2.3: Researched Argument Essay

- Page ID

- 118499

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)RESEARCH-WRITING PHASE 1 (Source and Topic Selection)

Lesson Introduction

This Canvas assignment is the first phase of a bigger research project that will become a Formal Research Essay; the steps of this research/discussion assignment are just the beginning.

The more thought and effort you contribute to these early phases of the research essay, the better your final product will be (and the less stress you will have in the final phases of the research essay process).

Step 1: Get a New York Times student account

RESEARCH PHASE 2 (Sources, Connections, Your Ideas, DRAFT YOUR THESIS!)

This assignment is the SECOND phase of a multi-week research project. The steps of this assignment are continuing from last week's preliminary research assignment. The more thought and effort you contribute to these early phases of the research essay, the better your final product will be and the less stress you will have in the final phase of the research essay process.

You should have PREVIOUSLY COMPLETED the following from PHASE 1:

- Set up your free student account with the New York Times

- Searched and found a NYT source article that discusses the brain topic you are interested in

- Summarized, Paraphrased, and Quoted parts of the NYT source article you selected

- Developed research questions (these will help guide your research process and discovering some answers will help you develop an argument statement of your own)

Your on-going goals for PHASE 2 of the research project:

- Consider the connections between what you learned in your NYT article and what you learned from The Brain: The Story of You. Look for quotes, vocabulary, and inquiry that link these two sources.

- Consider the connections between your personal experience and knowledge about your topic and what is argued in the sources you have collected so far (your chosen NYT article and David Eagleman’s book).

- Continue researching--collect additional sources to build your background knowledge of the topic and give you an understanding of the existing conversation related to your topic--- you will not need to cite sources that you use only for your own knowledge of the topic.

- Continue researching--collect additional sources and opinions that you think might be helpful to cite in your essay as a quote, paraphrase, or summary.

- Consider a variety of source types and authority as you continue to research your topic and develop your argument. There is a place and a purpose for each source type explained above and you should get comfortable using them all to informally support your knowledge base and to formally establish your arguments in college writing. The DVC library workshop in this unit module discusses some source types and how to select what you need for an assignment.

- Think more about how you plan to join the existing conversation surrounding your topic with a thesis argument of your own creation and from your own perspective.

What to submit for this discussion task

Step 1-- Search and locate the 4-6 sources you plan to use for your researched-argument essay and list your source information in your discussion post.

When you draft and complete your essay assignment, you will need to support your ideas and build your credibility with the use of the following correctly-cited source types:

• One or more formal/authoritative source = The Brain: The Story of You.

• Two or more popular news sources = Your NYT article and at least one more news article that you search and find

•One or more informal source (common web-based or even social-media-based sources that reflect the community opinion and discussion surrounding the topic)

You will need to spend lots of time researching your topic! Read many different types of sources and gather information. Carefully select the sources that you think will be most meaningful to your essay ideas. You will probably not (and should not!) find sources that say your exact thesis statement, but they should relate to the topic and help you explain and support your ideas.

Post what you think will be the best sources that you will want to incorporate into your essay. If you change your mind later as you draft your essay assignment, that is okay.

You will only post a list of your 4-6 sources for step 1; provide the links if possible, so your classmates and I can find and read your interesting finds!

Step 2--Make connections as you synthesize the relevant information on your topic:

Write one paragraph that explains the connection you found between your NYT article (and/or other articles you've discovered in research) and what you learned from The Brain: The Story of You. Explain how the different sources you chose in step 2 will contribute to your discussion of the topic. Do they share similar ideas? Do any show the opposition to the argument? Do they have different perspectives about or different example of the topic?

Post one complete paragraph for step 2!

Step 3--Explain how you plan to join the existing conversation surrounding your topic.

Write one paragraph that explains your ideas and perspective on this topic. Why do you think it's important to know about? Why do you think it's arguable or controversial? What's the opposing side that some people believe and why do you think your argument is important for those people to understand? What is it you really want to say about this topic that contributes a new idea, perspective, example, or importance to the topic?

