1.4.1: Ignatius Sancho

- Page ID

- 138837

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Ignatius Sancho: Reading, literature, and letter writing

https://www.bl.uk/teaching-resources...-late-ignatius

Writer, composer, shopkeeper and abolitionist, Ignatius Sancho was celebrated in the late 18th-century as a man of letters, a social reformer and an acute observer of English life.

Early life

Much of what is written about Sancho’s life is drawn from Joseph Jekyll’s 1782 biography, which accompanied a collection of Sancho's posthumously published letters. In recent years, however, scholars such as Brycchan Carey have questioned the reliability of this biography.[1]

According to Jekyll’s biography, Sancho was born in around 1729 on a slave ship en route from Guinea to the Spanish West Indies. Though this origin story is often repeated, Sancho wrote in his letters that he was born in Africa (Vol. 2, Letter LXVII, 6 June 1780). Sancho grew up an orphan: Jekyll writes that his mother died when he was an infant, and his father committed suicide rather than live in enslavement. Around the age of two, Sancho was taken to London, where he was forced to work as a slave for three sisters at a house in Greenwich. As an adult, Sancho wrote: ‘the first part of my life was rather unlucky, as I was placed in a family who judged ignorance the best and only security for obedience’ (Vol. 1, Letter XXXV, July 1766). During this time he met John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu, who encouraged his education and gave him books to read. After the duke’s death, Sancho ran away from the house in Greenwich and persuaded the duke’s widow to employ him. Sancho would work in the Montagu household for the next 20 years, serving as Mary Montagu’s butler until the Duchess’s death in 1751, and then as valet to George Montagu, 1st Duke of Montagu, until 1773.

Sancho’s marriage, business and music

In 1758 Sancho married Anne Osborne, a West Indian woman with whom he had seven children. After Sancho left the Montagu household, the couple opened a grocery store in Westminster, where Sancho, by then a well-known cultural figure, maintained an active social and literary life until his death in 1780. As a financially independent male householder, Sancho became eligible to vote and did so in 1774 and again just before his death in 1780. He was the first person of African descent to vote in a British general election. He is also the first known person of African descent to have an obituary published in British newspapers.

Sancho was an avid reader and pursued a self-taught education, taking full advantage of the libraries at the Montagu house, as well as its constant stream of highly cultured visitors. When Thomas Gainsborough visited to paint the portrait of the Duchess of Montagu, he also had Sancho sit for a portrait. As well as appearing on the stage, Sancho was particularly productive as a composer of music. He published four collections of compositions and a treatise entitled A Theory of Music.

Letter writing

While working for the Montagus, Sancho also established a wide network of correspondents. He would eventually be best known as an epistolary writer, penning accounts and critiques of 18th-century culture and politics.

In 1766, Sancho struck up a friendship with Laurence Sterne when he sent a letter to encourage the well-known novelist to throw his persuasive and creative power behind the nascent abolitionist cause. The publication of Sterne’s letters in 1775 brought Sancho into the public eye. Sancho wrote letters to the editors of newspapers advocating for the cessation of the slave trade; these letters vividly illustrated the trade's inhumanity for a broad audience, largely people who had never read words written by a black person. In 1780, Sancho penned a dramatic first-hand account of the Gordon Riots, a wave of destructive unrest that swept through London in protest at the repeal of discriminatory laws against Roman Catholics. From his storefront on Charles Street, he wrote to his friend John Spink that he felt compelled to set down even an ‘imperfect sketch of the maddest people that the maddest times were ever plagued with’ (Vol. 2, Letter LXVII, 6 June 1780).

Only after his death did Sancho’s letters reach a large public readership when they were collected and published in 1782 as The Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African. The two-volume collection sold well and delivered to a wide audience Sancho’s reflections on slavery and empire, as well as his own vexed experiences as a highly educated person of African origin living in London towards the end of the 18th century.

- See Brycchan Carey, ‘“The extraordinary Negro”: Ignatius Sancho, Joseph Jekyll, and the Problem of Biography’, British Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 26 (2003) <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/...2003.tb00257.x><https:> [accessed June 2018].</https:>

Further information about the life of Ignatius Sancho can be found via the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Portrait of Ignatius Sancho by Thomas Gainsborough

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/p...nsborough-1768

This is the only known portrait of the writer Ignatius Sancho. It was painted in 1768, when he was employed as a valet by George Brudenell, the Duke of Montagu. Rather than servants’ livery, he wears a gold-trimmed waistcoat, reflecting his valued position within this noble household. Sancho’s gentlemanly posture, with his hand tucked into his waistcoat, conveys a sense of dignity and poise.

Who made and owned the painting?

It was painted by Thomas Gainsborough (1727‒1788), the great portrait artist who had a profitable business in fashionable 18th-century Bath. Gainsborough also painted the Duke and Duchess of Montagu, and they probably paid for this portrait and presented it to Sancho. After his death, Sancho’s daughter Elizabeth sent it as a gift to their family friend, William Stevenson.

A note on the back

Though the picture is full of skill and warmth, it seems to have been done quickly. A 19th-century catalogue describes a note by Stevenson on the back of the canvas, saying ‘This sketch by Mr Gainsborough, of Bath, was done in one hour and forty minutes, November 29th, 1768’.

The portrait served as the basis for an engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi, which appeared in the printed edition of Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho (1782).

Record of Ignatius Sancho’s vote in the general election, October

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/r...n-october-1774

Ignatius Sancho is the first known person of African descent to vote in a British general election. As an independent male property owner, with a house and grocery shop on Charles Street, he had the right to cast his vote for the Westminster Members of Parliament in the 1774 and 1780 elections.

A Correct Copy of the Poll, 1774

In the 18th century there was no secret ballot. Voting was a completely open process, and there was a public record of exactly who voted for whom in each constituency. This is a printed Copy of the Poll taken in October 1774, listing Ignatius Sancho (on p. 15) as a tea dealer in St Margaret’s and St John’s Parish in Westminster, London. Alongside Sancho, over 7,000 other men are recorded in this volume, each with their residence and occupation, from cheesemonger to tailor, bricklayer, gentleman and bookseller.

Who did Sancho vote for in 1774?

There were five Westminster candidates, and each voter could choose two. Sancho supported Earl Percy and Lord Thomas Pelham Clinton, who stood for Lord North’s governing party and won in this constituency. On the other side, Lord Viscount Mahon, Lord Viscount Mountmorres and Humphry Cotes stood for the radical opposition.

The 1780 election: Charles James Fox

In September 1780, Sancho voted again for another winning candidate (this was Sancho’s last vote as he died in December that year). This time he supported George Brydges Rodney and Charles James Fox, a customer in his grocery shop who personally thanked him for his vote and subscribed to his posthumous Letters. Fox criticised Lord North’s punitive policies in America and later became a prominent anti-slavery campaigner. By supporting Fox, Sancho was voting against Thomas Pelham Clinton, whom he had backed in 1774.

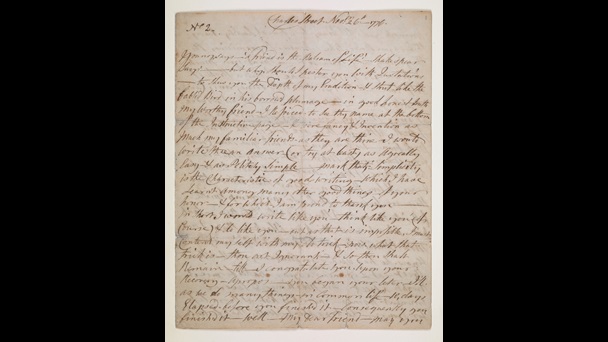

The only surviving manuscript letter of Ignatius Sancho

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/t...gnatius-sancho

These are the only surviving manuscript letters of Ignatius Sancho, the most famous Anglo-African in 18th-century Britain. According to Joseph Jekyll’s 1782 biography, Sancho was born on a transatlantic slave ship and brought to England as a child. He managed to secure help from the noble Montagu family and became a shopkeeper, composer and an accomplished writer.

Who are these letters addressed to?

Twelve of these letters are written from Sancho to his friend William Stevenson (1750‒1821), a publisher and painter who trained under Sir Joshua Reynolds. Three letters are addressed to William’s father, the Reverend Seth Ellis Stevenson (d. 1796). The final seven are written by Sancho’s children, William Leach Osborne (or Billy, 1775‒1810) and Elizabeth (1766‒1837), thanking William Stevenson for his financial support after their parents’ death.

Letters in Sancho’s handwriting (ff. 1r‒23v)

Sancho’s 15 manuscript letters (dated 1776‒80) mention friends from all walks of life – his West Indian brother-in-law John Osborne, the aspiring writer John Highmore, the author Laurence Sterne and the Duke of Queensberry. The letters convey Sancho’s literary sophistication, warmth and gentle humour. He quotes Shakespeare but then laughs at himself for trying to flaunt his ‘erudition, and strut like the fabled bird in his borrow’ d plumage’ (f. 1r). Often he uses a playful, unconventional style, influenced by Sterne’s writing. These letters are peppered with dashes, asterisks, interruptions and self-reflexive remarks on letter writing: ‘I hate fine hands ‒ & fine Language. Write plain honest nonsense’ (f. 16v).

Sancho: Political commentator, family man, shopkeeper

At times, the letters demonstrate sharp engagement with current affairs. He condemns English politicians, saying ‘I am Sir an Affrican – with two ffs – if you please - & proud am I to be of a country that knows no politicians – nor lawyers … nor Thieves’ (f. 17r‒v).

We see Sancho at the heart of his large family, showing love and admiration for his West Indian wife, Anne: she is ‘truly [my] best part – without a Single tinge of my defects’. He gives a poignant description of Anne staying up for nearly ‘thirty nights’ as their five-year-old daughter Kitty is dying (f. 16r).

We also catch frequent glimpses of Sancho’s life as a grocer. He sends Reverend Stevenson ‘Scotch Snuff’, sugar lumps, coffee and ‘the best Turkey Berrys’ (f. 14r‒v). But he also receives generous gifts: ‘Black puddings & Sausages & four of the best pork pyes Ever tasted’ (f. 12v).

Letters from Elizabeth (ff. 24r‒28v; 34r‒v) and William Sancho (ff. 29r‒32v)

The letters from Elizabeth, dated 1818‒19, are very rare examples of writing by a black woman in 19th-century England, a time when most people were illiterate. Though Elizabeth’s handwriting is less self-assured than her father’s, she has clearly received an education. For some reason, one note has been written on her behalf by her cousin (f. 27r‒v). In the last of Elizabeth’s letters (f. 28r), she presents William Stevenson with her ‘dear fathers portrait’ painted by Thomas Gainsborough.

An offprint of a pamphlet about Gainsborough’s portrait is bound with this manuscript (ff. 33r‒v; 35r‒36v).

Facsimile of a letter from Laurence Sterne to Sancho (f. 37r‒v)

In 1766 Sancho wrote to Laurence Sterne – one of his favourite authors ‒ asking him to ‘give half an hours attention to slavery’. This is a handwritten copy of Sterne’s reply on 27 July. Sterne reveals that he is already writing ‘a tender tale’ about ‘a friendless poor negro-girl’ and hopes to weave it into the final volume of Tristram Shandy. Revealing his horror of the slave trade, he says it ‘casts a sad shade upon the world that so great a part of it are … bound … in Chains of Misery’. The two men exchanged many letters and eventually met. Their correspondence was published in a posthumous edition of Sterne’s Letters (1775), and it made Sancho famous. As Vincent Carretta has highlighted, they are ‘the first published challenges to slavery and the slave trade by a person of African descent’.

Further information

A summary of each letter is given in the British Library catalogue. Nine of the letters were published posthumously in Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African (1782) with some variations. In places, the manuscript has been marked up with sections to be cut before publication. All 15 of the letters written by Ignatius Sancho (but not those by his children) are published in Vincent Carretta's 2015 edition.

The manuscript collection also includes the fifth edition of Sancho’s Letters (1803), printed for Sancho’s son William, who became the first black publisher in the Western world. This copy has handwritten notes and an index made by William Stevenson and his son Seth.