2.4: Victorian art

- Page ID

- 107356

Victorian art 1837–1901

Artists responded to the wealth generated by empire and industry—and its moral consequences.

The Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 1837 until her death in January of 1901. The era's later half overlaps with the first part of the Belle Époque era of Continental Europe. It was known as a profound period of cultural, social and economic reform, in which the rise of industrial cities and demise or rural life shaped attitudes to work, culture, the family and more.

The Pre-Raphaelites and mid-Victorian art

The era of Darwin, Tennyson, Dickens, labor laws, the Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts movement.

c. 1848 - 1870

A beginner's guide

A beginner’s guide to the Pre-Raphaelites

At first they were three

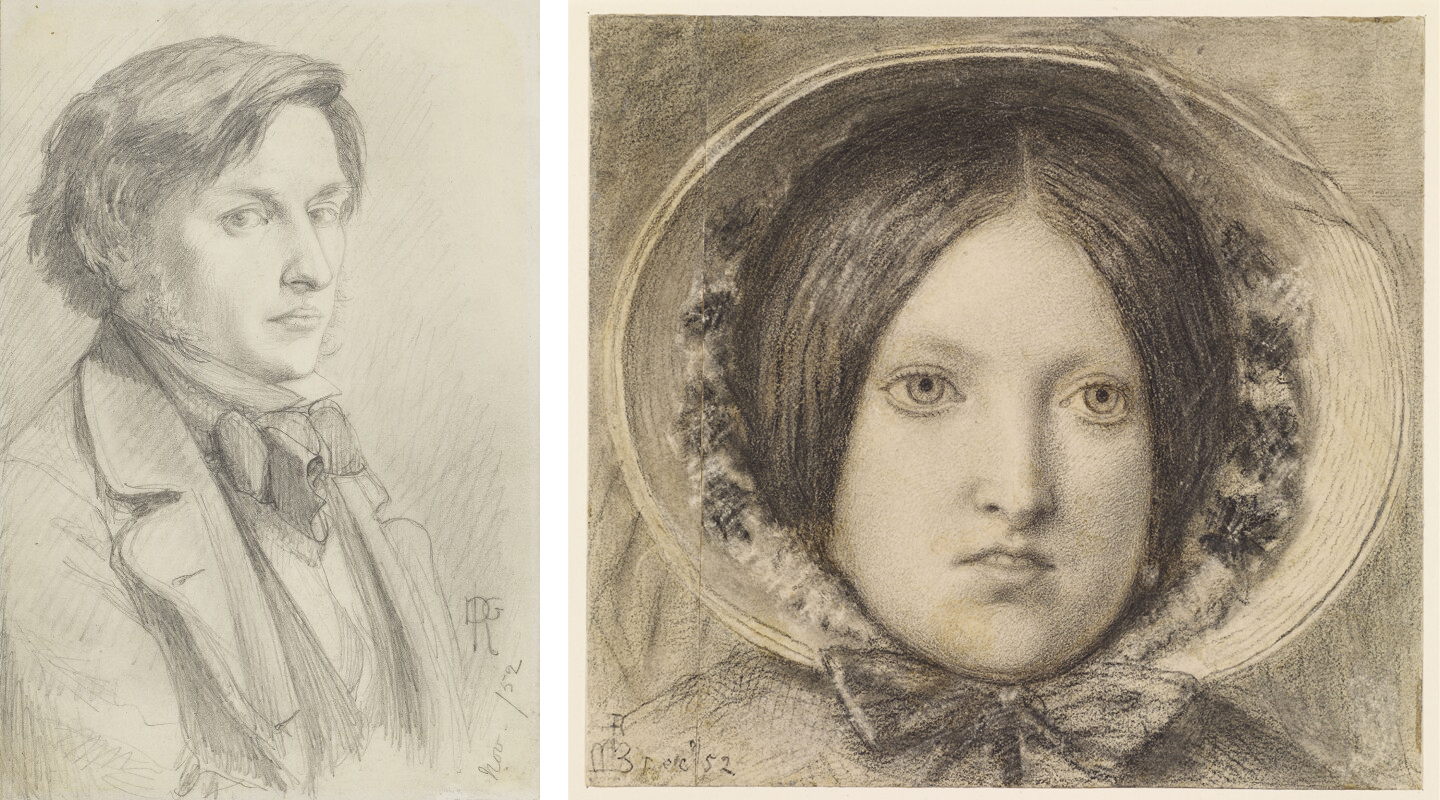

During a visit to the Royal Academy exhibition of 1848, the young artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti was drawn to a painting entitled The Eve of Saint Agnes by William Holman Hunt. As a subject taken from the poetry of John Keats was a rarity at the time, Rossetti sought out Hunt, and the two quickly became friends. Hunt then introduced Rossetti to his friend John Everett Millais, and the rest, as they say, is history. The trio went on to form the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group determined to reform the artistic establishment of Victorian England.

Looking back to look forward

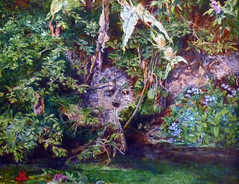

The name “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood” (PRB) hints at the vaguely medieval subject matter for which the group is known. The young artists appreciated the simplicity of line and large flat areas of brilliant color found in the early Italian painters before Raphael, as well as in 15th century Flemish art. These were not qualities favored by the more academic approach taught at the Royal Academy during the mid 19th century, which stressed the strong light and dark shading of the Old Masters. Another source of inspiration for the young artists was the writing of art critic John Ruskin, particularly the famous passage from Modern Painters telling artists “to go to nature in all singleness of heart . . . rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing.” This combination of influences contributed to the group’s extreme attention to detail, and the development of the wet white ground technique that produced the brilliant color for which they are known. The artists even became some of the first to complete sections of their canvases outdoors in an effort to capture the minute detail of every leaf and blade of grass.

