13.4.5: North Africa

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 88692

North Africa

Prehistoric rock art, ancient Egypt, and the art of Islam.

12,000 B.C.E. - 900 C.E.

About North Africa

by SMARTHISTORY

North Africa includes Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, and the Canary and Madeira Islands.

Algeria and Libya

The art of Algeria

Algeria is home to some of the world's most significant ancient rock art.

12,000 - 2,000 B.C.E.

Rock Art in North Africa

Forests of Stone

Algeria is Africa’s largest country and most of it falls within the Sahara Desert. It also hosts a rich rock art concentration. Most of the sites are found in the south east of the country near its borders with Libya and Niger but there are also important concentrations in the Algerian Maghreb and in the Hoggar Mountains in the central south.

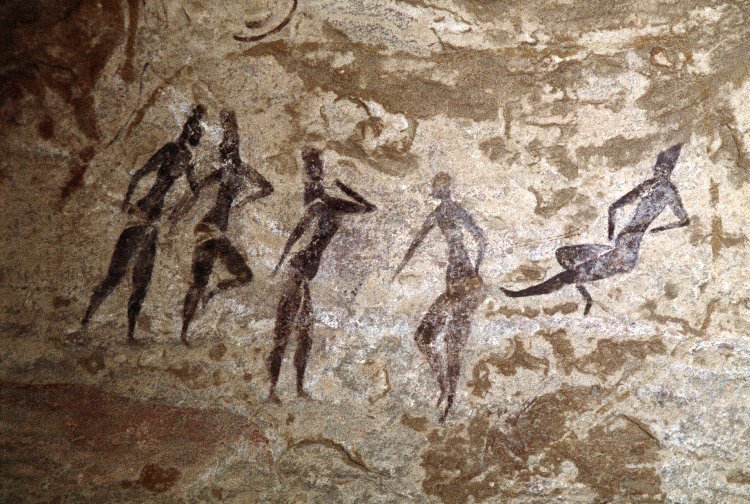

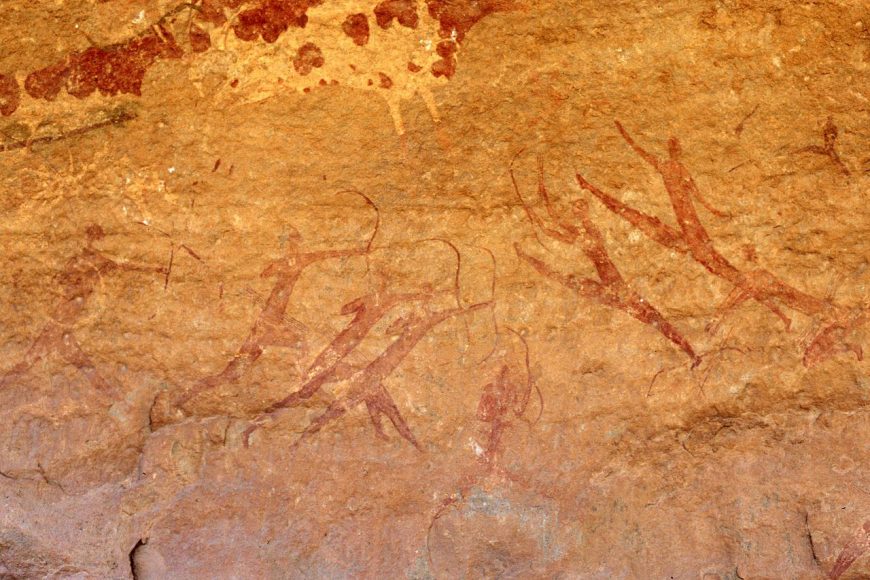

The most renowned of all these areas is the Tassili n’Ajjer (meaning “plateau of chasms”) in the south east. Water and sand erosion have carved out a landscape of thin passageways, large arches, and high-pillared rocks, described as “forests of stone” by French archaeologist and ethnographer Henri Lhote. The resulting undercuts at cliff bases have created rock shelters with smooth walls ideal for painting and engraving (left).

