5.3: Evaluating for Credibility

- Page ID

- 258615

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Evaluating for Credibility

Credibility is the degree to which a source can be trusted. Credibility in academic research refers to the trustworthiness and reliability of the sources, data, and findings presented in a scholarly work. It encompasses the accuracy, validity, and integrity of the information, ensuring that it is derived from rigorous methodologies, well-documented evidence, and ethical practices. Credibility is established through peer review, the use of reputable sources, transparency in the research process, and the author's expertise and reputation in the field. A credible academic work enables other researchers to verify and build upon its findings, contributing to the body of knowledge with confidence in its authenticity and reliability.

What are the clues for inferring a source’s credibility? Let’s start with evaluating websites, since we all do so much of our research online. But we’ll also include where to find clues relevant to sources in other formats when they differ from what’s good to use with websites. Looking at specific places in the sources will mean you don’t have to read all of every resource to determine its worth to you.

Criteria for Evaluating Research Findings for Credibility and Quality

Once you pull your resources, you have to evaluate them with a critical eye and a set of criteria to ask yourself: "Is this a valid credible source?" Below is a list of criteria to ask yourself when evaluating a source:

- Author's Background and Expertise 📚

- What are the author's qualifications, academic credentials, and professional experience?

- Is the author recognized as an expert in the field?

- Purpose and Objective 🎯

- What is the purpose of the research? (To inform, persuade, entertain, or sell?)

- Does the research aim to answer a specific question or solve a problem?

- Funding and Sponsorship 💰

- Who is funding or sponsoring the research?

- Is there any potential conflict of interest due to the funding source?

- Publication Source 🏛️

- Where is the research published? (Academic journal, conference proceedings, institutional report, etc.)

- Is the publication source reputable and peer-reviewed?

- Peer Review Status 👩🔬

- Has the research been peer-reviewed by other experts in the field?

- What do the peer reviewers say about the quality and validity of the research?

- Bias and Objectivity ⚖️

- Is there any evident bias in the research?

- Does the author acknowledge and address potential biases?

- Methodology 🧪

- Is the research methodology clearly described and appropriate for the study?

- Are the methods used reliable and valid?

- Evidence and Data Quality 📊

- Is the evidence provided sufficient, relevant, and well-documented?

- Are the data sources credible and accurately cited?

- Consistency and Replicability 🔄

- Are the research findings consistent with other studies on the same topic?

- Can the study be replicated by other researchers to verify the results?

- Clarity and Transparency ✍️

- Is the research clearly written and well-organized?

- Are all aspects of the research process transparent and adequately explained?

- Relevance and Timeliness ⏰

- Is the research relevant to the current state of knowledge in the field?

- How recent is the research? Are the findings still applicable?

- Ethical Considerations 🕊️

- Has the research been conducted ethically, with proper consideration for subjects and data handling?

- Are ethical approvals and consent documented?

- Impact and Citations 🌟

- How often is the research cited by other scholars?

- What impact has the research had on the field?

- Author’s Affiliation 🏫

- What is the institutional affiliation of the author?

- Is the institution reputable and known for quality research?

- Intended Audience 👥

- Who is the intended audience for the research?

- Is the research tailored to an academic, professional, or general audience?

By considering these criteria, we can critically evaluate the credibility and quality of research findings, ensuring they rely on trustworthy and valid sources in their academic work. This might seem like a lot of steps, however, the more you take these steps, the faster you will get at examining your sources until it becomes second nature.

Distinguishing between Information Sources

Information is published in a variety of formats, each with its own special considerations when it comes to evaluation. Consider the following formats.

Social Media

Social media is a quickly rising star in the landscape of information gathering. Facebook updates, Tweets, wikis, and blogs have made information creators of us all and have a strong influence not just on how we communicate with each other but also on how we learn about current events or discover items of interest.

Anyone can create or contribute to social media and nothing that’s said is checked for accuracy before it’s posted for the world to see. So do people really use social media for research? Currently, the main use for social media like tweets and Facebook posts is as primary sources that are treated as the objects under study rather than sources of information on a topic. But now that the Modern Language Association has a recommended way to cite a Tweet social media may, in fact, be gaining credibility as a resource.

News Articles

These days, social media will generally be among the first to cover a big news story, with news media writing an article or report after more information has been gathered. News articles are written by journalists who either report on an event they have witnessed firsthand, or after making contact with those more directly involved.