And then they were seven

It was decided that seven was the appropriate number for a rebellious group and four others were added to form the initial Brotherhood. The selection of additional members has long mystified art historians. James Collinson, a painter, seems to have been added due to his short-lived engagement to Rossetti’s sister Christina rather than his sympathy with the cause. Another member, Thomas Woolner, was a sculptor rather than a painter. The final two members, William Michael Rossetti and Frederic George Stephens, both of whom went on to become art critics, were not practicing artists. However, other young artists such as Walter Howell Deverell and Charles Collins embraced the ideals of the PRB even though they were never formally elected as members.

The P.R.B. goes public

The Pre-Raphaelites decided to make their debut by sending a group of paintings, all bearing the initials “PRB”, to the Royal Academy in 1849. However, Rossetti, who was nervous about the reception of his painting The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, changed his mind and instead sent his painting to the earlier Free Exhibition (meaning there was no jury as there was at the Royal Academy). At the Royal Academy, Hunt exhibited Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes, a scene from an historical novel of the same name by Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Millais exhibited Isabella, another subject from Keats, created with such attention to detail that one can actually see the beheading scene on the plate nearest the edge of the table, which echoes the ultimate fate of the young lover Lorenzo in the story. In both paintings, the accurately designed medieval costumes, bright colors and attention to detail produced criticism that the paintings mimicked a “mediaeval illumination of the chronicle or the romance” (Athenaeum, 2 June 1849, p. 575). Interestingly, no mention was made of the mysterious “PRB” inscription.

Critical reaction

In 1850, however, the reaction to the PRB was very different. By this time, many people knew about the existence of the supposedly secret society, in part because the group had published many of their ideas in a short-lived literary magazine entitled The Germ. Rossetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini appeared at the Free Exhibition along with a painting by his friend Deverell entitled Twelfth Night. At the Royal Academy, Hunt’s A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Priest from the Persecution of the Druids and Millais’s Christ in the House of his Parents, famously abused by Charles Dickens, received the brunt of the criticism. In the aftermath of the humiliating reception of their work, Collinson resigned from the group and Rossetti decided never again to exhibit publicly.

Ruskin to the rescue

Undeterred, Millais and Hunt again continued to exhibit paintings demonstrating the beautiful colors and detail orientation of the mature style of the PRB. The Royal Academy of 1851 included Hunt’s Valentine Rescuing Sylvia, and three pictures by Millais, Mariana, The Woodman’s Daughter, and The Return of the Dove to the Ark as well as Convent Thoughts by Millais’s friend Charles Collins. Although many were still dubious about the new style, the critic John Ruskin came to the rescue of the group, publishing two letters in The Times newspaper in which he praised the relationship of the PRB to early Italian art. Although Ruskin was suspicious of what he termed the group’s “Catholic tendencies,” he liked the attention to detail and the color of the PRB paintings. Ruskin’s praise helped catapult the young artists to a new level.

The dissolution of the PRB

The Brotherhood, however, was slowly dissolving. Woolner emigrated to Australia in 1852. Hunt decided in January 1854 to visit the Holy Land in order to better paint religious pictures. And, in an event Rossetti described as the formal end of the PRB, Millais was elected as an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1853, joining the art establishment he had fought hard to change.

Lasting impact

Despite the fact that the Brotherhood lasted only a few short years, its impact was immense. Millais and Hunt both went on to establish important places for themselves in the Victorian art world. Millais was to go on to become an extremely popular artist, selling his art works for vast sums of money, and ultimately being elected as the President of the Royal Academy. Hunt, who perhaps stayed most true to the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, became a well-known artist and wrote many articles and books on the formation of the Brotherhood.

Rossetti became a mentor to a group of younger artists including Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Rossetti’s paintings of beautiful women also helped inaugurate the new Aesthetic Movement, or the taste for Art for Art’s Sake, in the later Victorian era.

To a contemporary audience, the Pre-Raphaelites may appear less than modern. However, in their own time the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood accomplished something revolutionary. They were one of the first groups to value painting out-of-doors for its “truth to nature,” and their concept of banding together to take on the art establishment helped to pave the way for later groups. The distinctive elements of their paintings, such as the extreme attention to detail, the brilliant colors and the beautiful rendition of literary subjects set them apart from other Victorian painters.

Additional resources:

The Pre-Raphaelites on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Series of videos on the Pre-Raphaelites from the Tate

William Holman Hunt’s The Eve of St. Agnes from the Google Art Project

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Aesthetic Movement

Art for the sake of art

The Aesthetic Movement, also known as “art for art’s sake,” permeated British culture during the latter part of the 19th century, as well as spreading to other countries such as the United States. Based on the idea that beauty was the most important element in life, writers, artists and designers sought to create works that were admired simply for their beauty rather than any narrative or moral function. This was, of course, a slap in the face to the tradition of art, which held that art needed to teach a lesson or provide a morally uplifting message. The movement blossomed into a cult devoted to the creation of beauty in all avenues of life from art and literature, to home decorating, to fashion, and embracing a new simplicity of style.

In literature

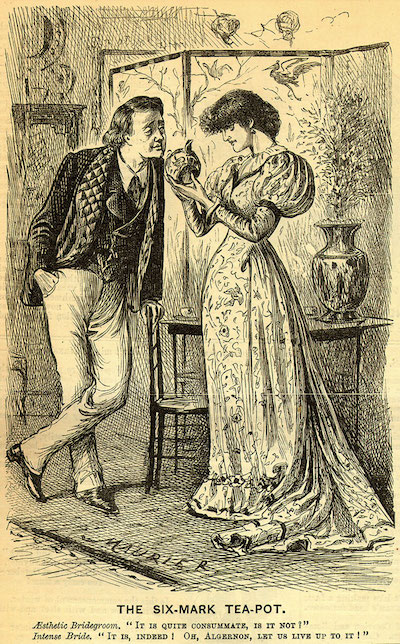

In literature, aestheticism was championed by Oscar Wilde and the poet Algernon Swinburne. Skepticism about their ideas can be seen in the vast amount of satirical material related to the two authors that appeared during the time. Gilbert and Sullivan, masters of the comic operetta, unfavorably critiqued aesthetic sensibilities in Patience (1881). The magazine Punch was filled with cartoons depicting languishing young men and swooning maidens wearing aesthetic clothing. One of the most famous of these, The Six-Mark Tea-Pot by George Du Maurier (left) published in 1880, was supposedly based on a comment made by Wilde. In it, a young couple dressed in the height of aesthetic fashion and standing in an interior filled with items popularized by the Aesthetes—an Asian screen, peacock feathers, and oriental blue and white porcelain—comically vow to “live up” to their latest acquisition.

