4.4: Ancient Egyptian Religion

- Page ID

- 103510

https://www.worldhistory.org/Egyptian_Religion/

Definition

Pyramidion of Ramose [Detail] Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

Egyptian religion was a combination of beliefs and practices which, in the modern day, would include Egyptian mythology, science, medicine, psychiatry, magic, spiritualism, herbology, as well as the modern understanding of 'religion' as belief in a higher power and a life after death.

Religion played a part in every aspect of the lives of the ancient Egyptians because life on earth was seen as only one part of an eternal journey, and in order to continue that journey after death, one needed to live a life worthy of continuance. During one's life on earth, one was expected to uphold the principle of ma'at (harmony) with an understanding that one's actions in life affected not only one's self but others' lives as well, and the operation of the universe. People were expected to depend on each other to keep balance as this was the will of the gods to produce the greatest amount of pleasure and happiness for humans through a harmonious existence which also enabled the gods to better perform their tasks.

By honoring the principle of ma'at (personified as a goddess of the same name holding the white feather of truth) and living one's life in accordance with its precepts, one was aligned with the gods and the forces of light against the forces of darkness and chaos, and assured one's self of a welcome reception in the Hall of Truth after death and a gentle judgment by Osiris, the Lord of the Dead.

The Gods

The underlying principle of Egyptian religion was known as heka (magic) personified in the god Heka. Heka had always existed and was present in the act of creation. He was the god of magic and medicine but was also the power which enabled the gods to perform their functions and allowed human beings to commune with their gods. He was all-pervasive and all-encompassing, imbuing the daily lives of the Egyptians with magic and meaning and sustaining the principle of ma'at upon which life depended.

Possibly the best way to understand Heka is in terms of money: one is able to purchase a particular item with a certain denomination of currency because that item's value is considered the same, or less, than that denomination. The bill in one's hand has an invisible value given it by a standard of worth (once upon a time the gold standard) which promises a merchant it will compensate for what one is buying. This is exactly the relationship of Heka to the gods and human existence: he was the standard, the foundation of power, on which everything else depended. A god or goddess was invoked for a specific purpose, was worshipped for what they had given, but it was Heka who enabled this relationship between the people and their deities.

The gods of ancient Egypt were seen as the lords of creation and custodians of order but also as familiar friends who were interested in helping and guiding the people of the land. The gods had created order out of chaos and given the people the most beautiful land on earth. Egyptians were so deeply attached to their homeland that they shunned prolonged military campaigns beyond their borders for fear they would die on foreign soil and would not be given the proper rites for their continued journey after life. Egyptian monarchs refused to give their daughters in marriage to foreign rulers for the same reason. The gods of Egypt had blessed the land with their special favor, and the people were expected to honor them as great and kindly benefactors.

THE GODS OF ANCIENT EGYPT WERE SEEN AS THE LORDS OF CREATION & CUSTODIANS OF ORDER BUT ALSO AS FAMILIAR FRIENDS WHO WERE INTERESTED IN HELPING & GUIDING THE PEOPLE OF THE LAND.

Long ago, they believed, there had been nothing but the dark swirling waters of chaos stretching into eternity. Out of this chaos (Nu) rose the primordial hill, known as the ben-ben, upon which stood the great god Atum (some versions say the god was Ptah but many others that it was Ra who eventually was known as Atum-Ra) in the presence of Heka.

Atum-Ra looked upon the nothingness and recognized his aloneness, and so he mated with his own shadow to give birth to two children, Shu (god of air, whom Atum-Ra spat out) and Tefnut (goddess of moisture, whom Atum-Ra vomited out). Shu gave to the early world the principles of life while Tefnut contributed the principles of order. Leaving their father on the ben-ben, they set out to establish the world.

