3.5: Maintaining Resources

- Page ID

- 73585

Maintaining resources is an important activity in every organizing system because resources must be available at the time they are needed. Beyond these basic shared motivations are substantial differences in maintenance goals and methods depending on the domain of the organizing system.

However, different domains sometimes use the same terms to describe different maintenance activities and different terms for similar activities. Common maintenance activities are storage, preservation, curation, and governance. Storage is most often used when referring to physical or technological aspects of maintaining resources; backup (for short-term storage), archiving (for long-term storage), and migration (moving stored resources from one storage device to another) are similar in this respect. The other three terms generally refer to activities or methods that more closely overlap in meaning; we will distinguish them in “Preservation” through “Governance”.

Selection and maintenance are interdependent. Selection is based on an initial set of rules that determine which resources enter the organizing system. Maintenance includes the work to preserve the resources, the processes for evaluating and revising the original selection criteria, and the removal of resources from the system when they no longer need to be preserved. More stringent rules for selecting resources generally imply a maintenance plan that carefully enforces the same constraints that limit selection. This is just common sense whether the resource is a piece of art, an automobile, a software package, or a star basketball player; if you worked hard to find or paid a lot to acquire a resource, you are going to take care of it and will not soon be buying another one.

Ideally, maintenance requirements for resources should be anticipated when organizing principles are defined and implemented. Resource descriptions to support preservation of digital resources are especially important. [1]

Motivations for Maintaining Resources

The concept of memory institution broadly applies to a great many organizing systems that share the goal of preserving knowledge and cultural heritage.[2]The primary resources in libraries, museums, data archives or other memory institutions are fixed cultural, historic, or scientific artifacts that are maintained because they are unique and original items with future value. This is why the Musée du Louvre preserves the portrait of the Mona Lisa and the United States National Archives preserves the Declaration of Independence.[3]

In contrast, in businesses organizing systems, many of the resources that are collected and managed have limited intrinsic value. The motivation for preservation and maintenance is economic; resources are maintained because they are essential in running the business. For example, businesses collect and preserve information about employees, inventory, orders, invoices, etc., because it ensures internal goals of efficiency, revenue generation, and competitive advantage. The same resources (e.g., customer information) are often used by more than one part of the business.[4]Maintaining the accuracy and consistency of changing resources is a major challenge in business organizing systems.[5]

Many business organizing systems preserve information needed to satisfy externally imposed regulatory or compliance policies and serve largely to avoid possible catastrophic costs from penalties and lawsuits. In all these cases, resources are maintained as one of the means employed to preserve the business as an ongoing enterprise, not as an end in itself.

Unlike libraries, archives, and museums, indefinite preservation is not the central goal of most business organizing systems. These organizing systems mostly manage information needed to carry out day-to-day operations or relatively recent historical information used in decision support and strategic planning. In addition to these internal mandates, businesses have to conform to securities, taxation, and compliance regulations that impose requirements for long-term information preservation.[6]

Of course, libraries, museums, and archives also confront economic issues as they seek to preserve and maintain their collections and themselves as memory institutions.[7] They view their collections as intrinsically valuable in ways that firms generally do not. Because of this, extensive energy goes into preservation, protection, and storage of resources in memory institutions, and it is more rare that resources may be discarded or de-accessioned. Art galleries are an interesting hybrid because they organize and preserve collections that are valuable, but if they do not manage to sell some things, they will not stay in business.

In between these contrasting purposes of preservation and maintenance are the motives in personal collections, which occasionally are created because of the inherent value of the items but more typically because of their value in supporting personal activities. Some people treasure old photos or collectibles that belonged to their parents or grandparents and imagine their own children or grandchildren enjoying them, but many old collections seem to end up as offerings on eBay. In addition, many personal organizing systems are task-oriented, so their contents need not be preserved after the task is completed.[8]

Preservation

At the most basic level, preservation of resources means maintaining them in conditions that protect them from physical damage or deterioration. Libraries, museums, and archives aim for stable temperatures and low humidity. Permanently or temporarily out-of-service aircraft are parked in deserts where dry conditions reduce corrosion. Risk-aware businesses create continuity plans that involve off-site storage of the data and documents needed to stay in business in the event of a natural disaster or other disruption.

When the goal is indefinite preservation, other maintenance issues arise if resources deteriorate or are damaged. How much of an artifact’s worth is locked in with the medium used to express it? How much restoration should be attempted? How much of an artifact’s essence is retained when digitized?

Digitization and Preserving Resources

Preservation is often a key motive for digitization, but digitization alone is not preservation. Digitization creates preservation challenges because technological obsolescence of computer software and hardware require ongoing efforts to ensure the digitized resources can be accessed.