Post one complete paragraph for step 3!

Step 4--Write a clear thesis statement that says the main idea you want to add to the conversation. Make sure it is arguable/debatable, and that it is in some way connected to the idea of brain research.

As you completed additional research and located your sources for this researched-argument essay, you likely thought more about your topic and the conversation as it exists within the community. Consider the research questions you developed in phase one (and throughout your source collection) and consider if any of those questions can be answered as an effective argument statement for your essay. Decide how you can refine your topic into a potential thesis idea that's specific enough to be interesting, debatable, and thoroughly covered in 1100-1300 words.

Make sure your thesis statement . . .

- is debatable and states a strong argument or angle on the topic.

-

- If there is no-one who would disagree or argue the opposition, then it's not a debatable argument

-

- lets readers know the main idea of the essay.

- is complete and specific enough that readers won't immediately ask: What? How? Why? What do you mean? So what?

-

- For example: a thesis that declares something such as "This leads to positive benefits" is not specific enough because readers will immediately ask, "What benefits do you mean?" Instead, be clear with the precise idea/s your essay will argue.

-

- is not so specific that it cannot be developed and supported well in the length requirements of the assignment.

You will only post a single (strong, arguable, and very well-written) thesis statement for step 4!

RESEARCH PHASE 3 (Outlining and Drafting)

Preparing an Outline or a Graphic Organizer

After you have written a thesis statement and chosen a method of organization, take a few minutes to create an outline or graphic organizer of the essay’s main points in the order you plan to discuss them. This is especially important when your essay is long or complex. Outlining or drawing a graphic organizer can help you see how ideas fit together and may reveal places where you need to add supporting information.

Why and How to Create a Useful Outline

Why create an outline? There are many reasons, but in general, it may be helpful to create an outline when you want to show the hierarchical relationship or logical ordering of information. For research papers, an outline may help you keep track of large amounts of information. For creative writing, an outline may help organize the various plot threads and help keep track of character traits. Many people find that organizing an oral report or presentation in outline form helps them speak more effectively in front of a crowd. Below are the primary reasons for creating an outline.

- Aids in the process of writing

- Helps you organize your ideas

- Presents your material in a logical form

- Shows the relationships among ideas in your writing

- Constructs an ordered overview of your writing

- Defines boundaries and groups

How do I create an outline?

- Determine the purpose of your paper.

- Determine the audience you are writing for.

- Develop the thesis of your paper.

Then:

- Brainstorm: List all the ideas that you want to include in your paper.

- Organize: Group related ideas together.

- Order: Arrange material in subsections from general to specific or from abstract to concrete.

- Label: Create main and sub headings.

Remember: creating an outline before writing your paper will make organizing your thoughts a lot easier. Whether you follow the suggested guidelines is up to you, but making any kind of outline (even just some jotting down some main ideas) will be beneficial to your writing process.

Remember to SANDWICH your quotes. Say what your going to say, Say it (the quote), then say it again. [In other words: Set up your quote, give the quote, and then provide commentary on you quote by answering “why is this quote important?”]

If you have a pragmatic learning style, a verbal learning style, or both, preparing an outline will probably appeal to you. If you are a creative or spatial learner, however, you may prefer to draw a graphic organizer.

Whichever method you find more appealing, begin by putting your working thesis statement at the top of a page and listing your main points below. Leave plenty of space between main points. While you are filling in details that support one main point, you will often think of details or examples to use in support of a different one. As these details or examples occur to you, jot them down under or next to the appropriate main point on your outline or graphic organizer.

Creating an Argument Outline

Although there is no set model of organization for argumentative essays, there are some common patterns that writers might use or that writers might want to combine/customize in an effective way.

For more information on possibilities for setting up ideas in an outline, click here to read Types of Outlines site.) from the Purdue University On-line Writing Lab.