In time, Atum-Ra became concerned because his children were gone so long, and so he removed his eye and sent it in search of them. While his eye was gone, Atum-Ra sat alone on the hill in the midst of chaos and contemplated eternity. Shu and Tefnut returned with the eye of Atum-Ra (later associated with the Udjat eye, the Eye of Ra, or the All-Seeing Eye) and their father, grateful for their safe return, shed tears of joy. These tears, dropping onto the dark, fertile earth of the ben-ben, gave birth to men and women.

These humans had nowhere to live, however, and so Shu and Tefnut mated and gave birth to Geb (the earth) and Nut (the sky). Geb and Nut, though brother and sister, fell deeply in love and were inseparable. Atum-Ra found their behaviour unacceptable and pushed Nut away from Geb, high up into the heavens. The two lovers were forever able to see each other but were no longer able to touch. Nut was already pregnant by Geb, however, and eventually gave birth to Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys, and Horus – the five Egyptian gods most often recognized as the earliest (although Hathor is now considered to be older than Isis). These gods then gave birth to all the other gods in one form or another.

Horus Statuette Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin (CC BY-NC-SA)

The gods each had their own area of specialty. Bastet, for example, was the goddess of the hearth, home life, women's health and secrets, and of cats. Hathor was the goddess of kindness and love, associated with gratitude and generosity, motherhood, and compassion. According to one early story surrounding her, however, known as the Book of the Heavenly Cow, she was sent to earth to destroy humanity and became the goddess Sekhmet who, drunk on blood, almost destroyed the world until she was pacified and put to sleep by beer which the gods had dyed red to fool her.

When she awoke from her sleep, she was transformed into the gentler deity Hathor who pledged her eternal service to humanity. Although Hathor was associated with beer, Tenenet was the principal goddess of the beverage and also presided over childbirth. Beer was considered essential for one's health in ancient Egypt and a gift from the gods, and there were many deities associated with the drink which was said to have been first brewed by Osiris.

An early myth tells of how Osiris was tricked and killed by his brother Set and how Isis brought him back to life. He was incomplete, however, as a fish had eaten a part of him, and so he could no longer rule harmoniously on earth and was made Lord of the Dead in the underworld. His son, Horus the Younger, battled Set for eighty years and finally defeated him to restore harmony to the land. Horus and Isis then ruled together, and all the other gods found their places and areas of expertise to help and encourage the people of Egypt.

Among the most important of these gods were the three who made up the Theban Triad: Amun, Mut, and Knons (also known as Khonsu). Amun was a local fertility god of Thebes until the Theban noble Menuhotep II (2061-2010 BCE) defeated his rivals and united Egypt, elevating Thebes to the position of capital and its gods to supremacy. Amun, Mut, and Khons of Upper Egypt (where Thebes was located) took on the attributes of Ptah, Sekhmet, and Khonsu of Lower Egypt who were much older deities. Amun became the supreme creator god, symbolized by the sun; Mut was his wife, symbolized by the sun's rays and the all-seeing eye; and Khons was their son, the god of healing and destroyer of evil spirits.

These three gods were associated with Ogdoad of Hermopolis, a group of eight primordial deities who "embodied the qualities of primeval matter, such as darkness, moistness, and lack of boundaries or visible powers. It usually consisted of four deities doubled to eight by including female counterparts" (Pinch, 175-176). The Ogdoad (pronounced OG-doh-ahd) represented the state of the cosmos before land rose from the waters of chaos and light broke through the primordial darkness and were also referred to as the Hehu ('the infinities'). They were Amun and Amaunet, Heh and Hauhet, Kek and Kauket, and Nun and Naunet each representing a different aspect of the formless and unknowable time before creation: Hiddenness (Amun/Amaunet), Infinity (Heh/Hauhet), Darkness (Kek/Kauket), and the Abyss (Nut/Naunet). The Ogdoad are the best example of the Egyptian's insistence on symmetry and balance in all things embodied in their male/female aspect which was thought to have engendered the principle of harmony in the cosmos before the birth of the world.