In the visual arts

In the visual arts, the concept of art for art’s sake was widely influential. Many of the later paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, such as Monna Vanna (above), are simply portraits of beautiful women that are pleasing to the eye, rather than related to some literary story as in earlier Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

A similar approach can be seen in much of the work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, whose The Golden Stairs (1880) captures the aesthetic mood in its presentation of a long line of beautiful women walking down a staircase, devoid of any specific narrative content. The designer William Morris, another disciple of Rossetti, created beautiful designs for household textiles, wallpaper, and furniture to surround his clients with beauty.

“flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”

Most famous of the aesthetic artists was the American James Abbott McNeill Whistler. His early painting Symphony in White #1: The White Girl (left) caused a sensation when it was exhibited after being rejected from both the Salon in Paris (the official annual exhibition) and the annual exhibition at the Royal Academy in London. The simplistic representation of a woman in a white dress, standing in front of a white curtain was too unique for Victorian audiences, who tried desperately to connect the painting to some literary source—a connection Whistler himself always denied. The artist went on to create a series of paintings, the titles of which generally have some musical connection, which were simply intended to create a sense of mood and beauty. The most infamous of these, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875, Detroit Institute of Arts), appeared in an exhibition at London’s Grovesnor Gallery, a venue for avant garde art, in 1877 and provoked the famous accusation from the critic John Ruskin that the artist was “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

The ensuing libel trial between Whistler and Ruskin in 1878 was really a referendum on the question of whether or not art required more substance than just beauty. Finding in favor of Whistler, the jury upheld the basic principles of the Aesthetic Movement, but ultimately caused the artist’s bankruptcy by awarding him only one farthing in damages. In The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, a collection of essays published in 1890, Whistler himself pointed out the biggest problem for the aesthetic artist was that “the vast majority of English folk cannot and will not consider a picture as a picture, apart from any story which it may be supposed to tell.”

No story or moral message

The Aesthetic Movement provided a challenge to the Victorian public when it declared that art was divorced from any moral or narrative content. In an era when art was supposed to tell a story, the idea that a simple expression of mood or something merely beautiful to look at could be considered a work of art was a radical idea. However, in its assertion that a work of art can be divorced from narrative, the ideas of the Aesthetic Movement are an important stepping-stone in the road towards Modern Art.

John Everett Millais

Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents, 1849-50, oil on canvas, 864 x 1397 mm (Tate Britain, London)

A serious departure

When it appeared at the Royal Academy annual exhibition of 1850 Christ in the House of his Parents must have seemed a serious departure from standard religious imagery. Painted by the young John Everett Millais, a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (P.R.B.), Christ in the House of his Parents focuses on the ideal of truth to nature that was to become the hallmark of the Brotherhood.

The picture centers on the young Christ whose hand has been injured, being cared for by the Virgin, his mother. Christ’s wound, a perforation in his palm, foreshadows his ultimate end on the cross. A young St. John the Baptist carefully brings a bowl of water to clean the wound, symbolic of Christ washing the feet of his disciples. Joseph, St Anne (the Virgin’s mother) and a carpenter’s assistant also react to Christ’s accident. At a time when most religious paintings of the Holy Family were calm and tranquil groupings, this active event in the young life of the Savior must have seemed extremely radical.

The same can be said for Millais’ handling of the figures and the setting in the painting. Mary’s wrinkled brow and the less than clean feet of some of the figures are certainly not idealized. According to the principles of the P.R.B., the attention to detail is incredible. Each individual wood shaving on the floor is exquisitely painted, and the rough-hewn table is more functional than beautiful. The tools of the carpenters trade are evident hanging on the wall behind, while stacks of wood line the walls. The setting is a place of work, not a sacred spot.

Painted in a carpenter’s shop

William Michael Rossetti recorded in The P.R.B. Journal that Millais started to work on the subject in November 1849 and began the actual painting at the end of December. We know from Rossetti and the reminiscences of fellow Brotherhood member William Holman Hunt that Millais worked on location in a carpenter’s shop on Oxford Street, catching cold while working there in January. Millais’ son tells us that his father purchased sheep heads from a butcher to use as models for the sheep in the upper left of the canvas. He did not show the finished canvas to his friends until April of 1850.

Scathing reviews

Although Millais’ exhibit at the Royal Academy in 1849, Isabella, had been well received, the critics blasted Christ in the House of his Parents. The most infamous review, however, was the one by Charles Dickens that appeared in his magazine Household Words in June 1850. In it he described Christ as:

a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a nightgown, who appears to have received a poke playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a monster in the vilest cabaret in France or in the lowest gin-shop in England.

The commentary in The Times was equally unfavorable, stating that Millais’ “attempt to associate the Holy Family with the meanest details of a carpenter’s shop, with no conceivable omission of misery, of dirt, of even disease, all finished with loathsome minuteness, is disgusting.” The painting proved to be so controversial that Queen Victoria asked that it be removed from the exhibition and brought to her so she could examine it.

At the Royal Academy

The attacks on Millais’ painting were undoubtedly unsettling for the young artist. Millais had been born in 1829 on the island of Jersey, but his parents eventually moved to London to benefit their son’s artistic education. When Millais began at the Royal Academy school in 1840 he had the distinction of being the youngest person ever to have been admitted.

At the Royal Academy, Millais became friendly with the young William Holman Hunt, who in turn introduced Millais to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and the idea for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was born. The young artists exhibited their first set of paintings in 1849, all of which were well received, but the paintings shown in 1850 were universally criticized, although none with as much fervor as Christ in the House of his Parents.

Millais’ Christ in the House of his Parents is a remarkable religious painting for its time. It presents the Holy Family in a realistic manner, emphasizing the small details that bring the tableau to life. It is a scene we can easily imagine happening, but it is still laced with the symbolism expected of a Christian subject. It is Millais’ marriage of these two ideas that makes Christ in the House of his Parents such a compelling image, and at the same time, made it so reprehensible to Millais’ contemporaries.

Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1851-52, oil on canvas, 762 x 1118 mm (Tate Britain, London)

A Pre-Raphaelite masterpiece

Ophelia is considered to be one of the great masterpieces of the Pre-Raphaelite style. Combining his interest in Shakespearean subjects with intense attention to natural detail, Millais created a powerful and memorable image. His selection of the moment in the play Hamlet when Ophelia, driven mad by Hamlet’s murder of her father, drowns herself was very unusual for the time. However, it allowed Millais to show off both his technical skill and artistic vision.

The figure of Ophelia floats in the water, her mid section slowly beginning to sink. Clothed in an antique dress that the artist purchased specially for the painting, the viewer can clearly see the weight of the fabric as it floats, but also helps to pull her down. Her hands are in the pose of submission, accepting of her fate.

She is surrounded by a variety of summer flowers and other botanicals, some of which were explicitly described in Shakespeare’s text, while others are included for their symbolic meaning. For example, the ring of violets around Ophelia’s neck is a symbol of faithfulness, but can also refer to chastity and death.

The hazards of painting outdoors

Painted outdoors near Ewell in Surrey, Millais began the background of the painting in July of 1851. He reported that he got up everyday at 6 am, began work at 8, and did not return to his lodgings until 7 in the evening. He also recounted the problems of working outdoors in letters to his friend Mrs. Combe, later published in the biography of Millais by his son J.G. Millais.

“I sit tailor-fashion under an umbrella throwing a shadow scarcely larger than a halfpenny for eleven hours, with a child’s mug within reach to satisfy my thirst from the running stream beside me. I am threatened with a notice to appear before a magistrate for trespassing in a field and destroying the hay.”

The hazards of being an artist’s model

His problems did not end when he returned to his studio in mid-October to paint the figure of Ophelia. His model was Elizabeth Siddal who the Pre-Raphaelite artists met through their friend Walter Howell Deverell, who had been impressed by her appearance and asked her to model for him.

When she met the Pre-Raphaelites Siddal was working in a hat shop, but she later became a painter and poet in her own right. She also become the wife and muse of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Millais had Siddal floating in a bath of warm water kept hot with lamps under the tub. However, one day the lamps went out without being noticed by the engrossed Millais. Siddal caught cold, and her father threatened legal action for damages until Millais agreed to pay the doctor’s bills.

Millais becomes a success

Ophelia proved to be a more successful painting for Millais than some of his earlier works, such as Christ in the House of his Parents. It had already been purchased when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1852. Critical opinion, under the influence of John Ruskin, was also beginning to swing in the direction of the PRB (the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood). The following year, Millais was elected to be an Associate of the Royal Academy, an event that Rossetti considered to be the end of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

The execution of Ophelia shows the Pre-Raphaelite style at its best. Each reed swaying in the water, every leaf and flower are the product of direct and exacting observation of nature. As we watch the drowning woman slowly sink into the murky water, we experience the tinge of melancholy so common in Victorian art. It is in his ability to combine the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelites with Victorian sensibilities that Millais excels. His depiction of Ophelia is as unforgettable as the character herself.

Additional resources:

William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, 1853, oil on canvas, 762 x 559 mm (Tate Britain, London)

A Fallen Woman (with a New Twist)

William Holman Hunt’s painting, The Awakening Conscience, addresses the common Victorian narrative of the fallen woman (for more about this subject, see Stanhope’s Thoughts of the Past). Trapped in a newly decorated interior, Hunt’s heroine at first appears to be a stereotype of the age, a young unmarried woman engaged in an illicit liaison with her lover. This is made clear by the fact that she is partially undressed in the presence of a clothed man and wears no wedding ring.

However, Hunt offers a new twist on this story. The young woman springs up from her lover’s lap. She is reminded of her country roots by the music the man plays (the sheet music to Thomas Moore’s Oft in the Stilly Night sits on the piano), causing her to have an awakening prick of conscience.

The symbolism of the picture makes her situation as a kept woman clear—the enclosed interior, the cat playing with a bird under the chair, and the man’s one discarded glove on the floor all speak to the precarious position the woman has found herself in. However, as she stands up, a ray of light illuminates her from behind, almost like a halo, offering the viewer hope that she may yet find the strength to redeem herself.

The theme of the fallen woman was popular in Victorian art, echoing the prevalence of prostitution in Victorian society. Hunt’s redemptive message is unusual when compared to other examples of this theme. For example, Richard Redgrave’s The Outcast (1851), which shows a young unwed mother and her baby being cast out into the snow by her disgraced father, while the rest of her family pleads for mercy. Countless other paintings of the period emphasize the perils of stepping outside the bounds of acceptable morality with the typical conclusion to the story being that the woman is ostracized, and inevitably, suffers a premature death. By contrast, Hunt offers the viewer the hope that the young woman in his painting is truly repentant and can ultimately reclaim her life.

Pre-Raphaelite in style

The Awakening Conscience is one of the few Pre-Raphaelite paintings to deal with a subject from contemporary life, but it still retains the truth to nature and attention to detail common to the style. The texture of the carpet, the reflection in the mirror behind the girl and the carvings of the furniture all speak to to Hunt’s unwavering belief that the artist should recreate the scene as closely as possible, and paint from direct observation. To do that, he hired a room in the neighborhood of St. John’s Wood. The picture was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854, and unfortunately for Hunt, met with a mixed reception. While Ruskin praised the attention to detail, many critics disliked the subject of the painting and ignored the more positive spiritual message.

A deeply religious man

For Hunt, the moral of the story was an important element in any of his subjects. He was a deeply religious man and committed to the principles of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and John Ruskin. In fact, shortly after this painting was completed, Hunt embarked on a journey to the Holy Land, convinced that in order to paint religious subjects, he had to go to the actual source for inspiration. The fact that a trip to the Holy Land was a difficult, expensive and dangerous journey at the time was immaterial to him.

