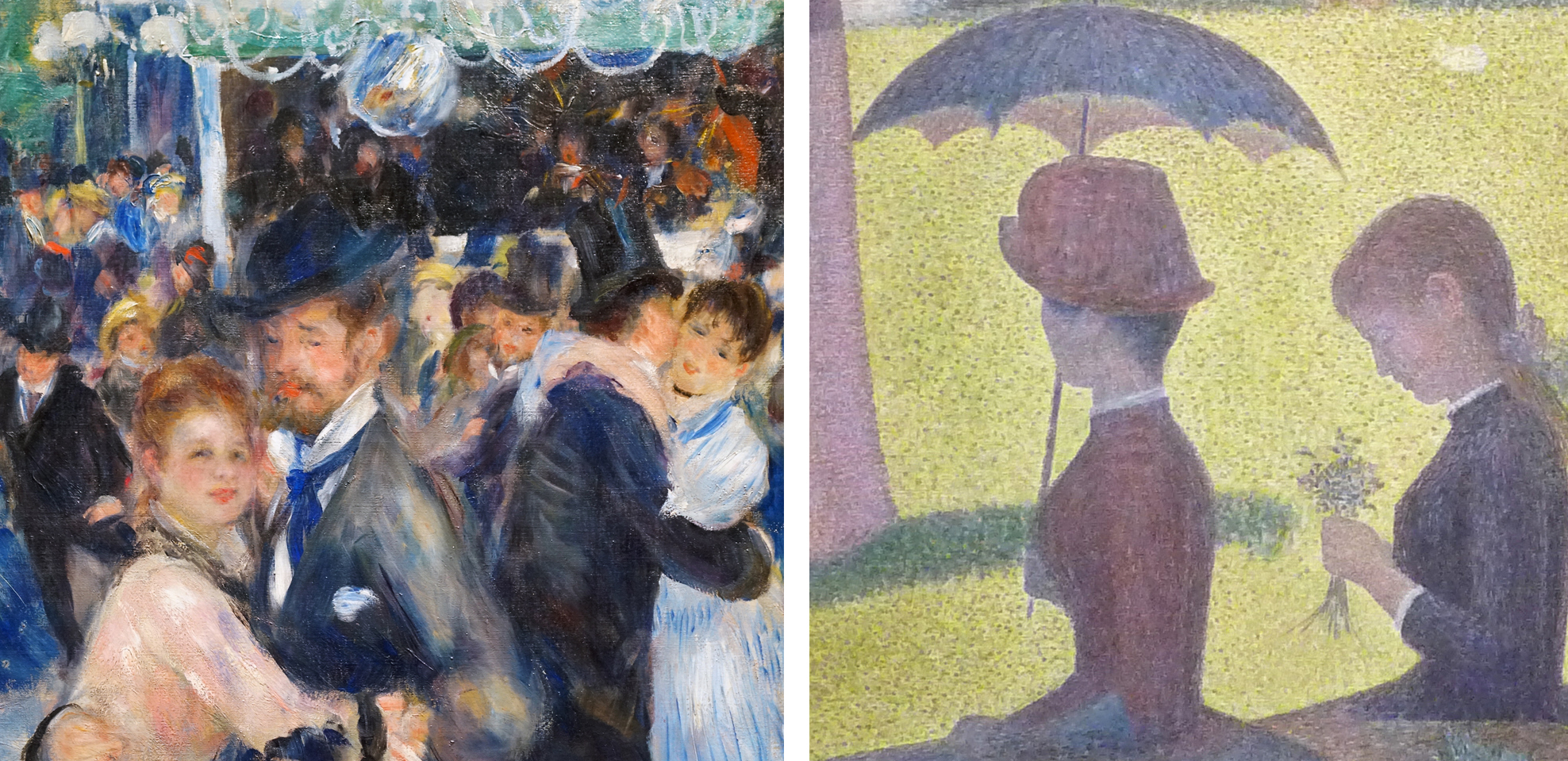

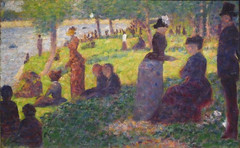

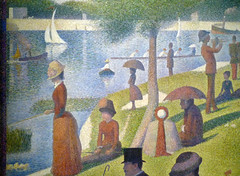

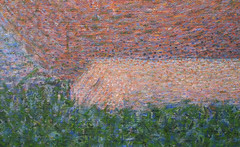

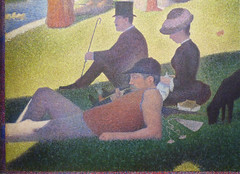

This greater scientific rigor is immediately visible if we compare Seurat’s Neo-Impressionist Grande Jatte with Renoir’s Impressionist Moulin de la Galette. The subject matter is similar: an outdoor scene of people at leisure, lounging in a park by a river or dancing and drinking on a café terrace. The overall goal is similar as well. Both artists are trying to capture the effect of dappled light on a sunny afternoon. However, Renoir’s scene appears to have been composed and painted spontaneously, with the figures captured in mid-gesture. Renoir’s loose, painterly technique reinforces this effect, giving the impression that the scene was painted quickly, before the light changed.

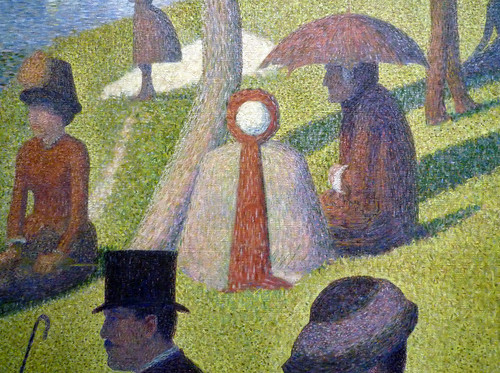

By contrast, the figures in La Grande Jatte are preternaturally still, and the brushwork has also been systematized into a painstaking mosaic of tiny dots and dashes, unlike Renoir’s haphazard strokes and smears. Neo-Impressionist painters employed rules and a method, unlike the Impressionists, who tended to rely on “instinct and the inspiration of the moment.” [2]

Pointillism and optical mixture

One of these rules was to use only the “pure” colors of the spectrum: violet, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red. These colors could be mixed only with white or with a color adjacent on the color wheel (called “analogous colors”), for example to make lighter, yellower greens or darker, redder violets. Above all, the Neo-Impressionists would not mix colors opposite on the color wheel (“complementary colors”), because doing so results in muddy browns and dull grays.

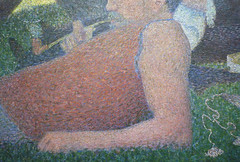

More subtle color variations were produced by “optical mixture” rather than mixing paint on the palette. For example, examine the grass in the sun. Seurat intersperses the overall field of yellow greens with flecks of warm cream, olive greens, and yellow ochre (actually discolored chrome yellow). Viewed from a distance these flecks blend together to help lighten and warm the green, as we would expect when grass is struck by the yellow-orange light of the afternoon sun. It was this technique of painting in tiny dots (“points” in French) that gave Neo-Impressionism the popular nickname”Pointillism” although the artists generally avoided that term since it suggested a stylistic gimmick.

For the grass in the shadows, Seurat uses darker greens intermixed with flecks of pure blue and even some orange and maroon. These are very unexpected colors for grass, but when we stand back the colors blend optically, resulting in a cooler, darker, and duller green in the shadows. This green is, however, more vibrant than if Seurat had mixed those colors on the palette and applied them in a uniform swath.

Similarly, look at the number of colors that make up the little girl’s legs! They include not only the expected pinks and oranges of Caucasian flesh, but also creams, blues, maroons, and even greens. Stand back again, though, and “optical mixture” blends them into a convincing and luminous flesh color, modeled in warm light and shaded by her white dress. (For more technical information on this topic, see Neo-Impressionist color theory).

Compositional rigor

The Neo-Impressionists also applied scientific rigor to composition and design. Seurat’s friend and fellow painter Paul Signac asserted,

The Neo-Impressionist … will not begin a canvas before he has determined the layout … Guided by tradition and science, he will … adopt the lines (directions and angles), the chiaroscuro (tones), [and] the colors (tints) to the expression he wishes to make dominant.Paul Signac, Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, in Nochlin, ed., p. 121.

Numerous studies for La Grande Jatte testify to how carefully Seurat decided on each figure’s pose and arranged them to create a rhythmic recession into the background. This practice is very different from the Impressionists, who emphasized momentary views (impressions) by creating intentionally haphazard-seeming compositions, such as Renoir’s Moulin de la Galette.

Seurat’s Parade de cirque is even more rigorously geometrical. It is dominated by horizontal and vertical lines, and the just slightly off-rhythmic spacing of the figures and architectural structure creates a syncopated grid. Scholars have debated whether the composition is based on the Golden Section, a geometric ratio that was identified by ancient Greek mathematicians as being inherently harmonious.

Systematized expression

The Neo-Impressionists also attempted to systematize the emotional qualities conveyed by their paintings. Seurat defined three main expressive tools at the painter’s disposal: color (the hues of the spectrum, from warm to cool), tone (the value of those colors, from light to dark), and line (horizontal, vertical, ascending, or descending). Each has a specific emotional effect:

Gaiety of tone is given by the dominance of light; of color, by the dominance of warmth; of line, by lines above the horizontal. Calmness of tone is given by an equivalence of light and dark; of color by an equivalence of warm and cold; and of line, by horizontals. Sadness of tone is given by the dominance of dark; of color, by the dominance of cold colors; and of line, by downward directions.

Georges Seurat, Letter to Maurice Beaubourg, August 28, 1890, in Nochlin, ed., p. 114 (translation modified for clarity).

Seurat’s Chahut (Can-Can) seems designed to exemplify these rules, employing mostly warm, light colors and ascending lines to convey a mood of gaiety appropriate to the dance.

The Neo-Impressionist style had a relatively brief heyday; very few artists carried on the project into the 20th century. However, a great many artists experimented with it and took portions of its method into their own practice, from van Gogh to Henri Matisse. More broadly, the Neo-Impressionist desire to conform art-making to universal laws of perception, color, and expression echoes throughout Modernism, in movements as diverse as Symbolism, Purism, De Stijl, and the Bauhaus.

So far we have concentrated on the style of Neo-Impressionism. In Part 2, we will examine the subject matter favored by the artists, and discuss its relation to the social and political context of the late-nineteenth century.

