13.6.12: Gothic

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 88717

Gothic art

The Gothic style brought both divine light and soaring height to medieval churches.

c. 1200 - 1400

A beginner's guide

Gothic architecture, an introduction

Forget the association of the word “Gothic” to dark, haunted houses, Wuthering Heights, or ghostly pale people wearing black nail polish and ripped fishnets. The original Gothic style was actually developed to bring sunshine into people’s lives, and especially into their churches. To get past the accrued definitions of the centuries, it’s best to go back to the very start of the word Gothic, and to the style that bears the name.

The Goths were a so-called barbaric tribe who held power in various regions of Europe, between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire (so, from roughly the fifth to the eighth century). They were not renowned for great achievements in architecture. As with many art historical terms, “Gothic” came to be applied to a certain architectural style after the fact.

The style represented giant steps away from the previous, relatively basic building systems that had prevailed. The Gothic grew out of the Romanesque architectural style, when both prosperity and relative peace allowed for several centuries of cultural development and great building schemes. From roughly 1000 to 1400, several significant cathedrals and churches were built, particularly in Britain and France, offering architects and masons a chance to work out ever more complex and daring designs.

The most fundamental element of the Gothic style of architecture is the pointed arch, which was likely borrowed from Islamic architecture that would have been seen in Spain at this time. The pointed arch relieved some of the thrust, and therefore, the stress on other structural elements. It then became possible to reduce the size of the columns or piers that supported the arch.

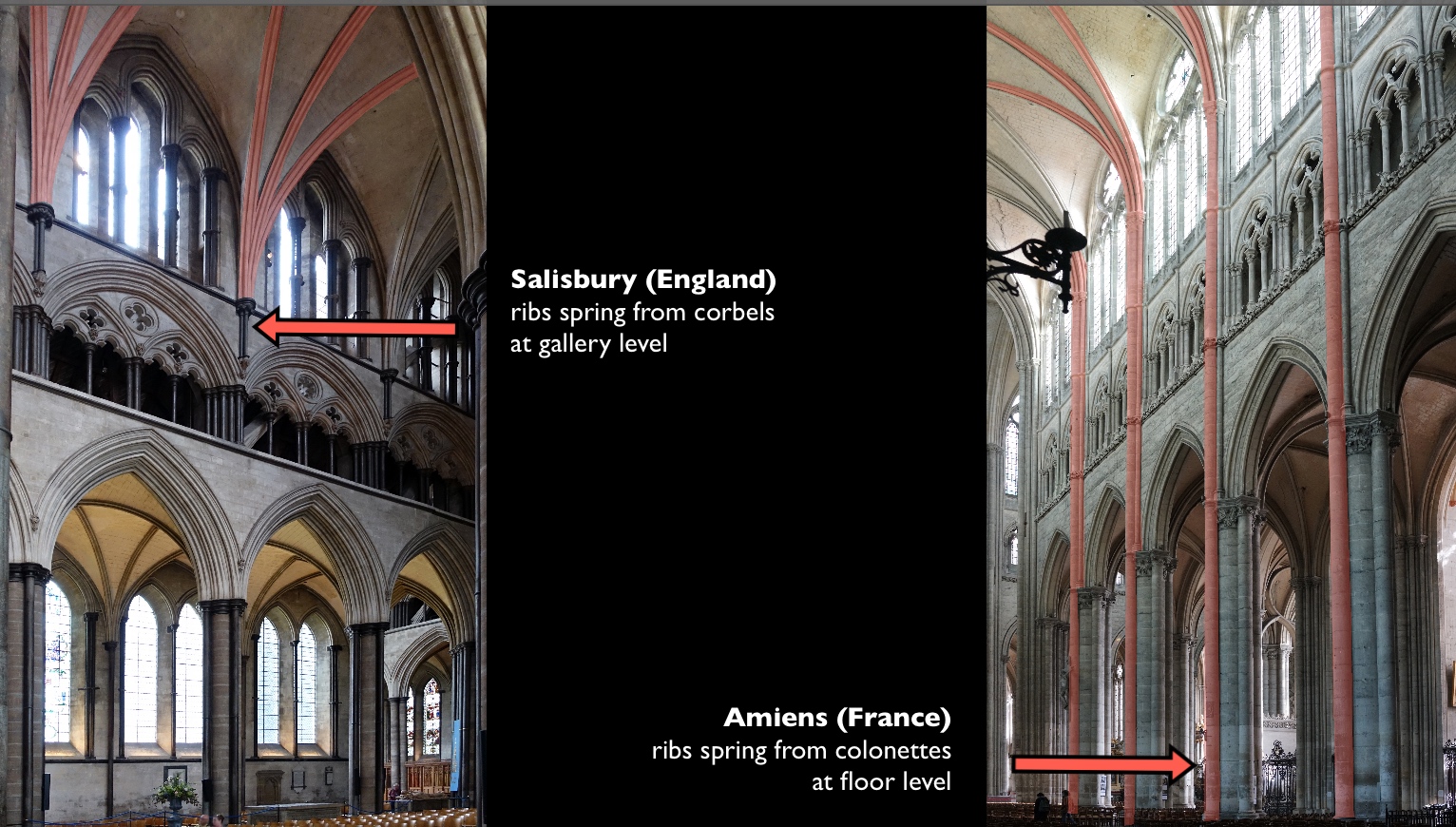

So, rather than having massive, drum-like columns as in the Romanesque churches, the new columns could be more slender. This slimness was repeated in the upper levels of the nave, so that the gallery and clerestory would not seem to overpower the lower arcade. In fact, the column basically continued all the way to the roof, and became part of the vault.

In the vault, the pointed arch could be seen in three dimensions where the ribbed vaulting met in the center of the ceiling of each bay. This ribbed vaulting is another distinguishing feature of Gothic architecture. However, it should be noted that prototypes for the pointed arches and ribbed vaulting were seen first in late-Romanesque buildings.

The new understanding of architecture and design led to more fantastic examples of vaulting and ornamentation, and the Early Gothic or Lancet style (from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries) developed into the Decorated or Rayonnant Gothic (roughly fourteenth century). The ornate stonework that held the windows–called tracery–became more florid, and other stonework even more exuberant.

The ribbed vaulting became more complicated and was crossed with lierne ribs into complex webs, or the addition of cross ribs, called tierceron. As the decoration developed further, the Perpendicular or International Gothic took over (fifteenth century). Fan vaulting decorated half-conoid shapes extending from the tops of the columnar ribs.

The slender columns and lighter systems of thrust allowed for larger windows and more light. The windows, tracery, carvings, and ribs make up a dizzying display of decoration that one encounters in a Gothic church. In late Gothic buildings, almost every surface is decorated. Although such a building as a whole is ordered and coherent, the profusion of shapes and patterns can make a sense of order difficult to discern at first glance.

After the great flowering of Gothic style, tastes again shifted back to the neat, straight lines and rational geometry of the Classical era. It was in the Renaissance that the name Gothic came to be applied to this medieval style that seemed vulgar to Renaissance sensibilities. It is still the term we use today, though hopefully without the implied insult, which negates the amazing leaps of imagination and engineering that were required to build such edifices.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Gothic art in France

The walls opened up and light poured in...

c. 1200 - 1400

Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and the ambulatory at St. Denis

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Ambulatory, Basilica of St. Denis, Paris, 1140-44

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

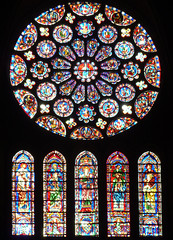

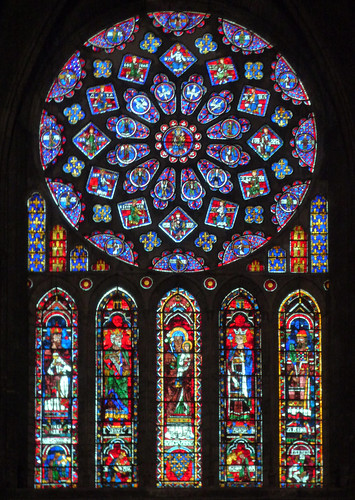

Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres, c.1145 and 1194-c.1220, Chartres (France)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\)

The fire

The blaze that engulfed the Cathedral of Notre Dame on the small Island known as the Île de la Cité in Paris in April 2019 was a terrible tragedy. Though it may not give us much comfort to learn that the total or partial destruction of churches by fire was a fairly common occurrence in medieval Europe, it does provide some perspective. For example, a fire destroyed most of Chartres Cathedral in 1020 (and again in 1194), in the city of Reims, the cathedral was badly damaged in a fire in 1210, and at Beauvais, the cathedral was rebuilt after a fire in the 1180s. The list goes on and on.

During the medieval periods of the Romanesque and the Gothic (c. 1000-1400), church fires were less frequent than they had been previously due to the development of stone vaulting (which began to replace the timber ceilings commonly found in European churches). But even a stone vault, as we saw at Notre Dame in Paris, is itself protected by a timber roof (sometimes rising more than 50 feet above the stone vaulting and pitched to prevent the accumulation of rain and snow), and this is what caught fire.

Art historian Caroline Brazelius, who has worked on the building for years said, “between the vaults and the roof, there is a forest of timber” — old, dry, porous, and highly flammable timber. Still, photographs of the interior show at least some of the stone vaulting survived the recent fire. The builders of Notre Dame used Parisian limestone, but, as Brazelius notes “when it’s exposed to fire, stone is damaged. It doesn’t actually burn….It becomes friable. It chips, and it’s no longer structurally sound.”

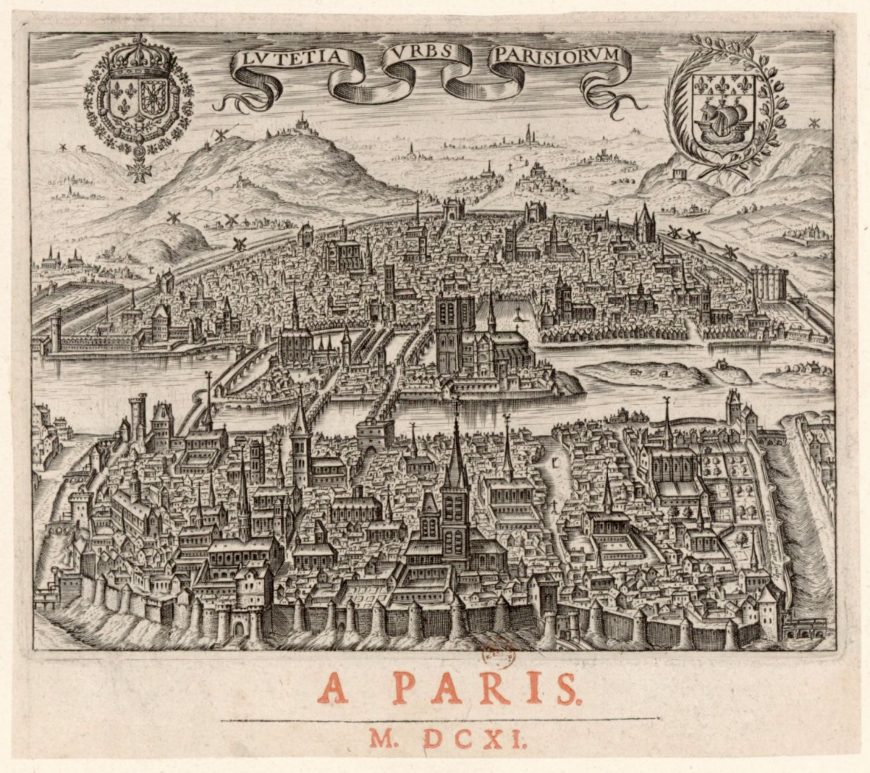

Built, modified, rebuilt, and restored

Churches are often an amalgamation of architectural styles, the result of building campaigns and modifications undertaken at different times, some due to fire, some due to the desire for what a new style represents, and some due to (often inaccurate) restoration efforts. And on a single site, churches were often built and rebuilt—and this is the case with Notre Dame in Paris. Before the Gothic-style church was built, a Carolingian church occupied the site (it was destroyed during the 9th century Viking invasions), and before that, a 6th century Merovingian Church stood on the site.

If we go back further, to the pre-Christian era, Julius Caesar’s armies famously conquered much of what we call France today (Roman Paris dates back to 52 B.C.E.). Archaeological evidence suggests that a pagan temple and then a Christian basilica were built on this site. The ancient Romans also built a palace for the emperor on the Île de la Cité, and after the Roman empire collapsed, Clovis I, King of the Franks (who converted to Christianity) established his palace there as well. The Île de la Cité would remain the location of a royal residence until the 14th century. As one historian has noted, “Notre Dame…was not only a religious but also a royal monument that displayed the might of the church and the monarchy, each enhancing the power of the other.” [1]

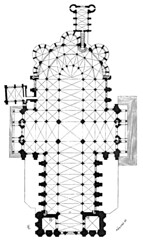

The Gothic Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris took nearly 100 years to complete (c. 1163-1250) and modifications, restorations, and renovations continued for centuries after. The early Gothic style employed at the beginning of the campaign became outdated and the later Gothic style, the Rayonnant, became fashionable and can be seen in the transepts. The crossing spire that the world watched fall while engulfed in flames was a reproduction created during a 19th-century restoration campaign.

In the following centuries, the church (and its sculptural decoration) survived multiple episodes of intentional destruction: during the Protestant Reformation (due to Protestant objection to religious imagery), and during the revolutions of 1789 and 1830 (because of the church’s close association with the monarchy). It remained in a neglected state until Victor Hugo’s novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) revived popular interest the building.

As of this writing, just a few days after the April 15th blaze, evaluation of the damage caused by the fire is only just beginning, but a reported one billion dollars has been already been raised to support the reconstruction of Notre Dame de Paris.

1. Avner Ben-Amos, “Monuments and Memory in French Nationalism.” History and Memory, vol. 5, no. 2, 1993, pp. 50–81.

Additional resources

The Cathedral’s construction (official website of Notre Dame de Paris)

Avner Ben-Amos, “Monuments and Memory in French Nationalism,” History and Memory, vol. 5, no. 2 (1993), pp. 50–81.

Caroline Bruzelius, “The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 69, no. 4 (1987), pp. 540–569.

Stephen Murray, “Notre-Dame of Paris and the Anticipation of Gothic.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 80, no. 2 (1998), pp. 229–253.