The Awakening Conscience is an unconventional approach to a common subject. Hunt’s work reflects the ideal of Christian charity espoused in theory by many Victorians, but not exactly put into practice when dealing with the issue of the fallen woman. While others emphasized the consequences of one’s actions as a way of discouraging inappropriate behavior, Hunt maintained that the truly repentant can change their lives.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Google Art Project

William Holman Hunt in the Google Art Project

The Pre-Raphaelites at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource at Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Ford Madox Brown

Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England

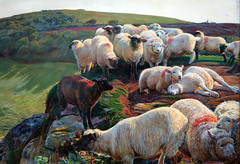

Ford Madox Brown’s great modern life study The Last of England (1852-55) captures a familiar scene in England during the 1850s. A man and woman aboard a crowded ship gaze out at the viewer. A brisk wind blows the woman’s bonnet ties and turns the sea into a mass of white caps, suggesting the potential for a rough passage. The deck behind them is packed with people also making the journey, while green cabbages hanging on the rope railings hint at the long voyage ahead. The predominately somber color scheme, the chilly look of the sea and the sky, and the mournful expressions of the main figures tell the story.

The painting is dominated by the two figures, based on the artist and his wife, Emma. Their close proximity and clasped hands identify them as a couple, yet they both stare straight ahead, each locked in their own silent reflections. Barely noticed at first glance is the small hand emerging out of the woman’s cloak, the unseen child that is potentially a nod to the future. The umbrella propped up to shield them from the spray of the sea also blocks their view of the iconic white cliffs of Dover receding in the distance, representing what is left behind. The unusual circular format of the painting acts almost like a telescope, adding a voyeuristic quality to the scene, as if the viewer is spying on this moment of personal grief and introspection. In a catalogue of his paintings written in 1865, Brown described The Last of England as “the parting scene in its fullest tragic development.” He also alludes to the superior class status of the couple compared to most of those in the background as “a couple from the middle class, high enough, through education and refinement, to appreciate all they are now giving up.”

Inspiration for the painting came from the departure of the sculptor Thomas Woolner, an original member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who joined the exodus to dig for gold in Australia in 1852. This came during a period of massive emigration from Britain—between circa 1815 and 1914 approximately ten million people sailed away, primarily to the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, hoping to improve their personal prospects. Unlike Woolner, who returned (without gold) to England in 1854, many of these people never saw their homeland again. Nor were they expected to return, which explains the couple’s mournful expressions. Other painters of the day addressed the subject of emigration, most notably Richard Redgrave in his The Emigrant’s Last Sight of Home (1858). However, Redgrave’s depiction of a family leaving a small village to begin their long journey is far more optimistic. In Redgrave’s work, the sunny sky, vivid green landscape, and the father’s theatrical wave of his hat as a final gesture of farewell create a feeling of hope largely missing from Brown’s painting.

Brown worked on this image over a period of years. Painted for the most part in his backyard, the artist worked on cold days using his family and local people as models. For example, when the painting was nearing completion, he recorded in his diary “it was the weather for my picture & made my hand look blue with the cold as I require in the work, so I painted all day out in the garden.” The minute detail of the purplish flesh on the exposed hands of the man in the foreground attests to Brown’s attention to detail. The glowering expression on the man’s face may also relate to Brown’s own emotions, as at the time he was struggling to achieve commercial success and himself entertained the idea of emigration.

The Last of England is a poignant reminder of the journey made by millions of people during the 19th century. At a time when many people are interested in genealogy and learning where they came from, it is a visual reminder of the hope and despair that these emigrants must have felt as they left their homes and families behind in search of a better life.

Additional resources:

Ford Madox Brown, Work

Victorian London

Construction projects have always been a part of city life, and Victorian London was no exception. Ford Madox Brown’s painting Work is a fascinating glimpse of just this. Our eye is immediately drawn to the young man in a striped hat effortlessly lifting a shovel high in the air, and the well-muscled forearms of the other workers.

Our eye then moves through the large canvas to the other figures, some more finely dressed and obviously of a different social class than the workers. But it is clear that Work is about more than just men digging. While the painting might appear to be a random view of a street, it is a carefully composed snapshot of the new way that different classes and professions encountered one another on the streets of Victorian London

Brown and the Pre-Raphaelites

Ford Madox Brown is associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of British artists noted for their attention to detail, vibrant colors, and interest in scenes from literature. Although Brown himself was never an official member of the PRB, he was friendly with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and others in the group. The two got to know each other when Rossetti appeared on Brown’s doorstep in 1848 asking for art lessons. Although the lessons were short-lived, the two developed a lasting friendship. Through his association with the PRB, Brown adopted many of their stylistic tendencies, particularly the use of bright colors and attention to detail.

Modern life

However, Brown’s paintings show a much greater interest in subjects of modern life than many of the other artists associated with the PRB. Brown recalled that he got the idea for Work from seeing navvies, or construction workers, excavating sewers in Hampstead, North London. The painting was begun in the summer of 1852. Brown traveled to the same spot in Hampstead every day, transporting his canvas back and forth by means of a special cart. The background landscape of the painting was completed right on the street in Hampstead so that Brown could capture the precise details of light, color and form. This interest in direct observation and specificity were hallmarks of the Pre-Raphaelite style.

Victorian ideas of class

The painting centers on a group of working-class navvies. These figures represent the noble “working man,” as they are neatly dressed and diligently going about their tasks. In contrast to the workers, there is a group of ragged children in the foreground, representing the lowest of the lower classes. In the catalog of his 1865 one-man exhibition, Brown tells us that the children’s mother is dead, and that the oldest, a girl of ten, is in charge of the rest of the children. She wears a tattered dress and is holding an infant over one shoulder.

Also representative of the lowest class is the ragged and barefoot plant seller on the left side, a figure whom Brown described as a “ragged wretch who has never been taught to work.” This hunched figure represents a stark contrast to the industrious and athletic navvies. shoveling away. Both the workers and the ragged children form another contrast, this time to the upper class figures depicted in the painting. On the left hand side, two ladies skirt the edge of the picture. The first, lady carrying a parasol, is a portrait of the artist’s Brown’s wife Emma. Following along behind is another well-dressed woman who offers a religious tract to one of the navvies. Seeing to the religious education of the lower classes was a type of “work” engaged in by many evangelical middle-class women.