The focus is on information that is of immediate interest to the public and these articles are written in a way that a general audience will be able to understand. These articles go through a fact-checking process, but when a story is big and the goal is to inform readers of urgent or timely information, inaccuracies may occur. In research, news articles are often best treated as primary sources, especially if they were published immediately after a current event.

Magazine Articles

While news articles and social media tend to concentrate on what happened, how it happened, who it happened to, and where it happened, magazine articles are more about understanding why something happened, usually with the benefit of at least a little hindsight.

Writers of magazine articles also fall into the journalist category and rely heavily on investigation and interviews for research. Fact-checking in magazine articles tends to be more accurate because magazines publish less frequently than news outlets and have more time to get facts right. Depending on the focus of the magazine, articles may cover current events or just items of general interest to the intended audience. The language may be more emotional or dramatic than the factual tone of news articles, but the articles are written at a similar reading level so as to appeal to the widest audience possible. A magazine article is considered a popular source rather than a scholarly one, which gives it less weight in an academic research context, but doesn’t take away the value of these sources.

Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles are written by and for experts and scholars in a field and generally describe formal research studies or experiments conducted to provide new insight on a topic rather than reporting current events or items of general interest. You may have heard the term “peer review” in relation to scholarly articles. This means that before an article is published, it undergoes a review process in order to confirm that the information is accurate and the research it discusses is valid. This process adds a level of credibility to the article that you would not find in a magazine or news article.

Scholarly articles tend to be long and feature specialized language that is not easily understood by someone who does not already have some level of expertise on the topic. Though they may not be as easy to use, they carry a lot of weight in a research context (academic or otherwise), especially if you are working in a field related to science or technology. These sources will give you information to build on in your own original research.

Books

Books have been a staple of the research process since Gutenberg invented the printing press because a topic can be covered in more depth in a book than in most other types of sources. Also, the conventional wisdom for books is that anyone can write one, but only the best ones get published. This is becoming less true as books are published in a wider variety of formats and via a wider variety of venues than in previous eras, which is something to be aware of when using a book for research purposes. For now, the editing process for formally published books is still in place and research in the humanities, which includes topics such as literature and history, continues to be published primarily in this format.

The 5 Ws of Source Evaluation

The five Ws refer to five W questions. You’ve probably explored these W questions in other classes - but here, we’ll apply them to source evaluation.

The beauty of the who, what, when, where, and why questions of information evaluation is that they can be applied to any source. They help you determine whether a source is relevant (meets your information need) and credible (provides reliable, accurate information). Relevant, credible sources are the foundations for strong research papers. Here’s what to ask when you’re looking at a possible source:

- Who is the author of the source? Who published the source? Are they experts?

- What is the purpose of the information source?

- When was the source created? Has it been updated?

- Where can I verify the information?

- Why would I use this source instead of another one?

Let's take a deep dive into the Ws to see how to apply these questions effectively when looking at sources.

Who & What

Who

Who is the author of the source? Who published the source? Are they experts?

You should explore the “who” for every source you’re considering (examples: book, website, article, etc.). Look for author names and credentials (examples: job title or degrees). Look for professional connections that might be notable, such as membership in an organization or employment with an institution.

The who also applies to publishing. Who is responsible for publishing the source? Was it an individual posting on a personal blog? Or was it a book published by a university? The publisher can provide clues about the quality of the source and what kind of review process it’s gone through before it was released to the public.

Where to find information about the author/publisher:

- Books: Look inside the book cover or at the end of the book for a biography of the author. Check the title page or OneSearch record for publisher information.

- Newspapers/Magazines/Journals: Look at the top or bottom of an article for an author’s name and credentials (like their level of education), or information about where they work. Check the top of the page or OneSearch record for the name of the publication.

- Websites: Look for hyperlinks on authors’ names, which often link to short biographies. Look at the top or bottom of the page for an “About” section for publisher information. Don’t assume that the webmaster is also the author of the website’s content.

- Films: Look at the opening or closing credits for writer, director, and performers. For YouTube content, take a look at the channel and look for links to external pages with more information.

For all of these sources, it’s not enough to simply identify the author or publisher - you need to use that information to establish credibility. Questions you might ask yourself:

- Has the author studied and written a lot about the topic, making them an expert?

- Has the author’s life and experiences given them a unique perspective? Consider the fact that there may be different types of experts for any given topic, and the expertise you seek might differ based on the purpose of your research or how you plan to use that particular source.

- Is the publisher well-respected?

If you can’t find answers to these questions inside the source, Google the author/publisher to find any related news, credentials, or affiliations.

What

What is the purpose of the information source?