Reims Cathedral

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Reims Cathedral (Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims), begun 1211, Reims, France

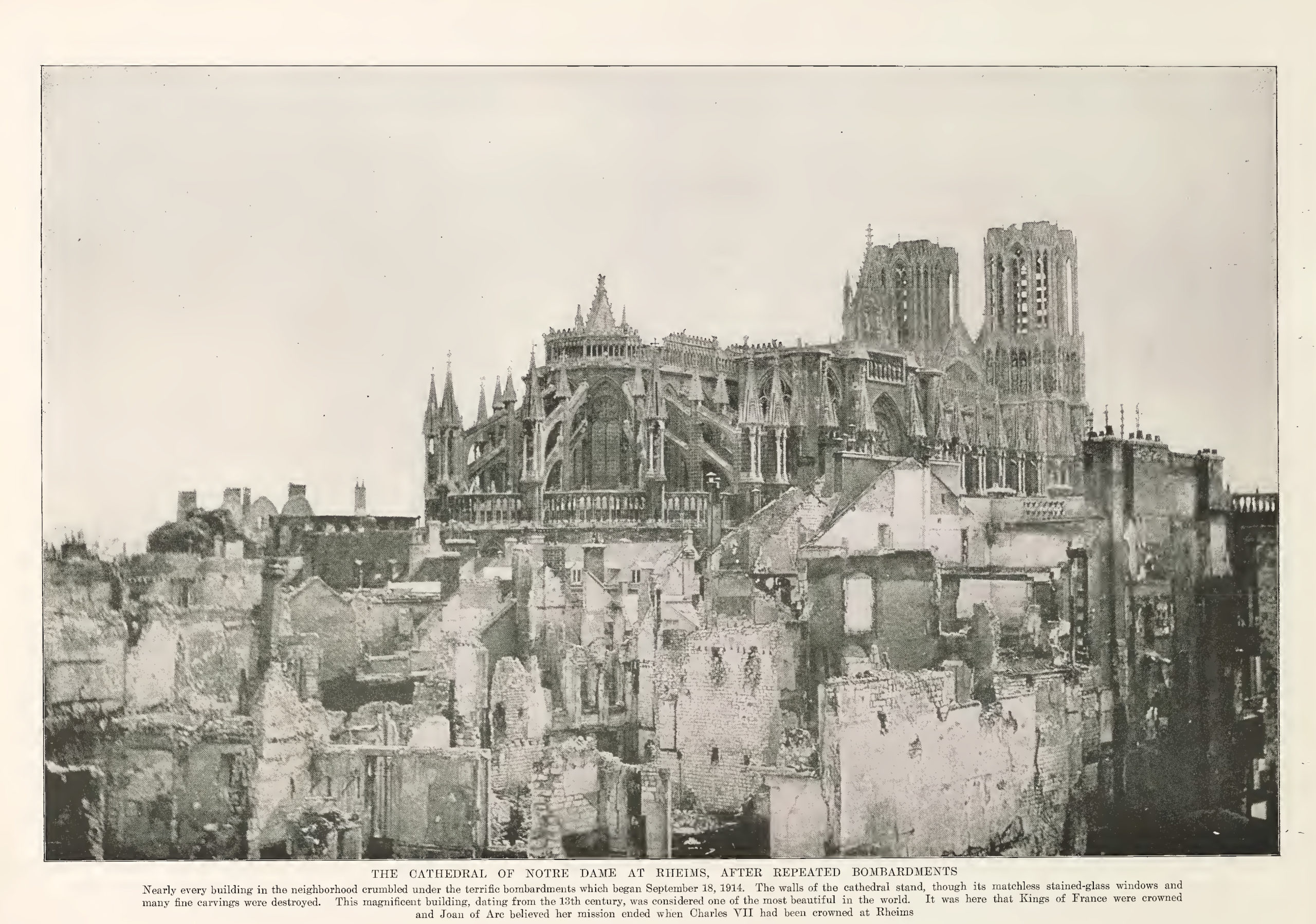

Reims Cathedral and World War I

The facts…?

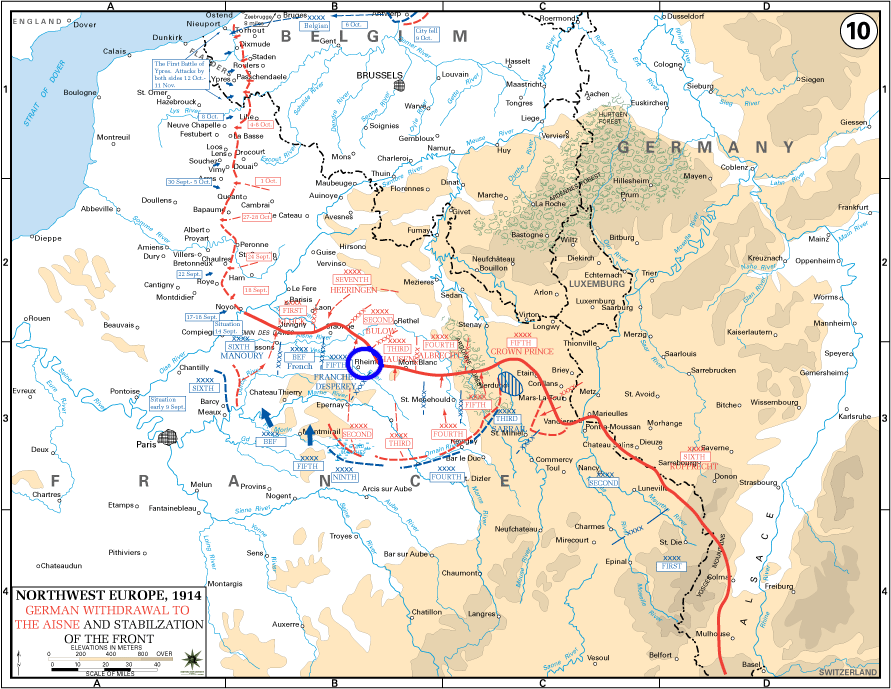

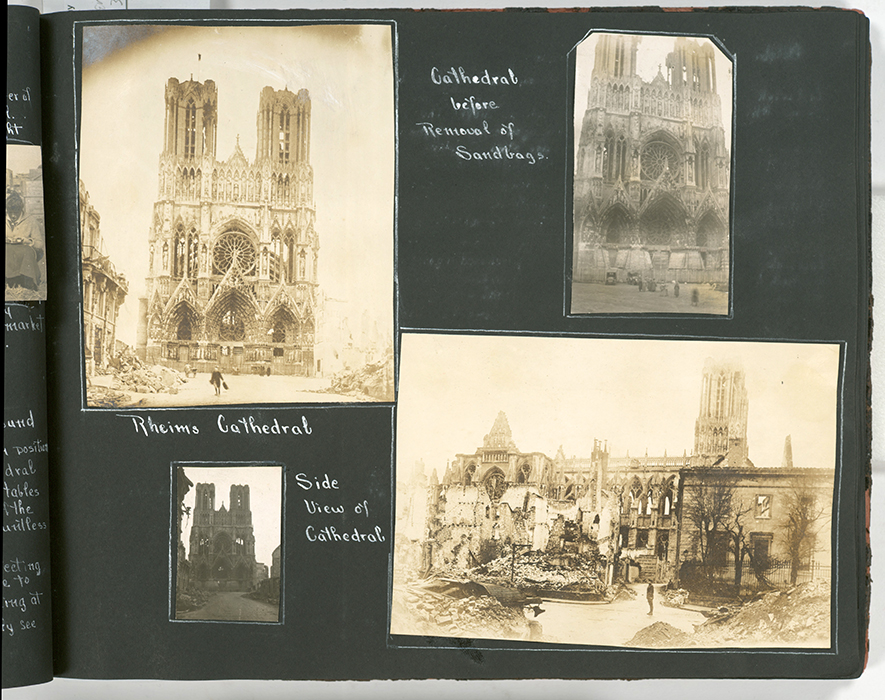

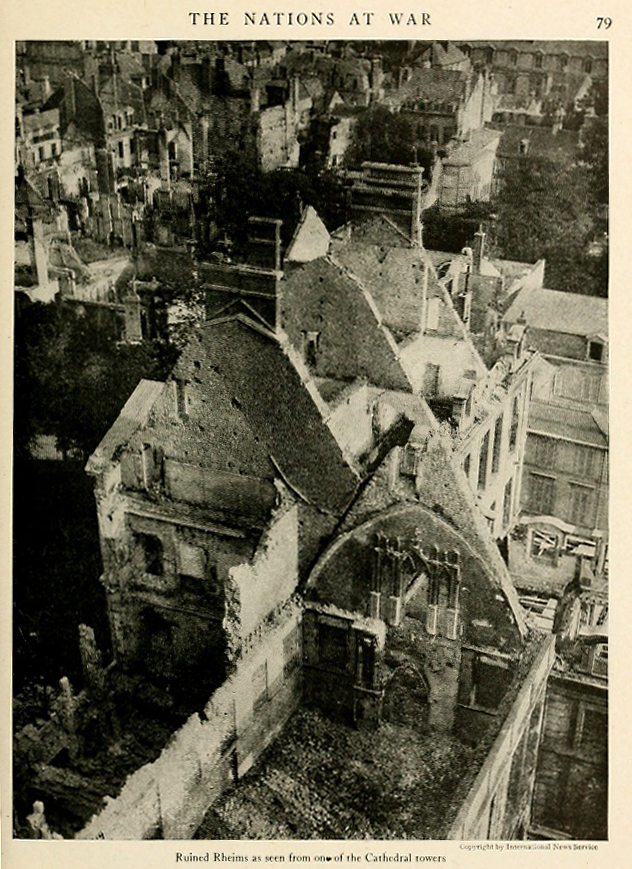

World War I officially started July 28, 1914. Originally it was believed that the “situation” would clear itself up by no later than Christmastime. Instead, it took over four long and grueling years, and resulted in more than 15 million deaths. Early on in the conflict, the German army moved into northeastern French territory. This was the beginning of the Western Front. The expeditious land grab by the Germans included the city of Reims. Reims had a well-established history, from its days as a bustling hub of the Roman Empire, to becoming a center of French culture in the early Middle Ages. Additionally, Reims was the “Coronation Capital,” so to speak, the traditional location for the coronation of French kings. It was also home to a magnificent high Gothic cathedral, Notre-Dame de Reims. By early September, the French had forced the Germans to retreat and though the French regained the town, the Germans stayed close by for the entirety of the war.