Notes:

- Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes en 1886,” as translated in Linda Nochlin, ed., Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 1874-1904: Sources and Documents (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966), p. 108.

- Paul Signac, From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism (1899), as translated in Nochlin, ed., p. 122.

Introduction to Neo-Impressionism, Part II

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

In Part 1 of this introduction to Neo-Impressionism we examine the style of the movement, concentrating on the artists’ attempt to systematize a method for painting according to scientific laws of perception, color, composition, and expression. Here, we will turn to the kind of subject matter typically chosen by the Neo-Impressionists and discuss its relation to late-nineteenth century social and political history.

Scenes of leisure

For the most part, the Neo-Impressionists continued to depict the kinds of subjects preferred by the Impressionists: landscapes and leisure scenes. In addition to his famous painting of people lounging in the park on the island of La Grande Jatte, many of Georges Seurat’s paintings portrayed entertainments such as the circuses and music halls that contributed to Paris’s reputation for mass spectacles in the late nineteenth century.

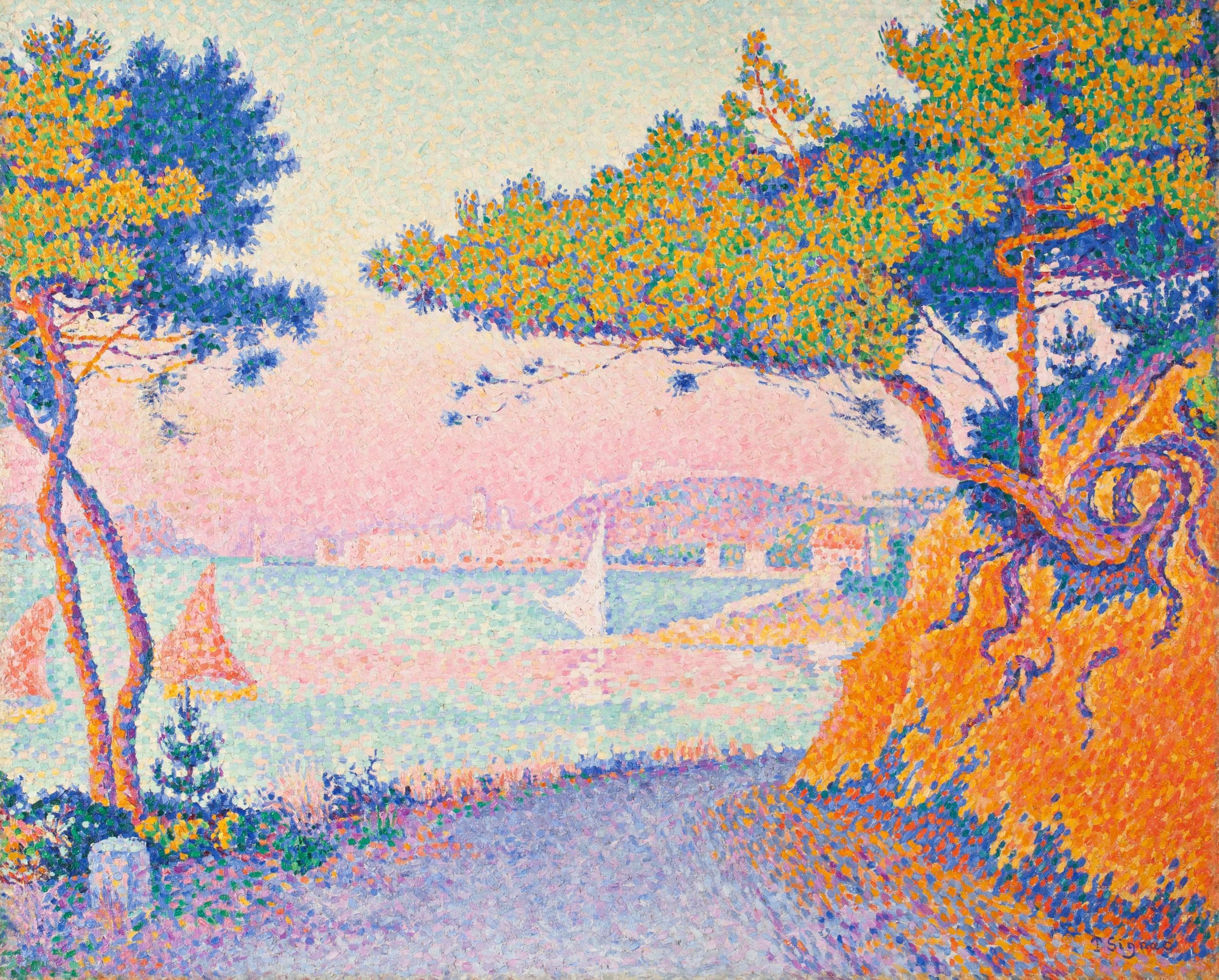

Paul Signac’s landscape paintings similarly reveal a concentration on leisure scenes. A sailor himself, Signac painted dozens of harbor scenes dominated by the sails and masts of small pleasure craft. The Mediterranean coast of France, where Signac spent his summers, had a reputation both for the quality of its light — a key interest of the Neo-Impressionists generally — and for a laid-back, sun-filled lifestyle. In Signac’s canvases, the bright colors favored by the Neo-Impressionists perfectly complement this reputation.

Social inequality

Although these subjects suggest carefree pleasure, there are undertones of social criticism in some Neo-Impressionist paintings. Seurat’s Circus shows the strict class distinctions in Paris both by location, with the wealthier patrons seated in the lower tiers, and by dress and posture, which gets markedly more casual the further the spectators are from ringside.

One contemporary critic also remarked that the rigidity of the poses in Seurat’s La Grande Jatte reminded him of “the stiffness of Parisian leisure, prim and exhausted, where even recreation is a matter of striking poses.” [1] As we examine the characters in La Grande Jatte in detail, there are some surprising inclusions and juxtapositions. In the left foreground, a working-class man in shirtsleeves overlaps a much more formally-dressed middle-class gentleman in a top hat holding a cane. A trumpet player in the middle-ground plays directly into the ears of two soldiers standing at attention in the background. A woman with an ostentatiously eccentric pet monkey on the right and another fishing on the left have been interpreted as prostitutes, one of whom is casting out lures for clients. Between them, a toy lap-dog with a pink ribbon leaps toward a rangy hound whose coat is as black as that of the bourgeois gentleman with the cane.

Despite these provocative juxtapositions and overlaps, very few of the figures actually seem to be interacting with each other; each is lost in their own world. Unlike the mood of convivial good-fellowship between the classes and sexes in Auguste Renoir’s Moulin de la Galette, Seurat’s Grande Jatte sets up a dynamic of alienation and tension.

La Grande Jatte forms an implicit pair with an earlier painting of the same size by Seurat, Bathers at Asnières. Asnières was an industrial suburb of Paris, just across the river Seine from La Grande Jatte. Unlike that island’s largely middle-class patrons in their top hats and bustle skirts, here we see more working-class and lower-middle-class figures in shirtsleeves and straw hats or bowlers. In the background the smokestacks of the factories at Clichy serve as a reminder of labor, even during the men’s leisure time.

As in the painting of La Grande Jatte, all of the figures are isolated in their own world, but a sense of implicit tension is raised by their insistent gaze across the river at their wealthier compatriots. A middle-class couple being rowed by a hired oarsman in a boat with a prominent French flag further adds to the class tensions raised by the work.

Political revolutionaries?

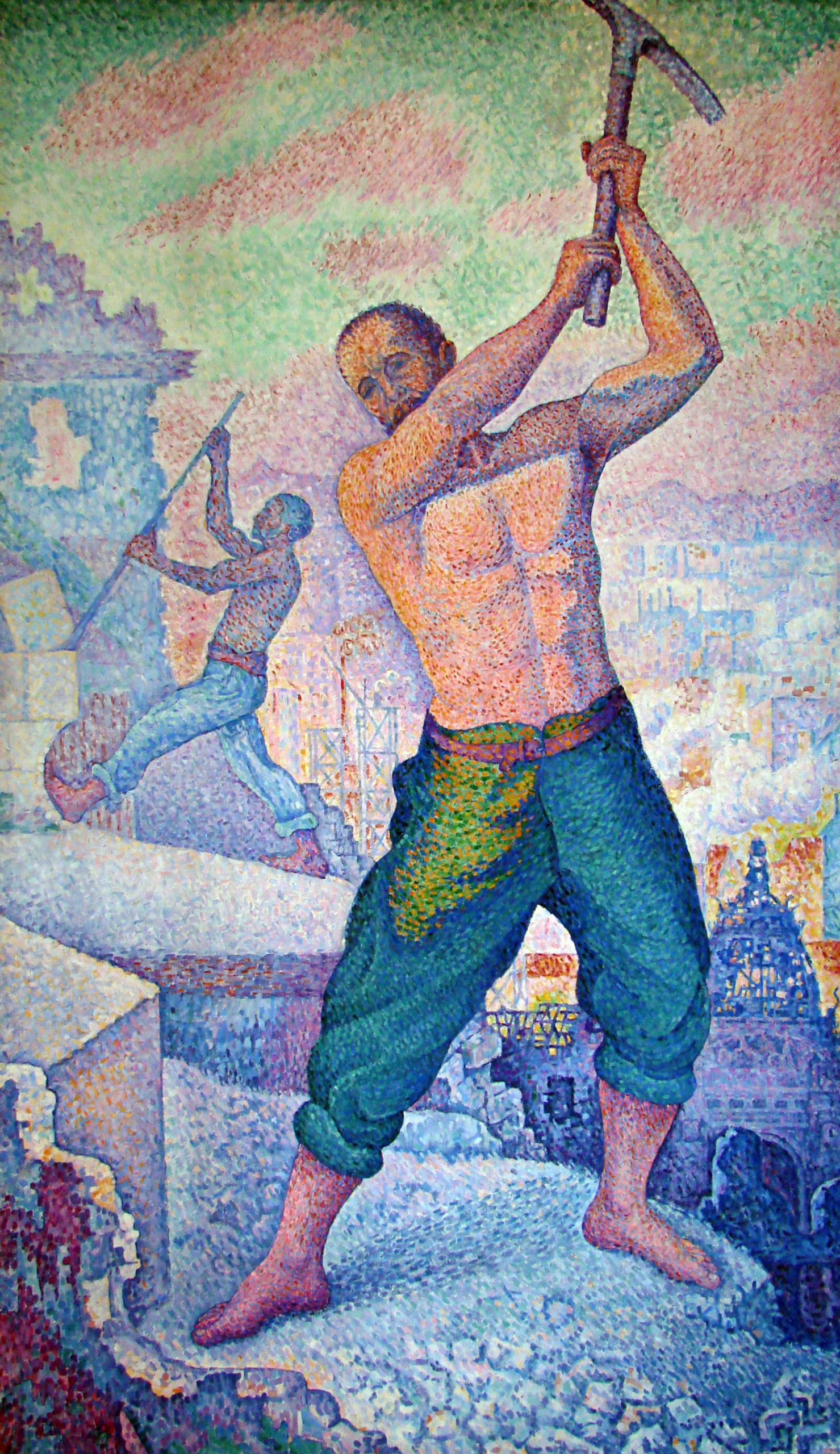

Perhaps it was this odd sense of unresolved class tensions that caused Signac to suggest that even Seurat’s paintings of “the pleasures of decadence” are about exposing “the degradation of our era” and bearing witness to “the great social struggle that is now taking place between workers and capital.” [2] Seurat’s own politics were unclear, but Signac was a social anarchist, as were several other Neo-Impressionists, including Camille Pissarro and his son Lucien, as well as Maximilian Luce, Theodore van Rysselberghe, Henri Cross, and the critic Felix Fénéon. Social anarchists reject a strong centralized government in which the state owns the means of production and guides the economy; they believe that social ownership and cooperation will emerge naturally in a stateless society.