People can have lots of reasons for creating and sharing information. They may want to use that information to sell you something, to persuade you, to share research findings, to inform or entertain you. This purpose may be obvious or it may be hidden.

For example, the purpose of a well-respected newspaper like the New York Times is to report on current events in a variety of spheres (politics, culture, sports, etc.), and share informed opinions with the public. An academic journal like the Journal of the American Medical Association is designed to share original research and scholarly communication with a professional community. A website promoting tourism in a particular city will provide information portraying that place in the best possible light and carry glowing reviews and advertisements for local restaurants, hotels, and other businesses.

Your job as a researcher is to look at the source, read the language, observe the layout and context, and try to determine the source’s purpose.

When

When was the source created? Has it been updated?

Look for a date of publication or creation as you are selecting sources. Check to see if the source has been updated recently. We use the term currency to describe how up-to-date and timely an information source is. If you can't find a date of publication, look for clues in the text to figure out if the source is old. Old sources might have broken links or might refer to old news or facts.

When evaluating for currency, keep in mind that the ideal date of publication might vary depending on your topic and on the type of source you are using.

Up-to-date information is critical when you research rapidly-changing topics such as scientific information (including medical topics) and technological advancements. However, when you are researching long-standing social or political issues, or topics in history, humanities, and social sciences, the age of sources may not be as important. In these fields, interpretations change over time, but more slowly. These topics often need a balance of older and newer sources. Older sources may help you understand the historical context and reasons why we have current problems. Newer sources may describe recent events and developments related to the issue.

For sources that provide an overview or background information (e.g. encyclopedias) the facts typically remain relevant for decades.

This short video can help you reinforce the things to look for when evaluating "When."

Where

Where can I verify the information?

It may seem obvious, but when you’re selecting sources for a research assignment you want to gather credible information. How can you tell if something is credible and accurate? This is the “Where” - Where can the information be verified? Look for the following clues inside the source:

Source citations:

You are asked to cite sources in your research assignments, and your instructors are probably pretty critical if you don’t do it up to their standards. So turn that idea around. You should be just as critical of the sources you’re using, and make sure authors are telling you where they got their information and how they came to their conclusions.

Just like you, professionals and experts also research, read, and cite from others. When a source includes citations, it’s a clue that the source you are reading is based on more than just one person’s knowledge or opinions.

Citations can be formal (e.g. list of references or endnotes) and include all the details of consulted sources, or they can be informal with a good in-text citation. The best in-text citations give you enough detail to allow you to find the original source (e.g. names and publishers of research studies or hyperlinks to original sources).

But the mere fact that a source includes citations doesn’t automatically mean it’s credible. Take a look at who the author is quoting or referencing and evaluate their authority on the topic.

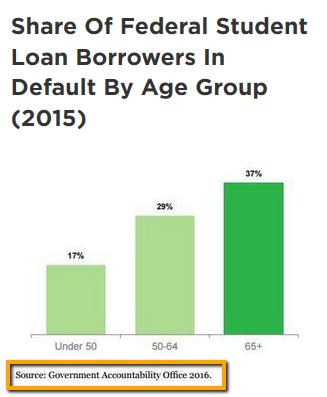

Use of data as evidence:

Data can be a powerful tool to back up claims, persuade, or illustrate a point. Writers often include statistics, charts, graphs, and other forms of evidence to support their arguments or findings. As a savvy researcher, it’s important to look carefully at data and ask questions including:

- How was the data gathered?

- Who gathered the data and is there any evidence of bias or conflicts of interest in the data collection? (e.g. an oil company who funded research showing few emission-related pollutants in the environment).

- Is there sufficient data to support the claims the author is making?

- Is the author “cherry-picking” facts that support their opinions or drawing conclusions that aren’t proven by the data collected?

Agreement among experts:

Another clue for accuracy is whether experts generally agree with the information presented in a source. There will always be hot-button issues like gun violence or immigration about which there is controversy. Even though experts might disagree about the correct solutions or policies, there will be clustering or agreement on certain ideas. If you come across a source that goes against everything you’ve read or know about a topic, apply the 5 Ws to evaluate its credibility.

Peer Reviewed Journals:

Peer-reviewed or refereed sources are articles in academic journals that have undergone an intensive screening process. The articles have been reviewed by a panel of experts in that subject area before they are published. The journal appoints this peer review panel and asks them to look for specific criteria in each article including quality of research, additions to the field of study, and making sure the research abides by the journal’s high standards.

Why

Why would I use this source instead of another one?

Your final evaluation task is to decide whether the source provides relevant information that helps you answer your research question. Keep in mind that you’ll select several sources for your research assignment, and each source should serve a specific purpose.