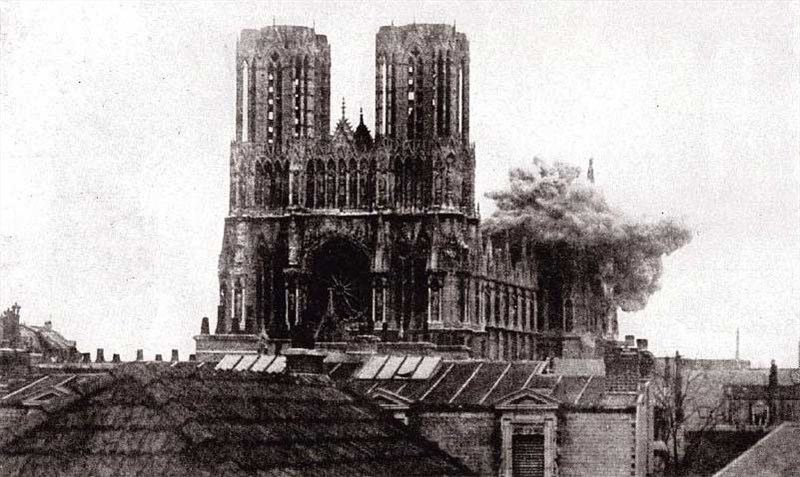

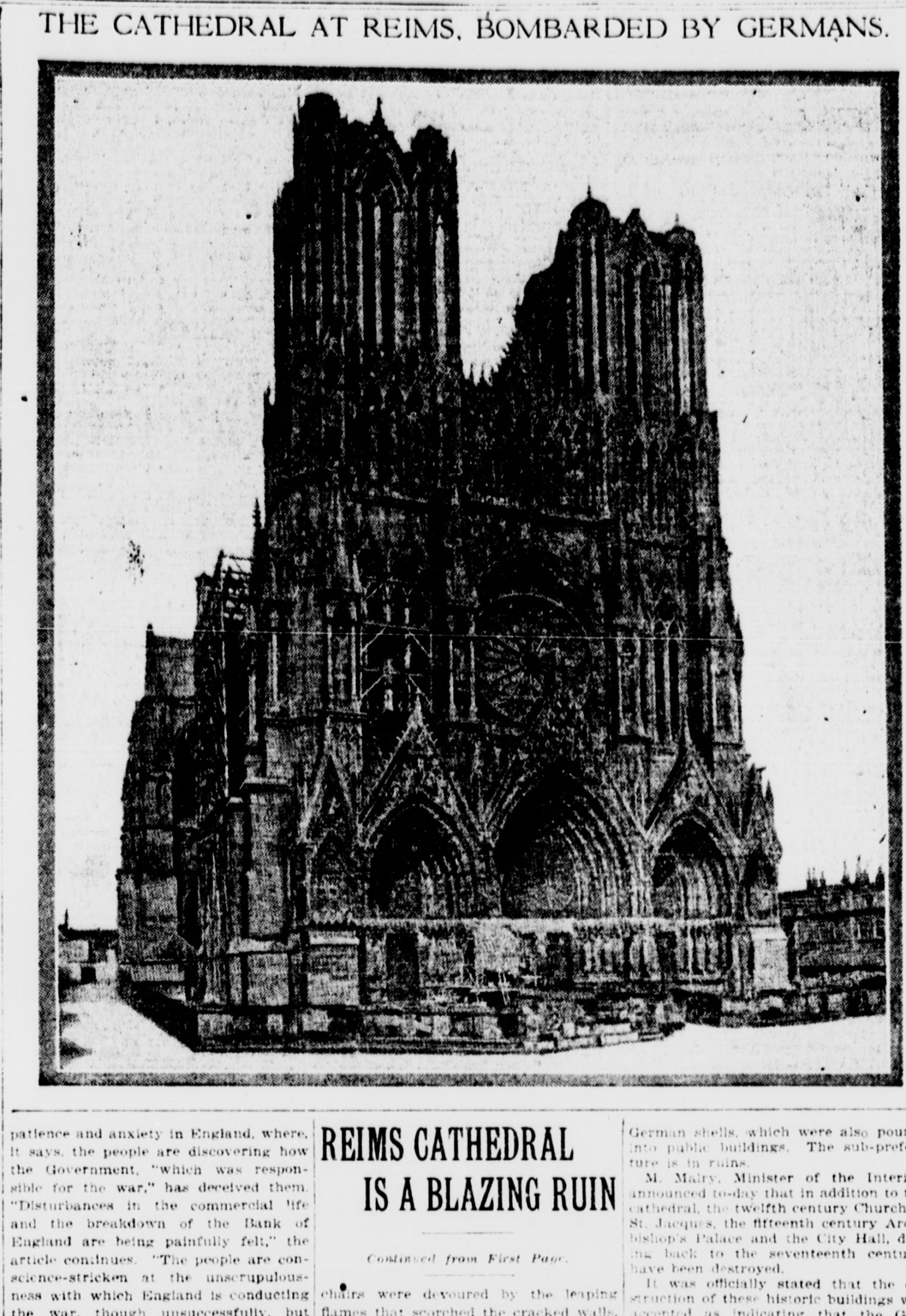

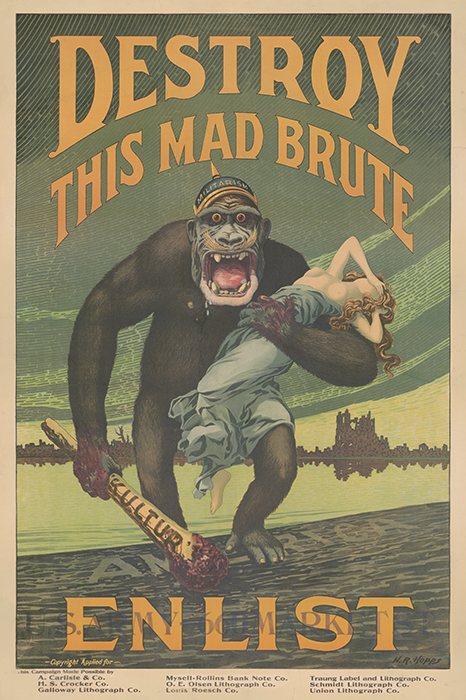

The city of Reims saw significant destruction, and both civilian and military casualties. But no event ignited indignation as did the bombing of the much-venerated Notre-Dame de Reims. The cathedral was first hit by shell fire on September 19th, 1914. Wooden scaffolding that was in place for ongoing repairs caught fire, and contributed to the damage, as did several smaller fires that resulted from the attack. Though the cathedral would be struck again and again as the war continued, it was this initial shelling that sparked a firestorm of outrage, horror, and prodigious propaganda—surely here was damning proof that the Germans were indeed “barbarians,” so lacking in culture themselves that they were compelled to destroy the beauty of another culture out of sheer spite and jealousy. The propaganda insisted that there was no reason to bomb the church since it had no strategic military value, and was a place of sanctuary. The French and their allies stressed that there was no justification to shell the cathedral especially given that was being used to house the wounded (mainly German soldiers callously left behind by their fleeing brothers-in-arms).

War crimes

It was acknowledged, even at the time, that the Germans were committing more horrendous acts than the bombardment of Reims Cathedral. So why should a building create more outcry and indignation than the killing of innocent civilians, or other kinds of wartime savagery? Perhaps it was in part that the cathedral, literally meaning the seat of the bishop, could be seen as representing the French nation as a whole, its cruciform shape evoking a sacrificial body. Or, on a more practical note, it was a story that could be easily sensationalized and discussed ad infinitum—cultural war damage was far easier to get past the censors. In the words of Maurice Landrieux, a former priest at Reims but later the Bishop of Dijon “…but it was the most ignoble, because it was at once sacrilegious and stupid, and because it reveals, by its uselessness, the blackest depth of German misdoing.” There was a pervasive belief that the Germans had come to France with the express intention of destroying the cathedral from the outset of the war.

There are two sides to every story, and so it is here. The Germans did shell the cathedral—that is irrefutable. Their explanation as to why they did so was wildly at odds with the French account, and they claimed to be horrified just as deeply as the French, at the damage done to this architectural masterpiece.

The French story was that is that the Germans, before their hasty retreat, had covered the floors of the cathedral with straw, to make it more combustible and that they intentionally left their wounded knowing they would be brought into the church by the French to be tended. A Red Cross flag was raised, a further signal that the cathedral was off-limits as a military target. However, the Germans later claimed the cathedral was being used for military intelligence: a signal station, telephone equipment, and an observation post had been espied in one of the towers during a German fly-by—along with a large cache of weapons. If true, according to international law, the cathedral was a viable military target—a wolf wrapped in sheep’s clothing.

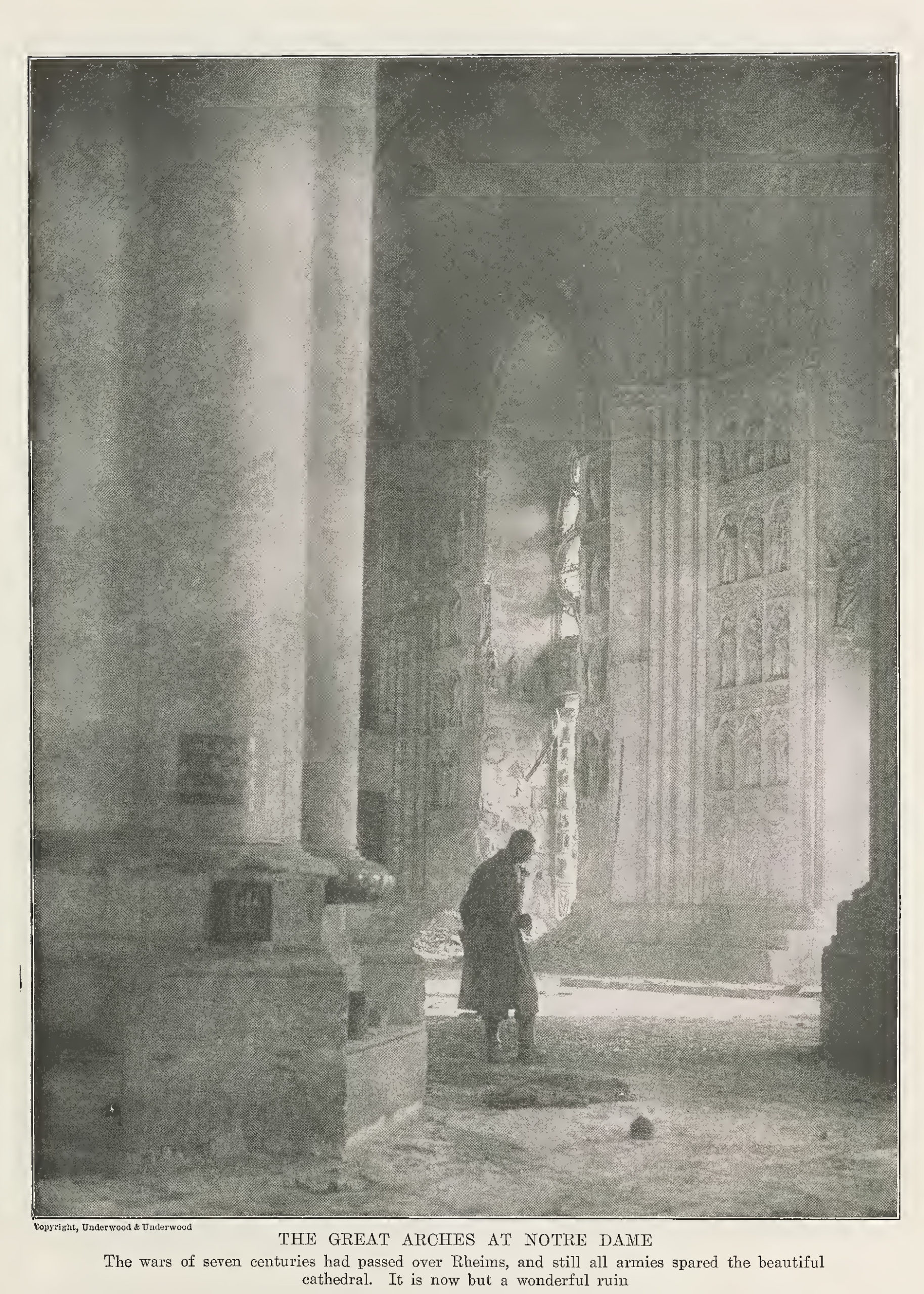

The church was severely damaged—roofs had burned, statues melted, stonework was no longer viable, and more. Nonetheless, the structure was still essentially in good condition after the attack, all things considered. The local French authorities were actually taken to task by their own administrators for not doing a better job putting out the fire, which caused the majority of the damage. The Germans claimed it pained them to commit such an act, but the cunning French had left them no choice. These claims gained little traction.

The result was that—for the French—the German reputation for philosophical thought and general erudition, were suddenly erased—they were viewed once again as one of the “barbarian hordes” of the migration era. German art historians were quick to point out they had been one of the primogenitors of that discipline, and they highly appreciated art from around the globe. German art historians and professors were even dispatched to the front, joining various army units to help provide protection to valuable art on both sides, but to no avail. The mud would not unstick.

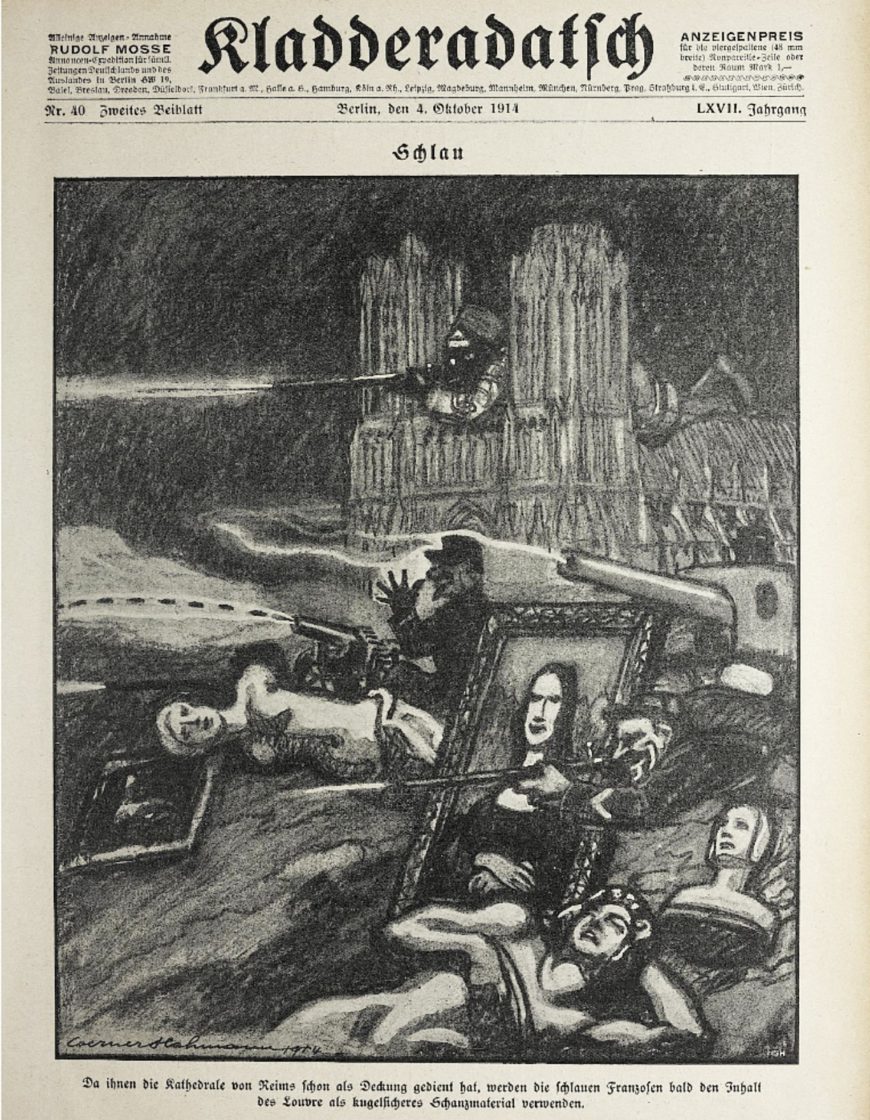

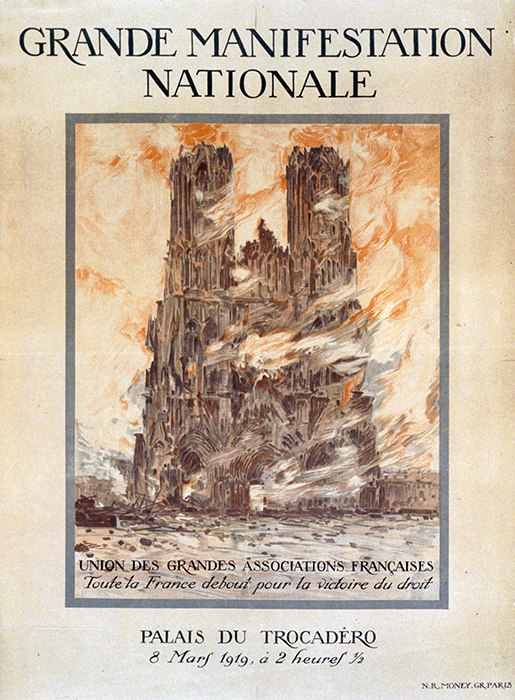

Culture wars

Reims Cathedral continued to be used as propaganda for the whole of the war. Its burnt image was printed on posters and postcards. German soldiers were depicted gun-wielding and slavering at the jaw to seeking to destroy the next great work of art they saw. Meanwhile, the Germans lampooned the French, accusing them of using their own great works of art for nefarious ends without compunction. One well-known cartoon read, “The cunning French have used Reims cathedral as a shooting platform—next they’ll be building trenches with the contents of the Louvre.”

Beyond the trenches, the battle for cultural superiority was on. The French had the upper hand when it came to the events at Reims that fateful night. They could claim eyewitnesses, and they also photographed the cathedral in ways intended to most incite a viewer.

The Germans did try hard though, despite their lack of handy visual evidence, to underscore that they had been the only country to carry out any form of art protection. Kunstschutz (the German term for the principle of preserving cultural heritage and artworks during armed conflict) was said to protect art on both sides of the war. It was even said to be endorsed by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself. The Germans emphasized that the bombing of the cathedral at Reims had not been part of a systematic effort, instead, it was one of the many sad byproducts of the war.

Neither side held back, each was determined to show that while one was on the side of the angels, the other was ruthlessly attempting to profit by the destruction of art. Meanwhile, the Germans claimed that as they were the creators of the Gothic style, and so the cathedral was just as much part of their cultural heritage as it was France’s, and they again attempted to remind the world of their integral role in the creation of art history. Again, this gained no traction with the French, nor with most nations.

