3.4: Musical Theatre

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

The wildly popular theatrical genre known as musical theatre is often the gateway experience for newcomers to the world of theatre. Combining all three of the performing arts (dance, music, and theatre), it provides an opportunity for each audience member to find something they enjoy. The razzle-dazzle of the spectacle, powerful soaring voices, snazzy memorable tunes, and impeccable dancing seduce even the most reluctant of theatregoers. Audiences sit in wonder before the show begins, gazing at the often elaborate scenic design, and waiting on bated breath to be captivated by this compelling art form. The stories – the new, the newly adapted, and the old — invite audiences from across generations. It has been said, in fact, that musical theatre is the one original theatrical form solely contributed by America; though this comment is perhaps intended as a dig, judging by its Commercial Broadway success, this is an accolade we Americans can proudly hail.

A Bit of History

The Beginning

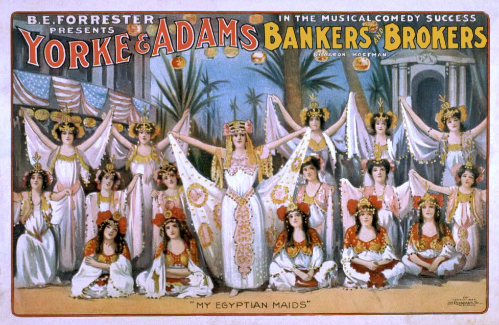

Open five different theatre textbooks and you will likely find five different starting points for tracing the origins of the musical. Some historians will link it all the way back to the Greeks’ use of music and dance in plays, while others point to Gilbert and Sullivan, or Irish immigrants, and still, others begin with 18th and 19th Century comic opera, vaudeville, and burlesque. While the inclusion of music and dance in theatre has indeed existed for thousands of years and has certainly influenced the creation of musical theatre, a production known as The Black Crook in 1866 is most often distinguished as the “first” musical, but even this title has now been categorized as musical comedy by today’s standards.

Musical comedy, as we’ve come to identify it today, would continue to delight audiences throughout the early 20th Century. But in 1927, Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein’s Show Boat would change the face of musical theatre. The production was the first to bring serious social issues to the stage depicting real people with real problems. Show Boat combined all the best elements of its predecessors in terms of structure – timing, song formulas, characters, and settings – and ventured into the world of musical drama. Show Boat’s evolution of the musical sparked a wave of new work, ushering in the Golden Age of Musical Theatre.

The Golden Age

The 1930s and 40s would prove to be a challenging time for Americans. The Great Depression followed by World War II would leave the country in need of a welcome distraction to keep spirits bright. This resulted in the rise of some of the greatest American musical theatre composers and lyricists, such as George and Ira Gershwin, whose first major hit Of Thee I Sing, won the Pulitzer Prize for drama — the first musical to hold this honor. Cole Porter would also produce his smash hit, Anything Goes, full of catchy tunes such as “I Get a Kick Out of You,” and “Blow, Gabriel, Blow”. The classic musical would also emerge, created by one of the longest and most productive musical theatre partnerships in history between composer, Richard Rodgers, and lyricist, Oscar Hammerstein. Their first hit, Oklahoma! would change the rules of musical theatre forever and become one of the most important musicals in musical theatre history. We will take a deeper dive into this groundbreaking musical and how it changed the face of musical theatre later in the chapter.

The 1950s would charge onto the scene with popular titles such as Guys and Dolls, My Fair Lady, West Side Story, and The Music Man. Television and its growing popularity during this time were having an impact on musical theatre audiences, increasing popularity and making songs and stories more accessible. Guys and Dolls, considered by most historians to be one of the most perfect musicals ever written, became popular for its memorable songs like “Sit Down You’re Rocking the Boat” and “Bushel and a Peck” and its all too familiar plot line – a woman’s need to find a man to marry – a plight all too familiar to women of this time. By the late 50s, the musical tragedy West Side Story would open, once again shifting the musical theatre scene with its groundbreaking ideas. We will explore this title in more detail later in the chapter.