Harmony & Eternity

The Egyptians believed that the earth (specifically Egypt) reflected the cosmos. The stars in the night sky and the constellations they formed were thought to have a direct bearing on one's personality and future fortunes. The gods informed the night sky, even traveled through it, but were not distant deities in the heavens; the gods lived alongside the people of Egypt and interacted with them daily. Trees were considered the homes of the gods and one of the most popular of the Egyptian deities, Hathor, was sometimes known as "Mistress of the Date Palm" or "The Lady of the Sycamore" because she was thought to favor these particular trees to rest in or beneath. Scholars Oakes and Gahlin note that

Presumably because of the shade and the fruit provided by them, goddesses associated with protection, mothering, and nurturing were closely associated with [trees]. Hathor, Nut, and Isis appear frequently in the religious imagery and literature [in relation to trees]. (332)

Plants and flowers were also associated with the gods, and the flowers of the ished tree were known as "flowers of life" for their life-giving properties. Eternity, then, was not an ethereal, nebulous concept of some 'heaven' far from the earth but a daily encounter with the gods and goddesses one would continue to have contact with forever, in life and after death.

Hathor Mary Harrsch (Photographed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) (CC BY-NC-SA)

In order for one to experience this kind of bliss, however, one needed to be aware of the importance of harmony in one's life and how a lack of such harmony affected others as well as one's self. The 'gateway sin' for the ancient Egyptians was ingratitude because it threw one off balance and allowed for every other sin to take root in a person's soul. Once one lost sight of what there was to be grateful for, one's thoughts and energies were drawn toward the forces of darkness and chaos.

This belief gave rise to rituals such as The Five Gifts of Hathor in which one would consider the fingers of one's hand and name the five things in life one was most grateful for. One was encouraged to be specific in this, naming anything one held dear such as a spouse, one's children, one's dog or cat, or the tree by the stream in the yard. As one's hand was readily available at all times, it would serve as a reminder that there were always five things one should be grateful for, and this would help one to maintain a light heart in keeping with harmonious balance. This was important throughout one's life and remained equally significant after one's death since, in order to progress on toward an eternal life of bliss, one's heart needed to be lighter than a feather when one stood in judgment before Osiris.

The Soul & The Hall of Truth

According to the scholar Margaret Bunson:

The Egyptians feared eternal darkness and unconsciousness in the afterlife because both conditions belied the orderly transmission of light and movement evident in the universe. They understood that death was the gateway to eternity. The Egyptians thus esteemed the act of dying and venerated the structures and the rituals involved in such a human adventure. (86)

The structures of the dead can still be seen throughout Egypt in the modern day in the tombs and pyramids which still rise from the landscape. There were structures and rituals after life, however, which were just as important.

The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts:

- Khat was the physical body

- Ka was one's double-form

- Ba was a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens

- Shuyet was the shadow self

- Akh was the immortal, transformed self

- Sahu and Sechem were aspects of the Akh

- Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil

- Ren was one's secret name.

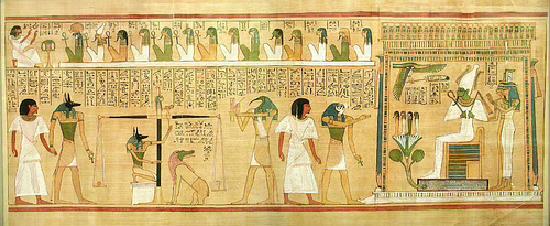

All nine of these aspects were part of one's earthly existence and, at death, the Akh (with the Sahu and Sechem) appeared before the great god Osiris in the Hall of Truth and in the presence of the Forty-Two Judges to have one's heart (Ab) weighed in the balance on a golden scale against the white feather of truth.

One would need to recite the Negative Confession (a list of those sins one could honestly claim one had not committed in life) and then one's heart was placed on the scale. If one's heart was lighter than the feather, one waited while Osiris conferred with the Forty-Two Judges and the god of wisdom, Thoth, and, if considered worthy, was allowed to pass on through the hall and continue one's existence in paradise; if one's heart was heavier than the feather it was thrown to the floor where it was devoured by the monster Ammut (the gobbler), and one then ceased to exist.