Signac’s In the Time of Harmony was originally titled In the Time of Anarchy, but political controversy forced a change. Between 1892 and 1894 there were eleven bombings in France by anarchists, and a very public trial of suspected anarchists that included Fénéon and Luce.

Signac’s painting was intended to show that, despite its current revolutionary tactics, the aim of anarchism was a peaceful utopia. In the foreground, workers lay down their tools for a picnic of figs and champagne while others play at boules. A couple in the center contemplates a posy, while behind them a man sows and women hang laundry. Although the mood is timeless — with different clothing, this painting could be a Classical pastoral scene — in the distance modern mechanical farm equipment reinforces the painting’s subtitle, “The Golden Age is Not in the Past, it is in the Future.”

Relatively few Neo-Impressionist paintings are so overtly allegorical and political. Signac argued that it was the Neo-Impressionists’ technique, not any directly socialist or anarchist subject matter, that was most in tune with the political revolutionaries. The Neo-Impressionists’ rigorous appeal to hard science, rather than dead conventions, along with their uncompromising will to “paint what they see, as they feel it,” will help “give a hard blow of the pick-axe to the old social structure” and promote a corresponding social revolution. [3]

Notes:

- Henri Fèvre, “L’Exposition des Impressionnistes,” in Étude sur le Salon de 1886 et sur l’exposition des impressionnistes (Paris, 1886), p. 43 (our translation).

- Paul Signac, “Impressionists and Revolutionaries,” La Révolte, June 13-19, 1891, as translated in Nochlin, ed., p. 124.

- ibid., p. 124.

Neo-Impressionist Color Theory

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

In 1899, the artist Paul Signac rejected the “Pointillist” label and asserted, “The Neo-Impressionist does not dot, he divides.” He laid out a four-part argument outlining how division achieves the goals of “luminosity” and “harmony” by means of:

- The optical mixture of solely pure pigments (all the tints of the prism and all their tones);

- The separation of the different elements (local color, color of the lighting, their interactions, etc.);

- The equilibration of these elements and their proportions (according to the laws of contrast, of gradation, and of irradiation);

- The choice of a brushstroke commensurate with the dimensions of the painting. [1]

Signac’s argument is dense with the technical vocabulary of late-nineteenth century color theory. The Neo-Impressionists prided themselves on bringing scientific rigor to the hitherto largely intuitive Impressionist project. By understanding the contemporary meanings of Signac’s terms, we can trace how scientific color theory affected Neo-Impressionist practice.

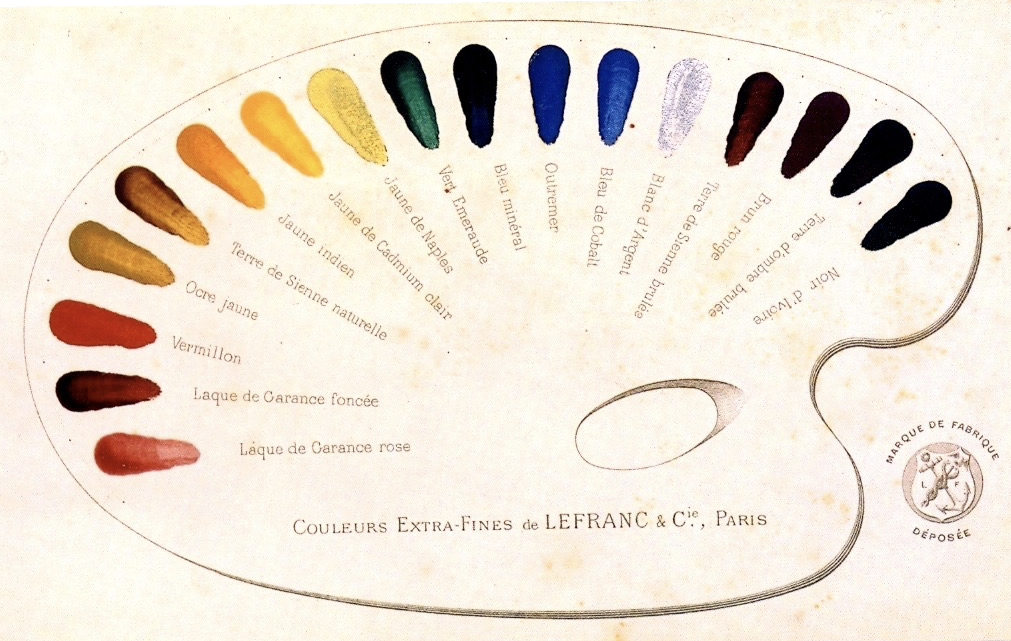

The Neo-Impressionist uses “solely pure pigments,” which Signac specifies as the colors of the “prism.” This wording already suggests a scientific basis for Neo-Impressionist color usage. In the seventeenth century the English physicist Sir Isaac Newton used a glass prism to separate white light into a rainbow. In painters’ terms, the colors of the prism correspond to the primary colors red, yellow, and blue, the secondary colors orange, green, and violet, and the tertiary colors blue-violet, blue-green, yellow-green, etc.

The Neo-Impressionists would mix these hues or “tints” only with white to produce different values or “tones” (all the gradations of blue from light to dark, for example). Above all, they avoided the muddy earth colors that dominated European painters’ palettes before the late-nineteenth century.

In their quest for pure, bright colors, the Neo-Impressionists were aided by new pigments created through chemical synthesis, as opposed to the ground-up minerals or organic matter of traditional pigments. Analysis has shown that Seurat’s palette of 1889-90 consisted of many colors that were not available before the 19th century, including chrome yellow (invented 1797), cobalt blue (1803-04), cadmium orange (1820s), french ultramarine (1826), and manganese violet (1860s).

Brushstroke and optical mixture

The nickname “Pointillism” was given to the movement because of the artists’ tendency to paint in small dots (points in French). Signac objected to the term because it suggests a stylistic gimmick, but executing paintings in small, discrete brushstrokes was crucial to another key concept of the movement that he mentions above: optical mixture.

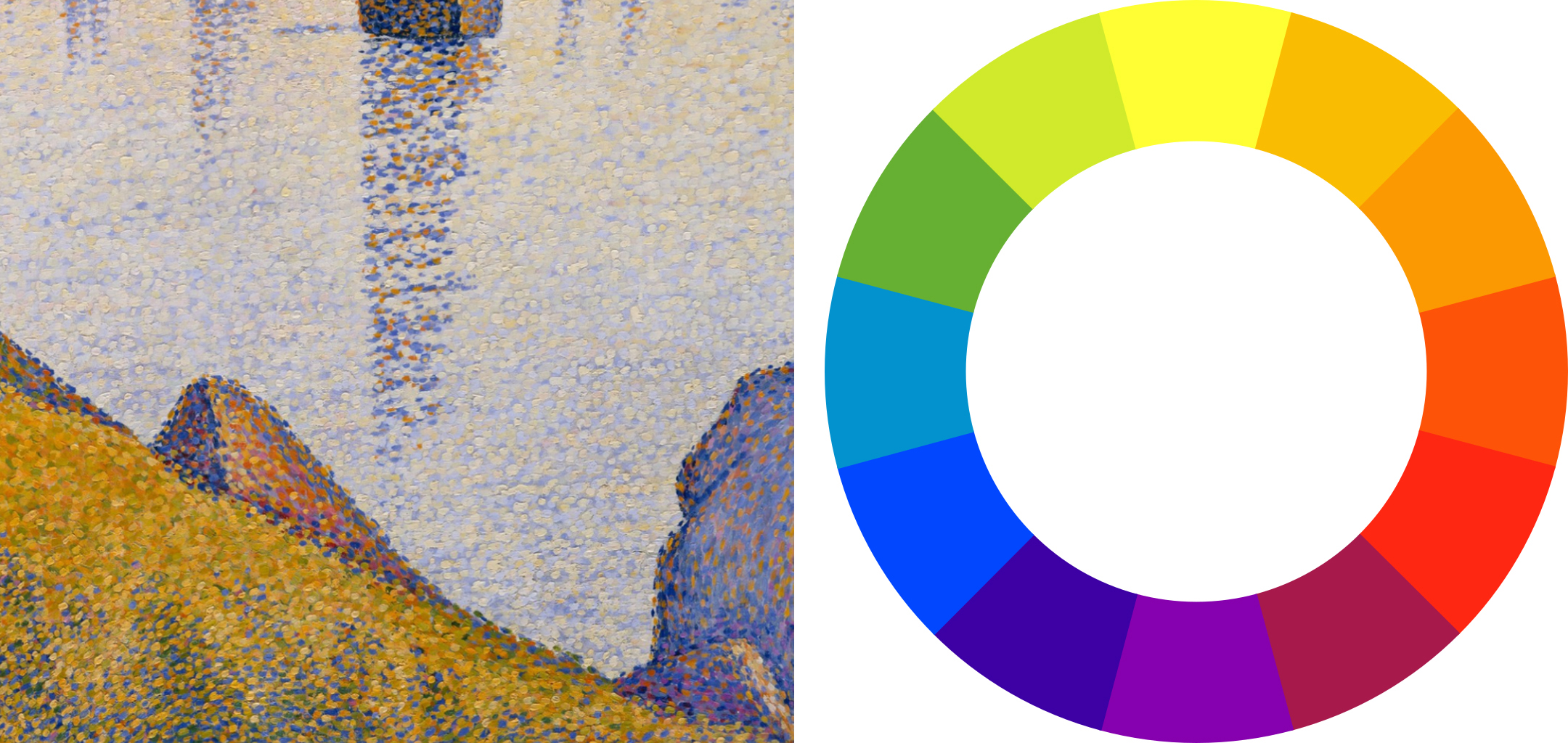

As any painter quickly realizes, whenever you blend two pigments, the resulting mixture is duller than either of the original pigments. This dulling effect is magnified the farther apart the colors are on the color wheel. Mixing blue and green results in a fairly bright blue-green, but mixing blue and orange creates dull grays and muddy browns.