Technological obsolescence is the major challenge in maintaining digital resources. The most visible one is a result of the relentless evolution of the physical media and environments used to store digital information in both institutional or business and personal organizing systems. Computer data began to be stored on magnetic tape and hard disk drives six decades ago, on floppy disks four decades ago, on CDs three decades ago, on DVDs two decades ago, on solid-state drives half a decade ago, and in “cloud-based” or “virtual” storage environments in the last decade. As the capacity of storage technologies grows, economic and efficiency considerations often make the case to adopt new technology to store newly acquired digital resources and raise questions about what to do with the existing ones.[9]

The second challenge might seem paradoxical. Even though digital storage capacity increases at a staggering pace, the expected useful lifetimes of the physical storage media are measured in years or at best in decades. Colloquial terms for this problem are data rot or “bit rot.” In contrast, books printed on acid-free paper can last for centuries. The contrast is striking; books on library shelves do not disappear if no one uses them, but digital data can be lost if no one wants access to it within a year or two after its creation.[10]

However, limits to the physical lifetime of digital storage media are much less significant than the third challenge, the fact that the software and its associated computing environment used to parse and interpret the resource at the time of preservation might no longer be available when the resource needs to be accessed. Twenty-five years ago most digital documents were created using the Word Perfect word processor, but today the vast majority is created using Microsoft Word and few people use Word Perfect today. Software and services that convert documents from old formats to new ones are widely available, but they are only useful if the old file can be read from its legacy storage medium.[11]

Because almost every digital device has storage associated with it, problems posed by multiple storage environments can arise at all scales of organizing systems. Only a few years ago people often struggled with migrating files from their old computer, music player or phone when they got new ones. Web-based email and applications and web-based storage services like Dropbox, Amazon Cloud Drive, and Apple iCloud eliminate some data storage and migration problems by making them someone else’s responsibility, but in doing so introduce privacy and reliability concerns.

It is easy to say that the solutions to the problems of digital preservation are regular recopying of the digital resources onto new storage media and then migrating them to new formats when significantly better ones come along. In practice, however, how libraries, businesses, government agencies or other enterprises deal with these problems depends on their budgets and on their technical sophistication. In addition, not every resource should or can always be migrated, and the co-existence of multiple storage technologies makes an organizing system more complex because different storage formats and devices can be collectively incompatible.

(Interoperability and integration are discussed in Interactions with Resources.)

Preserving the Web

Preservation of web resources is inherently problematic. Unlike libraries, museums, archives, and many other kinds of organizing systems that contain collections of unchanging resources, organizing systems on the web often contain resources that are highly dynamic. Some websites change by adding content, and others change by editing or removing it.[12]

Longitudinal studies have shown that hundreds of millions of web pages change at least once a week, even though most web pages never change or change infrequently.[13] Nevertheless, the continued existence of a particular web page is hardly sufficient to preserve it if it is not popular and relevant enough to show up in the first few pages of search results. Persistent access requires preservation, but preservation is not meaningful if there is no realistic probability of future access.

Comprehensive web search engines like Google and Bing use crawlers to continually update their indexed collections of web pages and their search results link to the current version, so preservation of older versions is explicitly not a goal. Furthermore, search engines do not reveal any details about how frequently they update their collections of indexed pages.[14]

Preserving Resource Instances

A focus on preserving particular resource instances is most clear in museums and archives, where collections typically consist of unique and original items. There are many copies and derivative works of the Mona Lisa, but if the original Mona Lisa were destroyed none of them would be acceptable as a replacement.[16]

Archivists and historians argue that it is essential to preserve original documents because they convey more information than just their textual content. Paul Duguid recounts how a medical historian used faint smells of vinegar in 18th-century letters to investigate a cholera epidemic because disinfecting letters with vinegar was thought to prevent the spread of the disease. Obviously, the vinegar smell would not have been part of a digitized letter.[17]

Zoos often give a distinctive or attractive animal a name and then market it as a special or unique instance. For example, the Berlin Zoo successfully marketed a polar bear named Knut to become a world famous celebrity, and the zoo made millions of dollars a year through increased visits and sales of branded merchandise. Merchandise sales have continued even though Knut died unexpectedly in March 2011, which suggests that the zoo was less interested in preserving that particular polar bear than in preserving the revenue stream based on that resource.[18]

Most business organizing systems, especially those that “run the business” by supporting day-to-day operations, are designed to preserve instances. These include systems for order management, customer relationship management, inventory management, digital asset management, record management, email archiving, and more general-purpose document management. In all of these domains, it is often necessary to retrieve specific information resources to serve customers or to meet compliance or traceability goals.

Recent developments in sensor technology enable very extensive data collection about the state and performance of machines, engines, equipment, and other types of physical resources, including human ones. (Are you wearing an activity tracker right now?) When combined with historical information about maintenance activity, predictive analytics techniques can use this data to determine normal operating ranges and indicators of coming performance degradation or failures. Predictive maintenance can maximize resource lifetimes while minimizing maintenance and inventory costs. These techniques have recently been used to predict when professional basketball players are at risk of an injury, potentially enabling NBA teams to identify the best time to rest their star players without impairing their competitive strategy.[19]

Preserving Resource Types

Some business organizing systems are designed to preserve types or classes of resources rather than resource instances. In particular, systems for content management typically organize a repository of reusable or “source” information resources from which specific “product” resources are then generated. For example, content management systems might contain modular information about a company’s products that are assembled and delivered in sales or product catalogs, installation guides, operating guides, or repair manuals.[20]

Businesses strive to preserve the collective knowledge embodied in the company’s people, systems, management techniques, past decisions, customer relationships, and intellectual property. Much of this knowledge is “know how”—knowing how to get things done or knowing how things work—that is tacit or informal. Knowledge management systems(KMS) are a type of business organizing system whose goal is to capture and systematize these information resources.[21] As with content management, the focus of knowledge management is the reuse of “knowledge as type,” putting the focus on the knowledge rather than the specifics of how it found its way into the organizing system.