Weighing the Heart, Book of the Dead Jon Bodsworth (Public Domain)

Once through the Hall of Truth, one was then guided to the boat of Hraf-haf ("He Who Looks Behind Him"), an unpleasant creature, always cranky and offensive, whom one had to find some way to be kind and courteous to. By showing kindness to the unkind Hraf-haf, one showed one was worthy to be ferried across the waters of Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) to the Field of Reeds which was a mirror image of one's life on earth except there was no disease, no disappointment, and no death. One would then continue one's existence just as before, awaiting those one loved in life to pass over themselves or meeting those who had gone on before.

The Clergy, Temples & Scripture

Although the Greek historian Herodotus claims that only men could be priests in ancient Egypt, the Egyptian record argues otherwise. Women could be priests of the cult of their goddess from the Old Kingdom onward and were accorded the same respect as their male counterparts. Usually a member of the clergy had to be of the same sex as the deity they served. The cult of Hathor, most notably, was routinely attended to by female clergy (it should be noted that 'cult' did not have the same meaning in ancient Egypt that it does today. Cults were simply sects of one religion). Priests and Priestesses could marry, have children, own land and homes and lived as anyone else except for certain ritual practices and observances regarding purification before officiating. Bunson writes:

In most periods, the priests of Egypt were members of a family long connected to a particular cult or temple. Priests recruited new members from among their own clans, generation after generation. This meant that they did not live apart from their own people and thus maintained an awareness of the state of affairs in their communities. (209)

Priests, like scribes, went through a prolonged training period before beginning service and, once ordained, took care of the temple or temple complex, performed rituals and observances (such as marriages, blessings on a home or project, funerals), performed the duties of doctors, healers, astrologers, scientists, and psychologists, and also interpreted dreams. They blessed amulets to ward off demons or increase fertility, and also performed exorcisms and purification rites to rid a home of ghosts.

Their chief duty was to the god they served and the people of the community, and an important part of that duty was their care of the temple and the statue of the god within. Priests were also doctors in the service of Heka, no matter what other deity they served directly. An example of this is how all the priests and priestesses of the goddess Serket (Selket) were doctors but their ability to heal and invoke Serket was enabled through the power of Heka.

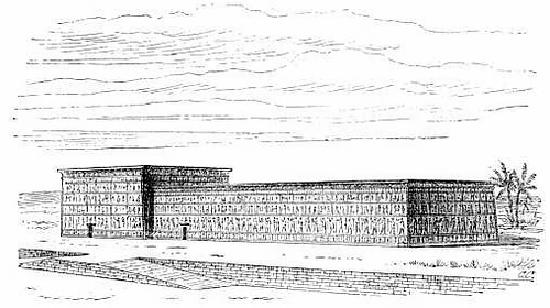

The temples of ancient Egypt were thought to be the literal homes of the deities they honored. Every morning the head priest or priestess, after purifying themselves with a bath and dressing in clean white linen and clean sandals, would enter the temple and attend to the statue of the god as they would to a person they were charged to care for.

The doors of the sanctuary were opened to let in the morning light, and the statue, which always resided in the innermost sanctuary, was cleaned, dressed, and anointed with oil; afterwards, the sanctuary doors were closed and locked. No one but the head priest was allowed such close contact with the god. Those who came to the temple to worship only were allowed in the outer areas where they were met by lesser clergy who addressed their needs and accepted their offerings.

Egyptian Temple Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez (1883) (Public Domain)

There were no official 'scriptures' used by the clergy but the concepts conveyed at the temple are thought to have been similar to those found in works such as the Pyramid Texts, the later Coffin Texts, and the spells found in the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Although the Book of the Dead is often referred to as 'The Ancient Egyptian Bible' it was no such thing. The Book of the Dead is a collection of spells for the soul in the afterlife. The Pyramid Texts are the oldest religious texts in ancient Egypt dating from c. 2400-2300 BCE. The Coffin Texts were developed later from the Pyramid Texts c. 2134-2040 BCE while the Book of the Dead (actually known as the Book of Coming Forth by Day) was set down sometime c. 1550-1070 BCE.