Below are 3 different patterns that you can consider. Also, beneath these are 3 additional outlines that you can choose from if you'd like to print and fill one in.

|

Outline I Introduction/Thesis-Claim (Links to an external site.) Body Paragraph (Links to an external site.) 1: Present your 1st point and supporting evidence. Body Paragraph 2: Present your 2nd point and it's supporting evidence. Body Paragraph 3: Refute (Links to an external site.) your opposition's first point. Body Paragraph 4: Refute (Links to an external site.) your opposition's second point. |

Outline II Introduction/Thesis-Claim (Links to an external site.) Body Paragraph (Links to an external site.) 1: Refute (Links to an external site.) your opposition's first point. Body Paragraph 2: Refute (Links to an external site.) your opposition's second point. Body Paragraph 3: Present your first point and supporting evidence. Body Paragraph 4: Present your second point and supporting evidence. |

Outline III Introduction/Thesis-Claim (Links to an external site.) Body Paragraph (Links to an external site.) 1: Present your first point and it's supporting evidence, which also refutes (Links to an external site.) one of your opposition's claims. Body Paragraph 2: Present your second point and it's supporting evidence, which also refutes (Links to an external site.) a second opposition claim. Body Paragraph 3: Present your third point and it's supporting evidence, which also refutes (Links to an external site.) a third opposition claim. |

3 Additional Outlines that You Can Print and Use:

Basic 5-Paragraph (Argument) Essay Outline: This outline also serves for other essays such as research papers, or the basic 5-paragraph essay. Highlight-and-print outline to fill in.

Another Argument Essay Outline: This outline asks questions that help you critically think about your topic. Highlight-and-print outline to fill in.

Argument/Research Paper Outline Guide: This outline can help guide you through a series of questions. You can highlight-and-print this outline, but it's not a fill-in-the-blank outline; use it as a guide. Many of my students like to use this outline for both research papers and argumentative papers.

RESEACRH-WRITING PHASE 4 (Final Editing, Formatting, and Checking of Your Essay)