One source might give you background information to help you understand and focus your topic. Other sources might provide specific evidence in the form of research studies to back up claims you're making. A different source might tell the personal story of someone who has lived and experienced the focus of your topic. Notice that each source has a different purpose and provides a different type of information. By using all these sources in your research paper, you’re able to discuss history, bring in credible evidence, and show the personal side of this issue. The paper will be well-rounded and thorough.

Here are some factors to look at when thinking about relevancy and the reasons why you would use a source.:

Scope:

Scope refers to the amount of information and focus of the source. Think of a telescope. Is the source zoomed in to examine an individual or single element of your topic, or is the source zoomed out to look at the big picture examining the entire topic and the background, history, or other surrounding issues? Is the source short or long? There’s certainly more information in a 300-page book than in a 2-paragraph article.

Perspective:

When preparing a research paper, it can be helpful to select sources that represent different perspectives on an issue. Perspective describes the point of view of the source. Is the source providing an expert’s opinion on an issue, an interview with a victim or survivor of an event, or a researcher’s view based on a new study they completed?

For a controversial issue, look for sources that agree with your position on the issue, and look for a few sources that oppose your position. The best persuasive arguments have good evidence to back up claims, while still acknowledging opposing views on an issue.

Now that we’ve covered all 5 Ws, we can put our evaluation skills together to select the best sources. Measure each source you encounter using the 5 W questions (Who, What, When, Where, Why), and then compare one source against another to select the most relevant and credible information for your topic. Remember that using credible and relevant information will help you be a thorough, thoughtful, and accurate researcher.

Strategic Searching

The key to finding relevant and credible sources related to your topic is sometimes just as simple as searching in the right place. Keep in mind that you’ll have an easier time finding certain types of information using different search tools. Let’s look briefly at the differences between starting your search at Google (or any other search engine) versus starting at your college library using a library database.

|

Types of Sources |

Access |

Authority |

Relevance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

websites, statistics, images, social media, shopping, and more |

Published content like books, journal articles, and news often require payment to access |

Can range from very good to very bad and can be difficult to verify. |

Results are based on search terms and popularity of links. Some searches include irrelevant or duplicate links. |

|

Library Database |

books, ebooks, journal articles, newspapers, magazines, films, and more |

All resources are paid for by the college and provided to students for FREE. |

Authority is easier to confirm. Many sources are published through formal processes including editing before release. Database contains filters to distinguish scholarly material, including limiting results to peer-reviewed journals. |

Relevancy is controlled by using keywords. Users can focus search with limiters (e.g. subject, source type, etc.). Duplicate results are generally removed. |

Knowing When to Stop

For some researchers, the process of searching for and evaluating sources is a highly enjoyable, rewarding part of doing research. For others, it’s a necessary evil on the way to constructing their own ideas and sharing their own conclusions. Whichever end of the spectrum you most closely identify with, here are a few ideas about the ever-important skill of knowing when to stop.

In the Past: Evolving Challenges with Source Credibility

In the past, evaluating the credibility of information sources was more straightforward. Print sources underwent rigorous checks and editorial processes, ensuring a higher level of accuracy and reliability. Conversely, early web sources were often less reliable due to the lack of similar filters and standards. It was generally understood that print sources were more trustworthy, while web content required more scrutiny.

However, the landscape has drastically changed. Many reputable print publishers, including government, university, and peer-reviewed journal publishers, have transitioned to the web, maintaining their high standards for accuracy. Mainstream news organizations also strive to uphold these standards online, knowing their audiences expect reliable information.

Despite this shift, the ease and low cost of web publishing mean that anyone can still publish content online without the rigorous checks associated with print media. This reality makes it increasingly easy to be misled or swayed by inaccurate information if one does not engage in critical thinking. The old markers of quality and credibility are no longer sufficient on their own. Today, it is essential to apply critical thinking skills to evaluate the credibility of all information sources, ensuring they meet the necessary standards of reliability and accuracy.

Fake news refers to deliberately fabricated or significantly misleading information presented as news with the intent to deceive or misinform the public. It often mimics the style and appearance of legitimate news sources to gain credibility and can spread rapidly through digital and social media platforms. From an academic research and critical thinking perspective, fake news undermines the integrity of information dissemination, poses challenges to democratic processes, and necessitates rigorous evaluation and verification methods to identify and combat its effects.

