13.5.7: South Asia (I)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 88701

South Asia

Indigenous traditions & cross-cultural interaction inspire much art and architecture from the region

4th century B.C.E. – 1799 C.E.

A beginner's guide

A brief history of the art of South Asia: Prehistory – c. 500 C.E.

Art is a wonderfully tangible pathway to past cultures. In the large collar of a tiny terracotta dog from Harappa, in present-day Pakistan, we learn about people and their dogs four thousand years ago. In beds made of stone inside rock-cut viharas (monastic houses) in the hillside of Ajanta, in India, we glimpse the lives of Buddhist monks in the first century B.C.E. And in pieces of furniture fashioned from ivory and bone found in Begram in Afghanistan, we get a taste of the luxury and artistic skill that people — much like you and I — cherished nearly two millennia ago.

A few considerations

South Asia (according to the modern designation of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation), includes the following countries:

|

|

In this brief introduction to the art and cultures of South Asia from prehistory to c. 500 of the Common Era, we refer to these countries to aid in geographically orienting you to the material culture discussed. It is important to remember, however, that over the course of history, the sovereign nations of South Asia experienced both distinct and shared histories, and these often do not correspond to modern-day borders.

Definition: Material culture

Material culture refers to art, architecture, written records, and everyday objects used by a culture.

The artifacts, coins, and written records of empires and kingdoms that emerged and dissolved throughout history help us anchor the boundaries of people who shared a common lifestyle, language, and religion. In the study of prehistoric artifacts, other factors — such as shared technologies and ritual practices — help us recognize patterns of living that indicate geographically coherent cultures and societies.

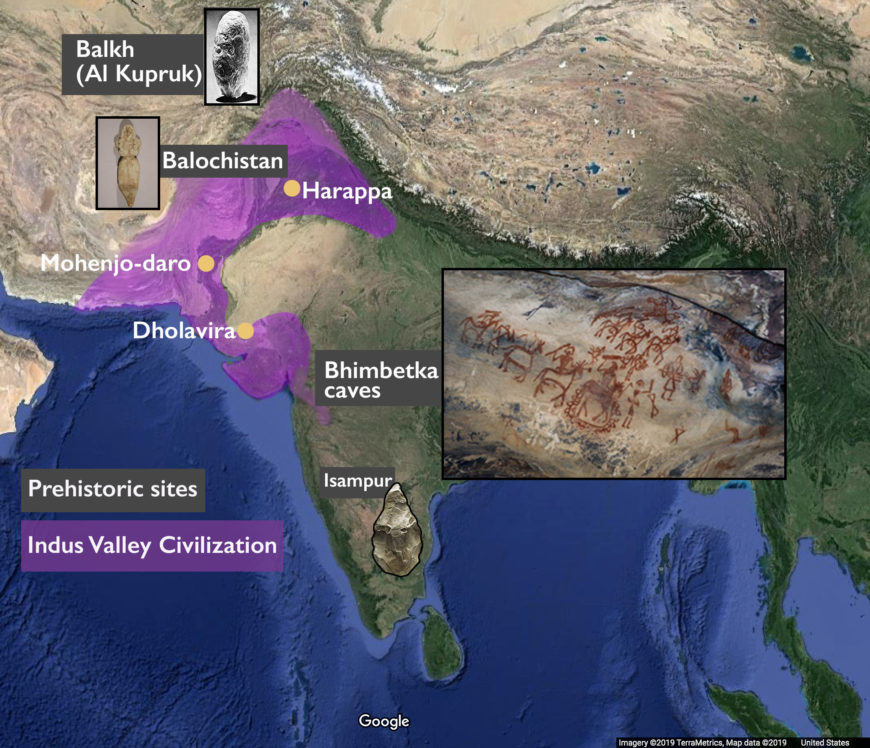

Topography too (marked in yellow in the map above) influenced cultural and political histories. The Hindu Kush mountain range (in Afghanistan), the Himalayas (in Bhutan, Nepal, India, and Pakistan), the Thar desert (in northwestern India), the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea, and the Lakshadweep Sea that surround the Indian peninsula, and the Palk Strait between India and the island nation of Sri Lanka, all played important roles in shaping the histories and the art histories of South Asia.

Prehistory

Archaeology can help us understand much about prehistoric civilizations. A stone tool, discovered in Isampur in India (see inset in the map below), for instance, confirms human settlement in the region as early as 1.1 million years ago.

Definition: Prehistoric

Prehistory refers to a time before written records.

Some of the earliest portrayals of ancient peoples in South Asia are found in the Bhimbetka caves, dated c. 9000 B.C.E., in central India. The paintings show figures dancing and humans hunting (see inset in the map above), as well as a person being hunted or attacked by an animal. Excavated tools, pottery, and figurines of animals and humans found in Balochistan, Pakistan, also tell us about the interests and activities of people from c. 7500 – 2500 B.C.E. In the inset in the map above is an artifact from Balochistan that is thought to represent a fertility or cult goddess. From a time relatively more recent — c. 20,000 B.C.E. — is a limestone pebble with a face incised on it (inset in map above) from the archaeological site of Aq Kupruk II in the Balkh province of Afghanistan. The pebble poses interesting questions — who made it? And why?

The Indus Valley Civilization

Between 2600 and 1900 B.C.E., several settlements (see map 2 above) thrived around the river Indus which extends from the Tibetan plateau and flows into the Arabian Sea. These settlements — Indus cities have been excavated in Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan — are known collectively as the Indus Valley Civilization.

Large sites such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in Pakistan have revealed highly efficient urban-planning, well-designed homes and neighborhoods laid out on a grid pattern, granaries, and public buildings all built with uniformly sized bricks. The Indus people were skilled in the management of natural resources; the site of Dholavira in Gujarat, India for instance, had a sophisticated system of water management. A complex writing system was also in use in this period, although sadly, the Indus script remains undeciphered.

Miniature terracotta figurines of a range of animals including the rhinoceros, birds, and dogs, and bullock drawn carts with drivers (see below) have been excavated from Indus sites. Whether they represent votive images or are simply children’s toys is as yet undecided. Board games, jewelry made of shells and beads, and stone and bronze figurines have also been discovered as have many steatite seals. These seals may have been used in trade and ritual and are distinguishable by their engravings of animals, humans, possibly divine beings, and, on occasion, unicorns!

The Vedic period

By c. 1300 B.C.E., speakers of Sanskrit (known as the Aryas) had settled in the northwest region of the Indian subcontinent. The Rigveda, the earliest of four Vedas (Sanskrit for “knowledge”) — a compendium of sacred scriptures on ritual, liturgy, and moral principles — is dated to this period. [1] The Vedas were a significant influence on the development of the Hindu religion. Like the material artifacts from the Indus Civilization above, the Vedas also carry glimpses of life in the Vedic period. We learn of the people who lived in the region prior to the arrival of the Aryas, as well as details on societal relationships, daily life, and the worship of gods and goddesses from Vedic hymns.

Scholars have been able to discern the eventual movement of people to the Gangetic plains of India (see map 5 below) from the three later Vedas — the Samaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda. [2] Another important set of sacred texts, collectively known as the Upanishad, were composed sometime between the seventh and the fifth centuries B.C.E., and served as an elucidation of the Vedas. [3]

Buddhism

The Magadha region (roughly centered around Bihar and northeastern India, see map 5 below) would become a place of socio-religious debate and the birthplace of two major religions — Buddhism and Jainism — that were born in critical reaction to Vedic traditions. Some scholars have suggested that existing spiritual traditions in Magadha — the belief in rebirth and karma, for instance, was absorbed into Brahmanism (a precursor to Hinduism), Buddhism, and Jainism. [4]

Born Siddhartha Gautama in Lumbini, in present-day Nepal, the exact date of the Buddha’s birth is not known, but scholarly consensus dates his death around c. 400 B.C.E. [5] The Buddha’s teachings offered people a new path to salvation that was different from the ritual-based practices of the Vedic religion. You can read about Brahmanic Hinduism and Buddhism, including the life of the historic Buddha, jatakas, and the Buddha’s teachings here.

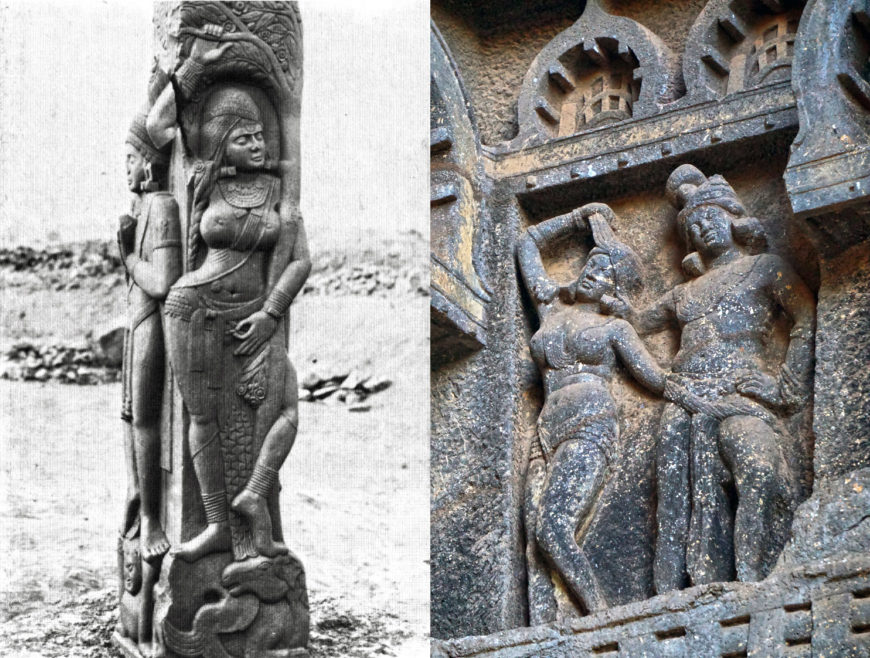

Buddhist monastic sites were adorned with narrative panels that celebrated the life of the Buddha — first in aniconic form and later in iconic form — as well as with a wealth of sculptural representations of men, women, animals, architecture, plants, and nature spirits, including yakshis (female goddesses), yakshas (male gods), and mithuna (couples) in a nod to pre-Buddhist traditions of reverence for fertility spirits.

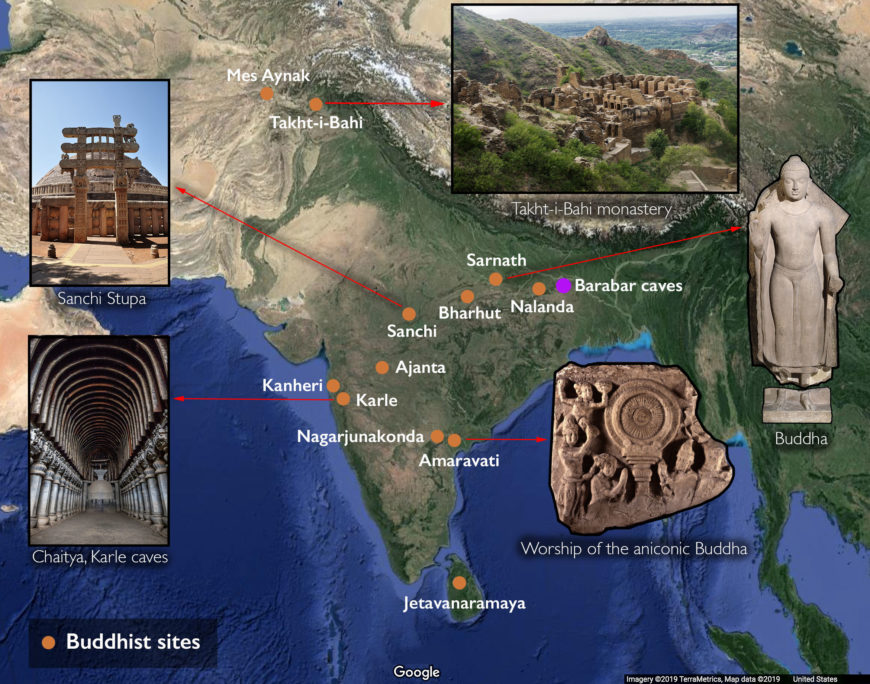

According to tradition, on his death, the Buddha’s cremated remains were distributed amongst nine clans. These relics came to be deposited in stupas (burial mounds) where they were then worshipped by the Buddha’s followers. By the early centuries of the Common Era, Buddhist sites were found throughout India, Afghanistan, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (see map 4).

Jainism

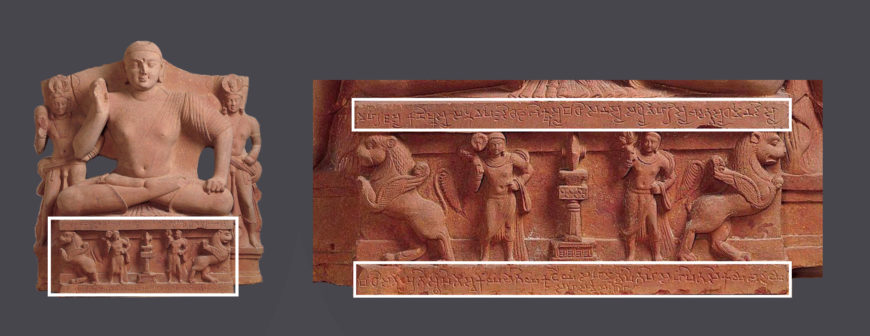

The founder of the Jain religion, Mahavira, is believed to be a contemporary of the Buddha. Like Buddhism, Jainism offered a path to salvation that was unencumbered by ritual. In Jain tradition, the twenty-four Jinas (Sanskrit for “victor”) who have overcome karma (the sum of a person’s actions) through a life of spirituality and goodness serve as role models for Jains and the path to salvation. Mahavira was the twenty-fourth and final Jina.

Jinas are often shown in the meditative posture — either seated or standing — and emphasize austerity, immobility, and asceticism. Jain sacred imagery also involves images of nature deities as well as gods and goddesses such as Indra and Saraswati who are important deities in Hinduism. Images of the Jina may have the srivatsa (an ancient symbol) marked on their chest (see image on right, above), which distinguishes them from sometimes visually congruent images of the Buddha.

The Mauryas

In c. 326 B.C.E., Alexander of Macedonia invaded the Indian subcontinent. Alexander reached as far as the river Beas in present-day Punjab, India (see map 3) before he was forced to acquiesce the exhaustion of his army and their wish to return home. Alexander’s incursions had a lasting impact on South Asian history. One of his generals, Seleucus Nicator, would become the ruler of the Seleucid Empire which stretched from Anatolia to Afghanistan and Pakistan, including parts of the Indus Valley. Seleucus’s ambitions for more territory was curbed, however, by Chandragupta of the Maurya dynasty.

A treatise on war and diplomacy composed by the minister Kautilya in Chandragupta’s court offers a remarkable glimpse into the Mauryan kingdom and its policies. Along with rules for military regiments and economic strategy, this treatise, the Arthashastra, details policies on the exemption of taxes in times of disaster, guidelines for the use of state resources for the care of elephants and horses, and the protection of natural resources such as forests.

Much of Chandragupta’s life is misted by legend. What is certain is that he was a formidable ruler and warrior and that the Maurya kingdom under his rule was a prosperous one. Chandragupta’s son Bindusura maintained his father’s territorial gains, but his life too is poorly documented in contemporary accounts. According to tradition, Chandragupta converted to Jainism at the end of his life.

We have far more information about Chandragupta’s grandson, the emperor Ashoka. Ashoka too was a formidable ruler, but he vowed to rule, later in life, through non-violent means in adherence with the teachings of the Buddha. Ashoka helped spread Buddhism across the entire Indian subcontinent with the installation of pillars that proclaimed dhamma (Buddhist law). In addition to Buddhist philosophy, these edicts also detailed state provisions on social welfare for both people and animals.

Ashokan edicts have been found (see map 3) in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, and often in the language associated with the people who lived in those areas. Pillars were inscribed in Prakrit in the Kharoshthi and Brahmi scripts, Greek, and Aramaic, as well as in bilingual scripts. While we have not found Ashokan edicts in Sri Lanka, it is believed that Buddhism also spread to the island during Ashoka’s reign in the third century B.C.E. More edicts are likely to be discovered in the future; a team of archaeologists at UCLA is using geographic modeling to help accomplish just that.

Buddhist Monastic Sites

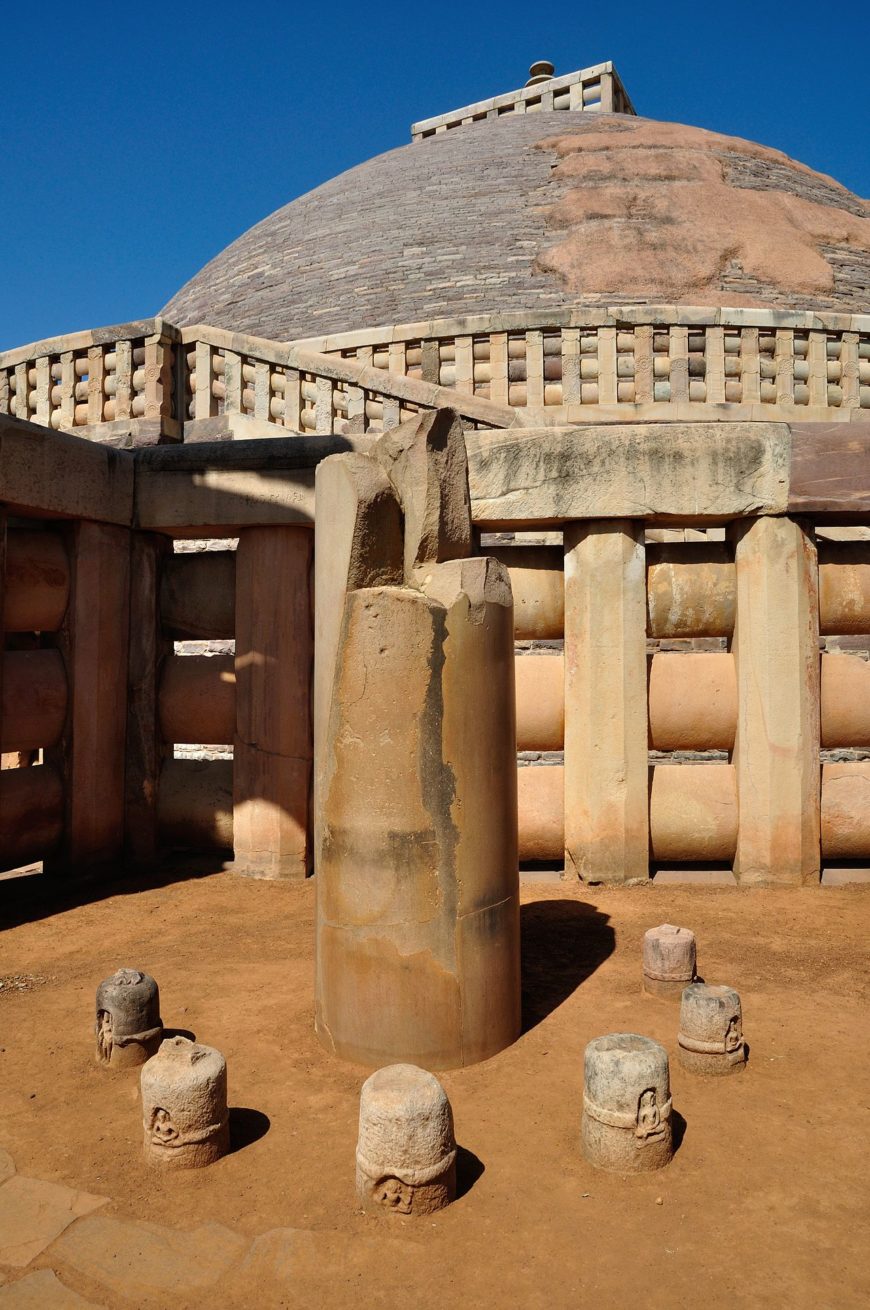

A now broken Ashokan pillar at the great stupa at Sanchi, a Buddhist complex associated with the patronage of the emperor, was retained when the stupa was expanded to twice its size and faced with stone in the first century B.C.E. Stupas are quintessential monuments to the memory of the Buddha and are burial mounds for the relics of other important persons. Stupas were often built in the midst of large monastic settlements known as samgha(s).

As Buddhism spread, monastic complexes were established in sites in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Nepal. The stupa of Jetavanaramaya is located in one of the oldest known samghas in Sri Lanka, and dates to the third century C.E. It is believed, however, that the oral Buddhist canon was written down during the reign of Sri Lankan king Vatthagamini (29 – 17 B.C.E.). [6] Other examples of well-known and early Buddhist sites include Amaravati, Bharhut, and Nagarjunakonda in India, Takht-i-bahi in Pakistan, and Mes Aynak in Afghanistan (see map 4).

Monastic sites often show multiple phases of construction spanning centuries, indicating the sustained patronage and popularity of Buddhism. Nagarjunakonda, in particular, also preserves a record of the expanding footprint of monastic complexes with its multiple stupas, prayer halls, temples, and housing accommodations.

Buddhist sites regularly received the patronage of both Buddhist and Hindu kings, as well as that of ordinary people, including Buddhist monks and nuns, merchants, and travelers. Sanchi is remarkable for the information it preserves on ordinary people. Inscribed on the great stupa are 631 donative inscriptions that tell us about the people — from merchants to monks to nuns — who contributed to the reconstruction and beautification of the stupa in the first century B.C.E. [7]

The stupa’s four extraordinary gateways (torana), once carried six images each of yakshis. These figures served as architectural brackets and as symbols of fertility — in obeisance to the auspicious quality associated with images of women on sacred structures. [8]

Amaravati, Nagarjunakonda, Sanchi, and countless other Buddhist monastic complexes were built at crossroads and close to trade-routes across the Indian subcontinent. This allowed monasteries to be of service to weary travelers and adhere to the Buddha’s instruction on the importance of sharing his teachings far and wide.

Buddhist samghas (monastic complexes) were also established in rock-cut caves. There are a large number of Buddhist rock-cut monastic caves in India — ranging from elaborately decorated to simply appointed. Caves hold a special significance in Buddhist tradition; according to Buddhist belief, when the Hindu god Indra went to visit the Buddha, he found him meditating in a cave.

Some of the most elaborate rock-cut caves are found at Ajanta and are dated to the fifth century of the Common Era, while a less embellished but no less stunning (rock-cutting is no easy task!) monastic complex can be found in the Barabar caves, dated to the third century B.C.E., in Bihar. The facade of the Lomas Rishi cave (image below) displays one of the earliest known representations of the “chaitya-arch” — an ornamented ogee shaped arch that replicated wooden construction in stone and became a commonly used feature in Buddhist rock-cut architecture in India. While the cave complex at Barabar belonged to an ascetic community known as the Ajivikas rather than the Buddhists, nearby inscriptions indicate that this community enjoyed the patronage of emperor Ashoka.

On occasion, rock-cut caves and sculpture preserve glimpses of older architectural traditions. In the caves of Karle, Maharashtra, for instance, we find the original wooden beams from the first century B.C.E.; the use of wood (see inset in map 4, above) in the ceiling ribs was a purely decorative choice that imitated the style of wooden Buddhist chaityas (Buddhist chapels).

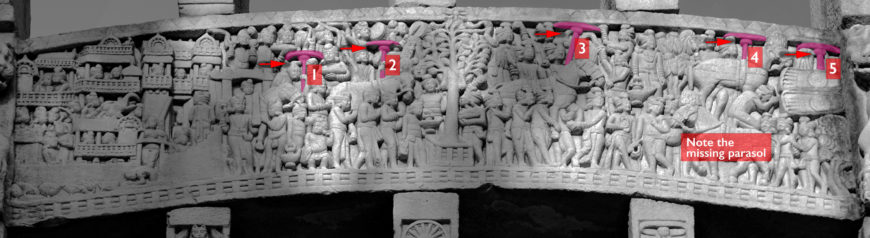

The adornment of rock-cut caves followed the same temporal progression of representing the Buddha — i.e., from aniconic (as emblems) to iconic (in human form). Whereas earlier Buddhist sites employed anionic symbols such as parasols, footprints, and even stupas to signify the presence of the Buddha, in time, representational imagery of the Buddha became the norm. The image below from Sanchi stupa shows an episode from the Buddha’s life known as the Great Departure. It represents the moment when the Buddha left his life in the palace for good.

The parasols (shown in pink) indicate the Buddha’s movement from left to right. Once the Buddha disembarks at his destination and the horse returns to the palace, the Buddha’s absence on the horse is signaled by the absence of the parasol. The parasol remains with the Buddha who is now signified by a set of footprints. Also note how as the Buddha proceeded quietly into the night, the attendants helped carry the horse!

In general, in earlier rock-cut sites, we find stupas made of solid-rock serving as aniconic emblems of the Buddha and the focus of devotion. In later rock-cut chaityas, an image of the iconic Buddha was attached to the solid stupa (see image above), or the stupa was replaced altogether by the image of the Buddha. You can read about the complex ways in which the Buddha was portrayed in art here.

Despite the popularity of Buddhism in the centuries around the start of the Common Era, other religions continued to thrive. Two important Sanskrit Hindu epics — the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, for instance, are thought to have been composed in c. 300 B.C.E. — 300 C.E. and 200 B.C.E. — 200 C.E. respectively. [9]

The Kushans

Between the second century B.C.E. and the third century C.E., the Kushan empire became a dominant force in the northwestern part of the subcontinent. The Kushans were active in both sea and land trade and had capitals in Kapisa (near Kabul, Afghanistan), Peshawar, Pakistan and in Mathura, India. Kushan territory under the rule of the third emperor Kanishka (2nd century C.E.) also included, in addition to north India, what is today parts of Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

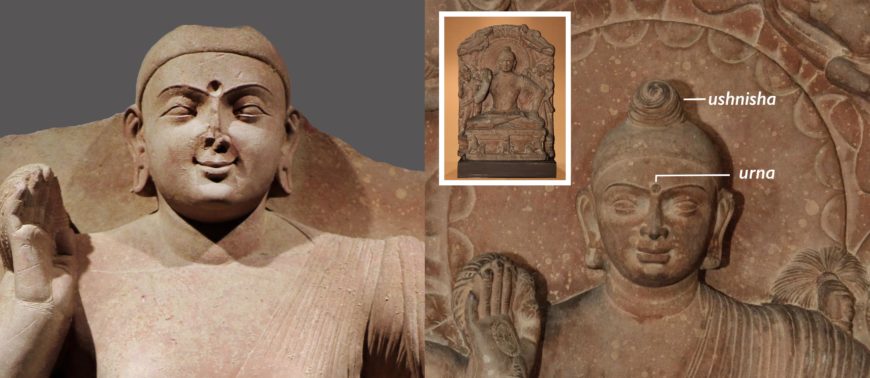

Two types of iconic Buddha images were produced during the Kushan period — the Gandharan and the Mathuran Buddhas — distinguishable by both style and medium. Just as Mathuran Buddhas followed the style of local sculptural traditions, in Gandhara, images of the Buddha followed a Greco-Roman aesthetic, thanks in part to the presence of plentiful Hellenistic imagery and Macedonian and Parthian influences in the region.

Kushan emperor Kanishka is considered second only to Ashoka for his contribution to Buddhism. He is credited with the building of an enormous stupa (reportedly somewhere between 295 and 690 feet high) with multiple stories and thirteen copper umbrellas. Only the foundation of the building — itself 286 feet long — survives today in Shahji-ki-Dheri, outside Peshawar, Pakistan. [10] A gold coin has survived that was minted during Kanishka’s reign and likely shows that ruler.

Hundreds of ivory and bone furniture pieces, figurines, and a large number of practical and extravagant wares, produced in South Asia and as far away as China, Rome, and Roman-Egypt, dated to the Kushan period, have been discovered in Begram, Afghanistan. These objects tell us about the kinds of goods that travelled the Silk Road in the first and second centuries. By the second century, Buddhism had also travelled and spread farther east to Central Asia and China via these same routes. The earliest known translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese is dated to the second century C.E.

The golden age

By the early centuries of the first millennium, the Vedic religion had evolved into the Hindu religion. While a core tenet of Hinduism — the concept of the Brahman (omnipresent consciousness) — had already been formulated in the Upanishads, many of the gods and goddesses that we see in Hindu art are found in the Puranas (ancient stories) that were composed in this period.

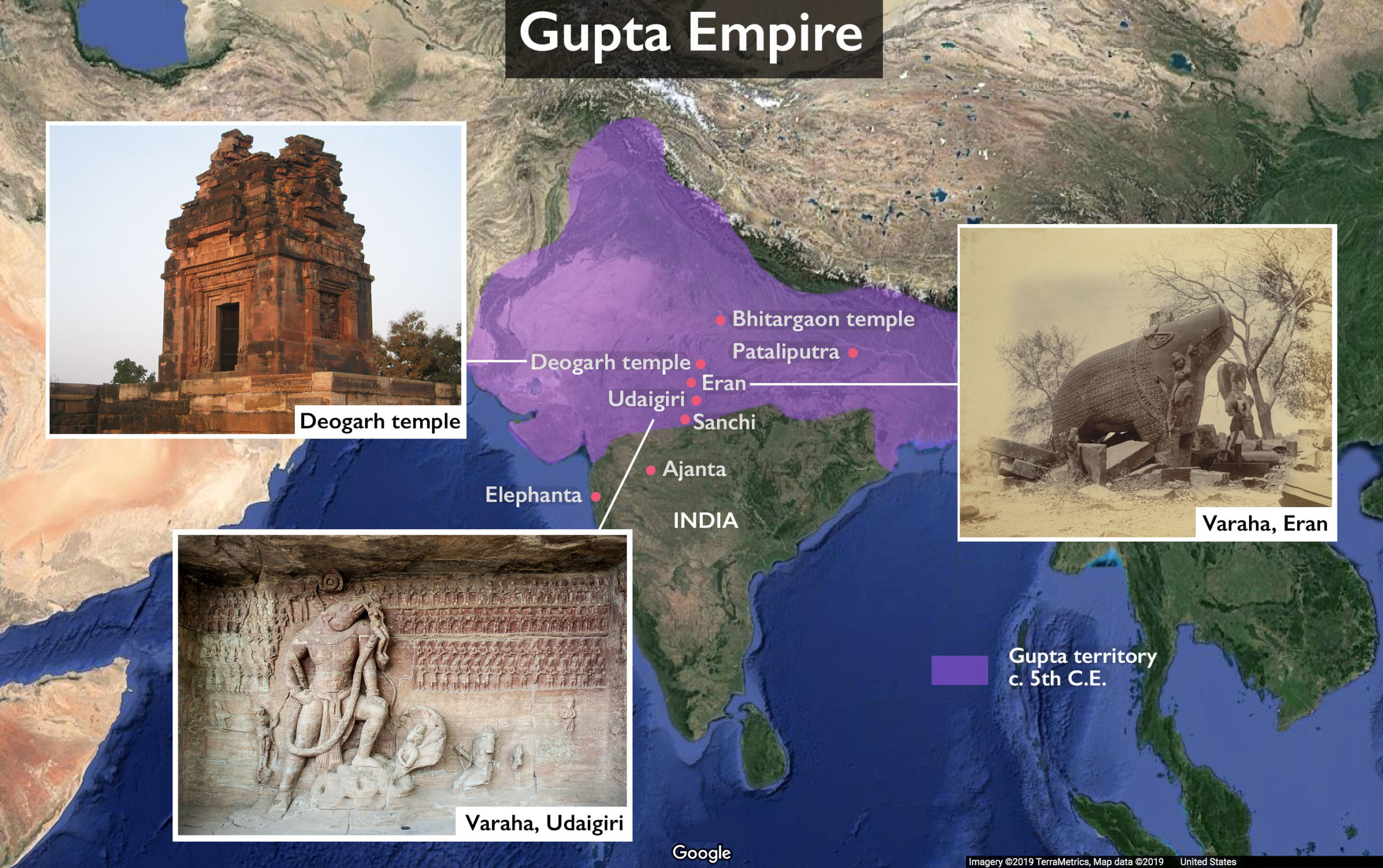

The rise of the Gupta dynasty (c. 320 – 647) marked an important time for art, architecture, and literature. It was also a period of strong global trade; scholars believe that the Gupta sculptural and temple-building style can be found in the early medieval remnants of Buddhist and Hindu art and architecture in Southeast Asia. A coin shows king Samudragupta, one of the Gupta dynasty’s most successful rulers and one who greatly expanded the dynasty’s power and territories. The inclusion of a goddess on the reverse side of the coin implies divine kingship in an effort to suggest that the king’s rule was mandated by the gods.

Some of the most celebrated writers and composers of drama, poetry, and prose, lived in this period — Kālidāsa and Bānabhatta, among them. The number zero was invented as were Arabic numerals, which were referred to by Arabs as hindisat (“the Indian art”). This was also the era of great scientists; the astronomer Aryabhata in the sixth century calculated the solar year at 365.3586805 days and theorized that the earth rotated on its own axis. [11]

It was also during the Gupta period that a new type of Buddha image — the Gupta Buddha emerged. Buddha images in this period continued to be produced in Mathura, but also in Sarnath and in Nalanda (see map 4). Each area had access to quarries of a specific type of stone which have helped art historians determine where an image may have been produced.

Hindu art and architecture also flourished in the Gupta period. One of the most famous religious sites associated with the Guptas is the Udayagiri complex of rock-cut caves in Madhya Pradesh (see map 5). The Udayagiri Caves are made up of twenty caves, nineteen of which are dedicated to Hindu gods and date to the fourth and fifth centuries. There is also one Jain cave that is dated to the early fifth century.

Throughout the Gupta period, regional kingdoms led by independent rulers prospered. In most instances, there was also an easy relationship between the Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain religions; as an example, the famous Buddhist rock-cut caves at Ajanta in Aurangabad enjoyed the patronage of the Hindu Vakataka dynasty.

In contemporaneous South India, the culturally cohesive region known as Tamilakam (see map 5) produced a valuable set of texts known as Sangam (old Tamil for “academy”) literature. These texts were composed in the old Tamil language and are rich in information on ancient South Indian kings, religious devotion, temple building, daily life, and even grammar.

Structural Hindu temples were also built in this period, although the choice of brick and other more perishable construction materials has meant that most have not survived. An exception is the brick temple at Bhitargaon in Uttar Pradesh (north India) which is dated to the mid-fifth century (see above). The style and the skill of the architects and builders of Bhitargaon, as well as of Deogarh — a sixth-century structural stone temple also in Uttar Pradesh — suggests that a highly developed tradition of temple building was present by this point in time.

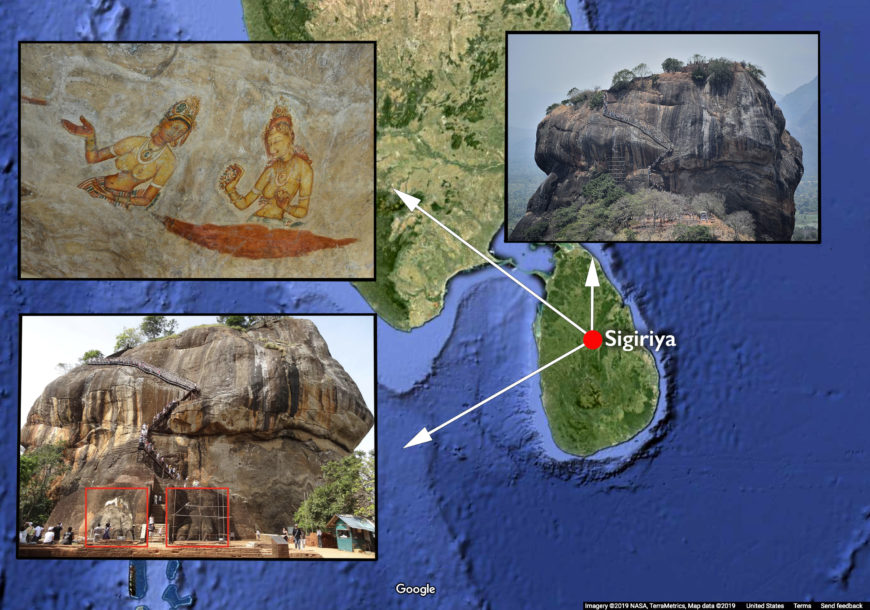

In fifth century Sri Lanka, a ruler named Kassapa built an extraordinary palace fortress atop a hill in his new capital. The site gets its name — Sigiriya — after “lion rock,” thanks to its enormous gateway in the form of a lion, of which only giant paws built from brick survive (see inset in map 6). Kassapa’s palace once included gardens and lakes and dozens, perhaps hundreds of mural figures of women that have been interpreted by scholars as either apsaras (heavenly beings) or ladies-in-waiting. Roughly 22 figures remain today.

Also at Sigiriya is a gallery known as the mirror wall (once a wall with polished plaster) as well as 685 instances of graffiti dating between the eighth and the tenth centuries. [12] Aside from its association with its patron king, Sigiriya is an important site in the history of Buddhism and is mentioned in the Sri Lankan Buddhist chronicle the Culavamsa.

Trade and exchange

Before we move on to the next section of this three-part introduction to South Asia, a word is necessary on the region’s long history of contact and exchange with other parts of the world. The Gupta period enjoyed trade with Southeast Asia and even older networks of trade existed along the Silk Road and in the Indian Ocean. Scholars have also suggested that trade brought beads and precious stones from the Indus Valley to Mesopotamia as early as the third millennium B.C.E.

In the first century of the Common Era, a Greek sailor wrote the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea — a text that provides remarkable details on thriving trade by sea and by land in the Indian Ocean. We learn of routes, the best times to travel, the monsoon winds and their impact on sea travel, the commodities that were traded, the money exchanged, and more.

The Roman historian Pliny the Elder similarly records valuable information in his Historia Naturalis from the year 77 C.E. He reported, for instance, on which pirate-filled ports to avoid in western India and wrote somewhat sardonically of his disdain for his fellow Romans’ obsession with pepper and luxury goods.

Buddhist sites also acknowledge the cosmopolitan milieu of ancient South Asia. At a rock-cut cave in Karle (see map 4), inscriptions dating to the early second century C.E. record gifts of stone pillars by yavanas (foreigners). Roman coins from the first and second centuries have also been found in Nagarjunakonda, as well as near the ancient port town of Muziris in Kerala. In addition, Roman amphorae have been found in the archaeological site of Arikamedu in Tamil Nadu (see map 5).

As Pliny tells us, much also travelled abroad. The most famous of all objects to travel to Rome was an ivory figurine of a woman. A little under ten inches tall, this astonishing figurine with hair and jewelry much like that of the women carved on the toranas at Sanchi somehow survived the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79 C.E. and was discovered in the ashes of Pompeii.

Notes

[1] Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon Press, 1997), 37.

[2] R.U.S. Prasad, The Rig-Vedic and Post-Rig-Vedic Polity (1500 B.C.E. – 500 B.C.E.) (Delaware: Vernon Press, 2015), 107.

[3] Patrick Olivelle The early Upanisads: annotated text and translation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 12.

[4] Johannes Bronkhorst, Greater Magadha: studies in the culture of early India (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 15 – 54.

[5] Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon Press, 1997), 40.

[6] Vidya Dehejia, “On Modes of Visual Narration in Early Buddhist Art,” The Art Bulletin 72, no. 3 (1990): 376.

[7] ibid., 379.

[8] Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon Press, 1997), 65 – 66.

[9] Wendy Doniger, The Hindus: an Alternative History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 693.

[10] Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon Press, 1997), 85.

[11] ibid., 96 – 97.

[12] Joanna Williams, “Construction of Gender in the Paintings and Graffiti of Sigiriya,” in Representing the Body: Gender Issues in Indian Art, Vidya Dehejia ed. (New York: Kali for Women, 1997), 56.

Additional resources

British Museum’s Virtual tour of Amaravati stupa

Catherine B. Asher and Cynthia Talbot, India before Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Frederick M. Asher, “Visual Culture of the Indian Ocean: India in a polycentric world,” Diogenes 58/3 (2011): 67 – 84.

Ute Franke, “Baluchistan and the Borderlands,” in Encyclopedia of archaeology, Deborah M. Pearsall ed. (San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press, c2008).

J. Mark Kenoyer, T. Douglas Price, and James H. Burton, “A new approach to tracking connections between the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia: initial results of strontium isotope analyses from Harappa and Ur,” Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013): 2286 – 2297.

Paul J. Kosmin, Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014).

Yasodhar Mathpal, Prehistoric rock paintings of Bhimbetka, Central India (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1984).

Partha Mitter, Indian Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Jan Nattier, A Guide to the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Traditions: Texts from the Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms Periods (Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, 2008).

Patrick Olivelle and Mark McClish, ed. and trans.,The Arthaśāstra: selections from the classic Indian work on statecraft (Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2012).

Monica L. Smith, Thomas W. Gillespie, Scott Barron and Kanika Kalra, “Finding history: the locational geography of Ashokan inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent,” Antiquity 90 (April 2016): 376 – 392.

Submerged, burned, and scattered: celebrating the destruction of objects in South Asia

A photograph by artist Ketaki Sheth depicts a little girl, wearing a lacy floral dress and standing upon the shoulders of a man, perhaps her father, to get a better view of the surrounding crowd that carries a large sculptural image of the Hindu god Ganesha. Sheth captures a moment of stillness during an otherwise boisterous and energetic occasion: the artist brings us above the crowd and into the clouds that backlight the richly adorned body of the elephant-headed deity—remover of obstacles and son of Shiva and Parvati—on his way toward a body of water for ritual immersion during the annual festival of Ganesha Chaturthi.

Impermanence and belief

The practice of ritually submerging, and thereby destroying, sculptural images of Ganesha during Ganesha Chaturthi represents one of several religious and cultural acts in South Asia which complicate ideas about the value and permanence of material objects. Makers involved in these practices produce objects and artistic depictions with the knowledge that the products of their creative labor are temporary and will be intentionally destroyed or deteriorate over time. In some cases these practices of ritual destruction resonate with ideas about the cyclical nature of time as described in concepts like samsara. In other cases the destruction of an object is symbolic of the removal of evil and the restoration of good in the universe. In still other cases, we find beautifully wrought material objects whose impermanence is embedded in their form and function, much like disposable paper plates.

These examples challenge us to push against the preciousness of objects—an approach that we encounter so often in the study of art—and to rethink the way we value the permanence / impermanence of material things. This call to rethink our valuation of objects is also critical to the decolonizing of the discipline of art history; privileging objects of durable and precious materials over ephemeral works of art (such as things made from unfired clay, paper, or cotton fiber) is in many ways a legacy of British colonial rule on the subcontinent that sought to promote a Eurocentric view and valuation of objects and artistic practices.[1]

For the Ganesha images created in celebration of Ganesha Chaturthi, their destruction is a joyous celebration. Occurring in August or September of each year according to the Hindu lunar calendar, the ritual immersion of Ganesha marks the deity’s birth and symbolic return to the earth. [2] According to legend, Ganesha was created from clay by the goddess Parvati and was given an elephant’s head after his father, the god Shiva, inadvertently beheaded him. Ganesha Chaturthi celebrates the moment when the deity received his elephant head, and his ritual immersion in water each year following ten days of rites is a significant event that bestows blessings on devotees.

Immersion as purification

It is not surprising that worshippers laboriously carry sacred sculptural images or murtis of Ganesha to local bodies of water for ritual immersion. Water is a symbolic purifier in South Asia and used in numerous religious and cultural practices connected with worshipping Hindu gods and goddesses as well as honoring holy figures, saints, and sacred architecture in Buddhist, Christian, Jain, Muslim, and Sikh beliefs. For the Hindu devotees participating in ritual immersion festivals like Ganesha Chaturthi, the water itself is sacred and ultimately connected to the holiest river in India, the Ganga.[3]

Historically, artists made disposable or perishable murtis of the god from unfired clay or low-fired terracotta decorated with natural pigments. [4] These images would slowly dissolve in water and eventually be reincorporated into the ecosystem. However, over the last several decades increasingly larger Ganesha images made from synthetic paints, gypsum plaster (plaster of Paris), and plastic ornaments have become popular, and the heavy metals and toxins associated with these raw materials have leached into India’s waterways, creating dangerous amounts of pollution. [5] Recently, the Government of India’s Central Pollution Control Board established rules requiring that devotees use Ganesha murtis made from biodegradable materials (like terracotta) and have encouraged that ritual immersion practices occur in specially-designated water tanks.

In addition to annual events like Ganesha Chaturthi, the making of temporary, perishable objects and artistic depictions appear on a daily basis in many parts of India through the creation of decorative floor paintings known by various names including alpana, kollam, and rangoli. [6] Typically made by female members of a household or community using rice flour, chalk, powdered pigments, or flowers, the symmetrical forms of these temporary paintings symbolize divine power. They are intended to sanctify a space, and have ancient origins in goddess worship. [7] For special festivals some women create particularly elaborate floor paintings that last for several months or even up to a year. There are many, however, who treat this practice as a daily ritual with the intention that the painting will be swept clean and remade each morning—the epitome of intangible cultural heritage. [8]

Destroying the demon king

A particularly dramatic example of the ritual destruction of objects occurs with sculptural effigies of the demon king Ravana and his demon armies which are burned and physically torn apart during multi-day performances of the Ramacharitamanas, the Hindi version of the story of Rama which is especially popular throughout North India and famously performed in the city of Ramnagar. [9] This performance, known locally as Ramlila, narrates the story of Rama, an earthly form or avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu, who is the beloved king of the city of Ayodhya and husband to Sita, an avatar of the goddess Lakshmi. The Ramacharitamanas, similar to the Sanskrit Ramayana, describes the adventures of Rama, his brother Lakshmana, and Sita during their fourteen-year exile from Ayodhya. The story culminates in a series of battles between Rama and the powerful demon king, Ravana, who has abducted Sita and held her captive at his palace in Lanka.

In the final days of the Ramlila performance, sculptural depictions of Ravana and other demons made from bamboo and paper are set ablaze to symbolize their mythological destruction. The most dramatic moment in the Ramlila performance occurs on Dussehra, an important Hindu festival celebrated throughout India, when participants destroy sculptural depictions of Ravana, sometimes 75-feet tall and filled with firecrackers, to mark Rama’s victory over the demon king and the ultimate victory of good over evil.

In other parts of India, Dusshera is celebrated as a way to mark the goddess Durga’s victory over the buffalo demon Mahishasura, understood by devotees as a mythological act that restores dharma to the universe. Worshippers celebrate Dusshera by creating elaborate temporary altars or pandals for Durga, many of which are then submerged in water on Dusshera, marking the culmination of nine nights of celebration known as Navratri. The pandals made for the worship or puja of Durga are most famously created in Bengal where families, neighborhoods, community organizations, and businesses commission elaborate pandals that incorporate depictions of iconic architecture and motifs from popular culture. [10]

A photograph by artist Raghu Rai depicts the ritual immersion of Durga during a Dusshera celebration in Kolkata. In Rai’s image we see a larger-than-life murti of Durga being carried with bamboo poles to the Ganga by several human figures—a scene that parallels depictions of Ganesha Chaturthi. These human devotees work together to hoist the goddess into the river. We see Durga’s many arms clearly holding the weapons she uses to vanquish Mahishasura and her lion mount or vahana with its mouth agape seated nearby. A nineteenth-century painting of a similar moment suggests earlier practices of this form of ritual immersion. While the focus in the painting is on the elaborately adorned murti of Durga and the human devotees who carry her pandal in procession, in the foreground of the scene appears loose brushstrokes that hint at water, perhaps a subtle indication of the immersion to come.

Flowers and cups

The practice of ritually submerging or destroying images is not limited to depictions of gods, goddesses, or demons, but even applies to the floral garlands that adorn many sacred images. The practice of alankara or adorning a murti includes dressing the deity in strands of marigolds, roses, and jasmine flowers. Floral offerings are also used in worship at other religious sites in India including Sufi shrines, Sikh temples, and Christian churches. These flowers are most often tossed into water after their use in religious rites. Once blessed by the divine these floral offerings need to be disposed of in the holiest way possible, either scattered in a sacred river like the Ganga or immersed in a local body of water.

With increased scrutiny over environmental repercussions of such ritual practices, entrepreneurs and designers have begun to collect these discarded flowers and upcycle them into new products. Textile artist Rupa Trivedi and her team at Adiv Pure Nature have created a way to reuse flowers discarded by the Siddhivinayak Hindu temple and the Haji Ali Sufi shrine in Mumbai to create contact-dyed garments and home textiles. In these textiles the temporary floral offerings are made more permanent by imprinting their natural pigments onto cotton and silk fibers. By using water throughout the mordanting and dyeing process, Trivedi maintains the sacred connection to water that is so pivotal to ritual immersion. While Trivedi’s textiles give new life to floral offerings that would otherwise decompose into the earth, it is striking that textiles as a medium epitomize intangibility and impermanence: textiles are objects that break apart through wear and tear, fade under excessive exposure to sunlight, and deteriorate when subjected to bacteria, fungus, or invasive insects.

Perhaps the most pervasive example of the regular destruction of impermanent, temporary objects occurs through the culture of food. Ceramic artists all over South Asia produce small vessels from low-fired terracotta to be used for drinking spiced tea known as masala chai or yoghurt beverages known as lassis which are sold at roadside stands and eateries. While many vendors of chai and lassi have taken to glass, paper, plastic, and styrofoam substitutes, there are still some who prefer to use traditional clay cups. The potters who make these hand-thrown vessels do so with the knowledge that these objects will have short lives: they will be thrown to the ground or crushed underfoot after the chai or lassi has been drunk.

Much of the value of these objects lies in their impermanence and the easy way they return to the earth. While some chai or lassi cups may enter into museum collections—quintessential repositories of permanent objects—their most potent cultural value and circulation is in their temporary use and ultimate demise. As such these vessels remind us that not all tangible cultural heritage is in need of preservation, and sometimes a community requires, even celebrates, the destruction of cultural objects.

Notes:

- For an expanded discussion of colonial valuation of “fine arts” vs. “craft” within the context of unfired clay sculpture see Susan Bean, “The Unfired Clay Sculpture of Bengal in the Artscape of Modern South Asia,” in Rebecca M. Brown and Deborah S. Hutton, eds., A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture (West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2011), 604–628.

- Ganesha Chaturthi occurs every year on the day of Ananta Caturdasi in the month of Bhadrapada (according to the Chandramana calendar).

- For more on the sacred nature of the Ganga and its connection to other bodies of water in India, see Diana Eck, India: A Sacred Geography (New York: Random House, 2012), 131–188.

- Clay has been a material of ritual importance on the subcontinent for millennia. See Bean, “The Unfired Clay Sculpture of Bengal,” 609.

- For further discussion of the environmental implications of ritual immersion of synthetic Ganesha images see Dinesh C. Sharma, “Idol immersion poses water pollution threat” in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (October 2014, Vol. 12, No. 8): 431; and M. Vikram Reddy and A. Vijay Kumar, “Effects of Ganesh-idol immersion on some water quality parameters of Hussainsagar Lake” in Current Science, Vol. 81, No. 11 (10 December 2001): 1412–1413.

- There are comparable ornamental patterns made on the walls of homes. See for example, Asimakrishna Dasa, Evening Blossoms: The Temple Tradition of Sanjhi in Vrndavana (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 1996).

- See for example, Stella Kramrisch, “The Art Ritual of Women,” in Unknown India (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1968); and Pupul Jayakar, The Earthen Drum: An Introduction to the Ritual Arts of Rural India (New Delhi: National Museum, 1980).

- Tibetan Buddhist monks are famous for creating similar temporary paintings in the form of sand mandalas. For example, see monks creating a mandala at the Rubin Museum.

- For more on the Ramlila of Ramnagar, see Richard Schechner and Linda Hess, “The Ramlila of Ramnagar” in The Drama Review: TDR, September 1977, Vol. 21, No. 3, Annual Performance Issue (September 1977): 51–82; and “Ramnagar Ramlila: All about the 200-yr-old cultural extravaganza.”

- For more on Durga Puja pandals and their makers see Bean, “The Unfired Clay Sculpture of Bengal in the Artscape of Modern South Asia,” 604–628; Tapati Guha-Thakurta, “From Spectacle to ‘Art’” in ArtIndia Vol 9, Issue 3 (Quarter 3, 2004): 34–56; Krishna Dutta, Image-Makers of Kumortuli and the Durga Puja Festival. New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2016; and Geir Heirestad, “The Durga Puja Business,” in Caste, Entrepreneurship and the Illusions of Tradition: Branding the Potters of Kolkata (Anthem Press, 2017), 1–6.

Beliefs made visible: Buddhist art in South Asia

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Video from the Asian Art Museum.

Beliefs made visible: Hindu art in South Asia

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Video from the Asian Art Museum.

Discovering Sacred Texts: Hinduism

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Additional resources:

Three Hindu gods

The Hindu preserver

Vishnu is one of the most popular gods of the Hindu pantheon. His portrayal here is standard: a royal figure standing tall, crowned and bejeweled, in keeping with his role as king and preserver of order within the universe. He carries a gada (mace) and chakra (disc) in his hands. The other two hands, which would have held a lotus and conch, are broken. On his forehead he wears a vertical mark or tilak, commonly worn by followers of Vishnu. In keeping with his iconography as the divine king, he is heavily bejeweled, wears a sacred thread that runs over his left shoulder and a long garland that comes down to his knees.

He stands flanked by two attendants, who may be his consorts Bhu and Shri, on a double lotus. The stele has a triangular top unlike earlier examples which were usually in the shape of a gently lobed arch. On either side of his crown are celestial garland bearers and musicians, the Vidyadharas and Kinnaras. A kirtimukha, or auspicious face of glory, is carved on the top centre of the arch.

The sculpture is typical of workmanship of the Pala dynasty of twelfth-century Bengal. The heart-shaped face with stylized arched eyebrows, long eyes that are slightly upturned at the ends, the broad nose, and the pursed smile are all characteristic.

A temple image of the Divine Couple: Shiva and Parvati

Shiva is a powerful Hindu deity. He has a female consort, like most of the gods, one of whose names is Parvati, “the daughter of the mountain.” Shiva and Parvati may appear as a loving couple sitting together in a form called Umamaheshvara. In this example two separate bronze images have been designed as a group. Both Shiva and Parvati wear elaborate jewelry. Shiva is the more powerful deity and so he is depicted with four arms and is the taller figure. In his hands he holds his weapon, the trident, a small deer and a fruit. His fourth hand is raised in reassurance (abhayamudra). Like other images of Shiva he wears two different earrings. Parvati holds a lotus in one hand and a round fruit in the other.

Bronze-casting in the eleventh century was highly developed in Tamil Nadu in the far south of India. However, these two bronzes are unusually large for the Deccan in the same period.

The erect frontal pose of these two figures contrasts with the relaxed, naturalistic posture of many images from Tamil Nadu of the Chola period.

The Hindu creator god

It is often said that there is a trinity of Hindu gods: Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver and Shiva the destroyer. But while Vishnu and Shiva have followers and temples all over India, Brahma is not worshiped as a major deity. Brahma is the personified form of an indefinable and unknowable divine principle called by Hindus brahman. In the myth of Shiva as Lingodbhava, when Brahma searches for the top of the linga of fire, Brahma falsely claimed that he had found flowers on its summit, when in fact the Shiva linga was without end. For this lie he was punished by having no devotees. There are very few temples dedicated to Brahma alone in India. The only one of renown is at Pushkar, in Rajasthan.

Brahma can be recognized by his four heads, only three of which are visible in this sculpture. In two of his four hands he holds a water pot and a rosary. Brahma originally had five heads but Shiva, in a fit of rage, cut one off. Shiva as Bhairava is depicted as a wandering ascetic with Brahma’s fifth head stuck to his hand as a reminder of his crime. Brahma is commonly placed in a niche on the north side of Shaiva temples in Tamil Nadu together with sculptures of Dakshinamurti and Lingodbhava.

Suggested readings:

T. R. Blurton, Hindu art (London, The British Museum Press, 1992).

© Trustees of the British Museum

Ganesha Jayanti, Lord of Beginnings

The remover of obstacles

The elephant-headed Ganesha is renowned throughout India as the Lord of Beginnings, and both the placer and the remover of obstacles. It is for this reason that he is worshipped before any new venture is begun, when his benediction is essential. Temporary statues are created every year for the Ganeshchaturthi festival in Mumbai, and are placed in public or domestic shrines before being immersed in water at the end of the celebrations.

February 3, 2014 was the Hindu festival of Ganesha Jayanti, Ganesha’s birthday. The main annual Ganesha festival, Ganeshchaturthi, is celebrated from August to September, but this is another significant time for worshipers of Ganesha.

Different traditions celebrate Ganesha Jayanti (Ganesha’s birthday) on different days. It is usually observed in the month of Magha (January to February) on the fourth day of Shukla paksha, the bright fortnight or waxing moon in the Hindu calendar, particularly in the Indian states of Maharashtra and Karnataka. The celebrations of Ganesha Jayanti in the month of Magha are simple, with devotees observing a fast. Before worship, devotees take a bath of water mixed with til (sesame seeds) after smearing a paste of the same substance on their body.

Domestic shrines and temples are decorated for the occasion. Special offerings are made to the permanent Ganesha images which are worshipped daily. In some places Ganesha is symbolically worshipped in the form of a cone made of turmeric or cow dung. Food offerings of ladoos (sweet balls) made of til and jaggery (sugar) are offered with great devotion. In some households and temples small images of Ganesha are placed in cradles and worshipped.

The practical reason for making offerings prepared of til and jaggery or applying sesame paste to the body is that when this festival is celebrated it is mid-winter and the body requires high energy supplements. The devotees consider their beloved Ganesha as human and offer preparations of sesame and sugar to provide energy and keep the body warm.

The Ganesha Jayanti festival (Magha shukla Chaturthi) is publicly celebrated in a relatively small number of places, where specially created clay images of Ganesha are worshipped and immersed in the sea or river after 11 or 21 days. During this month the devotees go on a pilgrimage to one of the many Ganesha temples across India. In Maharashtra there are eight places which are particularly sacred to Ganesha, known as Ashtavinaykas (Ashta means eight and Vinayaka is one of the many names of Ganesha) and the pilgrimage is known as Ashtavinayaka yatra. These are at Morgaon, Theur, Lenyadri, Ozar, Ranjangaon, Siddhatek, Pali and Mahad.

Manisha Nene, Assistant Director, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS)

Suggested readings:

P.B. Courtright, Ganesa: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings (Oxford, 1985).

P. Mitter, Much Maligned Monsters: A history of European reactions to Indian Art (University of Chicago Press, 1992).

R.L. Brown, Ganesha: Studies of an Asian God (Albany, 1991).

P. Pal, Ganesh the benevolent (Bombay, Marg, 1995).

© Trustees of the British Museum

The making and worship of Ganesha statues in Maharashtra

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): The elephant-headed Ganesha is one of the most popular Hindu gods — the creator and remover of obstacles. The main stone sculpture in the display was carved from schist around 800 years ago and was originally positioned on the outside of a temple in the eastern state of Orissa (recently renamed Odisha). The display brings this sculpture together with other more recent depictions of Ganesha created for different purposes. Among these are the temporary statues created every year for the Ganeshchaturthi festival in Mumbai, which are placed in public or domestic shrines before being immersed in water at the end of the celebrations. © Trustees of the British Museum. Created by British Museum.

Introduction to Islam

by DR. ELIZABETH MACAULAY-LEWIS

Origins and the life of Muhammad the Prophet

Islam, Judaism and Christianity are three of the world’s great monotheistic faiths. They share many of the same holy sites, such as Jerusalem, and prophets, such as Abraham. Collectively, scholars refer to these three religions as the Abrahamic faiths, since Abraham and his family played vital roles in the formation of these religions.

Islam was founded by Muhammad (c. 570-632 C.E.), a merchant from the city of Mecca, now in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Mecca was a well-established trading city. The Kaaba (in Mecca) is the focus of pilgrimage for Muslims.

The Qur’an, the holy book of Islam, provides very little detail about Muhammad’s life; however, the hadiths, or sayings of the Prophet, which were largely compiled in the centuries following Muhammad’s death, provide a larger narrative for the events in his life. Muhammad was born in 570 C.E. in Mecca, and his early life was unremarkable. He married a wealthy widow named Khadija. Around 610 C.E., Muhammad had his first religious experience, where he was instructed to recite by the Angel Gabriel. After a period of introspection and self-doubt, Muhammad accepted his role as God’s prophet and began to preach word of the one God, or Allah in Arabic. His first convert was his wife.

Muhammad’s divine recitations form the Qur’an; unlike the Bible or Hindu epics, it is organized into verses, known as ayat. During one of his many visions, in 621 C.E., Muhammad was taken on the famous Night Journey by the Angel Gabriel, travelling from Mecca to the farthest mosque in Jerusalem, from where he ascended into heaven. The site of his ascension is believed to be the stone around which the Dome of the Rock was built. Eventually in 622, Muhammad and his followers fled Mecca for the city of Yathrib, which is known as Medina today, where his community was welcomed. This event is known as the hijra, or emigration. 622, the year of the hijra (A.H.), marks the beginning of the Muslim calendar, which is still in use today.

Between 625-630 C.E., there were a series of battles fought between the Meccans and Muhammad and the new Muslim community. Eventually, Muhammad was victorious and reentered Mecca in 630.

One of Muhammad’s first actions was to purge the Kaaba of all of its idols (before this, the Kaaba was a major site of pilgrimage for the polytheistic religious traditions of the Arabian Peninsula and contained numerous idols of pagan gods). The Kaaba is believed to have been built by Abraham (or Ibrahim as he is known in Arabic) and his son, Ishmael. The Arabs claim descent from Ishmael, the son of Abraham and Hagar. The Kaaba then became the most important center for pilgrimage in Islam.

In 632, Muhammad died in Medina. Muslims believe that he was the final in a line of prophets, which included Moses, Abraham, and Jesus.

After Muhammad’s death

The century following Muhammad’s death was dominated by military conquest and expansion. Muhammad was succeeded by the four “rightly-guided” Caliphs (khalifa or successor in Arabic): Abu Bakr (632-34 C.E.), Umar (634-44 C.E.), Uthman (644-56 C.E.), and Ali (656-661 C.E.). The Qur’an is believed to have been codified during Uthman’s reign. The final caliph, Ali, was married to Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter and was murdered in 661. The death of Ali is a very important event; his followers, who believed that he should have succeeded Muhammad directly, became known as the Shi’a, meaning the followers of Ali. Today, the Shi’ite community is composed of several different branches, and there are large Shi’a populations in Iran, Iraq, and Bahrain. The Sunnis, who do not hold that Ali should have directly succeeded Muhammad, compose the largest branch of Islam; their adherents can be found across North Africa, the Middle East, as well as in Asia and Europe.

During the seventh and early eighth centuries, the Arab armies conquered large swaths of territory in the Middle East, North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and Central Asia, despite on-going civil wars in Arabia and the Middle East. Eventually, the Umayyad Dynasty emerged as the rulers, with Abd al-Malik completing the Dome of the Rock, one of the earliest surviving Islamic monuments, in 691/2 C.E. The Umayyads reigned until 749/50 C.E., when they were overthrown, and the Abbasid Dynasty assumed the Caliphate and ruled large sections of the Islamic world. However, with the Abbasid Revolution, no one ruler would ever again control all of the Islamic lands.

Additional resources:

The Birth of Islam on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

World Religions in Art: Islam (from the Minneapolis Museum of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Indus Valley Civilization

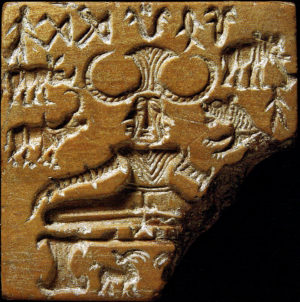

An Indus Seal

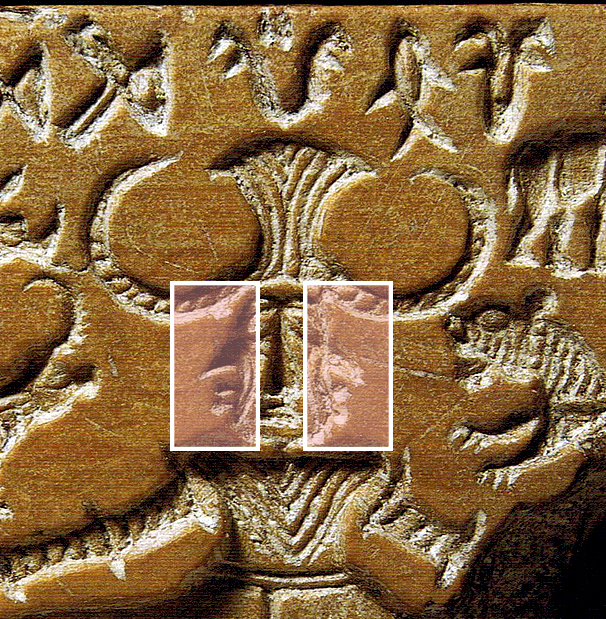

Incised on this small stone (less than two inches across), we see a large figure seated on a dais surrounded by a horned buffalo, a rhinoceros, an elephant, and a tiger. Beneath the platform is a small antlered deer that is one of a pair. Although the deer on the right has broken off at some point, enough of its antler remains to determine that the deer has its head turned away from the center and, like its partner, was looking out towards the edge of the seat. An inscription (as yet untranslated), has been carved into the very top of the seal, with one symbol apparently displaced to the space between the elephant and the tiger. The stone seal, which would have been pressed onto a soft base such as clay to create a positive imprint, is dated to c. 2500–2400 B.C.E. and was found in the archaeological site of Mohenjo-daro, in what is now Sindh, Pakistan.

Imprints of an ancient civilization

Mohenjo-daro was one in a series of settlements that is collectively known as the Indus Valley Civilization. Named after the Indus River, this early civilization encompassed a vast swath of present-day Pakistan and northwestern India. Mohenjo-daro had an estimated 40,000 residents and was a well-planned settlement with efficient urban facilities that included street drainage, a sewage system, and large civic buildings. Residents also had access to well-water and many had baths in their homes.

Seals numbering in the thousands have been discovered in excavations of Indus cities as well as in sites in the Persian Gulf in southwest Asia. Seals from the Gulf region have similarly been found in Indus cities. The finds suggest active trade and exchange between these areas in the third millennium B.C.E.

Seals often feature a single, large animal such as buffaloes, rhinoceroses, and elephants. The animals are always shown in profile and sometimes standing alongside feeding troughs. Unicorns (that is, animals with a single horn), are also seen on Indus seals, as are trees and animals with a single body and multiple heads. On the rear of the seals is a single and centered rounded projection (see above) with a bored hole with which the seal could be strung.

Reading Indus seals

The seals include inscriptions in the form of pictograms that unfortunately we cannot yet read; the Indus Valley script is yet to be deciphered. Scholarship has been able to determine, however, that most seals were likely important components of trade. Clay sealings (the positive imprints of the seals) have revealed traces of rope that suggest that they may have been used to brand fastened bundles of merchandise. It has also been theorized that the inscriptions on the seals indicate ownership and that the animals are emblems that referenced particular persons and merchant guilds.

Lord of the beasts

The figure’s frontality and symmetry demands deference, as does its impressively large and deeply curved horned headdress. The face is long, with a prominent nose, deeply set eyes, and a closed mouth. The figure wears what looks like several necklaces over the chest as well as bangles and bracelets along the length of the arms. There appears to also be a belt at the waist with a tassel, but it is unclear what, if anything, is worn below the waist. The legs are elongated and, even folded at the knee, occupy the length of the seat. The right arm falls gracefully towards the knee, but does not touch it. Based on other examples of this general type of seated figure, we can imagine that the left hand was similarly positioned.

The figure has been described by scholars variously as male, female, with multiple heads, and not. It is also most frequently described as the Pashupati seal, after an epithet for the Hindu god Shiva that means “lord of beasts.” The figure’s apparent mastery over wild animals is thought to be implied by the type of animals — that is, the buffalo, rhinoceros, elephant, and the tiger — included in the seal.

The pair of relatively smaller stylized deer below the figure appear to be different in conception from the other animals. But questions remain: Is this a narrative scene that shows deer gathered at a site? Or are the deer meant to be understood as designs on the dais? The other animals, in contrast, are far more prominent and their importance to the seal’s messaging is evident. They are powerful animals and as if to emphasize this point further the tiger is shown rearing, with its mouth open (while the seated figure appears unfazed).

An early form of Shiva?

Early scholarship [1] posited that the figure in the seal was an ancient Vedic form (named Rudra) of the Hindu god Shiva. This theory was based in part on the following:

- The animals in the seal imply the figure’s dominion over animals and that an epithet of Rudra – Pashupati, the lord of animals – is similarly an epithet of Shiva.

- The figure is seated in a yogic pose (in particular with heels together) and an aspect of Shiva is known as Yogisvara – the supreme yogi (practitioner of yoga).

- A supposition that the figure has three faces as opposed to just one and Shiva is sometimes represented in sacred art with three or more faces.

The substantial chronological gap between the date of the seal (third millennium B.C.E.) and the date of the Vedas (second millennium B.C.E.) should also be noted, although this does not necessarily preclude the inclusion of older traditions in the sacred Vedic texts. There are other major points to be considered, however, that complicate an identification of the figure as a type of proto-Shiva.

- The link between the seal’s iconography and the Vedic themes that have been used to support the Pashupati and Rudra-Shiva thesis are indeterminate. [2]

- Yoga was likely known and practiced for centuries before it was codified into a series of prescribed mental and physical exercises in the second century B.C.E., but it is unclear if the figure in the seal is in fact an early representation of the practice of yoga.

- The presence of lateral faces on the figure is not accepted by all scholars; it is uncertain if the sharp protuberances on either side of the figure’s head indicate facial features. In addition, representations of Shiva with three or more faces have so far only been dated to the much later (medieval) period; see the multiple faces of Shiva as Sadashiva carved in the sixth century here, for example.

Iconographic symbolism

It is evident from the figure’s controlled and meditative bearing that we are witnessing a type of principled self-discipline and asceticism that calls for reverence. Taken with the careful design of the seal — in particular, the primary place of importance given to the main figure, their throne-like dais, regal adornment and frontal pose, and the subsidiary positioning of powerful animals — it is clear, that the seal would have held great symbolic and reverential import for its owner.

Although our inability to read the inscription on the seal undermines our understanding of the intended purpose and meaning of the seal, its iconography bring us a step closer to understanding the people of the Indus Valley Civilization and their rich spiritual culture.

Notes:

[1] See “Male god, the proto-type of the historic Shiva,” in Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, vol 1, edited by John Marshall (London: Arthur Probstain, 1931), pp. 52–56.

[2] See Doris Srinivasan, “The So-Called Proto-Siva Seal from Mohenjo-Daro: An Iconological Assessment, Archives of Asian Art 29 (1975/1976), pp. 47–58. Based on a study of pre-Indus and Indus period material culture, Srinivasan has forwarded the alternate possibility that the figure represented on the seal may be a “divine bull-man” and that the inclusion of the animals on the seal is indicative of an invocation for a successful hunt. Srinivasan, ibid., p.57.

Additional resources:

Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon Press, 1997).

John Marshall, ed., Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, vol 1, edited by John Marshall (London: Arthur Probstain, 1931).

Romila Thapar, Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997).

Doris Srinivasan, “The So-Called Proto-Siva Seal from Mohenjo-Daro: An Iconological Assessment, Archives of Asian Art 29 (1975/1976), pp. 47–58.

More on the Indus Valley Civilization

Pasupati seal at the National Museum, New Delhi

Art of the Magadha dynasties

The powers that arose in the Magadha region influenced India for centuries afterward.

4th century B.C.E. – 7th century C.E.

The Pillars of Ashoka

A Buddhist king

What happens when a powerful ruler adopts a new religion that contradicts the life into which he was born? What about when this change occurs during the height of his rule when things are pretty much going his way? How is that information conveyed over a large geographical region with thousands of inhabitants?

King Ashoka, who many believe was an early convert to Buddhism, decided to solve these problems by erecting pillars that rose some 50 feet into the sky. The pillars were raised throughout the Magadha region in the North of India that had emerged as the center of the first Indian empire, the Mauryan Dynasty (322-185 B.C.E). Written on these pillars, intertwined in the message of Buddhist compassion, were the merits of King Ashoka.

The third emperor of the Mauryan dynasty, Ashoka (pronounced Ashoke), who ruled from c. 279 B.C.E. – 232 B.C.E., was the first leader to accept Buddhism and thus the first major patron of Buddhist art.[1] Ashoka made a dramatic conversion to Buddhism after witnessing the carnage that resulted from his conquest of the village of Kalinga. He adopted the teachings of the Buddha known as the Four Noble Truths, referred to as the dharma (the law):

Life is suffering (suffering=rebirth)

the cause of suffering is desire

the cause of desire must be overcome

when desire is overcome, there is no more suffering (suffering=rebirth)

Individuals who come to fully understand the Four Noble Truths are able to achieve Enlightenment, ending samsara, the endless cycle of birth and rebirth. Ashoka also pledged to follow the Six Cardinal Perfections (the Paramitas), which were codes of conduct created after the Buddha’s death providing instructions for the Buddhist practitioners to follow a compassionate Buddhist practice. Ashoka did not require that everyone in his kingdom become Buddhist, and Buddhism did not become the state religion, but through Ashoka’s support, it spread widely and rapidly.

The pillars

One of Ashoka’s first artistic programs was to erect the pillars that are now scattered throughout what was the Mauryan empire. The pillars vary from 40 to 50 feet in height. They are cut from two different types of stone—one for the shaft and another for the capital. The shaft was almost always cut from a single piece of stone. Laborers cut and dragged the stone from quarries in Mathura and Chunar, located in the northern part of India within Ashoka’s empire. The pillars weigh about 50 tons each. Only 19 of the original pillars survive and many are in fragments. The first pillar was discovered in the sixteenth century.

Lotus and lion

The physical appearance of the pillars underscores the Buddhist doctrine. Most of the pillars were topped by sculptures of animals. Each pillar is also topped by an inverted lotus flower, which is the most pervasive symbol of Buddhism (a lotus flower rises from the muddy water to bloom unblemished on the surface—thus the lotus became an analogy for the Buddhist practitioner as he or she, living with the challenges of everyday life and the endless cycle of birth and rebirth, was able to achieve Enlightenment, or the knowledge of how to be released from samsara, through following the Four Noble Truths). This flower, and the animal that surmount it, form the capital, the topmost part of a column. Most pillars are topped with a single lion or a bull in either seated or standing positions. The Buddha was born into the Shakya or lion clan. The lion, in many cultures, also indicates royalty or leadership. The animals are always in the round and carved from a single piece of stone.

The edicts

Some pillars had edicts (proclamations) inscribed upon them. The edicts were translated in the 1830s. Since the seventeenth century, 150 Ashokan edicts have been found carved into the face of rocks and cave walls as well as the pillars, all of which served to mark his kingdom, which stretched across northern India and south to below the central Deccan plateau and in areas now known as Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. The rocks and pillars were placed along trade routes and in border cities where the edicts would be read by the largest number of people possible. They were also erected at pilgrimage sites such as at Bodh Gaya, the place of Buddha’s Enlightenment, and Sarnath, the site of his First Sermon and Sanchi, where the Mahastupa, the Great Stupa of Sanchi, is located (a stupa is a burial mound for an esteemed person. When the Buddha died, he was cremated and his ashes were divided and buried in several stupas. These stupas became pilgrimage sites for Buddhist practitioners).

Some pillars were also inscribed with dedicatory inscriptions, which firmly date them and name Ashoka as the patron. The script was Brahmi, the language from which all Indic language developed. A few of the edicts found in the western part of India are written in a script that is closely related to Sanskrit and a pillar in Afghanistan is inscribed in both Aramaic and Greek—demonstrating Ashoka’s desire to reach the many cultures of his kingdom. Some of the inscriptions are secular in nature. Ashoka apologizes for the massacre in Kalinga and assures the people that he now only has their welfare in mind. Some boast of the good works that Ashoka has done, underscoring his desire to provide for his people.

The Hinayana period

The pillars (and the stupas) were created in the Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle) period. Hinayana is the first stage of Buddhism, roughly dated from the sixth c. to the first century B.C.E., in which no images of the Buddha were made. The memory of the historical Buddha and his teachings was enough to sustain the practitioners. But several symbols became popular as stand-ins for the human likeness of the Buddha. The lotus, as noted above, is one. The lion, which is typically seen on the Ashokan pillars, is another. The wheel (cakra) is a symbol of both samsara, the endless circle of birth and rebirth, and the dharma, the Four Noble Truths.

Why a pillar?

There are a few hypotheses about why Ashoka used the pillar as a means for communicating his Buddhist message. It is quite possible that Persian artists came to Ashoka’s empire in search of work, bringing with them the form of the pillar, which was common in Persian art. But it is also likely that Ashoka chose the pillar because it was already an established Indian art form. In both Buddhism and Hinduism, the pillar symbolized the axis mundi (the axis on which the world spins).

The pillars and edicts represent the first physical evidence of the Buddhist faith. The inscriptions assert Ashoka’s Buddhism and support his desire to spread the dharma throughout his kingdom. The edicts say nothing about the philosophical aspects of Buddhism and scholars have suggested that this demonstrates that Ashoka had a very simple and naïve understanding of the dharma. But, as Ven S. Dhammika suggests, Ashoka’s goal was not to expound on the truths of Buddhism, but to inform the people of his reforms and encourage them to live a moral life. The edicts, through their strategic placement and couched in the Buddhist dharma, serve to underscore Ashoka’s administrative role as a tolerant leader.

Edict #6 is a good example:

Beloved of the Gods speaks thus: Twelve years after my coronation

I started to have Dhamma edicts written for the welfare and happiness of the people, and so that not transgressing them they might grow in the Dhamma. Thinking: “How can the welfare and happiness of the people be secured?” I give my attention to my relatives, to those dwelling far, so I can lead them to happiness and then I act accordingly. I do the same for all groups. I have honored all religions with various honors. But I consider it best to meet with people personally.

[1] The details and extent to which Emperor Ashoka was a practicing Buddhist is a topic debated by scholars, though it is widely accepted that he was the first major patron of Buddhist art on the Indian subcontinent. For more discussions as to whether or not Ashoka was a “secular” ruler, see Akeel Bilgrami, ed.,Beyond the Secular West (Columbia University Press, 2016); Charles Taylor and Alfred Stepan, eds., Boundaries of Toleration: Religion, Culture, and Public Life (Columbia University Press, 2014); and Ashis Nandy, “The Politics of Secularism and the Recovery of Religious Tolerance,” Alternatives XIII (1988), pp. 177-194. For more on Ashoka’s relationship with the Buddhist community and doctrine, see Alf Hiltebeitel, “King Asoka’s Dhamma,” in Dharma (University of Hawai’i Press, 2010), pp. 12-18 and John S. Strong, The Legend of King Asoka: A Study and Translation of the Asokavadana (Princeton University Press, 1983).

Lion Capital, Ashokan Pillar at Sarnath

Site of Buddha’s First Sermon

The most celebrated of the Ashokan pillars is the one erected at Sarnath, the site of Buddha’s First Sermon where he shared the Four Noble Truths (the dharma or the law). Currently, the pillar remains where it was originally sunk into the ground, but the capital is now on display at the Sarnath Museum. It is this pillar that was adopted as the national emblem of India. It is depicted on the one rupee note and the two rupee coin.

The Pillar

The pillar is a symbol of the axis mundi (cosmic axis) and of the column that rises everyday at noon from the legendary Lake Anavatapta (the lake at the center of the universe according to Buddhist cosmology) to touch the sun.

The Capital

The top of the column—the capital—has three parts. First, a base of a lotus flower, the most ubiquitous symbol of Buddhism.

Then, a drum on which four animals are carved representing the four cardinal directions: a horse (west), an ox (east), an elephant (south), and a lion (north). They also represent the four rivers that leave Lake Anavatapta and enter the world as the four major rivers. Each of the animals can also be identified by each of the four perils of samsara. The moving animals follow one another endlessly turning the wheel of existence.

Four lions stand atop the drum, each facing in the four cardinal directions. Their mouths are open roaring or spreading the dharma, the Four Noble Truths, across the land. The lion references the Buddha, formerly Shakyamuni, a member of the Shakya (lion) clan. The lion is also a symbol of royalty and leadership and may also represent the Buddhist king Ashoka who ordered these columns. A cakra (wheel) was originally mounted above the lions.

Some of the lion capitals that survive have a row of geese carved below the lions. The goose is an ancient Vedic symbol (Veda means knowledge in Sanskrit and the Vedas refers to the canonical collection of hymns, prayers and liturgical formulas that make up the earliest of the Hindu sacred writings. Many of the Buddhist symbols and practices derive from these early texts). The flight of the goose is thought of as a link between the earthly and heavenly spheres.

The pillar reads from bottom to top. The lotus represents the murky water of the mundane world and the four animals remind the practitioner of the unending cycle of samsara as we remain, through our ignorance and fear, stuck in the material world. But the cakras between them offer the promise of the Eightfold Path, that guide one to the unmoving center at the hub of the wheel. Note that in these particular cakras, the number of spokes in the wheel (eight for the Eightfold Path), had not yet been standardized.

The lions are the Buddha himself from whom the knowledge of release from samsara is possible. And the cakra that once stood at the apex represents moksa, the release from samsara. The symbolism of moving up the column toward Enlightenment parallels the way in which the practitioner meditates on the stupa in order to attain the same goal.

Additional Resources:

This sculpture at the Archaeological Museum Sarnath

Lion Capital of Asoka Wikipedia entry

The Great Stupa at Sanchi

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Video from the Asian Art Museum

Can a mound of dirt represent the Buddha, the path to Enlightenment, a mountain and the universe all at the same time? It can if its a stupa. The stupa (“stupa” is Sanskrit for heap) is an important form of Buddhist architecture, though it predates Buddhism. It is generally considered to be a sepulchral monument—a place of burial or a receptacle for religious objects. At its simplest, a stupa is a dirt burial mound faced with stone. In Buddhism, the earliest stupas contained portions of the Buddha’s ashes, and as a result, the stupa began to be associated with the body of the Buddha. Adding the Buddha’s ashes to the mound of dirt activated it with the energy of the Buddha himself.

Early stupas

Before Buddhism, great teachers were buried in mounds. Some were cremated, but sometimes they were buried in a seated, meditative position. The mound of earth covered them up. Thus, the domed shape of the stupa came to represent a person seated in meditation much as the Buddha was when he achieved Enlightenment and knowledge of the Four Noble Truths. The base of the stupa represents his crossed legs as he sat in a meditative pose (called padmasana or the lotus position). The middle portion is the Buddha’s body and the top of the mound, where a pole rises from the apex surrounded by a small fence, represents his head. Before images of the human Buddha were created, reliefs often depicted practitioners demonstrating devotion to a stupa.

The ashes of the Buddha were buried in stupas built at locations associated with important events in the Buddha’s life including Lumbini (where he was born), Bodh Gaya (where he achieved Enlightenment), Deer Park at Sarnath (where he preached his first sermon sharing the Four Noble Truths (also called the dharma or the law), and Kushingara (where he died). The choice of these sites and others were based on both real and legendary events.

“Calm and glad”

According to legend, King Ashoka, who was the first king to embrace Buddhism (he ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent from c. 269 – 232 B.C.E.), created 84,000 stupas and divided the Buddha’s ashes among them all. While this is an exaggeration (and the stupas were built by Ashoka some 250 years after the Buddha’s death), it is clear that Ashoka was responsible for building many stupas all over northern India and the other territories under the Mauryan Dynasty in areas now known as Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.