In the background we see two riders on horseback, illustrating the landed upper classes, who by virtue of their wealth and place in society, have no need to work. These class distinctions are even carried over into the pets in the foreground of the painting. The mongrel dog with a frayed rope collar stands with the group of children and stares at his more pampered counterpart, a small dog with a red coat

Maurice and Carlyle

On the right side of the painting, two well-dressed men watch the navvies work. These figures are portraits of two prominent men of the day, Frederick Denison Maurice and Thomas Carlyle, whom Brown dubbed “brainworkers.” Carlyle, the figure with the hat and stick, was the author of Past and Present, a book advocating social reform that Brown had read with interest. Maurice was a leading Christian Socialist and founder of the Working Men’s College, where Brown was recruited as an instructor along with Rossetti and the art critic John Ruskin. One of the posters visible on the far left side on the canvas is an advertisement for the Working Men’s College.

At first glance Brown’s painting Work may appear to be an illustration of the stratification of social class in Victorian England. However, a deeper look reveals both a stunning example of the colorful and detailed Pre-Raphaelite style of painting as well as a commentary on the role of “work,” and its relationship to Victorian class structure. Work is at once a vivid reminder of both the class-consciousness of the Victorian age and the reforming spirit of that time which ultimately led to reforms like the ten-hour work day, and regulations restricting child labor.

Additional resources:

Interactive on this painting at Manchester City Art Gallery

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Proserpine

Fatal fruit

Just one bite. Surely that can’t hurt. Or can it? It took less than one bite to destroy the mythological goddess Proserpine’s life. This tragic maiden was gathering flowers when she was abducted by Pluto, carried off to his underground palace in Hades – the land of the dead, and forced to marry him. Distraught, her mother Ceres pleaded for her return. The god Jupiter agreed, on condition that Proserpine had not tasted any of the fruits of Hades. But she had—a single pomegranate seed—and as punishment she was destined to remain captive for six months of each year for the rest of her life in her bleak underground prison.

The English painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti produced at least eight paintings of Proserpine trapped in her subterranean world, the fatal pomegranate in her hand. He also wrote a sonnet to accompany the painting, which is inscribed in Italian on the painting itself and in English on the frame, cited below. This is the seventh version of the painting. It was produced for the wealthy ship-owner and art collector Frederick Leyland from Liverpool and is now in the Tate collection, London. The original idea was to paint Eve holding the forbidden apple, a scene from Genesis; and in fact the two stories are almost directly comparable. Eve and Proserpine both represent females banished for their sin of tasting a forbidden fruit. Their yielding to temptation has often been seen as a sign of feminine weakness or lack of restraint.

Twists and turns

At first glance the painting appears still, subdued—muted like the colour scheme. Proserpine is motionless, absorbed in thought, and the only sign of movement is the wisp of smoke furling from the incense burner, the attribute of the goddess. But look closely, and the painting appears to bristle with a tortuous, pent-up energy. It is full of peculiar twists and turns. Take Proserpine’s neck: it bulges unnaturally at the back, and looks as though it is slowly being screwed or twisted like rubber. Her hands too are set in an awkward grip. Try mimicking this yourself—it is difficult to hold this pose for long. This is a painting of almost tortured stillness: a body under strain.

This underlying unease is also apparent in the lines and creases of Proserpine’s dress. Notice how it does not form natural-looking folds. Instead it looks like the fabric is covered in clinging, creeping ridges that seem to slowly wind their way around the goddess, ensnaring and rooting her to the spot. These ridges could be compared to the tendril of ivy in the background, which appears to sprout directly from her head. Ivy is a plant with dark connotations—an invasive vine, it has a tendency to grip, cover and choke other plant-life. It is often associated with death, and is a common feature in graveyards. Rossetti wrote that the ivy in this painting symbolises ‘clinging memory.’ But what are these memories that cling so tightly?

Personal torment and morbid melancholy

As many have pointed out, this painting of Proserpine strikes a chord with Rossetti’s personal life. The writer Theodore Watts-Dunton, Rossetti’s close friend, wrote that “the public… Has determined to find in all Rossetti’s work the traces of a morbid melancholy… Because Proserpine’s expression is sad, it is assumed that the artist must have been suffering from a painful degree of mental depression while producing it.” Rossetti had, in fact, suffered a nervous breakdown just two years before he produced this painting. He suffered from acute paranoia, and was becoming increasingly reliant on alcohol and chloral for relief. There are doubtless many reasons for this, one of which was the death—or perhaps suicide—of his wife Lizzie Siddal in 1862, of a laudanum overdose. Rossetti and Lizzie’s relationship had been fraught and unstable. He was haunted by memories of her for the rest of his life.

But the plot thickens. When he painted Proserpine, Rossetti was entangled in a complicated love triangle. He was completely infatuated with the model for this painting, Jane Morris, easily recognizable by her thick raven hair, striking features and slender, elongated figure—though here they have been molded into the typical Rossettian type. Rossetti called her a “stunner.” The problem was that this stunner happened to be the wife of his good friend William Morris. When this was painted, the three were living together at Kelmscott Manor (Oxfordshire). Morris appeared either to tolerate or ignore the intimacy that cleaved Rossetti and his beloved Jane together. Many have noted the similarity between Proserpine and Jane’s personal predicaments: both were young women trapped in unhappy marriages, longing for freedom. But perhaps it is also a meditation on Rossetti’s own situation. Unable to contain his feelings for Jane, he had given in to temptation and for this was destined to live part of his life in secrecy and withdrawal. Rossetti himself had tasted the fatal fruit and was living with the consequences.

The problematic pleasures of taste

In this painting, a clear correspondence is set up between Proserpine’s improbably large lips and the pomegranate in her hand. While the rest of the painting has been completed in cool, sometimes murky colors—Rossetti called it a “study of greys” —the lips and pomegranate are vivid and intense, painted in warm orange and red tones. It is significant that these features—the mouth and the fruit—have strong associations with the pleasures of taste. It is as though Rossetti is presenting both as objects ripe for consumption, tempting the viewer to take a taste. This is not as improbable as it first sounds: one of Rossetti’s earlier paintings, Bocca Baciata (left), which also shows a single female figure with a fruit (an apple in this case) was considered capable of stirring an erotic, physical response in viewers. The artist Arthur Hughes, a contemporary of Rossetti’s, said that the owner of this painting would probably try to ‘kiss the dear thing’s lips away.’ In fact, the title of the painting itself translates as “the mouth that has been kissed.”