By the end of the war Reims, which had been targeted multiple times, was the ruin the French had claimed after the initial attack. The continued attacks on the cathedral called into doubt the veracity of the Germans’ initial account. After the first bombardment, it was certain that the cathedral was no longer being used for any military purpose—if it ever had been. Again, a cultural landmark of this kind could only become subject to brute force with good reason, so the continued bombing only furthered the French position of German brutality and outright vandalism. J.W. Garner, in his International Law and the World War, states, “Monuments of this stature are not only entitled to respect because of their sanctity but are especially protected because of the Law of Nations” (p. 445).

Restoration on the cathedral began almost immediately after the end of the war, funded in part by the Rockefeller family. The cathedral reopened in 1938, though work continues to this day. Recently, the world looked on aghast when, in April of 2019, the iconic Notre-Dame de Paris burned. Even more recently, the lesser-known Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Nantes, another Gothic jewel, caught on fire. In these cases there appears to be no terrorism involved, only age and human error. Perhaps then, the. most important take-away from the bombing of Reims Cathedral is that blame is, to a degree, irrelevant, at least after the fact. The real lesson is that we must do better at preserving our cultural heritage the world over.

Additional resources:

Amiens Cathedral

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Renaud de Cormont, Amiens Cathedral, Amiens, France, begun 1220

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

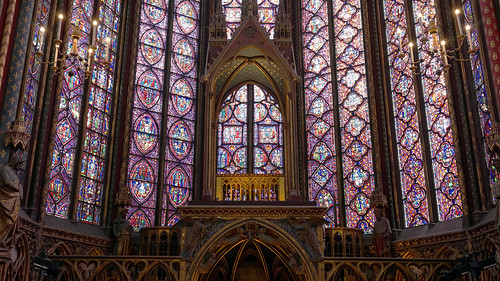

Sainte-Chapelle, Paris

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Sainte-Chapelle, Paris, 1248. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

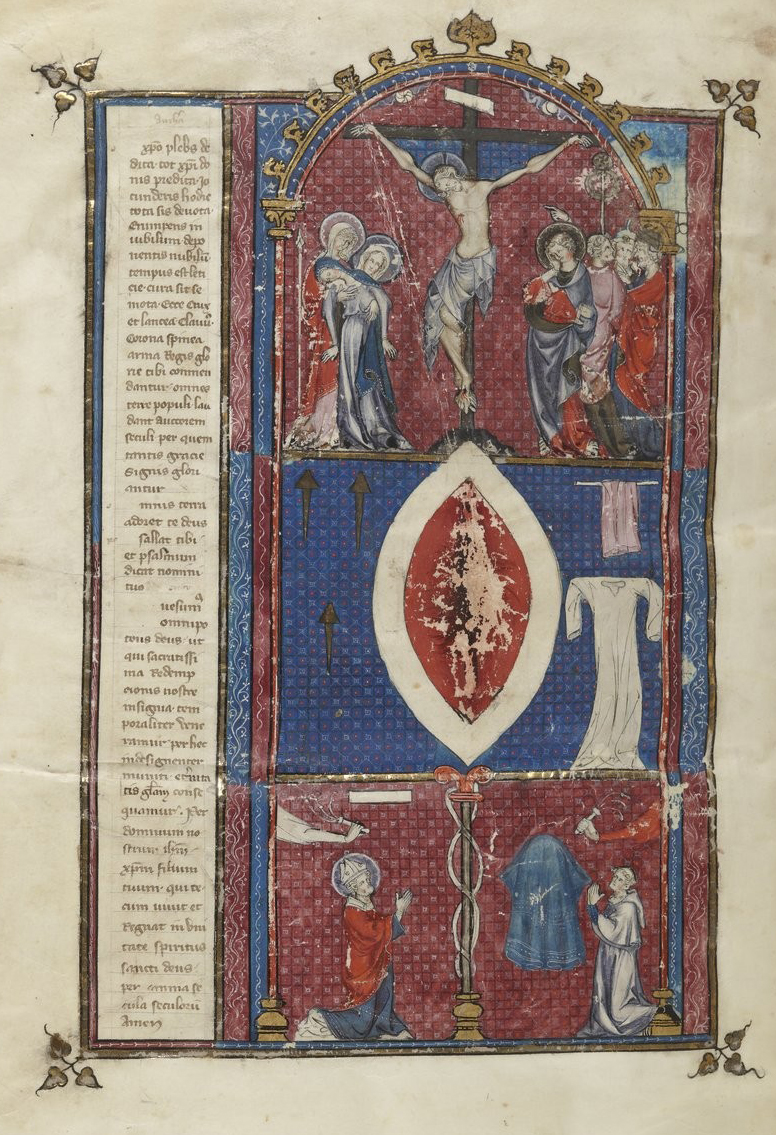

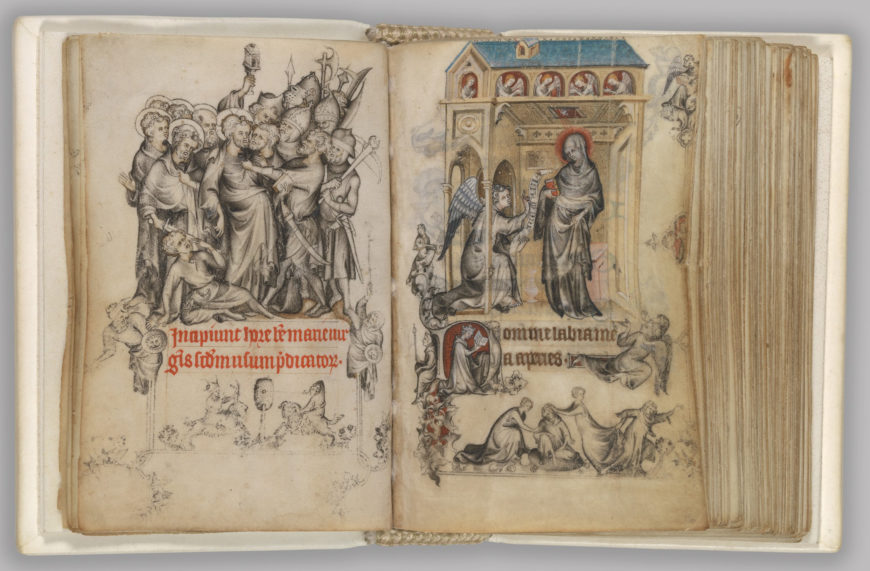

Bible moralisée (moralized bibles)

One book, thousands of illustrations

Imagine a children’s illustrated bible. There might be 2-3 illustrations for each story: Adam and Eve in the garden, Noah’s ark, Daniel in the lion’s den, and others. If you open a regular copy of the bible, each of these stories are covered in several pages of densely-written ancient text. Now imagine that you had a book that contained a separate illustration for every few sentences in the entire bible. Imagine that this super illustrated bible also contained another text that interpreted the bible text and that your book also contained illustrations of that additional text. One book: thousands of illustrations. It is medievally mind-blowing.

The Bible moralisée, or moralized bibles, are a small group of illustrated bibles that were made in thirteenth-century France and Spain. These books are among the most expensive medieval manuscripts ever made because they contain an unusually large number of illustrations. These books were generally commissioned by members of royal families, as no one else would have been able to afford such luxury. Below is a dedication page showing the owners of one Bible moralisée: Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France.

Biblical text and commentary

Bible moralisée contain two texts: the biblical text and the commentary text, which is sometimes called a gloss. These commentary texts interpreted the biblical text for the thirteenth century reader. Commentary authors often created comparisons between people and events in the biblical world and people and events in the medieval world. In the case of the Bible moralisée, the commentary often draws parallels between the bad guys of the biblical text and those who were perceived as bad guys in the thirteenth century. In France, as in most of western Europe at this time, Jews and corrupt priests were the bad guys and there are anti-semitic themes throughout the commentary and illustrations.

The format of Bible moralisée manuscripts is unusual, as the artist had to create a coherent arrangement for the biblical text, its accompanying commentary text, and an illustration for each. On each page of this manuscript there are eight circles, called roundels, that illustrate biblical scenes and commentary scenes. There are short snippets of text, either from the bible or commentary, that accompany each scene.

The example presented here is from the Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, which is broken up into three volumes in three different cities. This page, or folio, is from the Apocalypse, or Book of Revelation. The text tells the story of John’s vision, where an angel takes him on a tour of heaven and shows him everything that will happen until the end of time, but in symbols. The gist of the story is that there is an ongoing battle between God and evil and ultimately God and his angels win.

In looking at the page, it breaks down into a number of parts and it is important to identify each part in order to understand how the texts and images work together. The Latin text in the upper left is from Revelation 14:19, which translates as

“And the angel thrust in his sharp sickle into the earth, and gathered the vineyard of the earth, and cast it into the great press of the wrath of God:”

(Douay-Rheims translation)

The illustration is a visual interpretation of this text, with some extra details added. A figure on the right harvests grapes from the vines on the right and Christ, with his cruciform (cross-shaped) halo, pours the grapes from the basket on his back into the winepress. God and his angels bless the scene from above.

The commentary begins with the red letter “P” below and talks about how the great winepress signifies hell. Note that in the accompanying illustration (very top of this page), there are demons herding the damned into a hellmouth—literally the jaws of hell. Among the damned is a corrupt bishop, identified by his special hat, the mitre. There is also a corrupt king in hell.

This arrangement give the biblical text three interpretations: a visual interpretation, a commentary interpretation, and a visual commentary interpretation. Each interpretation builds on the other. The illustrations are more than simple representations of the text, they are contemporary interpretations of it. The commentary text does not mention bishops or kings, but the illustrator adds those.

The reader then moves on to the right, to the next pairing of images and text.

The upper portion of text comes from Revelation 15:1, which translates as

“And I saw another sign in heaven, great and wonderful: seven angels having the seven last plagues. For in them is filled up the wrath of God.”

(Douay-Rheims translation)

The accompanying illustration shows Christ on the left and seven angels on the right. The commentary beginning with the blue letter “P”, interprets the seven angels as faithful preachers who teach God’s people. The illustration shows priests on the left teaching a group of men (below). The illustrator goes further and adds two Jewish men on the right, identified by their conical hats. The faithful priests are contrasted with the Jewish men who literally turn their bodies away from the priests. Illustrations like this tried to convince Christian readers that although Jews were once God’s people, as outlined in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, that medieval Jews had turned away from that role. This kind of anti-semitic message promoted hate and violence toward Jews in the later Middle Ages.

Additional resources:

Zoomable image of Scenes from the Apocalypse, from the British Library

The Devil is in the Detail: A Thirteenth-Century Bible Moralisée—blog post from the British Library

Digitized Moralized Bible at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Saint Louis Bible (Moralized Bible or Bible moralisée)

by LOUISA WOODVILLE

Blanche of Castile

In 1226 a French king died, leaving his queen to rule his kingdom until their son came of age. The 38-year-old widow, Blanche of Castile, had her work cut out for her. Rebelling barons were eager to win back lands that her husband’s father had seized from them. They rallied troops against her, defamed her character, and even accused her of adultery and murder.

Caught in a perilous web of treachery, insurrections, and open warfare, Blanche persuaded, cajoled, negotiated, and fought would-be enemies after her husband, King Louis VIII, died of dysentery after only a three-year reign. When their son Louis IX took the helm in 1234, he inherited a kingdom that was, for a time anyway, at peace.

A manuscript illumination

A dazzling illumination in New York’s Morgan Library could well depict Blanche of Castile and her son Louis, a beardless youth crowned king. A cleric and a scribe are depicted underneath them (see image at the top of the page). Each figure is set against a ground of burnished gold, seated beneath a trefoil arch. Stylized and colorful buildings dance above their heads, suggesting a sophisticated, urban setting—perhaps Paris, the capital city of the Capetian kingdom (the Capetians were one of the oldest royal families in France) and home to a renowned school of theology.

A moralized Bible

This last page the New York Morgan Library’s manuscript MS M 240 is the last quire (folded page) of a three-volume moralized bible, the majority of which is housed at the Cathedral Treasury in Toledo, Spain. Moralized bibles, made expressedly for the French royal house, include lavishly illustrated abbreviated passages from the Old and New Testaments. Explanatory texts that allude to historical events and tales accompany these literary and visual readings, which—woven together—convey a moral.

Assuming historians are correct in identifying the two rulers, we are looking at the four people intensely involved in the production of this manuscript. As patron and ruler, Queen Blanche of Castile would have financed its production. As ruler-to-be, Louis IX’s job was to take its lessons to heart along with those from the other biblical and ancient texts that his tutors read with him.

King and queen

In the upper register, an enthroned king and queen wear the traditional medieval open crown topped with fleur-de-lys—a stylized iris or lily symbolizing a French monarch’s religious, political, and dynastic right to rule. The blue-eyed queen, left, is veiled in a white widow’s wimple. An ermine-lined blue mantle drapes over her shoulders. Her pink T-shaped tunic spills over a thin blue edge of paint which visually supports these enthroned figures. A slender green column divides the queen’s space from that of her son, King Louis IX, to whom she deliberately gestures across the page, raising her left hand in his direction. Her pose and animated facial expression suggest that she is dedicating this manuscript, with its lessons and morals, to the young king.

Louis IX, wearing an open crown atop his head, returns his mother’s glance. In his right hand he holds a scepter, indicating his kingly status. It is topped by the characteristic fleur-de-lys on which, curiously, a small bird sits. A four-pedaled brooch, dominated by a large square of sapphire blue in the center, secures a pink mantle lined with green that rests on his boyish shoulders.

In his left hand, between his forefinger and thumb, Louis holds a small golden ball or disc. During the mass that followed coronations, French kings and queens would traditionally give the presiding bishop of Reims 13 gold coins (all French kings were crowned in this northern French cathedral town.) This could reference Louis’ 1226 coronation, just three weeks after his father’s death, suggesting a probable date for this bible’s commission. A manuscript this lavish, however, would have taken eight to ten years to complete—perfect timing, because in 1235, the 21-year-old Louis was ready to assume the rule of his Capetian kingdom from his mother.

A link between earth and heaven

Queen Blanche and her son, the young king, echo a gesture and pose that would have been familiar to many Christians: the Virgin Mary and Christ enthroned side-by-side as celestial rulers of heaven, found in the numerous Coronations of the Virgin carved in ivory, wood, and stone. This scene was especially prevalent in tympana, the top sculpted semi-circle over cathedral portals found throughout France. On beholding the Morgan illumination, viewers would have immediately made the connection between this earthly Queen Blanche and her son, anointed by God with the divine right to rule, and that of Mary, Queen of heaven and her son, divine figures who offer salvation.

A cleric and an artist

The illumination’s bottom register depicts a tonsured cleric (churchman with a partly shaved head), left, and an illuminator, right.

The cleric wears a sleeveless cloak appropriate for divine services—this is an educated man—and emphasizes his role as a scholar. He tilts his head forward and points his right forefinger at the artist across from him, as though giving instructions. No clues are given as to this cleric’s religious order, as he probably represents the many Parisian theologians responsible for the manuscript’s visual and literary content—all of whom were undoubtedly told to spare no expense.

On the right, the artist, donning a blue surcoat and wearing a cap, is seated on cushioned bench.

Knife in his left hand and stylus in his right, he looks down at his work: four vertically-stacked circles in a left column, with part of a fifth visible on the right. We know, from the 4887 medallions that precede this illumination, what’s next on this artist’s agenda: he will apply a thin sheet of gold leaf onto the background, and then paint the medallion’s biblical and explanatory scenes in brilliant hues of lapis lazuli, green, red, yellow, grey, orange and sepia.

Advice for a king

Blanche undoubtedly hand-picked the theologians whose job it was to establish this manuscript’s guidelines, select biblical passages, write explanations, hire copyists, and oversee the images that the artists should paint. Art and text, mutually dependent, spelled out advice that its readers, Louis IX and perhaps his siblings, could practice in their enlightened rule. The nobles, church officials, and perhaps even common folk who viewed this page could be reassured that their ruler had been well trained to deal with whatever calamities came his way.

This 13th century illumination, both dazzling and edifying, represents the cutting edge of lavishness in a society that embraced conspicuous consumption. As a pedagogical tool, perhaps it played no small part in helping Louis IX achieve the status of sainthood, awarded by Pope Bonifiace VIII 27 years after the king’s death. This and other images in the bible moralisée explain why Parisian illuminators monopolized manuscript production at this time. Look again at the work. Who else could compete against such a resounding image of character and grace?

Additional resources:

Humanizing Mary: the Virgin of Jeanne d’Evreux

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): The Virgin of Jeanne d’Evreux, 1324-39, gilded silver, basse-taille, enamels on gilded silver, stones, and pearls, 68 cm high (Musée du Louvre)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

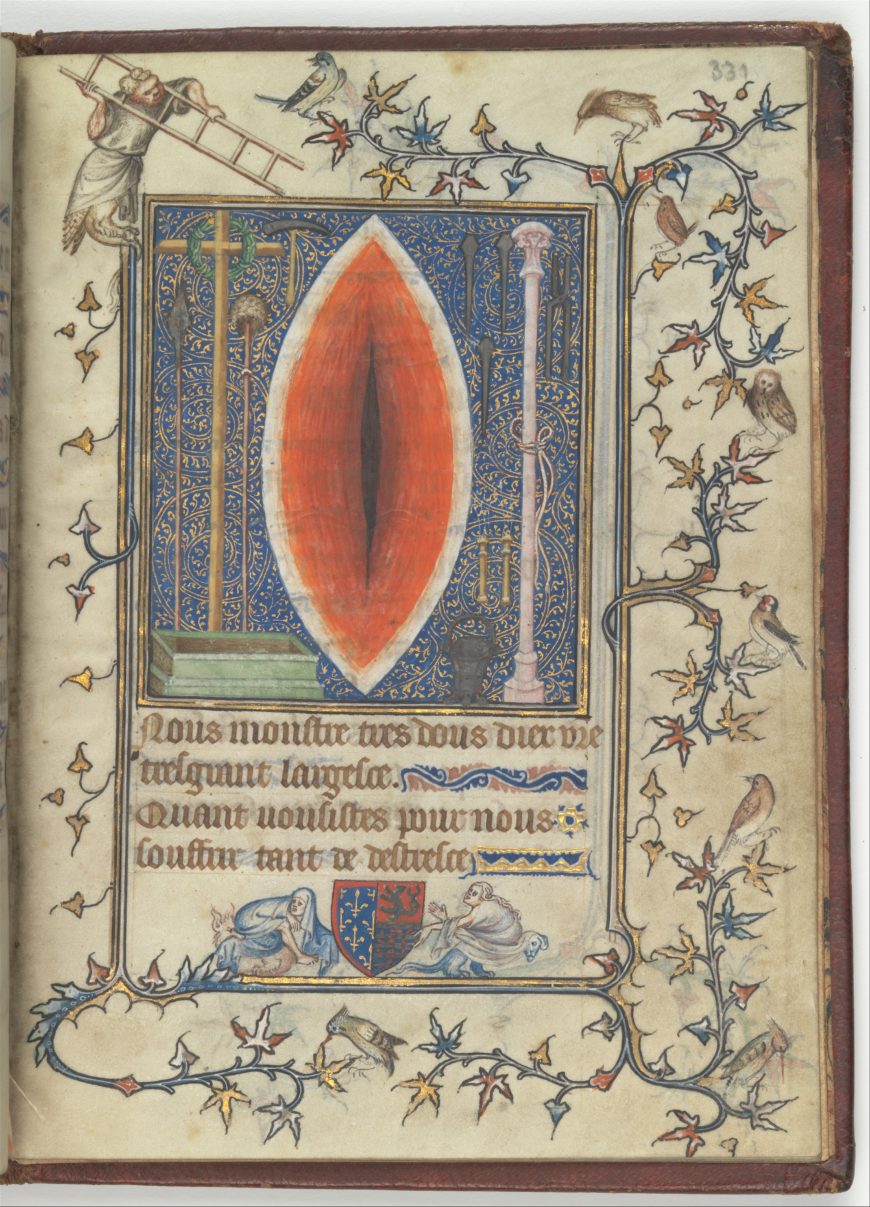

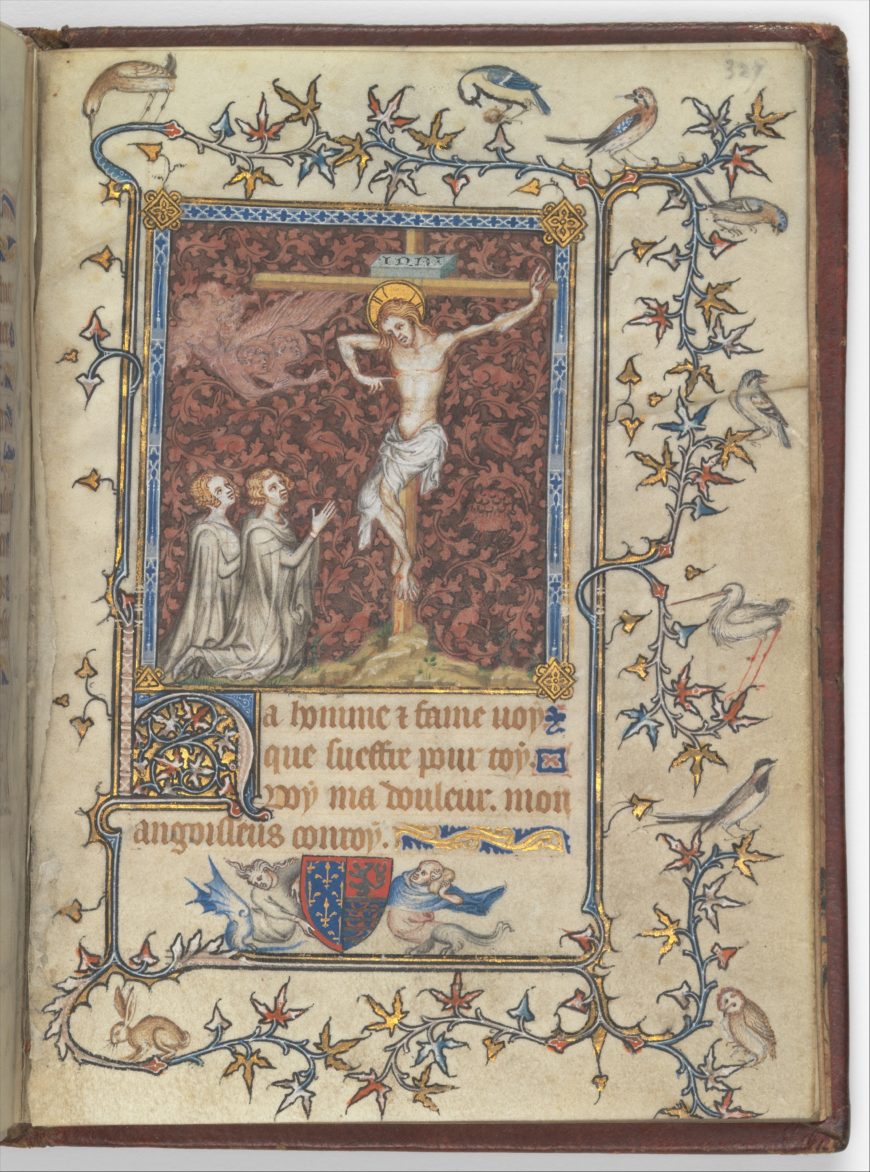

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, Miniature of Christ’s Side Wound and Instruments of the Passion from the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg

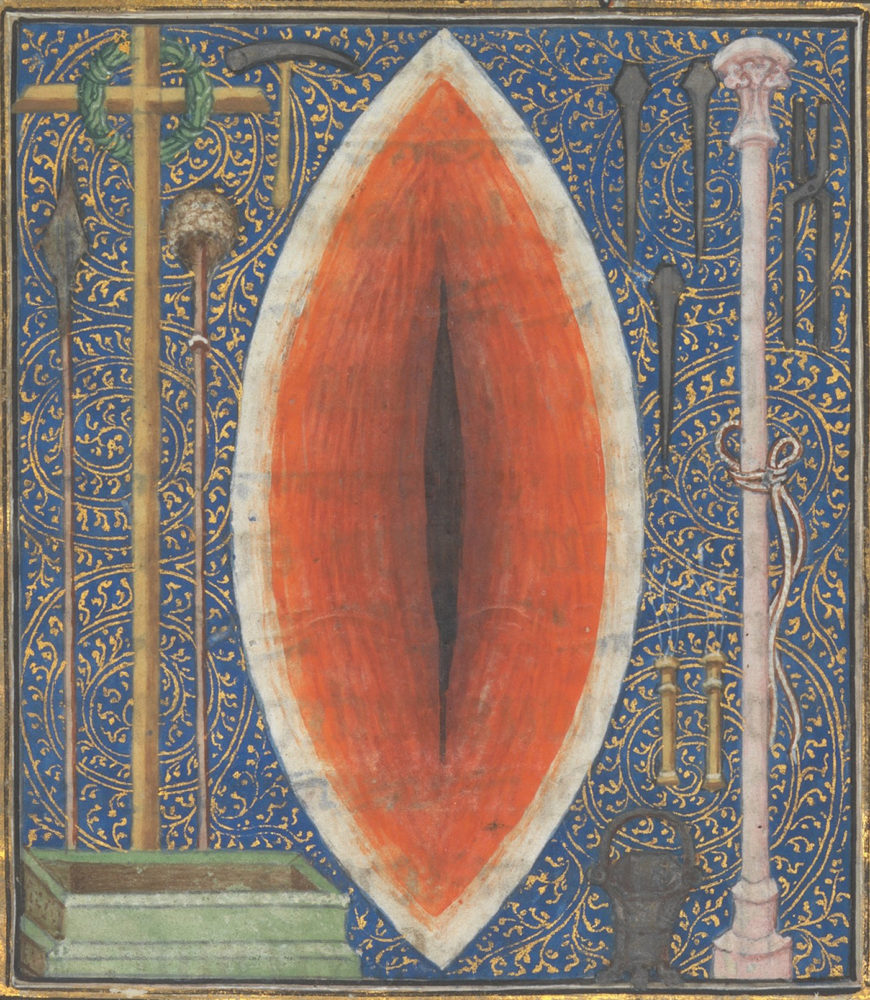

Deluxe medieval devotional books used images and texts together to produce compelling, spiritual experiences for their readers. One particularly dramatic image confronts the reader from the pages of a book made for a woman, Bonne of Luxembourg, in the French royal family. In the center of the parchment page, on a blue field teeming with scrolling golden vines, the instruments used to torture Christ during the Passion stand arranged for the viewer’s inspection.

In the center, filling the composition from top to bottom, is a gaping, disembodied wound. Framed with an almond-shaped ring of white flesh, the bright orange-red tones of torn flesh deepen in color closer to the irregular, vertical brown gash in the center. This is the spear wound created in Christ’s side after his death on the cross, isolated for the pious reader’s contemplation. Shown at what medieval Christians believed to be actual size (about 2 inches), the wound dominates the composition while the miniature instruments of torture that surround it seem to fade into the background. Along with the text (a prayer describing Christ’s suffering), and the manuscript’s lively margins, this graphic painting worked to engage viewers in emotional contemplation of Jesus’ sacrifice.

In the Middle Ages, this powerful image was meant to orient pious readers’ attention to Christ’s body and the physical suffering he endured to ensure their salvation. This emphasis on Christ’s body is part of a larger trend in late medieval devotion known as affective piety, in which compassion for Christ’s suffering held the key to salvation. With its almond shape, vertical orientation, and confrontational placement, the wound of Christ in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg might remind a modern viewer of the Eye of Sauron (known from J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings). Medieval viewers likely overlaid other associations onto such images of Christ’s wound. The change in the wound’s orientation from a diagonal slit to a vertical opening and the isolation of the wound as an almond-shaped device transform it into an image strongly reminiscent of medieval representations of the vulva and the vaginal opening. Similar imagery persists in modern visual culture, such as Judy Chicago’s 1979 installation The Dinner Party. This association of Christ’s side wound with female reproductive organs has connections with mystical writings that eroticized the body of Christ and that emphasized its nurturing and generative qualities.

The Manuscript Context

Although we often think of paintings today as freestanding, portable objects, paintings in medieval books were not meant to be isolated from their manuscript context. When closed, Bonne’s prayer book measures just over five inches high—smaller than an adult’s hand. This small size distinguishes personal prayer books from books sized for display, like the Winchester Bible. Deluxe prayer books like Bonne’s were status symbols, but they were also intimate, personal objects that facilitated direct communication with God.

The image of Christ’s side wound is one of fifteen miniatures distributed among the 334 folios of the prayer book. Each miniature introduces and illustrates the themes of the manuscript’s most important texts. The miniature of the wound comes in the midst of the final text, focusing on Christ’s experience on the cross.

This text opens with a miniature of the crucified Christ showing his side wound to two kneeling figures: Bonne and her husband, the future French king John the Good. Viewed in sequence, the miniature with the crucified Christ instructed Bonne (personally!) where to focus her devotional attentions, while the miniature of the wound three folios later provided her direct, visual access to it. The wound provides a dramatic climax to the prayer and the book.

