7: Maxine Hong Kingston (1940-)

- Page ID

- 185702

Essay 1

Kingston’s Anthology

Pedro Soares

Born in 1940, Maxine Hong Kingston is identified as the most influential Asian American author of the twentieth century. Throughout her work, especially with “The Woman Warrior” and “China Men”, Kingston demonstrated her legacy to the world by writing about important topics that were not very commonly addressed at the time. As a first-generation Chinese American, Kingston brings personal experience to her writings about gender, race, exclusion, class, and identity. Through fiction, Maxine Hong-Kingston brings similarities from her life, detailing her culture and experiences into stories that represented millions of people and that built her reputation.

By being a first-generation Chinese American, Maxine Hong-Kingston had a different perspective of concepts, experiences, and tradition. In an old, traditional and feudal China, ethics and moral concepts were very distinguished from the pattern that we live in Western civilization, “When Chinese girls listened to the adults talk-story, we learned that we failed if we grew up to be wives or slaves.” (Kingston 4) In her book, “The Woman Warrior”, Kingston addresses some problems involving women's life in Chinese society at the time. By relating into the folklore of Fa Mu Lan, a Chinese warrior that had to pretend to be a man in order to defend her family, Kingston writes about circumstances where women would go through some traumas provoked by the traditional suppression of a patriarchal society, such as “It is more profitable to raise geese than daughters.” (Kingston 43) As many other girls, Kingston grew into this society, repressing their dreams and expectations for life, leading to disappointment.

“When Chinese girls listened to the adults talk-story, we learned that we failed if we grew up to be but wives or slaves. We could be heroines, swordswomen.” (Kingston 1)

As a female protagonist, a warrior and defender of her family, Maxine Hong-Kingston exemplifies the difficulties faced by the woman that faces poverty, war and mostly, cultural restrictions. Following the legend of Fa Mu Lan, Kingston reconstructs the image of a woman within Chinese society, where she brings sensitivity, subjectivity, but overall, strength to the girls that are growing in this pattern, trying to avoid more trauma. According to the Washington Post Book World reviewer William McPherson, The Woman Warrior expresses a terrifying and very literal story of growing up in a vivid and mysterious mix of cultures. Throughout the story, it is evident that Kingston wants to manifest female sensitivity into a traditional Chinese woman and live with a combination of continuity of the Chinese culture and integration of moral concepts to the woman (Kingston 45).

By presenting her autobiography and using history, Kingston explores gender roles in a Chinese-American identity. According to LeiLani Nishime in her analysis of The Woman Warrior, Maxine Hong-Kingston raises questions through mythology about the conception of gender and genre and the notion of public and private in relation to these concepts, especially to the Chinese-American identity.

The main insight behind Maxine Hong-Kingston work is to present to the world the differences, and mainly, the difficulties that other cultures and lifestyles can have in people's lives. The challenge behind some groups within the society in order to achieve some success, and even get their own rights enforced, shows that there is an important and substantial need for change in our daily lives. And with given opportunities, Kingston shows to all cultures and societies that, “Girls are necessary too” (Kingston 25). By understanding the function within the society of every person and group, without repression and favoritism, it is possible to live in a place with glory and success.

Excerpt

“After I grew up, I heard the chant of Fa Mu Lan, the girl who took her father’s place in battle. Instantly I remembered that as a child I had followed my mother about the house, the two of us singing about how Fa Mu Lan fought gloriously and returned alive from war to settle in the village. I had forgotten this chant that was once mine,given me by my mother, who may not have known its power to remind. She said I would grow up a wife and a slave, but she taught me the song of the warrior woman, Fa Mu Lan. I would have to grow up a warrior woman.” (Kingston 4)

Menstrual days did not interrupt my training; I was as strong as on any other day. “You’re now an adult,” explained the old woman on the ɹrst one, which happened halfway through my stay on the mountain. “You can have children.” I had thought I had cut myself when jumping over my swords, one made of steel and the other carved out of a single block of jade. “However,” she added, “we are asking you to put oʃ children for a few more years.” (Kingston 11)