The Unrest

The Civil Rights Movement presses forward and the entrance of the country into the Vietnam War marks two of the most significant factors in the ongoing unrest in the United States during this time. Consequently, audiences craved something different – no more conventional musicals and romantic notions. In sweeps How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, a clever satire mocking corporate America and paving the way for momentous change. Even the more traditional musicals, such as 1964’s Hello Dolly!, would delight audiences with Dolly Levi’s unpredictable nature and striking independence. Director, Hal Prince, and director/choreographer, Bob Fosse, would emerge as leaders in the industry, moving musical theatre to become more socially responsible. Groundbreaking productions such as Cabaret and Hair would pave the way for the 1970s and the introduction of the concept musical and one of today’s most popular forms, the rock musical. George Furth and Stephen Sondheim’s Company (currently experiencing a brilliant 2021 revival on Broadway directed by Marianne Elliott), would emerge as the first concept musical. Critics were not in agreement as to whether Company was “good”, but they did agree that it was different and brave for its changes to the common musical theatre structure, most notably characters outside of the scene singing the songs as a commentary on what’s happening within each couple’s life. Company is one of many productions which became pillars of this era, including Pippin, Jesus Christ Superstar, The Rocky Horror Show, Chicago, and A Chorus Line, which we will study in greater detail later in the chapter.

The Commercialization of Broadway

The 1980s is often deemed a boring era for musical theatre due to many failed musicals full of plot lines that were simply not engaging audiences. The need for something new and perhaps “sparkly” to entice audiences led to the success of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats, the theatrical event that established the megamusical. The megamusical phenomenon, a blockbuster extravaganza with huge commercial profits, would become the face of Broadway in the 1980s. Les Miserables, The Phantom of the Opera, Miss Saigon, Beauty and the Beast, and The Lion King would soon follow Cats. The jukebox musical would also become a popular hit during this era with the smash hit, Mamma Mia, which would also be categorized as a megamusical due to its box office success. Often grossing into the billions, these megamusicals would become the driving force for where Broadway was headed. No one can deny the appeal of the spectacle and sheer awe of these megamusical productions. But at what cost? The 1990s would begin to shift Broadway back toward socially relevant stories that would challenge audiences. Titles such as Sondheim’s Assassins and Jonathan Larson’s RENT, which we learn much more about later in the chapter, would assist in this endeavor. Jason Robert Brown, a new writer and composer, would also emerge and begin to draw attention with his new work, Parade.

The New Millennium

The bright lights of Broadway would dim after the attacks of September 11, 2001. While Broadway would only remain closed for 2 nights, audiences were reluctant to return for weeks. Despite this, most of the shows were able to remain open, including The Producers, a Mel Brooks comedy, which had shattered box office records with its witty and satirical humor wrapped in a conventional musical theatre bow. Contemporary audiences proved yet again that they would turn out for a good satire, setting the stage for similar works such as Avenue Q, Spamalot, and eventually The Book of Mormon. Meanwhile, LA’s Deaf West Theatre would take center stage with its revival of Big River featuring a cast of both hearing and non-hearing actors, using sign language onstage, and at times utilizing two actors playing the same character onstage, one hearing and one non-hearing. Inclusive work such as this would light the path for future work to represent a more diverse population in their storytelling and in the artists hired by producing and creative teams; a notable and crucial step forward for musical theatre. Other notable works during this period were The Light in the Piazza, Kinky Boots, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Wicked, Spring Awakening, Dear Evan Hansen, and of course, Hamilton.

Having gained a bit more information on the history of musical theatre in America, let us take a deeper look at four significant musicals which, each within their own right, assisted in the progression of the modern-day musical.