Libraries have a similar emphasis on preserving resource types rather than instances. The bulk of most library collections, especially public libraries, is made up of books that have many equivalent copies in other collections. When a library has a copy of Moby Dick it is preserving the abstract work rather than the particular physical instance—unless the copy of Moby Dick is a rare first edition signed by Melville.

Even when zoos give their popular animals individual names, it seems logical that the zoo’s goal is to preserve animal species rather than instances because any particular animal has a finite lifespan and cannot be preserved forever. [22]

Preserving Resource Collections

In some organizing systems any specific resource might be of little interest or importance in its own right but is valuable because of its membership in a collection of essentially identical items. This is the situation in the data warehouses used by businesses to identify trends in customer or transaction data or in the huge data collections created by scientists. These collections are typically analyzed as complete sets. A scientist does not borrow a single data point when she accesses a data collection; she borrows the complete dataset consisting of millions or billions of data points. This requirement raises difficult questions about what additional software or equipment need to be preserved in an organizing system along with the data to ensure that it can be reanalyzed.[23]

Sometimes, specific items in a collection might have some value or interest on their own, but they acquire even greater significance and enhanced meaning because of the context created by other items in the collection that are related in some essential way. The odd collection of “things people swallow that they should not” at the Mütter Museum is a perfect example.[24]

Curation

For almost a century curation has referred to the processes by which a resource in a collection is maintained over time, which may include actions to improve access or to restore or transform its representation or presentation.[25]

Furthermore, especially in cultural heritage collections, curation also includes research to identify, describe, and authenticate resources in a collection. Resource descriptions are often updated to reflect new knowledge or interpretations about the primary resources.[26]

Curation takes place in all organizing systems—at a personal scale when we rearrange a bookshelf to accommodate new books or create new file folders for this year’s health insurance claims, at an institutional scale when a museum designs a new exhibit or a zoo creates a new habitat, and at web scale when people select photos to upload to Flickr or Facebook and then tag or “Like” those uploaded by others.

An individual, company, or any other creator of a website can make decisions and employ technology that maintains the contents, quality and character of the site over time. In that respect website curation and governance practices are little different than those for the organizing systems in memory institutions or business enterprises. The key to curation is having clear policies for collecting resources and maintaining them over time that enable people and automated processes to ensure that resource descriptions or data are authoritative, accurate, complete, consistent, and non-redundant.

Institutional Curation

Curation is most necessary and explicit in institutional organizing systems where the large number of resources or their heterogeneity requires choices to be made about which ones should be most accessible, how they should be organized to ensure this access, and which ones need most to be preserved to ensure continued accessibility over time. Curation might be thought of as an ongoing or deferred selection activity because curation decisions must often be made on an item-by-item basis.

Curation in these institutional contexts requires extensive professional training.The institutional authority empowers individuals or groups to make curation decisions. No one questions whether a museum curator or a compliance manager should be doing what they do.[27]

Institutional curation may be supported by automated methods. An “approval plan” is often implemented for the acquisition of new books by libraries that involves an initial selection of certain criteria (such as “published by an American university press; costs less than $100; not a reissue of an earlier edition; classed within a particular Library of Congress range”) that enable libraries to automatically purchase all books meeting the criteria. While the approval plan can certainly be considered a selection activity, we cite it in maintenance as an example of a strategy to maintain the currency and relevancy of a given collection.

Individual Curation

Curation by individuals has been studied a great deal in the research discipline of Personal Information Management (PIM).[28] Much of this work has been influenced for decades by a seminal article written by Vannevar Bush titled As We May Think. Bush envisioned the Memex, “a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility.” Bush’s most influential idea was his proposal for organizing sets of related resources as “trails” connected by associative links, the ancestor of the hypertext links that define today’s web.[29]

Social and Web Curation

Many individuals spend a great amount of time curating their own websites, but when a site can attract large numbers of users, it often allows users to annotate, “tag,” “like,” “+1,” and otherwise evaluate its resources. The concept of curation has recently been adapted to refer to these volunteer efforts of individuals to create, maintain, and evaluate web resources.[30] The massive scale of these bottom-up and distributed activities is curation by “crowdsourcing,” the continuously aggregated actions and contributions of users.[31]

The informal and organic “folksonomies” that result from their aggregated effort create organization and authority through network effects.[32] This undermines traditional centralized mechanisms of organization and governance and threatens any business model in publishing, education, and entertainment that has relied on top-down control and professional curation.[33]Professional curators are not pleased to have the ad hoc work of untrained people working on websites described as curation.

