13.7.16: Britain in the 18th century

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 88735

British art: 18th century

The British avoid a revolution, engage in the slave trade, build a global empire, and begin the industrial revolution.

1700 - 1800

Wren, Saint Paul’s Cathedral

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Christopher Wren, Saint Paul’s Cathedral, begun 1675, completed 1711, London

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

William Hogarth

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress

by SOPHIE HARLAND

Sex, booze and 18th-century Britain

If you ever needed proof that the sex, booze and a rock’n’roll lifestyle was not a twentieth century invention, you need look no further than the satirical prints of William Hogarth. He held up a moralizing mirror to eighteenth-century Britain; the harlots, the womanizers—even the clergy could not escape. Hogarth’s prints play out the sins of eighteenth-century London in a kind of visual theater that was entirely new and novel in their day.

The first example of these prints, which Hogarth himself termed ‘modern moral subjects’, was A Harlot’s Progress. In this series, we meet the fresh faced Moll Hackabout as she arrives for the first time in London. Moll is soon preyed upon by a brothel keeper and she descends into prostitution. The tale ends with her premature death from a sexually transmitted disease, aged just twenty-three. Despite its dark subject matter A Harlot’s Progress was a huge success. These prints reference characters types who were well known to their contemporary London audience. For example Moll’s madam was the real-life Elizabeth Needham, keeper of an exclusive London brothel and her first patron, the renowned love-rat and convicted rapist, Colonel Francis Charteris.

A Rake’s Progress

These sly nods to the bad guys of the day not only made the prints hugely relevant and enjoyable to their target audience but it also made them incredibly popular. A Rake’s Progress (1735) was Hogarth’s second series and proved to be just as well loved. The main character is Tom Rakewell—a rake being a old fashioned term for a man of loose morals or a womanizer. Tom’s name is intentionally general and in a modern equivalent, he might be called ‘Mr. Immoral.’ Tom is not unique, he could be any number of people in eighteenth-century Britain.

The series opens with a chaotic scene: Tom’s father, who was a rich merchant, has died and Tom has returned from Oxford University to collect and spend his late father’s wealth. He also wastes no time in rejecting his pregnant fiance, Sarah Young, by attempting to pay her off. Hogarth laces all his prints with clues to help us decode the scene. Here we can see Sarah sobbing into a hankie whilst holding her engagement ring in her hand. Her mother stands behind her angrily clutching the love letters Tom once wrote to her daughter and he holds out a handful of coins in an attempt to get rid of them. Sarah pops up throughout these prints representing a more wholesome life that he could have had.

A fashionable life

By the next scene (“Surrounded by Artists and Professors,” above) Tom has already moved from his cozy, if slightly shabby family home into his new bachelor pad surrounded by a dance master, a music teacher, a poet, a tailor, a landscape gardener, a body guard and a jockey all offering their services to help Tom complete his fashionable lifestyle. He is dressed in his nightclothes indicating that he has just woken: those who wish to exploit his new found wealth are wasting no time.

Tom’s fashionable life also comes with fashionable vices and soon we see him in the Rose Tavern with a group of prostitutes (see “The Tavern Scene,” below). He sits on the lap of one who caresses him with one hand whilst robbing him of his watch with the other. Portraits of Roman Emperors hang on the wall behind them but the only one that has not been defaced is Nero’s. This is perhaps hard for a modern audience to identify but there would have been a significant number of Hogarth’s classically educated audience who got the gag: Nero was a corrupt womanizer who fiercely persecuted Christians. To the very classically aware Georgians (George II was then King) the message was clear, Christian morals are not to be found here.

A decadent decline

Tom’s decadent lifestyle does not last for long and by the third scene his sedan chair is intercepted by bailiffs as he is en route to the Queen’s birthday party. It is at this point that our heroine Sarah Young comes to the rescue. She is now working as a milliner and kindly pays Tom’s bail. Although Sarah has saved Tom from the bailiffs, she cannot save him from himself. By the next scene he is marrying a wealthy old hag. The old woman’s eyes lust eagerly towards the ring and Tom’s towards her maid. In the background Sarah Young and her mother struggle to voice their objections but are held back by some of the guests.

Tom is wealthy again but he is no better with his money now than he was last time and soon he is on his knees in a gambling den having just squandered the lot (see “The Gaming House,” below). Excessive gambling was a real problem in the eighteenth century and whole family fortunes could be lost in one evening. Later in the century, George III’s son, who later became George IV, had to ask Parliament for money to help him pay off his gambling debts. It was given to him but it was not long before he needed even more.