This sensual, carnal side of Rossetti’s work caused controversy during his lifetime—for a Victorian artist, he was venturing into dangerous territory. Even today some find his sexualized vision of feminine beauty difficult to stomach. Rossetti argued however that work was not just a study of the sensual in life. He insisted that his art was an attempt to synthesize the sensual and the spiritual. His fried Theodore Watts-Dunton defended this in an article “The Truth about Rossetti.” To Rossetti he wrote, “the human body, like everything in nature, was rich in symbol… To him the mouth really represented the sensuous part of the face no less certainly than the eyes represented the spiritualized part.” adding that if the lips of Rossetti’s women appear overly full and sensual, this is always counter-balanced by the spiritual depth invested in their eyes. It is true that in this painting there does appear to be a haunting melancholy in Proserpine’s eyes, but whether Rossetti fully achieves this synthesis of the sensual with the spiritual is still up for debate.

Afar away the light that brings cold cheer

Unto this wall, – one instant and no more

Admitted at my distant palace-door.

Afar the flowers of Enna from this drear

Dire fruit, which, tasted once, must thrall me here.

Afar those skies from this Tartarean grey

That chills me: and afar, how far away,

The nights that shall be from the days that were.

Afar from mine own self I seem, and wing

Strange ways in thought, and listen for a sign:

And still some heart unto some soul doth pine,

(Whose sounds mine inner sense is fain to bring,

Continually together murmuring,) –

“Woe’s me for thee, unhappy Proserpine!”—Dante Gabriel Rossetti, “Proserpina (For a Picture)”(1880)

Additional resources:

Another painting on this subject at the Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

This painting and subject on the Victorian Web

Proserpine on the Rossetti Archive

Bocca Baciata at Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Emily Mary Osborn, Nameless and Friendless

by BEN POLLITT

A studio of one’s own

Emily Mary Osborn was among the most successful Victorian women artists. Far from the well-trodden academic route followed by her male contemporaries, Osborn pursued her training with resourcefulness and tenacity, taking evening classes and persuading one of the teachers to give her private lessons, and then going on to study and work in his gallery.

Though success did follow, with regular exhibitions of her work at the Royal Academy and sales enabling her to set up a studio of her own, as a woman in the male-dominated world of the art market, Osborn must have been only too aware of the obstacles facing women artists. As a woman she was never granted membership of the Academy and could not study in the Royal Academy schools (women were admitted in small numbers after 1860). More generally, though, Osborn, like many of her contemporaries was deeply concerned with the issue of educational and employment opportunities for women. It is a recurrent theme in her work and is perhaps nowhere better illustrated than in her most famous painting, Nameless and Friendless.

The primal eye

A woman stands in a print-seller’s shop, beside her a boy, her brother, stands carrying a portfolio under his arm. The black dress and hood she wears tell of a recent loss. She is not wearing a mourning ring though, so she and her brother are probably orphans. Behind the counter to the right is the print- seller, a portly gentlemen, inspecting a small painting, a still life perhaps—the genre that, through lack of access to the life model, tended to be favored by women artists.

The anxious pose of the woman, her downcast eyes, her left shoulder coiled inwards as though guarding herself against the dealer’s critical gaze and the way, too, her hands toy nervously with a length of string, may lead us to assume that the painting is her own work. Her defensiveness is justified. The chair to the right is empty, the dealer having made no attempt at courtesy by offering her a seat. In the doorway another woman and boy make their way out, some rolled up sheets under the arm of the latter, while outside in the rain a woman is just visible walking along the pavement sheltering herself with an umbrella.

What the future holds

Like a continuous narrative (where we see more than one moment of time within a single canvas), do these peripheral figures hint at what awaits the woman and her brother, who, failing to sell her work, will soon be back walking the street? The orthogonal lines in the painting would seem to support this view, pointing conspicuously to the door as they do. So too, of course, does the title of the work, Nameless and Friendless, suggesting that without the necessary connections, a woman artist stands little chance of finding professional success.

A possible literary source for the painting is Mary Brunton’s novel Self-Control, first printed in 1810 and re-published in the 1850s, which tells the story of Laura Montreville who tries unsuccessfully to sell her paintings in order to help save her father from financial ruin. In one chapter of the novel Laura visits a number of print-sellers in the hope of selling her work, but each time is disappointed. On her fourth attempt, a young man, a former artist himself, admires her painting and agrees to hold it in his shop on a sale or return basis. Perhaps, if the book was indeed the source of the painting, Osborn had this fellow in mind when painting the man on the step ladder. The way his face echoes the woman’s hints at a certain sympathy between the two, while his elevated level suggests that his vision extends beyond the myopia of his colleagues, one of whom sits wearing glasses scratching away with a pen at a ledger.

Everywhere we look in fact men are engaged in looking. Outside the shopfront a man peers at one of the prints displayed in the window. The boy too levels his eyes at the print-seller in a challenging attitude, the red of his scarf suggestive of his fervor to champion his sister’s talents. This interplay of gazes is made still more complex with the two men seated to the left, customers who seem very much at home inspecting the prints. The seated figure holds a print of a dancing-girl, a ballerina, with her arms lifted above her head and her bare legs exposed. It is not the print however that they are looking at, but this young woman, vulnerable and distressed; the conspiratorial intimacy and the intentness of their gazes renders almost tangible the transference of their fantasies of the dancing girl onto this perhaps soon-to-be-fallen woman, whose part in all this seems almost unbearably passive. Her eyes cast down, as though, as Linda Nochlin puts it, the artist had now become the model to be looked at and judged.*

The rich man’s wealth is his strong city…

The title carries a quotation from the Biblical Book of Proverbs: “The rich man’s wealth is his strong city: the destruction of the poor is their poverty” (10:15). The passage goes on to develop the theme of the spiritual poverty of the rich, who complaisantly forget about God, a sentiment with which the Victorians would have been very familiar.