Characteristics of Fake News:

- Deliberate Fabrication:

- Fake news is intentionally created to mislead readers, often for political, ideological, or financial gain. Unlike errors or misinformation that occur unintentionally, fake news is crafted with the purpose of deception.

- Mimicry of Legitimate News Sources:

- Fake news articles often imitate the format, style, and tone of credible news outlets to appear legitimate. This mimicry can include using similar domain names, logos, and layout designs.

- Emotional and Sensational Content:

- Fake news typically contains sensational, shocking, or emotionally charged content designed to provoke a strong reaction and encourage sharing. The use of clickbait headlines and exaggerated claims is common.

- Lack of Verifiable Sources:

- Fake news articles often lack credible and verifiable sources. They may cite non-existent experts, use out-of-context quotes, or present unverifiable data to support their claims.

- Rapid Dissemination:

- The digital age facilitates the rapid spread of fake news through social media platforms, where algorithms prioritize engaging content, regardless of its accuracy. Viral sharing can amplify the reach of fake news quickly.

Lateral Reading & Combating Fake News

One of the best approaches for evaluating sources and identifying fake or misleading news, is lateral reading. Lateral reading is when you compare a source to other sources in order to evaluate its credibility. Through lateral reading you can verify the source's evidence, get better context for the information provided, and find potential biases or weaknesses in its arguments.

Most websites or other sources aren't going to tell you they are biased. Nor will misleading or inaccurate information be openly labeled as such. With the amount of information that we're confronted with every day, it is impossible to fact-check every single piece of information. It's important to prioritize information as you receive it. Some information may be unimportant and doesn't need to be fact-checked.

Some information may sound important, but you may not have time to verify it; in which case you should note it as something that isn't confirmed. But when you are encountering information that you want to digest and put to use at school, work, or share with others; then you should take some time to verify that information. While you can and should look for certain markers of quality (such as author credentials or experience), lateral reading can give you the best understanding of what is and is not accurate.

Reading laterally just means to search and find other sources that can confirm or refute the information you've encountered. For example, if you see a social media post making a claim; you can then search online to find Wikipedia, news articles, and other sources that discuss the same information! Do they sound like they are in agreement? If you look up the author, can you find information that makes them seem unbiased? If there is a claim about specific data or referencing a study, can you find the original source of that data or study?

Changing Standards of Credibility: Two Examples

Anyone can publish a physical book, spend a little money to purchase an ISBN number, and print a lovely hardback book. Likewise, anyone can create a website, make it look professional and attractive, but it could still contain entirely false information. The ease of publishing both in print and online has fundamentally changed how we must approach evaluating credibility.

Example 1: The Print Book with False Claims

Imagine someone decides to write and publish a book claiming that drinking bleach will make you fly and licking dirt will make you invincible. This person spends some money to purchase an ISBN number and prints a beautiful hardback book. There is no magical gatekeeper or wizard in the sky to check the content for accuracy and prevent its publication. The book could then be sold online, in bookstores, or at local markets, potentially misleading readers who might believe these dangerous and false claims simply because they are presented in a professional-looking book.

Example 2: The Deceptive Website

On the other hand, consider someone with a nefarious purpose who wants to mislead people. They create a beautiful, professional-looking website filled with convincing graphics, well-written articles, and attractive design. However, the content is entirely false and intended to deceive visitors.

For instance, the site might promote a fake health remedy claiming to cure serious diseases like cancer or diabetes. The website could feature fabricated testimonials from supposed "patients" who have experienced miraculous recoveries, complete with before-and-after photos that have been altered or taken out of context. The articles on the site might use pseudoscientific language to give an appearance of legitimacy, citing non-existent studies or misrepresenting real research.

To further mislead visitors, the website might include endorsements from fake doctors or experts, complete with photos and biographies that seem credible but are entirely fabricated. The site might also offer a range of products for sale, from supplements to e-books, exploiting the trust of visitors to make a profit.

Such deceptive websites can easily rank high in search engine results or be shared widely on social media, reaching a large audience quickly. Without critical thinking and proper evaluation of the source, visitors might be convinced by the professional appearance and seemingly authoritative content, potentially making harmful health decisions based on the false information provided.

Example: A Misleading Social Media Post

Imagine you come across a social media post claiming that a new agricultural policy will ban the use of all pesticides in the Central Valley, which could have devastating effects on local farms. The post is shared widely, accompanied by alarming images and emotional appeals. The source of the post is a newly created account with a name that sounds official but lacks any credible background information.

To evaluate the credibility of this claim, you should use lateral reading—a strategy where you open new tabs and search for information about the claim, the source, and the context rather than staying on the same page.