Rather than mixing colors on the palette, the Neo-Impressionists would juxtapose them on the canvas in small dots. Seen from a suitable distance, these dots mix in the eye, and achieve the intended effects without losing the chromatic intensity of the original pigments.

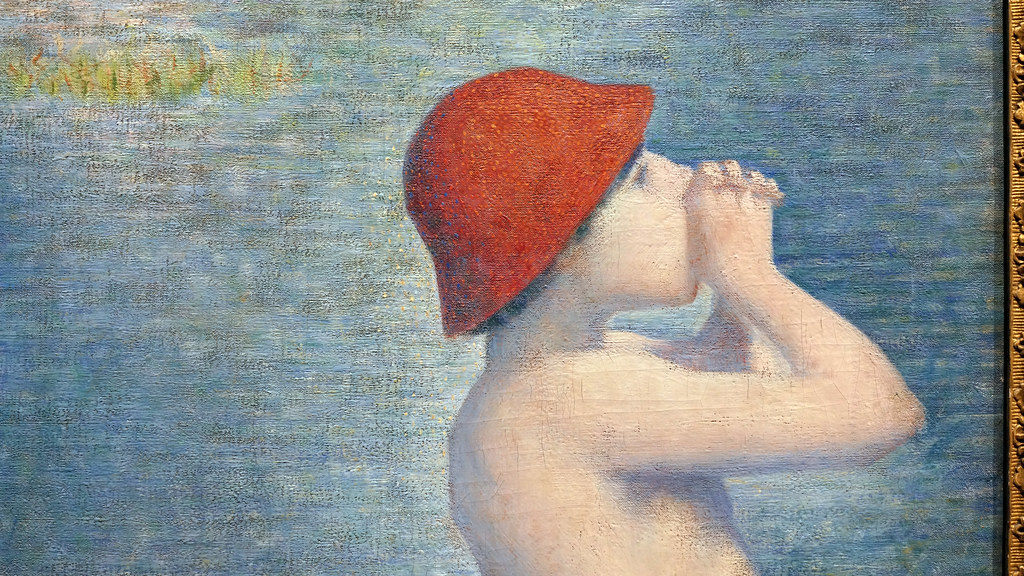

For example, the flesh of the women in Seurat’s The Models is made up of thousands of tiny dots of colors ranging from the expected light yellows, peaches, and pinks, to surprising blues, violets, and greens. Viewed from a sufficient distance, these colors blend in the eye to create a convincing and very luminous representation of the play of light and shadow across the models’ bodies.

The dots of color must be quite small in order for optical mixture to occur, although as Signac notes, their size could vary relative to the size of the painting. A mural meant to be read from a distance of several meters could use larger dots than a small landscape meant to be viewed up close.

Local color vs. perceived color

Signac’s preferred term “division” refers to the way the artist isolates all the component influences that contribute to a given perceived color. In the excerpt above, he lists the two main components: local color and the color of the light, along with “their interactions, etc.” Local color is what we think of as the actual color of the object itself: a yellow bus, a red apple, a white shirt. But simply painting an object in its local color ignores the effects of light on the object.

One of the effects of light is of course chiaroscuro: parts of the object struck by light are lighter than the parts in shadow. Camille Corot’s Bridge at Narni is a good example of a traditional landscape painted in local color and chiaroscuro. The bulk of the painting is in three basic colors: the green of the grass, the reddish tan of the dirt and bridge (and muddy water), and the blue of the sky and distant mountains. Corot has mixed darker and lighter values of each of these colors to show how the scene is affected by light coming from the sun in the upper right.

What Corot doesn’t emphasize, however, is what is called the color temperature of the light itself. A white shirt seen in a warm light will appear to be yellowish-orange, while viewed under cool light it will be tinted blue-violet.

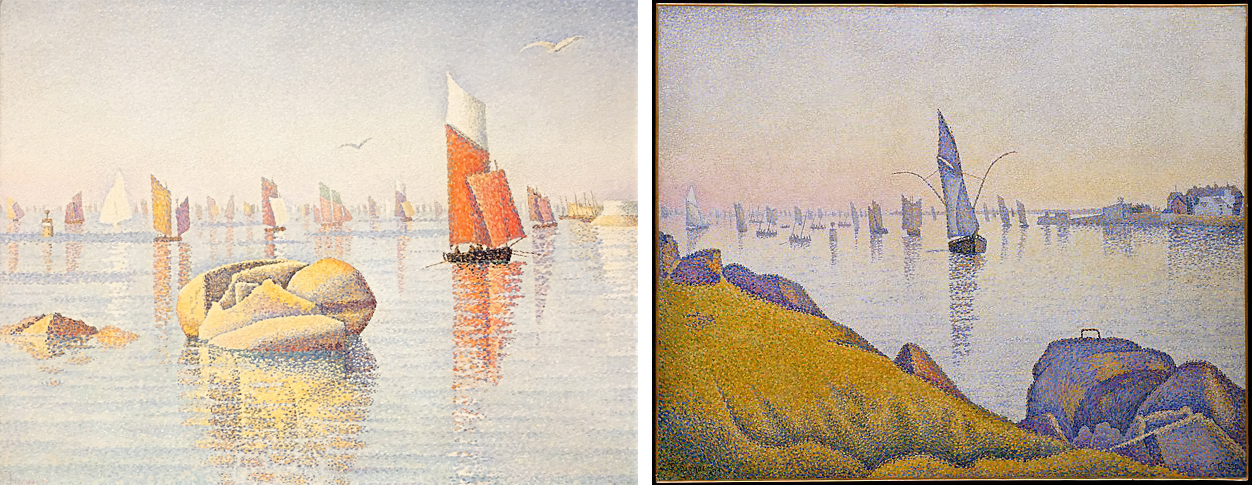

The color temperature of outdoor light is affected by the time of day, the season, and the weather. In these two paintings executed in the French coastal town of Concarneau, Signac pays close attention not just to the local colors of the objects, but also to their perceived colors — the colors that we actually see as they are affected by the temperature of the light. A palette based on orange and light blue depicts the bright, clear qualities of morning light, while a pinkish-yellow atmosphere with heavy, violet shadows conveys the effect of twilight.

Divisionism

The perceived color of any given object is the result of multiple factors, including the local color of the object, the color temperature of the light striking that object, possible reflected color from nearby objects, atmospheric perspective (which makes distant objects appear more blue-gray) and, as we shall see, the effect of “simultaneous contrast” with adjacent colors. Instead of blending all of these factors together, divisionism keeps them separate. The foreground grass in Signac’s Evening Calm includes dots of yellow and orange — the color of the light— to show how the greens are warmed by the light of the evening sun.

In the shadowed portions of the grass, Signac intersperses the greens with dots of cerulean and ultramarine blue. This is because shadow colors are the “complement” of the color of the light. Complementary colors are colors opposite one another on the color wheel, so the yellow-orange evening light produces violet-blue shadows.

This effect is even more strongly marked in the triangular rock jutting up from the center foreground, the lit side of which is shown glowing in the sunset through dots of orange, yellow, and rose. The shadowed side is dotted with mostly dark ultramarine blue, the complement of orange, although some interspersed oranges and even crimsons show the warm reflected light received from the grass. Rather than blending these complementary colors together, which would produce a dull muddy gray, Signac keeps them separate or divided, maintaining an overall intensity of color. Despite the improbable component colors, viewed from a proper distance, optical mixture produces a very convincing overall illusion of a rock bathed in warm evening light.

The law of contrast

Signac also mentions the artist’s need to take into account “the laws of contrast, of gradation, and of irradiation.” These “laws” refer to principles of color interaction discovered by nineteenth-century theorists such as Michel Chevreul, Ogden Rood, and Charles Henry, which seemed to promise that the entirety of art could be subsumed to rigorous scientific principles.

