1.2: What’s Credible Anymore? Fake News and evaluating the information you encounter during your research

- Page ID

- 98026

Fake News, Information Bubbles, and Filter Bubbles

Whether the agenda is to sway public opinion, to affect the outcome of an election, or simply to make money, the proliferation of fake news creators and distributors has complicated our already complication information environment. Perhaps as bad, “fake news” has become an easy way to dismiss stories and information we don’t like without addressing the actual content of such stories.

When you get your news primarily from one source or from one partisan perspective, you are operating in an information bubble. You encounter stories that confirm your view of the world and avoid stories that challenge those views. Information bubbles have a natural appeal—they provide us with stories and perspectives that reinforce what we already believe about the world.

Information bubbles happen naturally when we seek out news and news sources that align with our world views.

This isn’t limited to politics and current events either. They can happen within professions and within organizations too. Social media can also create information bubbles, as like-minded friends share articles they haven’t verified but that conform to some preeived idea of the world. And once a story has been shared enough times, “fake news” can take on an unearned mantle of authority.

Worse, “filter bubbles” are making it more difficult to step outside of those information bubbles. Social media and search engines use algorithms to rank what appears in your feeds and search results. These algorithms look at your previous engagement with social media posts and search results in order to provide you with content that aligns with your interests. These sorts of tailored experiences online--whatever their virtues--limit our information gathering in ways we can’t anticipate. The algorithms are always changing and usually closely guarded by the companies that create and implement them.

This chapter outlines some strategies that you can use to evaluate particular sources of information and particular articles you may encounter. But this is only part of the solution to separating truth from fiction in the information we encounter. Better information habits are required of us.

Until we apply skepticism and critical thought to the information that aligns with our world views just as we would for information that challenges us, we set ourselves up to be fooled by fake news. Until we expand our information bubbles to include more perspectives and coverage from a more diverse community of scholars and reporters, we limit what we can know and learn about our world.

Evaluating Information

Being able to critically evaluate the information we encounter on the web is a hugely valuable research skill. Why?

Because so much information can be found online, and not everything we read is true. Sometimes information can be narrowly accurate, yet still be so biased, selective, or leading as to make the information essentially useless for research purposes. Some information may have once been accurate, but is now simply be too out-of-date to be useful. Sometimes the authors of an article are not experts on what they are writing about. And sometimes the problem is not the accuracy of the information, it’s the lack of research-quality detail and substance.

Being a critical consumer of information is helpful not only in school, but also in our daily lives. Just as we need the information in our college papers to be based on reliable, quality sources, we also want the health advice, product reviews, and other kinds of information we personally use to be reliable.

Accuracy

How do we really know that a given piece of information is accurate? While there is no single rule that guarantees the correctness of the information in a given article or website, there are ways to increase your confidence that the information is factually correct.

If statistics or quotes are provided in an article or on a web page, does the author provide their source? Can that statistic or quote be verified by a reliable second source? If you encounter a quote, might that quote be overly selective or misleading? And can statistics be correct but still misleading?

They can. Misleading graphs (or distorted graphs) are common online. Truncated graphs, while perfectly appropriate in many cases, are a particularly easy way to deceive.

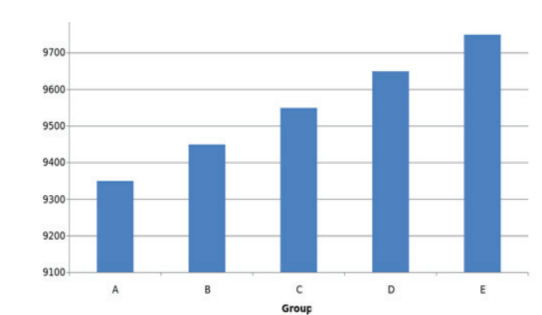

Let’s look at a quick example. The graph below shows rather dramatic change across groups A through E.

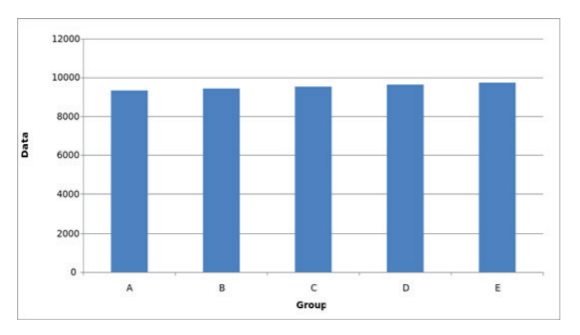

But notice that the Y axis does not begin at 0. Instead it begins with 9,100. If the Y axis did begin with 0, we would see much less dramatic variation across the groups:

Quality information sources will cite their statistical data so that researchers can go to the original source and see the data for themselves.

Quotations can also be taken out of context, as in the example below.

“This would be the best of all possible worlds if there were no religion in it.”