Most websites are not curated in a systematic way, and the decentralized nature of the web and its easy extensibility means that the web as a whole defies curation. It is easy to find many copies of the same document, image, music file, or video and not easy to determine which is the original, authoritative or authorized version. Broken links return “Error 404 Not Found” messages.[34]

Problems that result from lazy or careless webmastering are minor compared to those that result from deliberate misclassification, falsification, or malice.An entirely new vocabulary has emerged to describe these web resources with bad intent: “spam,” “phishing,” “malware,” “fakeware,” “spyware,” “keyword stuffing,” “spamdexing,” “META tag abuse,” “link farms,” “cybersquatters,” “phantom sites,” and many more.[35] Internet service providers, security software firms, email services, and search engines are engaged in a constant war against these kinds of malicious resources and techniques.[36]

Since we cannot prevent these deceptions by controlling what web resources are created in the first place, we have to defend ourselves from them after the fact. “Defensive curation” techniques include filters and firewalls that block access to particular sites or resource types, but whether this is curation or censorship is often debated, and from the perspective of the government or organization doing the censorship it is certainly curation. Nevertheless, the decentralized nature of the web and its open protocols can sometimes enable these controls to be bypassed.

Computational Curation

Search engines continuously curate the web because the algorithms they use for determining relevance and ranking determine what resources people are likely to access. At a smaller scale, there are many kinds of tools for managing the quality of a website, such as ensuring that HTML content is valid, that links work, and that the site is being crawled completely. Another familiar example is the spam and content filtering that takes place in our email systems that automatically classifies incoming messages and sorts them into appropriate folders.

One might think that computational curation is always more reliable than any curation carried out by people. Certainly, it seems that we should always be able to trust any assertion created by context-aware resources like temperature or location sensors. But can we trust the accuracy of web content? Search engines use the popularity of web pages and the structure of links between them to compute relevance. But popularity and relevance do not always ensure accuracy. We can easily find popular pages that prove the existence of UFOs or claim to validate wacky conspiracy theories.

Computational curation is more predictable than curation done by people, but search engines have long been accused of bias built into their algorithms. For example, Google’s search engine has been criticized for giving too much credibility to websites with .edu domain names, to sites that have been around for a long time, or that are owned by or that partner with the company, like Google Maps or YouTube.[37]

In organizing systems that contain data, there are numerous tools for name matching, the task of determining when two different text strings denote the same person, object, or other named entity. This problem of eliminating duplicates and establishing a controlled or authoritative version of the data item arises in numerous application areas but familiar ones include law-enforcement and counter-terrorism. Done incorrectly, it might mean that you end up on a “watch list” and experience difficulties every time you want to fly commercially.

An extremely promising new approach to computational curation involves using scientific measuring equipment to analyze damaged physical resources and then building software models of the resources that can be manipulated to restore the resources or otherwise improve access to their content. For example, the first sound recordings were made using rotating wax cylinders; sounds caused a diaphragm to vibrate, the pattern of vibration was transferred into a connected stylus, which then cut a groove into the wax. When the cylinder was rotated past a passive stylus, it would vibrate according to the groove pattern, and the amplified vibrations could be heard as the replayed sound. Unfortunately, wax cylinders from the 19th century are now so fragile that they would fall apart if they were played. This dilemma was resolved by Carl Haber, an experimental physicist at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Haber used image processing techniques to convert microscope-detailed scans of the grooves in the wax cylinders. Measurements of the grooves could then be transformed to reproduce the sounds captured in the grooves.[38]