The Ajjer plateau rises to approximately 500-600 meters above the plain of Djanet, an oasis city, and capital of Djanet District, in Illizi Province, southeast Algeria. The region has been inhabited since Neolithic times, when the environment was much wetter and sustained a wider extent of flora and fauna as witnessed in the numerous rock paintings of Tassili n’Ajjer. Classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982 and Biosphere Reserve in 1986, Tassili n’Ajjer covers a vast area of desert landscape in southern Algeria, stretching from the Niger and Libyan border area, north and east of Djanet, as far as Illizi and Amguid, covering an area of 72,000 sq. km.

The rock art of the Tassili region was introduced to Western eyes as a result of visits and sketches made by French legionnaires, in particular a Lt. Brenans during the 1930s. On several of his expeditions, Lt. Brenans took French archaeologist Henri Lhote who went on to revisit sites in Algeria between 1956-1970 documenting and recording the images he found. Regrettably, some previous methods of recording and/or documenting have caused damage to the vibrancy and integrity of the images.

Subject matter

More than 15,000 rock paintings and engravings, dating back as far as 12,000 years are located in this region and have made Tassili world famous for this reason. The art depicts herds of cattle and large wild animals such as giraffe and elephant, as well as human activities such as hunting and dancing. The area is especially famous for its Round Head paintings which were first described and published by Henri Lhote in the 1950s. Thought to date from around 9,000 years old, some of these paintings are the largest found on the African continent, measuring up to 13 feet in height.

Although the styles and subjects of north African rock art vary, there are commonalities: images are most often figurative and frequently depict animals, both wild and domestic. There are also many images of human figures, sometimes with accessories such as recognisable weaponry or clothing. These may be painted or engraved, with frequent occurrences of both, at times in the same context. Engravings are generally more common, although this may simply be a preservation bias due to their greater durability.

The physical context of rock art sites varies depending on geographical and topographical factors—for example, Moroccan rock engravings are often found on open rocky outcrops, while Tunisia’s Djebibina rock art sites have all been found in rock shelters. Rock art in the vast and harsh environments of the Sahara is often inaccessible and hard to find, and there is probably a great deal of rock art that is yet to be seen by archaeologists; what is known has mostly been documented within the last century.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Rock Art in the Green Sahara (Africa)

Rock art is one of the best records of the life of past peoples who lived across the Sahara.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Video from The British Museum

The Sahara is the world’s largest hot desert, spanning the entire northern part of Africa. Yet it hasn’t always been dry — archaeological and geological research shows that it has undergone major climatic changes over thousands of years. Rock art often depicts extraordinary images of life, landscape and animals that show a time when the Sahara was much greener and wetter than it is now.

This film is in collaborative partnership with the Leverhulme Trust-funded project: “Peopling the Green Sahara. A multi-proxy approach to reconstructing the ecological and demographic history of the Saharan Holocene”, Paul Breeze, Nick Drake and Katie Manning, Department of Geography, King’s College London Modelling and mapping of the Green Sahara ©Kings College London Images ©Trust for African Rock Art (TARA)/David Coulson & ©Kings College London

Running Horned Woman, Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria

by NATHALIE HAGER

“Discovery”

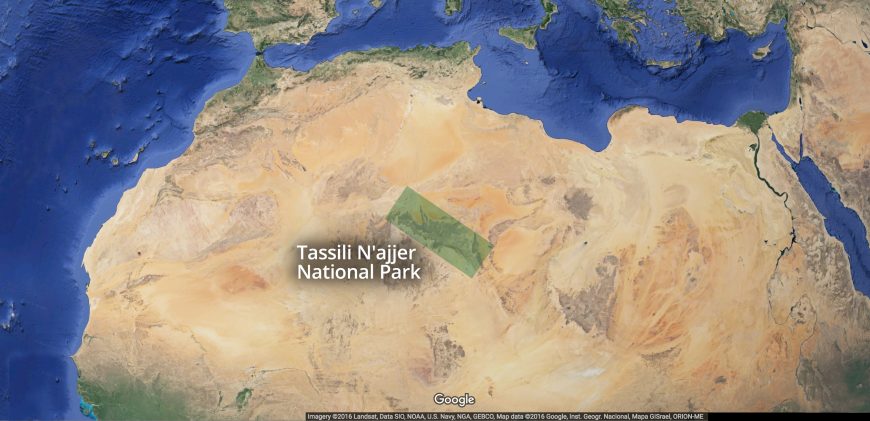

Between 1933 and 1940, camel corps officer Lieutenant Brenans of the French Foreign Legion completed a series of small sketches and hand written notes detailing his discovery of dozens of rock art sites deep within the canyons of the Tassili n’Ajjer. Tassili n’Ajjer is a difficult to access plateau in the Algerian section of the Sahara Desert near the borders of Libya and Niger in northern Africa (see map below). Brenans donated hundreds of his sketches to the Bardo Museum in Algiers, alerting the scientific community to one of the richest rock art concentrations on Earth and prompting site visits that included fellow Frenchman and archaeologist Henri Lhote.

Lhote recognized the importance of the region and returned again and again, most notably in 1956 with a team of copyists for a 16 month expedition to map and study the rock art of the Tassili. Two years later Lhote published A la découverte des fresques du Tassili. The book became an instant best-seller, and today is one of the most popular texts on archaeological discovery.

Lhote made African rock art famous by bringing some of the estimated 15,000 human figure and animal paintings and engravings found on the rock walls of the Tassili’s many gorges and shelters it to the wider public. Yet contrary to the impression left by the title of his book, neither Lhote nor his team could lay claim to having discovered Central Saharan rock art: long before Lhote, and even before Brenans, in the late nineteenth century a number of travelers from Germany, Switzerland, and France had noted the existence of “strange” and “important” rock sculptures in Ghat, Tadrart Acacus, and Upper Tassili. But it was the Tuareg—the indigenous peoples of the region, many of whom served as guides to these early European explorers—who long knew of the paintings and engravings covering the rock faces of the Tassili.

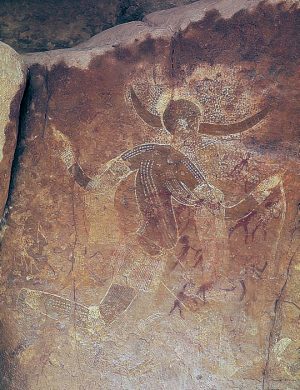

The “Horned Goddess”

Lhote published not only reproductions of the paintings and engravings he found on the rock walls of the Tassili, but also his observations. In one excerpt he reported that with a can of water and a sponge in hand he set out to investigate a “curious figure” spotted by a member of his team in an isolated rock shelter located within a compact group of mountains known as the Aouanrhet massif, the highest of all the “rock cities” on the Tassili. Lhote swabbed the wall with water to reveal a figure he called the “Horned Goddess”:

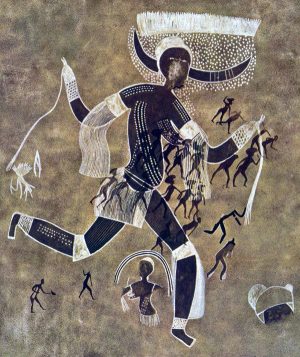

On the damp rock surface stood out the gracious silhouette of a woman running. One of her legs, slightly flexed, just touched the ground, while the other was raised in the air as high as it would normally go. From the knees, the belt and the widely outstretched arms fell fine fringes. From either side of the head and above two horns that spread out horizontally was an extensive dotted area resembling a cloud of grain falling from a wheat field. Although the whole assemblage was skillfully and carefully composed there was something free and easy about it…

The Running Horned Woman, the title by which the painting is commonly known today, was found in a massif so secluded and so difficult to access that Lhote’s team concluded that the collection of shelters was likely a sanctuary and the female figure—“the most beautiful, the most finished and the most original”—a goddess:

Perhaps we have here the figure of a priestess of some agricultural religion or the picture of a goddess of such a cult who foreshadow—or is derived from—the goddess Isis, to whom, in Egypt, was attributed the discovery of agriculture.

Lhote’s suggestion that the painting’s source was Egyptian was influenced by a recently published hypothesis by his mentor, the French anthropologist Henri Breuil, the then undisputed authority on prehistoric rock art who was renowned for his work on Paleolithic cave art in Europe. In an essay titled, “The White Lady of Brandberg, South-West Africa, Her Companions and Her Guards,” Breuil famously claimed that a painting discovered in a small rock shelter in Namibia showed influences of Classical antiquity and was not African in origin, but possibly the work of Phoenician travellers from the Mediterranean. Lhote, equally convinced of outside influence, linked the Tassili painting’s provenance with Breuil’s ideas and revised the title to the ‘White Lady’ of Aouanrhet:

In other paintings found a few days later in the same massif we were able to discern, from some characteristic features, an indication of Egyptian influence. Some features are, no doubt, not very marked in our ‘White Lady’; still, all the same, some details as the curve of the breasts, led us to think that the picture may have been executed at a time when Egyptian traditions were beginning to be felt in the Tassili.

Foreign influence?

Time and scholarship would reveal that the assignment of Egyptian influence on the Running Horned Woman was erroneous, and Lhote the victim of a hoax: French members of his team made “copies” of Egyptionized figures, passing them off as faithful reproductions of authentic Tassili rock wall paintings. These fakes were accepted by Lhote (if indeed he knew nothing of the forgeries), and falsely sustained his belief in the possibility of foreign influence on Central Saharan rock art. Breuil’s theories were likewise discredited: the myth of the “White Lady” was rejected by every archaeologist of repute, and his promotion of foreign influence viewed as racist.

Yet Breuil and Lhote were not alone in finding it hard to believe that ancient Africans discovered how to make art on their own, or to have developed artistic sensibilities. Until quite recently many Europeans maintained that art “spread” or was “taken” into Africa, and, aiming to prove this thesis, anointed many works with Classical sounding names and sought out similarities with early rock art in Europe. Although such vestiges of colonial thinking are today facing a reckoning, cases such as the “White Lady” (both of Namibia and of Tassili) remind us of the perils of imposing cultural values from the outside.

Chronology

While we have yet to learn how, and in what places, the practice of rock art began, no firm evidence has been found to show that African rock art—some ten million images across the continent—was anything other than a spontaneous initiative by early Africans. Scholars have estimated the earliest art to date to 12,000 or more years ago, yet despite the use of both direct and indirect dating techniques very few firm dates exist (“direct dating” uses measurable physical and chemical analysis, such as radiocarbon dating, while “indirect dating” primarily uses associations from the archaeological context). In the north, where rock art tends to be quite diverse, research has focused on providing detailed descriptions of the art and placing works in chronological sequence based on style and content. This ordering approach results in useful classification and dating systems, dividing the Tassili paintings and engravings into periods of concurrent and overlapping traditions (the Running Horned Woman is estimated to date to approximately 6,000 to 4,000 B.C.E.—placing it within the “Round Head Period”), but offers little in the way of interpretation of the painting itself.

Advancing an interpretation of the Running Horned Woman

Who was the Running Horned Woman? Was she indeed a goddess, and her rock shelter some sort of sanctuary? What does the image mean? And why did the artist make it? For so long the search for meaning in rock art was considered inappropriate and unachievable—only recently have scholars endeavored to move beyond the mere description of images and styles, and, using a variety of interdisciplinary methods, make serious attempts to interpret the rock art of the Central Sahara.

Lhote recounted that the Running Horned Woman was found on an isolated rock whose base was hollowed out into a number of small shelters that could not have been used as dwellings. This remote location, coupled with an image of marked pictorial quality—depicting a female with two horns on her head, dots on her body probably representing scarification, and wearing such attributes of the dance as armlets and garters—suggested to him that the site, and the subject of the painting, fell outside of the everyday. More recent scholarship has supported Lhote’s belief in the painting’s symbolic, rather than literal, representation. As Jitka Soukopova has noted, “Hunter- gatherers were unlikely to wear horns (or other accessories on the head) and to make paintings on their whole bodies in their ordinary life.”[1] . Rather, this female horned figure, her body adorned and decorated, found in one of the highest massifs in the Tassili—a region is believed to hold special status due to its elevation and unique topology—suggests ritual, rite, or ceremony.

But there is further work to be done to advance an interpretation of the Running Horned Woman. Increasingly scholars have studied rock shelter sites as a whole, rather than isolating individual depictions, and the shelter’s location relative to the overall landscape and nearby water courses, in order to learn the significance of various “rock cities” in both image making and image viewing.

Archaeological data from decorated pottery, which is a dated artistic tradition, is key in suggesting that the concept of art was firmly established in the Central Sahara at the time of Tassili rock art production. Comparative studies with other rock art complexes, specifically the search for similarities in fundamental concepts in African religious beliefs, might yield the most fruitful approaches to interpretation. In other words, just as southern African rock studies have benefitted from tracing the beliefs and practices of the San people, so too may a study of Tuareg ethnography shed light on the ancient rock art sites of the Tassili.

Afterword: the threatened rock art of the Central Sahara

Tassili’s rock walls were commonly sponged with water in order to enhance the reproduction of its images, either in trace, sketch, or photograph. This washing of the rock face has had a devastating effect on the art, upsetting the physical, chemical, and biological balance of the images and their rock supports. Many of the region’s subsequent visitors—tourists, collectors, photographers, and the next generation of researchers—all captivated by Lhote’s “discovery”—have continued the practice of moistening the paintings in order to reveal them. Today scholars report paintings that are severely faded while some have simply disappeared. In addition, others have suffered from irreversible damage caused by outright vandalism: art looted or stolen as souvenirs. In order to protect this valuable center of African rock art heritage, Tassili N’Ajjer was declared a National Park in 1972. It was classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982 and a Biosphere Reserve in 1986.

[1] Jitka Soukopova, “The Earliest Rock Paintings of the Central Sahara: Approaching Interpretation,” Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture 4, no. 2 (2011), p. 199.

Additional resources

African Rock Art: TassilinAjjer – Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Tassili n’Ajjer – African World Heritage Sites

TARA – Trust for African Rock Art: Algeria and TARA Interactive Rock Art Map

David Coulson and Alec Campbell, African Rock Art: Paintings and Engravings on Stone (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001).

David Coulson and Alec Campbell, “Rock Art of the Tassili n Ajjer, Algeria.” Adoranten, no. 1 (2010), p. 115.

Jeremy H. Keenan, “The Lesser Gods of the Sahara.” Public Archaeology 2, no. 3 (2002), pp. 131-50.

Jean Dominque Lajoux, The Rock Paintings of Tassili, translated by G. D. Liversage (London: Thames and Hudson, 1963).

Henri Lhote, The Search for the Tassili Frescoes, translated by Alan H. Brodrick (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1959).

Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus

by UNESCO

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Source: UNESCO TV / © NHK Nippon Hoso Kyokai URL: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/287/.

On the borders of Tassili N’Ajjer in Algeria, also a World Heritage site, this rocky massif has thousands of cave paintings in very different styles, dating from 12,000 B.C.E. to 100 C.E.. They reflect marked changes in the fauna and flora, and also the different ways of life of the populations that succeeded one another in this region of the Sahara.

Egypt

Ancient Egypt

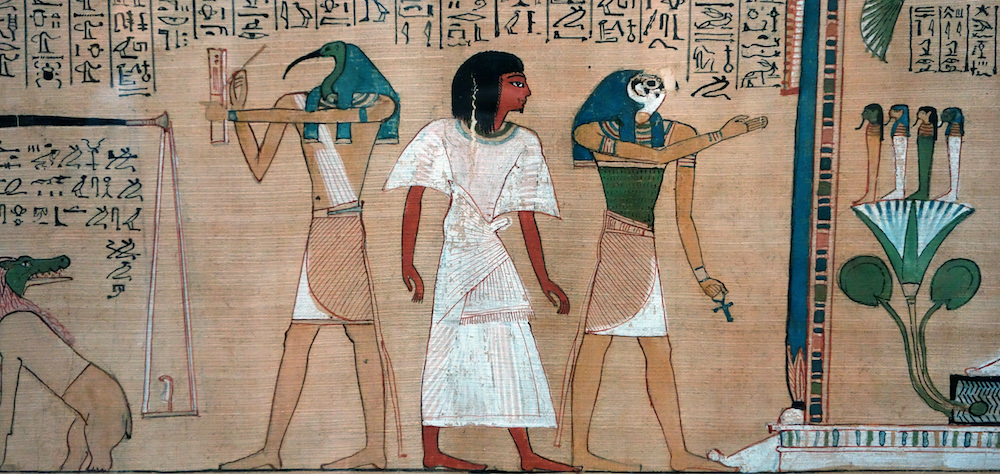

by DR. PERI KLEMM

Since the arts of ancient Egypt have conceptual, thematic, and stylistic connections to the traditional arts of Africa, Mediterranean cultures, and the Islamic world, it is difficult to place them in one geographic category. In general, Egyptologists study ancient Egypt as it connects to the ancient world beyond Africa so Smarthistory and most art history textbooks have chosen to place the bulk of Egyptian artworks within the Ancient Mediterranean section. Many scholars agree that an explicitly Western approach to the study of Egyptian art is problematic and a new, rich field of study that addresses ancient art within the framework of African art history is underway. By including links to ancient Egypt art here, we hope to remind readers of Egypt’s firm placement within North Africa and the need to examine this work from various disciplinary perspectives.

The art of Tunisia

One of the earliest mosques in Africa is found here.

670 - 900 C.E.

The Great Mosque of Kairouan

A new city

Seventh-century North Africa was not the easiest place to establish a new city. It required battling Byzantines; convincing Berbers, the indigenous people of North Africa, to accept centralized Muslim rule; and persuading Middle Eastern merchants to move to North Africa. So, in 670 CE, conquering general Sidi Okba constructed a Friday Mosque (masjid-i jami` or jami`) in what was becoming Kairouan in modern day Tunisia. A Friday Mosque is used for communal prayers on the Muslim holy day, Friday. The mosque was a critical addition, communicating that Kairouan would become a cosmopolitan metropolis under strong Muslim control, an important distinction at this time and place.

Known as the Great Mosque of Kairouan, it is an early example of a hypostyle mosque that also reflects how pre-Islamic and eastern Islamic art and motifs were incorporated into the religious architecture of Islamic North Africa. The aesthetics signified the Great Mosque and Kairouan, and, thus, its patrons, were just as important as the religious structures, cities, and rulers of other empires in this region, and that Kairouan was part of the burgeoning Islamic empire.

The Aghlabids

During the eighth century, Sidi Okba’s mosque was rebuilt at least twice as Kairouan prospered. However, the mosque we see today is essentially ninth century. The Aghlabids (800-909 C.E.) were the semi-independent rulers of much of North Africa. In 836, Prince Ziyadat Allah I tore down most of the earlier mudbrick structure and rebuilt it in more permanent stone, brick, and wood. The prayer hall or sanctuary is supported by rows of columns and there is an open courtyard, that are characteristic of a hypostyle plan.

In the late ninth century, another Aghlabid ruler embellished the courtyard entrance to the prayer space and added a dome over the central arches and portal. The dome emphasizes the placement of the mihrab, or prayer niche (below), which is on the same central axis and also under a cupola to signify its importance.

The dome is an architectural element borrowed from Roman and Byzantine architecture. The small windows in the drum of the dome above the mihrab space let natural light into what was an otherwise dim interior. Rays fall around the most significant area of the mosque, the mihrab. The drum rests on squinches, small arches decorated with shell over rosette designs similar to examples in Roman, Byzantine, and Umayyad Islamic art. The stone dome is constructed of twenty four ribs that each have a small corbel at their base, so the dome looks like a cut cantaloupe, according to the architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell.

Other architectural elements link the Great Mosque of Kairouan with earlier and contemporary Islamic religious structures and pre-Islamic buildings. They also show the joint religious and secular importance of the Great Mosque of Kairouan. Like other hypostyle mosques, such as the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, the mosque of Kairouan is roughly rectangular. Wider aisles leading to the mihrab and along the qibla wall give it a T-plan. The sanctuary roof and courtyard porticos are supported by repurposed Roman and Byzantine columns and capitals.

The lower portion of the mihrab is decorated with openwork marble panels in floral and geometric vine designs. Though the excessively decorated mihrab is unique, the panels are from the Syrian area. Around the mihrab are lustre tiles from Iraq. They also feature stylized floral patterns like Byzantine and eastern Islamic examples.

Since it was used for Friday prayer, the mosque has a ninth-century minbar, a narrow wooden pulpit where the weekly sermon was delivered. It is said to be the oldest surviving wooden minbar. Like Christian pulpits, the minbar made the prayer leader more visible and audible. Because a ruler’s legitimacy could rest upon the mention of his name during the sermon, the minbar served both religious and secular purposes. The minbar is made from teak imported from Asia, an expensive material exemplifying Kairouan’s commercial reach. The side of the minbar closest to the mihrab is composed of elaborately carved latticework with vegetal, floral, and geometric designs evocative of those used in Byzantine and Umayyad architecture.