-John Adams

This quote has appeared on many websites and in articles, and it seems clear in meaning. So how could such an unambiguous quote still deceive us? If we look at the full context of the quote, which appeared in a letter Adams once wrote to Thomas Jefferson, it shows a very different meaning:

“Twenty times, in the course of my late reading, have I been on the point of breaking out, ‘this would be the best of all possible worlds, if there were no religion in it!!!!’ But in this exclamation, I should have been as fanatical as Bryant or Cleverly. Without religion, this world would be something not fit to be mentioned in public company--I mean hell.”

-John Adams

Whatever one thinks of Adam’s perspective, his views are clearly misrepresented in the original quote, despite it being taken word-for-word from his own writings.

Authority

When we quote from an author or article in a college-level research paper, we are presuming that the source in some way strengthens the argument we are trying to make, or provides some insight into our research question. But this requires that the sources we use have some kind of authority on our topics. And how to do you know that they do? Why quote or cite an article we’ve discovered on the web and not, say, the opinions of our parents or our friends?

Our educations and life experiences provide each of us with unique expertise, but not all expertise is relevant to a particular research question. A famed political scientist may be an authority on game theory, for example, but that hardly qualifies him or her to conduct heart surgery, or draft technical drawings. The quality of your research very much depends on the authority of your sources, so it is important we learn what we can about the authors we cite and what qualifies them to speak authoritatively on a given topic.

When you evaluate an article or website for use in college-level research, consider these factors:

- What is the author or organization’s credentials?

- Are any credentials even provided? If not, why do they deserve to be cited?

- Is the author qualified to write about this topic?

What is their area of expertise? Is the author affiliated with an educational or research institution?

Objectivity

When we talk about objectivity, we are largely talking about the author’s objectives in producing and publishing the information. Why does the article or website exist? What are the biases of the authors or the organization behind the information? Bias isn’t necessarily bad. Just because an author or organization has a particular point of view does not mean that their information is inaccurate or lacks authority.

The very reason that many groups exist is to advocate for a particular position, and to that end they often collect or generate a lot of high-quality research. That said, you will want to be aware of the objectives of the authors or groups.

And in order to write a well-rounded paper, you will likely want to collect information from authoritative groups with different perspectives as well. When all your information comes from just one side of a debate, your paper will lack balance and perspective.

Do note that all perspectives are not equally informed by relevant expertise. If you are presenting multiple perspectives in a paper, be sure that all those perspectives are informed by authoritative sources.

When considering objectivity, also pay close attention to advertising that appears on a website. The purpose of some websites is to sell a particular product, not necessarily to educate. While they may host articles as well, the articles are basically just ads for the product. Even more insidious, companies may run elaborate advertisements on legitimate websites that are meant to look and read like normal articles, but are in fact just promotional materials. “Sponsored content” on legitimate news websites is increasingly common.

These articles may be written by industry lobbyists or political partisans and can appear alongside legitimate news stories.

Often all that distinguishes “sponsored content” from real news is a small, easily overlooked label. Do not be fooled.

Ask yourself…

- Is the information fact, opinion, or propaganda?

- Is the information well-researched? Is there a bibliography or citations or references at the end?

- Is the author objective and un-biased? Bias isn’t always disqualifying, but you will always want to be aware of what the author’s bias is.

Currency

Some of your research projects may require very up-to-date information. For example, if you are researching present-day population statistics, you won’t want to use the 1980 census figures. If you are writing about public sentiment on a hot-button social issue, old data is worse than useless--it may be downright deceptive. When we talk about currency, we’re talking about how current the information is in a book or article. For some projects and discipines older information might be fine. But for many research topics, currency is a major consideration.

Sometimes the only information available is a bit more aged than is ideal. In those cases we make a judgement call about whether to use it in our work. Often though, we can track down more recent statistics with a little detective work. For example, what is the source of the information?

The US government is one popular source for statistical information. If the government statistics you encounter in an article are dated, perhaps newer statistics have been released since the article was published. Going to the information’s source is good first step.

Ask yourself:

- When was the information published or produced? Will dated information still be relevant to my research project?

- With web-based articles, how many dead links appear on the site? Does the site still receive regular updates appropriate to the content?

Coverage

Earlier when we talked about objectivity, we also talked about bias. While bias is not inherently bad, you would not want your total pool of resources to reflect the same bias.

Otherwise you are only getting part of the picture. In part, this is what “coverage” asks: what part of the picture are you getting with your information resource?

Is the material presented at an appropriate level? An article may contain correct information, but may lack the sort of depth of content necessary for research purposes.

Does the resource add new information or does it simply compile information easily found elsewhere? If the work merely compiles the work of others, would those original sources be more appropriate for use in your work?

When considering accuracy, authority, objectivity, currency, and coverage, there are often no clear-cut answers.

An article that may be appropriate for one kind of research question may not be appropriate for another. Make delib-erate, informed judgements, as the quality of your sources will greatly impact the overall quality of your work.