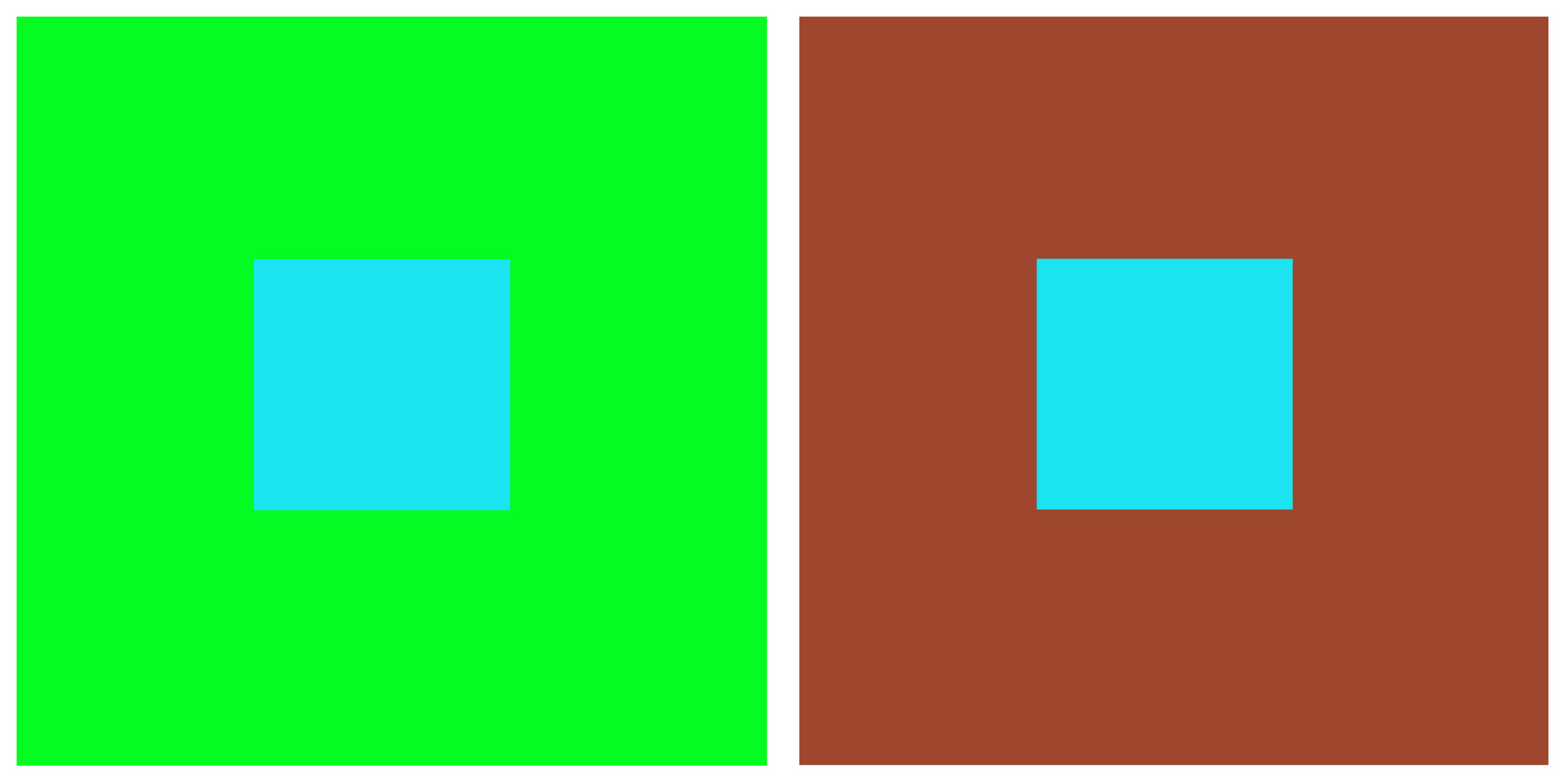

Chevreul’s most famous contribution to color theory is the “law of simultaneous contrast,” which takes account of how our perception of color changes relative to adjacent colors. Look at how different the same color swatch of blue appears against a field of bright green versus a field of dull orange, for example.

The general form of the law of simultaneous contrast is that two juxtaposed colors will appear maximally different from one another. Thus the blue appears both darker and duller when it is seen in a field of light, high-chroma yellow-green on the left, and it appears lighter and higher in chromatic intensity when seen against a field of dark, dull orange on the right.

Viewed against a white field, a swatch of color will actually gain a “halo” of its complementary color as a result of this effect. For example, if you gaze at the green swatch without focusing for several seconds, you will begin to see magenta edges emerge around it.

Seurat records this effect in his painting The Models. Notice how the seated model on the right has a dark, violet-blue halo around the light orange flesh of her back, and a light halo against the dark blue-violet shadowed side of her stomach and upper arm. This natural “irradiation” effect is exaggerated by Seurat in order to help intensify colors and values by juxtaposition with their opposites through simultaneous contrast.

Color perception, color harmony, color expression

We have concentrated here on how the Neo-Impressionists used color theory to help duplicate perceptual effects. They employed divisionism to keep their paintings as luminous as possible while recording how perceived color is affected by factors such as the temperature of the light, reflected color, and simultaneous contrast with adjacent colors.

The aims of the Neo-Impressionists went beyond perceptual accuracy to also include the purely aesthetic effects of color: how they can be used to create pleasing color harmonies based on certain principles. Signac’s “laws of contrast and gradation” evokes two of these principles: “gradation” is the aesthetic harmony produced by gentle transitions between largely analogous colors, and “contrast” is produced by the sharper juxtaposition of opposites. Later works by Signac seem more concerned with such harmonies than with perceptual accuracy.

The Neo-Impressionists also recognized that color has expressive effects. Signac claimed that “joy” is evoked by paintings with dominant warm and light tones, while “sorrow” is evoked by dominant cool and dark colors. [2] Ideally, a Neo-Impressionist painting will take into account all three qualities: perceptual accuracy, formal harmony, and emotional expression. The artists believed that all of these were susceptible to rigorous scientific laws that were just being recognized and systematized in their period.

Notes:

- Paul Signac, From Eugene Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, as translated in Linda Nochlin, ed., Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 1874-1904: Sources and Documents (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966), p. 118. This passage is very close to Georges Seurat’s own formulation of his method in a letter to Maurice Beaubourg of August 28, 1890: “The means of expression is the optical mixture of tones and colors (both of local color and of the illuminating color–sun, oil lamp, gas lamp, etc.), i.e., of the lights and their reactions (shadows) according to the laws of contrast, gradation, and irradiation” (in Nochlin, ed., p. 114).

- Ibid., p. 121.

Additional resources:

Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884, oil on canvas, 6.6 x 9.8 ft (National Gallery, London)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884, 1884-86, oil on canvas, 81-3/4 x 121-1/4 inches (207.5 x 308.1 cm) (The Art Institute of Chicago)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Vincent van Gogh

The Potato Eaters

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

What should a peasant painting smell like? Van Gogh has an opinion…

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Vincent van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, 1885, oil on canvas, 82 x 114 cm (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation). A conversation with Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker.

Additional resources:

Another version of this painting at the Kröller-Müller Museum

Van Gogh as a peasant painter — from the Van Gogh Museum

French Paintings of the 19th Century from The National Gallery of Art

Linda Nochlin and Dan Karlholm, “Misery, Beauty, and Other Issues: Linda Nochlin in Conversation with Dan Karlholm”

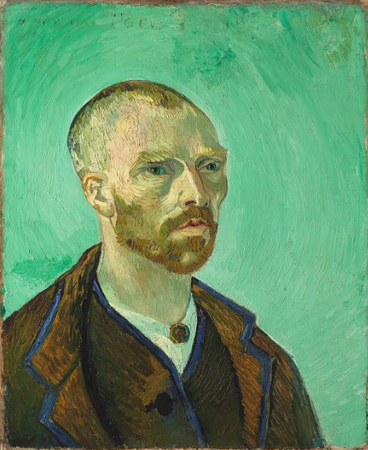

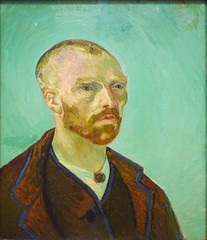

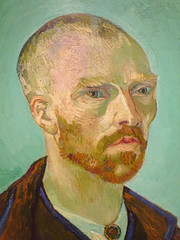

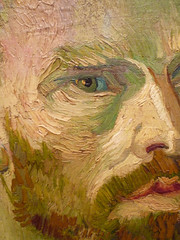

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin, 1888, oil on canvas, 24 x 19-11/16″ (Fogg, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts)

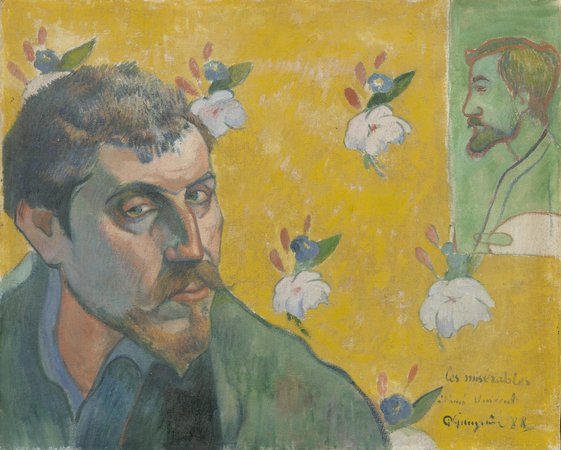

This self portrait was painted for Paul Gauguin as part of swap between the artists. Van Gogh chose to represent himself with monastic severity. The other painting is Paul Gauguin’s Self-Portrait Dedicated to Vincent van Gogh (Les Misérables). Gauguin’s title is a reference to the heroic fugitive, Jean Valjean, in Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables. Gauguin’s painting also contains a portrait of Emile Bernard that was painted not by Gauguin but by Bernard within Gauguin’s painting.

The following is a letter by Van Gogh to his brother Theo about the painting exchange with Gauguin dated October 7, 1888:

My dear Theo,

Many thanks for your letter. How glad I am for Gauguin; I shall not try to find words to tell you – let’s be of good heart.

I have just received the portrait of Gauguin by himself and the portrait of Bernard by Bernard and in the background of the portrait of Gauguin there is Bernard’s on the wall, and vice versa.

The Gauguin is of course remarkable, but I very much like Bernard’s picture. It is just the inner vision of a painter, a few abrupt tones, a few dark lines, but it has the distinction of a real, real Manet.

The Gauguin is more studied, carried further. That, along with what he says in his letter, gave me absolutely the impression of its representing a prisoner. Not a shadow of gaiety. Absolutely nothing of the flesh, but one can confidently put that down to his determination to make a melancholy effect, the flesh in the shadows has gone a dismal blue.

So now at last I have a chance to compare my painting with what the comrades are doing. My portrait, which I am sending to Gauguin in exchange, holds its own, I am sure of that. I have written to Gauguin in reply to his letter that if I might be allowed to stress my own personality in a portrait, I had done so in trying to convey in my portrait not only myself but an impressionist in general, had conceived it as the portrait of a bonze, a simple worshiper of the eternal Buddha.

And when I put Gauguin’s conception and my own side by side, mine is as grave, but less despairing. What Gauguin’s portrait says to me before all things is that he must not go on like this, he must become again the richer Gauguin of the “Negresses.”

I am very glad to have these two portraits, for they finally represent the comrades at this stage; they will not remain like that, they will come back to a more serene life.

And I see clearly that the duty laid upon me is to do everything I can to lessen our poverty.

No good comes the way in this painter’s job. I feel that he is more Millet than I, but I am more Diaz then he, and like Diaz I am going to try to please the public, so that a few pennies may come into our community. I have spent more than they, but I do not care a bit now that I see their painting—they have worked in too much poverty to succeed.