Mysticism and Queer Readings

Devotion to Christ’s side wound emerges from late medieval Christian mysticism, writings by monastic men and especially women articulating their personal, visionary, and ecstatic experiences of the divine. In mystical writings, Christ’s body often takes on feminine qualities, becoming permeable, generative, and nourishing. Catherine of Siena’s biography records a vision in which Christ nourishes the mystic from his side wound, an encounter that is simultaneously maternal and erotic:

With that, he tenderly placed his right hand on her neck, and drew her towards the wound in his side. ‘Drink, daughter, from my side,’ he said, ‘and by that draught your soul shall become enraptured with such delight that your very body, which for my sake you have denied, shall be inundated with its overflowing goodness.’ Drawn close in this way, … she fastened her lips upon that sacred wound, … and there she slaked her thirst.[1]

Images of the side wound and the mystical tradition from which they emerge have provided fertile material for scholars engaged in “queering” the Middle Ages. Queering means questioning assumptions of heterosexual and cisgender normativity in the past, providing a critique of modern scholarship in the process.

The image of the side wound, like Catherine’s vision, grants feminine bodily attributes to Christ, destabilizing assumptions about his gender. In mystical images and texts, Christ’s capacity to transcend the gender binary, like his capacity to transcend the binary of life and death, underscores his divinity. Christ is not the only figure within medieval culture to transgress the gender binary. Medieval literature—religious and secular alike—is replete with transgender figures, from saints like Marinos the Monk and, perhaps, Joan of Arc, to the fictional protagonists of the thirteenth-century romances Silence and Yde et Olive.

While the voices of actual marginalized people are rarely recorded in medieval documents, Eleanor Rykener is a striking exception. Arrested in late fourteenth-century London for sexual misconduct, and named in court records as John, she identified herself as Eleanor in her testimony. While the gender-ambiguous Christ is a social construction, it can nevertheless call our attention to individuals and groups hidden within or excluded from the historical record and give modern students a means to consider their positions and experiences within their time.

Echoing the eroticism of Catherine’s vision, medieval readers’ interactions with their devotional books could be very intimate, including the touching or kissing of images, and other images of the wound of Christ show paint loss from readers’ pious stroking of the paint. Such devotion to Christ’s side wound further destabilizes presumptions of heterosexuality in medieval and much modern thought. With its focus on touch and penetration, the devotion of men and women alike to Christ’s side wound had the capacity for queer connotations. The ragged, parted lips of Christ’s wound carried many meanings for their medieval viewers, from the pleasures of being enveloped in divine love to protections in childbirth.

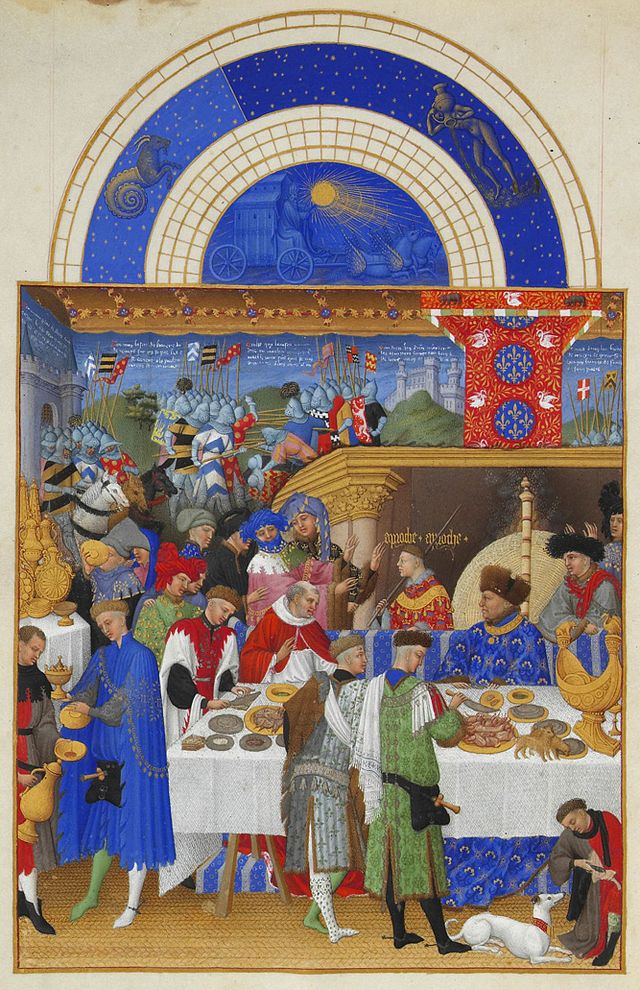

Bonne, who was married at seventeen to the French royal heir and bore nine children before her death of plague at age 34, may have found these associations with pregnancy particularly meaningful. However, the reproductive and the erotic resonances of the image are not mutually exclusive, and, regardless of Bonne’s sexuality, we can see in this imagery a potential model for same-sex desire in the Middle Ages. Such models are crucial for the study of sexualities in a period when homosexual relationships, especially between women, were rarely acknowledged in mainstream texts or conversations. When references to homosexuality do appear in medieval art, it is often framed as a sin, as in the representations of “sodomy” in moralized bibles. Still, more subtle, positive references to homosexual identities may be found. Medieval gossip about Bonne’s son, Jean, Duke of Berry, implies that he may have been attracted to men. Art historian Michael Camille has suggested that Paul de Limbourg devised several well-dressed young men in the feasting miniature of the Très Riches Heures for the duke’s pleasure.

Artists, Patrons, and Owners

The images and texts of Bonne of Luxembourg’s prayer book contained many layered messages for its royal reader. While the content of images and texts alike would have been planned by a devotional adviser, the paintings are attributed to Parisian illuminator Jean le Noir and his workshop, which by 1358 included his daughter, Bourgot, in a prominent role. The commercial book shops of the late Middle Ages were collaborative, often family enterprises, with men and women of different generations working side-by-side. Three artists’ hands have been identified within the manuscript, though it is not possible to know which belonged to Jean, Bourgot, or other workshop members.

Jean le Noir’s workshop specialized in the grisaille style of painting first popularized among the royal patrons of France during the previous generation by illuminator Jean Pucelle. The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg looks back both in style and in content to the miniature prayer book Pucelle made for an earlier queen of France, Jeanne d’Évreux, between about 1324 and 1328.

While the imagery of Bonne’s prayer book brought her into intimate contact with God, its style connected her with the royal French line. These connections were carried forward by Bonne’s children, particularly Jean de Berry, who around 1371 commissioned a prayer book with the same Passion texts as his mother’s from the now elderly Jean le Noir. These stylistic, thematic, and textual traditions across generations speak to the complex dynamics of transgression and normativity within medieval manuscript patronage at the highest levels.

Notes

- Raymond of Capua, The Life of Catherine of Siena, trans. Conleth Kearns, quoted in Karma Lochrie, “Mystical Acts, Queer Tendencies,” in Constructing Medieval Sexuality, ed. Karma Lochrie, Peggy McCracken, and James A. Schultz (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 188.

Additional resources

Read more about Private Devotion in Medieval Christianity on the Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline

Roland Betancourt. “Transgender Lives in the Middle Ages through Art, Literature, and Medicine.” The Getty Iris (blog), March 6, 2019.

Gabrielle Bychowski. “Were There Transgender People in the Middle Ages?” The Public Medievalist (blog), November 1, 2018.

Kadin Henningsen, “‘Calling [herself] Eleanor’: Gender Labor and Becoming a Woman in the Rykener Case” Medieval Feminist Forum 55:1 (2019): 249–266.

Bryan C. Keene and Rheagan Martin. “Coming Out: Queer Erasure and Censorship from the Middle Ages to Modernity.” The Getty Iris (blog), October 11, 2016.

An abstract of Michael Camille’s “‘For Our Devotion and Pleasure’: The Sexual Objects of Jean, Duc de Berry”

Gothic art in England

Crazy vaults, ball flowers, and carved angels that appear to sing...

c. 1200 - 1400

Southwell Minster

Southwell Minster in Nottinghamshire, England, is not as famous as some of Britain’s other great medieval churches, and neither is it as large. However, it presents superb examples of both Romanesque or Norman and Gothic architecture in a building that suffered little damage during the turbulent years of the British Reformation, Civil War, and World War II.

Construction of the current church building was begun circa 1108, and was essentially completed around 50 years later. The basic layout for churches at that time was the shape of a cross, with the east end as the top, the transepts making the crossing arm, and the nave as the longer extension at the bottom of the cross. The east end held the altar and choir, or quire, which were used by the clergy during daily masses. The nave was accessible to the lay community. Although medieval British churches are basically oriented east to west, they all vary slightly. When a new church was to be built, the patron saint was selected and the altar location laid out. On the saint’s day, a line would be surveyed from the position of the rising sun through the altar site and extending in a westerly direction. This was the orientation of the new building.

In clerical terms, Southwell Minster is a cathedral; but rather than rummage in ecclesiastical definitions, this essay will look at the architectural styles.

Interior order

On entering Southwell Minster, the sense of space feels logical and follows a well-defined and rhythmic order. The nave is in the Norman, or Romanesque, architectural style. It is delineated by simple rounded – Roman – stone arches springing from heavy round stone columns. The arcade on each side separates the nave from the side aisles, which allow people to move through the church to smaller side chapels. Above the first tier is a second arcade with smaller arches defining the gallery, and above that is another arcade – smaller still – which includes windows and is known as the clerestory. The ceiling of Southwell Minster is a wooden barrel vault.

The arches, column capitals, window surrounds, and portals are decorated with carved patterns that are geometric and straightforward. Although the material is stone, its lack of detailed texture gives it a plastic quality, especially when seen in some lights. The stone, Permian sandstone, has a warm cream color, while the heavy arches and massive walls impart a feeling of strength and permanence. This commanding style represented effective propaganda for William the Conqueror, who had invaded Britain in 1066 and imposed strong organizational systems in both the Church and government.

From Norman to Gothic

The transepts are also in the Norman style, severe and blunt. But as you move further east and enter the quire, the uncomplicated architecture and decoration gives way to pointed arches and curlicue embellishments. The sense of moving to a different building and place are somewhat confusing at first, until you are fully inside the east end and find yourself enveloped in the Gothic style.

The original east end of Southwell, and of many other medieval cathedrals, was found to be too small once the building was completed, so the old east end was pulled down and replaced with a larger extension in the latest fashion. Although the new east end was built within roughly one hundred years of the original building, architecture had moved on quickly. Now the arches were pointed at the top, and the decoration was more and more ornate. Structurally, new techniques allowed for larger windows than were possible in the Romanesque idiom.

Prebendary seats of stone

The Chapter House, begun circa 1300, is accessible from the north transept, and was the meeting hall of the original prebends (a clergy member drawing a stipend from Anglican church revenues) associated with the minster. Each prebend, who would have held certain responsibilities for his area of the diocese, had a stone seat on the wall of the chapter house. Each seat alcove is topped with decorated trefoil arches and a variety of leaves. The “Leaves of Southwell” have been documented as some of the best medieval stone carvings in England, and represent oak, ivy, hawthorn, grape, hops, and other flora.

Because the Southwell Chapter House is relatively small, it does not require a center column to support the roof as a larger area would. The octagonal room is topped by a vault carried not only on ribs that reach to the center, but also on cross ribs that span between the main ribs. These intermediate ribs are known as tiercerons, and signify a further development into the more complex and decorated vaults that are an integral part of the English Decorated and Perpendicular Gothic styles.

History and presence

As a whole or in its individual parts, Southwell Minster is a brilliant example of medieval architecture in England and its rapid development over 200 years. The building has suffered relatively little damage or major alteration over its thousand-year life. Indeed, part of its appeal is its architectural integrity, as well as the fact that it is a living (i.e., still in use) building.

As the years have passed, new decoration has been added that reflects a functioning parish community – a baptismal font from 1661, stained glass windows from various centuries, a modern sculpture of Christus Rex from the twentieth century. The church is not overrun with tourists, but is still very much a local parish with an active congregation that continues to use the building, ring the bells, and weave the ties of history into twenty-first century life.

Salisbury Cathedral

by VALERIE SPANSWICK, DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

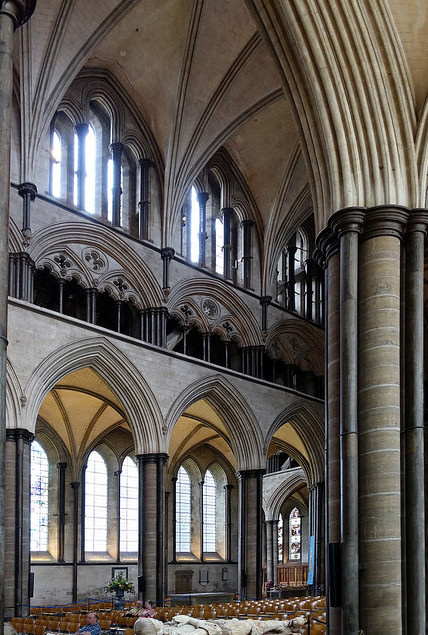

The biggest and the highest

There are so many superlatives consorting with the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Salisbury: it has the tallest spire in Britain (404 feet); it houses the best preserved of the four surviving original copies of the Magna Carta (1215); it has the oldest working clock in Europe (1386); it has the largest cathedral cloisters and cathedral close (grounds) in Britain; the choir (or quire) stalls are the largest and earliest complete set in Britain; the vault is the highest in Britain. Bigger, better, best—and built in a mere 38 years, roughly from 1220 to 1258, which is a pretty short construction schedule for a large stone building made without motorized equipment.

One factor that enabled Salisbury Cathedral to become so extraordinary is that it was the first major cathedral to be built on an unobstructed site. The architect and clerics were able to conceive a design and lay it out exactly as they wanted. Construction was carried out in one campaign, giving the complex a cohesive motif and singular identity. The cloisters were started as a purely decorative feature only five years after the cathedral building was completed, with shapes, patterns, and materials that copy those of the cathedral interior.