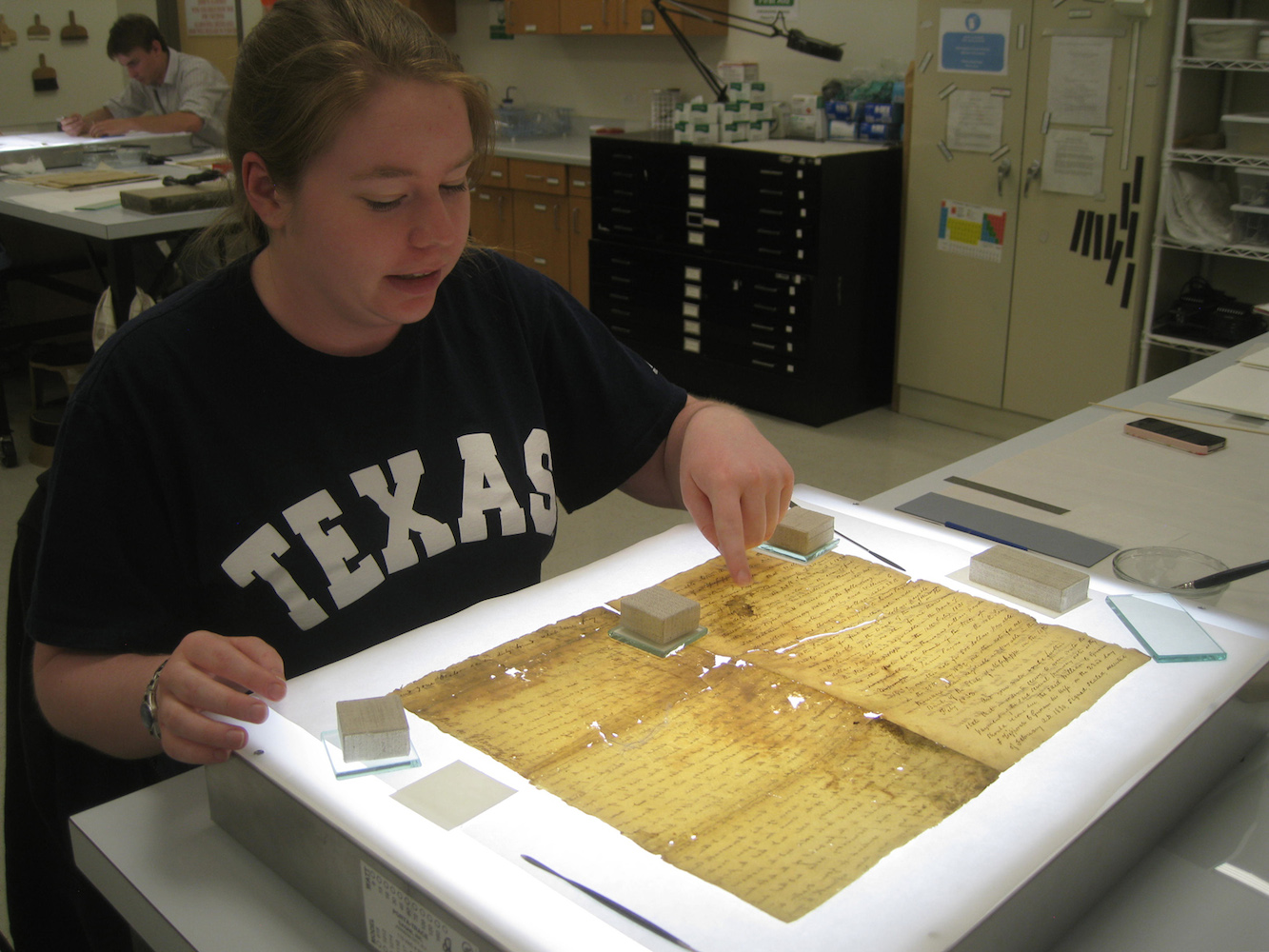

A second example of computational curation applied to digital preservation is work done by a research team led by Melissa Terras and Tim Weyrich at University College London to build a 3-dimensional model of a 17th-century “Great Parchment Book” damaged in an 18th-century fire. The parchment was singed, shriveled, creased, folded, and nearly impossible to read (see website). After traditional document restoration techniques (e.g., illustrated in photos in “Preservation”) went as far as they could, the researchers used digital image capture and modeling techniques to create a software model of the parchment that could stretch and flatten the digital document to discover text hidden by the damage.

Discarding, Removing, and Not Keeping

So far, we have discussed maintenance as activities involved in preserving and protecting resources in an organizing system over time. An essential part of maintenance is the phasing out of resources that are damaged or unusable, expired or past their effectivity dates, or no longer relevant to any interaction.

Many organizations admit to a distinct lack of strategy in the removal aspect of maintenance. A firm with outdated storage technology might have to discard older data simply to make room for new data, and might do so without considering that keeping some summary statistics would be valuable for historical analysis. Other firms might be biased towards keeping information just because they went to the trouble of collecting or acquiring it. Some amount of “intelligent” removal is an essential ingredient in any maintenance regime, and a popular book argues forcefully for continually discarding resources from personal organizing systems as a method of focusing on the resources that really matter. (See the sidebar, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up.)

In memory institutions, common terms for getting rid of resources include discarding, de-accession, de-selection, and weeding.

Efforts by libraries to automate the discarding of books that have not circulated for several years might seem like the obvious counterpart to their automated acquisition, but such efforts often produce passionate complaints from library patrons.[39]

Other domains have other mechanisms and terms for removing resources. Employess are removed by firing, layoff, or retirement . Athletes are cut or waived or sent down from a sports team if their performance deteriorates.

Keeping an organizing system current often involves some amount of elimination of older resources in order to make space for the new: in fashion retail, the floor is constantly restocked with the latest styles. Software development teams will halt active support and documentation efforts of legacy versions.

Information resources are often discarded to comply with laws about retaining sensitive data. Governments and office holders sometimes destroy documents that might prove damaging or embarrassing if they are discovered through Freedom of Information requests or by opposing political parties.

More positively, the “right to be forgotten” movement and intentional destruction of information records about prior bankruptcy, credit problems, or juvenile arrests after a certain period of time has passed can be seen as a policy of “social forgetfulness” that gives people a chance to get on with their lives.[40]

It is worth noting that the ability to discard without having to reuse is relatively recent. Historically, the urge and need to discard has clashed with the availability of resources. In the Middle Ages, liturgical texts or music would be phased out, perhaps when the music had gone out of style or when entire sections of the liturgy were phased out by decree. When this happened, they would reuse the parchment or vellum, either by scraping it down or by flipping it over, pasting it in a book, and using the other side. The former of these solutions often created a palimpsest, a document or other resource in which the remnants of older content remain visible under the new.

Some people have difficulty in discarding things, regardless of their actual value. This behavior is called hoarding, and is now regarded as a kind of obsessive-compulsive disorder that requires treatment because it can cause emotional, physical, social, and even legal problems for the hoarder and family members. It seems unsympathetic that many TV shows and stories have been produced about especially compulsive hoarding. A famous example is that of the Collyer brothers in New York, who shut themselves off from the world for years, and when they were found dead inside their home in 1947 it contained 140 tons of collected items, including 25,000 books, fourteen pianos, thousands of bottles and tin cans, hundreds of yards of fabrics, and even a Model T car chassis.[41]

Governance

Governance overlaps with curation in meaning, but typically has more of policy focus (what should be done), rather than a process focus (how to do it). Governance is also more frequently used to describe curation in business and scientific organizing systems rather than in libraries, archives, and museums. Governance has a broader scope than curation because it extends beyond the resources in a collection and also applies to the software, computing, and networking environments needed to use them. This broader scope also means that governance must specify the rights and responsibilities for the people who might interact with the resources, the circumstances under which that might take place, and the methods they would be allowed to use.

Corporate governance is a common term applied to the ongoing maintenance and management of the relationship between operating practices and long-term strategic goals.[42]

Data governance policies are often shaped by laws, regulations or policies that prohibit the collection of certain kinds of objects or types of information. Privacy laws prohibit the collection or misuse of personally identifiable information about healthcare, education, telecommunications, video rental, and in some countries restrict the information collected during web browsing.[43]

Governance in Business Organizing Systems

Governance is essential to deal with the frequent changes in business organizing systems and the associated activities of data quality management, access control to ensure security and privacy, compliance, deletion, and archiving. For many of these activities, effective governance involves the design and implementation of standard services to ensure that the activities are performed in an effective and consistent manner.[44]

Today’s information-intensive businesses capture and create large amounts of digital data. The concept of “business intelligence” emphasizes the value of data in identifying strategic directions and the tactics to implement them in marketing, customer relationship management, supply chain management and other information-intensive parts of the business.[45] A management aspect of governance in this domain is determining which resources and information will potentially provide economic or competitive advantages and determining which will not. A conceptual and technological aspect of governance is determining how best to organize the useful resources and information in business operations and information systems to secure the potential advantages.

Business intelligence is only as good as the data it is based on, which makes business data governance a critical concern that has rapidly developed its own specialized techniques and vocabulary. The most fundamental governance activity in information-driven businesses is identifying the “master data” about customers, employees, materials, products, suppliers, etc., that is reused by different business functions and is thus central to business operations.[46]

Because digital data can be easily copied, data governance policies might require that all sensitive data be anonymized or encrypted to reduce the risk of privacy breaches. To identify the source of a data breach or to facilitate the assertion of a copyright infringement claim a digital watermark can be embedded in digital resources.[47]

Governance in Scientific Organizing Systems

Scientific data poses special governance problems because of its enormous scale, which dwarfs the datasets managed in most business organizing systems. A scientific data collection might contain tens of millions of files and many petabytes of data. Furthermore, because scientific data is often created using specialized equipment or computers and undergoes complex workflows, it can be necessary to curate the technology and processing context along with data in order to preserve it. An additional barrier to effective scientific data curation is the lack of incentives in scientific culture and publication norms to invest in data retention for reuse by others. [48]

-

(Guenther and Wolfe 2009).

↵

-

This is the historical and dominant conception of the research library, but libraries are now fighting to prove that they are much more than just repositories because many of their users place greater value “on-the-fly access” of current materials. See (Teper 2005) for a sobering analysis of this dilemma.

↵

-

Today the United States National Archives displays the Declaration of Independence,Bill of Rights, and the U.S. Constitution in sealed titanium cases filled with inert argon gas. Unfortunately, for over a century these documents were barely preserved at all; the Declaration hung on the wall at the United States Patent Office in direct sunlight for about 40 years.

↵

-

Customer information drives day-to-day operations, but is also used in decision support and strategic planning.

↵

-

For businesses “in the world,” a “customer” is usually an actual person whose identity was learned in a transaction, but for many web-based businesses and search engines a customer is a computational model extracted from browser access and click logs that is a kind of “theoretical customer” whose actual identity is often unknown. These computational customers are the targets of the computational advertising in search engines.

↵

-

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the United States and similar legislation in other countries require firms to preserve transactional and accounting records and any document that relates to “internal controls,” which arguably includes any information in any format created by any employee (Langevoort 2006). Civil procedure rules that permit discovery of evidence in lawsuits have long required firms to retain documents, and the proliferation of digital document types like email, voice mail, shared calendars and instant messages imposes new storage requirements and challenges (Levy and Casey 2006). However, if a company has a data retention policy that includes the systematic deletion of documents when they are no longer needed, courts have noted that this is not willful destruction of evidence.

↵

-

Libraries are increasingly faced with the choice of providing access to digital resources through renewable licensing agreements, “pay per view” arrangements, or not at all. To some librarians, however, the failure to obtain permanent access rights “offends the traditional ideal of libraries” as memory institution(Carr 2010).