Mind you, I have better and more saleable stuff than what I have sent you, and I feel that I can go on doing it. I have confidence in it at last. I know that it will do some people’s hearts good to find poetic subjects again, “The Starry Sky,” “The Vines in Leaf,” “The Furrows,” the “Poet’s Garden.”

So then I believe that it is your duty and mine to demand comparative wealth just because we have very great artists to keep alive. But at the moment you are as fortunate, or at least fortunate in the same way, as Sensier if you have Gauguin and I hope he will be with us heart and soul. There is no hurry, but in any case I think that he will like the house so much as a studio that he will agree to being its head. Give us half a year and see what that will mean.

Bernard has again sent me a collection of ten drawings with a daring poem – the whole is called At the Brothel.

You will soon see these things, but I shall send you the portraits when I have had them to look at for some time.

I hope you will write soon, I am very hard up because of the stretchers and frames that I ordered.

What you told me of Freret gave me pleasure, but I venture to think that I shall do things which will please him better, and you too.

Yesterday I painted a sunset.

Gauguin looks ill and tormented in his portrait!! You wait, that will not last, and it will be very interesting to compare this portrait with the one he will do of himself in six months’ time.

Someday you will also see my self-portrait, which I am sending to Gauguin, because he will keep it, I hope.

It is all ashen gray against pale veronese (no yellow). The clothes are this brown coat with a blue border, but I have exaggerated the brown into purple, and the width of the blue borders.

The head is modeled in light colours painted in a thick impasto against the light background with hardly any shadows. Only I have made the eyes slightly slanting like the Japanese.

Write me soon and the best of luck. How happy old Gauguin will be.

A good handshake, and thank Freret for the pleasure he has given me. Good-by for now.

Ever yours,

Vincent.

Letter courtesy of Web Exhibits

Additional resources:

This painting at the Harvard Museums

Paul Gauiguin’s Self Portrait with Portrait of Émile Bernard at the Van Gogh Museum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

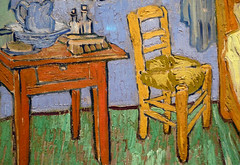

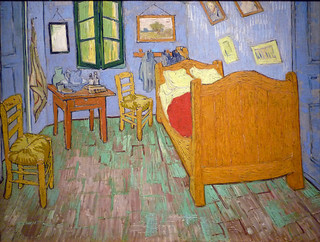

Vincent van Gogh, The Bedroom

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Vincent van Gogh, The Bedroom, 1889, oil on canvas, 29 x 36-5/8 inches ( 73.6 x 92.3 cm) (Art Institute of Chicago)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

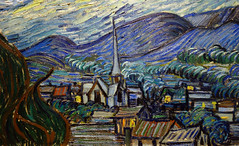

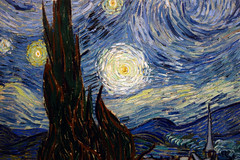

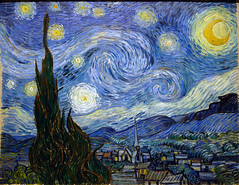

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night

by DR. NOELLE PAULSON

A rare night landscape

The curving, swirling lines of hills, mountains, and sky, the brilliantly contrasting blues and yellows, the large, flame-like cypress trees, and the thickly layered brushstrokes of Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night are ingrained in the minds of many as an expression of the artist’s turbulent state-of-mind. Van Gogh’s canvas is indeed an exceptional work of art, not only in terms of its quality but also within the artist’s oeuvre, since in comparison to favored subjects like irises, sunflowers, or wheat fields, night landscapes are rare. Nevertheless, it is surprising that The Starry Night has become so well known. Van Gogh mentioned it briefly in his letters as a simple “study of night” or ”night effect.”

His brother Theo, manager of a Parisian art gallery and a gifted connoisseur of contemporary art, was unimpressed, telling Vincent, “I clearly sense what preoccupies you in the new canvases like the village in the moonlight… but I feel that the search for style takes away the real sentiment of things” (813, 22 October 1889). Although Theo van Gogh felt that the painting ultimately pushed style too far at the expense of true emotive substance, the work has become iconic of individualized expression in modern landscape painting.

Technical challenges

Van Gogh had had the subject of a blue night sky dotted with yellow stars in mind for many months before he painted The Starry Night in late June or early July of 1889. It presented a few technical challenges he wished to confront—namely the use of contrasting color and the complications of painting en plein air (outdoors) at night—and he referenced it repeatedly in letters to family and friends as a promising if problematic theme. “A starry sky, for example, well – it’s a thing that I’d like to try to do,” Van Gogh confessed to the painter Emile Bernard in the spring of 1888, “but how to arrive at that unless I decide to work at home and from the imagination?” (596, 12 April 1888).

As an artist devoted to working whenever possible from prints and illustrations or outside in front of the landscape he was depicting, the idea of painting an invented scene from imagination troubled Van Gogh. When he did paint a first example of the full night sky in Starry Night over the Rhône (1888, oil on canvas, 72.5 x 92 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), an image of the French city of Arles at night, the work was completed outdoors with the help of gas lamplight, but evidence suggests that his second Starry Night was created largely if not exclusively in the studio.

Location

Following the dramatic end to his short-lived collaboration with the painter Paul Gauguin in Arles in 1888 and the infamous breakdown during which he mutilated part of his own ear, Van Gogh was ultimately hospitalized at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, an asylum and clinic for the mentally ill near the village of Saint-Rémy. During his convalescence there, Van Gogh was encouraged to paint, though he rarely ventured more than a few hundred yards from the asylum’s walls.

Besides his private room, from which he had a sweeping view of the mountain range of the Alpilles, he was also given a small studio for painting. Since this room did not look out upon the mountains but rather had a view of the asylum’s garden, it is assumed that Van Gogh composed The Starry Night using elements of a few previously completed works still stored in his studio, as well as aspects from imagination and memory. It has even been argued that the church’s spire in the village is somehow more Dutch in character and must have been painted as an amalgamation of several different church spires that van Gogh had depicted years earlier while living in the Netherlands.

Van Gogh also understood the painting to be an exercise in deliberate stylization, telling his brother, “These are exaggerations from the point of view of arrangement, their lines are contorted like those of ancient woodcuts” (805, c. 20 September 1889). Similar to his friends Bernard and Gauguin, van Gogh was experimenting with a style inspired in part by medieval woodcuts, with their thick outlines and simplified forms.

The colors of the night sky

On the other hand, The Starry Night evidences Van Gogh’s extended observation of the night sky. After leaving Paris for more rural areas in southern France, Van Gogh was able to spend hours contemplating the stars without interference from gas or electric city street lights, which were increasingly in use by the late nineteenth century. “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big” 777, c. 31 May – 6 June 1889). As he wrote to his sister Willemien van Gogh from Arles,

It often seems to me that the night is even more richly colored than the day, colored with the most intense violets, blues and greens. If you look carefully, you’ll see that some stars are lemony, others have a pink, green, forget-me-not blue glow. And without laboring the point, it’s clear to paint a starry sky it’s not nearly enough to put white spots on blue-black.

(678, 14 September 1888)

Van Gogh followed his own advice, and his canvas demonstrates the wide variety of colors he perceived on clear nights.

Invention, remembrance and observation

Arguably, it is this rich mixture of invention, remembrance, and observation combined with Van Gogh’s use of simplified forms, thick impasto, and boldly contrasting colors that has made the work so compelling to subsequent generations of viewers as well as to other artists. Inspiring and encouraging others is precisely what Van Gogh sought to achieve with his night scenes. When Starry Night over the Rhône was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants, an important and influential venue for vanguard artists in Paris, in 1889, Vincent told Theo he hoped that it “might give others the idea of doing night effects better than I do.” The Starry Night, his own subsequent “night effect,” became a foundational image for Expressionism as well as perhaps the most famous painting in Van Gogh’s oeuvre.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Paul Gauguin, Spirit of the Dead Watching

by BEN POLLITT

Be mysterious

“Soyez mysterieuses,” (be mysterious), Gauguin said. Perhaps he had this command in mind when he produced the most significant painting—by his own reckoning—to come out of his first stay in Tahiti, The Spirit of the Dead Watching. Few critics would doubt the importance of this work. Its mysteriousness and openness to interpretation has secured for it a position among Gauguin’s key works.

Gauguin made his first visit to Tahiti (a French colony) in March 1891, returning to Paris in May 1893. It was a hugely productive period in Gauguin’s career. “In the two years I have spent here,” he wrote, “with only a few months lost, I have produced sixty-six more or less fine canvases and a number of ultra-primitive sculptures. That is enough for any one man.”

A background of terror

To herald his return to Europe and also to rescue his family from penury, with the help of his Danish wife, Mette, Gauguin organized an exhibition of his work in Copenhagen. Among the nine canvases he sent from Tahiti was The Spirit of the Dead Watching, carrying with it an asking price—the most expensive in the sale—of between 1,500 and 2,000 francs. Clearly highly prized by Gauguin, the best of two years’ worth of “fine” canvases, the painting depicts an adolescent girl (the model was Gauguin’s Tahitian girlfriend Tehura, who was only fourteen years old), lying belly down on a bed, her face staring out at the viewer with a fearful expression. The bed is covered with a blue pareo (a wraparound skirt worn by Tahitians) and a light chrome-yellow sheet. Behind the bed, silhouetted and in profile, a woman watches over the child.

Gauguin created a haunting, supernatural quality by exploiting what he considered to be the emotional potential of color. When describing the painting to Mette, he points out how the shades of purple on the wall create “a background of terror” and how the sheet “must be yellow, because, in this color, it arouses something unexpected for the spectator.” Using colors to arouse feelings was very much in line with the work of other Post-Impressionist artists, such as Gauguin’s contemporary and friend, Vincent van Gogh.

The spirit of the dead

Aside from color, the composition is itself unsettling, particularly the relationship between the girl and the old woman behind her whose simplified form and disproportionate scale suggest Tahitian statuary or tiki. If she is a carved statue of wood, though, what or who does it signify? If not, then is she real or otherworldly? Is this the spirit of the dead watching that the title refers to? And if she is imagined, then by whom? Is all that surrounds the girl the conjurings of her own haunted imagination? Or is it what she looks out at—the space we ourselves inhabit—that is the source of her terror? Could it be, then, that we are the spirit of the dead watching? The Tahitian language certainly allows for such ambiguities. The expression, manao tupapau means either watching the spirit of the dead or the spirit of the dead watching.