Check Your Formatting

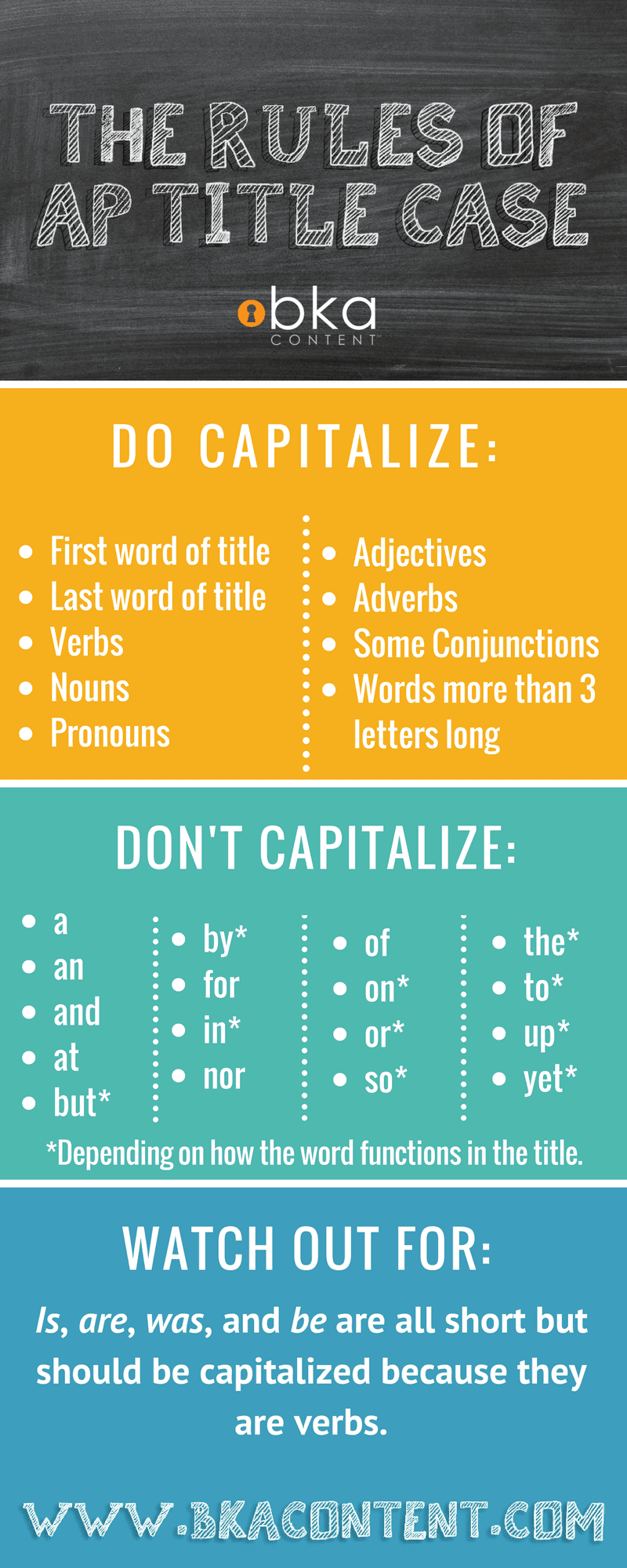

1. Use the rules of title case for your own unique title as well as for the titles of all your sources:

2. Check your heading and page set up for MLA style:

3. Remove any extra line spaces that create a space larger than 2.0:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Avt9fWRGZ_Y

4. Check the OWL Purdue website for MLA guidelines and rules to follow for a college essay

Edit VERY Thoroughly

- Check your essay for errors. Read it carefully sentence by sentence. Look up grammar concerns when you're not sure. Review the rules for writing complete sentences. Check for capital letters and punctuation. A final draft of a college essay assignment should not have any careless errors that you know how to fix yourself.

- Delete any clutter or unnecessary wording in your essay. Read through every sentence and see what you can re-write to be more clear and direct to the point you want to make.

- Have several other students help you find parts of your essay that don't make sense, are missing words, or need more explanation.

- Your final draft will not be ready until you've had many other people read it over and provide feedback and revision suggestions to you. Use the tutoring resources available to you.

Revise Your Essay Draft with this Checklist

- Does this paper fulfill all requirements of the assignment?

- Does this paper have a thesis? Is the thesis specific?

- Does this paragraph have topic sentences at the beginning of each body paragraph? Do the topic sentences both connect to the thesis and introduce what I will be talking about in the paragraph itself?

- Are there paragraphs that seem to be too long or too short? Are the paragraphs relatively similar lengths?

- Have I examined my paper for excess repetition (of words, phrases, sentence constructions)?

- Are there transitions between paragraphs?

- Are there transitions between sentences?

- Does the conclusion do more than simply repeat the introduction, or summarize my argument? Have I extrapolated anything meaningful? Have I explained to my audience why this paper is important to them?

- If quotations have been used, have they been smoothly integrated into the text with my own sentence both before and after the quote, including signal phrases?

- Have I properly formatted quotes over three lines (using indentation)?

- Have I used an appropriate number and variety of sources (per the assignment requirements)?

- Have I documented paraphrases and quotations appropriately, using an approved citation guide (MLA)?

- Does the paper have an original, meaningful title?

- Have I included page numbers?

- Have I maintained consistent use of verb tense?

- Have I used strong verbs?

- Have I used active and passive voice appropriately, given the field of writing?

- Have I read the entire paper aloud, one word at a time, to check for simple errors?

- Have I eliminated unnecessary words?

- Have I carefully proofread the paper for spelling and punctuation?