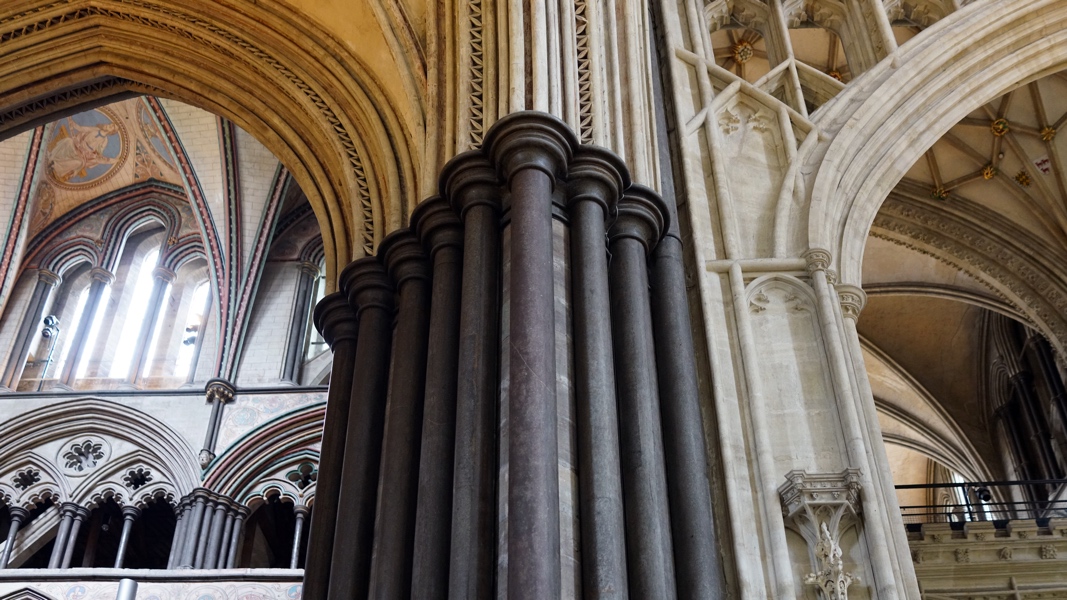

It was an ideal opportunity in the development of Early English Gothic architecture, and Salisbury Cathedral made full use of the new techniques of this emerging style. Pointed arches and lancet shapes are everywhere, from the prominent west windows to the painted arches of the east end. The narrow piers of the cathedral were made of cut stone rather than rubble-filled drums, as in earlier buildings, which changed the method of distributing the structure’s weight and allowed for more light in the interior.

The piers are decorated with slender columns of dark gray Purbeck marble, which reappear in clusters and as stand-alone supports in the arches of the gallery, clerestory, and cloisters. The gallery and cloisters repeat the same patterns of plate tracery—basically stone cut-out shapes—of quatrefoils, cinquefoils, even hexafoils and octofoils. Proportions are uniform throughout.

One deviation from the typical Gothic style is the way the lower arcade level of the nave is cut off by a string course that runs between it and the gallery. In most churches of this period, the columns or piers stretch upwards in one form or another all the way to the ceiling or vault (see diagram below). Here at Salisbury the arcade is merely an arcade, and the effect is more like a layer cake with the upper tiers sitting on top of rather than extending from the lower level.

The tower and the spire

The original design called for a fairly ordinary square crossing tower of modest height. But in the early part of the 14th century, two stories were added to the tower, and then the pointed spire was added in 1330. The spire is the most readily identified feature of the cathedral and is visible for miles. However, the addition of this landmark tower and spire added over 6,000 tons of weight to the supporting structure. Because the building had not been engineered to carry the extra weight, additional buttressing was required internally and externally. The transepts now sport masonry girders, or strainer arches, to support the weight. Not surprisingly, the spire has never been straight and now tilts to the southeast by about 27 inches.

Restorations

Over the centuries the cathedral has been subject to well-intentioned, but heavy-handed restorations by later architects such as James Wyatt and Sir George Gilbert Scott, who tried to conform the building to contemporary tastes. Therefore, the interior has lost some of its original decoration and furnishings, including stained glass and small chapels, and new things have been added. This is pretty typical, though, of a building that is several centuries old. Fortunately, the regularity and clean lines of the cathedral have not been tampered with. It is still refined, polished, and generally easy on the eye.

Sunlight

Although it inspires the usual awe felt in such a grand and substantial building, and is as pretty as a wedding cake, it has had some criticism from art historians: Nikolaus Pevsner and Harry Batsford both disliked the west front, with its encrustation of statues and “variegated pettiness” (Batsford). John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic and writer, found the building “profound and gloomy.” Indeed, in gray weather, the monochromatic scheme of Chilmark stone and Purbeck marble is just gray upon gray.

The pictures, however, show the widely changing character of the neutral tones; sunlight transforms the building, and the visitor’s experience of it. This very quality is what made the Gothic style so revolutionary—the ability to get sunlight into a large building with massive stone walls. Windows are everywhere, and when the light streams through the clerestory arches and the enormous west window, the interior turns from drear gray to transcendent gold.

Additional resources:

The Cathedral of Britain from the BBC

History of Salisbury Cathedral

Salisbury Cathedral Stained Glass

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (Smarthistory essay)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Lincoln Cathedral

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln, begun 1088, Lincoln, England

Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Wells Cathedral

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Wells Cathedral, Wells, England, begun c. 1175. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Four styles of English medieval architecture at Ely Cathedral

Four styles of English medieval architecture

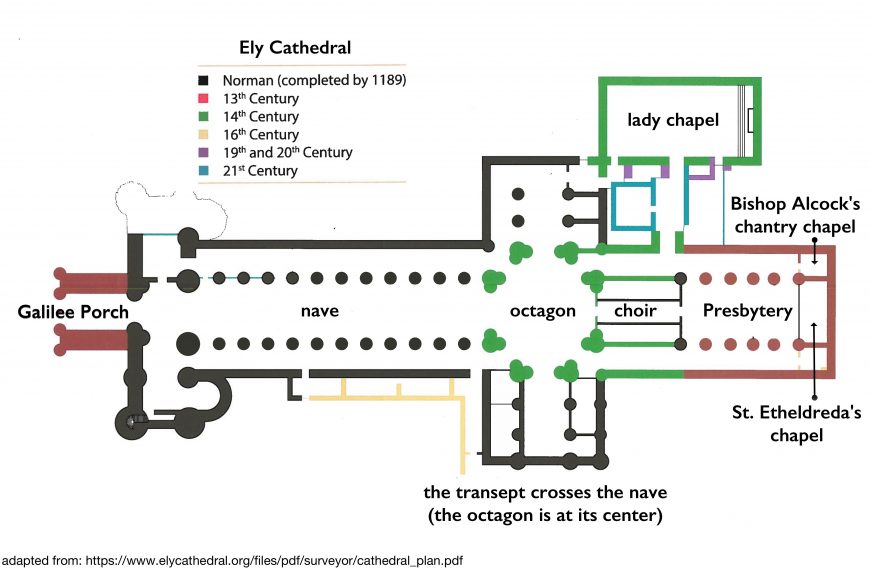

Ely Cathedral, like nearly all medieval English cathedrals, saw many different phases of construction. Major building projects in the Middle Ages were both expensive and time-consuming, so renovations and additions were made piecemeal rather than all at once.The long period of time means that by looking at Ely, we can get a sense of each of the most important medieval English architectural styles, all in one building: Romanesque (in the nave), Early English (in the presbytery), Decorated (in the tower and Lady Chapel), and Perpendicular (in the eastern chantry chapels). See the plan below.

A saint in the marshes

Ely Cathedral, sometimes referred to as “the ship of the Fens,” is a massive building rising up from the flat, marshy fenland of East Anglia. It is visible from many miles away like a lone ship on a calm sea. Ely’s history began in the seventh century, when an Anglo-Saxon princess named Æthelthryth, or Etheldreda, made a holy vow of virginity. When she was married for political reasons, she fled her husband and founded a nunnery on the Isle of Ely. In Etheldreda’s time, Ely was an island surrounded by marshes (drained later, in the seventeenth century), and the place takes its name from the eels that dwelled in these swampy waters.

Etheldreda died just seven years after founding her nunnery. When her body was translated (ceremonially moved), from its original location fourteen years later, it was found to be incorrupt and it was put into a “new” sarcophagus—actually a reused one from an old Roman settlement nearby. A cult developed around Etheldreda, who became a saint (the common name for Etheldreda is St. Audrey).

Etheldreda’s nunnery was raided by Danish invaders in 870. Whether the relics of Etheldreda survived the raid is an open question, but the author of the twelfth-century text, the Liber Eliensis (Book of Ely), detailed stories of the continued power of Etheldreda’s relics, possibly intended to suggest that they had not been destroyed. Relics were very important objects in the Middle Ages, lending prestige to the churches where they were held, and drawing pilgrims, who would come seeking miracles. The existence of Etheldreda’s relics was therefore very important for the identity of the church at Ely, where in 970, with royal patronage, the church was refounded as a Benedictine monastery.

The Romanesque (Norman) building

Though it had been the site of Christian worship for hundreds of years prior to 1082, little is known about the architecture of Ely before this date, when the first Norman abbot of Ely initiated the construction of a new church for the monastery. The foundations were laid out by a man in his 80s named Abbot Simeon who had previously been prior of the important monastic community of Winchester (in the south of England), where his brother, Walchelin, was bishop. Simeon and his brother had orchestrated a building campaign in Winchester that was still underway when Simeon came to Ely, and that in-progress church served as inspiration for much of the Ely building program.

Simeon’s building plans at Ely began in the east end with the choir and transepts. This is typical for churches, since their primary liturgical functions commonly take place in the east end of the church, oriented towards Jerusalem. This part of the church exemplifies the Romanesque style brought from Normandy after the Norman Conquest in 1066. It was completed in two different phases, which we can tell from the new decorative forms that appear on some of the capitals of the columns of the transepts, which were built later than the others.

Work on the nave was begun subsequently, and the south side was completed around 1109, when Ely was officially elevated to the status of a cathedral. Ely’s nave and transepts were some of the first spaces in England to display alternating forms of compound piers. This alternation adds visual rhythm, and diffuses the heaviness of these massive stone forms.

Like most Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals, Ely’s nave elevation has three stories. The nave arcade with its alternating piers is on the ground floor. Above this is a gallery with double-light openings, or double, windowless arches, each pair set within a larger arch that mirrors the corresponding arch on the lower level. The third level is a clerestory with triplet openings. The tremendous thickness of the walls (a distinguishing feature of the Romanesque) is balanced by the proliferation of openings as one’s eyes travel upward. The viewer gets the sense that the building becomes lighter and brighter as it soars heavenward.

Late Romanesque and Early English Gothic

The west tower that tops the cathedral’s main entrance was built at the end of the twelfth century, towards the end of the Romanesque period in England.

Experiments in the Gothic style brought over from France had already begun to take hold in England—particularly at Canterbury Cathedral and the northern Cistercian monasteries. At Ely, though, the tower still exhibits round Romanesque arches instead of the pointed arches that are a hallmark of Gothic architecture.

The exterior is covered almost completely in blind arcading, an English speciality that stands in stark contrast to French medieval architecture, which prefers little extra surface decoration. Below the tower, we see a monumental entrance with blind pointed arches, which was added a bit later in the Early English Gothic style, showing how this new style was rapidly spreading across England during this time.

At the other end of the building, the presbytery was extended eastward in the 1230s and 1240s. In style, it draws from the nave of Lincoln Cathedral, completed just a decade or so earlier. With engaged colonnettes of Purbeck marble and white limestone, as well as complex rib vaults, it reflected the most fashionable architecture of the time. Then, as now, architectural styles came and went quickly, and the wealthiest and most powerful—such as the Bishop and diplomat Hugh of Northwold, who financed the new presbytery—had the means to stay current.

Eastern extensions were popular at this time to provide more room for the shrines of saints, like Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral, or, at Ely, the shrine of Etheldreda. The presbytery was large enough to accommodate the many pilgrims who came to Ely to venerate the saint (and brought important income to the church and surrounding area). Having a highly-decorated space made this holy destination even more desirable.

Ely Cathedral in the Decorated Style

In 1321, a new chapel was begun north of the presbytery, which would eventually become one of the most beautiful and artistically innovative of the English Gothic period. But in the early morning hours of February 13, 1322, just as the monks were finishing their morning prayers, disaster struck. The crossing tower of the cathedral collapsed, crushing parts of the choir, and construction on the chapel had to stop.

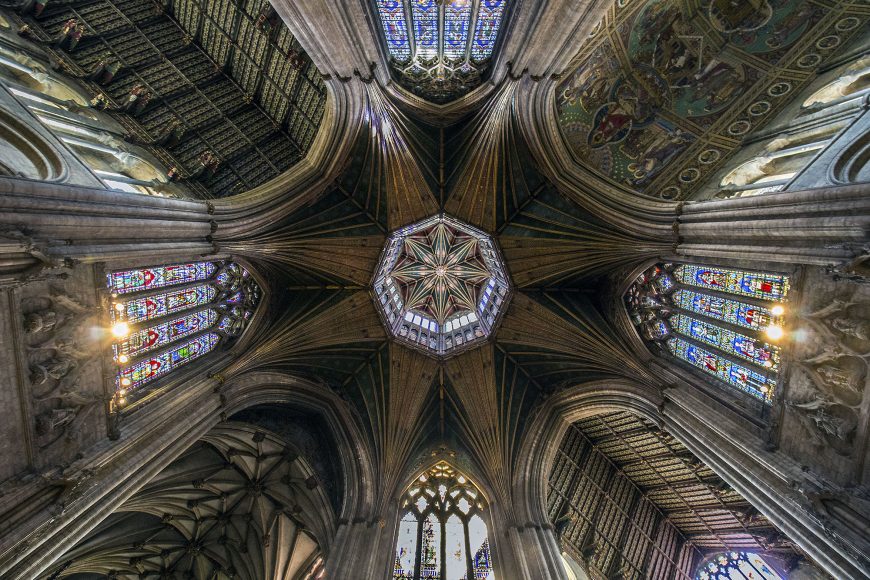

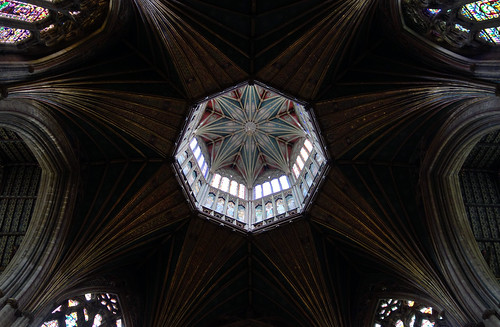

Though this collapse was devastating, it made room for one of the most remarkable structures of the English Middle Ages. Alan of Walsingham, sub-prior and sacrist of Ely, quickly initiated the building of a new tower—a tall, octagonal structure (often referred to as “the Octagon”) surmounted by a tower made of timber clad with lead. This type of tower is called a lantern because it is pierced to allow light in. Vaults with tiercerons spring from the base of the Octagon, creating a star-like effect when one looks up.