The “strong city” of London was witnessing an extraordinary expansion as a result of the Industrial Revolution. For some this was an enormously prosperous time, for the working class and for those on the margins of society, however, living conditions had never been worse and without any form of welfare a change in fortune could easily see you ending up not just nameless and friendless, but homeless and penniless. Without adequate opportunities for gainful employment, single, middle-class women were among the most vulnerable.

By quoting scripture, Osborn perhaps is encouraging us to read the painting more universally than as the depiction of a struggling woman artist: the point being that the great divides operating in Victorian society between the haves and the have-nots (what the Victorians called the “two nations”), as well as men and women, make us all the poorer. The quotation might also tempt us to a religious reading of the painting. The woman herself, though clearly outnumbered and surrounded by men on all sides, still dominates the composition—the implication being that though meek and mild, spiritually she is the strongest.

An image of its time

For some, the problem with Osborn’s painting is that the woman is presented as too passive, too willingly accepting of rejection, too much of a martyr to male prejudices and male desires. Rather than breaking down the gender divide, then, the painting instead seems to perpetuate it. As valid as this argument is, as an early or proto-feminist painting Nameless and Friendless offers one of the most forceful examples of a women artist making a clearly articulated stand on one of the central social issues of the day. The painting is an image of its time, one that expresses the contradictions within Victorian society as well as its appetite for the mawkish. Like a character from a Dickens novel, the distressed woman artist is indeed sentimentalized, but like Dickens, Osborn does this not simply for effect, but to awaken her audience to the real and urgent need for social change.

Additional resources:

*Linda Nochlin, “Why are there no Great Women Artists,” as published in ARTnews, January 1971.

The Governess by Emily Mary Osborne – another painting on the subject of women and work

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

William Morris and Philip Webb, Red House

Cult of domesticity

By the mid-nineteenth century, many people were troubled by the effects that the Industrial Revolution was having on the environment, society at large, and workers employed in factories, concerns that are echoed in today’s environmental movement. The English art critic John Ruskin argued that the inexpensive, factory-made goods flooding the markets had a negative effect on both those who made them and those who consumed them.

Ruskin and others believed that mechanized factory production deprived workers of the personal satisfaction and creativity involved in designing and making an object entirely with one’s own hands. They also believed that people who bought these goods were surrounding themselves with soulless objects that lacked aesthetic value. Thus, their domestic environments were missing the elements of spirituality and refinement that produce healthy, well-rounded citizens.

This was a particular concern in the age of the Victorian “cult of domesticity,” which emphasized the home as a morally uplifting respite from the negative influences of city life. Ruskin and his followers advocated a return to the medieval guild model in which artisans were responsible for handcrafting their works from beginning to end. This produced a sense of pride in the worker and guaranteed quality products for the consumer. William Morris was strongly influenced by Ruskin’s writing and also dedicated to social reform.

Craftsmanship and community

Red House was the home he designed in Bexleyheath, a southeastern suburb of London, England, for his family with the assistance of Philip Webb. Webb and Morris met while working in London for the architect G. E. Street. Webb would go on to be one of the major architects of the Gothic Revival movement in England.

Morris wanted the house to be a place that reflected his ideals and celebrated art, craftsmanship, and community. Morris and Webb collaborated to make the house’s architecture and interior design merge into a unified whole. This would provide the appropriate atmosphere to foster domestic harmony and instill creative energy in its inhabitants and visitors. It was the first home built according to the principles of fine artistry and utility that became the hallmark of the design firm Morris founded with Webb in 1861, as well as the emerging Arts and Crafts movement.

Morris and Webb designed the house in a simplified Tudor Gothic style. The features of this style include historicizing elements such as steep roofs, prominent chimneys, cross gables, and exposed-beam ceilings, all present in Red House. Morris was influenced by Ruskin and other theorists who saw the Gothic as a time of perfection in the craft and building trades, as well as a period of great faith and belief in human dignity. They also viewed the Gothic as a more suitable style for Northern Europe because it originated in France, a northern country, as opposed to the classical forms of ancient Greece and Rome. For Morris and Webb, the adoption of a specifically English form of Gothic architecture seemed natural and appropriate to the site.

A medieval ideal

The use of exposed red brick for the exterior both gave the house its name and reveals the innate beauty of the construction materials. Morris and Webb valued the specific beauty of natural materials, which they saw as far superior to and healthier than industrially produced materials. Red House is L-shaped, with the rooms laid out for maximum efficiency and clarity. The L-shaped plan also allows the house to embrace the gardens as a part of the domestic sphere, as well as creates an asymmetry that is typical of traditional Gothic structures that were built over long periods of time. The concept of an integral whole extended to the interior design as well. Webb, Morris, his wife, Jane, and the painter Edward Burne-Jones all worked together to design everything in the home, from the wallpaper to the stained-glass windows to the built-in cabinets and furniture, so that all celebrated the beauty of nature and the medieval guild ideal.

The house is entered through a large wooden door that leads to a rectangular hallway. A settle Morris decorated with illustrations from the medieval German epic Niebelungenlied is to the right. The hallway is filled with light from the stained-glass windows. The dining room to the right contains the original hutch designed by Philip Webb, which has Gothic trefoil motifs and is painted in “dragon’s blood” (a deep red-brown favored by Arts and Crafts practitioners). The original rustic dining room table remains, along with the decorative arch in the brickwork around the fireplace.

Other original built-in furniture is present in the main living room on the second floor, notably a fireplace painted with Morris’s motto: “Ars Longa, Vita Brevis” (Life is short, art is forever). This room also has paintings by Edward Burne-Jones. Stained glass decorated by Morris, his family and their friends is found throughout the house.

Unfortunately Morris had to sell Red House in 1865 due to financial difficulties. It remained a private residence until 2003, when it was acquired by the National Trust of Great Britain. The architecture of Red House has not been significantly altered, but most of the original furniture is gone and some of the original wall paintings have been covered with modern reproductions of wallpaper Morris produced after he established his design company with Webb and like-minded colleagues. Red House now functions as a museum and is open to the public.