Debtors’ prison

Like so many others in eighteenth-century Britain, Tom finds himself in debtors’ prison, quickly coming to the end of his tether. On the one side his wife derides him for squandering their fortune, on the other the beer-boy and the jailer harass him to settle his weekly bill. Sarah Young, who has come to visit Tom with their child, has fainted on seeing him in this hopeless situation. This must have been very personally relevant for Hogarth as his father spent much of his childhood in a debtors’ prison.

My favorite part of the series is played out in the background of this scene. Tom’s fellow inmates are trying various schemes to get enough money to buy their freedom. However, their choice of projects cleverly illustrate just how impossible it was to get out of debt in Georgian Britain. One man is attempting to turn lead into gold while the other is working on solving the national debt crisis. Even Tom has written a play, though we can clearly see a rejection letter for it lying on the table.

Bedlam

The stresses of the previous scene have proven to be more than Tom can bear and in the final scene he is found languishing in bedlam—London’s notorious mental hospital (see “The Madhouse,” above). The mark on his chest suggests that he has stabbed himself in a failed suicide attempt. Fashionable young women, the likes of which Tom would have socialized with just a short while ago, observe the scene in amusement. All that he has left is the company and care of the faithful Sarah Young.

Why so popular?

One answer is that it appealed to the contemporary concern about people from the middle classes who tried to live like aristocrats. This was a popular issue at this time as the merchant trade was creating social mobility on a scale never seen before. However if we scratch the surface of A Rake’s Progress we can see that a number of different types of people implicated. For example, Tom was on his way to the Queen’s birthday party when he was stopped by bailiffs and therefore his lifestyle is actually being encouraged and supported by aristocrats. In A Rake’s Progress, everyone from the Queen to the priest that performs his marriage of convenience, to common prostitutes, are part of the problem.

But it is not just Hogarth’s ‘take no prisoners’ approach to social commentary that made him so popular. Printed satire was actually already very common place and central London was full of bookshops and print sellers that displayed this kind of work. What Hogarth did do that was so completely novel was to tell a story through pictures, A Rake’s Progress is like a story board for a play. In fact, Hogarth’s series were adapted into plays and pantomimes during his lifetime. His visual drama offered his audience a new way to enjoy satire. It is for this reason that to find comparisons and inspirations we should be looking at authors such as Hogarth’s friend and fellow moralizer, Henry Fielding or Jonathan Swift—author of Gulliver’s Travels, rather than contemporary artists. The title A Rake’s Progress was referencing John Bunyan’s The Pilgrims Progress. We can be quite sure that most people would have gotten this reference as it is thought that, at this time, this was the most read book in Britain after the Bible. Hogarth successfully borrows from popular culture in order to express complicated ideas through an enjoyable and totally accessible story. Of course Hogarth wasn’t the first to do this, but he did it so well, he is celebrated to this day.

William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode, c. 1743, series of six paintings, oil on canvas, 69.9 x 90.8 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Hogarth’s series consists of six paintings which served as models for the engravings: 1. The Marriage Settlement, 2. The Tête à Tête, 3. The Inspection, 4. The Toilette, 5. The Bagnio, 6. The Lady’s Death.

Thomas Gainsborough, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by DR. ABRAM FOX

Money. Possessions. Power.

The same materialistic ideals which drive many men and women today have performed the same function throughout history. Those in positions of power often chose to commemorate their status through images. Some purchase works of art by famous artists to demonstrate their wealth, while others commission portraits of themselves as reminders of their prestige.

A young couple in the middle of the eighteenth century, Robert Andrews and Frances Andrews, opted for the second option to celebrate their marriage and subsequent combination of their families’ fortune. To depict their increased status, the Andrews’ commissioned a relatively unknown painter named Thomas Gainsborough to paint their portraits. Little could they anticipate that within a few decades it would be the artist, and not the subjects, that would make their portrait famous.

A conversation on canvas

Gainsborough’s portrait of the newly-married Robert and Frances Andrews is typical of the genre of “conversation pieces;” informal group portraits which gained popularity in the middle of the eighteenth century in England. Unlike the formal, straightforward portraits which characterized earlier periods and locations, the “conversation piece” usually presented a small group of individuals in an outdoor space, engaged in discussion and unaware of the viewer’s presence. Mr. and Mrs. Andrews diverts from that tradition, as its sitters are clearly reacting to Gainsborough’s presence, but their relaxed poses and location in the English countryside connects them to the “conversation piece” tradition.