Summary for Evaluating Print and Online Sources

These examples highlight the importance of critical thinking in evaluating the credibility of both print and online sources. The traditional markers of quality, such as a polished appearance and professional presentation, are no longer sufficient to determine the reliability of information. Today, it is essential to apply critical thinking skills to scrutinize the author's background, purpose, funding, publication source, and the quality of the evidence presented. By doing so, we can better navigate the vast amount of information available and protect ourselves from being misled by false claims and deceptive content.

Let's Put This Into Practice!

5 Qualifying Factors to Consider: Evaluating Information: Undocumented Immigrant Workers and Worker Rights

When conducting academic research, it is crucial to evaluate the credibility of your sources to ensure the integrity and reliability of your work. This process involves assessing several factors to determine whether a source is suitable for your research purposes. Here are five key factors to consider, using the topic of undocumented immigrant workers and worker rights in an agricultural community in the Central Valley of California as an example:

1. The Source’s Neighborhood on the Web

Example: You find an article discussing the rights of undocumented immigrant workers on a website ending in .com. To evaluate its credibility, you check if the site is linked or referenced by other reputable sources. You discover that the article is frequently cited by educational (.edu) and government (.gov) websites, indicating a credible "neighborhood" on the web. Additionally, if you access this source through an academic database provided by your college library, it adds extra weight to its credibility.

Explanation: Websites associated with educational institutions, government agencies, or reputable organizations are typically more credible. Sources linked by these reputable sites often form a reliable network, enhancing their trustworthiness.

2. Author and/or Publisher’s Background

Example: The author of the article is a professor of labor studies at a well-known university, with multiple publications in peer-reviewed journals on the topic of worker rights and immigration. The article is published by a respected academic journal in labor economics.

Explanation: Understanding the author's qualifications, professional experience, and publication history helps establish credibility. Reputable publishers, particularly academic institutions and scholarly journals, further validate the source’s reliability.

Scholarly Sources: These are written by experts in a field and are intended for an academic audience. They include citations and are often peer-reviewed.

Peer-Reviewed Sources: These have been evaluated by other experts in the field before publication, ensuring the research meets high standards of quality and credibility. In most academic databases there are filters you can turn on to search for just this level of research!

3. The Degree of Bias

Example: While reading the article, you notice that it provides a balanced discussion, acknowledging the challenges faced by undocumented workers and the perspectives of employers. It backs up claims with statistical data and references studies from both government and nonprofit organizations. The language used is factual and avoids overly emotional or persuasive rhetoric.

Explanation: Assessing the degree of bias involves examining how objectively the information is presented. Credible sources strive for balance and support their claims with evidence, avoiding attempts to sway opinion through emotional language.

4. Recognition from Others

Example: The article is cited by several other academic papers, books, and respected news outlets discussing labor rights and immigration policy. It has received positive reviews from other experts in the field and is frequently referenced in policy discussions.

Explanation: Recognition from other reputable sources and experts adds to the credibility of the information. Citations in academic journals and authoritative publications indicate that the source is well-regarded and trusted by the scholarly community.

5. Thoroughness of the Content

Example: The article provides an in-depth analysis of the legal, social, and economic aspects of undocumented immigrant workers' rights. It includes detailed data, case studies, and references a wide range of sources. The bibliography is extensive, allowing you to verify the information and explore further readings.

Explanation: Thorough content demonstrates comprehensive coverage of the topic, supported by detailed analysis and robust evidence. Credible sources cite their references, indicating a well-researched and reliable basis for the information presented.

By applying these five factors—examining the source’s neighborhood on the web, the author’s background, the degree of bias, recognition from others, and the thoroughness of the content—you can effectively evaluate the credibility of information related to undocumented immigrant workers and worker rights. This critical approach ensures that your research is grounded in reliable and trustworthy sources, enhancing the quality and integrity of your academic work.

Application in Research

When evaluating sources for a high-stakes research project, consider all five factors to ensure you are using the most reliable and credible information. For less critical purposes, you might focus on the first three factors—especially the author’s background and the degree of bias.

For example, when researching the health effects of caffeine, a poor research question might be, "Why is caffeine harmful to health?" This question is biased as it assumes caffeine is harmful. A better, neutral question would be, "What are the health effects of caffeine consumption?" This allows for an unbiased exploration of both positive and negative effects.

Using this approach ensures your research is built on a foundation of credible, well-evaluated sources, enhancing the validity and reliability of your findings.

Quality of Sources Info-graphics:

Both Figures: Source Quality Infographic 1 & 2, created by Rachel Fleming, under the CC BY NC SA license.