Other formal features of the painting seem to enhance this ambivalence. Notice, for example, the complex vantage point we hold. Our gaze is level with the luminous eyes of the old woman, while at the same time, we look down at the figure of the young woman.

A slightly indecent study of a nude

We can also consider this painting within the tradition of the female nude and recall Manet’s Olympia (1865). Manet’s work provided a template for younger artists, one that rejected long-established conventions in the representation of the nude and challenged the moral values of the bourgeoisie. Gauguin, for one, admired Olympia enough to have produced a copy of it in 1891.

He was keen to shock the bourgeoisie and certainly his own nude in The Spirit of the Dead Watching—”a slightly indecent study” as he described it—is in many ways as radical as Manet’s. The body is awkwardly positioned and disproportionate. The feet overhang the bed and the hands are larger than the feet. And most shocking of all, is the age of the model.

Equally disturbing is the fear she exhibits. Gauguin described this in letters to his wife, Mette. Having walked that day to a neighboring village, Gauguin didn’t return to his house until the early morning. On entering, he found Tehura naked on the bed staring at him in terror. The reason for her fear, according to Gauguin, was that Tehura believed in tupapaus, the spirits of the dead who in Tahitian mythology inhabit the interior of the island and whose presence illuminates the forest at night.

Gauguin was skeptical about this belief, holding that these phosphorescent night glows that Tahitians took for spirits were in fact a type of fungus that grows on dead trees. Either way, for Tehura, to walk through the interior after sundown risked disturbing the tupapaus with potentially disastrous consequences; hence her fear and so too those glimmering spectral forms that feature in the background of the painting and that Gauguin stated stood for the tupapaus themselves.

Critical readings

Given his construction of Tahitian culture as “primitive,” Gauguin’s version of these events has been scrutinized by art historians who have cast doubt on whether Tehura would have actually held these beliefs (since she was a practicing Christian). Gauguin is thus accused of projecting his own primitivist preconceptions onto his subject.

Another critique comes from the art historian, Nancy Mowll Mathews, who argues that it was not the spirits that Tehura was frightened of, but Gauguin himself, the middle-aged, white, male colonialist against whom, as a sexual predator, she had little power to resist. This reading gives a disturbing twist to the image with Gauguin taking sadistic pleasure in depicting the fear that he himself caused. It’s worth noting that in Gauguin’s account, seeing her in this state moved him to declare that she never looked so beautiful, and that he was drawn to comfort her, promising never to leave her again.

The critic Stephen Eisenman takes a different line of argument, describing the painting as “an assault upon the tradition of the European nude.” Of particular interest for Eisenman is the viewer’s uncertainty regarding the sex of the figure, the large hands and narrow hips suggesting a male rather than a female form. “The posture and anatomy of Tehura, which emphasizes her boyishness, is derived from various androgynous and hermaphroditic prototypes,” Eisenman argues, citing the Borghese Hermaphrodite as one of them. Seen in this light, the painting, far from being an image of patriarchal dominion over the colonized body, is instead a subversive attack on that patriarchy and all the gendered values that it maintains.

However we choose to look at the painting, it provokes endless questioning, in which we are forced to encounter the other, whether that be in terms of age, faith, gender, spirituality, ethnicity, sexuality, culture, whatever you will, it is a painting that explores the heterogeneous nature of identity, asking profound questions as to who and what we are.

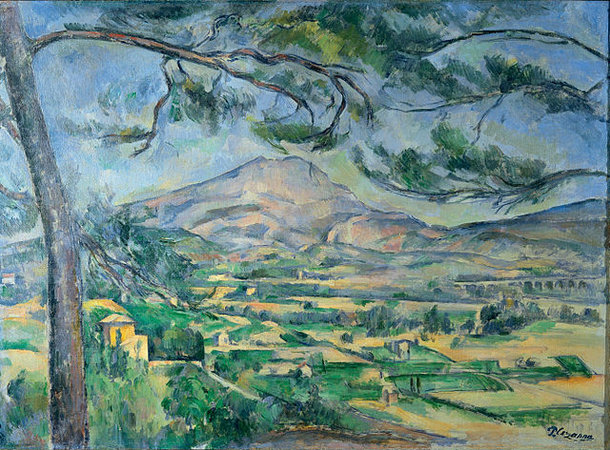

Paul Cézanne

An introduction to the painting of Paul Cézanne

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Categorizing the style of Paul Cézanne’s (Say-zahn) artwork is problematic. As a young man he left his home in Provence in the south of France in order to join with the avant-garde in Paris. He was successful, too. He fell in with the circle of young painters that surrounded Manet, he had been a childhood friend of the novelist, Emile Zola, who championed Manet, and he even showed at the first Impressionist exhibition, held at Nadar’s studio in 1874.

Out of place in Paris

However, Cézanne didn’t quite fit in with the group. Whereas many other painters in this circle were concerned primarily with the effects of light and reflected color, Cézanne remained deeply committed to form. Feeling out of place in Paris, he left after a relatively short period and returned to his home in Aix-en-Provence. He would remain in his native Provence for most of the rest of his life. He worked in the semi-isolation afforded by the country, but was never really out of touch with the breakthroughs of the avant-garde.

Working outdoors, but with a different purpose

Like the Impressionists, he often worked outdoors directly before his subjects. But unlike the Impressionists, Cézanne used color, not as an end in itself, but rather like line, as a tool with which to construct form and space. Ironically, it is the Parisian avant-garde that would eventually seek him out. In the first years of the 20th century, just at the end of Cézanne’s life, young artists would make a pilgrimage to Aix, to see the man who would change painting.

Influence

Paul Cézanne is often considered to be one of the most influential painter of the late 19th century. Pablo Picasso readily admitted his great debt to the elder master. Similarly, Henri Matisse once called Cézanne, “…the father of us all.” For many years The Museum of Modern Art in New York organized its permanent collection so as to begin with an entire room devoted to Cézanne’s painting. The Metropolitan Museum of Art also gives over an entire large room to him. Clearly, many artists and curators consider him enormously important.

Additional resources:

Cézanne’s Still Life with Apples at the MoMA

Biography of the artist from Grove Art on MoMA.org

Cézanne in Provence

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

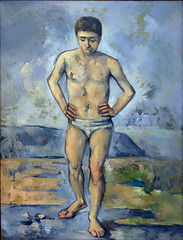

Paul Cézanne, The Bather

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

A figure in space

The picture is of a single male in an ambiguous landscape. The figure is pushed up to the front of the canvas and he fills it almost from top to bottom. Behind him, deep space is defined, but there is something of a visual tug-of-war going on. Cézanne has, as is traditional, defined both the near and distant ground planes. Unusually though, he leaves out the middle plane, which intensifies the distance between the fore and back-grounds. The trouble begins when he collapses the two.

Look closely at the contour that defines the edge of the figure. Don’t look inside the line that defines the edges of his body, look just outside (see especially beside the right leg). Cézanne has changed the brushwork and color just slightly. It appears that after the background and the figure were finished, he went back and reworked the part of the atmosphere surrounding the bather. The result is an odd shift in distance.

Rupturing illusion

The illusion of depth that allows our eye to travel back in space is ruptured as the reworked paint seems to cling to the foreground figure. It is as if the background is lifted forward, attaching itself to the edge of the man like a frame.

Why would Cézanne want to destroy the spacial relationships that he has carefully rendered? This sounds like something Edouard Manet might do. Like Manet, it is as if Cézanne wants the viewer to try to account for this distortion—and to engage actively in the picture and its construction.

Asymmetry

Such questions becomes even more insistent if we look at the rendering of the figure. Clearly this is not the work of Raphael nor of the refined academic technicians associated with the 19th-century Salon. It fact, the figure is a mess. Beyond being generalized, the parts do not seem to belong together. Look at the arms, for instance. The left doesn’t pair with the one on the right. The same is true of the chest and even the face. The legs are particularly awkward. Although one is forward, it is nevertheless far too long in relation to the other.

What is the careful observer to think? Has The Museum of Modern Art made a terrible mistake? Have museums around the world given over precious wall space to a charlatan? Cézanne could draw accurately when he chose, but in this instance he consciously chose to disregard tradition and represent space in a manner that invites the viewer to acknowledge both the illusion of depth and the dismantling of that illusion.

Additional resources:

Paul Cézanne from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Michael Kimmelman, “Cezanne, in All His Magnificent Mystery,” New York Times, 6/9/96

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Paul Cézanne, The Basket of Apples

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

In David’s Neo-Classical era, still life was considered the least important subject type. Only minor artists bothered with what was then seen as the most purely decorative and trivial of painting subjects. The hierarchy of subjects went roughly from the most important—historical and religious themes (often very large in scale); to important—portraiture (usually of moderate scale); less important—landscape & genre (themes of common life, usually of modest scale); to least important— still life (generally small canvases).

A hopeless subject

There had been one significant historical exception. In the 17th century in Northern Europe and particularly in the Netherlands, still life blossomed. But this period was brief and had little impact in France other than in the work of Chardin. So why would Cézanne turn so often to this discredited subject?

It was the very fact that still life was so neglected that seems to have attracted Cézanne to it. So outmoded was the iconography (symbolic forms and references) in still life that this rather hopeless subject was freed of virtually all convention. Here was a subject that offered extraordinary freedom, a blank slate that gave Cézanne the opportunity to invent meaning unfettered by tradition. And Cézanne would almost single-handedly revive the subject of still life making it an important subject for Picasso, Matisse, and others in the 20th century.

The image at the top of this page looks simple enough, a wine bottle, a basket tipped up to expose a bounty of fruit inside, a plate of what are perhaps stacked cookies or small rolls, and a tablecloth both gathered and draped. Nothing remarkable, at least not until one begins to notice the odd errors in drawing. Look, for instance, at the lines that represent the close and far edge of the table. I remember an old student of mine remarking to the class, “I would never hire him as a carpenter!” What she had noticed was the odd stepping of a line that we expect to be straight.

Purposeful errors

But that is not all that is wrong. The table seems to be too steeply tipped at the left, so much so that the fruit is in danger of rolling off it. The bottle looks tipsy and the cookies are very odd indeed. The cookies stacked below the top layer seem as if they are viewed from the side, but at the same moment, the two on top seem to pop upward as if we were looking down at them. This is an important key to understanding the questions that we’ve raised about Cézanne’s pictures so far.