Oh, What a Beautiful Morning

Historians and musical theatre scholars agree, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! was expected to fail in 1934. Surprising given its incredible box office success and subsequent notoriety. Let’s examine why it was expected to fail in order to better understand its importance in musical theatre. For starters, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein both had success on several previous projects, but never together. They were an entirely new team having worked with different partners on their former endeavors. Secondly, the director, Rouben Mamoulian, was given complete control of the production, which at the time was unprecedented and considered risky decision-making. Furthermore, the creative team cast an entirely unknown group of actors rather than the typical stars. They focused on finding actors they believed could act and sing the part, rather than relying on star power. The story itself was even part of the skepticism. These characters were everyday people living their lives in Oklahoma of all places – not the exciting settings most often seen in musicals up to this point. The musical also began with a single character onstage – and not a pretty young woman, but an older woman, Aunt Eller, churning butter in front of her farmhouse. The leading man, Curly, was off in the wings, not even visible to the audience, and he sang the beginning of the song completely acapella – a first, and a welcome surprise!

So how did Oklahoma! come to gain its popularity? Certainly, the rule applies here that the greater the risk, the bigger the reward. The success was in part due to the intelligent combination of all of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s past successful elements (think of them as the ingredients of a good musical), into one seamless production. The social issues of Show Boat were now combined with dramatic dance sequences, musical scenes, love triangles, and a full-fledged psychological dream ballet. Agnes de Mille’s choreography vividly depicted Laurey’s sexual desires, and her fears and struggle with the two men in her life, Jud and Curly. In fact, Agnes de Mille was the first choreographer to insist that the music be written to the choreography, rather than the other way around. She and her arranger composed the music for the 18-minute-long dream ballet.

Despite its meager expectations, Oklahoma! became a massive hit running for more than five years and offering 2,212 performances, which at the time was the longest run in Broadway history. The national tour would run for more than 10 years while productions mounted in London, Paris, and Berlin. During World War II, the production played for more than a million troops in the Pacific as part of the USO tour, helping to remind soldiers what they were fighting for back home. The most popular songs, “People Will Say We’re in Love” and “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning” would sell over a million albums and top the charts. The Broadway Cast recording would become the most-sold album in December of 1935. A blockbuster film would be created in 1955 and a revival starring Hugh Jackman and directed by Trevor Nunn would enchant audiences in London in the late 1990s. The musical has been awarded the Pulitzer Prize and received Tony’s, Olivier’s, Outer Critics, and Drama Desk awards. The New York Drama League voted it the musical of the century at the close of the 1900s, a well-deserved title for a musical that continues to play in nearly six hundred theatres each year.

Something’s Coming

1957’s West Side Story was the next great American musical following Oklahoma!. It was the brainchild of its original director/choreographer, Jerome Robbins, who was a choreographer at the time for the New York City Ballet. His co-creators included Leonard Bernstein (composer), Arthur Laurents (book), and joining late in the process was a young Stephen Sondheim (lyricist). Inspired by teenage Latin gang violence in LA in the mid-1950s, the story reimagines Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet swapping the Capulets and Montagues for feuding Puerto Rican and white gangs on the then-run-down Upper West Side of New York City. The team crafted the story of hatred and prejudice, making intelligent changes to Shakespeare’s work to increase the dramatic effect, altering the ending for Maria to live and be forced to struggle with the devastating loss of Tony and her brother for the rest of her life. This change intensifies the tragedy that was Romeo and Juliet and leaves audiences with the bitter truth, that regardless of any hope they may feel, hatred will not die. Similar to Oklahoma!, there were naysayers who believed the show would flop because it was too dark and tragic. In fact, the production lost its first producer for this reason and struggled to find another until Hal Prince stepped in and raised the funds necessary to move the show forward to opening night.

The show was not popular at first; audiences preferred to attend the light-hearted production of The Music Man instead. Until the movie premiered in 1961, the show did not gain traction. Latinx groups threatened to picket the production over the song, “America,” for its racist issues. The creative team was all white Jewish men, who had not done their research to learn that Puerto Ricans do not refer to “America” in that way. The Puerto Rican community referred to America as “The United States.” A cultural flaw in the story, and one of many according to the Latinx community. The production was also accused of glamorizing gangs and for its lack of authentic Latin casting. Was it an improvement over the MGM Latin musicals from the 1930s, sure, but better does not equal good. In fact, it would take decades for Lin-Manuel Miranda to come onto the scene with In the Heights, to catapult the conversation forward about the underrepresentation and misrepresentation of Latinx people in theatre.

West Side Story closed after just 732 performances. Its dissonant, jazz-inspired score and beautifully intricate dance would not keep it open. Once the film revived the work in 1961, several revivals would hit the stage, including a 2009 revival which included Lin-Manuel Miranda in the role of translator, as this production attempted to solve issues by including more Spanish. The production closed after 748 performances. A 2020 revival attempted to move the production into the present day, removing “I Feel Pretty” and reducing the book to tell the story without an intermission in merely an hour and forty-five minutes. The production received conflicting reviews due to its integration of large video screens, the shift away from Robbins’s ballet-inspired dance to hip-hop, and the inclusion of black actors in the Jets gang – a move that critics believe minimized the statement of racism in our country. The production would temporarily close on March 11, when all of Broadway shut down due to the COVID pandemic. It would not return, closing after only 24 performances.

I Hope I Get It

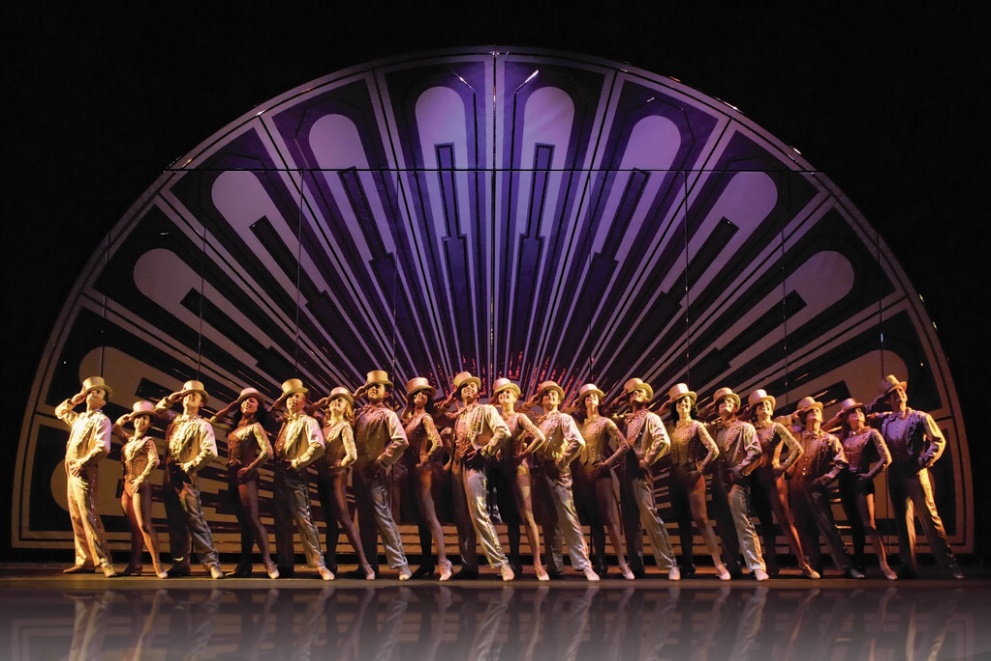

Launching a whole new genre, A Chorus Line, took the stage in 1975 as the first documentary musical. Tony Stevens and Michon Peacock had worked on a complete flop and determined they needed to create their own work to have any chance at a quality project. Director Michael Bennett soon joined them and they decided to gather a group of dancers to discuss their lives and work with the intended goal of creating the piece from these discussions. After Joseph Papp agreed to fund a workshop, Marvin Hamlisch (composer) joined the team, as did Ed Kleban (lyricist). Bennett had the dancers audition to play themselves and it was decided that the costumes would become what they were wearing that day up until the finale number when they would all appear in the sparking gold costumes with top hats. The set was simply a line of tape across the floor with mirrors upstage.