All three of these works deal with how the soul is to navigate the afterlife. Their titles (given by European scholars) and the number of grand tombs and statuary throughout Egypt, not to mention the elaborate burial rituals and mummies, have led many people to conclude that Egyptian culture was obsessed with death when, actually, the Egyptians were wholly concerned with life. The Book of Coming Forth by Day, as well as the earlier texts, present spiritual truths one would have heard while in life and remind the soul of how one should now act in the next phase of one's existence without a physical body or a material world. The soul of any Egyptian was expected to recall these truths from life, even if they never set foot inside a temple compound, because of the many religious festivals the Egyptians enjoyed throughout the year.

Religious Festivals & Religious Life

Religious festivals in Egypt integrated the sacred aspect of the gods seamlessly with the daily lives of the people. Egyptian scholar Lynn Meskell notes that "religious festivals actualized belief; they were not simply social celebrations. They acted in a multiplicity of related spheres" (Nardo, 99). There were grand festivals such as The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi in honor of the god Amun and lesser festivals for other gods or to celebrate events in the life of the community.

Bunson writes, "On certain days, in some eras several times a month, the god was carried on arks or ships into the streets or set sail on the Nile. There the oracles took place and the priests answered petitions" (209). The statue of the god would be removed from the inner sanctuary to visit the members of the community and take part in the celebration; a custom which may have developed independently in Egypt or come from Mesopotamia where this practice had a long history.

The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi was a celebration of life, wholeness, and community, and, as Meskell notes, people attended this festival and visited the shrine to "pray for bodily integrity and physical vitality" while leaving offerings to the god or goddess as a sign of gratitude for their lives and health. Meskell writes:

One may envisage a priest or priestess coming and collecting the offerings and then replacing the baskets, some of which have been detected archaeologically. The fact that these items of jewelry were personal objects suggests a powerful and intimate link with the goddess. Moreover, at the shrine site of Timna in the Sinai, votives were ritually smashed to signify the handing over from human to deity, attesting to the range of ritual practices occurring at the time. There was a high proportion of female donors in the New Kingdom, although generally tomb paintings tend not to show the religous practices of women but rather focus on male activities. (101)

The smashing of the votives signified one's surrender to the benevolent will of the gods. A votive was anything offered in fulfillment of a vow or in the hopes of attaining some wish. While votives were often left intact, they were sometimes ritually destroyed to signify the devotion one had to the gods; one was surrendering to them something precious which one could not take back.

There was no distinction at these festivals between those acts considered 'holy' and those which a modern sensibility would label 'profane'. The whole of one's life was open for exploration during a festival, and this included sexual activity, drunkenness, prayer, blessings for one's sex life, for one's family, for one's health, and offerings made both in gratitude and thanksgiving and in supplication.

Families attended the festivals together as did teenagers and young couples and those hoping to find a mate. Elder members of the community, the wealthy, the poor, the ruling class, and the slaves were all a part of the religious life of the community because their religion and their daily lives were completely intertwined and, through that faith, they recognized their individual lives were all an interwoven tapestry with every other.

Bibliography

- Allen, J. P. The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. SBL Press, 2015.

- Bunson, M. Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Gramercy Books, 1991.

- Champollion, J. World of the Egyptians. W.& G. Foyle Ltd, 1971.

- Gibson, C. The Hidden Life of Ancient Egypt. Fall River Press, 2009.

- Nardo, D. Living in Ancient Egypt. Greenhaven Press, 2004.

- Oakes, L. & Gahlin, L. Ancient Egypt. Anness Publishing, Ltd., 2008.

- Pinch, G. Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Shaw, I. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Wallis-Budge, E. A. The Egyptian Book of the Dead. Dover Publications, 1967.

- Wilkinson, R. H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2017.

Contributors and Attributions

Joshua J. Mark

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.