“I hid from battle only once, when I gave birth to our baby. In dark and silver dreams I had seen him falling from the sky, each night closer to the earth, his soul a star. Just before labor began, the last star rays sank into my belly. My husband would talk to mean d not go, though I said for him to return to the battleɹeld.” (Kingston 17)

“My American life has been such a disappointment.” (Kingston 21)

“There is a Chinese word for the female I—which is “slave.” Break the women with their own tongues! I refused to cook. When I had to wash dishes, I would crack one or two. “Bad girl,” my mother yelled, and sometimes that made me gloat rather than cry. Isn’t a bad girl almost a boy?” (Kingston 22)

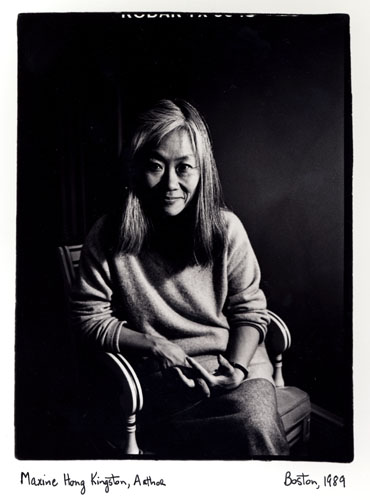

"Maxine Hong Kingston" by Keith Jenkins is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Work Cited

Chow, Karen. "Maxine Hong Kingston: Overview." Reference Guide to American Literature, edited by Jim Kamp, 3rd ed., St. James Press, 1994. Gale Literature Resource Center, link.gale.com/apps/doc/H1420004612/LitRC?u=mlin_c_fitchcol&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=ae416538. Accessed 11 Dec. 2022.

He, Qiong. "Reconstructing the Past: Reproduction of Trauma in Maxine Hong Kingston's The Woman Warrior." Theory and Practice in Language Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, 2019, pp. 131-6.

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior : Memoirs of a Girlhood among Ghosts. Vintage Books, 1989.

Nishime, LeiLani. "Engendering genre: gender and nationalism in 'China Men' and 'The Woman Warrior.'." MELUS, vol. 20, no. 1, spring 1995, pp. 67+. Gale Literature Resource Center, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A17634873/LitRC?u=mlin_c_fitchcol&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=7c5eb2d1. Accessed 11 Dec. 2022.

Essay 2

The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts

Nicki Lovenbury

The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts by Chinese-American author Maxine Hong-Kingston, is an autobiography told by a collection of Chinese folktales. These folktales, or short stories include No Name Woman, White Tigers, Shaman, At the Western Palace, and A song for a Barbarian Reed Pipe. Throughout each story there is a common idea presented that women are essentially useless in Chinese culture, or as Kingston puts it in White Tigers, “It is more profitable to raise geese than daughters” (Kingston 43). In The Woman Warrior, Kingston disputes how these negative ideas about women affect her view of herself and the way she navigates life. She talks mostly about the things she has experienced growing up in her Chinese-American family and the things she was raised to believe. Kingston shares her struggle with self-identity through imaginative storytelling. I chose this selection for the anthology because Maxine Hong-Kingston is a unique writer who shares her experiences genuinely and vulnerably. Overall, Kingston seeks to create a name and identity for herself as a Chinese-American woman that she can share with the world through her writing.