↵

-

For example. students writing a term paper usually organize the printed and digital resources they rely on; the former are probably kept in folders or in piles on the desk, and the latter in a computer file system. This organizing system is not likely to be preserved after the term paper is finished. An exception that proves the rule is the task of paying income taxes for which (in the USA) taxpayers are legally required to keep evidence for up to seven years after filing a tax return (

www.irs.gov/Businesses/Small-Businesses-&-Self-Employed/How-long-should-I-keep-records%3F).↵

-

(Rothenberg 1999).

↵

-

(Pogue 2009).

↵

-

Many of those Word Perfect documents were stored on floppy disks because floppy disk drives were built into almost every personal computer for decades, but it would be hard to find such disk drives today. And even if someone with a collection of word processor documents stored of floppy disks in 1995 had copied those files to newer storage technologies, it is unlikely that the current version of the word processor would be able to read them. Software application vendors usually preserve “backwards compatibility” for a few years with earlier versions to give users time to update their software, but few would support older versions indefinitely because to do so can make it difficult to implement new features.

Digital resources can be encoded using non-proprietary and standardized data formats to ensure “forward compatibility” in any software application that implements the version of the standard. However, if the ebook reader, web browser, or other software used to access the resource has capabilities that rely on later versions of the standards the “old data” will not have taken advantage of them.

↵

-

This is tautologically true for sites that publish news, weather, product catalogs with inventory information, stock prices, and similar continually updated content because many of their pages are automatically revised when events happen or as information arrives from other sources. It is also true for blogs, wikis, Facebook, Flickr, YouTube, Yelp and the great many other “Web 2.0” sites whose content changes as they incorporate a steady stream of user-generated content.

In some cases changes to web pages are attempts to rewrite history and prevent preservation by removing all traces of information that later turned out to be embarrassing, contradictory, or politically incorrect. When pages cannot be changed, like the archives of newspapers published on the web, only the search engine can remove them from search results, and in 2014 the European Court ruled that people could ask Google to do that.

↵

-

(Fetterly et al. 2003).

Most people understand that web pages can change, but most changed web pages do not highlight the changes. A “diff” tool from Microsoft reveals them. http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/...E/default.aspx

↵

-

However, when a website disappears its first page can often be found in the search engine’s index “cache” rather than by following what would be a broken link.

↵

-

Brewster Kahle has been described as a computer engineer, Internet entrepreneur, Internet activist, advocate of universal access to knowledge, and digital librarian (

http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Brewster_Kahle). In addition to websites, the Internet Archive preserves several million books, over a million pieces of video, 400,000 news programs from broadcast TV, over a million audio recordings, and over 100,000 live music concerts.The Memento project has proposed a specification for using (VandeSompel 2010).

↵

-

People might still enjoy the many Mona Lisa parodies and recreations. See

http://www.megamonalisa.com,http://www.oddee.com/item_96790.aspx,http://www.chilloutpoint.com/art_and_design/the-best-mona-lisa-parodies.html.↵

-

(Brown and Duguid 2002).

↵

-

(Savodnik 2011).

↵

-

(Talukder 2016)

↵

-

The set of content modules and their assembly structure for each kind of generated document conforms to a template or pattern that is called the document type model when it is expressed in XML.

↵

-

Company intranets, wikis, and blogs are often used as knowledge management technologies; Lotus Notes and Microsoft SharePoint are popular commercial systems. (See the case study in “Knowledge Management for a Small Consulting Firm”.)

↵

-

In addition, the line between “preserving species” and “preserving marketing brands” is a fine one for zoos with celebrity animals, and in animal theme parks like Sea World, it seems to have been crossed. “Shamu” was the first killer whale (orca) to survive long in captivity and performed for several years at SeaWorld San Diego. Shamu died in 1971 but over forty years later all three US-based SeaWorld parks have Shamu shows and Shamu webcams.

↵

-

(Manyika et al. 2011).

↵

-

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum houses a novel collection of artifacts meant to “educate future doctors about anatomy and human medical anomalies.” No museum in the world is like it; it contains display cases full of human skulls, abnormal fetuses in jars, preserved human bodies, a garden of medicinal herbs, and many other unique collections of resources.

However, one sub-collection best reflects the distinctive and idiosyncratic selection and arrangement of resources in the museum. Chevalier Jackson, a distinguished laryngologist, collected over 2,000 objects extracted from the throats of patients. Because of the peculiar focus and educational focus of this collection, and because there are few shared characteristics of “things people swallow that they should not,” the characteristics and principles used to organize and describe the collection would be of little use in another organizing system. What other collection would include toys, bones, sewing needles, coins, shells, and dental material? It is hard to imagine that any other collection that would include all of these items plus fully annotated record of sex and approximate age of patient, the amount of time the extraction procedure took, the tool used, and whether or not the patient survived.

↵

-

Curation is a very old concept whose Medieval meaning focused on the “preservation and cure of souls” by a pastor, priest, or “curate” (Simpson and Weiner 1989). A set of related and systematized curation practices for some class of resources is often called a curation system, especially when they are embodied in technology.