Like Edouard Manet, from whom he borrowed so much, Cézanne was prompted to rethink the value of the various illusionistic techniques that he had inherited from the masters of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. This was due in part to the growing impact of photography and its transformation of modern representation. While Degas and Monet borrowed from the camera the fragmenting of time, Cézanne saw this mechanized segmentation of time as artificial and at odds with the perception of the human eye. By Cézanne’s era, the camera did shatter time into fragments as do non-digital cameras that can be set so that the shutter is open to light for only 1/1000 of a second.

Sight and memory

Cézanne pushed this distinction between the vision of the camera and of human vision. He reasoned that the same issues applied to the illusionism of the old masters, of Raphael, Leonardo, Caravaggio, etc. For instance, think about how linear perspective works. Since the Early Renaissance, constructing the illusion of space required that the artist remain frozen in a single point in space in order maintain consistent recession among all receding orthogonals. This frozen vantage point belongs to both the artist and then the viewer. But is it a full description of the the experience of human sight? Cézanne’s still life suggests that it is not.

If a Renaissance painter set out to render Cézanne’s still life objects (not that they would, mind you), that artist would have placed himself in a specific point before the table and taken great pains to render the collection of tabletop objects only from that original perspective. Every orthogonal line would remain consistent (and straight). But this is clearly not what Cézanne had in mind. His perspective seems jumbled. When we first look carefully, it may appear as if he was simply unable to draw, but if you spend more time, it may occur to you that Cézanne is, in fact, drawing carefully, although according to a new set of rules.

Seemingly simple, Cézanne’s concern with representing the true experience of sight had enormous implications for 20th century visual culture. Cézanne realized that unlike the fairly simple and static Renaissance vision of space, people actually see in a fashion that is more complex, we see through both time and space. In other words, we move as we see. In contemporary terms, one might say that human vision is less like the frozen vision of a still camera and more akin to the continuous vision of a video camera except that he worked with oil on canvas which dries and becomes static.

Purposeful destruction

So very tentatively, Cézanne began the purposeful destruction of the unified image. Look again at the cookies, or whatever they are, stacked upon the plate in the upper right. Is it possible that the gentle disagreements that we noted result from the representation of two slightly different view points? These are not large ruptures, but rather, they suggest careful and tentative discovery. It is as if Cézanne had simply depicted the bottom cookies as he looked across at them and then as he looked more slightly down at the top cookies after shifting his weight to his forward leg. Furthermore, I’m not sure that he was all that proud of these breaks that allow for more than a single perspective. Look, for instance, at the points where the table must break to express these multiple perspectives and you will notice that they are each hidden from view. Nevertheless, in doing this, Cézanne changed the direction of painting.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Art Institute of Chicago

Still Life tour from the National Gallery of Art

Selection on The Basket of Apples from Richard Brettell, Post-Impressionists. Chicago (1987, p. 67

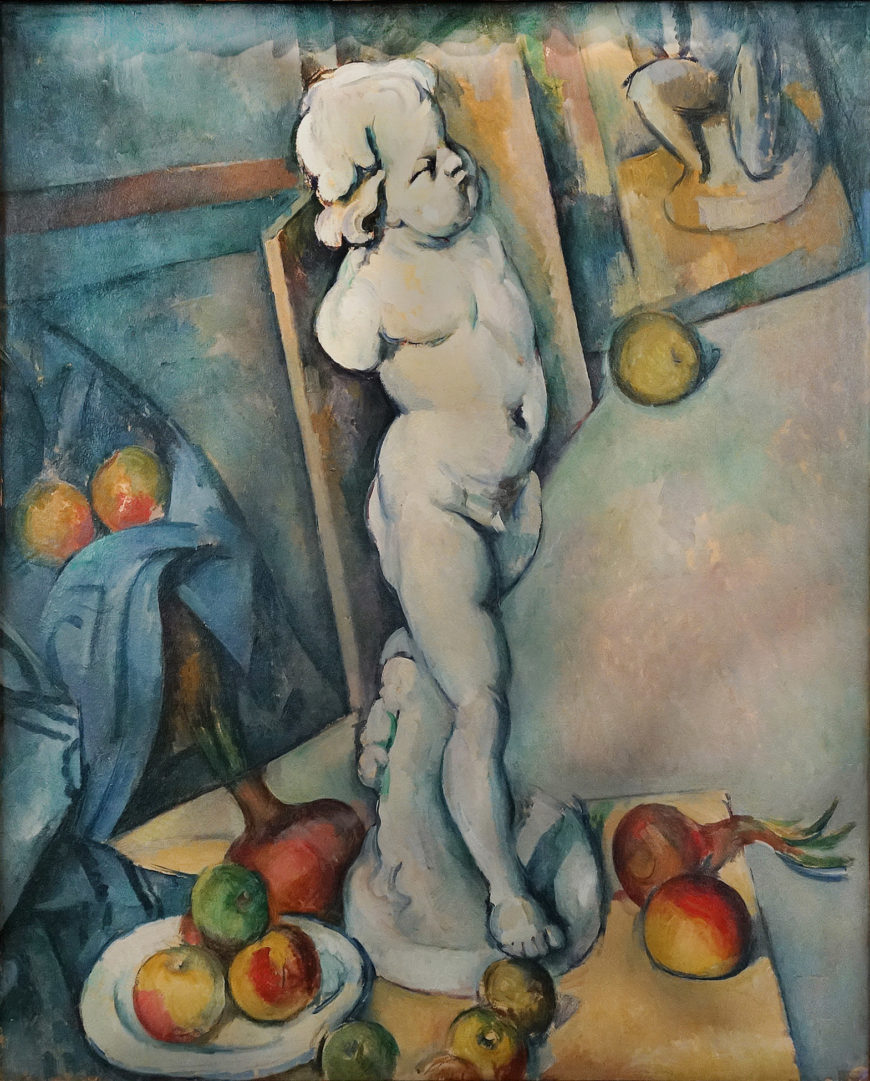

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Plaster Cupid

by RACHEL ROPEIK, DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Plaster Cupid, c.1895, oil on canvas (Courtauld Gallery, London)

René Descartes

I want to raise Cartesian philosophy here. The word is capitalized because it refers to the philosophy of the proto-Enlightenment thinker René Descartes. Even if you have never heard of this great rationalist, it is likely that you will recognize one of his phrases such as “I think, therefore, I am.” This odd sentence is the result of his effort to find irrefutable proof that he actually existed. Philosophers often ask questions that are meant to reveal fundamental truths. Can you imagine for a moment asking yourself this very question–How can I actually prove that I exist? Descartes realized an elegant solution, his very ability to ask the question was the proof of independent consciousness and therefore, of his existence.

With such questions, Descartes raised many considerations that would shape the modern world. Sometimes these questions raised, in turn, conclusions seemingly at odds with each other, such as his skepticism of both perception and of self-evident assumption

Objective and subjective knowledge

Ironically, such thoughts would eventually lead to a reappraisal of our confidence in society’s scientific empiricism. Empiricism relies upon objectivity. You will remember that the word “objective” means a truth that is beyond personal experience. In contrast, the word “subjective” is directly linked to personal experience.

Here is an example. Imagine a minor accident between a taxi and a city bus. A patrolman comes along to reconstruct the event. Does he only ask the cab driver what took place or does he also ask the passenger in the back of the cab and the bus driver and the riders on the bus? The cop’s goal is the reconstruct what “actually” happened. But if we take a post-Cartesian position we might ask whether there really was a single actual (objective) event or whether there were actually multiple (subjective) truths, each the result of each witness’s perspective. Let’s take a more directly applicable example. Look about the room that you are currently in. It probably has six sides: four walls, a floor, and a ceiling. When an architect drew a diagram of your room, he/she would have conceptually stepped outside of the space so that it could be understood in total.

But is this objective view a false one? Now in the built room, you cannot see its totality in a single moment. We can only see bits and pieces of the room at any one time and must rely upon memory to understand the room as a whole. Your more subjective experience has historically been considered less important than the architect’s objective conception even though you experience directly and the architect knows the room only theoretically.

Cézanne and subjective experience

Regarding the traditional hierarchical relationship between objective and subjective, Cézanne seems to ask, “which is more true?” and his conclusion mirrors an important development of modernism. In Still Life with Plaster Cupid, it is the subjective view that constructs the space. Cézanne has placed a plaster cast (copy) of an ancient Roman sculpture of a cupid (the son of Venus) on a tabletop so that it dominates the composition.

To an artist of the 19th century such classical sculpture would refer to the great humanist triumph of the Greeks and Romans and the birth of naturalism. In fact, one of the most prominent features of such sculpture would be its contrapposto (you remember this: axial shifts responding to weight borne by one leg). Actually, Cézanne’s li’l god-ling is also twisting at the waist, creating a subtle spiral torsion. Again, the space is odd, the floor especially, seems to rise up too steeply with the stacked canvases forming its uneven perimeter. Have you noticed that the canvases that line the floor, shape the space of the room and that this “shaping” is related to the twisting of the cupid? Let do this point by point. The right foot of the sculpture points roughly towards us and aligns, more or less, with the receding orthogonal of the table. The figure’s hips have turned. They are aligned with the plane of the canvas at the extreme left that is partly hidden behind the blue tablecloth. The Cupid’s shoulders are turned even further and align with the canvas that rests behind the godling’s torso.

This is clearly not the objective space of the architect. Cézanne has clearly sought to match the perception of space to the movement of the the body. But isn’t that what we really experience? When you walk into a room, do you see the room as an objective whole? No. We can only see a fragment at a time. But as we’ve already established, we don’t actually see in fragments; we see continuously and space is shaped by our continuous movement through it. Try it. Focus on any straight line in the room you are now in. Lean forward, and as you might expect, the angles of the room shift. In Still Life with Plaster Cupid, we see Cézanne’s attempt to render true human vision, vision that is subjective, continuous, and informed by memory.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Courtauld Gallery

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Why Is This Woman in the Jungle? Henri Rousseau’s The Dream

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\)

Artist Henri Rousseau painted The Dream in 1910, and it’s imagery of a woman lounging on a sofa in the middle of a jungle was as surreal then as it is today. What is it about this artwork that captivated audiences then and now?

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{16}\): Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge, 1893-95, oil on canvas, 48-1/2 x 55-1/2 inches (123 x 141 cm) (Art Institute of Chicago)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning: