10.2: Finding Sources

- Page ID

- 25769

SKILLS TO DEVELOP

- Identify preliminary research strategies (developing a research plan, basic online searching, using Google)

- Identify intermediate research strategies (advanced online searches, finding scholarly sources and primary and secondary sources, librarian consultation)

- Identify advanced search strategies (advanced library searches, library databases, keyword and field searches)

Introduction

Figure 4.2.14.2.1

There are numerous reasons to include research in an academic essay or project.

- Reading what others have written about a topic clearly helps you become better-informed about it.

- Sharing what you’ve learned about the topic in your essay or project demonstrates your knowledge.

- Quoting or paraphrasing experts in the field establishes your own credibility as an author on the topic.

- Responding to what’s already been said on a topic, by including your unique perspective, allows your essay or project to enter the broader conversation, and shape how others feel about the issue.

And, the biggest motivation of all: it’s a requirement for an assignment (because your instructor wants you to do all of those things above).

The writing process is a series of flexible steps that help you break a large project into smaller, bite-size pieces. Research is also a process. It’s not something that can be accomplished well in one single step, but rather done in stages, with time for reflection and analysis in between.

The first part of that process is simply knowing where to look, and that’s what we’ll explore in the following pages.

Preliminary Research Strategies

Figure 4.2.24.2.2

The first step towards writing a research paper is pretty obvious: find sources. Not everything that you find will be useful, and those that are useful are not always easily found. Having an idea of what you’re looking for–what will most help you develop your essay and enforce your thesis–will help guide your process.

Example of a Research Process

An effective research process should go through these steps:

- Decide on the topic.

- Narrow the topic in order to narrow search parameters.

- Create a question that your research will address.

- Generate sub-questions from your main question.

- Determine what kind of sources are best for your argument.

- Create a bibliography as you gather and reference sources.

Each of these is described in greater detail below.

Pre-Research

Figure 4.2.34.2.3 - Books, books, books …Do not start research haphazardly—come up with a plan first.

A research plan should begin after you can clearly identify the focus of your argument. First, inform yourself about the basics of your topic (Wikipedia and general online searches are great starting points). Be sure you’ve read all the assigned texts and carefully read the prompt as you gather preliminary information. This stage is sometimes called pre-research.

A broad online search will yield thousands of sources, which no one could be expected to read through. To make it easier on yourself, the next step is to narrow your focus. Think about what kind of position or stance you can take on the topic. What about it strikes you as most interesting? Refer back to the prewriting stage of the writing process, which will come in handy here.

PRELIMINARY SEARCH TIPS

- It is okay to start with Wikipedia as a reference, but do not use it as an official source. Look at the links and references at the bottom of the page for more ideas.

- Use “Ctrl+F” to find certain words within a webpage in order to jump to the sections of the article that interest you.

- Use Google Advanced Search to be more specific in your search. You can also use tricks to be more specific within the main Google Search Engine:

- Use quotation marks to narrow your search from just tanks in WWII to “Tanks in WWII” or “Tanks” in “WWII”.

- Find specific types of websites by adding “site:.gov” or “site:.edu” or “site:.org”. You can also search for specific file types like “filetype:.pdf”.

- Click on “Search Tools” under the search bar in Google and select “Any time” to see a list of options for time periods to help limit your search. You can find information just in the past month or year, or even for a custom range.

Figure 4.2.44.2.4 - Use features already available through Google Search like Search Tools and Advanced Search to narrow and refine your results.

As you narrow your focus, create a list of questions that you’ll need to answer in order to write a good essay on the topic. The research process will help you answer these questions.

Another part of your research plan should include the type of sources you want to gather. Keep track of these sources in a bibliography and jot down notes about the book, article, or document and how it will be useful to your essay. This will save you a lot of time later in the essay process–you’ll thank yourself!

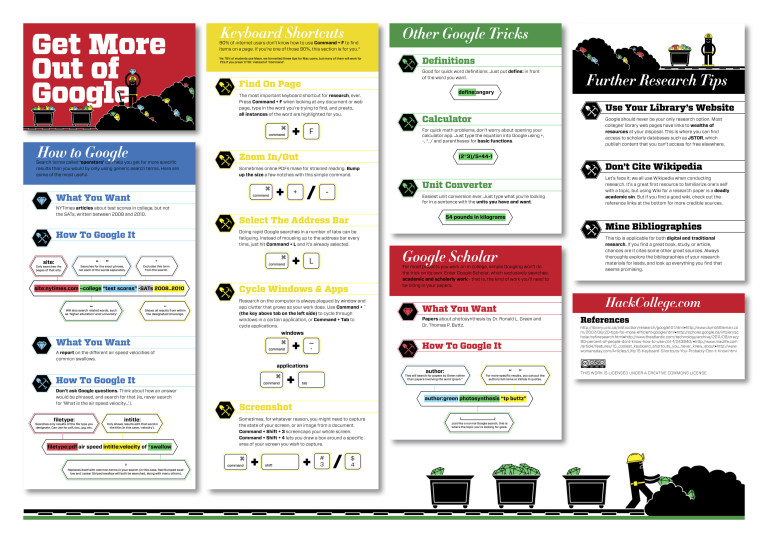

Level Up Your Google Game

Getting More Out of Google

For a visual representation of additional online search tips, click the image below.

Figure 4.2.54.2.5 - Click on this Infographic to open it and learn tricks for getting more out of Google.

Intermediate Search Strategies

“Popular” vs. “Scholarly” Sources

Research-based writing assignments in college will often require that you use scholarly sources in the essay. Different from the types of articles found in newspapers or general-interest magazines, scholarly sources have a few distinguishing characteristics.

| Popular Source | Scholarly Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Intended Audience | Broad: readers are not expected to know much about the topic already | Narrow: readers are expected to be familiar with the topic before-hand |

| Author | Journalist: may have a broad area of specialization (war correspondent, media critic) | Subject Matter Expert: often has a degree in the subject and/or extensive experience on the topic |

| Research | Includes quotes from interviews. No bibliography. | Includes summaries, paraphrases, and quotations from previous writing done on the subject. Footnotes and citations. Ends with bibliography. |

| Publication Standards | Article is reviewed by editor and proofreader | Article has gone through a peer-review process, where experts on the field have given input before publication |

Where to Find Scholarly Sources

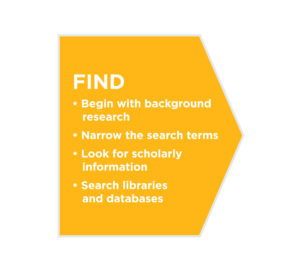

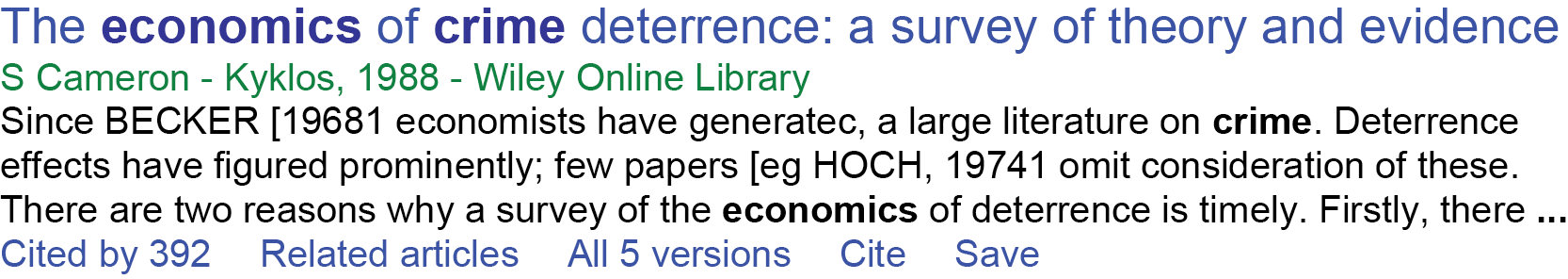

Figure 4.2.64.2.6

The first step in finding scholarly resources is to look in the right place. Sites like Google, Yahoo, and Wikipedia may be good for popular sources, but if you want something you can cite in a scholarly paper, you need to find it from a scholarly database.