↵

-

Information about which resources are most often interacted with in scientific or archival collections is essential in understanding resource value and quality.

↵

-

In memory institutions, the most common job titles include “curator” or “conservator.” In for-profit contexts where “governance” is more common than “curation” job titles reflect that difference. In addition to “governance,” job titles often include “recordkeeping,” “compliance,” or “regulatory” prefixes to “officer,” “accountant,” or “analyst” job classifications.

↵

-

Because personal collections are strongly biased by the experiences and goals of the organizer, they are highly idiosyncratic, but still often embody well-thought-out and carefully executed curation activities (Kirsh 2000), (Jones 2007), (Marshall 2007),(Marshall 2008).

↵

-

(Bush 1945). Bush imagined that Memex users could share these packages of trails and that a profession of trailbuilders would emerge. However, he did not envision that the Memexes themselves could be interconnected, nor did he imagine that their contents could be searched computationally.

↵

-

(Howe 2008).

↵

-

The most salient example of this so called “community curation” activity is the work to maintain the Wikipedia open-source encyclopedia according to a curation system of roles and functions that governs how and under what conditions contributors can add, revise, or delete articles; receive notifications of changes to articles; and resolve editing disputes (Lovink and Tkacz 2011). Some museums and scientific data repositories also encourage voluntary curation to analyze and classify specimens or photographs (Wright 2010).

↵

-

(Trant 2009).

↵

-

Some popular “community content” sites like Yelp where people rate local businesses have been criticized for allowing positive rating manipulation. Yelp has also been criticized for allowing negative manipulation of ratings when competitors slam their rivals.

↵

-

The resource might have been put someplace else when the site was reorganized or a new web server was installed. It is no longer the same resource because it will have another URI, even if its content did not change.

↵

-

All of these terms refer to types of web resources or techniques whose purpose is to mislead people into doing things or letting things be done to their computers that will cost them their money, time, privacy, reputation, or worse. We know too well what spam is. Phishing is a type of spam that directs recipients to a fake website designed to look like a legitimate one to trick them into entering account numbers, passwords, or other sensitive personal information. Malware, fakeware, or spyware sites offer tempting downloadable content that installs software designed to steal information from or take control of the visiting computer. Keyword stuffing, spamdexing, and META tag abuse are techniques that try to mislead search engines about the content of a resource by annotating it with false descriptions. Link farms or scraper sites contain little useful or original content and exist solely for the purpose of manipulating search engine rankings to increase advertising revenue. Similarly, cybersquatters register domain names with the hope of profiting from the goodwill of a trademark they do not own.

↵

-

(Brown 2009).

↵

-

(Diaz 2005), (Grimmelmann 2009).

↵

-

See video of Haber explaining how this works, Haber has recently been able to build a version of his scanning and image processing technology for use outside the laboratory that he calls Irene (Image, Reconstruct, Erase Noise, Etc.). (Cowen 2015) and (Wilkinson 2014)

↵

-

For an explanation of automated acquisition see Eva Guggemos, Professional archivist and academic librarian

www.quora.com/How-do-libraries-decide-which-books-to-purchase-and-which-books-to-remove-from-circulation.For a cogent discussion of when and for what reasons weeding must take place in university libraries, see

https://mrlibrarydude.wordpress.com/2014/03/12/why-we-weed-book-deselection-in-academic-libraries/.A typical reaction when libraries discard books is described in (Jackman 2015)

↵

-

(Blanchette and Johnson 2002)

↵

-

(Neziroglu 2014) and (Lidz 2003).

↵

-

Libraries and museums must also deal with long-term strategy, but the lesser visibility of library governance and museum governance might simply reflect the greater concerns about fraud and malfeasance in for-profit business contexts than in non-profit contexts and the greater number of standards or “best practices” for corporate governance. (Kim, Nofsinger, and Mohr 2009).

↵

-

Data governance decisions are also often shaped by the need to conform to information or process model standards, or to standards for IT service management like the Information Technology Infrastructure Library(ITIL). See

www.itil-officialsite.com/.↵

-

In this context, these management and maintenance activities are often described as “IT governance” (Weill and Ross 2004). Data classification is an essential IT governance activity because the confidentiality, competitive value, or currency of information are factors that determine who has access to it, how long it should be preserved, and where it should be stored at different points in its lifecycle.

↵

-

(Turban et al. 2010).

↵

-

This master data must be continually “cleansed” to remove errors or inconsistencies, and “de-duplication” techniques are applied to ensure an authoritative source of data and to prevent the redundant storage of many copies of the same resource. Redundant storage can result in wasted time searching for the most recent or authoritative version, cause problems if an outdated version is used, and increase the risk of important data being lost or stolen. (Loshin 2008).

↵

-

(Cox et al. 2007).

↵

-

Recently imposed requirements by the National Science Foundation(NSF), National Institute of Health(NIH) and other research granting agencies for researchers to submit “data management plans” as part of their proposals should make digital data curation a much more important concern (Borgman 2011). (NSF Data Management Plan Requirements:

http://www.nsf.gov/eng/general/dmp.jsp).↵