Summary

By thoroughly evaluating the credibility of your sources through these five factors—web neighborhood, author background, degree of bias, recognition from others, and thoroughness of content—you can ensure the integrity of your research. This critical thinking approach is essential for academic success and for contributing valuable, reliable knowledge to your field.

Language & Definitions in Research You'll Come Across:

Overview of Research Designs

Research designs serve as the blueprint for your study, guiding the collection, measurement, and analysis of data. The main types of research designs include:

- Qualitative Research: Focuses on understanding phenomena from a subjective perspective through interviews, focus groups, and content analysis. It is ideal for exploring complex issues, understanding behaviors, and developing theories.

- Quantitative Research: Emphasizes objective measurement and statistical analysis of data collected through surveys, experiments, or secondary data. It is suitable for testing hypotheses, examining relationships, and making predictions.

- Mixed Methods Research: Combines both qualitative and quantitative approaches to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research problem. It is useful for validating results, providing multiple perspectives, and addressing complex research questions.

Research Methodologies

Methodologies refer to the overall strategy and rationale behind your research approach. The primary methodologies include:

- Descriptive Methodology: Aims to describe characteristics of a population or phenomenon, answering the "what" rather than the "why." It includes surveys and observational studies.

- Experimental Methodology: Involves manipulating one variable to determine if changes in one variable cause changes in another. This methodology is highly controlled and often used in scientific research to establish causality.

- Correlational Methodology: Examines the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them, helping to identify patterns and predict trends.

- Case Study Methodology: An in-depth exploration of a single case or a small number of cases, providing detailed insights into complex issues in real-life contexts.

Data Collection Methods

Data collection methods are the tools and techniques used to gather information for your research. These methods include:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Structured instruments used to collect quantitative data from large groups of respondents efficiently.

- Interviews: Can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured, allowing for in-depth qualitative data collection through direct interaction with participants.

- Observations: Involves systematically recording behaviors or events as they occur in natural settings, useful for both qualitative and quantitative research.

- Experiments: Controlled studies where variables are manipulated to observe their effects, providing high levels of internal validity.

- Document and Content Analysis: Analyzing existing texts, documents, or media to extract meaningful information, commonly used in qualitative research.