Check for varied sentence structure and length: With a pen in your hand, read your paper out loud. At the end of each sentence, make a slash mark (/). Look at your sentences: are they very long? Very short? Mix it up!

Check for complete sentences: Starting from the last sentence in your paper, read it backwards, one sentence at a time. This helps you focus on a single sentence. Double-underline the subject and underline the verb for each independent clause. Make sure each subject has a verb. A sentence that starts with for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so, although, as, because, or which runs a high risk of being a sentence fragment, so read it out loud to check if any additional words are needed or if it should be connected to the previous sentence. Be on the lookout for misplaced or absent commas that result in run-on sentences or comma splices.

Check pronouns’ referents: Draw a small square around each pronoun. Draw an arrow to the pronoun’s antecedent/referent. Check that your writing is clear and specific on who or what the pronoun is referring to (Does the reader know who they are? Can the reader easily know what you mean by it?). Check for singular/plural consistency.

Check transitional words and phrases: Draw a wavy line under each transitional word or phrase (moreover, in addition, on the other hand, etc.). You should have some transitions but not too many. Is each transitional word being used appropriately?

Check that you completed all the requirements of the assignment

- Did you create a strong thesis argument that is related to the brain? Make sure your thesis:

-

-

- is debatable.

- states an opinion or provides an angle on the specific topic.

- lets readers know what the main idea of the essay is.

- is specific but not so specific that you were not able to develop it well in the length requirements of the assignment.

- doesn't lead readers to immediately ask "How?" "Why?" or "So what?"

-

- Do you have all the source types USED in your assignment as a paraphrase, summary, or direct quotation and do you clearly introduce the source information in your essay?

-

- One or more formal source = The Brain: The Story of You

- Two or more popular news source = Your NYT article and one more

- One or more informal source = a web-based source that reflect the community discussion of the topic

- Did you cut all clutter and redundancy from your sentences and paragraphs and do you STILL have an essay that falls somewhere between 1100-1300 words (not including the Works Cited page)?

- Did you avoid slang, cliches, and a causal/conversational tone? Did you create a voice and style that is strong and direct? Did you write with a tone that's personal, informative, and appropriate for this college essay assignment?

- Did you create a Works Cited page that follows the rules of MLA documentation.

- Were you careful to avoid ALL TYPES of PLAGIARISM?

Check Your Source Documentation

- Use the OWL Purdue website to look up rules when you have questions

- Use in-sentence information to introduce sources before a summary, paraphrase, or direct quotation:

You cannot use information from any website or published book unless you give the author (or site) credit both inside your text and at the end of your paper. In other words, it is not enough to simply list the sources you used on a Works Cited page or References list.

As your instructor reads your essay, he or she should clearly be able to see which sentences, facts, or sections of your essay came from Source A, Source B, Source C, etc. by looking at your in-text citations.

You can give credit to your sources within your text in two different ways: by using a signal phrase or by simply using an in-text citation.

Signal phrase: signal phrase lets the reader know, right at the beginning of the sentence, that the information he or she is about to read comes from another source.

Example: According to John Smith, author of Pocahontas Is My Love, "Native American women value a deep spiritual connection to the environment" (53).

Notice that since I took a direct quote from John Smith's book, I placed those words in quotation marks. Also notice that because I explained who wrote the book, what book it comes from, and on what page to find the quote in the book, the reader is easily able not only to find the source on his/her own to check my facts, but the reader is also more likely to believe what I have to say now that they know that my information comes from a credible source.

- Use in-text citations (also called parenthetical citations) for page numbers, whenever your source has page numbers. Use this for summaries, paraphrase, and direct quotations.

- Also include the author's last name in the parenthetical citation ONLY if you did not already make it clear with a signal phrase and source introduction in your sentence.

In-Text Citation: Use an in-text citation in situations where you are not quoting someone directly but rather using information from another source such as a fact, summary, or paraphrase to support your own ideas.