At the time Gainsborough executed this painting, he was a 23-year-old emerging artist working in city of Ipswich in the rural English county of Suffolk. As a teenager he served an apprenticeship in London and also received instruction from Hubert-François Gravelot, a popular Rococo engraver working in England’s capital city. In 1749 Gainsborough moved with his wife to Ipswich, 70 miles from London and just 20 miles from his birthplace of Sudbury, in Suffolk County. Robert Andrews and his future wife, then known as Frances Carter, also grew up in Sudbury, in much wealthier families. In his portrait of the pair, Gainsborough captures the barely-veiled disdain in Frances Andrews’ eyes and her wry smile. She and her husband are well aware that the portraitist, whom they would have known since childhood, is well below them on the social ladder.

Love of landscape

Following the “conversation piece” tradition, Gainsborough includes a landscape in his painting. However, he provides a much greater view of rural England than might be expected from such a work. Mr. and Mrs. Andrews pose on the left half of the canvas, rather than directly in the middle as was typical in a straightforward portrait. On the right side, Gainsborough gives equal attention to the grounds of The Auberies, the Andrews’ estate in Sudbury.

The couple is located on the edge of a field of wheat, and fenced in cattle populate the middle ground to the left while sheep graze to the right of the pair. Through the implementation of modern agricultural techniques and technology, Mr. Andrews has brought the land under his control. His pose is meant to suggest that his work is done and he can now relax and hunt with his dog, although he doesn’t look very comfortable holding his rifle.

The attention Gainsborough lavishes on the rolling English countryside reflects his lifelong love for nature. Although he became famous as a portrait painter, Gainsborough insisted throughout his life that landscape painting was his true calling, and he considered himself a landscape painter rather than a portraitist. He spent most of his career outside of London, the center of the English art world. After leaving Ipswich a decade after painting Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, Gainsborough set up shop in the resort city of Bath, where his delicate and sensual portraits defined the Rococo fashion in England in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Rococo in England

The Rococo was a French style, imported by foreign artists like Hubert-François Gravelot and by English collectors. In the early 1700s England did not have a strong painting tradition, and its most famous artists were international painters who traveled to London to take advantage of that fact. Gainsborough looked to the frivolous, playful paintings being commissioned by French aristocrats, and applied their delicate style to slightly more reserved and contained subjects.

Mrs. Andrews’ dress possesses the pastel colors and delicate lace of more erotic French works like Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing. Her dress and Mr. Andrews’ shirt glimmer in sunlight, despite the overcast sky. Mrs. Andrews sits on a bench that is entirely too elaborate to sit exposed in the middle of a wheat field. Both figures are pale and lithe, reflecting the upper class privilege of not having to work for a living. Their expansive estate functions as an ostentatious demonstration of their wealth: it continues as far as the eye can see.

A mysterious absence

Although the Andrews purchased their conversation portrait from Gainsborough, something is missing from the work. Bare canvas surrounds Mrs. Andrews’ hands, folded in her lap. No one knows exactly what Gainsborough intended to paint in that space, if he intended to paint anything at all. Some scholars have suggested that Mrs. Andrews was meant to hold a dead game bird, the result of a successful hunting trip by her husband. Such an inclusion would emphasize the couple’s control over their land, but a bloody animal would ruin Mrs. Andrews’ elaborate dress, and therefore seems unlikely.

Another possibility for Mrs. Andrews’ lap is that the blank space was intended for a baby. Regardless of what was meant to go in that spot, Gainsborough never added it in. Modern scholars consider the painting to be “unfinished,” but we’ll never know what the original finished work was to look like, or if its current state was as “finished” as Gainsborough and the Andrews wanted.

Joseph Wright of Derby, A Philosopher Giving a Lecture at the Orrery

by DR. ABRAM FOX

Two young boys, gazing over the edge of the contraption in playful wonder. A teenaged girl, her arms resting on the machine, in quiet contemplation. A young man shielding his eyes from the brilliance of the light emanating from the center, and a young woman staring unblinkingly. A standing man taking copious notes on the proceedings. Another man leaning back in his seat, listening intently to the gray-haired lecturer, captivating his audience like a magician.

A key idea of the Age of Enlightenment—that empirical observation grounded in science and reason could best advance society—is expressed by the faces of the individuals in Joseph Wright of Derby’s A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery.

The Age of Enlightenment

Wright’s painting encapsulates in one moment the Enlightenment, a philosophical shift in the eighteenth century away from traditional religious models of the universe and toward an empirical, scientific approach. It is important to note the term given this new way of thinking. “Enlightenment” indicates an active process, undertaken by an individual by group.

