22.8: Obedience

- Page ID

- 95232

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

The Milgram Experiments

Obedience to authority is a kind of compliance. It occurs when someone can punish us for disobeying, but it also occurs when the person making the request seems to have a legitimate right to do so. The notions of conformity, compliance, and obedience shade off into each other, and we won’t be concerned with drawing precise boundaries among them. The important point is that there are many clear cases of each, and in all of them the actions of others can influence us. We are trained to obey. But not all obedience involves a blind, cringing willingness to do whatever we are told; there are often good reasons for obeying. It would be impossible to raise children if they never did what they were told. And in many cases, there are good reasons for adults to comply with the directives of legitimate authorities. If a police officer directs our car down another street, it is usually reasonable to do as they ask.

But sometimes people fulfill requests or follow orders that harm others, or that violate their own views about right and wrong. Excessive deference to authority occurs when people give in too much to authority and quit thinking for themselves. This is what happened in one of the most famous experiments ever conducted.

These experiments were conducted by the psychologist Stanley Milgram and his coworkers at Yale University from 1960 to 1963. In each session, two people entered the waiting room of a psychology laboratory. One was a subject. The second person also said that they were a subject, but they were really a confederate (an accomplice who works with the experimenter).

The experimenter would tell the pair that they are going to participate in an experiment on learning. One of them would play the role of the teacher and the other would play the role of the learner. The two were asked to draw straws to determine who would get which role, but in fact the drawing was rigged so that the real subject was always the teacher and the confederate was always the learner. The learners were supposed to learn certain word pairs (e.g., boy-sky, fat-neck), which they were then expected to repeat in an oral test given by the teacher. The teacher was asked to administer an electric shock to the learner every time the learner made a wrong response (with no response in a brief period counted as a wrong response). The voltage of the shock increased each time in intervals of 15 volts, with the shocks ranging from 15 volts to 450 volts. The shock generator has labels over the various switches ranging from “Slight Shock” up to “Extreme Intensity Shock,” “Danger: Severe Shock,” and “XXX” (Figure 22.8.1). The learners were strapped down so that they could not get up or move so as to avoid the shocks. They were at the mercy of the teacher.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=637&height=134)

The teacher and learner were put in different rooms so that they could not see one another, and they communicated over an intercom. After the first few shocks (at 150 volts), the learner protested and cried out in pain. After a few more shocks, the learner protested that they had a weak heart. And eventually the learner quit responding entirely. But since no response is counted as a wrong response, the subject is expected to continue administering the shocks.

The teachers typically showed signs of nervousness, but when they were on the verge of quitting the experimenter ordered them to continue. The experimenter in fact had a fixed set of responses; they began with the first, then continued down the list until the subject was induced to continue. The list is:

- Please continue (or please go on).

- The experiment requires that you continue.

- It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- You have no other choice, you must go on.

If the subject still refused after getting all four responses, they were excused from the rest of the teaching phase of the experiment.

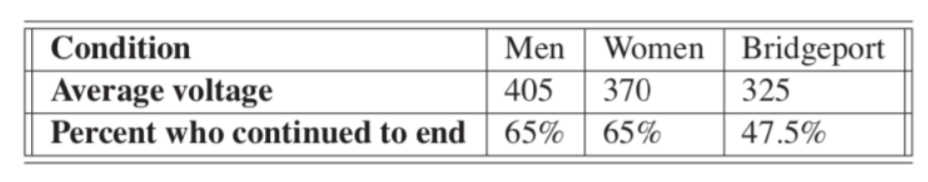

How many people do you think would continue giving shocks all the way up to 450 volts? The experimental setup was described to many people, including students, laypeople, psychologists, and psychiatrists. All of them thought that most of the subjects would defy the experimenter and abandon the experiment when the learner first asked to be released (at 150 volts). The experts predicted that fewer than 4 percent would go to 300 volts, and that only one in a thousand would go all the way to 450 volts. Indeed, Milgram himself thought that relatively few people would go very far. But the results were very different. In this condition of the experiment, 65% of the people went all the way, administering shocks of 450 volts, and all of them went to at least 300 volts before breaking off. (Figure 22.8.2).

Milgram and his colleagues varied the conditions of the experiment, but in all cases, they found much higher rates of obedience than anyone would ever have predicted. For example, nearly as many female subjects continued to the end, where they administered 450-volt shocks to the subject. And when the experiment was conducted in a seedy room in downtown Bridgeport, Connecticut, instead of the prestigious environment of Yale University, obedience was nearly as great.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=614&height=120)

The more directly involved the subject was with the victim, the less the compliance. And, in a result that fits nicely with Ash’s data, if several subjects were involved and one refused to obey, the others found it easier to refuse. On the other hand, many people went along with an authority, even though they didn’t understand what was going on. In short, many of Milgram’s subjects went all the way, delivering what they thought was a very painful shock to someone who seemed to be in great discomfort and to be suffering from heart trouble. A compilation of the results of several studies is given in Figure 22.8.2; the number of subjects in each condition is 40.

In another condition, a team of people (all but one of whom were confederates) had to work together to administer the shocks. One read the word pairs, another pulled the switch, and so on. In this condition if one of the confederates defied the experimenter and refused to continue, only ten percent of the subjects went all the way to 450 volts. As in the Ash studies, one dissenter—one person who refused to go along—made it much easier for other people to refuse as well.

Ethical standards no longer allow studies like Milgram’s, but in the years after his work, over a hundred other studies on obedience were run. They were conducted in various countries and involved numerous variations. Most of them supported Milgram’s results. In an even more real-life context, a doctor called a hospital and asked that an obviously incorrect prescription be administered to a patient. Although ten out of twelve nurses said they wouldn’t dispense such a prescription, twenty-one of the twenty-two nurses that were called did comply.

Changing Behavior vs. Changing Beliefs

In some cases, we do things that we don’t think we should to win the approval of others. For example, many of the subjects in Ash’s conformity studies knew that they were giving a wrong answer, and only did so because of the social pressure they felt. But in many cases, we can only get someone to behave in a certain way (e.g., to shock unwilling victims) if we change the way they think.