Two common scholarly databases are Academic Search Premier and ProQuest, though many others are also available that focus on specific topics. Your school library pays to subscribe to these databases, to make them available for you to use as a student.

You have another incredible resource at your fingertips: your college’s librarians! For help locating resources, you will find that librarians are extremely knowledgeable and may help you uncover sources you would never have found on your own—maybe your school has a microfilm collection, an extensive genealogy database, or access to another library’s catalog. You will not know unless you utilize the valuable skills available to you, so be sure to find out how to get in touch with a research librarian for support!

Primary and Secondary Sources

A primary source is an original document. Primary sources can come in many different forms. In an English paper, a primary source might be the poem, play, or novel you are studying. In a history paper, it may be a historical document such as a letter, a journal, a map, the transcription of a news broadcast, or the original results of a study conducted during the time period under review. If you conduct your own field research, such as surveys, interviews, or experiments, your results would also be considered a primary source. Primary sources are valuable because they provide the researcher with the information closest to the time period or topic at hand. They also allow the writer to conduct an original analysis of the source and to draw new conclusions.

Secondary sources, by contrast, are books and articles that analyze primary sources. They are valuable because they provide other scholars’ perspectives on primary sources. You can also analyze them to see if you agree with their conclusions or not.

Most college essays will use a combination of primary and secondary sources.

Google Scholar

An increasingly popular article database is Google Scholar. It looks like a regular Google search, and it aims to include the vast majority of scholarly resources available. While it has some limitations (like not including a list of which journals they include), it’s a very useful tool if you want to cast a wide net.

Here are three tips for using Google Scholar effectively:

- Add your topic field (economics, psychology, French, etc.) as one of your keywords. If you just put in “crime,” for example, Google Scholar will return all sorts of stuff from sociology, psychology, geography, and history. If your paper is on crime in French literature, your best sources may be buried under thousands of papers from other disciplines. A set of search terms like “crime French literature modern” will get you to relevant sources much faster.

- Don’t ever pay for an article. When you click on links to articles in Google Scholar, you may end up on a publisher’s site that tells you that you can download the article for $20 or $30. Don’t do it! You probably have access to virtually all the published academic literature through your library resources. Write down the key information (authors’ names, title, journal title, volume, issue number, year, page numbers) and go find the article through your library website. If you don’t have immediate full-text access, you may be able to get it through inter-library loan.

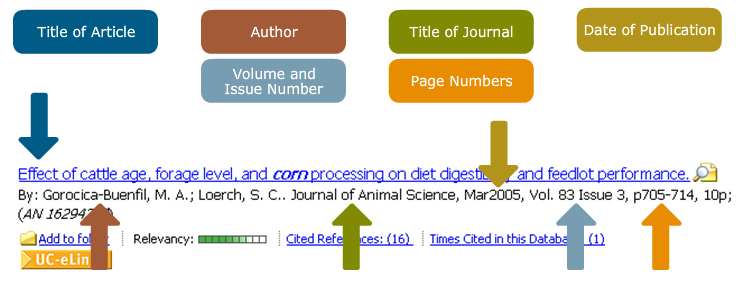

- Use the “cited by” feature. If you get one great hit on Google Scholar, you can quickly see a list of other papers that cited it. For example, the search terms “crime economics” yielded this hit for a 1988 paper that appeared in a journal called Kyklos:

Figure 4.2.74.2.7 - Google Scholar search results.

USING GOOGLE SCHOLAR

Watch this video to get a better idea of how to utilize Google Scholar for finding articles. While this video shows specifics for setting up an account with Eastern Michigan University, the same principles apply to other colleges and universities. Ask your librarian if you have more questions.

Advanced Search Strategies

As we learned earlier, the strongest articles to support your academic writing projects will come from scholarly sources. Finding exactly what you need becomes specialized at this point, and requires a new set of searching strategies beyond even Google Scholar.

For this kind of research, you’ll want to utilize library databases, as this video explains.

Many journals are sponsored by academic associations. Most of your professors belong to some big, general one (such as the Modern Language Association, the American Psychological Association, or the American Physical Society) and one or more smaller ones organized around particular areas of interest and expertise (such as the Association for the Study of Food and Society and the International Association for Statistical Computing).