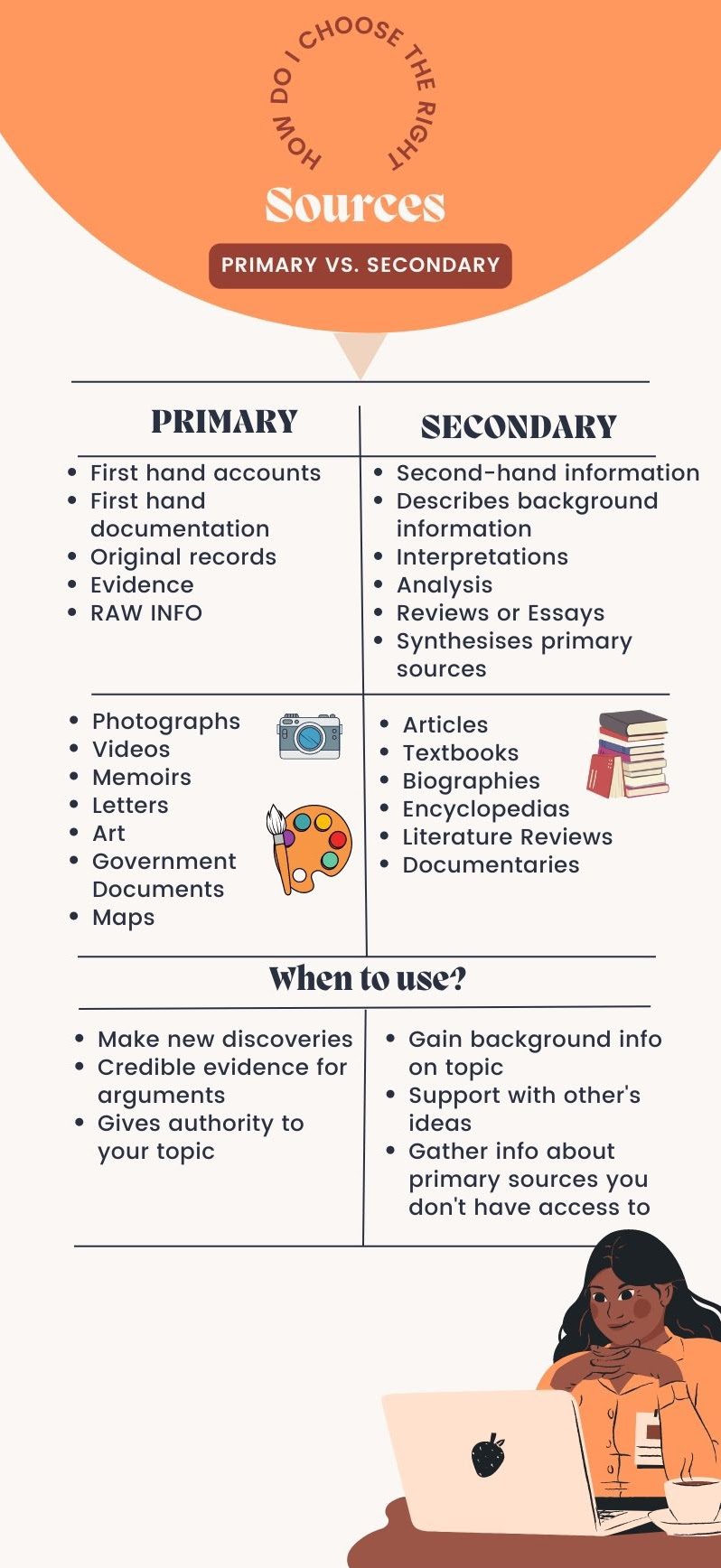

Primary vs. Secondary Sources

Primary Source: A primary source is an original, first-hand account or direct evidence concerning a topic or event. These sources are created by witnesses or first recorders at the time the events or conditions occurred and have not been interpreted or edited by others. They provide direct, unmediated information and include a wide range of materials such as: Historical documents (e.g., letters, diaries, official records); Original research reports (e.g., journal articles presenting new data); Artistic works (e.g., paintings, music, films); Artifacts (e.g., tools, clothing, objects); Interviews and speeches; Photographs and videos; Raw data and statistics; Manuscripts, archives, and original documents; Clinical trial results and scientific experiments; Eyewitness accounts and personal narratives; Records of organizations, government publications, and legal documents.

Secondary Source: A secondary source interprets, analyzes, or summarizes primary sources. These sources are one step removed from the original event or experience and provide second-hand accounts or evaluations. They often synthesize multiple primary sources to present an overview or argument. Secondary sources are created after the fact, often by scholars or experts who have studied primary sources extensively, providing context, commentary, and scholarly analysis such as: Review articles and literature reviews; Biographies; Textbooks and reference books; Critiques and commentaries; Documentaries and history books; Newspaper articles analyzing past events; Academic journal articles reviewing previous research; History books analyzing historical events; Critical essays and literary analysis; Encyclopedias and handbooks summarizing existing knowledge; Media reports providing analysis and context.

Understanding the distinction between primary and secondary sources is crucial for conducting thorough and credible research, as it helps determine the originality and reliability of the information.

Figure: Primary vs. Secondary Source Infographic, created by Rachel Fleming, under the CC BY NC SA license.

Attributions

The content above was assisted by ChatGPT in outlining and organizing information. The final material was curated, edited, authored, and arranged through human creativity, originality, and subject expertise of the Coalinga College English Department and the Coalinga College Library Learning Resource Center and is therefore under the CC BY NC SA license when applicable. To see resources on AI and copyright please see the United States Copyright Office 2023 Statement and the following case study on using AI assistance but curating and creating with human originality and creativity.

Images without specific attribution were generated with the assistance of ChatGPT 2024 and Canva and are not subject to any copyright restrictions, in accordance with the United States Copyright Office 2023 Statement.

All original source content remix above came from the following open educational resources:

This section was remixed by WHCCD Library, original sources remixed from Daniel Wilson at Moreno Valley College 5.3: Evaluating for Credibility shared under a CC BY 4.0 license

4: Evaluating Sources is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

This chapter was compiled, reworked, and/or written by Andi Adkins Pogue and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Original sources used to create content (also licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0):

Bond, Emily. (2018). Evaluate the date [Video file]. https://youtu.be/jAfGCfWJfgo

Evaluate: Assessing your research process & findings. (2016). In G. Bobish & T. Jacobson (Eds.), The information literacy user's guide. Milne Publishing. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/chapter/evaluate-assessing-your-research-process-and-findings/

Los Rios Libraries. (2020). Evaluating and selecting sources. Los Rios libraries information literacy tutorials. https://lor.instructure.com/resources/44fe428e10b347bea9892a63482f55fd?shared