No Name Woman tells the story of Kingston’s aunt who kills herself and her newborn. After her husband leaves for several years, the aunt sleeps with a man and becomes pregnant. The village soon finds out and breaks into her house, destroying everything. The aunt decides to jump into a well, killing herself and the illegitimate child. Kingston’s mother tells her the story as a sort of warning, causing Kingston to fear she may end up like her aunt. The family goes on to pretend her aunt never even existed, not even speaking her name- hence the name of the story; No Name Woman. The next section, White Tigers, draws from a traditional Chinese myth that tells the story of Fa Mu Lan. Fa Mu Lan is a girl who trains for years to become a great warrior, disguises herself as a man, raises an army and wins wars against her enemies and even has a baby along the way. Kingston tells the story as if she is the woman in the story, comparing the journey to her own life in America. This story helps Kingston discover that she has the ability to be as powerful as Fa Mu Lan by using her words to break down traditional stereotypes and gender roles. Shaman is a story about Kingston’s mother, Brave Orchid, who becomes a doctor after the passing of her two children in China. While attending school, Brave Orchid fights and scares away a ghost and when she returns to her village, she is treated as a shaman as a result of this and her healing abilities as a doctor. Towards the end, Kingston explains how her mother thinks work is hard in America and that time passes too quickly. Brave Orchid tells Kingston they no longer own any land in China and will never return, and even asks her to come move back in. Kingston expresses that she is too bothered by ghosts when she is home, and Brave Orchid seems to understand. In the next story At the Western Palace Brave Orchid’s sister, Moon Orchid, comes to visit her and her family in America. Brave Orchid looks down on Moon Orchid because she struggles to perform easy tasks like laundry and dishes, but Brave Orchid wants to help her sister get back on track. Moon Orchid's husband had already moved to America many years ago and now has a new wife and children. Brave Orchid encourages her sister to go and talk to her husband and reclaim her life. This does not end well for Moon Orchid, as her husband says he wants nothing to do with her. Moon Orchid starts to become delusional and fear Mexican ghosts are coming for her. Ultimately, Brave Orchid takes her sister to a mental asylum where she dies. In the last story, A song for a Barbarian Reed Pipe, Kingston starts by explaining how she has always had a hard time communicating. She talks about a quiet Chinese girl in her class who she really did not like. Kingston teases the girl at one point, trying to get her to talk by calling her names, pulling her hair and making the girl cry. She feels like karma punishes her when she mysteriously becomes sick and bed ridden for over a year. She also talks about other individuals who she views as crazy like Crazy Mary and Pee-A-Nah. Kingston herself feels like the crazy person in her family and she creates, in her mind, a list of confessions she would like to tell her mother. In the end, she talks about Ts'ai Yen, who was captured by barbarians and brought back the popular Chinese hymn "A Song for a Barbarian Reed Pipe."

“It is more profitable to raise geese than daughters” (Kingston 43).

For this anthology, I am going to focus on primarily No Name Woman and A song for a Barbarian Reed Pipe. It is clear that the most prevalent topic in each of Kingston’s folktales is her struggle with her identity as a woman in her culture. Brave Orchid is a great cause of these inner battles that Kingston deals with and discusses throughout the book. In No Name Woman, Kingston shares her fears of who she might become. These fears are of course the result of the story her mother told her about her aunt. At one point Brave Orchid even says “what happened to her could happen to you. Don’t humiliate us” (Kingston 13). Kingston’s aunt fell into the connotation that women are useless in Chinese culture. Her family pretended that she never even existed because of her mistakes essentially saying that she is useless and forgettable. Kingston also brought up a point in No Name Woman saying that the child her aunt gave birth to was most likely a girl, so it made her aunt more inclined to kill herself and the child because she knew there was no hope for the child’s future. In Mother Daughter Writing and the Politics of Race and Sex in Maxine Hong Kingston's 'The Woman Warrior, an essay by Wendy Ho, she explains “the Chinese mother and family attempt to instill in the young daughter (even in America) the virtues and habits that are considered ideally feminine in traditional Chinese culture” (Ho). Kingston’s mother instills the fears of becoming a disgrace like her aunt in her mind, putting her in a box and essentially saying that because she is also a woman she could be destined for the same fate. Although Kingston was raised in said traditional Chinese-American family, she never felt like she would grow up to be the person her family expected her to be. In A song for a Barbarian Reed Pipe, Kingston says, “I want to be a lumberjack and a newspaper reporter” (Kingston 196). In the essay Empowerment through Mythological Imaginings in Woman Warrior by Sue Ann Johnston, Johnston speaks on this quote saying, “With her slight physique and her bookish propensities, Kingston is clearly not telling a literal "truth" in this "truthful" confrontation with her mother, but an imaginative one. What Kingston is really saying is that she will not be hemmed in by convention” (Johnston). Kingston repeatedly makes it clear that her gender is not something that defines her or her future. Even considering the fact that Kingston is being raised in America where she doesn’t have to abide by Chinese rules for women as strictly, her family still upholds their traditional views and expects Kingston to follow. In conclusion, Kingston sharing her experiences and becoming a successful author is her way of proving that the social and cultural proposition that women are not even on the same level as geese, is untrue. Kingston does not let society, her family or her culture restrict her and define her role as an individual.