The age of Enlightenment is most closely associated with scientists and inventors, but writers and artists also played major roles. They helped spread enlightenment concepts via the written word and printed image, and inspired others to think rationally about the world in which they lived. The provincial English painter Joseph Wright of Derby became the unofficial artist of the Enlightenment, depicting scientists and philosophers in ways previously reserved for Biblical heroes and Greek gods.

Joseph Wright of Derby

Joseph Wright of Derby was born in the town of Derby in central England, and save for short stints in Liverpool and London, lived in that city his entire life. He was known even during his lifetime as Joseph Wright of Derby, to distinguish him from another artist of the same name. Even though Wright of Derby was the more talented of the two, he was stuck with the geographical identifier on his name.

Other than Thomas Gainsborough, who spent much of his career in the high-society resort town of Bath, Wright was the most prominent English painter of the eighteenth century to spend the majority of his career outside of London. Operating without the constraints of the mainstream London art world, Wright was free to explore a general interest in science with his friends, a group that included Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles) and other members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, an informal learned society which met to discuss scientific topics of the day.

Wright was known for his deft depiction of the contrasts between light and dark, also known as chiaroscuro, and his unflinching portrayal of the true personalities of his subjects. This trait caused his downfall when he attempted to work as a portraitist—few wanted a portrait, warts and all.

The intensity of scientific discovery

In the 1760s Wright began to explore the traditional boundaries of various genres of painting. According to the French academies of art, the highest genre of painting was history painting, which depicted Biblical or classical subjects to demonstrate a moral lesson. This high regard for history panting was adopted by the British—Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe is a prominent example.

Wright took this noble, aggrandizing method of portraying events and applied it to a composition showing a contemporary subject in A Philosopher Lecturing at the Orrery. Rather than a moral of leadership or heroism, this painting’s “moral” is the pursuit of scientific knowledge. With its collection of non-idealized men, women, boys, and girls informally arranged in a small physical space around a central organizing point, Wright’s painting mimics the compositional structure of a conversation piece (an informal group portrait) like Zoffany’s Gore Family (above), but with the dramatic lighting and scale expected from a major religious scene.

In effect, A Philosopher Lecturing at the Orrery does depict a moment of religious epiphany. Much like the central figure in Caravaggio’s Calling of Saint Matthew (below), the figures listening to the philosopher’s lecture in Wright’s painting are experiencing conversion…to science.

Heroizing the search for knowledge

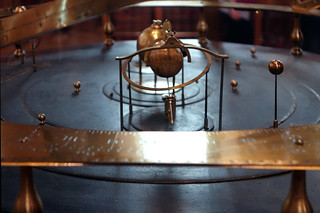

An orrery is a mechanical model of the solar system, a miniature, clockwork planetarium. Each planet, with its moons, is a sphere attached to a swing arm which allows it to rotate around the sun when cranked by hand. When in motion, the orrery depicts the orbits of each planet, as well as their relative relationship to each other. The orrery depicted by Wright has large metal rings which can simulate eclipses, and give the model a striking and exciting three-dimensionality.

Although each of the figures in the painting is clearly modeled on a specific person, Wright’s work was not meant to be a conversation piece in the eighteenth century sense of the word, and so we can only guess at the identities of each person. Most likely the man standing and taking notes is Wright’s friend Peter Perez Burdett, and the man seated at the far right may be Washington Shirley, 5th Earl Ferrers, the initial owner of the work.

Several identities have been proposed for the philosopher delivering the lecture. The most tempting theory is that his face is modeled on that of Sir Isaac Newton, the great English scientist whose work helped herald in the Enlightenment. Another possibility is that it is a member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham.

The events depicted, although exciting, do not give A Philosopher Lecturing at the Orrery its high dramatic impact. That responsibility falls on the paintings strong internal light source, the lamp that takes the role of the sun. Wright mimics Baroque artists like Caravaggio, who inserted strong light sources in otherwise dark compositions to create dramatic effect. Most of these earlier works were Christian subjects, and the light sources were often simple candles. Wright flips the script with his scientific subject matter. The gas lamp which acts as the sun pulls double duty in the painting. It illuminates the scene, allowing the viewer to clearly see the figures within, and it symbolizes the active enlightenment in which those figures are participating.

Additional resources:

“Restoration of Joseph Wright of Derby paintings reveals hidden details” in The Guardian

Biography of Joseph Wright of Derby from The Getty Museum

Joseph Wright of Derby at The National Gallery, London

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Lady Cockburn and Her Three Eldest Sons

by PIPPA COUCH and RACHEL ROPEIK

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Sir Joshua Reynolds, Lady Cockburn and Her Three Eldest Sons, 1773, oil on canvas, 55-3/4 x 44-1/2″ / 141.5 x 113 cm (National Gallery, London)