Example: When weighing the costs of college with the benefits of getting a degree, it is important to note that “the rate of return on investment in higher education is high enough to warrant the financial burden associated with pursuing a college degree” (Porter 464).

Notice that it's clear within this sentence that I'm referring to a person’s belief or conclusion, but since this person's name does not appear at the beginning of the sentence, I have placed her name and the page number where I retrieved this information in parentheses at the end of the sentence.

- Summarize sources effectively and cite them correctly to avoid plagiarism:

-

- Summarize an article or a larger section of an article whenever you simply want to present the author's general ideas in your essay. Summaries are most often used to condense larger texts into more manageable chucks.

-

How to Write an Effective Summary: Cover up the original article. It is key that you not quote from the original work. Restate what you've read in your own words and be sure to give the author credit using an in-text citation.

Example: Katherine Porter believes that, while getting a college degree can be expensive and time consuming, the benefits greatly outweigh the costs. She discusses the economic, social, and cultural benefits of higher education in "The Value of a College Degree.”

-

Paraphrase sources effectively and cite them correctly to avoid plagiarism:

-

- Paraphrase your sources whenever you believe that you can make the information from a source shorter and/or clearer for your audience. A paraphrase is not an exact copy of the original, so simply changing a few words here and there is not acceptable.

Take a look at these examples:

The original passage from The Confident Student: “Whatever your age, health and well-being can affect your ability to do well in college. If you don’t eat sensibly, stay physically fit, manage your stress, and avoid harmful substances, then your health and your grades will suffer” (Kanar 158).

A legitimate paraphrase: No matter what condition your body is in, you can pretty much guarantee that poor health habits will lead to a lack of academic success. Students need to take time for their physical and emotional well-being, as well as their studies, during college (Kanar 158).

Because the art of paraphrasing is more concise than summarizing, a true paraphrase shows that you as a researcher completely understand the source work.

- Paraphrase your sources whenever you believe that you can make the information from a source shorter and/or clearer for your audience. A paraphrase is not an exact copy of the original, so simply changing a few words here and there is not acceptable.

-

- Quote sources effectively and cite them correctly to avoid plagiarism:

-

- If you need help incorporating your sources into your essay, the first thing you'll need to remember is that quotes cannot stand alone—they can't be placed in a sentence all by themselves. You need to make each quote a part of your essay by introducing it beforehand and commenting on it afterward.

Think of each quote like a sandwich—the quote is the meat on the inside, but before you taste the meat, you must also be introduced to the sandwich by the bread. After you bite down on that meat, you need the other piece of bread to round out the meal.

The top piece of bread will tell us where the quote came from and/or how it fits in with what’s already been discussed in the essay. The bottom piece of bread points out what was important about the quote and elaborates on what was being said.

- If you need help incorporating your sources into your essay, the first thing you'll need to remember is that quotes cannot stand alone—they can't be placed in a sentence all by themselves. You need to make each quote a part of your essay by introducing it beforehand and commenting on it afterward.

-

- The source information in your essay, leads readers to the corresponding source entry in your Works Cited Page, where they will find the rest of the details related to that source:

- The Works Cited page should begin at the top of the page and will become the last page of your essay document. Title it correctly Works Cited and follow all the rules for MLA documentation.

Check Very Carefully that You Have Not plagiarized!

Plagiarism is a hot topic in the academic world, but it applies in all aspects of our lives. In a country and culture that values intellectual property, it is imperative that we are conscious of plagiarism guidelines and standards. The reality is, in many facets of life, when we make mistakes, we can claim ignorance. But when it comes to plagiarizing, there is little slack given; we are all expected to understand plagiarism guidelines and what constitutes a violation.

While plagiarism is never considered acceptable, there are varying levels of severity with different types of plagiarism violations. So are you wondering if you’ve plagiarized? Here’s a quick guide to help show you what constitutes the many areas of plagiarism and how serious each violation is.