Excerpt from Woman Warrior

I watched our parents buy a sofa, then a rug, curtains, chairs to replace the orange and apple crates one by one, now to be used for storage. Good. At the beginning of the second Communist ve-year plan, our parents bought a car. But you could see the relatives and the villagers getting more worried about what to do with the girls.We had three girl second cousins, no boys; their great-grandfather and our grandfather were brothers. The great-grandfather was the old man who lived with them, as the river-pirate great-uncle was the old man who lived with us. When my sisters and I ate at their house, there we would be—six girls eating. The old man opened his eyes wide at us and turned in a circle, surrounded. His neck tendons stretched out. “Maggots!” he shouted. “Maggots! Where are my grandsons? I want grandsons! Give me grandsons! Maggots!” He pointed at each one of us, “Maggot! Maggot! Maggot! Maggot!Maggot! Maggot!” Then he dived into his food, eating fast and getting seconds. “Eat, maggots,” he said. “Look at the maggots chew.”

“He does that at every meal,” the girls told us in English.

“Yeah,” we said. “Our old man hates us too. What assholes.

”Third Grand-Uncle nally did get a boy, though, his only great-grandson. The boy’s parents and the old man bought him toys,bought him everything—new diapers, new plastic pants—not homemade diapers, not bread bags. They gave him a full-month party inviting all the emigrant villagers; they deliberately hadn't given the girls parties, so that no one would notice another girl.Their brother got toy trucks that were big enough to climb inside. When he grew older, he got a bicycle and let the girls play with his old tricycle and wagon. My mother bought his sisters a typewriter. “They can be clerk-typists,” their father kept saying, but he would not buy them a typewriter.

“What an asshole,” I said, muttering the way my father muttered “Dog vomit” when the customers nagged him about missing socks.

Maybe my mother was afraid that I’d say things like that out loud and so had cut my tongue. Now again plans were urgently afoot to improve my voice. The wealthiest villager wife came to the laundry one day to have a listen. “You better do something with this one,” she told my mother. “She has an ugly voice. She quacks like a pressed duck.” Then she looked at me unnecessarily hard; Chinese do not have to address children directly. “You have what we call a pressed-duck voice,” she said. This woman was the giver of American names, a powerful namer, though it was American names; my parents gave the Chinese names. And she was right: if you squeezed the duck hung up to dry in the east window,the sound that was my voice would come out of it. She was a woman of such power that all we immigrants and descendants of immigrants were obliged to her family forever for bringing us here and for finding us jobs, and she had named my voice. (Kingston 185-6)

"Maxine Hong-Kingston" by Judy Dater is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Work Cited

Ho, Wendy. "Mother Daughter Writing and the Politics of Race and Sex in Maxine Hong Kingston's 'The Woman Warrior,'." Contemporary Literary Criticism, edited by Jeffrey W. Hunter and Polly Vedder, vol. 121, Gale, 2000.

Johnston, Sue Anne. "Empowerment through Mythological Imaginings in Woman Warrior." Contemporary Literary Criticism, edited by Jeffrey W. Hunter and Polly Vedder, vol. 121, Gale, 2000.

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior : Memoirs of a Girlhood among Ghosts. Vintage Books, 1989.