In the supporting structure below, Etheldreda was commemorated with capitals depicting scenes from her life. These include her marriage to Igfrid, and her rest on the way from Northumberland to Ely. The Octagon, from floor to the central roof boss, is 142 feet tall, the same height as the Pantheon in Rome. This correspondence may have been intentional, since the Octagon is like a Gothic version of the Pantheon’s incredible dome, and the tower above it delivers light throughout, like the opening of the Roman temple.

Once the Octagon was completed, attention was turned back to the Lady Chapel. A Lady Chapel is a space dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and this one is especially clear in its depiction of her life and miracles. The chapel, built in the Decorated Style, is rectangular, and its elevation is composed of a dado and clerestory. A series of niches encircle the room, forming the dado.

Each niche is protected with a nodding ogee canopy and ornamented with relief sculpture relating to the Virgin. It has been observed that the sculptural niches of the dado have a vulvular shape, perhaps not coincidental given that the chapel celebrates the Virgin Mary, whose chief contribution to Christian history was giving birth to Jesus.

The Lady Chapel was interrupted by the collapse of the central tower, and its progress may have been troubled again by the Black Death, which struck England in 1348. On the western side of the chapel, the nodding ogees of the dado flatten, and the diaper-work is halted. The vault fits uneasily on the chapel. Scholars suspect that some of the sculptors and masons at Ely may have fallen victim to the plague, leaving the lavish project to be completed by their less adept colleagues.

Iconoclasm in the Ely Lady Chapel

Although the Ely Lady Chapel is one of the most beautiful interiors of English medieval art, it’s also one of the most heavily destroyed. During the English Reformation, the sculptures were mutilated because religious imagery was thought to be idolatrous. The images were taken from their niches, and the colorful stained glass that would have filled the windows was destroyed. Some sculpture remains in the life of the Virgin series on the dado, but many have been stripped of their heads or more. Traces of polychromy remain, but are but a pale shadow of the formerly brilliant space.

The end of the Middle Ages

After the Black Death, a final style of the English Middle Ages emerges as the primary mode of building. This is called the Perpendicular Style because, unlike the flowing, undulating curves of the Decorated Style that preceded it, it emphasizes straight lines and vertical projections. The Perpendicular Style took hold in the second half of the fourteenth century, and continued through the remainder of the Middle Ages—almost two hundred years!

Bishop Alcock’s chantry chapel was built in the Perpendicular Style between 1488 and 1500. A chantry chapel is a space devoted to praying for an individual or a family in order to shorten their time in purgatory. Purgatory was understood to be a fiery place where souls went after death, but unlike hell, one could eventually leave purgatory after serving the required amount of time necessary for sins committed during life. A reduction of one’s sentence in purgatory could be achieved, either during life from the acquisition of indulgences, or in death if one’s loved ones or the executors of their wills prayed for them and ensured that masses were said in their honor.

Alcock is likely to have planned the chapel himself—he had been the Controller of the Royal Works and Buildings under King Henry VII. The chapel is cordoned off from the north aisle with a microarchitectural screen with statue niches that are now empty. Though this screen is extremely intricate and beautifully carved, it doesn’t quite fit in the space allotted for it. Prior to becoming bishop of Ely, Alcock had held the same post at Worcester Cathedral. It is thought that the chapel may have been planned for a large space there, but was instead jammed into tighter accommodations at Ely. Within the chapel is Alcock’s tomb, in a niche, and an altar so that Masses could be said for his soul. Alcock’s memory was also made explicit with the use of his rebus with a cock (rooster) atop a globe, and his coat of arms, three cocks.

A ship of four styles

The “ship of the Fens” is a wonderful example of the evolution of English architectural style in the Middle Ages: from Romanesque to Early English Gothic, Decorated, and Perpendicular. The people who built churches in the Middle Ages wouldn’t have thought of themselves as building in these styles, however—these are names given by historians in the nineteenth century to describe them retrospectively. The builders themselves would have thought of what they were building simply as “current.” Although Etheldreda sought refuge her marriage in the quiet, eel-filled marshes of Ely, the Middle Ages saw this site develop into a far more elaborate space than she could possibly have imagined.

Additional resources:

Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland entry on Ely Cathedral

Illustrations for some definitions borrowed from the Glossary of Medieval Art and Architecture.

John Maddison, Ely Cathedral: Design and Meaning (Ely: Ely Cathedral Publications, 2000).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Ely Cathedral’s Lady Chapel

by HENI TALKS

Paul Binski - Ely Cathedral's Lady Chapel: Devotion and Destruction from HENI Talks on Vimeo.

Ely Cathedral’s Lady Chapel was one of the most splendid artistic and architectural achievements of medieval England. The Catholic chapel’s lavishly painted sculpture and stained glass, devoted to the Virgin Mary, moved pilgrims to a religious frenzy. But when Protestants began to call for a ‘purer’ vision of the Christian faith in the 16th and 17th centuries, this same quality triggered repulsion. During the hundred years of the English Reformation, the chapel was scraped, scrubbed and smashed of its extravagance.

Art Historian Paul Binski believes it is possible to recover the Lady Chapel’s former opulence in the imagination. His talk gives an insight into the psychology behind Ely’s splendour, and the idea that art can be so powerful as to provoke violence – something we still see in headlines today.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

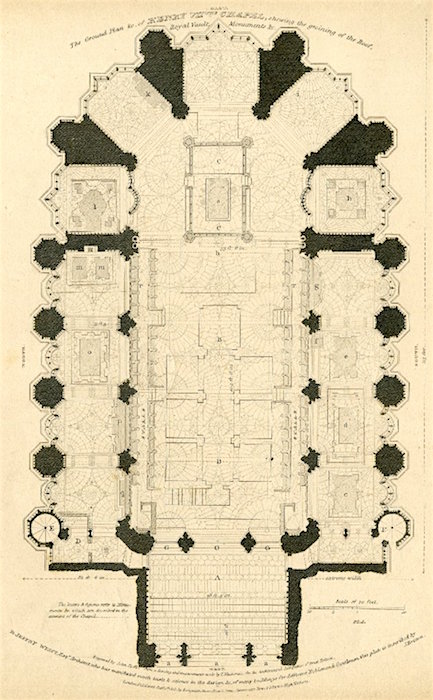

Henry VII Chapel

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Henry VII Chapel, Westminster Abbey, London, begun 1503. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

The Wilton Diptych

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): The Wilton Diptych, c. 1395-99, tempera on oak panel, 53 x 37 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Gothic art in Germany, Italy, and the Czech Republic

The Gothic style spread across Europe, where artists produced sculpture, painting, and architecture for both Christian and Jewish patrons.

c. 1235 - 1500

Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Saint Francis Altarpiece

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Saint Francis Altarpiece, c. 1235, tempera on wood, 5′ high (San Francesco, Pescia, Italy)

Inventing the image of Saint Francis

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): St. Francis and scenes from his life, 1240s-1260s, panel (Bardi Chapel, Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Porta Sant’Alipio Mosaic, c. 1270-75, Basilica San Marco, Venice

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): The Porta Sant’Alipio Mosaic, c. 1270-75, Basilica San Marco, Venice, an ARCHES video speakers: Dr. Elizabeth Rodini, Andrew Heiskell Arts Director at American Academy in Rome and Dr. Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Röttgen Pietà

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Röttgen Pietà, c. 1300-25, painted wood, 34 1/2″ high (LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn)

An emotional response

It is hard to look at the Röttgen Pietà and not feel something—perhaps revulsion, horror, or distaste. It is terrifying and the more you look at it, the more intriguing it becomes. This is part of the beauty and drama of Gothic art, which aimed to create an emotional response in medieval viewers.

Earlier medieval representations of Christ focused on his divinity (left). In these works of art, Christ is on the cross, but never suffers. These types of crucifixion images are a type called Christus triumphans or the triumphant Christ. His divinity overcomes all human elements and so Christ stands proud and alert on the cross, immune to human suffering.

Triumphant Christ / Patient Christ

In the later Middle Ages, a number of preachers and writers discussed a different type of Christ who suffered in the way that humans suffered. This was different from Catholic writers of earlier ages, who emphasized Christ’s divinity and distance from humanity.

Late medieval devotional writing (from the 13th-15th centuries) leaned toward mysticism and many of these writers had visions of Christ’s suffering. Francis of Assisi stressed Christ’s humanity and poverty. Several writers, such as St. Bonaventure, St. Bridget of Sweden , and St. Bernardino of Siena, imagined Mary’s thoughts as she held her dead son. It wasn’t long before artists began to visualize these new devotional trends. Crucifixion images influenced by this body of devotional literature are called Christus patiens, the patient Christ.

The effects of this new devotional style, which emphasized the humanity of Christ, quickly spread throughout western Europe through the rise of new religious orders (the Franciscans, for example) and the popularity of their preaching. It isn’t hard to see the appeal of the idea that God understands the pain and difficulty of being human. In the Röttgen Pietà, Christ clearly died from the horrific ordeal of crucifixion, but his skin is taut around his ribs, showing that he also led a life of hunger and suffering.

Pietà statues appeared in Germany in the late 1200s and were made in this region throughout the Middle Ages. Many examples of Pietàs survive today. Many of those that survive today are made of marble or stone but the Röttgen Pietà is made of wood and retains some of its original paint. The Röttgen Pietà is the most gruesome of these extant examples.

Many of the other Pietàs also show a reclining dead Christ with three dimensional wounds and a skeletal abdomen. One of the unique elements of the Röttgen Pietà is Mary’s response to her dead son. She is youthful and draped in heavy robes like many of the other Marys, but her facial expression is different. In Catholic tradition, Mary had a special foreknowledge of the resurrection of Christ and so to her, Christ’s death is not only tragic. Images that reflect Mary’s divine knowledge show her at peace while holding her dead son. Mary in the Röttgen Pietà appears to be angry and confused. She doesn’t seem to know that her son will live again. She shows strong negative emotions that emphasize her humanity, just as the representation of Christ emphasizes his.

All of these Pietàs were devotional images and were intended as a focal point for contemplation and prayer. Even though the statues are horrific, the intent was to show that God and Mary, divine figures, were sympathetic to human suffering, and to the pain, and loss experienced by medieval viewers. By looking at the Röttgen Pietà, medieval viewers may have felt a closer personal connection to God by viewing this representation of death and pain.

Altneushul, Prague

In architecture, there is often a dominant mode of design in a given country or region at a particular moment in history. In central and western Europe during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it was customary to use Gothic elements such as pointed arches, rib vaults, and thin walls filled with stained glass.

But what about minority groups? Did they follow the trends of the majority or were they told what and how to build by the majority culture? Did the minorities have architects of their own on whom to rely, or were the minority members excluded from certain professions? We know about exclusion and discrimination from modern history. But what happened in the later middle ages?

Jews in Medieval Europe

For centuries, Jews were the most noticeable minority in Europe. They lived only in certain regions, and were excluded from others. Their numbers were usually restricted, even in places where they were allowed to live. Nevertheless, Jews were useful members of society, in part because most Jewish men were literate—they were, and still are, expected to read their prayers (poor Roman Catholics had no schools and relied on priests to read on their behalf). Literate people could be useful in commerce and in keeping records, so some rulers allowed Jews to live in their cities. Often, there was a district designated for Jews, perhaps near the commercial district of a city, near the city walls, or near the palace of the ruler whom they served, (there were formal walled ghettoes only from the mid-sixteenth century onward).

Synagogue architecture

Every Jewish community had to have a place of worship, called a synagogue (from a Greek word related to assembling). Only a few rules governed the design of a synagogue; these rules were found in the Talmud. Later congregations of Jews adhered to these rules as best they could, despite the restrictions on their residence and use of land. Ideally, a synagogue’s focal point, the end of the building’s central axis, would face Jerusalem (to the southeast from the city of Prague).

The synagogue would contain carefully hand-written scrolls of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible that were held in chest known as a Torah ark when not in use. The ark was located at the building’s focal point. When the scrolls were removed from their storage chest, they would be carried ceremoniously to the center of the synagogue where the elders of the congregation would mount a low platform (bimah) and place the scrolls on a reading table. It would be an honor to be called to read to the congregation. In addition, no one was allowed to live above the synagogue; religious activity was to have pride of place and women would not occupy the same part of the building as men in order to avoid distracting the men from their prayers. Animals and other unclean things were not be allowed to defile the synagogue interior.

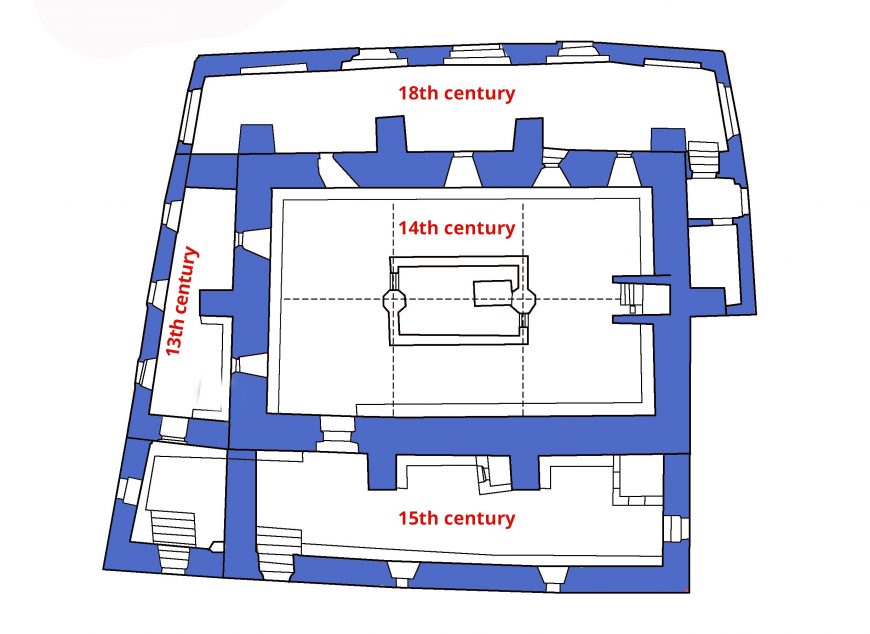

The Altneushul: a Gothic synagogue

An important late medieval synagogue in Prague is called the Old New Synagogue because the city later gained a newer New Synagogue. It is generally known as the Altneushul in Yiddish. It seems to have originally been a small rectangular building erected in the thirteenth century, but late in that century or in the next one, the original synagogue was enlarged. Both stages of construction were apparently designed and built by Christians, because Jews were either formally or tacitly excluded from the guilds (trade associations) of the building crafts. An architect who at other times worked on churches seems to have been in charge because ornamental details are similar to those of a local church; the architect was therefore almost certainly Roman Catholic.