As if cutting the spectacle and firmly establishing a new genre wasn’t enough, the show also introduced subject matter that hadn’t been present (or at least wasn’t prominent) onstage before—cross-dressing, homosexuality, plastic surgery, divorce, and domestic violence, to name a few. It also revolutionized storytelling at a time when Broadway producers were struggling to pay an entire chorus. Moving forward, the chorus would now double in speaking roles, minimizing the number of actors needed in each production. More significantly, it brought a diverse group of actors to the stage. There were two Latinx characters, one Asian, one Jew, one black man, and multiple gay men. What an impressive shift!

Bennett said of the finale, “It will be the end of chorus lines as we know them. The audience will be horrified at how the chorus line robs the dancers of their personality… They won’t be able to applaud. They’ll be speechless.” Unfortunately, Bennett never got the reaction he was looking for, but at least for the dancers in the audience, the message was clear and appreciated. After a short run of 101 performances Off-Broadway at the Papp, A Chorus Line moved to Broadway and would stay until 1990 having run 6,137 performances. It was nominated for 12 Tony awards, winning Best Musical, Best Book, Best Score, Best Director, and Best Choreography. It would win countless other awards and become the longest-running musical on Broadway until being surpassed by CATS in 1997.

Seasons of Love

Jonathan Larson’s RENT would once again reshape musical theatre and the audience’s experience upon its opening in 1996. Inspired by Puccini’s opera, LaBoeme, RENT told the story of a group of artist friends who struggle to find their way and to find meaningful relationships in such a virulent world. As opposed to the focus on death in the original source material, RENT focused on LIFE. It was full of joy, vivacity, and charismatic characters. It was the first musical in years to appeal to a younger generation. Suddenly there were people onstage they could identify with, who used their language and struggled with the same issues they were facing. It shined a light on what many college graduates were feeling – lost and broke – wondering where to begin and how to make ends meet.

Larson’s dream to “bring musical theatre to the MTV generation” was a long time coming. The musical spent years in workshops at the New York Theatre Workshop, moving through rewrites and being trimmed down from its original 42 songs. During the workshops, Larson wrote a short statement to summarize the show. “RENT is about a community celebrating life, in the face of death and AIDS, at the turn of the century,” he said. This statement would become the creative team’s guiding light after Larson’s sudden death from a brain aneurism the night before the Off-Broadway premiere.

One of the most significant outcomes of RENT was the introduction of $20 theatre tickets for the first two rows of seats in the theatre. The seats became available at 6:00 p.m. the night of the performance. “Rent-heads”, as the fans of the production came to be known, would camp out for hours, even overnight on weekends, for a ticket. They could be found in a line often wrapping around the building with their tents, music, and food, passing the time as they waited for a chance to see this exciting new show. In 1997, this system would move to a lottery, but tickets would remain $20. This low-cost option began to spread to other Broadway theatres as well, finally making theatre more accessible.

RENT would take a toll on the voices of the actors who had the rigorous task of performing the challenging score eight times a week. It was not uncommon to see up to eight or nine actors out at any given time, replaced by understudies, as the leads became plagued by vocal fatigue. RENT managed to endure winning four Tony awards, six Drama Desk awards, and the Pulitzer Prize. It would play for 12 years, closing in 2008 as one of the longest-running Broadway musicals.

Bob Fosse

Cole Porter

Deaf West Theatre

Documentary Musical

George and Ira Gershwin

Gilbert and Sullivan

Guys and Dolls

Hal Prince

Jukebox Musical

Lin-Manuel Miranda

Megamusical

Musical Comedy

Off-Broadway

Show Boat

Stephen Sondheim

The Producers