Figure 4.2.84.2.8

Finding articles in databases

Your campus library invests a lot of time and care into making sure you have access to the sources you need for your writing projects. Many libraries have online research guides that point you to the best databases for the specific discipline and, perhaps, the specific course. Librarians are eager to help you succeed with your research—it’s their job and they love it!—so don’t be shy about asking.

The following video demonstrates how to search within a library database. While the examples are specific to Northern Virginia Community College, the same general search tips apply to nearly all academic databases. On your school’s library homepage, you should be able to find a general search button and an alphabetized list of databases. Get familiar with your own school’s library homepage to identify the general search features, find databases, and practice searching for specific articles.

How to Search in a Database

Scholarly databases like the ones your library subscribes to work differently than search engines like Google and Yahoo because they offer sophisticated tools and techniques for searching that can improve your results.

Databases may look different but they can all be used in similar ways. Most databases can be searched using keywords or fields. In a keyword search, you want to search for the main concepts or synonyms of your keywords. A field is a specific part of a record in a database. Common fields that can be searched are author, title, subject, or abstract. If you already know the author of a specific article, entering their “Last Name, First Name” in the author field will pull more relevant records than a keyword search. This will ensure all results are articles written by the author and not articles about that author or with that author’s name. For example, a keyword search for “Albert Einstein” will search anywhere in the record for Albert Einstein and reveal 12, 719 results. Instead, a field search for Author: “Einstein, Albert” will show 54 results, all written by Albert Einstein.

EXAMPLE 4.2.14.2.1:

This short video demonstrates how to perform a title search within the popular EBSCO database, Academic Search Complete.

EXERCISE 4.2.14.2.1

- Identify the keywords in the following research question: “How does repeated pesticide use in agriculture impact soil and groundwater pollution?”

- When you search, it’s helpful to think of synonyms for your keywords to examine various results. What synonyms can you think of for the keywords identified in the question above?

- Answer

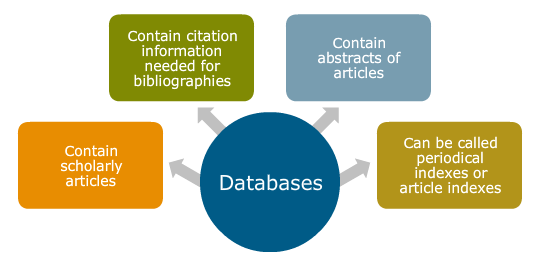

Sometimes you already have a citation (maybe you found it on Google Scholar or saw it linked through another source), but want to find the article. Everything you need to locate your article is already found in the citation.

Figure 4.2.94.2.9 - CC-BY-NC-SA image from UCI Libraries Begin Research Online Workshop Tutorial.

Many databases, including the library catalog, offer tools to help you narrow or expand your search. Take advantage of these. The most common tools are Boolean searching and truncation.

Boolean Searching

Boolean searching allows you to use AND, OR, and NOT to combine your search terms. Here are some examples:

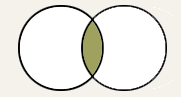

- “Endangered Species” AND “Global Warming” When you combine search terms with AND, you’ll get results in which BOTH terms are present. Using AND limits the number of results because all search terms must appear in your results.

Figure 4.2.104.2.10 - “Endangered Species” AND “Global Warming” will narrow your search results to where the two concepts overlap.

- “Arizona Prisons” OR “Rhode Island Prisons” When you use OR, you’ll get results with EITHER search term. Using OR increases the number of results because either search term can appear in your results.

Figure 4.2.114.2.11 - “Arizona Prisons” OR “Rhode Island Prisons” will increase your search results.

- “Miami Dolphins” NOT “Football” When you use NOT, you’ll get results that exclude a search term. Using NOT limits the number of results.

Figure 4.2.124.2.12 - “Miami Dolphins” NOT “Football” removes the white circle (football) from the green search results (Miami Dolphins).

Truncation

Truncation allows you to search different forms of the same word at the same time. Use the root of a word and add an asterisk (*) as a substitute for the word’s ending. It can save time and increase your search to include related words. For example, a search for “Psycho*” would pull results on psychology, psychological, psychologist, psychosis, and psychoanalyst.