The minaret dates from the early ninth century, or at least its lower portion does. Perhaps inspired by Roman lighthouses, the massive square Kairouan minaret is about thirty two meters tall, over one hundred feet, making it one of the highest structures around. So in addition to functioning as a place to call for prayer, the minaret identifies the mosque’s presence and location in the city while helping to define the city’s religious identity. As it was placed just off the mihrab axis, it also affirmed the mihrab’s importance.

The mosque continued to be modified after the Aghlabids, showing that it remained religiously and socially significant even as Kairouan fell into decline. A Zirid, al-Mu‘izz ibn Badis (ruled 1016-62 CE), commissioned a wooden maqsura, an enclosed space within a mosque that was reserved for the ruler and his associates. The maqsura is assembled from cutwork wooden screens topped with bands of carved abstracted vegetal motifs set into geometric frames, kufic-style script inscriptions, and merlons, which look like the crenellations a top a fortress wall. Maqsuras are said to indicate political instability in a society. They remove a ruler from the rest of the worshippers. So, the enclosure, along with its inscription, protected the lives and affirmed the status of persons allowed inside.

In the thirteenth century, the Hafsids gave the mosque a more fortified look when they added buttresses to support falling exterior walls, a practice continued in later centuries. In 1294, Caliph al-Mustansir restored the courtyard and added monumental portals, such as Bab al-Ma on the east and the domed Bab Lalla Rejana on the west. Additional gates were constructed in later centuries. Carved stone panels inside the mosque and on the exterior acted like billboards advertising which patron was responsible for construction and restoration.

An intellectual center

The Great Mosque was literally and figuratively at the center of Kairouan activity, growth, and prestige. Though the mosque is now near the northwest city ramparts established in the eleventh century, when Sidi Okba founded Kairouan, it was probably closer to the center of town, near what was the governor’s residence and the main thoroughfare, a symbolically prominent and physical visible part of the city. By the mid-tenth century, Kairouan became a thriving settlement with marketplaces, agriculture imported from surrounding towns, cisterns supplying water, and textile and ceramic manufacturing areas. It was a political capital, a pilgrimage city, and intellectual center, particularly for the Maliki school of Sunni Islam and the sciences. The Great Mosque had fifteen thoroughfares leading from it into a city that may have had a circular layout like Baghdad, the capital of the Islamic empire during Kairouan’s heyday. As a Friday Mosque, it was one of if not the largest buildings in town.

The Great Mosque of Kairouan was a public structure, set along roads that served a city with a vibrant commercial, educational, and religious life. As such, it assumed the important function of representing a cosmopolitan and urbane Kairouan, one of the first cities organized under Muslim rule in North Africa. Even today, the Great Mosque of Kairouan reflects the time and place in which it was built.

Additional resources:

Images of the mosque from Manar Al-Athar (University of Oxford)

Sheila S. Blair and Jonathan M. Bloom, The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800 (New York: Yale University Press, 1995).

K. A. C. Creswell and James W. Allan, A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture (Cairo: The American University of Cairo Press, 1989).

Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Islamic Art and Architecture, 650-1250 (New York: Yale University Press, 2001).

Peter Harrison, Castles of God: Fortified Religious Buildings of the World (Rochester: Boydell Press, 2004).

Robert Hillenbrand, Islamic Architecture: form, function, and meaning (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

John D. Hoag, Islamic Architecture, New York: Electa/Rizzoli, 1975.

Ira Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, 2nd edition (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Mourad Rammah, “Kairouan,” Museum with no Frontiers, Islamic Art in the Mediterranean, Ifriqiya. Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia (Vienna: Electa, 2002).

Andrew Petersen, Dictionary of Islamic Architecture (New York: Routledge, 1999).

Kairouan (from UNESCO)

by UNESCO

Video \(\PageIndex{24}\): Video from UNESCO TV / © NHK Nippon Hoso Kyokai

Founded in 670, Kairouan flourished under the Aghlabid dynasty in the 9th century. Despite the transfer of the political capital to Tunis in the 12th century, Kairouan remained the Maghreb’s principal holy city. Its rich architectural heritage includes the Great Mosque, with its marble and porphyry columns, and the 9th-century Mosque of the Three Gates.